Abstract

A high-glycemic index (GI) diet has been shown to increase adiposity in rodents; however, the long-term metabolic effects of a low- and high-GI diet have not been examined. In this study, a total of 48 male 129SvPas mice were fed diets high in either rapidly absorbed carbohydrate (RAC; high GI) or slowly absorbed carbohydrate (SAC; low GI) for up to 40 wk. Diets were controlled for macronutrient and micronutrient content, differing only in starch type. Body composition and insulin sensitivity were measured longitudinally by DEXA scan and oral glucose tolerance test, respectively. Food intake, respiratory quotient, physical activity, and energy expenditure were assessed using metabolic cages. Despite having similar mean body weights, mice fed the RAC diet had 40% greater body fat by the end of the study and a mean 2.2-fold greater insulin resistance compared with mice fed the SAC diet. Respiratory quotient was higher in the RAC group, indicating comparatively less fat oxidation. Although no differences in energy expenditure were observed throughout the study, total physical activity was 45% higher for the SAC-fed mice after 38 wk of feeding. We conclude that, in this animal model, 1) the effect of GI on body composition is mediated by changes in substrate oxidation, not energy intake; 2) a high-GI diet causes insulin resistance; and 3) dietary composition can affect physical activity level.

Keywords: carbohydrates, energy expenditure, respiratory quotient, insulin resistance, substrate oxidation

in recent decades, dietary patterns in the united states have shifted toward an increased intake of refined carbohydrate (9). This shift has paralleled a rise in the prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes, and epidemiological studies have demonstrated associations between carbohydrate type and body weight, adiposity, or associated cardiovascular risk factors (10, 13, 20, 21, 32). Many, but not all, studies have shown that diets low in glycemic index (GI) or glycemic load (GL) have beneficial effects on weight loss and/or reduction of risk factors for chronic disease in humans (2, 6, 12–14, 18, 23, 24, 28). In two energy-restricted feeding studies, resting energy expenditure (EE) declined to a lesser extent among overweight individuals consuming lower-GL/higher-fat vs. higher-GL/lower-fat diets (1, 18).

The effects of GI on sports performance have been examined in numerous small clinical trials. Low- vs. high-GI meals were shown in some studies to enhance fat utilization during sustained physical activity (PA), improve peak performance, and increase endurance (8, 27, 29, 30, 33–36). A question not explored by these studies is whether GI might affect spontaneous PA level.

In relatively short-term nutrient-controlled rodent studies, treatment with a high-GI diet resulted in increased adiposity, altered glucose homeostasis, and evidence of greater metabolic efficiency (11, 16, 17, 22). However, the sequence of physiological events relating GI to body composition and energy metabolism remains incompletely examined and the subject of controversy (4). The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of GI on adiposity, glucose homeostasis, substrate oxidation, EE, and PA in an animal model in which confounding dietary and environmental factors can be controlled over the long term.

RESEARCH METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Animals.

Parallel studies were performed in a total of 48 129SvPas mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) divided into three cohorts (n = 16 each). Changes in adiposity and insulin sensitivity were studied in cohort 1 over a 38-wk period, and assessment of energy metabolism and PA was performed at week 40 using metabolic cages. Energy metabolism and PA were assessed for 38 wk in cohort 2 and for 19 wk in cohort 3. This strain of mice was chosen because of its relative resistance to diet-induced obesity, allowing us to examine the physiological effects of diet, with less confounding by body weight differences.

For each cohort, 5-wk-old male mice were acclimated to the animal facility on standard chow for 2 days, after which they were individually housed and placed on a low-GI diet that was high in amylose, a slowly absorbed carbohydrate (SAC), for 1 wk. After this run-in period, mice were weight paired and randomized to either continue on the SAC diet or receive a high-GI diet that was high in amylopectin, a rapidly absorbed carbohydrate (RAC). Food and water were provided ad libitum throughout the study, and body weight was measured 3 times/wk. Mice were maintained on a 12:12-h dark-light cycle in standard housing, except when in metabolic cages. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Children's Hospital Boston (protocol no. A04-08-114).

Diets.

The two diets were of identical macronutrient composition (68% carbohydrate, 13% fat, 19% protein) and energy density (4.2 kcal/g, measured by bomb calorimetry; Table 1) and differed only in the starch component, which was 100% amylopectin for the RAC diet and 60% amylose-40% amylopectin for the SAC diet; both starches are naturally occurring in corn. The composition of these diets has previously been described in detail (22); in the current study, they were prepared in our laboratory, color-coded using nonnutritive lipid-soluble food coloring, and provided to the mice as powdered food in aluminum dishes (Table 1). Previous studies where postprandial glycemic response to the two diets was assessed demonstrated significantly greater area under the curve (AUC) for rats fed the RAC compared with the SAC diet (17). Glycemic response was replicated in crossover studies performed in 129SvPas mice that were separate from the current study [glucose AUC (RAC vs. SAC): 7,923 ± 1,651 vs. 5,627 ± 2,003, P = 0.049].

Table 1.

Dietary composition

| Components, g/kg | SAC Diet | RAC Diet |

|---|---|---|

| Starch | ||

| 60% amylose/40% amylopectina | 592 | |

| 100% Amylopectinb | 592 | |

| Caseinc | 200 | 200 |

| Sucrosed | 85 | 85 |

| Soybean oild | 56 | 56 |

| Mineral mixc | 35 | 35 |

| Gelatinc | 20 | 20 |

| Vitamin mixc | 10 | 10 |

| dl-methioninec | 2 | 2 |

| Dietary characteristics | ||

| Calculated energy density, kcal/ge | 4.19 | 4.19 |

| Measured energy density, kcal/gf | 4.15 | 4.20 |

SAC, slowly absorbed carbohydrate; RAC, rapidly absorbed carbohydrate;

Hi-Maize, National Starch and Chemical Company, Bridgewater, NJ;

C-Gel 03420, Cerestar USA, Hammond, IN;

Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN;

commercially available;

calculated from published nutrient databases;

measured by bomb calorimetry, mean of 2 dried samples.

Body composition.

Body composition was measured in nonfasted mice between 1:00 PM and 4:00 PM during the 1-wk run-in period and at indicated time points by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) using the Lunar PIXImus Mouse Densitometer (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI). Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (85 mg/kg) and xylazine (8.5 mg/kg) administered intraperitoneally. Additional ketamine, to a maximum of 100 mg/kg, was administered if a mouse did not respond to the initial dosage. If a mouse could not be fully anesthetized, the DEXA scan was omitted for that animal at that time point. Intramouse coefficients of variation were <5%.

Oral glucose tolerance tests and blood collection.

Oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) were performed beginning 2 wk after randomization and at indicated time-points. On test days, mice were placed in clean cages without food at 8:00 AM, and fasted blood was collected from the tip of the tail vein with the use of heparinized capillary tubes between 1:00 PM and 2:00 PM. Following oral gavage of 2 mg glucose/g body wt, blood was collected by tail bleed for measurement of blood glucose using the One Touch Ultra glucometer (Lifescan, Milpitas, CA) at 30, 60, and 120 min. Plasma collected at 30 and 120 min following glucose gavage was frozen at −80°C for further analyses. Plasma insulin was measured in batches using the rat insulin ELISA with mouse insulin as standard (Crystal Chem, Downers Grove, IL). The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 5.7 and 6.3%, respectively.

Metabolic cages.

Nonprotein respiratory quotient (RQ), food intake, EE, and PA were measured using the comprehensive laboratory animal monitoring system (CLAMS) from Columbus Instruments (Columbus, OH) in individual cages without bedding. Pilot studies in our laboratory (data not shown) and the Mouse Phenome Project at the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME; http://www.jax.org/phenome) have shown that mouse behavior is altered during the 1st day of exposure to the CLAMS cages. Therefore, mice were acclimated to the metabolic cages for 48 h prior to the start of data collection at all time points. This acclimation time also allowed for close monitoring of body weight and food and water intake and to ensure the animals' health. Data collection began at midday after 48 h of acclimation and continued uninterrupted for 48 h. Room temperature was maintained at 23°C during the CLAMS episodes on the basis of recommendations from the Mouse Phenome Project.

Oxygen consumption (V̇o2) and carbon dioxide expiration (V̇co2) were measured by indirect calorimetry, with an air flow of 0.6 l/min. RQ (V̇co2/V̇o2) data are presented as a 48-h average. EE was calculated using the equation kcal/h = [3.815 + 1.232 (V̇co2/V̇o2)] × V̇o2, based on the table of Lusk (15), and is presented as EE/48-h. Total PA and ambulatory (AMB) PA were measured continuously by light beam breaks in the two-dimensional horizontal plane; total PA represents all movement recorded, whereas AMB PA is a measurement of movement across the x- and y-axes. PA counts were summed for each 48-h CLAMS episode and for dark and light cycles, respectively.

Net energy intake.

Food intake was measured by the CLAMS to 0.01 g during the 48-h CLAMS episode and converted to total kilocalorie intake. Previous work in our laboratory has shown differential energy malabsorption, evidenced by increased fecal energy for the SAC-fed mice (22). For the SAC group, fecal energy density was assessed from 48-h fecal collections by bomb calorimetry at week 2 of feeding, as previously described (22). Pilot studies also showed that fecal energy density remains constant with long-term feeding in the SAC group. Thus, energy malabsorption was calculated for individual mice at each time point based on fecal energy data from week 2 and fecal output for each 48-h CLAMS episode. Because of the minimal malabsorption that occurs on the RAC diet, stool output of animals on this diet was much smaller, and we had technical difficulties collecting samples of adequate volume for analysis. For this reason, we used the value obtained from our prior study, 3.062 ± 0.103 kcal/g, in which animals of the same strain were fed the same RAC diet. Net energy intake was calculated for each time point by subtracting fecal energy from total energy intake.

Exclusion criteria.

During data collection in the CLAMS, if a mouse's percent weight loss exceeded the cohort's mean percent weight loss plus two standard deviations, all data for that mouse were excluded from the analyses at that time point. In total, four out of 48 mice were removed from the study early. One mouse was found dead from unknown causes at week 34, and three mice that developed severe dermatitis were removed at weeks 21, 27, and 30, respectively.

Statistical analyses.

Differences in body weight, body composition, net energy intake, plasma insulin, blood glucose, glucose AUC, insulin resistance, PA, and EE were assessed longitudinally using repeated-measures ANOVA (α = 0.05) with diet and time as factors. We did not collect baseline data for insulin. In the absence of this data point, ANOVA would inappropriately adjust for the difference that had occurred between groups after randomization and prior to the first available time point at week 14. Therefore, we analyzed insulin data by comparing the average of all available data by t-test. For RQ, we also compared the average of all available data by t-test because this end point appeared to change in varying ways throughout the study. For PA, the diet effect appeared to emerge over time, becoming greatest at the end of the study. Therefore, we used a t-test at weeks 38–40, including both cohorts, as a post hoc method to characterize this effect. According to an a priori power calculation, attaining statistical power of 0.80 (α = 0.05) required the inclusion of 16 mice/dietary group for the detection of diet-induced differences of 3,733 counts in PA and 0.44 kcal in EE. Because of necessary exclusions, our statistical power was reduced at some time points. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 for Windows, and data are presented as means ± SD.

RESULTS

Stool analysis, energy intake, and EE.

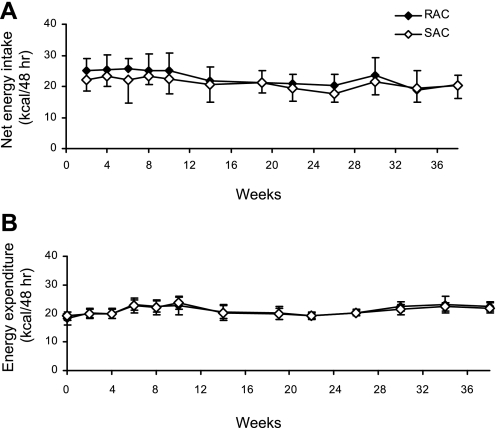

Consistent with findings of a prior study (22), SAC-fed animals showed a moderate degree of malabsorption, with stool energy density of 3.996 ± 0.074 kcal/g. Net ad libitum energy intake was measured over the course of 48 h in the CLAMS and did not differ between the SAC and RAC groups throughout the 38-wk study (Fig. 1A). No differences in energy intake between the SAC and RAC groups were observed for the dark and light periods, respectively, nor in terms of length or number of feeding bouts (data not shown). Both SAC and RAC mice expended ∼15% more energy during the dark vs. the light period (data not shown), but there was no effect of diet on 48-h EE (Fig. 1B) or EE during the dark and light periods throughout the study (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Net ad libitum energy intake and energy expenditure (EE) during the 48-h comprehensive laboratory animal monitoring system (CLAMS) measurements for the rapidly (RAC) and slowly absorbed carbohydrate (SAC) groups. A: net energy intake was calculated by subtracting fecal energy from total energy intake. B: total EE was measured by indirect calorimetry. Values are means ± SD, with 13–16 mice/dietary group at each time point for weeks 0–19 and 6–8 mice/dietary group at each time point for weeks 20–38. Repeated-measures ANOVA, diet × time effect was P = not significant (NS) for net energy intake and EE.

Body weight and composition.

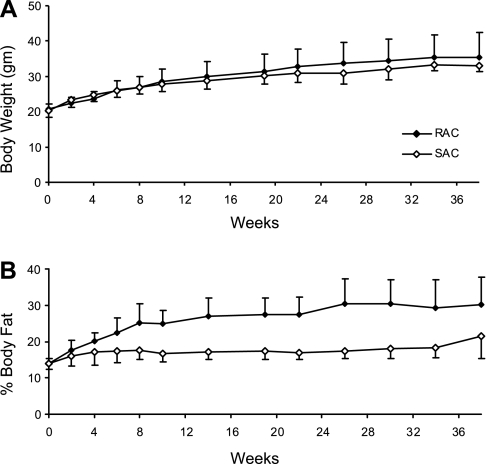

Body weight was collected for all 48 mice, and a representative graph is shown for cohort 1 (n = 16) in Fig. 2A. A diet × time effect was observed (P = 0.002). However, differences in body weight between groups were modest throughout the study and not significant at 38 wk (35.2 ± 7.3 g for RAC vs. 33.1 ± 1.4 g for SAC, P = 0.39). In contrast, body composition measured by DEXA at indicated time points was markedly different between groups throughout the study, as shown in Fig. 2B (diet × time effect, P < 0.0001). By week 38, percent body fat was 40% greater in the RAC vs. the SAC group (30.1 ± 7.6 vs. 21.5 ± 3.1%, P = 0.008). Results for body weight and body composition were similar for cohorts 2 and 3 (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Mean body weight and composition for the RAC and SAC groups throughout the study. Mean body weight (A) and %body fat (B) are presented. Values are means ± SD, with 5–8 mice/group at each time point. Repeated-measures ANOVA, diet × time effect was P = 0.002 for body weight and P < 0.0001 for %body fat.

RQ.

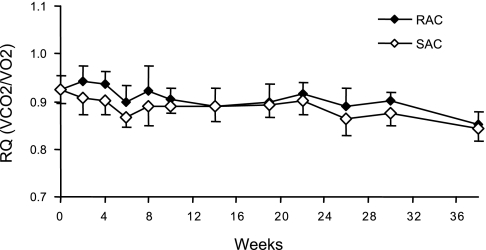

Mean RQ was higher for the RAC vs. SAC group (0.91 ± 0.02 vs. 0.89 ± 0.01, P = 0.0002; Fig. 3). The difference between groups was most pronounced for the first 8 wk following randomization.

Fig. 3.

Mean respiratory quotient (RQ) for RAC and SAC groups throughout the study. All mice were fed the SAC diet for a 1-wk run-in period (week 0) followed by randomization to either the RAC or SAC diet. Each time point represents a 48-h measurement. Data are means ± SD with 13–16 mice/dietary group at each time point for weeks 0–19 and 6–8 mice/dietary group at each time point for weeks 20–38. Values, averaged across all time points, were significantly different between the RAC and SAC groups by t-test (0.91 ± 0.02 vs. 0.89 ± 0.01, P = 0.0002, respectively). V̇co2, carbon dioxide expiration; V̇o2, oxygen consumption.

Glucose homeostasis.

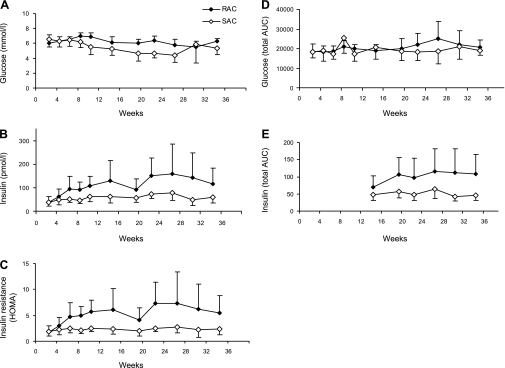

Fasted blood glucose and plasma insulin were significantly higher for the RAC group compared with the SAC group (6.2 ± 0.5 vs. 5.4 ± 0.9 mmol/l, P = 0.0003, and 114.5 ± 68.0 vs. 58.8 ± 22.7 pmol/l, P = 0.03, respectively; Fig. 4, A and B). Insulin resistance, as calculated by homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) index [(fasting insulin × fasting glucose)/22.5] (37), was 2.2-fold higher for the RAC vs. SAC group (5.4 ± 3.4 vs. 2.4 ± 1.1, P = 0.02) (Fig. 4C). Although there was no difference in glycemic AUC following OGTT (Fig. 4D), mean total insulin AUC was higher for the RAC vs. SAC group (108 ± 48 and 48 ± 11, P = 0.02; Fig. 4E). Insulin at 30 min, a time point of particular interest as a measurement of insulin secretion (27), was different between groups (P = 0.04). Results from OGTT at week 20 in cohort 2 were similar for both glucose and insulin response (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Assessment of insulin sensitivity by oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) for RAC and SAC groups. Data for fasting blood glucose (P = 0.0003; A), fasting plasma insulin (P = 0.03; B), insulin resistance calculated by HOMA (P = 0.02; C), glucose area under the curve (AUC) during OGTT (P = 0.14; D), and insulin AUC during OGTT (P = 0.02; E). Values are means ± SD; n = 4–8/group at each time point. A–D: repeated-measures ANOVA (diet × time effect). E: mean values were averaged across all time points after randomization and compared by Student's t-test.

PA.

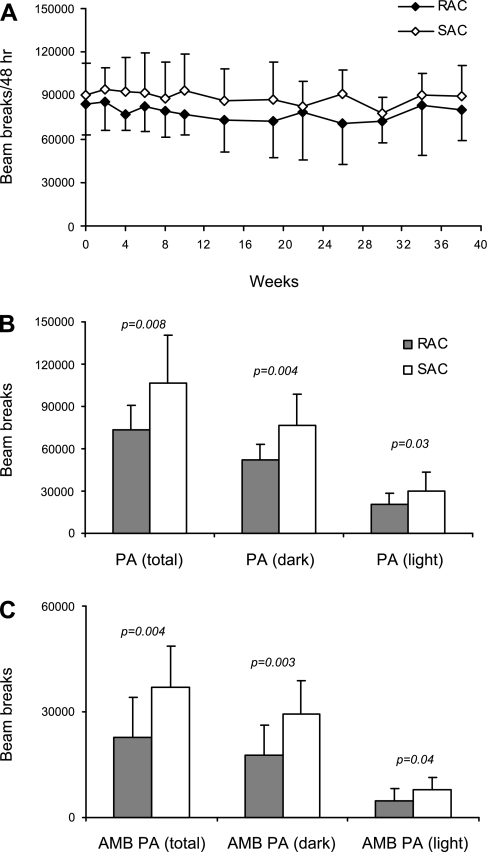

Total PA was nonsignificantly higher (by 15%) for the SAC group compared with the RAC group when observed as total counts/48 h (Fig. 5A). Results for AMB PA were similar (data not shown). At weeks 38–40, both total PA (106,347 ± 34,212 vs. 73,547 ± 17,447, P = 0.008) and AMB PA (36,991 ± 11,628 vs. 22,725 ± 11,432, P = 0.004) were significantly greater for the SAC than the RAC group (Fig. 5, B and C).

Fig. 5.

Physical activity (PA) during the 48-h CLAMS measurements for RAC and SAC groups. A: total PA is represented as total light beam breaks within 48 h. Values are means ± SD, with 13–16 mice/dietary group at each time point for weeks 0–19 and 6–8 mice/dietary group at each time point for weeks 20–38. Repeated-measures ANOVA, diet × time effect was P = NS. B and C: data for total PA and ambulatory (AMB) PA after 38–40 wk of feeding are shown. Values are means ± SD, with 12–15 mice/dietary group. Student's t-test. P values are indicated.

DISCUSSION

Prior research aiming to establish a relationship between GI and energy metabolism has been inconclusive, and a consensus as to whether GI directly affects substrate oxidation or energy expenditure remains elusive (4). The purpose of this study was to examine the longitudinal changes in obesity-related parameters among rodents fed diets differing in GI but controlled for macro- and micronutrients. We found that the RAC vs. SAC group had lower fat oxidation, 40% greater body fat, and 2.2-fold greater insulin resistance, although net energy intake did not differ between groups. Of particular interest, the RAC group became less physically active than those fed the SAC diet.

The postprandial hyperglycemia on a high-GI diet increases insulin secretion, and higher insulin levels would promote glucose uptake in insulin-sensitive tissues and inhibit lipolysis in adipose tissue. These metabolic events would acutely favor oxidation of carbohydrate rather than fat and chronically lead to accumulation of body fat. The higher RQ in mice fed the RAC diet, especially during the initial weeks of treatment before development of more severe insulin resistance, supports this possibility.

Higher levels of physical activity are characteristically associated with greater lean body mass, a lower RQ (indicating an increased capacity to oxidize fat), and enhanced insulin sensitivity (3, 7, 19, 25, 26, 38), all characteristics observed in the SAC-fed mice. Moreover, physical activity, by virtue of its effect on energy balance, tends to promote loss of body fat. However, the question of whether dietary composition in general, and carbohydrate type in particular, might affect physical activity has not been extensively evaluated. Indeed, attempts to study such phenomena in humans over the long term would likely be confounded by numerous dietary and environmental factors. The tendency of the SAC-fed mice to be more active throughout the study and the significantly increased physical activity level at the end of the study suggest a novel mechanism whereby diet may produce fat loss. The reasons for this difference in physical activity may relate to improved access to metabolic fuels or maintenance of greater lean mass on a low- vs. high-GI diet, although these possibilities remain speculative.

Three study limitations warrant this consideration. First, substrate oxidation and energy expenditure were assessed by indirect calorimetry, which relies upon established relationships between oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide expiration. Since we did not measure urinary nitrogen excretion, we cannot determine to what degree the higher RQ on the RAC diet might have been caused by higher rates of protein oxidation (although we would presume that this contribution would be relatively small, given the low protein to carbohydrate content of the diets). Second, the resistant starch content of the SAC diet was higher than that of the RAC diet. Resistant starch is carbohydrate that escapes digestion in the small intestine, thereby altering the colonic environment due to increased fermentation, subsequently influencing microbial flora composition and free fatty acid production (31). Whether these events could importantly affect fuel partitioning and energy metabolism has not been established. Recently, differences in colonic bacteria have been documented in lean and obese humans and animals (5). These differences may play a causal role in obesity through novel mechanisms such as direct effects on fat cell metabolism. Thus, it is possible that the physiological effects of the diets were mediated not only by actions in the small intestine but also by actions in the large intestine. To examine this issue, further studies employing isotopic tracers would be required. Third, the degree to which these findings apply to humans remains speculative. Humans tend to have lower rates of de novo lipogenesis than rodents, a biological difference that might attenuate the effects of diet on body composition.

In conclusion, this study illustrates that the rate of carbohydrate digestion influences substrate oxidation, body composition, and insulin sensitivity independent of net energy intake, nutrient composition, and other confounding factors. Our findings further suggest that a low-GI diet could increase spontaneous physical activity level, a possibility that might have important implications for the prevention and treatment of obesity and promotion of physical fitness.

GRANTS

This work was funded by a grant from the Charles H. Hood Foundation, the Timothy Murphy Fund, and discretionary funds from the Department of Medicine, Children's Hospital Boston. K. Scribner was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Training Grant T32-DK-07699. D. S. Ludwig is supported in part by a grant from the New Balance Foundation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ruth M. Diedrichsen at the University of Nebraska for performing the bomb calorimetry, National Starch and Chemical for generously providing the high-amylose starch, and Jason Rightmyer at Children's Hospital Boston for assistance with data management.

Present address of K. B. Scribner: ALPCO Diagnostics, 26-G Keewaydin Dr., Salem, NH 03079.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agus MS, Swain JF, Larson CL, Eckert EA, Ludwig DS. Dietary composition and physiologic adaptations to energy restriction. Am J Clin Nutr 71: 901–907, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouche C, Rizkalla SW, Luo J, Vidal H, Veronese A, Pacher N, Fouquet C, Lang V, Slama G. Five-week, low-glycemic index diet decreases total fat mass and improves plasma lipid profile in moderately overweight nondiabetic men. Diabetes Care 25: 822–828, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng YJ, Gregg EW, De Rekeneire N, Williams DE, Imperatore G, Caspersen CJ, Kahn HS. Muscle-strengthening activity and its association with insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 30: 2264–2270, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diaz EO, Galgani JE, Aguirre CA. Glycaemic index effects on fuel partitioning in humans. Obes Rev 7: 219–226, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiBaise JK, Zhang H, Crowell MD, Krajmalnik-Brown R, Decker GA, Rittmann BE. Gut microbiota and its possible relationship with obesity. Mayo Clin Proc 83: 460–469, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebbeling CE, Leidig MM, Sinclair KB, Hangen JP, Ludwig DS. A reduced glycemic load diet in the treatment of adolescent obesity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 157: 773–779, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekelund U, Franks PW, Sharp S, Brage S, Wareham NJ. Increase in physical activity energy expenditure is associated with reduced metabolic risk independent of change in fatness and fitness. Diabetes Care 30: 2101–2106, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Febbraio MA, Keenan J, Angus DJ, Campbell SE, Garnham AP. Preexercise carbohydrate ingestion, glucose kinetics, and muscle glycogen use: effect of the glycemic index. J Appl Physiol 89: 1845–1851, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Grodstein F, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Willett WC. Trends in the incidence of coronary heart disease and changes in diet and lifestyle in women. N Engl J Med 343: 530–537, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu Y, Block G, Norkus EP, Morrow JD, Dietrich M, Hudes M. Relations of glycemic index and glycemic load with plasma oxidative stress markers. Am J Clin Nutr 84: 70–76, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kabir M, Rizkalla SW, Champ M, Luo J, Boillot J, Bruzzo F, Slama G. Dietary amylose-amylopectin starch content affects glucose and lipid metabolism in adipocytes of normal and diabetic rats. J Nutr 128: 35–43, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludwig DS The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA 287: 2414–2423, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma Y, Olendzki B, Chiriboga D, Hebert JR, Li Y, Li W, Campbell M, Gendreau K, Ockene IS. Association between dietary carbohydrate and body weight. Am J Epidemiol 161: 359–367, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maki KC, Rains TM, Kaden VN, Raneri KR, Davidson MH. Effects of a reduced-glycemic-load diet on body weight, body composition, and cardiovascular disease risk markers in overweight and obese adults. Am J Clin Nutr 85: 724–734, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLean JA, Tobin G. Animal and Human Calorimetry. New York: Cambridge University, 1987.

- 16.Pawlak DB, Bryson JM, Denyer GS, Brand-Miller JC. High glycemic index starch promotes hypersecretion of insulin and higher body fat without affecting insulin sensitivity. J Nutr 131: 99–104, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pawlak DB, Kushner JA, Ludwig DS. Effects of dietary glycaemic index on adiposity, glucose homeostasis, and plasma lipids in animals. Lancet 364: 778–785, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira MA, Swain J, Goldfine AB, Rifai N, Ludwig DS. Effects of a low-glycemic load diet on resting energy expenditure and heart disease risk factors during weight loss. JAMA 292: 2482–2490, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravussin E, Swinburn BA. Metabolic predictors of obesity: cross-sectional versus longitudinal data. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 17, Suppl 3: S28–S31, discussion S41–S42, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salmerón J, Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Spiegelman D, Jenkins DJ, Stampfer MJ, Wing AL, Willett WC. Dietary fiber, glycemic load, and risk of NIDDM in men. Diabetes Care 20: 545–550, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salmerón J, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Wing AL, Willett WC. Dietary fiber, glycemic load, and risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA 277: 472–477, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scribner KB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Hepatic steatosis and increased adiposity in mice consuming rapidly vs. slowly absorbed carbohydrate. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15: 2190–2199, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slabber M, Barnard HC, Kuyl JM, Dannhauser A, Schall R. Effects of a low-insulin response, energy-restricted diet on weight loss and plasma insulin concentrations in hyperinsulinemic females. Am J Clin Nutr 60: 48–53, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sloth B, Krog-Mikkelsen I, Flint A, Tetens I, Björck I, Vinoy S, Elmståhl H, Astrup A, Lang V, Raben A. No difference in body weight decrease between a low-glycemic-index and a high-glycemic-index diet but reduced LDL cholesterol after 10-wk ad libitum intake of the low-glycemic-index diet. Am J Clin Nutr 80: 337–347, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snitker S, Le KY, Hager E, Caballero B, Black MM. Association of physical activity and body composition with insulin sensitivity in a community sample of adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161: 677–683, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snitker S, Tataranni PA, Ravussin E. Respiratory quotient is inversely associated with muscle sympathetic nerve activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 3977–3979, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sparks MJ, Selig SS, Febbraio MA. Pre-exercise carbohydrate ingestion: effect of the glycemic index on endurance exercise performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30: 844–849, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spieth LE, Harnish JD, Lenders CM, Raezer LB, Pereira MA, Hangen SJ, Ludwig DS. A low-glycemic index diet in the treatment of pediatric obesity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 154: 947–951, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stevenson EJ, Williams C, Mash LE, Phillips B, Nute ML. Influence of high-carbohydrate mixed meals with different glycemic indexes on substrate utilization during subsequent exercise in women. Am J Clin Nutr 84: 354–360, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stevenson E, Williams C, McComb G, Oram C. Improved recovery from prolonged exercise following the consumption of low glycemic index carbohydrate meals. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 15: 333–349, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Topping DL, Clifton PM. Short-chain fatty acids and human colonic function: roles of resistant starch and nonstarch polysaccharides. Physiol Rev 81: 1031–1064, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valtuenâ S, Pellegrini N, Ardigò D, Del Rio D, Numeroso F, Scazzina F, Monti L, Zavaroni I, Brighenti F. Dietary glycemic index and liver steatosis. Am J Clin Nutr 84: 136–142, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wee SL, Williams C, Gray S, Horabin J. Influence of high and low glycemic index meals on endurance running capacity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 31: 393–399, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wee SL, Williams C, Tsintzas K, Boobis L. Ingestion of a high-glycemic index meal increases muscle glycogen storage at rest but augments its utilization during subsequent exercise. J Appl Physiol 99: 707–714, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu CL, Nicholas C, Williams C, Took A, Hardy L. The influence of high-carbohydrate meals with different glycaemic indices on substrate utilisation during subsequent exercise. Br J Nutr 90: 1049–1056, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu CL, Williams C. A low glycemic index meal before exercise improves endurance running capacity in men. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 16: 510–527, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia Z, Sniderman AD, Cianflo K. Acylation-stimulating protein (ASP) deficiency induces obesity resistance and increased energy expenditure in ob/ob mice. J Biol Chem 277: 45874–45879, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zurlo F, Lillioja S, Esposito-Del Puente A, Nyomba BL, Raz I, Saad MF, Swinburn BA, Knowler WC, Bogardus C, Ravussin E. Low ratio of fat to carbohydrate oxidation as predictor of weight gain: study of 24-h RQ. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 259: E650–E657, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]