Abstract

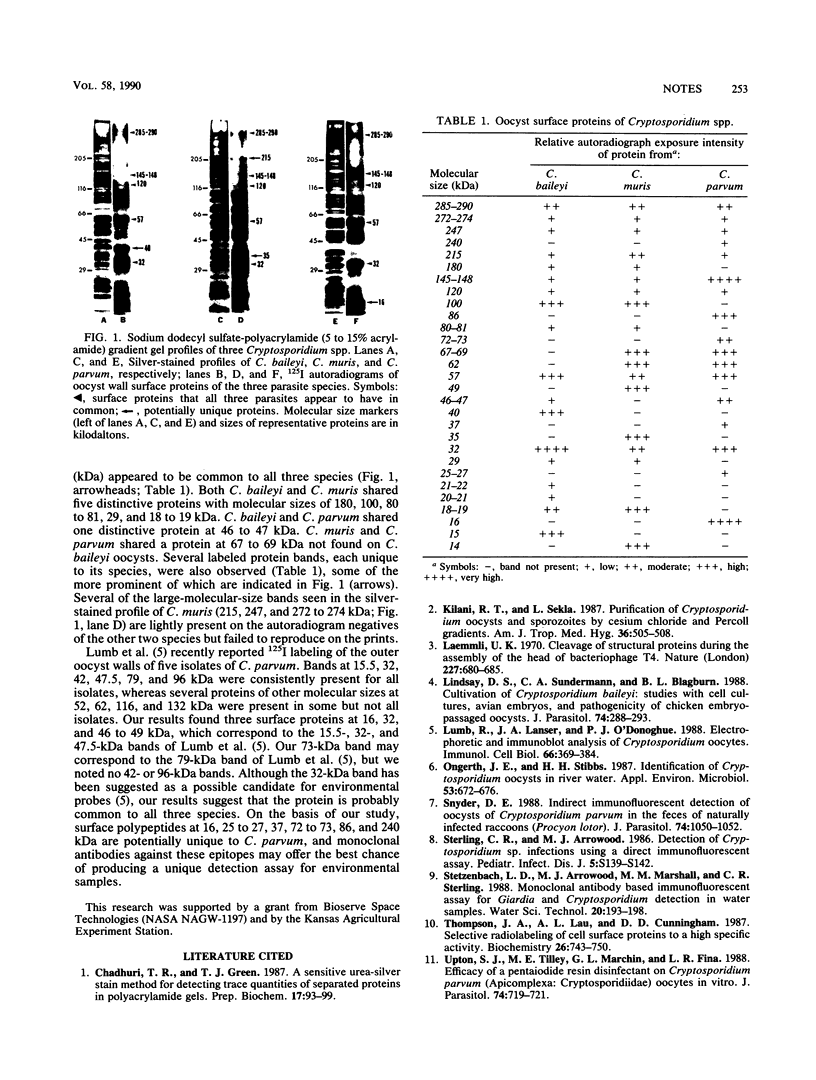

Autoradiography of oocyst wall surface proteins of three Cryptosporidium spp. revealed common bands at 285 to 290, 145 to 148, 120, 57, and 32 kilodaltons (kDa). Cryptosporidium baileyi and C. muris share proteins at 180, 100, 80 to 81, 29, and 18 to 19 kDa; C. baileyi and C. parvum share one protein at 46 to 47 kDa; and C. muris and C. parvum share a protein at 67 to 69 kDa. Additional protein bands, each unique to one species, were also observed.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chaudhuri T. R., Green T. J. A sensitive urea-silver stain method for detecting trace quantities of separated proteins in polyacrylamide gels. Prep Biochem. 1987;17(1):93–99. doi: 10.1080/00327488708062478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilani R. T., Sekla L. Purification of Cryptosporidium oocysts and sporozoites by cesium chloride and Percoll gradients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987 May;36(3):505–508. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.36.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay D. S., Sundermann C. A., Blagburn B. L. Cultivation of Cryptosporidium baileyi: studies with cell cultures, avian embryos, and pathogenicity of chicken embryo-passaged oocysts. J Parasitol. 1988 Apr;74(2):288–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumb R., Lanser J. A., O'Donoghue P. J. Electrophoretic and immunoblot analysis of Cryptosporidium oocysts. Immunol Cell Biol. 1988 Oct-Dec;66(Pt 5-6):369–376. doi: 10.1038/icb.1988.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongerth J. E., Stibbs H. H. Identification of Cryptosporidium oocysts in river water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987 Apr;53(4):672–676. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.4.672-676.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder D. E. Indirect immunofluorescent detection of oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvum in the feces of naturally infected raccoons (Procyon lotor). J Parasitol. 1988 Dec;74(6):1050–1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling C. R., Arrowood M. J. Detection of Cryptosporidium sp. infections using a direct immunofluorescent assay. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1986 Jan-Feb;5(1 Suppl):S139–S142. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198601001-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. A., Lau A. L., Cunningham D. D. Selective radiolabeling of cell surface proteins to a high specific activity. Biochemistry. 1987 Feb 10;26(3):743–750. doi: 10.1021/bi00377a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton S. J., Tilley M. E., Marchin G. L., Fina L. R. Efficacy of a pentaiodide resin disinfectant on Cryptosporidium parvum (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) oocysts in vitro. J Parasitol. 1988 Aug;74(4):719–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]