Abstract

The use of luciferase reporters has become a precise, noninvasive, high-throughput method for real-time monitoring of promoter activity in living cells, especially for rhythmic biological processes such as circadian rhythms. We developed a destabilized firefly luciferase as a reporter for rhythmic promoter activity in both the cell division and respiratory cycles of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae in which real-time luminescence reporters have not been previously applied. The continuous output of light from luciferase reporters allowed us to explore the relationship between the cell division cycle and the yeast respiratory oscillation, including the observation of responses to chemicals that cause phase shifting of the respiratory oscillations. Destabilized firefly luciferase is a good reporter of cell cycle position in synchronized or partially synchronized yeast cultures, in both batch and continuous cultures. In addition, the oxygen dependence of luciferase can be used under certain conditions as a genetically encodable oxygen monitor. Finally, we use this reporter to show that there is a direct correlation between premature induction of cell division and phase resetting of the respiratory oscillation under the continuous culture conditions tested.

Keywords: circadian rhythms, luciferase reporter, metabolic cycle, Saccharomyces, ultradian rhythms

Measuring regular changes within organisms over time is essential for understanding rhythmic biological phenomena and the design principles of biological circuits (1). Historically, such measurements were limited to observing behavioral, morphological, or physiological parameters (2). Later biochemical advances allowed scientists to assay cellular extracts for the rhythmic occurrence of specific molecules. All of these methods are labor intensive, relatively low-throughput, and/or require the destruction of the organism (e.g., to make a cell extract). Even modern assay techniques, such as microarrays, require the destruction of biological samples. However, the use of in vivo genetic reporting systems allows us to witness an organism's rhythmic gene activity in real time and to characterize biological oscillations at a molecular level. For example, the field of circadian rhythms (period ≈24 h) was revolutionized by the application of luminescence reporting of clock-controlled promoter activities as a noninvasive real-time assay (3–7). These luminescence reporting applications have extended to high-throughput screening of circadian mutants (8, 9) and traps for clock-controlled promoters and enhancers (10, 11).

For circadian applications in eukaryotic cells from filamentous fungi to plants to animals, the luminescence reporter of choice has been firefly luciferase (Luc) (3, 4, 6, 7, 12, 13). The Luc gene can be coupled to an endogenous promoter and used as a genetically encodable, noninvasive reporter of the promoter's activity. Firefly Luc is a 62-kDa protein that catalyzes the oxidation of the bioluminescent substrate “luciferin” in the presence of O2, ATP, and Mg+2; the energy released by this reaction produces an electronically excited state, which then emits a photon (4). Light emission is therefore an immediate and measurable indicator of Luc activity. The relatively short half-life of luciferase (≈2–4 h) allows its expression to dynamically reflect transcriptional activity on a faster time scale than longer-lived reporters such as GFP, β-Gal, or CAT (4, 14, 15). Additionally, Luc does not require excitation from an external light source as do fluorescent reporters, thereby avoiding complications such as photobleaching, phototoxicity, and endogenous responses to light. Most importantly for applications to yeast, Luc reporters circumvent the problematic autofluorescence that stems from complex media components, dense cultures, or intense excitation needed to detect low concentrations of fluorescent reporters.

Molecular tools for characterizing subcellular spatial expression and localization of yeast proteins have revolutionized investigations of where proteins reside within yeast, for example, by using GFP-fusion proteins (16). However, even though Luc has often been the reporter of choice for temporal events such as circadian rhythms, it has not yet been applied as a real-time, noninvasive reporter in yeast. Rhythmic phenomena in yeast include the cell division cycle (CDC) and yeast respiratory oscillations (YROs). The former phenomenon is intrinsic to all cells, but the observation of YROs has been limited to several strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae that grow under specific conditions of continuous culture. Although the phenomenon has been known for decades (17), laboratories are only now beginning to elucidate the mechanisms underlying its stability and maintenance of population synchrony (18–21). A coincidence between the CDC and YROs has been described (20, 22) but the relationship between these two rhythmic phenomena is unclear (23, 24).

In this article, we modified firefly Luc to function as a rapid, continuous, real-time reporter of promoter activity for cell-cycle regulated genes in populations of yeast and use this reporter as a gauge of gene activity during the CDC and in undisturbed, dense cultures that are exhibiting YROs. This reporter provides an inexpensive, dependable read-out of a synchronized yeast population's phase in the CDC and thus can serve for some experiments as an alternative to the labor-intensive and/or costly methods of microscopy, FACS, microarray, or blotting. Moreover, we use this yeast reporter to probe the interdependency of the CDC and YROs, showing that there is a direct correlation between premature induction of cell division and phase resetting in YROs under the conditions tested.

Results and Discussion

The half-life of native firefly Luc in mammalian cells ranges from 1.4–4.4 h (13, 25). While this rate of turnover is adequate for measuring circadian oscillations that occur over a 24-h time course, cycles in yeast (e.g., the CDC and YROs) occur more rapidly, on the order of 40 min to 12 h or more depending on the conditions (26, 27). A reporter with a 1–4 h turnover would not be adequate for accurately reporting oscillations occurring over time spans of 0.5–6 h (4). Therefore, for measuring more rapid changes in promoter activity, we developed a Luc reporter with a shorter half-life by modifying the coding region of firefly Luc to include the destabilizing PEST sequence from the CLN2 gene of S. cerevisiae (14). This modification shortened the half-life of Luc's activity in yeast from ≈3 h to 35 min [see supporting information (SI) Fig. S1 and Table S1]. This destabilized Luc also showed a lower level of background expression and a level of induction over background that was 13 times greater than the unmodified Luc, providing a greater dynamic range than the unmodified version.

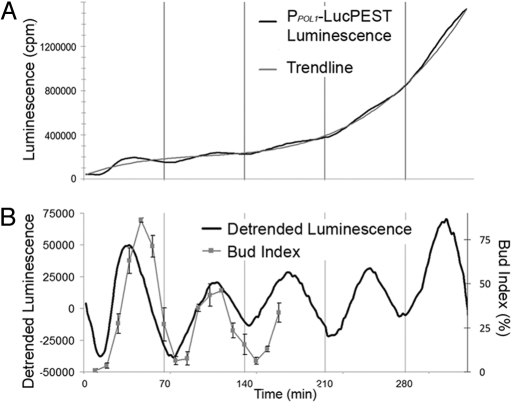

Luc can be used as an accurate reporter of the yeast CDC by expressing the destabilized Luc under the control of a cell cycle-regulated promoter. POL1 encodes the largest subunit of DNA polymerase α (28) and is transcribed during the late G1 to early S phase of the cell cycle (29). The reporter gene was fused to the POL1 promoter (PPOL1-LucPEST) and integrated into the genome of the MATα, bar1 strain LHY3865. These yeast, released from cell-cycle arrest with alpha factor, showed at least five noticeable oscillations of luminescence with a period of ≈70 min (Fig. 1A). The luminescence signal increased with time as the cell density of the culture increased, but the amplitude of the oscillation dampened. When the luminescence data were detrended by subtraction of the luminescence trace from a third order polynomial trendline, the ongoing oscillation became more apparent (Fig. 1B). A similar result is obtained when luminescence data from a separate, asynchronously growing culture of the same yeast were used to detrend the data from the synchronized culture (Fig. S2). This luminescence oscillation of the synchronized culture coincided with the period of the microscopically determined population budding percentage (bud index) that was taken for 3 h; the luminescence rhythm phase leads the rhythm of the bud index by ≈10 min (Fig. 1B). These data indicate that the luminescence rhythm (reflecting PPOL1 activity) is a good reporter of both CDC phase and period.

Fig. 1.

Luminescence from PPOL1-LucPEST oscillates with the CDC. (A) Luminescence from a yeast culture transformed with PPOL1-LucPEST was recorded over time. The culture was arrested with α-factor for 3 h and released (A, black line). Overall luminescence from the culture increased over time as cell density increased roughly following a trend described by a 3rd order polynomial (A, gray line). The influence of growth was detrended from the data by subtracting the polynomial from the luminescence of the synchronized culture (B, black line). The difference was then compared with the oscillation of cell division calculated by microscopically scoring bud index (B, gray line) (n = 3–5 samples of >100 cells each per time point, ± S.D.).

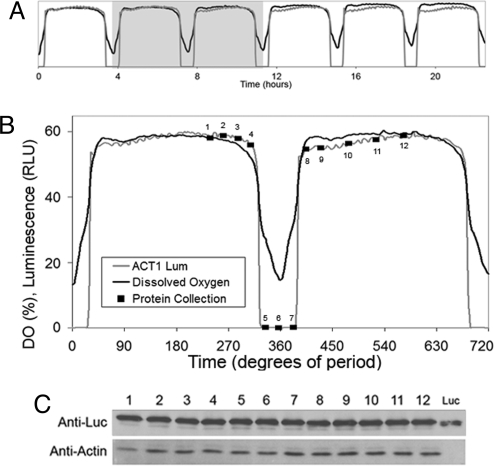

A YRO is characterized by a robust oscillation of dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations (18, 20–22, 26, 27, 30, 31) as well as some degree of synchronous cell division (18, 20, 22, 26). DO can be monitored continuously and automatically with an electrode, but DO electrodes can only be used in relatively large volumes of liquid cultures. Luminescence reporting technology can potentially allow intracellular O2 levels to be monitored under a wider range of culture conditions. Luc is an oxygen-dependent enzyme that maintains a relatively stable light output when [O2] remains >5% (≈25% atmospheric saturation), declines gradually as [O2] falls <5%, and plummets at [O2] below ≈2% (32, 33). Because DO oscillates between 2–10% (≈10–50% atmospheric saturation) over the course of the YROs, the medium is periodically depleted of one of Luc's cofactors. The interval of relative hypoxia inhibits Luc activity, thereby “masking” promoter activity information. To develop a Luc reporter for the O2 decrease during the YROs, we used unmodified Luc for its greater stability and fused Luc to the constitutively expressed (34) promoter for actin (PACT1-Luc). Fig. 2 shows that the luminescence from yeast transformed with PACT1-Luc closely matches that of the DO trace. An immunoblot of yeast cells collected over one cycle of a YRO reveals a relatively constant amount of an anti-Luc-reacting protein. These immunoblot results confirm that PACT1 is driving relatively constant expression of Luc and the correlation of dim luminescence with low DO levels supports the conclusion that the luminescence signal disappears at low O2 levels. Therefore, the PACT1-Luc reporter could be used as a genetically encodable, in vivo monitor for low O2 levels in situations where a DO probe is not practical, for example, in colonies or very small culture vessels.

Fig. 2.

The PACT1-Luc reporter can be used to monitor intervals of low oxygen tension during the YRO. (A) Six cycles of the YRO showing DO (black trace) and luminescence from PACT1-Luc (gray trace). The two cycles highlighted in the gray box are shown in panel B. (B) Total protein was prepared from cell samples taken at various phases of the YRO (time points 1–12). DO is plotted as % atmospheric saturation. (360° = 3.75 h in this experiment.) (C) Reporter protein concentration shows stable expression over the YRO. Immunoblots of total protein using anti-Luc and anti-actin (loading control) antibodies show that Luc protein concentration is stable across the oscillation when driven by the actin promoter, even during the hypoxic mask. The lane marked Luc is a control of 20 ng of purified Luc. The absence of luminescence signal during the hypoxic mask therefore is likely because of low O2 levels rather than a change in reporter protein concentration.

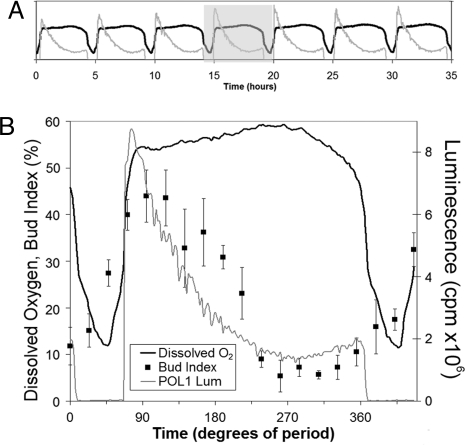

Can Luc reporters be used to study gene expression during the YRO? Under some conditions, yeast cells divide in synchrony during the YRO [see below (20, 26)], and mRNA levels of various genes oscillate either in or out of phase with the DO oscillation as monitored by microarrays (18, 20) or Northern blots (21). Microarray/blot methods are informative, but they are expensive, labor intensive, and are limited by the frequency of sampling over the YRO. We tested the PPOL1-LucPEST luminescent reporter in continuous, oscillating cultures of strain CEN.PK to determine whether it could report promoter activity and cell cycle position continuously in real time without the need for sampling. Fig. 3A shows seven consecutive YRO cycles over a 35-h time course. In each cycle, luminescence peaks soon after DO rises and then gradually decays. Samples were taken from one cycle of a YRO and assayed for the bud index. The luminescence signal from PPOL1-LucPEST followed the budding percentage except for recurring times of culture hypoxia (Fig. 3B). The luminescence traces can be roughly corrected for the intervals of hypoxia (Fig. S3); with this correction, the bud index rhythm clearly phase-lags that of PPOL1-LucPEST luminescence. Therefore, as long as the luminescence data are corrected for the hypoxic masking, the data are very similar to those shown for PPOL1-LucPEST in yeast cells that are synchronously dividing under conditions in which O2 is not limiting (Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Luminescent PPOL1-LucPEST reporter in yeast undergoing respiratory oscillations in continuous culture. (A) The reporter shows real-time POL1 promoter activity over a 35-h time course (RLU, relative light units). (A, gray line) of the YRO. Oscillating DO concentration (A, black line) measured continuously with a DO electrode tracks the YRO. (B) Samples were removed from the oscillating culture at different phases during the gray highlighted section of panel A and cells were scored for bud index to show that luminescence from the PPOL1-LucPEST reporter corresponds with a rhythm of cell division in the population (n = 3–9 samples/time point, ± SD). Luminescence (gray) and DO levels (black) are also shown for comparison (100% DO = media saturated by atmospheric O2). Hypoxia masks the luminescence signal when DO concentration drops below approximately 40% saturation. (360° = 5 h in this experiment.)

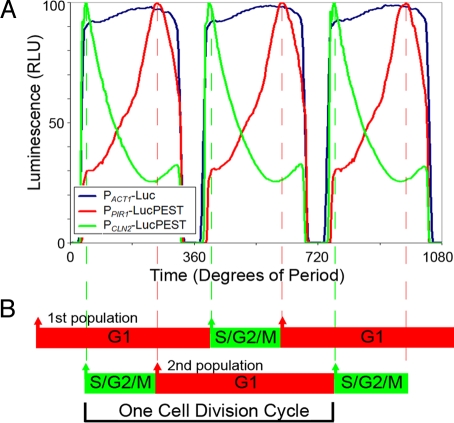

Different cell-cycle promoters can be used in conjunction with LucPEST to identify different CDC phases during the YROs. CLN2 is a gene that is maximally expressed in late G1 phase just before transition to S (35) whereas PIR1 is a gene whose transcription peaks during the M to G1 transition (34). Therefore, the expression of these two genes occupies opposite ends of the G1 phase. When the promoters for these genes are fused to LucPEST (PCLN2-LucPEST and PPIR1-LucPEST) and integrated into CEN.PK, they produce two distinctly different expression patterns in continuous, oscillating cultures, revealing characteristic landmarks of the cell division cycle within the YROs (Fig. 4). In a separate analysis of the YROs using data drawn from analyzing population budding percentages and cell concentrations, we find that the YROs of CEN.PK yeast can be optimally modeled as two populations of cells that synchronously divide 180° out of phase with one another, one CDC occurring every 2 YROs (CCS and EB, unpublished results). Our data with luminescence reporters (and bud index, Fig. 2) are consistent with the “two antiphase populations“ model. Fig. 4 shows that each population's short S/G2/M phase is roughly centered in the middle of the other population's long G1 phase and that the hypoxic mask occurs during a time when both populations are in G1 phase (see Fig. S4 for correction of the hypoxic mask and deconvolution of the two populations). These two reporters (and the cell cycle transitions they delineate) demonstrate that for each population during the YROs, G1 occupies ≈70% of the cell cycle and S/G2/M occupies ≈30%.

Fig. 4.

Luminescent reporters driven from 3 different promoters in continuous cultures show distinctly different patterns of expression over the YRO. (A) Peak luminescence from three separate cultures, each expressing a Luc reporter for a different promoter (each trace was normalized to 100 RLU for comparison). Three YRO cycles (which comprise 1.5 cell divisions for a single cell) are graphed. The peak of PCLN2-LucPEST luminescence (green) corresponds with exit from G1 and entrance into S phase of the CDC. The peak of PPIR1-LucPEST luminescence (red) corresponds with exit from M phase and entrance into G1. Luminescence from PACT1-Luc (blue) indicates intervals of relative hypoxia. (360° = 3.75 h in this experiment.) (B) Two populations of cells occupy the culture and their positions in the CDC are diagramed relative to the time axis of A and to each other (see Fig. S4 for a deconvolution of the two populations). Transitions between G1 and S/G2/M were determined from the peaks of the luminescence profile from A (vertical dashed red and green lines). The time of one predicted cell division is indicated by the black bracket.

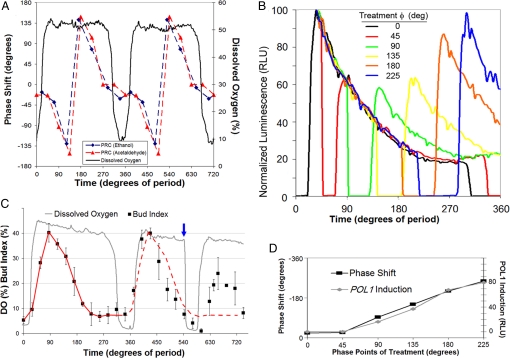

Acetaldehyde and ethanol may serve as synchronizing agents for oscillating respiration in continuous cultures because they are rhythmically released from yeast cells and they can strongly reset the phase of the YROs (19, 31). We wanted to know whether these phase altering substances also alter the timing of cell division associated with the YROs. Phase-response curves (PRCs) to injections of 1 mM acetaldehyde or 1 mM ethanol into oscillating cultures of CEN.PK/PPOL1-LucPEST were measured with regard to the DO oscillation (Fig. S5). Fig. 5A shows that both stimuli induce strong Type 0 resetting (2, 31). Independent of the phase of injection, either acetaldehyde or ethanol produces an immediate, but temporary, depletion of O2 in the culture as the metabolite is consumed (Fig. 5B and Fig. S5), whereas the resuming DO rhythm displays phase-dependent shifts (Fig. 5 A and D, and Fig. S5). For example, injection at phases between 0°–45° and 270°–405° have small effects on phase; injections between 45°–135° cause increasingly larger phase delays and injections between 180°–270° cause progressively smaller phase advances (Figs. 5 A and S5).

Fig. 5.

Phase responses of the YRO to 1 mM acetaldehyde or 1 mM ethanol. (A) A double-plotted phase-response curve (PRC) to ethanol (blue) or acetaldehyde (red) relative to a DO oscillation. Phase shifts are plotted in degrees of period with advance shifts plotted as positive values and delay shifts as negative values (see Fig. S5 for raw data that illustrate the method of calculation). (360° = 4.0 h for the acetaldehyde PRC experiment and 3.75 h for the ethanol PRC experiment.) (B) Luminescence responses of the PPOL1-LucPEST reporter to acetaldehyde treatments at the indicated phase points. The peak luminescence for each oscillation during which an acetaldehyde injection was made was normalized to 100 RLU and aligned with the peak of the 0° treatment. Treatments at phases 0° or 45° showed virtually no difference in luminescence aside from a brief hypoxic mask. Treatments made after phase 45° showed progressively increasing levels of PPOL1-LucPEST luminescence rebounding from the hypoxic mask as compared with the controls without treatment. (C) Bud index in response to 1 mM acetaldehyde injection made at phase 540° of the YRO (blue arrow). Bud index is the mean of 3–6 samples at each time point of >100 cells per sample (± SD.). The red line is the bud index trend from 0–360°; the dotted red line projects this trend onto the next period. (D) A strong correlation between the amount of rebounding POL1 induction after treatment and the magnitude of phase shift caused by the treatment. For comparison to luminescence, the phase shift in panel D is plotted on a monotonic 0° to −360° scale rather than the −180° to + 180° scale of A.

To ascertain CDC activity during the phase resetting experiment, luminescence from PPOL1-LucPEST was recorded after perturbations with acetaldehyde or ethanol. The data for acetaldehyde are summarized in Fig. 5B by showing the reporter's initial response to acetaldehyde over a full cycle of 360° (data for ethanol are similar but are not shown). The normalized luminescence traces for each of the acetaldehyde injections after the 0° injection were aligned with the peak of the 0° injection for comparison. The initial trend and shape of all of the luminescent PPOL1-LucPEST traces are virtually the same before injection, denoted in Fig. 5B by the group of multicolored lines following the same decay pattern after their peak. For traces of injections after 0°, a noticeable hypoxic mask occurs soon after injection followed by a return of the signal. Interestingly, when the signal returns from the hypoxic mask of the early treatments at 0° or 45° (black and red traces), the luminescence signal returns to the same level that it would have attained if no injection had occurred, indicated by the red trace rejoining the trend of the black and multicolored traces; these are the same phases at which practically no resetting of the YROs occurs (Fig. 5 A and D). However, as injections occurred progressively later in the cycle [e.g., at 90° (green), 135° (yellow), etc.], the luminescence signal rebounded to a significantly higher level than in the no-injection controls.

These results implied that some cells enter premature replication as a result of acetaldehyde/ethanol injections. If this were true, the percentage of budded cells in the culture should increase shortly after an injection. We confirmed this prediction by examining samples across two cycles of YROs in which acetaldehyde was injected at phase 540° [the first cycle in Fig. 5C (0–360°) serves as an unperturbed control]. After the injection, ≈25% of the culture prematurely budded (Fig. 5C), as predicted by the LucPEST data of Fig. 5B. The data in Fig. 5 A–C suggest a clear correlation between phases at which the acetaldehyde/ethanol stimulate new rounds of the CDC and phase shifts of the DO oscillation (Fig. 5D).

Some researchers have concluded that YROs may be the result of an endogenous self-sustained ultradian oscillator that functions analogously to the longer period circadian oscillators that regulate many cellular events, including cell division (18, 20, 30). That conclusion is based at least in part on yeast strains and conditions that exhibit YROs that cycle with periods as short as 40 m, and may reflect different underlying mechanisms than the ones investigated in this study. With our strains and conditions, a YRO has a period of 4–5 h [as reported by other investigators (20, 21, 26)]. Under the latter conditions, the data support an alternative hypothesis, namely that there are two populations of dividing cells in antiphase whose CDC rate and G1 duration are constrained by the dilution rate of the continuous culture environment (36) so that the CDC and YROs appear to be linked (22). We hypothesize that one population signals to the other its position in the cell cycle through nonfermentable metabolites, like acetaldehyde and ethanol, or possibly the hypoxia that results from their consumption. As a result, a YRO is the product of a balanced population structure and environmental signaling under our continuous culture conditions.

Responses to phase-shifting substances/signals disclose important clues to the mechanism of the oscillation itself. For example, do these substances synchronize cells in the population, thereby sustaining a robust oscillation in the presence of noise? Acetaldehyde and ethanol are potential YRO-synchronizing signals (19, 31) and their resetting efficacy is phase-dependent (Fig. 5). Moreover, this phase shifting is correlated with premature induction of cell division during the oscillation, thereby initiating new cell division and thus resetting the CDC's “timer.” Very late in the oscillation (e.g., 270°–315°), introduction of the potential signal has little effect on the phase of YROs and this correlates with the phase in the natural state of the system at which cells are secreting the greatest amount of nonfermentable carbon compounds into the medium (20, 21). We hypothesize that during the early phases of YROs (e.g., 0°–45°, immediately after the secretion of carbon compounds), cells that could have responded to the endogenous signal have done so and have committed to cell division, entering a fermentation-preferring state (Fig. S6). Therefore, the culture is deprived of “signal sensitive” cells that are capable of responding to new signal. Only the few straggling cells that narrowly missed the commitment to cell division and have since matured in the intervening time are potentially responsive to an injection of acetaldehyde or ethanol. If left unperturbed, increasing numbers of cells become capable of committing to cell division because of acquisition of required storage carbohydrates, and concomitantly become responsive to signals such as acetaldehyde or ethanol (and/or currently unidentified signals?). Premature injection of ethanol or acetaldehyde into the culture later in the YROs causes drastically larger phase delays because it interrupts the accrual of replication-competent cells, spurs early cell division, and thus desensitizes that group to the next endogenous signal that occurs. Missing this endogenous signal causes a delay. Afterward, the prematurely induced population produces its own endogenous signal and continues the cycle from that phase.

The principles and mechanisms upon which YROs depend are likely to have biological relevance in nature, for example, in colonies or dense films of yeast on substrates such as grapes. With the aid of luminescent reporters of gene regulation and metabolism such as the ones described here, future investigations will hopefully reveal evidence of cell–cell signaling and environmentally regulated cell division synchrony. We show here that the use of luminescence reporters for real-time measurements of promoter activity allow noninvasive measurement of yeast CDC events in both batch and continuous cultures. This reporter system also uncovered a linkage in our culture conditions between resetting the phase of the YRO and the induction of new rounds of cell division. The precision and ease of continuous monitoring of CDC-regulated promoter activity is just one example of the utility of this system. The reporting system presented here does have limitations; for example, the necessity for O2 restricts Luc's ability to report under hypoxic conditions. However, we take advantage of this apparent limitation to develop a reporter that accurately monitors the episodes of hypoxia that recur during YROs. Additionally, the 35-min half-life of LucPEST restricts its usefulness for investigating shorter-period (e.g., 40 min) metabolic oscillations such as those described from the strain IFO 0233 (18, 27, 30, 31). Nevertheless, further refinements of Luc (e.g., codon optimization and/or additional degradation signals) may enable the reporting of shorter-period oscillations. We envision the application of luminescent reporters in yeast to the assay of rapidly changing gene expression, in vivo oxygen monitoring, and further investigation of yeast rhythms.

Materials and Methods

Complete methods, including Table S1, are described in the SI Materials and Methods.

Bioluminescent Reporter Construction.

The coding region of firefly Luc from pGL3-Basic (Promega) was modified by adding a destabilizing PEST sequence from S. cerevisiae CLN2 and the terminator from ADH1. Various promoters of interest were cloned into a customized MCS and the reporter constructs were introduced into S. cerevisiae on various yeast expression vectors (pRS314, pRS315, pRS303, and pRS306).

Luciferase Reporter Stability Assay.

Cultures of strain SEY 6210 (MATα leu2 ura3 his3 trpl lys2 suc2) containing either the PGAL1-Luc or PGAL1-LucPEST reporter were inoculated in minimal media containing 2% raffinose and 50 μM beetle luciferin (Promega). They were grown at 28°C with agitation for the duration of this experiment. At time −60 min, Luc biosynthesis was induced with 2% galactose. Luminescence measurements were taken every 20 min until time 0. At time 0, Luc biosynthesis was repressed by 1.75% glucose and 9 μg/ml cycloheximide. Bioluminescent measurements were taken periodically 2 h after repression.

Cell Cycle Synchronization of LHY3865.

From a dense, YPD culture of strain LHY3865 (MATα ura3 leu2 bar1) (provided by L. Breeden, University of Washington, Seattle) containing the integrated PPOL1-LucPEST reporter, 250 μl were diluted into 100 ml of YPD (initial OD600 = 0.05). The culture was grown at 28°C with agitation until OD600 = 0.18. Ten milliliters of this culture were moved to a 50-ml flask and treated with 15 μM α-factor (BioChemika 63591) and incubated for 3 h at 28°C with agitation. α-factor-treated cells were collected and washed 3× with 10 ml of conditioned media containing 15 μg/ml proteinase E (Sigma P-6911) and 50 μM beetle luciferin (Promega E1602). The final washed pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of conditioned media and moved to a 50-ml magnetically stirred flask. Bioluminescence from the Luc reporter was monitored continuously by a Hamamatsu HC135–01 photomultiplier. One hundred microliter samples were collected from the culture and frozen every 10 min for 3 h to determine changes in the bud index over time.

Monitoring Luminescence and Respiratory Oscillations.

CEN.PK113–7D (MATá) (provided by Dr. Peter Kötter, University of Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany) was integrated with luminescent reporters. A 850-ml culture was grown in a 3-L New Brunswick Scientific Bioflow 110 reactor operated at 550 rpm agitation, 900 ml/min air flow, 30°C, at pH 3.4. The culture was grown in batch until it starved and then for another 4–12 h before beginning continuous culture with the media described in the SI Materials and Methods at a dilution rate of 0.08–0.09 per hour. Once oscillations began, 5 μM beetle luciferin (Gold Biotech) was injected into the culture during the hypoxic phase of an oscillation, and then maintained in the culture at this concentration either through the feeding media or by steady drip from a syringe pump. Luminescence from the continuous culture was constantly recorded by running a closed loop of culture in transparent tubing from the culture vessel into a dark box in front of a HC135–01 photomultiplier, and then back into the vessel (Fig. S7).

Extract Preparation and Immunoblotting.

Cells from 15-ml samples were periodically collected from the continuous culture effluent, centrifuged, and frozen. Samples were lysed on a MP Bio FastPrep-24 and total protein from the lysate was collected. Immunoblotting was performed on 10 μg of total protein per sample. The antibodies and concentrations used are as follows: 1:2,000 polyclonal anti-luciferase (Sigma L0159) was detected with 1:4,000 donkey anti-rabbit IgG HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Promega W401B). Polyclonal antiyeast actin 1:2,000 (Santa Cruz 1615) was detected with 1:10,000 donkey anti-goat HRP conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz 2020).

Phase Shifting.

An oscillating culture of CEN.PK113–7D with the integrated PPOL1-LucPEST reporter was allowed to establish a stable periodicity and monitored for at least 4 cycles before injection. Eight hundred fifty μl of either 1 M acetaldehyde or 1 M ethanol was injected into the culture at phases 0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, 180°, 225°, 270°, and 315°, allowing at least three cycles between injections. Phase 0° was defined as the time when DO started to rise from hypoxia. Phase shifts were determined by measuring the difference between the trough of the DO oscillation in the cycle immediately after the injection (the abrupt hypoxic response to the injection was ignored) and the time of the expected DO trough if the injection had not been administered (based on the average period from the three cycles before injection; Fig. S5).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We dedicate this paper to the memory of Dr. Robert Klevecz, a scientific pioneer of the YRO who generously tutored us in the lore of obtaining robust respiratory oscillations from yeast. We thank Dr. Kathy Friedman for use of reagents and equipment, Drs. Robert Klevecz and Caroline Li for helping us to configure our culture apparatus to achieve reproducible respiratory oscillations, Dr. Peter Kötter for the CEN.PK113–7D strain, and Dr. Linda Breeden for the LHY3865 strain. This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant NIGMS R01 067152 (to C.H.J.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0809482105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Alon U. An Introduction to Systems Biology – Design Principles of Biological Circuits. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunlap JC, Loros JJ, DeCoursey PJ. Chronobiology: Biological Timekeeping. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandes C, et al. Novel features of Drosophila period Transcription revealed by real-time luciferase reporting. Neuron. 1996;16:687–692. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hastings JW, Johnson CH. In: Methods in Enzymology; Biophotonics. Mariott AG, Parker I, editors. San Diego: Academic; 2003. pp. 75–104. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kondo T, et al. Circadian rhythms in prokaryotes: Luciferase as a reporter of circadian gene expression in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5672–5676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millar AJ, Short SR, Chua NH, Kay SA. A novel circadian phenotype based on firefly luciferase expression in transgenic plants. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1075–1087. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.9.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamazaki S, et al. Resetting central and peripheral circadian oscillators in transgenic rats. Science. 2000;288:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kondo T, et al. Circadian clock mutants of cyanobacteria. Science. 1994;266:1233–1236. doi: 10.1126/science.7973706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millar AJ, Carré IA, Strayer CA, Chua NH, Kay SA. Circadian clock mutants in Arabidopsis identified by luciferase imaging. Science. 1995;267:1161–1163. doi: 10.1126/science.7855595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, et al. Circadian orchestration of gene expression in cyanobacteria. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1469–1478. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michael TP, McClung CR. Enhancer trapping reveals widespread circadian clock transcriptional control in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:629–639. doi: 10.1104/pp.021006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gooch VD, et al. Fully codon-optimized luciferase uncovers novel temperature characteristics of the Neurospora clock. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:28–37. doi: 10.1128/EC.00257-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Izumo M, Sato TR, Straume M, Johnson CH. Quantitative analyses of circadian gene expression in mammalian cell cultures. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mateus C, Avery SV. Destabilized green fluorescent protein for monitoring dynamic changes in yeast gene expression with flow cytometry. Yeast. 2000;16:1313–1323. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(200010)16:14<1313::AID-YEA626>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson JF, Hayes LS, Lloyd DB. Modulation of firefly luciferase stability and impact on studies of gene regulation. Gene. 1991;103:171–177. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90270-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huh W-K, et al. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Von Meyenburg K. Energetics of the budding cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during glucose limited aerobic growth. Arch Microbiol. 1969;66:289–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00414585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klevecz RR, Bolen J, Forrest G, Murray DB. A genomewide oscillation in transcription gates DNA replication and cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1200–1205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306490101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martigani E, Porro D, Ranzi BM, Alberghina L. Involvement of a cell size control mechanism in the induction and maintenance of oscillations in continuous cultures of budding yeast. Biotechnol Bioengin. 1990;36:453–459. doi: 10.1002/bit.260360504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tu BP, Kudlicki A, Rowicka M, McKnight SL. Logic of the yeast metabolic cycle: Temporal compartmentalization of cellular processes. Science. 2005;310:1152–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.1120499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu Z, Tsurugi K. A potential mechanism of energy-metabolism oscillations in an aerobic chemostat culture of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS J. 2006;273:1696–1709. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porro D, Martegani E, Ranzi BM, Alberghina L. Oscillations in continuous cultures of budding yeast: A segregated parameter analysis. Biotechnol Bioengineer. 1988;32:411–417. doi: 10.1002/bit.260320402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lloyd D. The ultradian clock: Not to be confused with the cell cycle. Nat Rev Molec Cell Biol. 2006;Vol. 7 Dec. Online Correspondence. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tu BP, Kudlicki A, Rowicka M, McKnight SL. Let the data speak. Nat Rev Molec Cell Biol. 2006;Vol. 7 Dec. Online Correspondence. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asai M, et al. Visualization of mPer1 transcription in vitro: NMDA induces a rapid phase shift of mPer1 gene in cultured SCN. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1524–1527. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00445-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beuse M, Bartling R, Kopmann A, Diekmann H, Thoma M. Effect of dilution rate on the mode of oscillation in continuous cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biotech. 1998;61:15–31. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(98)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Satroutdinov AD, Kuriyama H, Kobayashi H. Oscillatory metabolism of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in continuous culture. FEMS Microbiol Let. 1992;98:261–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90167-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plevani P, et al. The yeast DNA polymerase-primase complex: Genes and proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;951:268–273. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(88)90096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verma R, Patapoutian A, Gordon CB, Campbell JL. Identification and purification of a factor that binds to the Mlu I cell cycle box of yeast DNA replication genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7155–7159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray DB, Roller S, Kuriyama H, Lloyd D. Clock control of ultradian respiratory oscillation found during yeast continuous culture. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:7253–7259. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7253-7259.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray DB, Klevecz RR, Lloyd D. Generation and maintenance of synchrony in Saccharomyces cerevisiae continuous culture. Exp Cell Res. 2003;287:10–15. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hastings JW, McElroy WD, Coulombre J. The effect of oxygen upon the immobilization reaction in firefly luminescence. J Cell Physiol. 1953;42:137–150. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030420109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moriyama EH, et al. The influence of hypoxia on bioluminescence in luciferase-transfected gliosarcoma tumor cells in vitro. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2008;6:675–680. doi: 10.1039/b719231b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spellman PT, et al. Comprehensive identification of cell cycle-regulated genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by microarray hybridization. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3273–3297. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wittenberg C, Sugimoto K, Reed SI. G1-specific cyclins of S. cerevisiae: Cell cycle periodicity, regulation by mating pheromone, and association with the p34CDC28 protein kinase. Cell. 1990;62:225–237. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90361-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brauer MJ, et al. Coordination of growth rate, cell cycle, stress response, and metabolic activity in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:352–367. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.