Abstract

Background

The adjunctive use of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitors with scaling and root planing (SRP) promotes new attachment in patients with periodontal disease. This pilot study was designed to examine aspects of the biological response brought about by the MMP inhibitor low dose doxycycline (LDD) combined with access flap surgery (AFS) on the modulation of periodontal wound repair in patients with severe chronic periodontitis.

Methods

Twenty-four subjects were enrolled into a 12-month, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-masked trial to evaluate clinical, biochemical, and microbial measures of disease in response to 6 months therapy of either placebo capsules + AFS or LDD (20 mg b.i.d.) + AFS. Clinical measures including probing depth (PD), clinical attachment levels (CAL), and bleeding on probing (BOP) as well as gingival crevicular fluid bone marker assessment (ICTP) and microbial DNA analysis (levels and proportions of 40 bacterial species) were performed at baseline and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months.

Results

Patients treated with LDD + AFS showed more potent reductions in PD in surgically treated sites of >6 mm (P <0.05, 12 months). Furthermore, LDD + AFS resulted in greater reductions in ICTP levels compared to placebo + AFS. Rebounds in ICTP levels were noted when the drug was withdrawn. No statistical differences between the groups in mean counts were found for any pathogen tested.

Conclusions

This pilot study suggests that LDD in combination with AFS may improve the response of surgical therapy in reducing probing depth in severe chronic periodontal disease. LDD administration also tends to reduce local periodontal bone resorption during drug administration. The use of LDD did not appear to contribute to any significant shifts in the microbiota beyond that of surgery alone.

Keywords: Bone resorption/prevention and control, doxycycline/therapeutic use, periodontal attachment, periodontal diseases/therapy, surgical flaps

Although periodontitis is initiated by subgingival microbiota, it is generally accepted that mediators of connective tissue breakdown are generated to a large extent by the host’s response to the pathogenic infection.1 In a susceptible host, microbial virulence factors trigger the release of host-derived enzymes such as proteases (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases [MMPs]) which can lead to periodontal tissue destruction.2–4 Collagenases, a subclass of the MMP family, are a group of enzymes capable of disrupting the triple helix of type I collagen in physiological conditions, the primary structural component of the periodontium. Elevated levels of collagenases and other host-derived proteinases (e.g., cathepsins, elastase, tryptases/trypsin like proteinases) have been detected in inflamed gingiva, gingival crevicular fluid (GCF), and saliva of humans with periodontal disease.5–7

Studies have shown that tetracyclines (including the semi-synthetic analogues minocycline and doxycycline) are capable of inhibiting mammalian collagenase activity.8,9 Tetracycline’s inhibitory effect on collagenases appears to occur through the drug’s ability to bind to zinc cations as well as calcium ions in the catalytic domain of the MMP molecule.10,11 In fact, tetracycline also inhibits another class of Ca++ dependent metalloproteinases termed gelatinases (or type IV collagenases)12 and prevents the degradation of a serum protein called α1-proteinase inhibitor (or α1-antitrypsin).13 Furthermore, administration of low doses of doxycycline (LDD; a tetracycline analog) given 20 mg b.i.d. rather than the 50 or 100 mg capsules, typically administered as commercially available antibiotics, effectively inhibit collagenase activity in the gingival tissues as well as in GCF14 without exerting direct effects on the subgingival microorganisms.

Investigations have demonstrated the efficacy of LDD therapy on promoting probing depth (PD) reduction and clinical attachment level (CAL) gains when combined with scaling and root planing (SRP) therapy in chronic periodontitis patients.15,16 Caton and coworkers, in a multi-center clinical trial, found that a 9-month regimen of LDD + SRP provided statistically significant improvements in CAL, PD, and bleeding on probing (BOP) over a 9-month period compared to placebo + SRP in periodontitis patients.17

Many of the crucial cellular responses of early post-surgical wound healing, such as inflammatory infiltration, angiogenesis, and reepithelialization, are made possible through the action of MMPs.18 In addition, the amount and organization of normal wound extracellular matrix are determined by a dynamic balance among overall matrix synthesis, deposition, and degradation.19,20 Expression of MMPs such as collagenases and gelatinases are elevated in acute wounds and still greater levels are found in chronic wounds, indicating that uncontrolled proteolysis is a characteristic of retarded healing.18,21,22 Porcine skin wound models have demonstrated that collagenase has early peak expression at 1 to 7 days post-wounding, followed by slow reduction postoperatively with time, with the sharpest decline occurring after completion of epithelialization.23 The importance of collagen turnover kinetics mediated by MMP expression during wound healing can be demonstrated in diabetes. It has been shown in both preclinical and human studies that uncontrolled hyperglycemia may impair wound healing, and this impairment seems to be directly associated with overexpression of MMPs in the wound site.21,24,25 Furthermore, the utilization of CMT-1 (a chemically modified tetracycline that lacks antimicrobial properties but retains divalent cation binding and MMP inhibitory activity) inhibits diabetic connective tissue breakdown in streptozotocin-induced (STZ) diabetic rats by increasing both steady-state levels of type I procollagen mRNA and collagen synthesis through mechanism(s) that are independent of the antibacterial properties of tetracyclines.26 In another preclinical study,27 STZ-induced diabetic rats exhibited cessation of periosteal and cancellous bone formation. Interestingly, treatment of diabetic animals with 20 mg/day of minocycline (a semisynthetic tetracycline) showed increased bone formation rates comparable to control animals.27 Moreover, growth plate thickness, reduced 43% in diabetic rats, were preserved in the diabetic animals treated with minocycline.27 Therefore, inhibition of elevated levels of specific MMPs during the early phases of tissue repair may contribute to improved treatment outcomes by promoting a favorable wound healing in both connective tissue and bone.

The emphasis of this pilot, placebo-controlled, double-masked clinical investigation was to examine clinical and laboratory measures of periodontal status resulting from a 6-month regimen of LDD on postsurgical periodontal healing in patients with severe chronic periodontitis. Clinical, microbiological, and biochemical parameters were monitored over a 12-month period to determine the biological response of LDD on surgical periodontal therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

A written informed consent was provided for individuals willing to participate in this trial who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in a protocol approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. Twenty-four subjects (aged 30 to 75 years) diagnosed with severe chronic periodontitis were enrolled into a pilot, double-masked, randomized, placebo-controlled, prospective, parallel arm trial. Pertinent inclusion criteria included patients with at least three teeth in the same sextant demonstrating both PD and CAL ≥5 mm to ≤12 mm and BOP. The patients also had to have at least 10 teeth in the functional dentition. Exclusion criteria included chronic treatment (i.e., 2 weeks or more) with any medication known to affect periodontal status (i.e., antibiotics or non-steroidal, anti-inflammatory drugs); antibiotic treatment within 90 days of baseline; clinically significant or unstable organic diseases; compromised healing potential such as connective tissue disorders or bone metabolic diseases; conditions necessitating antibiotic prophylaxis; females who were pregnant (as determined by positive urine pregnancy test at the prescreening visit) or lactating, or who were of child-bearing potential and not utilizing birth control or abstinence; documented allergies to tetracyclines; heavy cigarette smokers (≥2 packs/day); active infectious diseases; immunocompromised; or taking steroid medications. All dental care related to this trial was provided at no cost to eligible participants.

Study Design

Patients eligible to participate in the study received full-mouth SRP within 90 days of baseline (surgery). Fourteen days prior to surgery, subjects were again examined (screening visit) and inclusion/exclusion criteria reviewed. In this visit, two prescreened patients did not meet the inclusion criteria due to healing from SRP. Subjects who still qualified for the study and required access flap surgery (AFS) in a minimum of one sextant were randomized to receive either doxycycline hyclate 20 mg b.i.d.§ or placebo capsules b.i.d. for the 6-month treatment period. Full-mouth manual clinical measurements were recorded for all teeth within 2 weeks of the baseline appointment. Six sites were measured around each tooth in the mouth (mesio-buccal, buccal, distobuccal, disto-lingual, lingual, and mesio-lingual) for PD, CAL, and BOP. At the same visit, microbiological parameters and gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) samples were collected on teeth assigned to receive surgery. Examiners (JLB and MGL) were trained and calibrated to minimize intra-rater (i.e., intraexaminer) variability. In addition, in order to minimize the impact of inter-rater variability on the sensitivity of this study, the same examiner assessed the same patients for the duration of the trial.

Surgical procedures were then performed at baseline (BL) within 14 days of the screening visit by one surgeon (RG). Patients returned for follow-up examinations at months 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 following baseline. Full-mouth manual probing measurements, GCF, ICTP levels, and microbiological samples were assessed at BL and months 3, 6, 9, and 12. Patients received periodontal maintenance therapy at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months following randomization and periodontal surgery. The study design is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Trial Longitudinal Measures

| Month

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Pre-Screening | Screening | Baseline | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 |

| Medical history | X | ||||||||

| Informed consent | X | ||||||||

| SRP | X | ||||||||

| Full-mouth measurements | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Microbial sampling | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Urine pregnancy test | X | X | |||||||

| Surgery | X | ||||||||

| C-telopeptide level | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Maintenance therapy | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Dispense medication | X | X | |||||||

| Drug accountability | X | X | |||||||

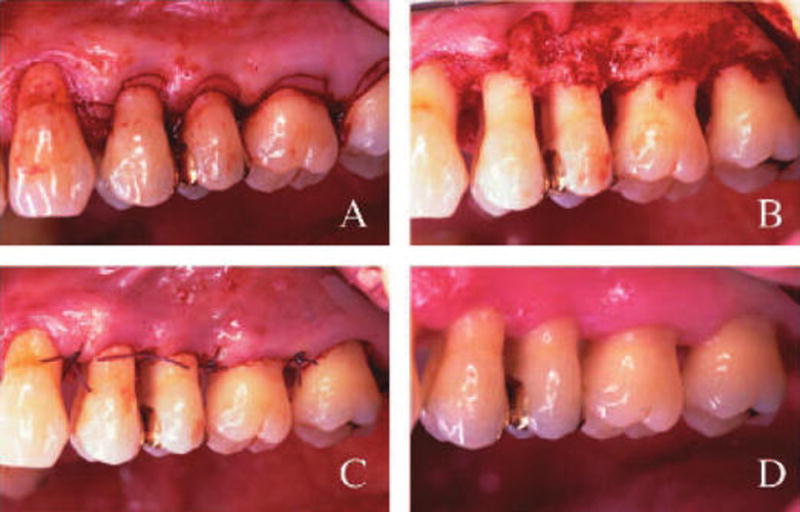

Surgical Procedure

Briefly, following local anesthesia, treatment sextants received AFS, which consisted of submarginal primary incisions (Fig. 1A) and full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap reflection. The tooth root surfaces were debrided, scaled and root planed using hand and sonic instrumentation. Osseous recontouring (osteoplasty) when indicated was performed for flap adaptation (Fig. 1B). The tissues were repositioned with polyglactin 910|| or silk suture materials (Fig. 1C). The surgical sites were then covered with a periodontal dressing. After surgery, patients received pain control medication (an acetaminophen-containing analgesic) when needed and chemical plaque control (0.12% chlorhexidine rinse) for 14 days.

Figure 1.

Access flap surgical procedure in a patient administered 20 mg b.i.d. LDD for a period of 6 months, followed for an additional 6 months. A) Scalloping incisions made to remove the collar of gingival tissue. B) After flap reflection, the surgical site was debrided followed by SRP and osteoplasty where necessary. C) Flaps were repositioned utilizing interrupted sutures 4-0 polyglactin 910. Periodontal dressing was placed and 0.12% chlorhexidine rinses utilized for 14 days. D) LDD-treated sextant 1 year post-LDD therapy + surgery. Note clinical appearance of normal gingival architecture and healing.

Dispensing of Study Medication/Assessment of Compliance

At the screening visit, qualifying patients were assigned a code and were then randomized by a computer software program to the drug or placebo group. At the baseline visit, each patient was issued a 3-month supply of coded study medication including one container for morning and another for afternoon/evening intake. Three months following surgery, subjects returned residual capsules and received an additional 3-month supply. The residual capsules were counted and retained at 3 and 6 months after baseline. Patient compliance (as a percentage) with the dosing schedule was recorded.

Microbiological Monitoring

Subgingival plaque samples were collected from the mesio-buccal sites of each tooth scheduled for surgery using sterile curets. Samples were then placed in sterile, labeled tubes containing 150 μL TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 ml EDTA, pH 7.6) and vortexed. Microbial analyses were performed for the presence and levels of 40 subgingival pathogens (Table 2) utilizing whole genomic DNA probes and checkerboard DNA-DNA hybridization as previously described.28 Signals were recorded as 0: not detected; 1: <105 cells; 2: ~105 cells; 3: 105 to 106 cells; 4: ~106 cells; and 5: >106 cells.

Table 2.

DNA Probes Used to Examine Subgingival Plaque Samples

| Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans | Gemella morbillorum |

| Actinomyces. gerencseriae | Leptotrichia buccalis |

| Actinomyces israelii | Neisseria mucosa |

| Actinomyces naeslundii 1 | Propionibacterium acne |

| Actinomyces naeslundii 2 | Prevotella melaninogenica |

| Actinomyces odontolyticus | Peptostreptococcus micros |

| Tannerella forsythus | Porphyromonas gingivalis |

| Camphylobacter gracilis | Prevotella intermedia |

| Camphylobacter rectus | Prevotella nigrescens |

| Camphylobacter showae | Selemonas noxia |

| Capnocytophaga gingivalis | Streptococcus anginosus |

| Capnocytophaga ochracea | Streptococcus constellatus |

| Capnocytophaga sputigena | Streptococcus gordonii |

| Eikenella corrodens | Streptococcus intermedius |

| Eubacterium nodatum | Streptococcus mitis |

| Eubacterium saburreum | Streptococcus oralis |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum ss nucleatum | Streptococcus sanguis |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum ss polymorphum | Treponema denticola |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum ss vincentii | Treponema socranskii |

| Fusobacterium periodonticum | Veillonella parvula |

Bone Marker (ICTP) Analysis

Gingival crevicular fluid was collected prior to clinical measurements. Gingival tissue surrounding the site to be sampled was dried with gauze, and supragingival plaque was removed. A sterile methylcellulose strip¶ was gently placed into the mesio-buccal aspect of each tooth sulcus or pocket until slight resistance was felt and the GCF collected for 10 seconds. Following collection, the sample was kept on ice for transport to the laboratory and stored at −80°C. The frozen samples were then thawed at room temperature and proteins were eluted through five centrifugations at 3,000 RPM for 5 minutes with 20 μl phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) containing 15 nM aprotinin, 1 mM PMSF, and 0.1% human serum albumin as previously described.29 GCF ICTP levels were quantified using radioimmunoassay.#

Gingival Biopsies (Protease Determination)

Six patients (3 from test group, 3 from placebo group) scheduled to receive two sextants of surgery were evaluated for changes in gingival proteinase activity, utilizing gelatin zymography. Excised tissues from each treatment sextant were immediately placed on ice and subsequently frozen (−80°C). Two months later, tissue samples were harvested from another sextant, during a subsequent surgery. To prepare tissue extracts, samples were thawed on ice, homogenized in PBS, and centrifuged (10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C). Protein concentration in the extracts was determined using a protein assay kit** using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard. The supernatants were diluted with an equal volume of glycerol and stored at −80°C. Protease activity was assessed by 12% gelatin zymography†† as previously described.30

Statistical Analyses

Data available for each patient were subjected to an intent-to-treat analysis and included full-mouth clinical measurements for three different parameters (PD, CAL, and BOP) examined at six sites per tooth. Sample size determination for this pilot study was determined from Golub et al.8 using 80% power for differences expected in a primary biological outcome measure, the bone resorption marker, ICTP. The level and prevalence of 40 species and ICTP levels (pg/site) was measured from the surgically-treated quadrant excluding third molars. Clinical, microbial, and ICTP data were averaged within a patient and then compared between groups. In other analyses, data were stratified according to baseline PD of 1 to 4, 5 to 6, and ≥7 mm and averaged in a patient and then across the study population for clinical parameters and ICTP levels. Differences between drug and placebo groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. Differences with a P value less than 0.05 were considered significant. Microbiologic data were analyzed separately for sites receiving AFS + LDD and AFS + placebo. Mean levels (counts × 105) for each of 40 species were computed for each patient in each treatment category at each visit. Significant differences over time were determined separately for each treatment category using the Quade test and the differences between groups were determined by the Mann-Whitney test. All analyses were performed using the patient as the unit of analysis.

RESULTS

Calibration

The results for calibration of the examiners revealed the intraclass correlation coefficients for PD were >0.90 and for CAL measurements were >0.85. Intraexaminer reliability was determined utilizing the percent agreement within 1 mm between 2 passes and a weighted kappa statistic. The percent agreement within 1 mm was ≥95.5% and ≥90% for PD and CAL measurements, respectively. The weighted kappa statistic was ≥0.92 and ≥0.88 for PD and CAL measurements, respectively.

Demographics

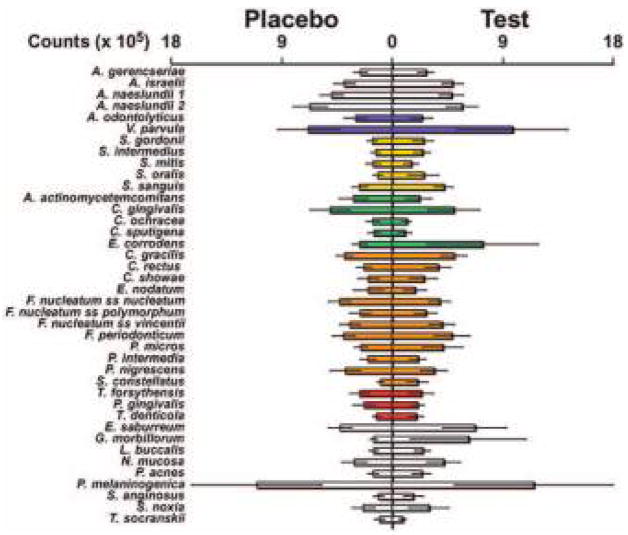

A total of 24 patients entered into the study; 12 were randomized to the LDD + AFS group and 12 to the placebo + AFS group. Ten out of 12 patients in the drug group and 11 out of 12 in the placebo group completed the study for an overall drop-out rate of 12.5%. One patient in the LDD group moved away while the other began administration of a calcium channel blocker that conflicted with the inclusion criteria. The patient in the placebo group reported lethargy after capsule intake and requested exit from the study. At baseline, there were no statistically significant differences (NS) between groups regarding age and gender (Table 3). There were two screening failures at baseline due to changes in PD following SRP making the individuals ineligible for surgical therapy. Seventy-five percent of subjects reported past and current use of tobacco in both LDD and placebo groups (Table 3). In addition, no significant differences were noted between the treatment groups with respect to baseline clinical parameters (PD, BOP, and CAL) and ICTP levels (Table 3). Levels and distribution of subgingival species averaged per group at baseline are displayed in Figure 2. There were no significant differences between LDD and placebo groups for any of the 40 microorganisms analyzed at baseline.

Table 3.

Baseline Mean (± SD) Clinical Characteristics and ICTP

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 12) | Drug (n = 12) | P (Mann-Whitney) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 53.3 (±9.8) | 45.9 (±8.3) | NS* |

| Range | 38–71 | 32–60 | |

| % males | 67% | 67% | NS |

| Tobacco use (n [%]) | |||

| Current | 3 (25%) | 5 (41.7%) | |

| Past | 6 (50%) | 4 (33.3%) | |

| Never | 3 (25%) | 3 (25%) | |

| BOP (%) | 51.3 (±19.3) | 56.6 (±15.9) | NS |

| PD (mm) | 3.0 (±0.5) | 3.1 (±0.3) | NS |

| CAL (mm) | 3.8 (±0.8) | 4.1(±0.8) | NS |

| ICTP (pg/site) | 34.0 (±44.5) | 52.0 (±54.2) | NS |

Not significant.

Figure 2.

Mean counts (±SEM) of species sampled at baseline. Microbial analyses were performed at baseline for the presence and levels of 40 subgingival species utilizing whole genomic DNA probes and checkerboard DNA-DNA hybridization. The mean count for each species was computed for each patient and then averaged across patients. Significant differences were determined using the Mann-Whitney test. SEM = standard error of the means. Colors represent bacteria cluster groupings described by Socransky et al. 31

Compliance

The mean overall drug compliance for the LDD group was 80.6% (range 62% to 105%) while the placebo group mean was 83.0% (range 18% to 100%); difference non-significant (NS) between groups. Data also demonstrated that >90% of patients from both groups were >70% compliant during the study. Patients had a tendency to be slightly more compliant in the morning than in the evening (84.1 ± 6.4% versus 79.4 ± 3.5%, respectively; P >0.05). The subjects also showed trends of better compliance during the first 3 months of the trial compared to the second 3 months (84.8 ± 5.0% versus 79 ± 4.3%, respectively; P >0.05). One patient in the drug group showed low compliance (18%).

Treatment Outcomes: Responses in Clinical Parameters and ICTP Levels

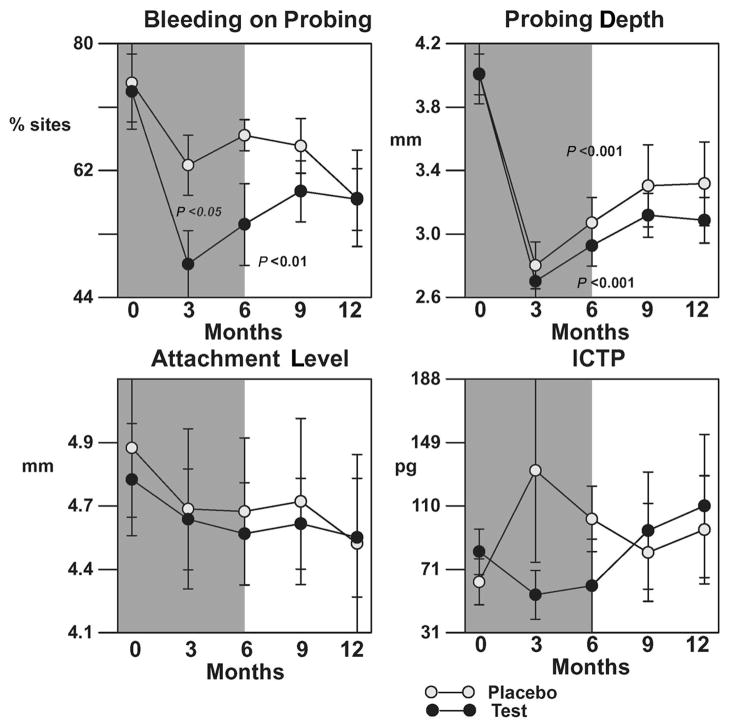

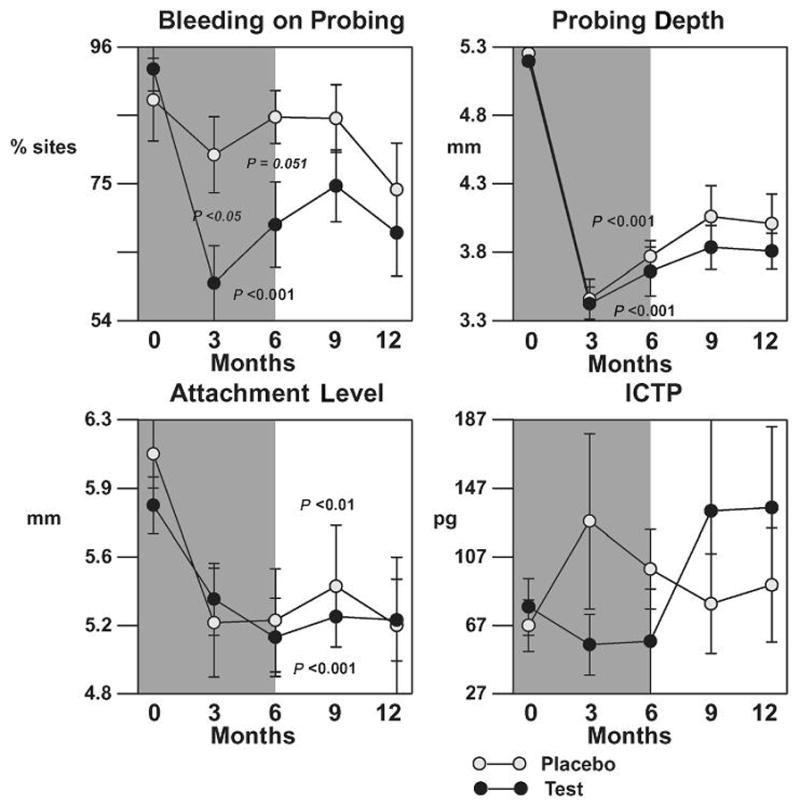

Pooled surgical sites (all probing depth strata)

The mean per-patient averages in BOP, PD, CAL, and ICTP from baseline for all surgical sites are shown in Figure 3. As expected, both placebo and test groups demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in PD compared to baseline (P <0.001); however, no differences between groups were found. Surgical therapy resulted in mean CAL gains in both groups (P >0.05). The LDD group demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in percentage of BOP sites at 3 and 6 months compared to baseline (25% to 60%, P <0.05) while in the placebo group, no statistical significance was found (~15%, P >0.05). In addition, the LDD group demonstrated a decreased but not statistically significant expression of GCF ICTP levels compared to placebo during the drug administration period.

Figure 3.

Effect of LDD or placebo in combination with surgery on clinical parameters and ICTP for all sites receiving surgery. The shaded background indicates time of drug or placebo administration. The bars represent per-patient standard errors. P values indicate significant changes over time within a treatment as determined by the Quade test.

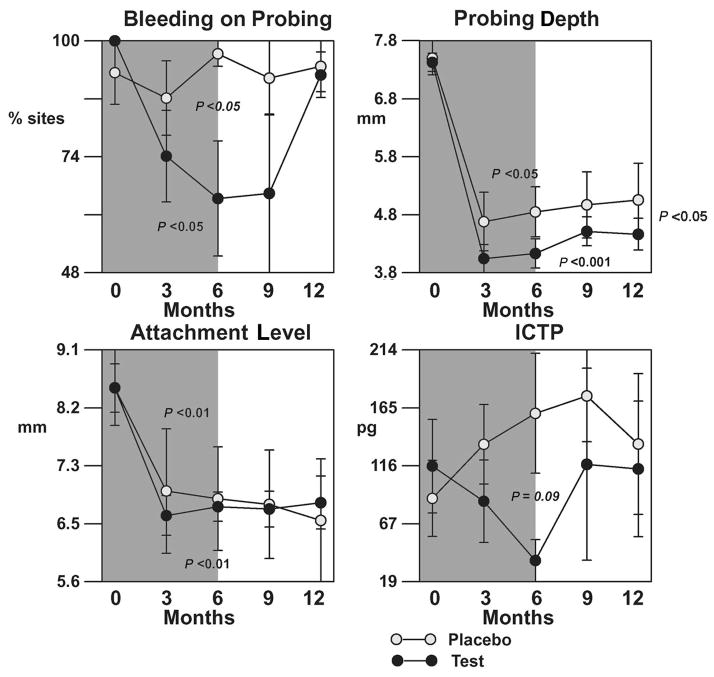

Moderate sites (baseline PD 5 to 6 mm)

Mean per-patient averages in BOP, PD, CAL, and ICTP levels from baseline at surgical sites with a baseline PD of 5 to 6 mm are shown in Figure 4. Consistent with results from pooled PD strata, there were significant reductions in PD and gains in CAL compared to baseline for both drug and control groups, while no statistical difference between treatments was found although trends for a drug effect for PD reduction were noted. ICTP levels were reduced while patients were on LDD therapy, but a rebound in ICTP levels in the LDD + AFS group was demonstrated after patients discontinued the drug. There was a statistically significant reduction in the percent of BOP sites at 3 and 6 months compared to baseline in the LDD + AFS group (P <0.05), while no such effect was seen in patients receiving placebo capsules (P >0.05). Both LDD + AFS and placebo + AFS groups showed comparable levels in percentage of sites BOP after the patients discontinued drug therapy (P >0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect of LDD or placebo in combination with surgery on clinical parameters and ICTP levels for initial pockets of 5 to 6 mm. The shaded background indicates period of drug or placebo administration. The bars represent per-patient standard errors. P values indicate significant changes over time within a treatment as determined by the Quade test.

Deep sites (baseline PD ≥7 mm)

Figure 5 shows the mean per-patient averages in BOP, PD, CAL, and ICTP levels for initially deep sites. Greater reductions in PD were noted in this stratum for both groups. Drug therapy resulted in more statistically significant reduction in PD in deep sites compared to controls (P <0.05) and this difference was sustained for the duration of the study. However, no differences were found between groups with respect to CAL. In addition, patients receiving LDD + AFS showed greater reductions in ICTP levels compared to placebo + AFS during the first 6-month observation period, but no statistical differences were found (P = 0.09). This difference was also not significant when patients discontinued drug therapy. Again, LDD therapy resulted in a statistical reduction in the percent of BOP sites (P <0.05) for 6 months while no such reductions were demonstrated in placebo controls (P >0.05). However, these differences between groups were not significant by the end of the trial (P >0.05).

Figure 5.

Effect of LDD or placebo in combination with surgery on clinical parameters and ICTP for initial pocket of ≥7 mm. The shaded background indicates time of drug or placebo administration. The bars represent per-patient standard errors. P values indicate significant changes over time within a treatment as determined by the Quade test.

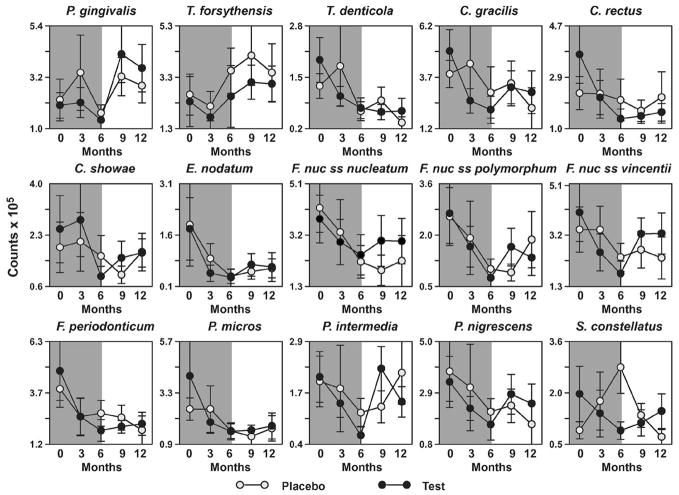

Microbial Outcomes

Comparisons between LDD + AFS and placebo + AFS were performed utilizing mean microbial DNA counts of each microorganism averaged per patient and then per group. When interanalysis was performed, no statistically significant differences were found for any of the 40 microorganisms tested at any given time point (data not shown). There was an immediate reduction in red complex and orange complex species in both drug and placebo groups after AFS was performed (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of surgery with and without adjunctive LDD therapy on the subgingival microflora. Microbial analyses were performed for the presence and levels of 40 subgingival pathogens utilizing whole genomic DNA probes and checkerboard DNA-DNA hybridization. The mean count for each species was computed per patient and then averaged across patients. Time points in each graph represent baseline; 3 months; 6 months; 9 months and 12 months, respectively. The shaded background indicates time of drug or placebo administration. Significant differences over time were determined using the Quade test, and no differences between groups were detected by the Mann-Whitney test. SEM = standard error of the means.

Gelatin Zymography for Proteinase Expression

Five patients (two LDD and three placebo) completed baseline and 2 months harvest of gingival tissues for gelatin zymography analysis. After tissue preparation, zymograms were run in a standard manner, utilizing commercially available collagenases type IV as a positive control. Results generated from all patients demonstrated that a downregulation in gelatinase activity (mean 7.2%; range: 4.9% to 8.5%) in patients receiving adjunctive therapy, while an increase in activity was seen in the placebo group (mean 5.6%; range: −10.4% to 17.5%).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present investigation was to attempt to unravel biological changes that occur as a result of a combination of periodontal therapies with antibacterial effects (i.e., surgery) and host modulatory effects (i.e., LDD). The consideration of the bacterial-host interaction as a basic mechanism for periodontitis pathogenesis has driven the concept that successful long-term management of this disease may be dependent upon an effective control of bacterial load in combination with host modulatory therapies. To date, several bone-sparing agents or host modulatory drugs have been developed to control pathways responsible for periodontal tissue breakdown such as regulation of immune32,33 and inflammatory responses,34–37 excessive production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs),8,10,38 arachidonic acid metabolites,39–42 and regulation of bone metabolism.43,44

This pilot investigation sought to evaluate the potential additive effect of LDD to modulate wound repair in conjunction with periodontal surgery. The goal was to explore the clinical, microbial, and biochemical impact of this drug on the modulation of wound healing post-surgically. Following mechanical therapy in the form of SRP, patients received access flap surgery and were randomized to LDD or placebo groups for 6 months of drug therapy, followed by a 6-month post-dosing evaluation. As expected, both therapies led to significant clinical improvements in terms of PD reduction and CAL gain (Figs. 3, 4, and 5). Patients in the placebo + AFS showed probing depth reductions and clinical attachment level gains similar to previously reported longitudinal studies, when the same therapy was compared.45,46

Tetracycline analogues have been some of the most extensively investigated host modulatory agents and specifically, the low dose regimen of doxycycline hyclate (20 mg b.i.d.).6 Both preclinical and human clinical data have shown that tetracycline can suppress MMPs,8,10,38 which are considered to be primary enzymes responsible for the destruction of extracellular matrix macromolecules. Investigators have demonstrated the effects of adjunctive LDD in conjunction with supragingival scaling and dental prophylaxis,47–49 and SRP.15,17,50 Caton et al.17 indicated that a 9-month course of LDD with SRP resulted in statistically significant improvements in PD reduction and CAL gains when compared with placebo controls. The effects were maintained 12 months after initial therapy.50

In this study, clinical efficacy was examined at sites with baseline PDs of 1 to 4 mm for shallow sulci/pockets (data not shown), 5 to 6 mm for moderate pockets (Fig. 4), and ≥7 mm for deep pockets (Fig. 5). This allowed analysis of the effects of LDD at sites fulfilling the criteria for periodontal surgery (i.e., PD ≥5 mm). In addition, the patients exhibited moderate to severe horizontal bone loss that is generally not indicated for traditional regenerative therapy. Therefore, patients included in this trial exhibited bone loss patterns with limited treatment options (non-surgical therapy or pocket reduction/elimination surgery). Although the present investigation was not designed as a definitive clinical trial, our results suggested a number of intriguing leads. When LDD was administered in combination with AFS, a greater probing depth reduction was found in deep sites of AFS + LDD subjects compared to controls (Fig. 5, P <0.05). This result was maintained 6 months after discontinuation of the drug (Fig. 5, P <0.05). However, no statistically significant differences between randomized groups were noted for CAL in any of the probing depth strata. There may be potential mechanisms that explain the PD reduction seen with LDD therapy: LDD therapy may promote more rapid wound maturation by inhibiting collagen disruption and indirectly encouraging collagen formation. Therefore, differences in timing, quality, and quantity of wound contraction in the periodontal tissues might have promoted additional PD reduction in the drug group.

The results of this study revealed a significant reduction in percentage of sites exhibiting BOP when patients were taking LDD as compared to the placebo group (Figs. 3, 4, and 5). These results are in agreement with a previous investigation,17 where a reduction in bleeding sites was seen in patients receiving adjunctive LDD compared to placebo. By contrast, Golub et al.9 reported only minimal and non-significant reductions in gingival inflammation and bleeding index51 with the use of LDD. In that study,9 the authors suggest that the improvement in periodontal conditions by LDD therapy was mainly by inhibiting collagen-destructive enzymes rather than affecting microbially-induced inflammation.9 However, it is important to note that the effects of LDD on BOP in our investigation also appeared to be independent of microbial shifts. Therefore, the effects of LDD on gingival inflammation (i.e., BOP) need to be further evaluated. In addition, it should be noted that both placebo and test groups experienced high BOP frequency at 12 months when deep probing depths were considered. The reason for that lies in the fact that the majority of patients were surgically treated only in the tested quadrant. In other words, remaining pockets after initial therapy on other quadrants might have served as reservoirs of putative bacteria that potentially infected the surgically-treated pockets. These findings have been confirmed by other investigations which reported that a natural recolonization of pathogenic microorganisms occurs after periodontal therapy.52–54 Therefore, this aspect could explain the high frequency of BOP in deep sites as well as recolonization of putative microorganisms found in this investigation (e.g., Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Pre-votella intermedia).

LDD + AFS resulted in a decrease in the putative bone resorption marker ICTP soon after the surgical therapy at 3 months while placebo controls demonstrated no change or increases in ICTP levels over the 12-month observation period. ICTP reflects the amount of organic matrix being disrupted in alveolar bone (specifically, type I collagen) following osteoclastic bone resorption. Human histological data have shown that osteoclastic activity peaks immediately after a surgical procedure is performed and is then followed by bone formation.55 Therefore, release of excessive osteoclastic collagenases (or MMP-13) may have increased the disruption of collagen type I in bone and consequently increased ICTP release in the placebo + AFS group. Golub et al.8 have demonstrated a direct effect of LDD therapy on the reduction of excessive MMP-13 followed by a concomitant decline in levels of collagen degradation fragments. In addition, it has been demonstrated that the increased circulating concentration of ICTP was most likely produced by action of MMPs.56 In the same study, cathepsin K-mediated bone resorption (an osteoclastic cysteine protease) destroyed ICTP antigenicity, further showing the specificity of MMPs on the initial disruption of bone collagen.56 Hence, our findings have demonstrated that utilization of an MMP inhibitor may have a direct impact on postsurgical bone turnover. This result supports the notion that decreased collagenolytic activity (via LDD) can reduce bone resorption and act as a bone-sparing agent. Although these results are from only a small subset of patients from our investigation, these findings should encourage further exploration of the impact of host modulatory agents on bone maintenance.

With regard to the issue of low-dose antibiotics possibly resulting in direct microbial shifts, our study found no statistically significant differences between drug and control groups at any time point for any of the 40 tested species. These results are in agreement with previous human trials.57,58 It should also be noted that only surgical sites were evaluated for microbial analysis, therefore, effects of this drug on other sites are not available. When the data were analyzed according to bacterial complexes as proposed by Socransky et al.,31 a reduction in periodontal pathogenic organisms was found in both groups, and this outcome was attributed to the effects of periodontal surgery. These findings are in concordance with recent reports59,60 that suggest that there is a beneficial effect of surgery on suppression of periodontal pathogens by eliminating reservoirs of virulent organisms. However, effects of continuous administration or cyclical dosing of LDD + surgery on microbial resistance or shifts were not evaluated in this study.

This investigation demonstrated no differences between groups regarding drug compliance. The overall compliance was approximately 80% with small tendencies for the patients to be more compliant in the morning and in the first 3 months of the drug administration period (NS; P >0.05). In our study, a wide range of compliance was found (18% to 100%) but it was also demonstrated that the majority of patients were reasonably compliant with the 6-month b.i.d. regimen (over 90% were >70% compliant).

CONCLUSIONS

Six-month administration of LDD suggests that there is an enhanced postsurgical wound healing compared to placebo controls with regard to PD reduction. This positive effect was most marked in deep sites (≥7 mm), where the differences in PD reduction were maintained until the completion of the trial. Reductions in the bone resorption marker ICTP were also found in patients while on the drug, suggesting the potential of LDD to act as a bone-sparing agent. In addition, the percentage of BOP sites was affected by LDD therapy, but this effect was only noticeable during the period of the drug administration. Finally, no significant shifts on the periodontal microbiota beyond that attributable to the effects of the surgery could be seen with the utilization of LDD.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Drs. Qiming Jin, Amin ur Rahman, and Khalaf Al-Shammari during early stages of the investigation while at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. The authors also appreciate the technical assistance of Denise Guerrero and Tina Yaskell, The Forsyth Institute, Boston, Massachusetts. We acknowledge Dr. Lorne Golub, State University of New York at Stony Brook, for critically reading the manuscript. This study was supported by NIH/NIDCR grants 5T35 DE07101, DE10977, and DE12861; CollaGenex Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Newtown, Pennsylvania; and the Delta Dental Fund of Michigan.

Footnotes

Periostat, CollaGenex Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Newtown, PA.

Vicryl, Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ.

Periopaper, IDE-Interstate, Amityville, NY.

DiaSorin, Inc., Stillwater, MN.

BCA Protein Assay Reagent, Pierce, Rockford, IL.

Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA.

References

- 1.Page RC. The role of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J Periodont Res. 1991;26:230–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1991.tb01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Microbial mechanisms in the pathogenesis of destructive periodontal diseases: A critical assessment. J Periodont Res. 1991;26:195–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1991.tb01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slots J, Genco RJ. Black-pigmented Bacteroides species, Capnocytophaga species, and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease: Virulence factors in colonization, survival, and tissue destruction. J Dent Res. 1984;63:412–421. doi: 10.1177/00220345840630031101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gopalsami C, Yotis W, Corrigan K, Schade S, Keene J, Simonson L. Effect of outer membrane of Treponema denticola on bone resorption. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1993;8:121–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1993.tb00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golub LM, Siegel K, Ramamurthy NS, Mandel ID. Some characteristics of collagenase activity in gingival crevicular fluid and its relationship to gingival diseases in humans. J Dent Res. 1976;55:1049–1057. doi: 10.1177/00220345760550060701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golub LM, Ciancio S, Ramamamurthy NS, Leung M, McNamara TF. Low-dose doxycycline therapy: Effect on gingival and crevicular fluid collagnase activity in humans. J Periodont Res. 1990;25:321–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1990.tb00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorsa T, Uitto VJ, Suomalainen K, Vauhkonen M, Lindy S. Comparison of interstitial collagenases from human gingiva, sulcular fluid and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Periodont Res. 1988;23:386–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1988.tb01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golub LM, Lee HM, Greenwald RA, et al. A matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor reduces bone-type collagen degradation fragments and specific collagenases in gingival crevicular fluid during adult periodontitis. Inflamm Res. 1997;46:310–319. doi: 10.1007/s000110050193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golub LM, McNamara TF, Ryan ME, et al. Adjunctive treatment with subantimicrobial doses of doxycycline: Effects on gingival fluid collagenase activity and attachment loss in adult periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:146–156. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028002146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golub LM, Lee HM, Lehrer G, et al. Minocycline reduces gingival collagenolytic activity during diabetes. Preliminary observations and a proposed new mechanism of action. J Periodont Res. 1983;18:516–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1983.tb00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golub LM, McNamara TF, D’Angelo G, Greenwald RA, Ramamurthy NS. A non-antibacterial chemically-modified tetracycline inhibits mammalian collagenase activity. J Dent Res. 1987;66:1310–1314. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660080401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu LP, Jr, Smith GN, Jr, Brandt KD, Myers SL, O’Connor BL, Brandt DA. Reduction of the severity of canine osteoarthritis by prophylactic treatment with oral doxycycline. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:1150–1159. doi: 10.1002/art.1780351007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorsa T, Lindy O, Konttinen YT, et al. Doxycycline in the protection of serum alpha-1-antitrypsin from human neutrophil collagenase and gelatinase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:592–594. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.3.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golub LM, Lee HM, Ryan ME, Giannobile WV, Payne J, Sorsa T. Tetracyclines inhibit connective tissue breakdown by multiple non-antimicrobial mechanisms. Adv Dent Res. 1998;12:12–26. doi: 10.1177/08959374980120010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novak MJ, Johns LP, Miller RC, Bradshaw MH. Adjunctive benefits of subantimicrobial dose doxycycline in the management of severe, generalized, chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2002;73:762–769. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.7.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crout RJ, Lee HM, Schroeder K, et al. The “cyclic” regimen of low-dose doxycycline for adult periodontitis: A preliminary study. J Periodontol. 1996;67:506–514. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.5.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caton JG, Ciancio SG, Blieden TM, et al. Treatment with subantimicrobial dose doxycycline improves the efficacy of scaling and root planing in patients with adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:521–532. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.4.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarlton JF, Vickery CJ, Leaper DJ, Bailey AJ. Postsurgical wound progression monitored by temporal changes in the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:506–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb03779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soo C, Shaw WW, Zhang X, Longaker MT, Howard EW, Ting K. Differential expression of matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue-derived inhibitors in cutaneous wound repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:638–647. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200002000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simeon A, Monier F, Emonard H, et al. Expression and activation of matrix metalloproteinases in wounds: Modulation by the tripeptide-copper complex glycyl-L-histidyl-L-lysine-Cu2+ J Invest Dermatol. 1999;112:957–964. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neely AN, Clendening CE, Gardner J, Greenhalgh DG. Gelatinase activities in wounds of healing-impaired mice versus wounds of non-healing-impaired mice. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2000;21:395–402. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200021050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu Q, Wang D, Gao Y, et al. Expression of MMP1 in surgical and radiation-impaired wound healing and its effects on the healing process. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2002;21:71–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agren MS, Taplin CJ, Woessner JF, Jr, Eaglstein WH, Mertz PM. Collagenase in wound healing: Effect of wound age and type. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:709–714. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12614202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lobmann R, Ambrosch A, Schultz G, Waldmann K, Schiweck S, Lehnert H. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in the wounds of diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1011–1016. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0868-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi H, Akiba K, Noguchi T, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase activity is enhanced during corneal wound repair in high glucose condition. Curr Eye Res. 2000;21:608–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craig RG, Yu Z, Xu L, et al. A chemically modified tetracycline inhibits streptozotocin-induced diabetic depression of skin collagen synthesis and steady-state type I procollagen mRNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1402:250–260. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bain S, Ramamurthy NS, Impeduglia T, Scolman S, Golub LM, Rubin C. Tetracycline prevents cancellous bone loss and maintains near-normal rates of bone formation in streptozotocin diabetic rats. Bone. 1997;21:147–153. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Dibart S, Smith C, Kent RL, Jr, Socransky SS. The effect of SRP on the clinical and microbiological parameters of periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:324–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giannobile WV, Lynch SE, Denmark RG, Paquette DW, Fiorellini JP, Williams RC. Crevicular fluid osteocalcin and pyridinoline cross-linked carboxyterminal telopeptide of type I collagen (ICTP) as markers of rapid bone turnover in periodontitis. A pilot study in beagle dogs. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:903–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korostoff JM, Wang JF, Sarment DP, Stewart JC, Feldman RS, Billings PC. Analysis of in situ protease activity in chronic adult periodontitis patients: Expression of activated MMP-2 and a 40 kDa serine protease. J Periodontol. 2000;71:353–360. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL., Jr Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:134–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans RT, Klausen B, Sojar HT, et al. Immunization with Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis fimbriae protects against periodontal destruction. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2926–2935. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2926-2935.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moritz AJ, Cappelli D, Lantz MS, Holt SC, Ebersole JL. Immunization with Porphyromonas gingivalis cysteine protease: Effects on experimental gingivitis and ligature-induced periodontitis in Macaca fascicularis. J Periodontol. 1998;69:686–697. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.6.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lohinai Z, Benedek P, Feher E, et al. Protective effects of mercaptoethylguanidine, a selective inhibitor of inducible nitric oxide synthase, in ligature-induced periodontitis in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:353–360. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christman JW, Lancaster LH, Blackwell TS. Nuclear factor kappa B: A pivotal role in the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and new target for therapy. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:1131–1138. doi: 10.1007/s001340050735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lum RT, Kerwar SS, Meyer SM, et al. A new structural class of proteasome inhibitors that prevent NF-kappa B activation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:1391–1397. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou L, Pope BL, Chourmouzis E, Fung-Leung WP, Lau CY. Tepoxalin blocks neutrophil migration into cutaneous inflammatory sites by inhibiting Mac-1 and E-selectin expression. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:120–129. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golub LM, Sorsa T, Lee HM, et al. Doxycycline inhibits neutrophil (PMN)-type matrix metalloproteinases in human adult periodontitis gingiva. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:100–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nyman S, Schroeder HE, Lindhe J. Suppression of inflammation and bone resorption by indomethacin during experimental periodontitis in dogs. J Periodontol. 1979;50:450–461. doi: 10.1902/jop.1979.50.9.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams RC, Jeffcoat MK, Howell TH, et al. Indomethacin or flurbiprofen treatment of periodontitis in beagles: Comparison of effect on bone loss. J Periodontal Res. 1987;22:403–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1987.tb01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams RC, Jeffcoat MK, Kaplan ML, Goldhaber P, Johnson HG, Wechter WJ. Flurbiprofen: A potent inhibitor of alveolar bone resorption in beagles. Science. 1985;227:640–642. doi: 10.1126/science.3969553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kornman KS, Blodgett RF, Brunsvold M, Holt SC. Effects of topical applications of meclofenamic acid and ibuprofen on bone loss, subgingival microbiota and gingival PMN response in the primate Macaca fascicularis. J Periodontal Res. 1990;25:300–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1990.tb00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fleisch H. Bisphosphonates. Pharmacology and use in the treatment of tumour-induced hypercalcaemic and metastatic bone disease. Drugs. 1991;42:919–944. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199142060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brunsvold MA, Chaves ES, Kornman KS, Aufdemorte TB, Wood R. Effects of a bisphosphonate on experimental periodontitis in monkeys. J Periodontol. 1992;63:825–830. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.10.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramfjord SP, Caffesse RG, Morrison EC, et al. Four modalities of periodontal treatment compared over five years. J Periodontal Res. 1987;22:222–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1987.tb01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaldahl WB, Kalkwarf KL, Patil KD, Molvar MP, Dyer JK. Long-term evaluation of periodontal therapy: I Response to 4 therapeutic modalities. J Periodontol. 1996;67:93–102. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bouwsma O, Payonk G, Baron H, Sipos T. Low-dose doxycycline effects on clinical parameters in adult periodontitis. J Dent Res. 1992;71(Spec Issue):245. (Abstr. 1119) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caton JG, Blieden T, Adams D, et al. Subantimicrobial doxycycline therapy for periodontitis. J Dent Res. 1997;77(Spec Issue):177. (Abstr. 1307) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ciancio S, Ashley R. Safety and efficacy of sub-antimicrobial-dose doxycycline therapy in patients with adult periodontitis. Adv Dent Res. 1998;12:27–31. doi: 10.1177/08959374980120011501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caton JG, Ciancio SG, Blieden TM, et al. Subantimicrobial dose doxycycline as an adjunct to scaling and root planing: Post-treatment effects. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:782–789. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.280810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caton JG, Polson AM. The interdental bleeding index: A simplified procedure for monitoring gingival health. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1985;6:88,90–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slots J, Mashimo P, Levine MJ, Genco RJ. Periodontal therapy in humans. I Microbiological and clinical effects of a single course of periodontal scaling and root planing, and of adjunctive tetracycline therapy. J Periodontol. 1979;50:495–509. doi: 10.1902/jop.1979.50.10.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sbordone L, Ramaglia L, Gulletta E, Iacono V. Recolonization of the subgingival microflora after scaling and root planing in human periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1990;61:579–584. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.9.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lavanchy DL, Bickel M, Baehni PC. The effect of plaque control after scaling and root planing on the subgingival microflora in human periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:295–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilderman MN, Pennel BM, King K, Barron JM. Histogenesis of repair following osseous surgery. J Periodontol. 1970;41:551–565. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.10.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sassi ML, Eriksen H, Risteli L, et al. Immunochemical characterization of assay for carboxyterminal telopeptide of human type I collagen: Loss of antigenicity by treatment with cathepsin K. Bone. 2000;26:367–373. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(00)00235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomas J, Walker C, Bradshaw M. Long-term use of subantimicrobial dose doxycycline does not lead to changes in antimicrobial susceptibility. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1472–1483. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.9.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walker C, Thomas J, Nango S, Lennon J, Wetzel J, Powala C. Long-term treatment with subantimicrobial dose doxycycline exerts no antibacterial effect on the subgingival microflora associated with adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1465–1471. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.9.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levy RM, Giannobile WV, Feres M, Haffajee AD, Smith C, Socransky SS. The effect of apically repositioned flap surgery on clinical parameters and the composition of the subgingival microbiota: 12-month data. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2002;22:209–219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Levy RM, Giannobile WV, Feres M, Haffajee AD, Smith C, Socransky SS. The short-term effect of apically repositioned flap surgery on the composition of the subgingival microbiota. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1999;19:555–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]