Abstract

When the heart fails, there is often a constellation of biochemical alterations of the β-adrenergic receptor (βAR) signaling system, leading to the loss of cardiac inotropic reserve. βAR down-regulation and functional uncoupling are mediated through enhanced activity of the βAR kinase (βARK1), the expression of which is increased in ischemic and failing myocardium. These changes are widely viewed as representing an adaptive mechanism, which protects the heart against chronic activation. In this study, we demonstrate, using in vivo intracoronary adenoviral-mediated gene delivery of a peptide inhibitor of βARK1 (βARKct), that the desensitization and down-regulation of βARs seen in the failing heart may actually be maladaptive. In a rabbit model of heart failure induced by myocardial infarction, which recapitulates the biochemical βAR abnormalities seen in human heart failure, delivery of the βARKct transgene at the time of myocardial infarction prevents the rise in βARK1 activity and expression and thereby maintains βAR density and signaling at normal levels. Rather than leading to deleterious effects, cardiac function is improved, and the development of heart failure is delayed. These results appear to challenge the notion that dampening of βAR signaling in the failing heart is protective, and they may lead to novel therapeutic strategies to treat heart disease via inhibition of βARK1 and preservation of myocardial βAR function.

The molecular alterations that take place in the β-adrenergic receptor (βAR) system during the progression of heart failure (HF) are well characterized (1). As the heart begins to fail, compensatory mechanisms are initiated to maintain cardiac output and systemic blood pressure. One of these mechanisms involves the sympathetic nervous system, which increases its outflow of norepinephrine to the heart in an attempt to stimulate contractility (2), which can lead to βAR desensitization and down-regulation. Reduction of cardiac βAR density in the failing human heart was first observed by Bristow et al. in 1982 (3). β1ARs have been shown to be selectively reduced as β2ARs are not altered (4, 5). However, all remaining βARs in the failing heart appear desensitized (3). βAR kinase (βARK1), a member of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK) family that is responsible for rapidly regulating G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) function by phosphorylation (6), appears to play a central role in the desensitization and down-regulation of βARs in the failing heart, as its expression and activity are significantly elevated in human HF (5). This up-regulation of βARK1 has also been observed in several animal models of HF and actually precedes the development of hemodynamic failure (7–9). Moreover, βARK1 is also elevated in several other cardiovascular disorders, including hypertension (10), cardiac hypertrophy (11), and myocardial ischemia (12, 13).

Catecholamines are increased, but functional responsiveness to catecholamines is depressed in the ischemic and failing heart, suggesting that increased myocardial βARK1 and the resultant desensitization of βARs might represent an adaptive mechanism that can act to protect the heart against chronic activation (1, 14). Apparently supporting this interpretation is the fact that one of the most promising current therapies in HF is the use of βAR antagonists, which presumably block the chronic activation of the βAR system by norepinephrine (15, 16). βARK1 up-regulation could be the “first-response” feedback mechanism responding to the enhanced sympathetic nervous system activity because the expression of βARK1 in the heart can be stimulated by catecholamine exposure (17). An opposing hypothesis, however, is that the increase in myocardial GRK activity often observed in the failing heart can mediate changes within the βAR system that are not protective but that rather take part in the pathogenesis of HF. If such is the case, then the inhibition of βARK1 might represent a novel therapeutic target in the treatment of the failing heart.

To address specifically the issue of whether βAR desensitization might have maladaptive rather than adaptive consequences in the setting of HF, we have delivered a peptide inhibitor of βARK1 activity via in vivo intracoronary adenoviral-mediated gene delivery to the hearts of rabbits that have a surgically induced myocardial infarction (MI). We have shown previously that this model of MI in rabbits results in overt HF within 3 weeks, including pleural effusions, ascites, and significant hemodynamic dysfunction (13). The βARK1 inhibitor used is the last 194 amino acids of βARK1 (βARKct), which contains the domain responsible for binding to the βγ-subunits of activated G proteins (Gβγ), a process required for the activation of endogenous βARK1 (18). By delivering the βARKct peptide to the infarcted heart, we have been able to assess myocardial βAR signaling alterations and indices of physiologic function in a temporal manner after the onset of ischemia and thus to address whether these changes alter the progression of HF in a favorable or unfavorable fashion.

Methods

Adenoviral Transgenes and in Vivo Intracoronary Delivery.

The adenoviral backbone for Adeno-βARKct and empty adenoviral vector (EV) were a second generation replication-deficient serotype 2 adenovirus with deletions of the E1 and E4 (except for ORF6) as previously described (19). Animals used in this study were adult male New Zealand White rabbits (1–3 kg), and all procedures were performed in accordance with the regulations adopted by the National Institutes of Health and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Duke University. Normal rabbits underwent intracoronary gene delivery as we have previously described (20). This procedure involves a right thoracotomy in anesthetized intubated rabbits, and the adenovirus (in 1.5 ml PBS) is rapidly injected via a needle catheter into the left ventricular (LV) chamber while the aorta is crossclamped for 40 sec. Before gene delivery, a bolus of adenosine (0.75 mg/kg) is delivered into the right ventricular chamber (20).

Coronary Artery Ligation and Adenoviral-Mediated Gene Delivery.

To deliver transgenes before MI, rabbits were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (50 mg/kg) and acepromazine (0.05 mg/kg), intubated, and mechanically ventilated. A left thoracotomy was performed through the fourth intercostal space, the pericardium was opened, and blunt dissection was used to encircle the pulmonary artery with a 2–0 silk ligature to retract it and gain access to the aorta for crossclamping. Intracoronary gene (or PBS) delivery then proceeded as described above, and MI was then produced via the ligation of a marginal branch of the left circumflex coronary artery (LCx), as we have previously described, using 5–0 prolene suture (13). Bretylium (5 mg/kg) was administered for arrhythmia prophylaxis. Control animals underwent a sham operation. Operative mortality was 20% and did not differ between treatment groups. For characterization of infarction size, hearts were dissected after euthanasia and rinsed in saline, and the LV free wall was cut away. Infarct size, as a percentage of the LV free wall surface area, was determined by tracing the LV free wall on a piece of paper, tracing the infarcted area, and weighing the pieces of paper.

In Vivo Hemodynamic Measurements.

To measure in vivo hemodynamic data in conscious animals, rabbits were lightly sedated with ketamine (30 mg/kg) and acepromazine (0.05 mg/kg). The right carotid artery was then exposed, and a 2.5-French micromanometer (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was advanced into the LV cavity to record pressures and heart rate as previously described (20). Data were obtained at baseline and where indicated after infusions of isoproterenol (Iso).

Radioligand Binding.

Myocardial membranes were prepared from frozen hearts as described previously (20). Final purified cardiac membranes were suspended at a concentration of 1–2 mg/ml, and receptor binding was performed by using the nonselective βAR ligand [125I] cyanopindolol. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 20 μM alprenolol. All assays were performed in triplicate, and receptor density (measured in fmol) was normalized to milligrams of membrane protein.

Membrane Adenylyl Cyclase Activity.

Myocardial membranes were prepared as above and incubated (20 μg protein) for 15 min at 37°C with [α-32P]ATP under basal conditions or in the presence of either 100 μM Iso or 10 mM NaF, and cAMP was quantitated by standard methods that we have described (20, 21).

Protein Immunoblotting.

Immunodetection of myocardial βARKct expression was carried out on cytosolic extracts prepared from homogenized rabbit hearts as we have previously described (21). Myocardial βARK1 levels were detected by immunoblotting for βARK1 after immunoprecipitation from myocardial extracts by using a monoclonal antibody as previously described (13, 17).

GRK Activity Assays.

Assessment of myocardial GRK activity was carried out by using cytosolic extracts and rhodopsin-enriched rod outer segment membranes as we have previously described (13, 17). 32P incorporation into the rhodopsin substrate was quantified from dried gels by using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager as described (13, 17).

Northern Analysis.

Hearts from the various experimental animals were excised, total RNA was isolated, and Northern blot analysis was carried out by standard methods previously described (20).

Statistical Analysis.

Data are presented as mean ±SEM. Comparisons between two groups were made with a Student's t test, whereas comparisons among the same animals at different times were analyzed with a paired t test. Iso dose-response data between groups were analyzed by single-factor ANOVA with repeated measures, by using Neuman–Keuls post hoc analysis when appropriate. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

βARKct Gene Delivery to Healthy Rabbits.

To investigate the effects of acute βARK1 inhibition in normal myocardium, either the βARKct transgene (Adeno-βARKct) or an EV was delivered to the hearts of healthy rabbits via the in vivo delivery method that we have developed recently (20). This method involves injection of adenovirus directly into the LV cavity while the aorta is crossclamped for 40 sec. Delivery of 5 × 1011 total viral particles (tvp) of Adeno-βARKct (n = 6) resulted in expression of the βARKct in all chambers of the rabbit heart 7 days after gene delivery (Fig. 1 A and B). The presence of βARKct was found neither in EV-treated rabbits (n = 6) nor in rabbits receiving PBS (n = 6). Rabbits receiving Adeno-βARKct had significant improvements in several in vivo hemodynamic measurements 7 days after gene delivery compared with EV-treated controls (Table 1). Of particular importance, βARKct-expressing rabbits had enhanced cardiac contractility, as assessed by the maximal rate of LV pressure rise (LV dP/dtmax), measured both at baseline and after stimulation with the β-agonist Iso (Table 1). Furthermore, baseline LV end-diastolic pressure (EDP) was significantly lower in rabbits expressing βARKct (−2.9 ± 0.4 mmHg) compared with the EV-treated controls (3.9 ± 2.2 mmHg, P < 0.005). In addition, hemodynamic measurements, including dP/dtmax, in Adeno-βARKct-treated rabbits were significantly enhanced compared with rabbits treated with PBS (data not shown).

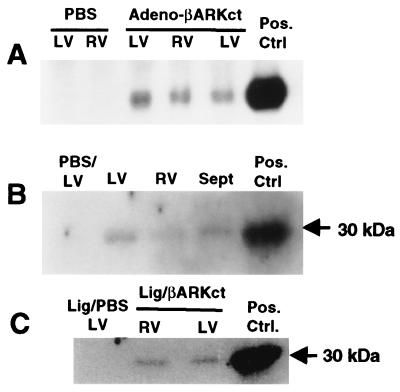

Figure 1.

βARKct expression after in vivo adenoviral-mediated intracoronary transgene delivery of 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-βARKct. (A) Northern analysis of βARKct mRNA from total RNA isolated from representative Adeno-βARKct and PBS-treated rabbit hearts. (B) βARKct peptide expression in the normal heart as visualized via a Western blot of representative cardiac extracts from Adeno-βARKct and PBS-treated rabbit hearts. (C) Representative Western blot of extracts from infarcted rabbit hearts that received PBS or Adeno-βARKct before LCx ligation. The positive control was RNA or protein isolated from cultured cardiomyocytes infected with Adeno-βARKct.

Table 1.

In vivo hemodynamic measurements in normal rabbits treated with 5 × 1011 tvp of Adeno-βARKct compared with Adeno-EV-treated rabbits

| Adeno-βARKct

|

Adeno-EV

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | Iso 0.1 | Iso 0.5 | Iso 1.0 | Basal | Iso 0.1 | Iso 0.5 | Iso 1.0 | |

| LVdP/dtmax*, mmHg/s | 3,623 ± 312† | 5,192 ± 283† | 6,286 ± 225† | 6,354 ± 285† | 2,054 ± 81 | 3,793 ± 163 | 4,616 ± 292 | 4,185 ± 320 |

| LVdP/dtmin, mmHg/s | −2,399 ± 215 | −2,827 ± 240 | −2,840 ± 191 | −2,992 ± 247 | −1,815 ± 136 | −2,405 ± 110 | −2,545 ± 110 | −2,301 ± 147 |

| LVSP, mmHg | 61 ± 3.3 | 67.2 ± 2.3 | 71.7 ± 2.4 | 73.6 ± 3.5 | 57.2 ± 2.4 | 63.7 ± 1.4 | 64.9 ± 2.2 | 61.6 ± 2.5 |

| HR, bpm | 243 ± 8.1 | 297 ± 8.1 | 322 ± 6.4 | 329 ± 5.8 | 231 ± 8.2 | 263 ± 11 | 295 ± 11 | 301 ± 12 |

*, P < 0.001 vs. EV for between-groups main effect (ANOVA with repeated measures); †, P < 0.0001 vs. EV for specific dose (Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis). Iso, μg/kg/min; LV dP/dtmax, maximal rate of left ventricle (LV) pressure rise; LV dP/dtmin, maximal rate of LV pressure decline; LVSP, LV systolic pressure. HR, bpm, heart rate, beats per minute. n = 6.

Effects of βARKct Expression on Acute βAR Signaling After MI.

We successfully adapted this method of in vivo myocardial gene delivery to rabbits undergoing surgical ligation of a marginal branch of the LCx, which produces MI. Gene delivery to the infarcted heart was accomplished by the intracoronary delivery of Adeno-βARKct immediately before LCx ligation during the same surgical procedure. The distribution of βARKct transgene expression in the infarcted rabbit heart was global in nature (Fig. 1C). Previously in rabbits, we have observed that after 3 weeks, MI reproducibly results in hemodynamic HF with a recapitulation of the βAR signaling changes observed in human HF (13). To determine the time course of βAR signaling changes, LCx-ligated rabbits treated with PBS were randomized to hemodynamic and biochemical study at day 3 (n = 8) or day 7 (n = 12) after MI. The myocardial biochemistry of these infarcted rabbits was compared with βAR properties seen in MI rabbits treated with 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-βARKct (n = 6).

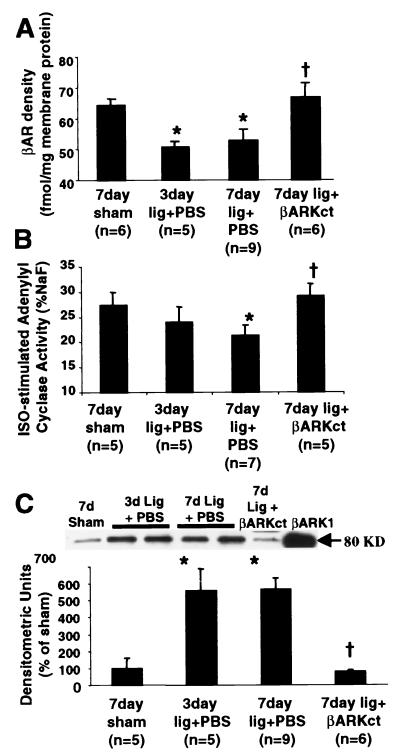

Analysis of myocardial βAR signaling in the infarcted rabbit heart revealed marked impairments as early as 3 days after LCx ligation when compared with sham-operated control animals, and these abnormalities remained or worsened at day 7 after MI (Fig. 2). These significant alterations in βAR signaling in the infarcted heart included a loss in total myocardial βAR density (Fig. 2A), a dampening of βAR signaling as measured by adenylyl cyclase activity (Fig. 2B), and enhanced myocardial βARK1 expression (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, total myocardial GRK activity was also increased (data not shown). Importantly, these changes were observed early after injury in the noninfarcted areas of the LV and the RV, demonstrating global alterations in βAR signaling. Interestingly, all parameters of cardiac βAR signaling were at sham-operated levels in Adeno-βARKct-treated MI rabbits 7 days after LCx ligation, which differs significantly from PBS- and EV-treated infarcted animals (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

βAR signaling after LCx ligation and treatment with either PBS or 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-βARKct. (A) βAR density assessed in purified myocardial membranes and expressed (mean ± SEM) as fmol per milligram of membrane protein. *, P < 0.05 vs. sham; †, P < 0.05 vs. PBS (Student's t test). (B) Myocardial membrane Iso-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity presented (mean ± SEM) as pmol cAMP/min/mg protein and normalized to the activity (%) stimulated by 10 mM NaF. *, P < 0.05 vs. sham; †, P < 0.05 vs. PBS (Student's t test). (C) Myocardial βARK1 protein levels determined by protein immunoblotting of βARK1 immunoprecipitated cardiac cytosolic extracts. (Upper) Representative Western blot for the indicated treatment groups by using purified βARK1 as a positive control. The histograms show the mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.001 vs. sham; †, P < 0.001 vs. PBS (Student's t test).

Hemodynamic Effects of βARKct Expression After MI.

To monitor the development of HF in infarcted rabbits, we assessed hemodynamic parameters after LCx ligation. In rabbits treated with PBS, LV EDP values were significantly elevated at 7 days after MI compared with sham-operated controls [7.8 ± 1.1 mmHg (n = 10) vs. 1.2 ± 1.0 mmHg (n = 5) P < 0.01], indicating that the infarcted hearts were dysfunctional. In a preliminary group of rabbits treated with 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-βARKct (n = 4), LV EDP values 7 days after MI were significantly lower than PBS-treated animals and similar to sham-operated controls (2.6 ± 0.7 mmHg, P < 0.02 vs. PBS-treated MI rabbits).

To expand on these findings, we ligated the LCx in an additional group of rabbits and randomly treated them, in a blinded manner, with 5 × 1011 tvp of EV (n = 15), 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-βARKct (n = 12), or PBS (n = 18) by in vivo intracoronary gene delivery. An additional nine animals underwent a sham operation. In these animals, we assessed in vivo hemodynamics by micromanometer cardiac catheterization at 10 and 20 days after MI. At day 10, baseline cardiac function was measured, and at day 20, both baseline and Iso-stimulated function was assessed. Iso was avoided at day 10 because exposure of infarcted rabbits to catecholamines can cause premature death (data not shown).

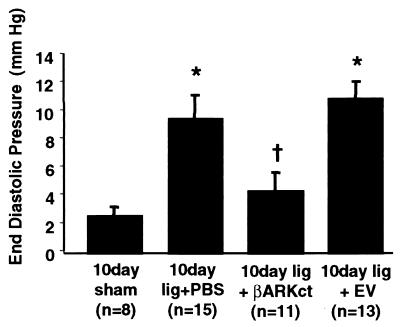

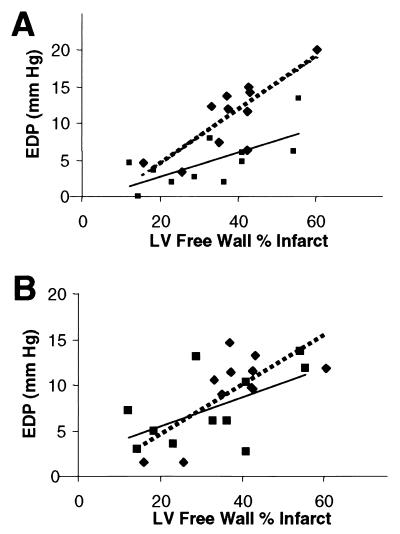

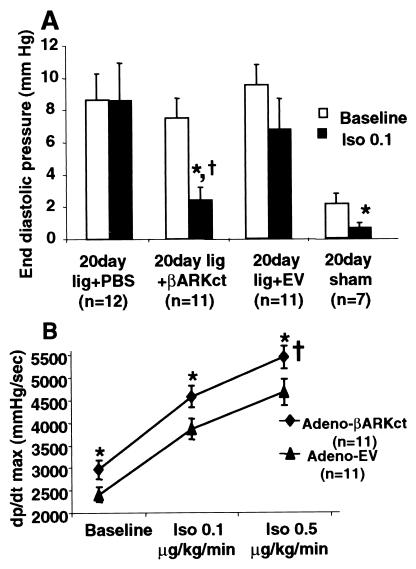

Baseline LV EDP was significantly elevated at day 10 after MI in EV- and PBS-treated MI rabbits when compared with rabbits that received intracoronary delivery of Adeno-βARKct (Fig. 3). As found at 7 days after MI, βARKct expression 10 days after MI resulted in LV EDP values not significantly different from those of sham-operated control rabbits (Fig. 3). Furthermore, when day 10 EDP was plotted vs. infarct size, the regression lines obtained were significantly different (Fig. 4A), i.e., in animals with similar infarct sizes, the group treated with Adeno-βARKct had lower EDP, suggesting that the presence of the βARKct reduced the degree of LV dysfunction in comparison to EV-treated animals. Thus, the hearts of infarcted rabbits treated with Adeno-βARKct do not appear to be progressing toward HF as rapidly as with EV and PBS treatment. By 20 days after surgery, the regression lines were not significantly different, as LV EDP gradually increased in the βARKct group, probably because of the gradual loss of the transgene (Fig. 4B). Previously in this model, 3 weeks after MI, rabbits were in overt HF as demonstrated by pleural effusions, ascites, and significantly depressed cardiac function as measured by echocardiography and cardiac catheterizations when compared with sham-operated control animals (13). In this study at day 20 after MI, although LV EDP is now elevated in all LCx-ligated groups including Adeno-βARKct-treated rabbits, there is a significant within-group reduction of LV EDP in response to Iso only in the sham and βARKct groups (Fig. 5A). In fact, βAR stimulation results in completely normalized EDP values when the βARKct is expressed in 20 day after MI rabbit hearts (Fig. 5A).

Figure 3.

LV EDP 10 days after LCx ligation and treatment with either PBS, 5 × 1011 tvp EV, or 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-βARKct. *, P < 0.001 vs. sham; †, P < 0.05 vs. lig + PBS and vs. lig + EV (one-way ANOVA with Newman–Keuls post-hoc analysis).

Figure 4.

Baseline EDP is plotted vs. infarct size for EV (n = 11; diamonds, dotted line) and Adeno-βARKct-treated (n = 11; squares, solid line) rabbits. (A) At day 10, the equations for the regression lines are y = 0.3617x −2.725, r = 0.81 for EV, and y = 0.1663x −0.6297, r = 0.68 for Adeno-βARKct; P < 0.005 for overall coincidence, indicating that the lines are significantly different. (B) At day 20, y = 0.1580x + 2.333, r = 0.57 for EV and y = 0.2719x −0.7664, r = 0.72 for Adeno-βARKct, and the lines are not significantly different (P = 0.50).

Figure 5.

Hemodynamic function 20 days after LCx ligation and treatment with either PBS, 5 × 1011 tvp EV or 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-βARKct. (A) LV EDP values at baseline (open bars) and in response to Iso (closed bars) (Iso, 0.1 μg/kg/min). *, P < 0.01 vs. baseline values (paired t test); †, P < 0.05 vs. Iso–EV (Student's t test). There was no significant response to Iso in the PBS or EV groups. (B) LV dP/dtmax values at baseline and in response to Iso in Adeno-βARKct-treated (diamonds, n = 11) compared with EV-treated (triangles, n = 11) infarcted rabbits. †, P < 0.05 (ANOVA with repeated measures); *, P < 0.01 for individual doses (ANOVA with Newman–Keuls post hoc analysis).

When βARK1 activity is inhibited up to 20 days after MI, cardiac contractility in rabbits, as measured by LV dP/dtmax, is significantly enhanced at baseline and in response to Iso compared with EV-treated MI rabbits (Fig. 5B). Table 2 contains hemodynamic measurements 20 days after MI in Adeno-βARKct and EV-treated rabbits. Baseline LV EDP was significantly elevated and did not respond to Iso in the EV-treated rabbits, whereas LV dP/dtmin trended lower in these compared with Adeno-βARKct-treated rabbits, which had values similar to sham-operated controls (data not shown).

Table 2.

In vivo hemodynamic measurements at baseline and after Iso stimulation of rabbits 20 days after treatment with 5 × 1011 tvp Adeno-βARKct or EV and LCx ligation

| Day 20—Adeno-βARKct

|

Day 20—Adeno-EV

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | Iso 0.1 | Iso 0.5 | Basal | Iso 0.1 | Iso 0.5 | |

| LVdP/dtmax, mmHg/sec* | 2,966 ± 211† | 4,582 ± 241‡ | 5,450 ± 253‡ | 2,413 ± 171 | 3,863 ± 227 | 4,672 ± 291 |

| LVdP/dtmin, mmHg/sec | −2,278 ± 99 | −2,450 ± 116 | −2527 ± 176 | −1,867 ± 145 | −2,180 ± 119 | −2,341 ± 143 |

| LVSP, mmHg | 70.5 ± 2.8 | 70.9 ± 2.4 | 74.8 ± 2.6 | 61.7 ± 2.7 | 65.5 ± 2 | 68.7 ± 2.3 |

| EDP, mmHg | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 9.5 ± 1.3 | 6.8 ± 1.9 | 6.8 ± 2.3 |

| HR, bpm | 192 ± 8 | 249 ± 8 | 268 ± 9 | 204 ± 6 | 254 ± 7 | 250 ± 8 |

*, P < 0.05 vs. EV for between-groups main effect (ANOVA with repeated measures); †, P < 0.01, and ‡, P < 0.001 vs. EV for specific dose (Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis). HR, bpm, heart rate, beats per minute. n = 11.

After in vivo assessment of cardiac function 20 days after MI, hearts were excised to examine infarct size and biochemical βAR signaling characteristics of noninfarcted myocardium. Infarct size was not statistically different between adenovirus groups [EV 37.8 ± 3.4% (n = 11) vs. βARKct; 32.6 ± 4.5% (n = 11), P = not significant]. βARKct mRNA expression was found in all hearts treated with Adeno-βARKct (20 days after MI), although expression was considerably less than that seen 7 days after gene delivery (data not shown). βAR signaling in the Adeno-βARKct-treated rabbits at 20 days after MI reflected the physiology, as some changes were starting to occur. For example, myocardial βARK1 expression in Adeno-βARKct-treated rabbits was slightly but not significantly increased (25%) over sham-operated controls at 20 days after MI. However, βAR density in the 20 days after MI rabbit hearts treated with Adeno-βARKct was still similar to that in sham-operated hearts [56.8 ± 2.7 fmol per milligram membrane protein (n = 5) vs. 60.5 ± 2.0 (n = 7), P = not significant].

Discussion

The data presented offer insights into the in vivo actions of βARK1 in the failing heart and demonstrate the potential power of a gene therapy approach for treating HF. Our results indicate that βARKct expression via in vivo intracoronary adenoviral-mediated gene delivery in the ischemic heart improves compromised cardiac function. Moreover, they demonstrate that preserving the integrity of the myocardial βAR system after MI can delay the development of HF. These findings do not support the generally accepted belief that desensitization and down-regulation of βARs in the failing heart protect the heart against chronic sympathetic stimulation. Rather they suggest that βAR signaling alterations seen after MI may actually be maladaptive and therefore may contribute to the pathogenesis of HF.

Biochemical analysis of rabbit myocardium as early as 3 days after LCx ligation reveals that βAR signaling abnormalities, including βAR down-regulation and decreased adenylyl cyclase activity, are present in concert with elevated levels of βARK1 before the development of hemodynamic HF. Myocardial gene delivery of βARKct at the time of MI prevented the up-regulation of βARK1 and the subsequent βAR signaling abnormalities described above. The prevention of these biochemical alterations in myocardial βAR signaling persisted for the 3-week duration of this study. The loss of βAR down-regulation in the Adeno-βARKct-treated MI rabbits is most likely because cardiac function is enhanced in these hearts and compensatory mechanisms (such as the sympathetic nervous system) are not activated, rather than reflecting any direct effect of the βARKct on βAR expression.

From our physiological data, it is clear that HF is significantly delayed in this model when βARK1 is inhibited acutely after MI. Moreover, 10 days after MI, rabbits that received Adeno-βARKct had normal heart function. In fact, cardiac function in the βARKct-expressing rabbits was enhanced 3 weeks after MI at a time when control MI-rabbits have significantly elevated EDP and decreased responsiveness to β-adrenergic agonists, characteristic features of HF. Thus, inhibition of βARK1 acutely after MI results in preserved cardiac signaling as well as systolic function and, importantly, the development of HF is delayed.

We have previously demonstrated the potential therapeutic usefulness of the βARKct in transgenic mouse models, where inhibition of myocardial βARK1 activity enhances in vivo cardiac performance (21–23). Crossbreeding of βARKct transgenic animals with a genetic mouse model of cardiomyopathy induced by ablation of the muscle LIM protein gene resulted in the complete prevention of HF in this model (23). We have also previously shown that the βAR signaling abnormalities present in failing cardiomyocytes isolated from rabbit hearts in HF could be reversed on adenoviral-mediated βARKct expression (24). Taken together, these studies, coupled with our current results, suggest that inhibition of cardiac βARK1 activity, either by gene transfer or by the development of a pharmacologic inhibitor, may represent a novel approach to the treatment of HF.

The conventional view of the role of sympathetic activation in HF is that the resultant elevated myocardial βARK1 levels and βAR desensitization in the dysfunctional heart are actually protective mechanisms. Abrogation of such compensatory mechanisms, it has been reasoned, would only worsen the physiologic deterioration caused by excess catecholamine stimulation. Indeed, the chronic use of β-agonists in HF is harmful (25). However, it should be emphasized that expression of the βARKct, as demonstrated in several of our studies, appears to result in a very different outcome than administering βAR agonists. First, administration of an oral β-agonist leads to further βAR down-regulation in the lymphocytes of patients with HF (26). In addition, βARK1 expression is increased after βAR stimulation (17). Therefore, the use of β-agonists in HF patients exacerbates disturbances in the myocardial βAR system, leading to further receptor down-regulation and increases in βARK1. In contrast, restoration of βAR signaling through gene delivery of the βARKct has a fundamentally opposite effect at a molecular level, i.e., it preserves the number of βARs and inhibits βARK1.

Because the actions of βARK1 in the heart are not limited to βARs (27), enhanced signaling through other GPCRs may be involved in the salutary effects of the βARKct. Moreover, given the recent evidence that β1- and β2ARs lead to qualitatively different patterns of signaling in the heart (28), the inhibition of βARK1 may influence signaling through these two βARs in a selective or specific manner. Such differential modulation of receptor signaling is a potentially important area for βARKct's action and will be examined in detail in future studies. A potential mechanism contributing to the effects of the βARKct may be the inhibition of the βγ-subunits of activated G proteins (Gβγ)–βARK1 interaction. This interaction not only promotes GPCR desensitization but also has recently been shown to trigger other novel signaling pathways such as the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades (29). The activation of the MAPK cascade by several GPCRs, including βARs, has been shown to proceed in parallel with the internalization of receptors induced by GRK phosphorylation (29). Thus, one speculation is that whereas inhibition of the Gβγ–βARK1 interaction enhances βAR-Gs signaling, thus supporting the contractile function of the heart, the same inhibitory actions might reduce activation of MAPKs, thereby preventing signaling that has the potential to lead to damaging consequences such as pathological hypertrophy and apoptosis.

It is interesting that βARK1 inhibition shares with β-blockade the potential to normalize or remodel signaling through the cardiac βAR system in HF. Moreover, both treatments lower cardiac GRK activity, enhance catecholamine sensitivity, and raise or preserve myocardial levels of βARs (17). Thus, it is possible that part of the salutary effects of β-blockers on the failing heart is because of their demonstrated ability to reduce expression of βARK1 in the heart. With the overwhelming positive data showing the beneficial effects of β-blockers in the treatment of HF (15, 16), it is reasonable to question whether the strategy of adding a βARK1 inhibitor adds anything novel to the therapeutic armamentarium. However, given the results of this study, it is apparent that β-antagonist therapy and βARK1 inhibition may in fact be complementary therapeutic modalities. For example, although treatment with β-blockers antagonizes the catecholamine toxicity associated with HF, βARK1 inhibition might act to preserve normal βAR-G protein coupling in times of need such as during exercise and periods of stress. Thus, there may be major differences between these two therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank K. Campbell, K. Shotwell, and K. Wilson for technical assistance throughout this study, Drs. John Maurice and Andrea Eckhart for assistance, and Dr. Howard Rockman for helpful suggestions. We also thank the Genzyme Corporation (Framingham, MA) for preparation and purification of Adeno-βARKct and EV. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants HL-16037 (R.J.L.), HL-59533 (W.J.K.), and HL-56205 (W.J.K.), and a Grant-in-Aid from the American Heart Association (W.J.K.). R.J.L. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations

- βAR

β-adrenergic receptor

- βARK1

βAR kinase

- GRK

G protein-coupled receptor kinase

- βARKct

inhibitory peptide of βARK1

- MI

myocardial infarction

- HF

heart failure

- LCx

left circumflex coronary artery

- EV

empty adenoviral vector

- LV

left ventricular

- EDP

end-diastolic pressure

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- Iso

isoproterenol

- tvp

total viral particles

Footnotes

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.090091197.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.090091197

References

- 1.Brodde O E. Pharmacol Ther. 1993;60:405–430. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90030-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leimbach W N, Wallin G, Victor R G, Aylward P E, Sundlof G, Mark A L. Circulation. 1986;73:913–919. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.5.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bristow M R, Ginsburg R, Minobe W, Cubicciotti R, Sageman W S, Lurie K, Billingham M E, Harrison D C, Stinson E B. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:205–211. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198207223070401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bristow M R, Minobe W, Raynolds M V, Port J D, Rasmussen R, Ray P E, Feldman A M. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2737–2745. doi: 10.1172/JCI116891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ungerer M, Bohm M, Elce J S, Erdmann E, Lohse M L. Circulation. 1993;87:454–463. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inglese J, Freedman N J, Koch W J, Lefkowitz R J. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23735–23738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson K M, Eckhart A D, Willette R N, Koch W J. Hypertension. 1999;33:402–407. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urasawa K, Yoshida I, Takagi C, Onozuka H, Mikami T, Kawaguchi H, Kitabatake A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;219:26–30. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho M C, Rapacciuolo A, Koch W J, Kobayashi Y, Jones L R, Rockman H A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(32):22251–22256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gros R, Benovic J L, Tan C M, Feldman R D. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2087–2093. doi: 10.1172/JCI119381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi D-J, Koch W J, Hunter J J, Rockman H A. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17223–17229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.17223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ungerer M, Kessebohm K, Kronsbein K, Lohse M J, Richardt G. Circ Res. 1996;79:455–460. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maurice J P, Shah A S, Kypson A P, Hata J A, White D C, Glower D D, Koch W J. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1853–H1860. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.6.H1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bristow M R. Lancet. 1998;352SI:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bristow M R. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:26L–40L. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Packer M, Bristow M R, Cohn J N, Colucci W S, Fowler M B, Gilbert E M, Shusterman N H. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1349–1355. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605233342101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iaccarino G, Tomhave E D, Lefkowitz R J, Koch W J. Circulation. 1998;98:1783–1789. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.17.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch W J, Inglese J, Stone W C, Lefkowitz R J. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8256–8260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hehir K M, Armentano D, Cardoza L M, Choquette T L, Berthelette P B, White G A, Couture L A, Everton M B, Keegan J, Martin J M, et al. J Virol. 1996;70:8459–8467. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8459-8467.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maurice J P, Hata J A, Shah A S, White D C, McDonald P H, Dolber P C, Wilson K H, Lefkowitz R J, Glower D D, Koch W J. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:21–29. doi: 10.1172/JCI6026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koch W J, Rockman H A, Samama P, Hamilton R A, Bond R A, Milano C A, Lefkowitz R J. Science. 1995;268:1350–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.7761854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akhter S A, Eckhart A D, Rockman H A, Shotwell K, Lefkowitz R J, Koch W J. Circulation. 1999;100:648–653. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.6.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rockman H A, Chien K R, Choi D-J, Iaccarino G, Hunter J J, Ross J, Jr, Lefkowitz R J, Koch W J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7000–7005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akhter S A, Skaer C A, Kypson A P, McDonald P H, Peppel K C, Glower D D, Lefkowitz R J, Koch W J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12100–12105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bristow M R, Lowes B D. Coron Artery Dis. 1994;5:112–118. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199402000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colucci W S, Alexander R W, Williams G H, Rude R E, Holman B L, Konstam M A, Wynne J, Mudge G H, Braunwald E. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:185–190. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198107233050402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iaccarino G, Lefkowitz R J, Koch W J. Proc Assoc Am Phys. 1999;111:399–405. doi: 10.1111/paa.1999.111.5.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lefkowitz R J, Rockman H A, Koch W J. Circulation. 2000;101:1634–1637. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.14.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luttrell L M, Ferguson S S, Daaka Y, Miller W E, Maudsley S, Della Rocca G J, Lin F, Kawakatsu H, Owada K, Luttrell D K, et al. Science. 1999;283:655–661. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]