Abstract

There is mounting evidence that estrogens act directly on the nervous system to affect the severity of pain. Estrogen receptors (ERs) are expressed by sensory neurons, and in trigeminal ganglia, 17β-estradiol can indirectly enhance nociception by stimulating expression and release of prolactin, which increases phosphorylation of the nociceptor transducer transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor 1 (TRPV1). Here, we show that 17β-estradiol acts directly on dorsal root ganglion (DRG) sensory neurons to reduce TRPV1 activation by capsaicin. Capsaicin-induced cobalt uptake and the maximum TRPV1 current induced by capsaicin were inhibited when isolated cultured DRGs neurons from adult female rats were exposed to 17β-estradiol (10–100 nm) overnight. There was no effect of 17β-estradiol on capsaicin potency, TRPV1 activation by protons (pH 6–4), and P2X currents induced by α,β-methylene-ATP. Diarylpropionitrile (ERβ agonist) also inhibited capsaicin-induced TRPV1 currents, whereas propylpyrazole triol (ERα agonist) and 17α-estradiol (inactive analog) were inactive, and 17β-estradiol conjugated to BSA (membrane-impermeable agonist) caused a small increase. TRPV1 inhibition was antagonized by tamoxifen (1 μm), but ICI182870 (10 μm) was a potent agonist and mimicked 17β-estradiol. We conclude that TRPV1 in DRG sensory neurons can be inhibited by a nonclassical estrogen-signalling pathway that is downstream of intracellular ERβ. This affects the vanilloid binding site targeted by capsaicin but not the TRPV1 activation site targeted by protons. These actions could curtail the nociceptive transducer functions of TRPV1 and limit chemically induced nociceptor sensitization during inflammation. They are consistent with clinical reports that female pelvic pain can increase after reductions in circulating estrogens.

THE SEVERITY OF pain is influenced by the effects of circulating gonadal steroids on the central and peripheral nervous system (1). These effects are complex, and it has proven difficult to study them by measuring spontaneous or experimental pain in clinical and in vivo animal studies. This could be due to the slow time course of the classical genomic effects of estrogen signaling, and the multiplicity of neuronal and nonneuronal downstream targets affected by circulating estrogens. As a result, we cannot yet unequivocally classify estrogens as “pro-nociceptive” or “anti-nociceptive,” and it is possible that both kinds of effect may occur in different parts of the nervous system at different times. For example, mice develop robust mechanical allodynia and hyperalgesia, and show increased visceral sensitivity when circulating estrogens are reduced after an ovariectomy (2). Conversely, prolonged elevation of estrogen levels during pregnancy is antinociceptive in humans (3,4). In contrast, studies of trigeminal sensory ganglia (5) have reported evidence of pronociceptive effects that increase nociceptor excitability by reducing action potential thresholds, increasing spontaneous firing, and facilitating transient receptor potential cation channels [subfamily V, member 1; transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor 1 (TRPV1)] (6).

Clinical reports suggest that many types of pelvic pain, such as interstitial cystitis, are influenced by hormonal status (1,7). Anatomical studies suggest that pelvic pain could be influenced by direct estrogenic modulation of nociceptors in lumbosacral dorsal root ganglia (DRG) because many of these neurons express the estrogen receptors (ERs): ERα and ΕRβ (8,9,10). Relatively little is known about ER signaling in DRG nociceptors, but 17β-estradiol can rapidly inhibit (<5 min) ATP-induced increases in intracellular calcium (11) and inhibit calcium currents (12) in isolated DRG neurons. Our group also has reported that longer (30 min) exposure to 17β-estradiol can activate ERK1/2 and increase downstream signaling by the constitutive transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein (13). In this study we report evidence that prolonged exposure of DRG neurons to 17β-estradiol can inhibit activation of a major chemical/thermal nociceptive transducer, the cation channel TRPV1 (14,15).

Materials and Methods

Neuronal cultures

Procedures were performed according to the guidelines specified by the requirements of the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes, and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Sydney. The study used 63 adult (6–8 wk) female Sprague Dawley rats supplied by the Gore Hill Animal Laboratory (Sydney, Australia). Rats were heavily anesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone (80 mg/kg), then decapitated. Lumbar 16 and sacral 1 DRG were quickly removed bilaterally under a dissecting microscope, and transferred into modified Tyrode’s solution containing (mm) NaCl 130, NaHCO3 20, KCl 3, CaCl2 4, MgCl2 1, HEPES 10, glucose 1,2 and antibiotic/antimycotic solution. Neurons were then dispersed and cultured as described previously (13). DRGs were collected in collagenase (Type I; Worthington Biochemical Corp., West Chester, PA) and trypsin (0.25%; Invitrogen, Mt. Waverley, Australia) at 37 C for 1 h. DRGs were then washed, triturated, mixed with BSA (15%; Sigma-Aldrich, Castle Hill, Australia), and centrifuged at 900 rpm for 10 min to remove myelin and debris. The pellet was resuspended with Neurobasal A and B27 (Invitrogen) and neurons plated onto 22-mm diameter glass coverslips, previously coated with polyornithine (Sigma-Aldrich) and laminin (Invitrogen). No serum, growth factors, or other additives were included in the Neurobasal A/B27 media, which do not contain estrogens (16). The neurons were maintained at 37 C in a humidified atmosphere containing 95%/5% air/CO2 for 2 d before use.

Cobalt uptake

TRPV1 activation was measured in populations of neurons by treating DRG cultures with capsaicin in an extracellular cobalt solution, and measuring precipitated cobalt in fixed cells with densitometry (17). Briefly, coverslips were exposed for 25 min to capsaicin or the substance of interest in a calcium-free buffer containing (mm) KCl 5, MgCl2 2, d-glucose 12, HEPES 10, sucrose 137, NaCl 5.8 (pH adjusted to 7.4), and containing 10 mm cobalt. The cobalt was precipitated with 1.2% ammonium sulfide, and neurons were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for analysis of OD. For each coverslip, was measured in a minimum of 100 randomly selected neurons, and the mean for the population calculated. Control coverslips (vehicle treatment) were included in each experiment.

Electrophysiological recording

Patch clamp recordings were made using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, now Molecular Devices, Union City, CA) and standard whole cell techniques. Electrodes were pulled from 1.5-mm internal diameter capillary glass (A-M Systems Inc., Carlsborg, WA) using a vertical puller (PP-830; Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) and had resistances from 2–5 mΩ (3.67 ± 0.04 mΩ, n = 164) when filled with internal solution. Membrane current commands were controlled by an ITC-16 Interface (InstruTech Corp., Port Washington, NY). Data acquisition, storage, and analysis were performed using AxoGraph X software (Axograph Scientific, Sydney, Australia) run on Mac OS × 10.3.9 (Macintosh, Apple Computer, Inc., Cupertino, CA). Signals were low-pass filtered at 5 kHz, with no compensation for series resistance. The average series resistance and capacitance read from the amplifier were 7.39 ± 0.15 mΩ and 35 ± 1.1 pF (n = 164), respectively. All recordings were performed at room temperature (20–22 C). For patch clamp recording, the culture medium was replaced with normal external solution containing (mm) NaCl 140, KCl 4, HEPES 10, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, glucose 10 (pH adjusted to 7.4), with NaOH and osmolarity adjusted to 320 mOsmol. For voltage clamp, the internal solution contained (mm) Cs-methane sulfonate 110, HEPES 10, EGTA 9, phosphocreatine di-Tris 14, Mg-ATP 5 and GTP-Tris salt 0.3 (pH adjusted to 7.3), with CsOH and osmolarity adjusted to 315 mOsm. Drugs were applied during recordings by local perfusion with a fast-switch system (SF-77B; Warner Instrument Corp., Hamden, CTT) in which up to six barrels were connected to a manifold inserted into a common outlet glass tube (tip diameter of 0.6 mm) placed about 200 μm from the cell of interest. Solutions were delivered by gravity flow from independent reservoirs. One barrel was used to apply drug-free solution to enable rapid termination of drug application. Solution exchange controlled by computer was complete in 20 ms.

Western blotting

TRPV1 protein was quantified in cultured isolated DRGs neurons exposed to estradiol (10 and 100 nm) or vehicle in culture (24 h culture then 24 h treatment). Each culture was performed using tissues from a different animal, and each treatment was performed in triplicate for each animal (n = 3 rats). Each culture had its own internal control. Protein levels in DRG extracts were assessed in two replicate samples for each using animal methods modified from Purves-Tyson and Keast (13). Samples were not stored at any stage of the procedure, i.e. Western blotting studies were performed on the same day as protein extraction. Chilled lysis buffer containing T-PER protein extraction reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL), a standard protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete Mini; Roche, Castle Hill, New South Wales, Australia) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (PhosSTOP; Roche), was added to each well of the culture, and cells were removed by scraping, collected, then briefly sonicated. After centrifugation, aliquots of supernatant containing approximately 10 μg protein were mixed with loading buffer loaded on 10% SDS-PAGE, electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, and blocked with 5% nonfat milk solution for 1 h at room temperature. Gels were divided into two sections to allow separate processing for TRPV1 and b-tubulin. The membrane sections (>75 kDa) were then washed and incubated overnight at 4 C with a primary antibody against the N terminus of TRPV1 (host rabbit; Neuromics, Edina, MN; RA10110, 1:1,000). After washing, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit IgG (1:50,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was visualized using a chemiluminescent reagent (LumiGLO; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA). The other half-membrane sections (<75 kDa) were probed for β-tubulin (1:10,000, host mouse; Sigma-Aldrich) using antimouse IgG (1:50,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), and results were expressed related to β-tubulin levels in each lane. A band was observed at approximately 97 kDa for TRPV1 and approximately 50 kDa for β-tubulin. Band densities were converted to numerical values using Quantity One (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA), subtracting background values from an area of gel immediately adjacent to the stained band. Data have been expressed as the ratio of TRPV1 to β-tubulin for each sample.

Experimental design

DRG neurons isolated from each rat were split, plated onto multiple dishes, and cultured overnight. In most of the experiments, drugs were first applied on the following day, when neurons had been in culture approximately 24 h. Dishes from the block of dishes obtained from one rat were randomly allocated to each of the drug treatments, including a vehicle control, required for a single experiment. Cultures were then treated with drug overnight, and cobalt uptake measurements or electrophysiological recordings were performed on the following day when the neurons had been in culture for approximately 48 h.

In every experiment this procedure was replicated using blocks of culture dishes obtained from different rats. Replicates for a single experiment were normally obtained from cultures prepared on consecutive working days. This approach allowed us to control systematic variance between cultures, which was reflected by differences in control experiments measuring the density of the current induced by capsaicin. These differences in maximum current density did not appear to alter the effect of 17β-estradiol (see Figs. 3A and 5, A and B), which consistently reduced the average maxima to around 35% of the control value.

Figure 3.

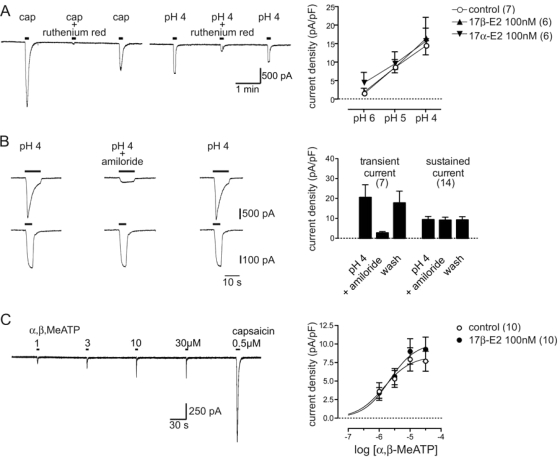

Long overnight exposure to 17β-estradiol had no effect on TRPV1 activation by protons or P2X currents activated by α,β,MeATP. A–C, Representative whole-cell patch clamp recording of currents in control DRG neurons, and plots of mean current density (± sem) obtained by normalizing the peak current against the membrane capacitance. External solution with 0.01% dimethylsulfoxide was used as a vehicle control. A, Inhibition of capsaicin- and sustained proton-activated (pH 4) currents by ruthenium red (10 μm). ANOVA showed that sustained currents induced by rapid acidification to pH 6, 5, or 4 were not affected by 17β-estradiol or 17α-estradiol (P > 0.05 vs. control; n = 7 per treatment). B, Representative recordings of proton-activated (pH 4) currents with (top trace) and without (bottom trace) an initial transient component. Amiloride (100 μm) reduced proton-activated currents with a transient component by 81 ± 4% (n = 7), whereas sustained currents with no transient component were reduced by 3 ± 2% (n = 14). Plots of group data illustrate this effect of amiloride on the mean current density of transient and sustained proton-activated currents. C, Global fitting analysis showed that the α,β-MeATP concentration-response relationship was not affected by 17β-estradiol (P = 0.51 vs. control). Data are mean ± sem; n values are cited in each legend.

Figure 5.

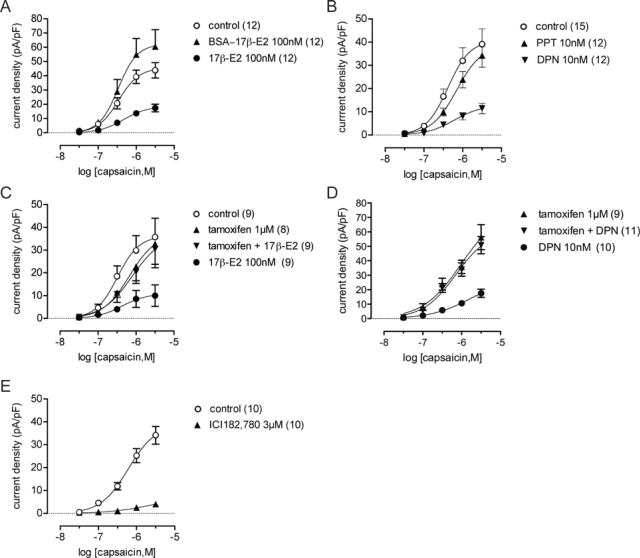

Capsaicin currents were reduced by intracellular ERβ signaling. A–E, Plots of capsaicin concentration-response relationships after single or combination overnight treatments with ER agonists and antagonists, or a vehicle control (0.01% dimethylsulfoxide in external solution). A, Global fitting analysis showed that a small increase in the maximum (P < 0.01) was induced by membrane impermeable BSA conjugated 17β-estradiol without any effect on the EC50. B, Global fitting analysis showed inhibition by the ERβ agonist DPN (P < 0.01 vs. control) but no effect of the ERα agonist PPT. C and D, Plots showing complete antagonism of the effect of 17β-estradiol and DPN by tamoxifen. E, Plot showing inhibition by ICI 182,780 (P < 0.01 vs. control). Data are mean ± sem; n values are cited in each legend.

In experiments that tested the effect of brief drug exposure, cobalt uptake measurements and electrophysiological recordings were again performed on neurons that had been in culture for approximately 48 h. Cobalt uptake was measured in cultures pretreated with 17β-estradiol (10 nm) or vehicle for 30 min. The effect of acute steroid exposure on the amplitude of capsaicin-induced currents was measured by perfusing cultures with 17β-estradiol or 17α-estradiol (both 10 nm) during electrophysiological recordings. Because no consistent acute effect of 17β-estradiol was detected by these experiments, we did not test for acute effects of other drugs used in this study.

Data analysis

Concentration-response data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism for Mac OS X version 4.0c software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Concentration-response data for each treatment were fitted to a three-parameter logistical function to obtain estimates of the maximum response, LOGEC50, and Hill slope. Nested global curve fitting was used to test for treatment effects within a series of matched experiments, and to then test if the maximum response and LOGEC50 parameter were both affected by the treatment. All other statistical comparisons were performed with SPSS for Mac OS X version 13 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Reagents

Amiloride, capsaicin, 17α-estradiol, 17β-estradiol, BSA-estradiol, LY290042, and α,β-methylene ATP (α,β-MeATP) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Diarylpropionitrile (DPN), propylpyrazole triol (PPT), and tamoxifen were obtained from Tocris (Ellisville, MO), and ICI 182780 was a gift from AstraZeneca (North Ryde, Australia). Stock solution of α,β-MeATP was prepared in deionized water and stored frozen. Other stocks (10 mm) were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide. All drugs were then diluted (0.1% or less) to the final concentration in tissue culture medium (for cell treatments before electrophysiology or cobalt reaction) or extracellular bathing solution (for treatments applied during recording).

Results

17β-Estradiol inhibition of capsaicin-induced cobalt uptake

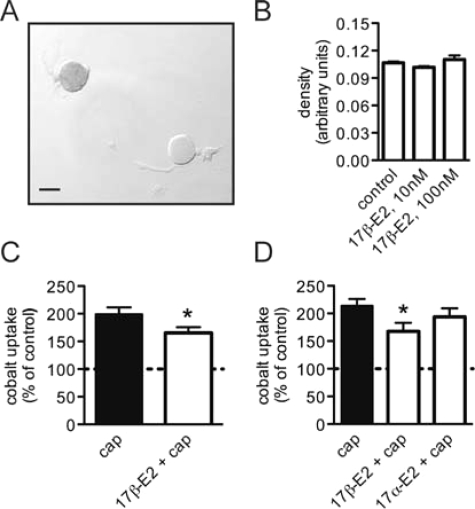

To determine whether 17β-estradiol could affect activation of TRPV1, capsaicin-induced cobalt uptake was measured by densitometry in dissociated lumbosacral (L6, S1) DRGs neurons from adult female rats (Fig. 1A). The neurons were cultured in serum free media (Neurobasal A) for 24 h and then treated overnight with 17β-estradiol before being stimulated with capsaicin (500 nm, 30 min). Cobalt uptake was not detectable in cultures that were not stimulated with capsaicin, and overnight treatment with 17β-estradiol (10 and 100 nm) had no effect on baseline OD measurements (Fig. 1B). A small but significant reduction in capsaicin-induced cobalt uptake was detected (Fig. 1C) after overnight treatment with 17β-estradiol (10 nm), and this inhibition was steroid specific because 17α-estradiol had no effect (Fig. 1D). This stereoisomer of 17β-estradiol is considered to be physiologically inactive at ERα, ERβ, and the G protein-coupled ER GPR30 (18). Capsaicin-induced cobalt uptake was not inhibited by rapid 17β-estradiol signaling when the period of steroid exposure was reduced to 30 min (paired t test: P = 0.84; n = 3).

Figure 1.

17β-Estradiol reduced capsaicin induced cobalt uptake. A, Black cobalt precipitant was measured by densitometry from images of fixed lumbosacral DRG neurons that were maintained in culture for 2 d and treated with capsaicin (500 nm, 30 min) in the presence of 10 mm extracellular cobalt. Scale bar, 25 μm. B, Density measurements from cultures that were not stimulated capsaicin, showed no cobalt uptake induced by 17β-estradiol. ANOVA: P = 0.30 (n = 3). Culture medium containing 0.01% dimethylsulfoxide was used as the control. C, Capsaicin-stimulated (cap) cobalt uptake was reduced after overnight treatment with 17β-estradiol (10 nm). *Paired t test: P = 0.002 (n = 9). D, Inhibition of capsaicin-stimulated cobalt uptake by 17β-estradiol was not mimicked by the stereoisomer 17α-estradiol (10 nm). *Paired t test, Bonferroni correction: P < 0.01 vs. control (n = 4). Data are mean ± sem.

17β-Estradiol inhibition of capsaicin-induced TRPV1 currents

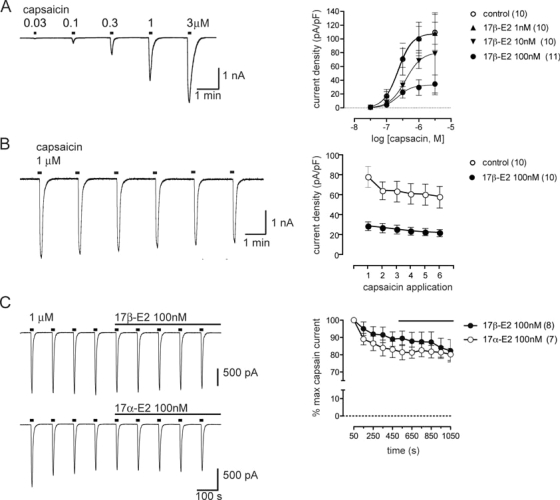

To determine the effect of 17β-estradiol on the capsaicin concentration-response relationship, electrophysiological voltage-clamp recordings were used to measure the peak amplitude of TRPV1 currents induced by brief (5 s) applications of capsaicin at different concentrations (Fig. 2A). The current density was estimated from these values by using the cell capacitance as a measure of the plasma membrane surface area. 17β-Estradiol (100 nm) applied overnight before electrophysiological recording reduced the average maxima to 33% of the control value but did not significantly affect the EC50 parameter (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

TRPV1 currents activated by capsaicin are reduced by long but not short exposure to 17β-estradiol. A-B, Representative whole-cell patch clamp recording of currents in control DRG neurons, and plots of mean data (± sem) showing the effect of overnight culture in different concentrations of 17β-estradiol vs. a vehicle control (0.01% dimethylsulfoxide in external solution). Plots show the mean current density obtained by normalizing the peak current against the membrane capacitance. A, Global fitting analysis showed that the mean maximum response to capsaicin was reduced by 17β-estradiol (10 and 100 nm: P < 0.05 vs. control), but there was no change in the EC50 parameter (all concentrations: P > 0.05 vs. control). B, Limited desensitization of currents activated by repeated application of capsaicin (1 μm, 5 sec applications every 100 sec) in a control culture. Plots of group data showed that 17β-estradiol did not facilitate desensitization. C, Representative whole-cell patch clamp recording of currents in control DRG neurons, and plots of mean data (± sem) showing that TRPV1 currents were not affected by 17β- or 17α-estradiol when applied during the recording. Data are mean ± sem; n values are cited in each legend.

Because only the maxima of the capsaicin concentration-response relationship was reduced, this suggested that the steroid reduced the density of functional TRPV1 channels in the plasma membrane without affecting the sensitivity of channel activation by capsaicin. The apparent reduction in channel density was not associated with an increase in plasma membrane surface area induced by 17β-estradiol (1, 10, and 100 nm) because we did not detect an increase in cell capacitance (ANOVA: F3,37 = 0.36; P = 0.78) or mean soma diameter of neurons used for recordings (ANOVA: F3,37 = 1.11; P = 0.36). The capsaicin concentration effect relationship was not affected when 17β-estradiol (100 nm) was applied for only 1 h on the day before electrophysiological recording (data not shown).

To determine whether 17β-estradiol enhanced desensitization of TRPV1, we then tested repeated applications of a maximally effective concentration of capsaicin. Under our recording conditions, repeated application of capsaicin in control cultures did not significantly desensitize TRPV1 (Fig. 2B). Estrogen-treated cultures also failed to show significant TRPV1 desensitization. This suggested that the steroid effect on the concentration-response curve was not due to increased desensitization induced by repeated application of capsaicin.

We also determined that neither 17β- nor 17α-estradiol had a rapid effect on capsaicin-induced currents (Fig. 2C). The steroids were applied for a 10-min period after the amplitude of currents induced with repeated applications of capsaicin (1 μm every 100 sec) had stabilized.

17β-Estradiol does not inhibit acid-induced TRPV1 currents

We next determined whether 17β-estradiol could affect activation of TRPV1 by protons, which was measured by exposing neurons to rapid acidification (pH 6, 5, and 4). In sensory neurons, acidification to pH 6 or lower can activate transient acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) currents, whereas acidification to pH 5 and 4 can activate TRPV1 (19). We found that currents activated by acidification to pH 4 were reduced by 74 ± 4% (n = 12) (Fig. 3A) when neurons were exposed to a concentration of the nonselective TRPV1 ion channel blocker ruthenium red (10 μm) that inhibited capsaicin currents by 93 ± 2% (n = 7). Furthermore, in most neurons the currents induced by acidification were sustained and were not significantly affected by amiloride (t test: P > 0.05 vs. control pH 4 current; n = 17) (Fig. 3B), which blocks ASIC currents. In contrast, when our recordings in a small number of neurons revealed an early transient component consistent with coactivation of an ASIC current (cf. 18), amiloride reduced the current induced by acidification in these cells by 81 ± 4% (t test: P < 0.001 vs. control pH 4 current; n = 7) (Fig. 3B). These data suggested that a majority of the sustained inward currents induced by acidification in our recordings were carried by TRPV1, but we found that these currents were not significantly affected by 17β-estradiol treatment (Fig. 3A). This suggested that steroid signaling selectively affected functioning of the vanilloid-binding site used by capsaicin to activate TRPV1 but did not affect the proton-binding site.

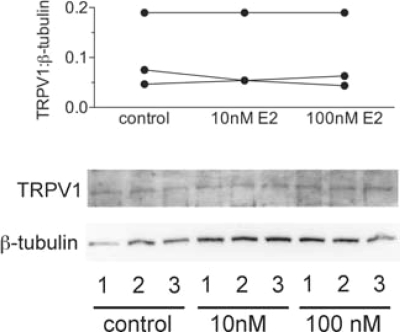

If TRPV1 can be activated by protons after overnight treatment with 17β-estradiol treatment, this suggests that there is no net change in the density of TRPV1 channels in the plasma membrane. We also failed to measure any change when total TRPV1 protein expression was measured by Western blotting analysis (Fig. 4). Bands of 95 kDa corresponding to TRPV1 were present in extracts from control and 17β-estradiol treated cultured neurons isolated from three rats, but the steroid had no effect on protein levels.

Figure 4.

Western blots (top) showing TRPV1 and β-tubulin protein expression in total cell lysates of DRG cultures treated with 0 (control), 10, or 100 nm 17β-estradiol. Shown are data from three replicate experiments using DRGs isolated from three rats identified by the numbers in each lane. Plots of the TRPV1 to β-tubulin band density ratios (bottom) show no effect of 17β-estradiol.

17β-Estradiol does not inhibit ATP currents

P2X3 receptors are expressed almost exclusively in small nociceptive neurons, and in DRG neurons, form homomers and P2X2/3 multimers that are transducers for nociceptive stimulation by extracellular ATP (20,21,22,23). In the adult rat, P2X3 is coexpressed by a majority of capsaicin-sensitive lumbar DRG neurons that express TRPV1 (24) and in approximately 90% lumbosacral bladder-projecting DRG neurons (25). To determine the effect of 17β-estradiol on the ATP concentration-response relationship, we measured the peak amplitude of currents induced by brief applications of α,β-MeATP at different concentrations (Fig. 3B). 17β-Estradiol (100 nm) did not significantly affect the P2X currents.

17β-Estradiol does not activate extracellular ERs

17β-Estradiol conjugated to BSA cannot penetrate the cell membrane and did not inhibit the capsaicin current but, instead, caused a small increase in the maximum response of the capsaicin current (Fig. 5A). This failure to impair TRPV1 signaling indicated that 17β-estradiol effects on this channel are likely to be mediated by an intracellular receptor. We propose that this involves ERβ because capsaicin currents were significantly reduced by DPN (10 nm), considered to be a ERβ selective agonist, but were not affected by PPT (10 nm), considered to be a ERα selective agonist (26) (Fig. 5B). Like 17β-estradiol, DPN reduced the average maxima by 69% without significantly affecting the EC50 parameter. This result obtained by electrophysiological recordings was also confirmed by measuring capsaicin-induced cobalt uptake (211 ± 22% of control, n = 3), which was significantly reduced by DPN (10 nm; 148 ± 21%) but not PPT (10 nm; 170 ± 13%) (Tukey’s test: P < 0.05 vs. control).

Pharmacology of TRPV1 inhibition by ERs

We then tested two widely used ER antagonists that differ in their mechanisms of action (27). Tamoxifen (1 μm), considered a nonselective antagonist of ERα and ERβ, blocked inhibition of capsaicin currents by 17β-estradiol (Fig. 5C) and DPN (Fig. 5D). Tamoxifen itself had no direct effect on capsaicin currents. We also tested another widely used nonselective antagonist of intracellular ER’s, ICI 182,780 (3 μm). This showed agonist activity and mimicked the effect of 17β-estradiol by reducing capsaicin-induced currents (Fig. 5E). In contrast, ICI 182,780 (3 μm) had no effect on P2X currents activated by α,β-MeATP (P > 0.05; n = 7).

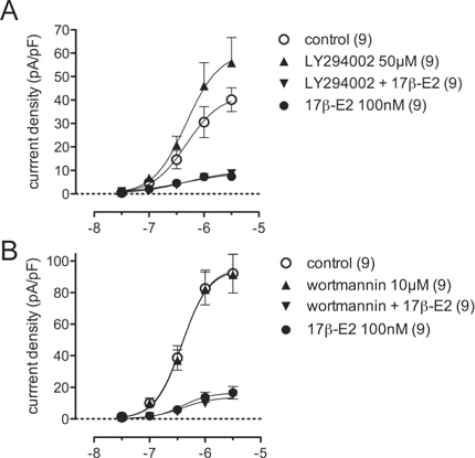

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling, which modulates TRPV1 (see Discussion) and can be activated by 17β-estradiol (28,29), did not appear to be involved in 17β-estradiol-induced inhibition of capsaicin-currents. We found that blocking PI3K signaling (Fig. 6) with LY294002 (50 μm) or wortmannin (10 μm) had no effect on steroid inhibition of TRPV1 (P = 0.17 and P = 0.78, respectively). However, LY294002 alone also had an effect on the capsaicin concentration-response relationship (P = 0.014).

Figure 6.

17β-Estradiol signaling was unaffected by inhibition of PI3K. Plots of capsaicin concentration-response relationships comparing control (0.01% dimethylsulfoxide in external solution), 17β-estradiol, and the PI3K inhibitors, LY294002 (A) or, wortmannin (B) applied alone or with 17β-estradiol. Data are mean ± sem; n values are cited in each legend.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that prolonged exposure to 17β-estradiol had a profound, highly specific “anti-nociceptive” effect on adult lumbosacral nociceptor neurons, by reducing the TRPV1 response to capsaicin but not affecting the TRPV1 response to protons or the response to ATP. Our results suggest that this is mediated by a nonclassical estrogen-signaling pathway involving intracellular ERβ. We have identified a novel endogenous mechanism to cause a direct, selective, and long-lasting inhibition of a key component of TRPV1 signaling. This analgesic property of estrogens could limit the activation or sensitization of the multifunctional nociceptive transducer, TRPV1, by endogenous ligands during inflammation and tissue damage. This may provide a therapeutic target to modulate pelvic pain.

Prolonged ER signaling inhibits TRPV1 activation by capsaicin in DRGs nociceptors

The evidence from our experiments suggested that 17β-estradiol prevented capsaicin from activating TRPV1 channels because the maximum current was reduced without any effect on the EC50 parameter that would have indicated a shift in pharmacological sensitivity. Because we only recorded from neurons exhibiting a response to capsaicin, we may have underestimated the inhibitory action of 17β-estradiol if some neurons failed to respond to capsaicin after estrogen treatment. The robust nature of this steroid effect on capsaicin-induced currents is also indicated by the fact that it could be measured reliably without controlling for the stage of the estrous cycle. By drawing parallels with the clinical literature, this could contribute significantly to between-subject experimental variance in our measurements.

Acute treatment with nerve growth factor has an opposite effect on TRPV1 in mouse DRG neurons (30), i.e. it increases the maximum capsaicin current without affecting the EC50 parameter, by causing intracellular TRPV1 to be inserted into the cell membrane (30,31,32,33). However, estrogen stimulation of endocytosis and a net loss of TRPV1 from the cell membrane cannot explain our result because TRPV1 activation by protons was not affected. This result provided evidence that there was no net change in functional TRPV1 channels in the plasma membrane. We also could not detect any change in total TRPV1 protein expression by Western blotting analysis. These data suggest that 17β-estradiol causes a novel posttranslational modification of TRPV1 channels that prevents functional channels in the membrane from being activated by capsaicin.

Evidence that TRPV1 inhibition is downstream of nonclassical intracellular ERβ signaling

Our data suggest that the TRPV1 response to capsaicin was most likely inhibited by ERβ signaling from an intracellular site. A caveat is that pharmacological identification of the receptor subtype was made using agonists selective for ERβ (DPN) and ERα (PPT) because to our knowledge, no subtype selective ER antagonists are currently available. TRPV1 did not appear to be inhibited by a membrane-initiated steroid mechanism because cell-impermeable BSA-17β-estradiol did not mimic the inhibitory action of 17β-estradiol. ERα, ERβ, and the estrogen-sensitive G protein-coupled receptor, GPR30, can all initiate estrogenic signaling from the plasma membrane of neurons (18,29,34,35). In contrast to transcriptional regulation by ERs, these pathways induce rapid and often transient signaling that occurs within seconds to minutes of receptor activation. In our experiment it is possible that such a mechanism could account for the small increase in the maxima of the capsaicin current caused by BSA-17β-estradiol. However, we were unable to detect any rapid effect of 17β-estradiol on cobalt uptake when cultures were exposed to 17β-estradiol for 30 min. Nor did 17β-estradiol have any effect on capsaicin-induced currents when applied during the recording. In contrast, inhibition of the TRPV1 response to capsaicin by 17β-estradiol was mimicked by cell-permeable agonists selective for ERβ (DPN) but not ERα (PPT) (26). Furthermore, the effects of 17β-estradiol and DPN were blocked by the selective estrogen modulator tamoxifen (34,35,36).

Our experiments using ICI 182,780 and tamoxifen provided an important insight into the possible mechanism by which 17β-estradiol inhibited capsaicin responses. In our studies, tamoxifen blocked the 17β-estradiol effects, but ICI 182,780 behaved as an ER agonist, being as effective as 17β-estradiol at inhibiting the TRPV1 response to capsaicin. ICI 182,780 is a “pure” steroidal antiestrogen that blocks the “classical” signaling of ERs, i.e. interaction of ERs with estrogen-responsive genes containing estrogen response elements; ICI 182,780 does not show partial agonism at these sites (34,35,36). ICI 182,780 also completely blocks nongenomic actions of estrogen signaling by ERs and is unable to exert nongenomic agonist actions through ERs (27). The agonist effect of ICI 182,780 argues against 17β-estradiol signaling via a classical nuclear mechanism in our experiments. We propose that 17β-estradiol impairs capsaicin gating of TRPV1 by a nonclassical nuclear mechanism involving association of ERs with transcription factors such as the activator protein-1, specificity protein-1, and signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 transcription factors because when ERs are tethered to these factors, ICI 182,780 shows agonist activity (27). ICI 182,780 has also induced an association between ERβ and nuclear factor NF-κB (37). The agonist effect of ICI 182,780 could also be consistent with GPR30 signaling (38,39), which recent evidence shows can be initiated from intracellular compartments (40). However, our findings are not consistent with reports that tamoxifen is a GPR30 agonist (38,39,41,42,43,44), and we are not aware of evidence that DPN can activate GPR30.

Potential significance of estrogen-induced reduction of capsaicin sensitivity in DRGs nociceptors

Numerous studies have described mechanisms by which TRPV1 is sensitized, such as after inflammation (14,15). This can lead to heat hyperalgesia, triggering pain at normal body temperature (45,46). Although a number of mechanisms have been proposed to inhibit sensitized TRPV1 channels, our study has revealed a novel inhibition of the capsaicin gating of TRPV1 in the absence of prior sensitization. Until recently, TRPV1 was thought to be tonically inhibited by phosphatidylinositol bis-phosphate (PIP2) (47), but there is now a growing consensus that PIP2 may actually potentiate TRPV1 (30,31,33). There is also evidence that PI3K, which promotes PIP2 hydrolysis, can associate with TRPV1 by direct protein-protein interactions (30). Because PI3K signaling can be activated by 17β-estradiol (28,29), we examined the possible involvement of this pathway but found that neither LY294002 nor wortmannin affected the inhibitory effect of the steroid on the capsaicin concentration-effect curve.

The reduced TRPV1 function we observed in estrogen-treated DRG neurons differs markedly from the effects that 17β-estradiol has on the trigeminal sensory system. Estrogen replacement (15–18 d) in ovariectomized rats increases excitability of acutely dissociated trigeminal neurons by lowering action potential thresholds and inducing spontaneous activity (5). Cultured trigeminal neurons isolated from ovariectomized rats administered daily estrogen injections for 10 d also show increased pharmacological sensitivity of TRPV1 to capsaicin (6). This has been attributed to a “classical” genomic effect of the steroid that is indirectly mediated by transcriptional up-regulation of prolactin in TRPV1-expressing neurons. This increases prolactin release after neuronal activity and facilitates prolactin autoreceptor signaling that in turn phosphorylates TRPV1 channels and increases sensitivity to capsaicin. Although these results suggest that 17β-estradiol may not reduce TRPV1 responses to capsaicin in trigeminal ganglia sensory neurons, this possibility cannot be completely excluded because it was not addressed experimentally by Diogenes et al. (6). Regardless, the strong possibility remains that estrogens have distinct actions on trigeminal and DRG sensory neurons, which could in turn relate to different functions of estrogen signaling on the trigeminal and pelvic somatosensory nociceptive systems. It remains to be established if estrogen can affect neurons in DRGs that do not innervate reproductive organs.

Our results suggest the possibility that ERβ agonists, or possibly even structural analogs of ICI 182,780, could have efficacy for reducing heat hyperalgesia, neurogenic inflammation, or other pain conditions affected by chemical activation of TRPV1. A very recent study has reported attenuation of formalin-induced pain behaviors and activation of fos in the spinal cord in ERβ knockout mice (48), which is highly consistent with our results on isolated nociceptors. In addition, the selective ERβ agonist ERB-041 attenuates prostaglandin E2- or capsaicin-induced thermal hyperalgesia measured by the immersion tail-flick assay in rats and chemically induced (carrageenan) paw edema, and thermal hyperalgesia measured by radiant heat using the Hargreaves method (49). However, in contrast to the present in vitro study, these in vivo actions of ERB-041 were detected within 60–100 min drug administration and were fully blocked by ICI 182,780, which had no effect on prostaglandin E2-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Moreover, the study was performed in male rats, and the effects of ERB-041 were studied after chemically induced inflammation, which sensitizes TRPV1. ICI 182,780 has also attenuated mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia after intrathecal administration (50). These authors attributed this to the block of progesterone signaling, but intriguingly this was on the basis that coadministration of estrogen enhanced the nociceptive effect of ICI 182,780. This evidence and the results of the present study suggest that the effects of 17β-estradiol and ICI 182,780 on the nociceptor terminals in the dorsal horn should be investigated. ERβ-deficient mice have also developed a bladder phenotype that resembles human interstitial cystitis (51). It was suggested that this resulted from hyperactivity of T cells infiltrating and damaging the bladder urothelium, but it is possible that changes in neuroimmune modulation (52) by ERβ-expressing sensory nerve terminals could contribute to this pathology. Our results would be consistent with 17β-estradiol limiting neurogenic inflammation in the bladder wall via TRPV1.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1DK069351-03 and National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellowship 358709 (to J.R.K.), and Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists Grant 05/019 (to P.B.O.).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online July 10, 2008

Abbreviations: ASIC, Acid-sensing ion channel; DPN, diarylpropionitrile; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; ER, estrogen receptor; α,β-MeATP, α,β-methylene ATP; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate; PPT, propylpyrazole triol; TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor 1.

References

- Holdcroft A, Berkley KJ 2006 Sex and gender differences in pain and its relief. In: Wall PD, McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, eds. Wall and Melzack’s textbook of pain. 5th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1181–1197 [Google Scholar]

- Sanoja R, Cervero F 2005 Estrogen-dependent abdominal hyperalgesia induced by ovariectomy in adult mice: a model of functional abdominal pain. Pain 118:243–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-Basoa M, Gintzler AR 1998 Gestational and ovarian sex steroid antinociception: synergy between spinal κ and δ opioid systems. Brain Res 794:61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gintzler AR, Liu NJ 2001 The maternal spinal cord: biochemical and physiological correlates of steroid-activated antinociceptive processes. Prog Brain Res 133:83–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flake NM, Bonebreak DB, Gold MS 2005 Estrogen and inflammation increase the excitability of rat temporomandibular joint afferent neurons. J Neurophysiol 93:1585–1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diogenes A, Patwardhan AM, Jeske NA, Ruparel NB, Goffin V, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM 2006 Prolactin modulates TRPV1 in female rat trigeminal sensory neurons. J Neurosci 26:8126–8136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, Ness TJ 2000 Sex-related hormonal influences on pain and analgesic responses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 24:485–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papka RE, Srinivasan B, Miller KE, Hayashi S 1997 Localization of estrogen receptor protein and estrogen receptor messenger RNA in peripheral autonomic and sensory neurons. Neuroscience 79:1153–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papka RE, Storey-Workley M, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Collins JJ, Usip S, Saunders PT, Shupnik M 2001 Estrogen receptor-α and β- immunoreactivity and mRNA in neurons of sensory and autonomic ganglia and spinal cord. Cell Tissue Res 304:193–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett HL, Gustafsson JA, Keast JR 2003 Estrogen receptor expression in lumbosacral dorsal root ganglion cells innervating the female rat urinary bladder. Auton Neurosci 105:90–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaban VV, Mayer EA, Ennes HS, Micevych PE 2003 Estradiol inhibits ATP-induced intracellular calcium concentration increase in dorsal root ganglia neurons. Neuroscience 118:941–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DY, Chai YG, Lee EB, Kim KW, Nah SY, Oh TH, Rhim H 2002 17β-estradiol inhibits high-voltage-activated calcium channel currents in rat sensory neurons via a non-genomic mechanism. Life Sci 70:2047–2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves-Tyson TD, Keast JR 2004 Rapid actions of estradiol on cyclic AMP response-element binding protein phosphorylation in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience 129:629–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D 1997 The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 389:816–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D 1998 The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron 21:531–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, Torricelli JR, Evege EK, Price PJ 1993 Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. J Neurosci Res 35:567–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas RS, Winter J, Wren P, Bergmann R, Woolf CJ 1999 Peripheral inflammation increases the capsaicin sensitivity of dorsal root ganglion neurons in a nerve growth factor-dependent manner. Neuroscience 91:1425–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, Sklar LA 2007 GPR30: A G protein-coupled receptor for estrogen. Mol Cell Endocrinol 265–266:138–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler A, Mönter B, Koltzenburg M 2006 The role of the capsaicin receptor TRPV1 and acid-sensing ion channels (ASICS) in proton sensitivity of subpopulations of primary nociceptive neurons in rats and mice. Neuroscience 139:699–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G, Wood JN 1996 Purinergic receptors: their role in nociception and primary afferent neurotransmission. Curr Opin Neurobiol 6:526–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Akopian AN, Sivilotti L, Colquhoun D, Burnstock G, Wood JN 1995 A P2X purinoceptor expressed by a subset of sensory neurons. Nature 377:428–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockayne DA, Dunn PM, Zhong Y, Rong W, Hamilton SG, Knight GE, Ruan HZ, Ma B, Yip P, Nunn P, McMahon SB, Burnstock G, Ford AP 2005 P2X2 knockout mice and P2X2/P2X3 double knockout mice reveal a role for the P2X2 receptor subunit in mediating multiple sensory effects of ATP. J Physiol 567(Pt 2):621–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Neidhart S, Holy C, North RA, Buell G, Surprenant A 1995 Coexpression of P2X2 and P2X3 receptor subunits can account for ATP-gated currents in sensory neurons. Nature 377:432–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrakakis C, Tong CK, Weissman T, Torsney C, MacDermott AB 2003 Localization and function of ATP and GABAA receptors expressed by nociceptors and other postnatal sensory neurons in rat. J Physiol 549(Pt 1):131–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Banning AS, Cockayne DA, Ford AP, Burnstock G, McMahon SB 2003 Bladder and cutaneous sensory neurons of the rat express different functional P2X receptors. Neuroscience 120:667–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington WR, Sheng S, Barnett DH, Petz LN, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS 2003 Activities of estrogen receptor α- and β-selective ligands at diverse estrogen responsive gene sites mediating transactivation or transrepression. Mol Cell Endocrinol 206:13–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björnström L, Sjöberg M 2005 Mechanisms of estrogen receptor signaling: convergence of genomic and nongenomic actions on target genes. Mol Endocrinol 19:833–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedram A, Razandi M, Levin ER 2006 Nature of functional estrogen receptors at the plasma membrane. Mol Endocrinol 20:1996–2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan N, Pfaff DW 2007 Membrane-initiated actions of estrogens in neuroendocrinology: emerging principles. Endocr Rev 28:1–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein AT, Ufret-Vincenty CA, Hua L, Santana LF, Gordon SE 2006 Phosphoinositide 3-kinase binds to TRPV1 and mediates NGF-stimulated TRPV1 trafficking to the plasma membrane. J Gen Physiol 128:509–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs V, Thyagarajan B, Varnai P, Balla A, Balla T, Rohacs T 2007 Dual regulation of TRPV1 by phosphoinositides. J Neurosci 27:7070–7080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Tominaga T 2005 Structure and function of TRPV1. Pflugers Arch 451:143–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, McNaughton PA 2006 Why pain gets worse: the mechanism of heat hyperalgesia. J Gen Physiol 128:491–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldring N, Pike A, Andersson S, Matthews J, Cheng G, Hartman J, Tujague M, Strom A, Treuter E, Warner M, Gustafsson JA 2007 Estrogen receptors: how do they signal and what are their targets. Physiol Rev 87:905–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson S, Makela S, Treuter E, Tujague M, Thomsen J, Andersson G, Enmark E, Pettersson K, Warner M, Gustafsson JA 2001 Mechanisms of estrogen action. Physiol Rev 81:1535–1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CL, O'Malley BW 2004 Coregulator function: a key to understanding tissue specificity of selective receptor modulators. Endocr Rev 25:45–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung YK, Gao Y, Lau KM, Zhang X, Ho SM 2006 ICI 182,780-regulated gene expression in DU145 prostate cancer cells is mediated by estrogen receptor-β/NFκB crosstalk. Neoplasia 8:242–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Bland KI, Frackelton Jr AR 2000 Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Mol Endocrinol 14:1649–1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Frackelton Jr AR, Bland KI 2002 Estrogen action via the G protein-coupled receptor, GPR30: stimulation of adenylyl cyclase and cAMP-mediated attenuation of the epidermal growth factor receptor-to-MAPK signaling axis. Mol Endocrinol 16:70–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revankar CM, Arterburn JM, Mitchell HD, Field AS, Burai R, Corona C, Ramesh C, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER 2007 Synthetic estrogen derivatives demonstrate the functionality of intracellular GPR30. ACS Chem Biol 2:536–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Thomas P 2005 GPR30: a seven-transmembrane-spanning estrogen receptor that triggers EGF release. Trends Endocrinol Metab 16:362–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Pang Y, Filardo EJ, Dong J 2005 Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 146:624–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivacqua A, Bonofiglio D, Albanito L, Madeo A, Rago V, Carpino A, Musti AM, Picard D, Andò S, Maggiolini M 2006 17β-Estradiol, genistein, and 4-hydroxytamoxifen induce the proliferation of thyroid cancer cells through the g protein-coupled receptor GPR30. Mol Pharmacol 70:1414–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivacqua A, Bonofiglio D, Recchia AG, Musti AM, Picard D, Andò S, Maggiolini M 2006 The G protein-coupled receptor GPR30 mediates the proliferative effects induced by 17β-estradiol and hydroxytamoxifen in endometrial cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol 20:631–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D 2000 Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science 288:306–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JB, Gray J, Gunthorpe MJ, Hatcher JP, Davey PT, Overend P, Harries MH, Latcham J, Clapham C, Atkinson K, Hughes SA, Rance K, Grau E, Harper AJ, Pugh PL, Rogers DC, Bingham S, Randall A, Sheardown SA 2000 Vanilloid receptor-1 is essential for inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia. Nature 405:183–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang H, Prescott E, Kong H, Shields S, Jordt S, Basbaum A, Chao M, Julius D 2001 Bradykinin and nerve growth factor release the capsaicin receptor from PtdIns(4,5)P2-mediated inhibition. Nature 411:957–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooner MF, Robichaud P, Carrier JC, Marchand S 2007 Endogenous pain modulation during the formalin test in estrogen receptor β knockout mice. Neuroscience 150:675–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal L, Brandt MR, Cummons TA, Piesla MJ, Rogers KE, Harris HA 2006 An estrogen receptor-β agonist is active in models of inflammatory and chemical-induced pain. Eur J Pharmacol 553:146–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo D, Yabe R, Kurihara T, Saegusa H, Zong S, Tanabe T 2006 Progesterone receptor antagonist is effective in relieving neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol 541:44–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamov O, Yakimchuk K, Morani A, Schwend T, Wada-Hiraike O, Razumov S, Warner M, Gustafsson JA 2007 Estrogen receptor β-deficient female mice develop a bladder phenotype resembling human interstitial cystitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:9806–9809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub RH 2007 The complex role of estrogens in inflammation. Endocr Rev 28:521–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]