Abstract

Mast cells are resident in the brain and contain numerous mediators, including neurotransmitters, cytokines, and chemokines, that are released in response to a variety of natural and pharmacological triggers. The number of mast cells in the brain fluctuates with stress and various behavioral and endocrine states. These properties suggest that mast cells are poised to influence neural systems underlying behavior. Using genetic and pharmacological loss-of-function models we performed a behavioral screen for arousal responses including emotionality, locomotor, and sensory components. We found that mast cell deficient KitW−sh/W−sh (sash−/−) mice had a greater anxiety-like phenotype than WT and heterozygote littermate control animals in the open field arena and elevated plus maze. Second, we show that blockade of brain, but not peripheral, mast cell activation increased anxiety-like behavior. Taken together, the data implicate brain mast cells in the modulation of anxiety-like behavior and provide evidence for the behavioral importance of neuroimmune links.

Keywords: arousal, cromolyn, defecation, psychoneuroimmunology, sash mice

The immune and central nervous systems are traditionally thought to meet different types of requirements for survival. Importantly, there is evidence for dynamic interactions between the two (1–3). While it is known that some immune cells, such as microglia are resident in the brain for surveillance and clearance (4–6), the roles of other immune cells are underexplored. We focus here on mast cells, which are localized not only in the periphery but are also resident in the brain of all mammalian species studied (7–9).

Mast cells are a heterogeneous population of granulocytic cells of the immune system. They contain numerous mediators, including neurotransmitters, cytokines, chemokines, and lipid-derived factors (10). Mast cells in the brain are constitutively active (11), releasing their contents by means of piecemeal or anaphylactic degranulation (12). Additionally, their activity is increased by a wide range of stimuli including immune and non-immune signals such as hormones, like corticotrophin releasing hormone, and various neuropeptides like Substance P and neurotensin (13). Of mast cells over 50 mediators, some are synthesized upon activation (e.g., substance P, somatostatin, cytokines) while others are preformed and stored in granules, allowing for very fast release (e.g., serotonin, histamine) (10, 14, 15). Due to their ability to migrate, they can serve as “single cell glands” delivering mediators “on demand” and influencing neuronal activity (16, 17). Mast cells can act via autocrine and paracrine mechanisms (18), and their secretions can reach a large spatial volume [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. Their granule remnants can even be acquired by neurons through endocytosis (19).

The residence of mast cells in meninges and perivascular locations on the brain side of the blood–brain barrier (7, 20), primarily in thalamic and hippocampal regions (21, 22), indicate that they are strategically situated to initiate neural and vascular responses. However, the function of mast cells in the brain is unknown. A role in normal physiology and behavior is suggested as the brain population of mast cells fluctuates with endocrine status and changes after stress and handling (23–26). Not surprisingly, there are individual differences in the number of brain mast cells within species (27), perhaps associated with behavioral and/or experiential differences.

We explored the possibility that mast cells in the brain might contribute to the modulation of behavior. The analysis entailed a behavioral screen assessing three components of generalized arousal (28), including anxiety-like behavior, locomotor activity, and sensory responsiveness using high-throughput automated assays (29). The availability of the KitW−sh/W−sh (sash−/−) mouse mutant provided a powerful genetic tool for the in vivo analysis of the role of mast cells (30, 31). While lacking mast cells, these mice have levels of major classes of other differentiated hematopoietic and lymphoid cells that are normal (31). Parallel pharmacological manipulation of mast cells permitted confirmation of the function(s) suggested in the mast cell deficient adult. The present work describes genetic and pharmacological loss-of-function studies that examined the relationship of brain mast cells and neural systems modulating behavior.

Results

We assessed the behavior of sash−/− mice in two replicate experimental runs. In the first, we used unrelated C57BL/6 WT mice (the background strain for the sash−/− mutant) as controls, and in the second, we tested heterozygous (sash+/−) littermates. Anxiety-like phenotype was measured by behavioral testing in the open field arena and elevated plus maze and physiological measures of stress-induced defecation. Locomotor activity and sensory responses (to tactile, olfactory, vestibular, auditory, and pain stimuli) were also measured.

Arousal Phenotype of Sash−/− Mice.

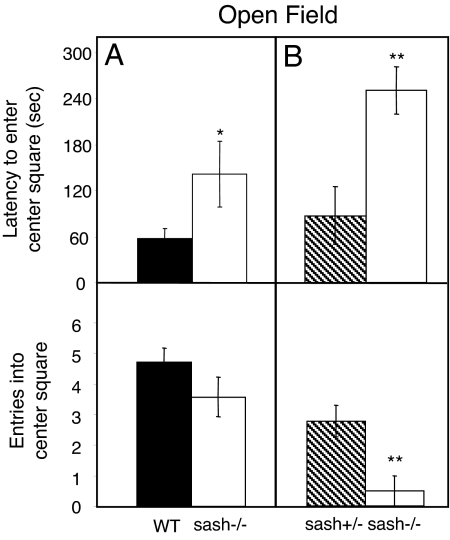

Anxiety-like behavior was assessed using two tests. In the open field test, sash−/− mice displayed more anxiety-like behavior (Fig. 1). The latency of the sash−/− mice to enter the center square was 83 s longer than that of WT mice (sash−/−: 141 s; WT: 58s; P < 0.05), and nearly three times as long as their sash+/− littermates (sash−/−: 268s; sash+/−: 93s, P < 0.01). Sash−/− mice also entered the center square slightly, but not significantly, fewer times than WT mice (3.6 vs. 4.7 times, respectively, P > 0.05). Similarly, sash−/− mice entered the center square fewer times than sash+/− littermates (0.5 vs. 3.7 times, P < 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Mast cell effects on open field behavior. (A) Sash−/− mice (white bars) had a longer latency to enter the center square in the open field test compared to WT mice (black bars). Differences in number of entries into the center square between sash−/− and WT mice were not significant (P > 0.05). (B) Sash−/− mice (white bars), compared to the littermate sash+/− mice (hatched bars), took longer to enter and had fewer entries into the center square. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

The sash−/− mice also displayed more anxiety-like behavior than WT and sash+/− littermate controls in the elevated plus maze (Fig. 2). Sash−/− mice entered open arms ∼3–4 times less than WT and sash+/− littermate controls (P < 0.05). Additionally, sash−/− mice investigated the entrances to the open arms less than WT mice (P < 0.01). There was no difference between the littermate groups in the number of investigations into the open arms. In the measure of latency to enter an open arm, there was a trend, but no significant difference, between the sash−/− and WT animals. However, sash−/− mice displayed a longer latency to enter the open arm compared to their sash+/− littermates (P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Mast cell effects on elevated plus maze behavior. (A) Sash−/− mice (white bars) had fewer entries and investigations into open arms compared to WT control mice (black bars). The latency to enter an open arm was not significantly different between sash−/− and WT mice. (B) Sash−/− mice (white bars) had fewer entries into open arms compared to littermate sash+/− mice (hatched bars). While there was no difference in the number of investigations into open arms, sash−/− mice had significantly longer latency to enter an open arm. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

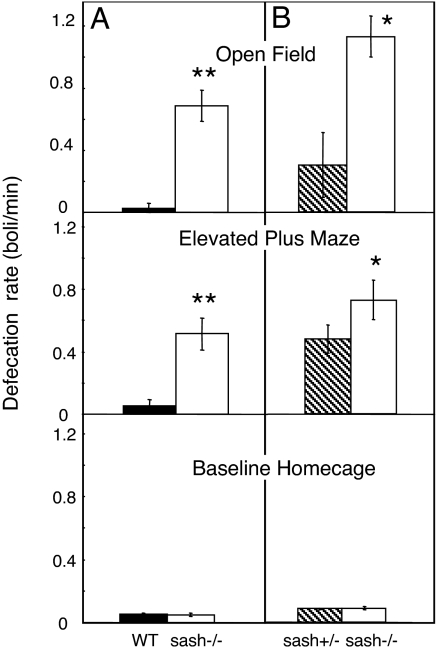

Stress-induced defecation served as a physiological measure of anxiety-like behavior. Defecation during behavioral testing was greater in sash−/− mice compared to WT and sash+/− controls (Fig. 3). Sash−/− mice produced more boli than did WT and sash+/− mice during the open field (P < 0.01 for age matched; P < 0.05 for littermates) and elevated plus maze tests (P < 0.01 for age-matched; P < 0.05 for littermates). Importantly, there were no differences in baseline defecation, measured by average rate or weight of defecation over a 24-h period in their home cage. There were also no differences between sash−/− mouse body weights and that of WT or sash+/− controls at time of sacrifice.

Fig. 3.

Mast cell deficiency effects on defecation. (A) The excretion rate was higher in sash−/− mice (white bars) compared to WT mice (black bars) during behavioral testing in the open field arena and elevated plus maze. Baseline home cage defecation in sash−/− and WT mice was not significantly different. (B) Sash−/− mice (white bars) had higher defecation rates compared to littermate sash+/− mice (hatched bars) in all behavioral tests. Baseline home cage defecation was not different between genotypes. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

While we saw a mast cell effect on anxiety behavior, there were no differences in any of the other arousal behaviors tested (SI Methods). Sash−/− mice showed no differences in baseline locomotor activity compared to WT or sash+/− littermate controls. Additionally, there were no differences between groups in the responses to tactile, olfactory, vestibular, auditory, and pain stimuli (Figs. S2–S4).

It is well established that brain mast cells contribute to the neural pool of histamine (32–34). To confirm mast cell contribution to brain anime levels, we measured histamine in whole brain homogenates. Sash−/− mice had 31.6% of WT control levels and 41.9% of sash+/− littermate levels of brain histamine (3.6 nM/g in sash−/− compared to 11.4 and 8.6 nM/g in WT and sash+/− littermate controls respectively; Fig. S5). The results confirm that mast cell deficiency causes a reduction in brain histamine.

Pharmacological Blockade of Mast Cells.

To assess the contribution of central nervous system versus peripheral mast cells to the modulation of anxiety-like behavior in the adult mouse, we used disodium cromoglycate (cromolyn) to block mast cell degranulation (35). Cromolyn does not cross the blood brain barrier (36) and therefore we could distinguish the role of central and peripheral mast cell populations with i.p. versus i.c.v. injections. The WT mice were tested in a counterbalanced within subject experimental design to compare behavioral responses to i.p. and lateral i.c.v. cromolyn injection.

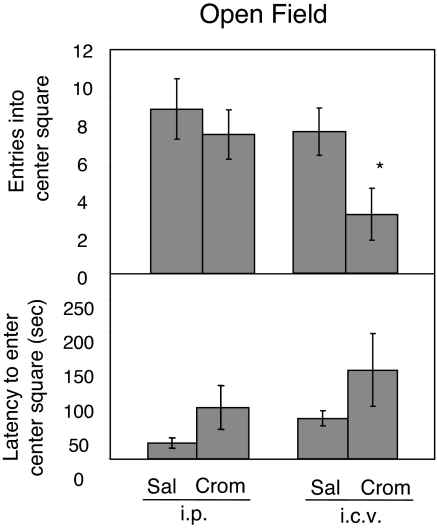

Central, but not peripheral, injection of cromolyn into WT mice increased anxiety-like behavior in the open field arena (Fig. 4). The i.c.v.-injected animals had 58% fewer entries into the center square compared to mice injected with saline i.c.v. or cromolyn i.p. [3.3 vs. 8 (saline i.c.v.) and 7.9 (cromolyn i.p.) occurrences, P < 0.05]. There was no significant difference between mice injected i.p. with cromolyn or saline (P > 0.05). In mice injected with i.c.v. cromolyn, there was a suggestive, but not significant, increase in the latency to enter the center of the open field arena (139 s) compared to i.c.v saline injected (64 s) and also i.p. injected animals (P = 0.16). Cromolyn injected i.p. did not significantly affect the latency to enter or the total number of entries into the center square compared to i.p. saline injected controls (P > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Cromolyn effects on open field behavior. Cromolyn injected i.p. into WT animals had no significant effects on open field behavior. There were no differences between saline and cromolyn injected animals in number of entries into the center square or the latency to enter the center square. Cromolyn injected into the lateral ventricle resulted in decreased exploratory behavior. Compared to saline injected controls, WT animals injected with cromolyn i.c.v. had fewer entries into the center square. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05.

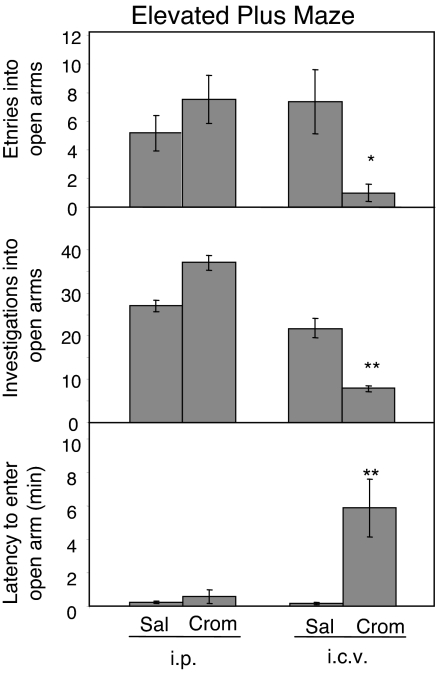

In the elevated plus maze, as in the open field arena, i.c.v. but not i.p. injection of cromolyn increased anxiety-like behavior (Fig. 5). When injected i.c.v., cromolyn caused a 79% decrease in the number of entries and an 86% decrease in the number of investigations into the open arms compared to i.p. cromolyn injected mice (entries: 1.0 vs. 7.5 occurrences, P < 0.05; investigations: 7.9 vs. 37.0 occurrences, P < 0.01). Central cromolyn also increased the latency to enter the open arm compared to animals injected i.p. with cromolyn (352 vs. 33 s; P < 0.01). The behavior in animals injected with cromolyn peripherally did not differ from that of animals injected with saline i.p. (P > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Cromolyn effects on elevated plus maze behavior. Cromolyn injected i.p. into WT animals had no significant effects on behavior in the elevated plus maze. There were no differences between saline and cromolyn injected animals in number of entries or investigations into the open arms or the latency to enter an open arm. Cromolyn injected i.c.v. decreased the number of entries into and investigations into open arms. The latency to enter an open arm was increased compared to saline-injected controls. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

There were no significant effects of cromolyn on defecation. Neither i.c.v. nor i.p. injection of cromolyn caused changes in stress-induced defecation rate during the open field test or elevated plus maze.

Discussion

In the present experiments, using a genetic model, we demonstrate that a specific cellular element of the hematopoietic system, the mast cell, mediates the expression of anxiety-like behavior but has no effect on sensory arousal and locomotor responses. Using a pharmacological manipulation, we show that this is an effect of mast cells in modulating behavior of the adult rather than the result of developmental abnormalities in the mast cell deficient mouse. Additionally, the blockade of central, but not peripheral, mast cells affects anxiety-like behavior, revealing a central nervous system site of action. While the multitude of their mediators and triggers of activation prohibit the determination of which mast cell constituent(s) are responsible for the altered behavior, we show that brain histamine levels are decreased in the absence of these cells. This confirms that brain mast cells can contribute to the available CNS neurochemical pool.

Mast Cells and Emotionality.

The present results are consistent with previous, highly suggestive evidence of associations between mast cells and emotionality. Food allergies, asthma and irritable bowel syndrome (all mast cell mediated pathologies) are commonly linked to trait-anxiety in humans but are potentially confounded by the stressful recurrent episodes themselves (37, 38). However, induction of an asthmatic or food allergy response in mice causes mast cell dependent increases in anxiety-like behavior and activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis (39, 40). Additionally, patients afflicted with systemic mastocytosis, a disease characterized by an increase in the number of mast cells (41), report low arousal states, lethargy, and induction of coma (42, 43). These symptoms are reversed by treatment that includes histamine antagonists and cromolyn. Last, the incidence of autistic spectrum disorders is 6.75 higher in mastocytosis patients or their immediate relatives than in the general population (44).

Mast Cells Are Pluripotential.

Mast cell-dependent changes in behavior are not likely due to a single mast cell mediator, but rather to multiple interacting chemicals and neural systems. Of the many known mast cell mediators, including neurotransmitters, cytokines, and lipid derived factors (10), many have been individually implicated in the modulation of behavior. Histamine is implicated in the regulation of the sleep–wake cycle (45), as well as other arousal-related systems including sex behaviors and anxiety (46, 47). In fact, histamine has been assigned both anxiolytic (48) and anxiogenic (49) effects, with opposing roles attributed to H1 versus H2 receptors (50). Serotonin functions both as a transmitter affecting many systems including aggression, appetite, and mood (51), and also as a trophic factor influencing neurogenesis and thereby affecting emotionality and memory (52, 53). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors increase serotonin signaling and decrease anxiety (54, 55); therefore, a lack of mast cell derived serotonin may result in an increase in anxiety-like behaviors. Mast cell derived cytokines act as neuromodulators having effects on systems controlling behavior. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1, and interleukin-6 act on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and stress behavior (56). TNF-α also plays a role in the regulation of body temperature and the sleep–wake cycle (57, 58). Lipid-derived factors like prostaglandin D2 also have known roles as neuromodulators, contributing to the regulation of the sleep, pain, and body temperature regulation (59–61). Given the large number of mediators, mast cells most likely have multifaceted interactions with brain systems controlling behavior.

Mast Cells Are Active Both Constitutively and Following Stimulation.

Since a majority of thalamic mast cells are active in the basal state (11, 62), factors affecting mast cell numbers in the brain are likely to be neurophysiologically important. Many apparently unrelated manipulations, including handling, sex, and stress, increase the number of brain mast cells, and it should be noted that all of these manipulations increase CNS arousal. An early study by Persinger showed that simple gentle handling of rat pups decreased numbers of mast cells in the brain developmentally, most likely representing an increase in degranulation (25). Psychological stressors induced through social defeat and isolation stress increased the number of mast cells in the brain (26, 63). Last, gonadal hormones from conspecifics during mating also increase mast cell number and activation in the brain (23, 62, 64).

Immune Cells in Normal CNS Physiology.

While much of the evidence for immune system effects on the brain have come from disease states, other evidence, including data presented here, points to the role of neuroimmune interactions in normal physiology. The former line of research shows that dysregulation of the immune system can negatively impact brain functioning. Cytokines released in the periphery during an immune response gain access to the brain (65) and modulate many brain systems, including effect, cognition, and pain processing (65, 66). Specifically, interferons and interleukins have been causally implicated in mediating depression (67). Interestingly, this has led to the immune system becoming a focus of novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of neurological disorders including psychiatric diseases (44, 68). However, the present study joins a growing literature investigating the role of immune cells in the healthy brain. CNS-specific T-cells contribute to hippocampal neurogenesis in adults with consequences for the formation of spatial memories (69). Also, major histocompatibility complex molecules (expressed on dendritic cells, T-cells, microglia, and mast cells in the brain) are implicated in neuronal synapse development (70) and play a role in synaptic plasticity (71).

Overall, our data provide evidence for a direct association of brain mast cells impacting anxiety-like behavior. Given that they can change the signaling milieu of the brain, we suggest that mast cells provide a functional link through which the immune system interacts with the brain. The results provide evidence of the behavioral importance of immune cells in the brain.

Materials and Methods

Mast Cell Deficient Mice.

Mast cell deficient KitW−sh/W−sh (sash−/−) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (B6.Cg-KitW−sh/HNihrJaeBsmJ; strain 5051). Sash−/− mice carry a mutation upstream from the white spotting (W) locus causing disruption of the 5′ regulatory sequences and therefore reduced signaling through c-kit tyrosine kinase (30). This reduced c-kit expression in the bone marrow causes an inability of hematopoietic stem cells to differentiate into mast cell precursors resulting in a complete lack of mast cells (31, 72). No other known disruptions in the development of hematopoietic stem cell derivatives or any other irregularities in c-kit receptor mRNA or protein expression, with the exception of melanocytes (causing irregular fur pigmentation), have been found (30).

The studies were first completed with male sash−/− (n = 8) and unrelated age-matched C57BL/6 WT control mice (n = 8). A second cohort, run with sash+/− littermates (n = 7) serving as controls for sash−/− mice (n = 6) allowed us to control for other genetic variability and epigenetic factors that might affect behavior. All animals were male and housed in a 12:12 light–dark cycle and food and water were available ad libitum. All experimental procedures were in accordance with the protocols of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Rockefeller University.

Cromolyn Blockade of Mast Cell Degranulation.

For examination of the response to disodium cromoglycate (cromolyn, Sigma Aldrich), C57/BL6 WT animals (n = 14, Jackson Laboratory) were used. All mice were male. Mice were anesthetized with a Ketamine (100 mg/kg)-Xylazine (13 mg/kg) mixture and implanted stereotaxically (David Kopf Intruments) with chronic indwelling cannulas (Plastics One). Tips of the cannula were directed 0.2-mm dorsal to the right lateral ventricle (bregma, 0.5 mm; mid, 1.2 mm; skull, 2.5 mm) for use with an injector cannula 0.2 mm longer than the guide cannula. Following recovery, animals were subject to a 2 × 2 study design receiving either saline or cromolyn via i.p. or i.c.v. injections. Cromolyn doses were 10 mg/kg (i.p.) and 50 μg/3 μl (i.c.v.). Cromolyn or saline was injected for 3 days, and behavioral testing was completed on the third day after injection.

Behavioral Testing

Open field arena.

For assessment of open field behavior, mice were placed individually into a 40 × 40 cm brightly lit, Plexiglas open field arena. The bottom was demarcated into a 5 × 5 grid making 25 equal-sized (8 × 8 cm) squares. Mice were allowed to explore the arena undisturbed for 5 min. Video tapes were scored by two experimenters blind to the study for latency to enter and number of entries into the center square.

Elevated plus maze.

The elevated plus maze was elevated 30 cm from the ground with a 5 cm × 5 cm center platform and 4 radial arms (5 cm wide × 30 cm long) with two opposing “closed” arms encased by 15-cm high opaque black walls (Rockefeller University Instrument Shop, New York, NY). Mice were placed in the center of the maze oriented toward an open radial arm and allowed to explore undisturbed and videotaped for 10 min. Video tapes were scored by experimenters blind to the study for latency to enter an open arm, number of entries into open arms, and instances of investigations into open arms.

Defecation.

The number of boli was counted for each animal after behavioral testing. For measures of baseline defecation, animals were placed individually in bins with a grid bottomed floor without bedding for 24 h. Dry weight and number of boli were recorded. Defecation data are represented as average rates (number of boli/minute).

Statistical Analysis.

Comparisons between sash−/− mice and WT controls or heterozygous littermates were made using one-way ANOVA. Results from the pharmacological loss-of-function experiment were compared using two-way ANOVA (treatment × injection route). Pairwise multiple comparisons were performed with Tukey's HSD test when appropriate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Akhila Iyer and Isabelle Carren-LeSauter for help with behavioral scoring and Drs. Frances Champagne, Joseph LeSauter and Matthew Butler for their helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript. Support provided by Grants NICHD 05751–33 (to D.P.) and NIMH 67782 and NSF IOS-05–54514 (to R.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0809479105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Steinman L. Elaborate interactions between the immune and nervous systems. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:575–581. doi: 10.1038/ni1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capuron L, et al. Association of exaggerated HPA axis response to the initial injection of interferon-alpha with development of depression during interferon-alpha therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1342–1345. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenkranz MA, et al. Affective style and in vivo immune response: Neurobehavioral mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11148–11152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1534743100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science. 2005;308:1314–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kettenmann H. Neuroscience: The brain's garbage men. Nature. 2007;446:987–989. doi: 10.1038/nature05713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanisch UK, Kettenmann H. Microglia: Active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1387–1394. doi: 10.1038/nn1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hough LB. Cellular localization and possible functions for brain histamine: Recent progress. Prog Neurobiol. 1988;30:469–505. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(88)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silver R, Silverman AJ, Vitkovic L, Lederhendler II. Mast cells in the brain: Evidence and functional significance. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:25–31. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)81863-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dropp JJ. Mast cells in mammalian brain. Acta Anat (Basel) 1976;94:1–21. doi: 10.1159/000144540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall JS. Mast-cell responses to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:787–799. doi: 10.1038/nri1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Florenzano F, Bentivoglio M. Degranulation, density, and distribution of mast cells in the rat thalamus: A light and electron microscopic study in basal conditions and after intracerebroventricular administration of nerve growth factor. J Comp Neurol. 2000;424:651–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dvorak AM, et al. Ultrastructural evidence for piecemeal and anaphylactic degranulation of human gut mucosal mast cells in vivo. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1992;99:74–83. doi: 10.1159/000236338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paus R, Theoharides TC, Arck PC. Neuroimmunoendocrine circuitry of the ‘brain-skin connection. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson D, Krenger W. Interactions of mast cells with the nervous system—recent advances. Neurochem Res. 1992;17:939–951. doi: 10.1007/BF00993271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penner R, Neher E. The patch-clamp technique in the study of secretion. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:159–163. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverman AJ, Sutherland AK, Wilhelm M, Silver R. Mast cells migrate from blood to brain. J Neurosci. 2000;20:401–408. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00401.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovacs P, Hernadi I, Wilhelm M. Mast cells modulate maintained neuronal activity in the thalamus in vivo. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;171:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyce JA. Mast cells and eicosanoid mediators: A system of reciprocal paracrine and autocrine regulation. Immunol Rev. 2007;217:168–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilhelm M, Silver R, Silverman AJ. Central nervous system neurons acquire mast cell products via transgranulation. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2238–2248. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalil M, et al. Brain mast cell relationship to neurovasculature during development. Brain Res. 2007;1171:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendrix S, et al. The majority of brain mast cells in B10. PL mice is present in the hippocampal formation. Neurosci Lett. 2006;392:174–177. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taiwo OB, Kovacs KJ, Larson AA. Chronic daily intrathecal injections of a large volume of fluid increase mast cells in the thalamus of mice. Brain Res. 2005;1056:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asarian L, Yousefzadeh E, Silverman AJ, Silver R. Stimuli from conspecifics influence brain mast cell population in male rats. Horm Behav. 2002;42:1–12. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovacs KJ, Larson AA. Mast cells accumulate in the anogenital region of somatosensory thalamic nuclei during estrus in female mice. Brain Res. 2006;1114:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Persinger MA. Handling factors not body marking influence thalamic mast cell numbers in the preweaned albino rat. Behav Neural Biol. 1980;30:448–459. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(80)91283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cirulli F, Pistillo L, de Acetis L, Alleva E, Aloe L. Increased number of mast cells in the central nervous system of adult male mice following chronic subordination stress. Brain Behav Immun. 1998;12:123–133. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1998.0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persinger MA. Brain mast cell numbers in the albino rat: Sources variability. Behav Neural Biol. 1979;25:380–386. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(79)90448-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfaff D. Brain Arousal and Information Theory: Neural and Genetic Mechanisms. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arrieta-Cruz I, Pfaff DW, Shelley DN. Mouse model of diffuse brain damage following anoxia, evaluated by a new assay of generalized arousal. Exp Neurol. 2007;205:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duttlinger R, et al. W-sash affects positive and negative elements controlling c-kit expression: Ectopic c-kit expression at sites of kit-ligand expression affects melanogenesis. Development. 1993;118:705–717. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grimbaldeston MA, et al. Mast cell-deficient W-sash c-kit mutant Kit W-sh/W-sh mice as a model for investigating mast cell biology in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:835–848. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62055-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bugajski AJ, Chlap Z, Bugajski J, Borycz J. Effect of compound 48/80 on mast cells and biogenic amine levels in brain structures and on corticosterone secretion. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;46:513–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oishi R, Itoh Y, Fukuda T, Araki Y, Saeki K. Comparison of the size of neuronal and non-neuronal histamine pools in the brain of different rat strains. J Neural Transm. 1988;73:65–69. doi: 10.1007/BF01244623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grzanna R, Shultz LD. The contribution of mast cells to the histamine content of the central nervous system: A regional analysis. Life Sci. 1982;30:1959–1964. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90434-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theoharides TC, Sieghart W, Greengard P, Douglas WW. Antiallergic drug cromolyn may inhibit histamine secretion by regulating phosphorylation of a mast cell protein. Science. 1980;207:80–82. doi: 10.1126/science.6153130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norris AA. Pharmacology of sodium cromoglycate. Clin Exp Allergy. 1996;26(Suppl 4):5–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1996.tb00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lehrer PM, Isenberg S, Hochron SM. Asthma and emotion: A review. J Asthma. 1993;30:5–21. doi: 10.3109/02770909309066375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Addolorato G, et al. Anxiety and depression: A common feature of health care seeking patients with irritable bowel syndrome and food allergy. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1559–1564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Costa-Pinto FA, Basso AS, Russo M. Role of mast cell degranulation in the neural correlates of the immediate allergic reaction in a murine model of asthma. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:783–790. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costa-Pinto FA, et al. Neural correlates of IgE-mediated allergy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1088:116–131. doi: 10.1196/annals.1366.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Metcalfe DD. Mast cells and mastocytosis. Blood. 2008;112:946–956. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-078097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tajima Y, et al. Sequential magnetic resonance features of encephalopathy induced by systemic mastocytosis. Intern Med. 1994;33:23–26. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.33.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boncoraglio GB, et al. Systemic mastocytosis: A potential neurologic emergency. Neurology. 2005;65:332–333. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000168897.35545.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Theoharides TC, Doyle R, Francis K, Conti P, Kalogeromitros D. Novel therapeutic targets for autism. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown RE, Stevens DR, Haas HL. The physiology of brain histamine. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63:637–672. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Donoso AO, Broitman ST. Effects of a histamine synthesis inhibitor and antihistamines on the sexual behavior of female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1979;66:251–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00428315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ikarashi Y, Yuzurihara M. Experimental anxiety induced by histaminergics in mast cell-deficient and congenitally normal mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;72:437–441. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zarrindast MR, Valizadegan F, Rostami P, Rezayof A. Histaminergic system of the lateral septum in the modulation of anxiety-like behaviour in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dere E, et al. Changes in motoric, exploratory and emotional behaviours and neuronal acetylcholine content and 5-HT turnover in histidine decarboxylase-KO mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1051–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuzurihara M, et al. Effects of drugs acting as histamine releasers or histamine receptor blockers on an experimental anxiety model in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:145–150. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lucki I. The spectrum of behaviors influenced by serotonin. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gould E. Serotonin and hippocampal neurogenesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:46S–51S. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaspar P, Cases O, Maroteaux L. The developmental role of serotonin: news from mouse molecular genetics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:1002–1012. doi: 10.1038/nrn1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Handley SL. 5-Hydroxytryptamine pathways in anxiety and its treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;66:103–148. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)00004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dulawa SC, Holick KA, Gundersen B, Hen R. Effects of chronic fluoxetine in animal models of anxiety and depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1321–1330. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dunn AJ. Cytokine activation of the HPA axis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;917:608–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Conti B, Tabarean I, Andrei C, Bartfai T. Cytokines and fever. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1433–1449. doi: 10.2741/1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krueger JM, Obal FJ, Fang J, Kubota T, Taishi P. The role of cytokines in physiological sleep regulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;933:211–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ueno R, Honda K, Inoue S, Hayaishi O. Prostaglandin D2, a cerebral sleep-inducing substance in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1735–1737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.6.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ueno R, et al. Role of prostaglandin D2 in the hypothermia of rats caused by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:6093–6097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.19.6093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mong JA, et al. Estradiol differentially regulates lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase transcript levels in the rodent brain: Evidence from high-density oligonucleotide arrays and in situ hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:318–323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilhelm M, King B, Silverman AJ, Silver R. Gonadal steroids regulate the number and activational state of mast cells in the medial habenula. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1178–1186. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.3.7352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bugajski AJ, Chlap Z, Gadek M, Bugajski J. Effect of isolation stress on brain mast cells and brain histamine levels in rats. Agents Actions. 1994;41:C75–C76. doi: 10.1007/BF02007774. Spec No. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang M, Chien C, Lu K. Morphological, immunohistochemical and quantitative studies of murine brain mast cells after mating. Brain Res. 1999;846:30–39. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maier SF. Bi-directional immune-brain communication: Implications for understanding stress, pain, and cognition. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17:69–85. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(03)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Irwin MR, Miller AH. Depressive disorders and immunity: 20 years of progress and discovery. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:374–383. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: Inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Di Filippo M, Sarchielli P, Picconi B, Calabresi P. Neuroinflammation and synaptic plasticity: Theoretical basis for a novel, immune-centred, therapeutic approach to neurological disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:402–412. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ziv Y, et al. Immune cells contribute to the maintenance of neurogenesis and spatial learning abilities in adulthood. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:268–275. doi: 10.1038/nn1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huh GS, et al. Functional requirement for class I MHC in CNS development and plasticity. Science. 2000;290:2155–2159. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oliveira AL, et al. A role for MHC class I molecules in synaptic plasticity and regeneration of neurons after axotomy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17843–17848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408154101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kitamura Y, Fujita J. Regulation of mast cell differentiation. Bioessays. 1989;10:193–196. doi: 10.1002/bies.950100604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.