Abstract

Although lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DlCO) is a widely used test of diffusive O2 transfer, few studies have directly related DlCO to O2-diffusing capacity (DlO2); none has used the components of DlCO, i.e., conductance of alveolar membrane and capillary blood, to predict DlO2 from rest to exercise. To understand the relationship between DlCO and DlO2 at matched levels of cardiac output, we analyzed cumulative data from rest to heavy exercise in 43 adult dogs, with normal lungs or reduced lung capacity following lung resection, that were studied by two techniques. 1) A rebreathing (RB) technique was used to measure DlCO and pulmonary blood flow at two O2 tensions, independent of O2 exchange. DlCO was partitioned into CO-diffusing capacity of alveolar membrane and pulmonary capillary blood volume using the Roughton-Forster equation and converted into an equivalent DlO2, [DlO2(RB)]. 2) A multiple inert-gas elimination technique (MIGET) was used to measure ventilation-perfusion distributions, O2 and CO2 exchange under hypoxia, to derive DlO2 [DlO2(MIGET)] by the Lilienthal-Riley technique and Bohr integration. For direct comparisons, DlO2(RB) was interpolated to the cardiac output measured by the Fick principle corresponding to DlO2(MIGET). The DlO2-to-DlCO ratio averaged 1.61. Correlation between DlO2(RB) and DlO2(MIGET) was similar in normal and post-resection groups. Overall, DlO2(MIGET) = 0.975 DlO2(RB); mean difference between the two techniques was under 5% for both animal groups. We conclude that, despite various uncertainties inherent in these two disparate methods, the Roughton-Forster equation adequately predicts diffusive O2 transfer from rest to heavy exercise in canines with normal, as well as reduced, lung capacities.

Keywords: oxygen-diffusing capacity, multiple inert-gas elimination technique, rebreathing technique, Roughton-Forster relationship, lung resection, dog

the impetus for measuring lung diffusing capacity arose because two famous investigators (Christian Bohr and John Scott Haldane) reported in the 1890's using independent methods (2, 8) that O2 was actively secreted into pulmonary capillary blood, so that O2 tension of blood leaving the lung was higher than that in alveolar air. August and Marie Krogh (26, 27) were skeptical of the secretion theory, owing to uncertainties in the techniques. Krogh and Bohr recognized a need to measure diffusing capacity using a gas other than O2 to determine whether passive diffusion could support the levels of O2 uptake during exercise. Haldane was the first to measure carbon monoxide (CO) uptake at rest on himself (7). Based on Haldane's measurements, Bohr (1) published the first values of CO-diffusing capacity (DlCO) and translated Haldane's DlCO into O2-diffusing capacity (DlO2), taking into account the relative molecular weight (MW) and solubility (α, in ml·ml−1·atm−1 at 37.5°C) of the two gases. The generally used conversion factor is DlO2/DlCO =  /

/ ·αO2/αCO =

·αO2/αCO =  /

/ ·0.0239/0.0182 = 1.23 (range 1.1–1.4), where MWCO and MWO2 are the molecular weight of CO and O2, and αO2 and αCO are the solubility of O2 and CO, respectively (24, 30, 42). Bohr also derived the famous Bohr integral to interpret the data but erroneously concluded that O2 secretion was required to raise O2 uptake above 1.5 l/min. Marie Krogh, using a breath-holding method, measured DlCO at rest and exercise (27) and showed that DlO2 rose to two to four times that measured at rest by Bohr, sufficient to support O2 uptake during exercise, even at high altitude, without invoking O2 secretion. Thus diffusion was established as the process of O2 transfer within pulmonary alveoli.

·0.0239/0.0182 = 1.23 (range 1.1–1.4), where MWCO and MWO2 are the molecular weight of CO and O2, and αO2 and αCO are the solubility of O2 and CO, respectively (24, 30, 42). Bohr also derived the famous Bohr integral to interpret the data but erroneously concluded that O2 secretion was required to raise O2 uptake above 1.5 l/min. Marie Krogh, using a breath-holding method, measured DlCO at rest and exercise (27) and showed that DlO2 rose to two to four times that measured at rest by Bohr, sufficient to support O2 uptake during exercise, even at high altitude, without invoking O2 secretion. Thus diffusion was established as the process of O2 transfer within pulmonary alveoli.

Marie Krogh (27) in 1915 first proposed the use of DlCO to infer physiological limits of diffusive O2 transfer, assuming DlO2 ≈ 1.23·DlCO, which took into account the relative tissue diffusivities for O2 and CO, but not the relative conductance of capillary blood (ΘO2 and ΘCO, respectively, in ml gas·min−1·ml blood−1·mmHg−1). In the 1950's, Roughton and Forster (34) partitioned DlCO into separate resistances imposed by the alveolar membrane (DmCO) and capillary blood (ΘCO·Vc), i.e.,

|

(1) |

where ΘCO (ml CO·min−1·ml blood−1·mmHg−1) is the empirical CO uptake by whole blood measured in vitro, and Vc is pulmonary capillary blood volume (ml). Half a century later, the true values of ΘO2 and ΘCO remain controversial, and no study has formally established whether DmCO and Vc accurately predict diffusive O2 transfer. Resistance of the blood for CO uptake is thought to be greater than that for O2 uptake. There have been concerns that true DmCO and Vc are sensitive to inspired O2 tension (18), thereby introducing errors when inferring O2 transfer from CO uptake measured at different alveolar O2 tensions. As stated by Hughes and Bates in a recent review (24): “…there is still uncertainty over the relative importance of the alveolar capillary membrane versus the red cells as rate-limiting steps in the overall transfer of carbon monoxide from gas to blood.”

In view of the above uncertainties, we tested the assumption that DmCO and Vc in the Roughton-Forster equation accurately predict DlO2 from rest to heavy exercise. In separate cohorts of dogs with normal or reduced lung capacities, we compared the relationships between DlO2 and cardiac output derived using two independent methods. 1) A rebreathing (RB) technique was used to simultaneously measure DlCO and pulmonary blood flow from the uptake of inhaled tracer gases, CO and acetylene, respectively, independent of O2 and CO2 exchange. Measurements were made at two different O2 tensions to obtain DmCO and Vc (Eq. 1), which were converted into an equivalent DlO2 [DlO2(RB)] using the tissue diffusivity factor (1.23) and published values of ΘO2 and ΘCO for dog blood. 2) A multiple inert-gas elimination technique (MIGET) was used to estimate DlO2 [DlO2(MIGET)] from invasive measurement of ventilation-perfusion (V̇a/Q̇) distributions, and O2 and CO2 exchange during hypoxic exercise, utilizing the Lilienthal-Riley technique and Bohr integration. Whole lung DlO2(MIGET) represents the value that would be necessary to explain the part of the measured alveolar-arterial O2 tension gradient (A-aDo2) unexplained by V̇a/Q̇ mismatch (10). For a direct comparison of the two DlO2 estimates, DlO2(RB) was interpolated to the same cardiac output as that measured using the Fick principle, in conjunction with DlO2(MIGET) in the same animal. We reasoned that correspondence between two independent estimates of DlO2 at the same cardiac output supports the use of DmCO and Vc to predict the limits of diffusive O2 transfer during exercise.

METHODS

Animals.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all protocols and procedures. A total of 43 adult male foxhounds (2.5–5 yr of age) were studied in separate projects. Data from some of these animals have been published (6, 14, 15, 20–22, 29, 43). Twenty-six animals (body weight 26.4 ± 3.8 kg) had intact lungs. Another 17 animals (26.2 ± 5.1 kg) were studied 4–24 mo post-lung resection. Of the latter, 11 underwent right pneumonectomy (removal of 58% of lung units). Of these, nine animals had a custom-made silicone space-filling prosthesis implanted into the empty hemithorax at the time of pneumonectomy. The prosthesis was kept inflated via a subcutaneous injection port in four animals and remained uninflated in five animals; the remaining two animals had undergone right pneumonectomy without implantation of prosthesis. Six other animals underwent bilateral surgical resection of 70% of the lung units in two stages. In all animals, bilateral carotid arteries were exteriorized into dermal loops to permit acute catheterization without risking the complications of indwelling vascular catheters. Exercise measurements were obtained at least 4 mo after recovery from surgical procedures when adaptation to lung resection has stabilized. The RB and MIGET studies could not be performed together and were separated by an average of 4 mo. In most animals, RB measurements were performed before and after studies by MIGET.

Exercise training and apparatus.

Detailed description of these methods has been published elsewhere (19, 38). Briefly, animals were trained to run on a motorized treadmill wearing a sealed respiratory mask for measuring ventilation and gas exchange. Regular physical training continued throughout the studies. A built-in plastic cylindrical breathing orifice connects to an automatic pneumatic balloon three-way valve attached to a one-way, low-resistance valve and to a RB bag. Inspired and expired ventilation were measured using separate screen pneumotachographs. Expired gas concentrations are sampled continuously by a mass spectrometer distal to a mixing chamber. Minute ventilation, O2 uptake, CO2 output, and respiratory rate were followed breath by breath. Heart rate and rectal temperature were continuously recorded. All signals are digitized at 50 or 100 Hz and averaged every 10 breaths.

RB measurements.

The technique has been described extensively (6, 20, 29). Based on individual performance, measurements were obtained at three to five workloads of differing intensities. After warm-up at 6 mph and 0% grade for 3–5 min, the treadmill workload was increased to a preselected level. The RB bag was automatically prefilled with a volume of gas equal to the animal's average tidal volume plus 200 ml (atpd). The RB gas mixture contained 0.6% acetylene, 0.3% C18O, 9% He, and 30% O2 in a balance of either N2 or O2. After 3 min of exercise at each workload, the pneumatic valve was automatically switched at end expiration to allow the animal to inspire one bolus of the test gas mixture and then rebreathe this mixture in and out of an anesthetic bag for 6–12 s, while gas concentrations at the mouth were monitored. Complete (>90%) mixing was accomplished within three breaths in all animals. For RB maneuvers using the mixture containing 90% O2, the animal inspired 100% O2 from a large reservoir for 1 min before the maneuver to increase alveolar O2 tension to that in the test gas mixture.

System volume was measured from helium dilution, pulmonary blood flow from the slope of the exponential acetylene disappearance, and DlCO from the slope of the exponential C18O disappearance (3, 4). From DlCO measured at two different O2 tensions, DmCO and Vc were calculated using Eq. 1 and the value of ΘCO for dog blood given by Holland (12), corrected by the Arrhenius equation to a rectal temperature of 39°C, i.e.,

|

(2) |

where PaO2 is alveolar Po2. The equivalent DmO2 and DlO2 were calculated from DmCO and Vc using the value of θO2 = 3.9 ml O2·min−1·mmHg−1·ml blood−1 given by Yamaguchi et al. (44), and the tissue diffusivity between O2 (DmO2) and CO based on relative MWs and solubility, i.e., DmO2 = 1.23 DmCO, giving:

|

(3) |

One can reasonably assume this θO2 value when alveolar oxyhemoglobin saturation falls to ∼85%, a level reached in dogs at heavy exercise while breathing room air (25).

MIGET.

This technique has also been described extensively (14, 15, 17, 21, 22). Briefly, both external jugular veins and one exteriorized carotid artery were cannulated on the day of study. A Swan-Ganz catheter was advanced via one jugular catheter into the pulmonary artery for blood sampling and pressure monitoring. Six inert gases (SF6, ethane, cyclopropane, enflurane, acetone, and ether) were dissolved in saline and infused via the contralateral jugular vein at a constant rate, adjusted to ensure an adequate signal-to-noise ratio. Animals inspired 14% O2 from a large reservoir. At rest, the infusion was started 20 min before sampling to ensure equilibrium of inert-gas exchange at the blood-gas interface. During exercise, the infusion began at the onset of exercise. After running 3 min at a given workload when O2 uptake and ventilation neared a plateau, duplicate arterial and mixed venous blood samples and timed quadruplicate mixed expired gas samples were collected in glass syringes for measuring inert-gas concentrations by gas chromatography. Blood-gas partition coefficients of the inert gases were measured for each animal and corrected for the difference between the animal's body temperature during exercise and the water bath temperature at which the samples were equilibrated. Cardiac output was calculated by the direct Fick method.

From the multicompartmental distribution of V̇a/Q̇ ratios, the log scale second moments of the ventilation (log SDV̇) and perfusion (log SDQ̇) distributions were calculated. From the inert-gas data, barometric pressure, cardiac output, ventilation, hemoglobin, body temperature, base excess, inspired and mixed venous Po2 and Pco2, arterial Pco2, and A-aDo2 attributable to the observed V̇a/Q̇ mismatch were calculated, assuming complete alveolar-capillary diffusion equilibrium (40). The actual A-aDo2 was measured from arterial Po2 (PaO2) and the ideal PaO2. The difference between A-aDo2 predicted from V̇a/Q̇ mismatch and the measured A-aDo2 were assumed to reflect contribution from a combination of alveolar-end capillary diffusion limitation and postpulmonary shunting. Assuming negligible diffusion-perfusion (Dl/Q̇) inhomogeneity, a trial value of total lung DlO2 was selected and divided among the V̇a/Q̇ compartments, according to their blood flow. Bohr integration was performed on each V̇a/Q̇ compartment to account for nonlinearity of the O2 dissociation curve (10). The compartmental DlO2 are iterated until the predicted mixed PaO2 for the whole lung matches the measured value, at which point the whole lung DlO2 estimate represents that which accounts for the difference between measured and predicted A-aDo2 during hypoxic exercise. This estimate of DlO2 represents the minimal value that can account for the portion of A-aDo2 not explained by V̇a/Q̇ mismatch. Compared with breathing room air, breathing 14% O2 accentuates A-aDo2 caused by diffusion impairment and extrapulmonary shunt, while minimizing the A-aDo2 caused by V̇a/Q̇ mismatch and intrapulmonary shunt (28); differences arise because both O2 and inert gases are perturbed by V̇a/Q̇ mismatch and intrapulmonary shunt, but only O2 is diffusion limited and sensitive to extrapulmonary shunt.

Comparison of DlO2 estimated by two methods.

To directly compare DlO2 estimated by the RB method to that estimated by MIGET, it was necessary to match the cardiac output. For each animal, DlCO [DlCO(RB)] and DlO2(RB) were plotted against their respective simultaneously measured cardiac output, and the slope and intercept of individual regression lines were used to interpolate DlCO and DlO2 to the same cardiac output reached during hypoxic exercise using MIGET.

RESULTS

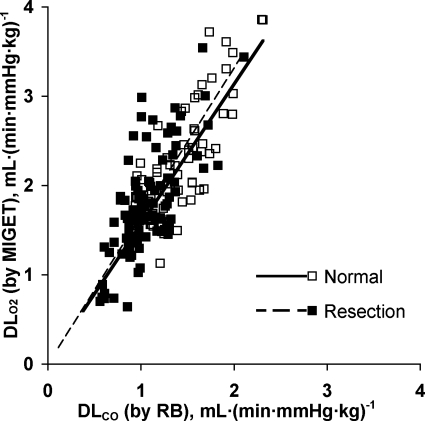

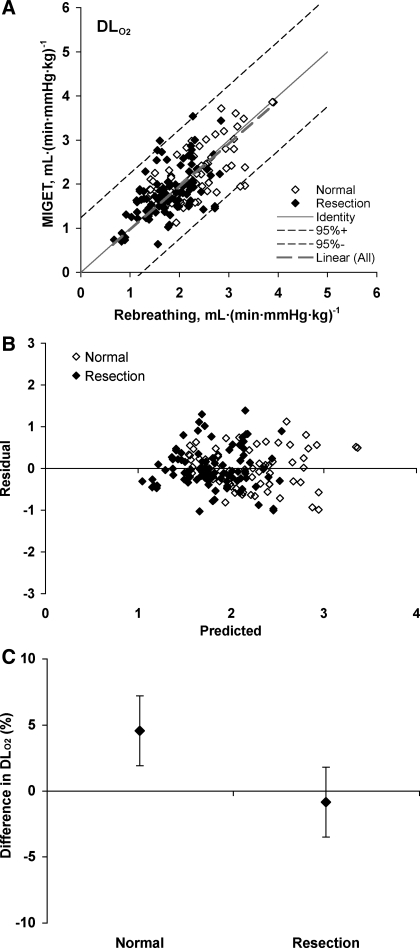

Measurements obtained at rest and during heavy exrecise in hypoxia are summarized in Table 1. The relationships between cardiac output, measured from acetylene disappearance during RB, and O2 uptake were similar to that measured by the direct Fick principle in conjunction with MIGET (Fig. 1), indicating no systematic difference in estimation by the two methods. No significant shunt flow developed in these animals. Using the RB technique, there is a linear relationship between DlCO and pulmonary blood flow in animals with intact lungs and in those post-resection (pooled data shown in Fig. 2). Using MIGET and Fick principle, there is a similar linear relationship between DlO2 and cardiac output in both groups (pooled data shown in Fig. 3). The slope of the correlation between DlO2(MIGET) and DlO2(RB) was not significantly different between normal animals with intact lungs [DlO2(MIGET) = 1.568 DlCO(RB), R2 = 0.63] and postresection animals [DlO2(MIGET) = 1.656 DlCO(RB), R2 = 0.49, Fig. 4]. The overall regression line through all data points was DlO2(MIGET) = 1.608 DlCO(RB), R2 = 0.59. Applying Eq. 3, the corresponding RB estimates of DmCO and Vc were converted to their equivalent DlO2 value [DlO2(RB)] and compared with DlO2(MIGET) measured at the same cardiac output. The correlations between DlO2(RB) and DlO2(MIGET) were similar for normal [DlO2(MIGET) = 0.944 DlO2(RB)] and post-resection [DlO2(MIGET) = 0.997 DlO2(RB)] groups. The overall correlation for all data points has a slope close to 1.0 [DlO2(MIGET) = 0.975 DlO2(RB)] (Fig. 5A). The residual vs. predicted values of the correlation are shown in Fig. 5B. The difference between estimates by the two methods averaged 4.5 ± 2.6% and −0.9 ± 2.6% (means ± SE) for normal and post-resection groups, respectively (Fig. 5C).

Table 1.

Multiple inert-gas elimination technique measurements breathing 14% O2

| Normal |

Resection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | 80% Peak Workload | Rest | 80% Peak Workload | |

| Ventilation, l·min−1·kg−1 | 0.588±0.242 | 4.084±1.587 | 0.794±0.427* | 3.493±0.784 |

| Tidal volume, ml/kg | 29.6±7.8 | 39.5±7.0 | 21.1±8.1* | 33.5±5.2 |

| Respiratory rate, beats/min | 22±15 | 104±26 | 48±42* | 107±28 |

| Oxygen uptake, ml·min−1·kg−1 | 9±3 | 61±32 | 10±3 | 47±11 |

| CO2 output, ml·min−1·kg−1 | 8±2 | 58±18 | 9±2* | 46±12 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 158±24 | 247±49 | 159±32 | 219±73 |

| Mean systemic arterial pressure, mmHg | 129±13 | 148±17 | 129±6 | 149±11 |

| Mean pulmonary arterial pressure, mmHg | 21±9 | 37±12 | 35±7* | 61±11 |

| Cardiac output, ml·min−1·kg−1 | 211±76 | 529±129 | 200±73 | 473±109 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 13.9±0.8 | 15.9±1.6 | 14.1±0.8 | 16.0±1.7 |

| Arterial pH | 7.39±0.02 | 7.24±1.02 | 7.38±0.02* | 7.34±0.07* |

| Arterial Pco2, mmHg | 36.0±2.1 | 33.6±3.7 | 37.6±3.0* | 39.7±6.2 |

| Arterial Po2, mmHg | 50.3±4.9 | 47.4±4.3 | 54.3±4.1* | 40.8±5.0 |

| Arterial O2 saturation, % | 80.4±4.3 | 70.5±10.1 | 82.4±3.7* | 59.2±10.7 |

| Arterial O2 content, ml/dl | 15.3±1.2 | 15.2±2.2 | 16.4±1.5* | 12.9±1.6 |

| O2 delivery, ml·min−1·kg−1 | 32±11 | 78±16 | 32±12 | 60±13 |

| Mixed venous pH | 7.37±0.02 | 7.31±0.08 | 7.36±0.02* | 7.27±0.08* |

| Mixed venous Pco2, mmHg | 40.1±3.4 | 47.6±7.6 | 42.7±3.4* | 54.6±10.8 |

| Mixed venous Po2, mmHg | 36.0±4.7 | 21.6±5.6 | 37.1±3.4 | 17.6±4.8 |

| Mixed venous O2 saturation, % | 58±6 | 22±11 | 57±6 | 15±9 |

| Mixed venous O2 content, ml/dl | 11±1 | 5±3 | 15±4 | 16±3 |

| O2 extraction, % | 28±7 | 70±13 | 30±5 | 71±11 |

| Log SDV̇ | 1.0±0.7 | 1.2±0.3 | 1.0±0.6 | 1.2±0.2* |

| Log SDQ̇ | 0.4±0.1 | 0.6±0.1 | 0.4±0.1 | 0.6±0.1* |

| A-aDo2 predicted, mmHg | 3.7±2.7 | 6.5±1.6 | 4.3±3.7 | 9.7±5.0 |

| A-aDo2 measured, mmHg | 4.0±5.1 | 12.2±3.8 | 2.3±4.6 | 17.1±6.3 |

| A-aDo2 (measured-predicted), mmHg | 0.4±4.0 | 5.7±3.5 | −2.0±6.6 | 7.4±9.0 |

| DlO2, ml·min−1·mmHg−1·kg−1 | 0.6±0.2 | 2.1±0.6 | 0.7±0.3 | 1.6±0.5 |

Values are means ± SD. Log SDV̇ and log SDQ̇, log scale second moments of ventilation and perfusion distributions, respectively; A-aDo2, alveolar-arterial O2 tension gradient; DlO2, O2 diffusing capacity.

P < 0.05 vs. corresponding value in normal group by ANOVA.

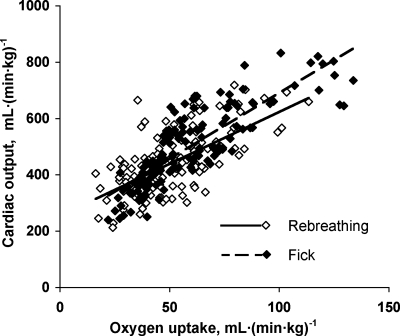

Fig. 1.

The relationships of cardiac output (Q̇c) to O2 uptake (V̇o2) from rest to exercise measured by rebreathing (RB) and direct Fick methods were not significantly different. Regression line through pooled data: Q̇c(RB) = 3.6 V̇o2 + 260, R2 = 0.41; Q̇c(Fick) = 4.7 V̇o2 + 225, R2 = 0.70.

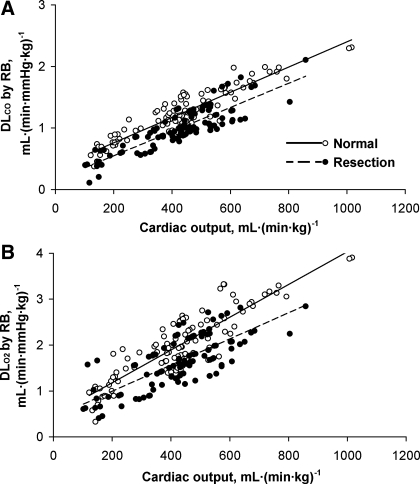

Fig. 2.

Relationships between carbon monoxide-diffusing capacity (DlCO) expressed under standard conditions (A), and the corresponding O2-diffusing capacity (DlO2) derived from DlCO of alveolar membrane (DmCO) and pulmonary capillary blood volume (Vc) (B) with respect to Q̇c were measured by RB technique in normal and post-resection groups. Regression lines are through pooled data. A: normal, DlCO = 0.0020 Q̇c + 0.351, R2 = 0.84; resection DlCO = 0.0020 Q̇c + 0.153, R2 = 0.74. B: normal DlO2 = 0.0036 Q̇c + 0.470, R2 = 0.77; resection DlO2 = 0.0028 Q̇c + 0.431, R2 = 0.56.

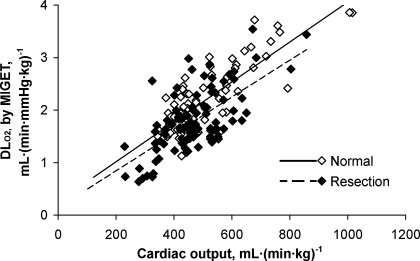

Fig. 3.

Relationship between DlO2 and Q̇c was measured by multiple inert-gas elimination technique (MIGET) in normal and post-resection animals. Pooled data: normal, DlO2 = 0.0038 Q̇c + 0.26, R2 = 0.66; resection, DlO2 = 0.0035 Q̇c + 0.14, R2 = 0.44.

Fig. 4.

Relationship between DlO2 measured by MIGET and DlCO measured by RB. Normal: DlO2 = 1.57 DlCO, R2 = 0.62; resection: DlO2 = 1.66 DlCO, R2 = 0.49; combined: DlO2 = 1.61 DlCO, R2 = 0.58.

Fig. 5.

A: relationship between DlO2 estimated from MIGET [DlO2(MIGET)] and from RB technique [DlO2(RB)] at corresponding levels of Q̇c. Slope of the correlation through all data, labeled Linear (All), is not significantly different from identity. Normal: DlO2(MIGET) = 0.94 DlO2(RB), R2 = 0.43; post-resection: DlO2(MIGET) = 1.00 DlO2(RB), R2 = 0.27; combined: DlO2(MIGET) = 0.97 DlO2(RB), R2 = 0.31. B: residuals and predicted values for the correlation between DlO2(MIGET) and DlO2(RB) for normal and post-resection groups. C: differences in DlO2 estimated by RB and MIGET were not different between normal and post-resection groups (4.5 ± 2.6 and −0.9 ± 2.6%, respectively; means ± SE).

DISCUSSION

Summary of findings.

In 43 normal and post-lung resection dogs, we measured the relationship between DlCO and pulmonary blood flow at incremental treadmill workloads using a RB technique at two O2 tensions to estimate DmCO and Vc. From these estimates, the equivalent DlO2 value was calculated based on the relative diffusivity of the two gases, as well as the empiric in vitro uptake of CO and O2 by whole blood. The same animals were studied using the MIGET at rest and exercise while breathing 14% O2 to estimate V̇a/Q̇ distributions. From measurements of blood gases and cardiac output, we predicted the A-aDo2 that would result from the observed degree of V̇a/Q̇ mismatch. If measured A-aDo2 exceeded that which was predicted, the difference was attributed to diffusion limitation and was used in conjunction with blood and expired gas parameters to derive an estimate of DlO2.

Both methods confirm a linear relationship between DlO2 and cardiac output, which reflects functional recruitment of the alveolar microvasculature. The DlO2-to-DlCO ratio averaged 1.61 for pooled data. There is reasonable correspondence between DlO2 estimated by these two methods with a mean difference of under 5% in animals with normal, as well as reduced, lung capacities. Results support the robustness of the Roughton-Forster model that uses serial CO conductance of the membrane and blood for assessing the limits of alveolar O2 uptake.

Critique of the methods.

The two methods of estimating DlO2 involve different theoretical principles, assumptions as well as experimental conditions, and invoke different potential sources of error. RB measurements were performed under ambient normoxia and hyperoxia. Measurements by MIGET were performed under ambient hypoxia. The two techniques were performed at least 4 mo following any surgical intervention, i.e., in a physiologically stable period. The two types of studies could not be performed together and were separated by an average of 4 mo. In most but not all animals, RB measurements were performed before and after studies by MIGET. Where available, the longitudinal RB data show no interval change in the relationship between DlCO(RB) and pulmonary blood flow. Although average body weight was similar between sham and post-resection animals, we normalized the data by body weight to minimize any discrepancy that might be caused by interval weight change. We expected the highly derived parameters (DlO2 calculated from DmCO and Vc) to exhibit greater variability than the primary measurements [DlO2(MIGET) and DlCO(RB)], and this was the case.

In the RB method, DmCO and Vc are solved by the Roughton-Forster equation (Eq. 1), using two simultaneous equations and DlCO measured at two alveolar O2 tensions. The Roughton-Forster equation implicitly assumes that DmCO and Vc are independent of inspired O2 tension. We have shown this assumption to be untrue. In finite-element model simulation of alveolar-capillary CO flux by diffusion, DmCO was found to decrease with increasing alveolar O2 tension (18), implying an overestimation of DmCO and, consequently, an obligatory underestimation of Vc by the RB method. The magnitude of the errors is modest (under 5%) compared with true alveolar CO flux in model simulation within a physiological range of capillary hematocrit (18). Although our group and others have used nitric oxide diffusing capacity (DlNO) as presumably a more direct measure of DmCO in human subjects at rest and exercise and in anesthetized dogs (16, 32), the interpretation and limits of DlNO remain to be understood. We have not been able to measure DlNO in exercising dogs due to their high respiratory rate, which renders the response time of the NO analyzer inadequate.

Using MIGET, DlO2 is estimated as the value that explains the portion of measured A-aDo2 that cannot be attributed to V̇a/Q̇ mismatch, assuming complete Dl/Q̇.homogeneity. Therefore, DlO2(MIGET) represents a minimal value that explains the blood and inert-gas data. If significant Dl/Q̇ mismatch developed in these animals upon exercise or after lung resection, the estimated DlO2(MIGET) would be correspondingly higher, i.e., MIGET could potentially overestimate true DlO2 in the presence of Dl/Q̇ heterogeneity. The magnitude of Dl/Q̇ heterogeneity and hence overestimation of DlO2 by MIGET is unknown.

Red cell uptake of CO and O2.

Variability in the assumed values of ΘCO and ΘO2, which were empirically measured in vitro, could alter the absolute values of DmCO and Vc, thereby altering the magnitude of derived DlO2(RB), but not its correlation with respect to DlO2(MIGET). A range of ΘCO values has been reported (5, 12, 33, 34, 39), including two values for dog blood given by Holland, representing different values of red cell membrane diffusivity (12). We reported our results using one of these values expressed at a realistic body temperature during exercise (Eq. 2). Repeating the analysis using the second ΘCO value for dog blood given by Holland (12) yields negligible difference in the resulting regression comparison between the DlO2 derived from DlCO and that measured as part of MIGET (data not shown). Reeves and Park (33) had shown, in a whole blood thin film preparation with minimal unstirred layer, that red cell CO uptake is entirely reaction rate limited at Po2 >100 Torr, and that capillary red cell CO diffusion equilibrium is rapidly achieved during uptake. In our normal and post-resection animals, the mean PaO2 at peak exercise workload while rebreathing a 30% O2 mixture averaged 117 ± 14 and 96 ± 15 Torr, respectively (means ± SD). Despite the lower mean PaO2 in the resection group, there was no difference in the relationship between DlO2 estimated by the two methods between normal and post-resection animals, suggesting that any variability in ΘCO due to intra-erythrocytic diffusion limitation had minor effects on the DlO2 comparison. A range of ΘO2 values also exists (31, 37, 44); we used the most recent value obtained by Yamaguchi et al. (44) in human blood using a stopped-flow technique after minimizing the effect of an unstirred layer around erythrocytes. It is uncertain whether a significant unstirred layer around capillary erythrocytes exists in vivo.

Previous comparisons of DlCO to DlO2.

The DlO2-to-DlCO ratios we observed (1.57–1.66) are consistent with that from earlier comparisons (1.36–1.71) and summarized by Hughes and Bates (24). The range of DlO2-to-DlCO ratios partly results from the fact that the ratio varies with the PaO2 at which DlCO is measured. The in vivo magnitude and distribution of Vc may also differ in normoxia (RB) and hypoxia (MIGET). Hempleman and Hughes (11) attempted to estimate DlO2 from DlCO using noninvasive data obtained from patients with interstitial fibrosis who show a diffusion limitation on exercise. Turino et al. (41) measured DlCO by a steady-state method compared with simultaneously measured DlO2 using the Lilienthal-Riley method under hypoxic conditions in normal subjects at rest and during supine and upright exercise. They showed an overall DlO2-to-DlCO ratio of 1.45, which is not very different from our results. Meyer et al. (30) used a RB method and 18O isotope to directly measure Dl18O2 and DlC18O in normal subjects at rest and during exercise. In another study from the same laboratory, DlC18O measured by RB technique was compared with DlO2 estimated by the Lilienthal-Riley technique in tracheostomized dogs during low-intensity hypoxic exercise (36). In both studies, the average DlO2/DlCO was 1.2, close to the theoretical ratio based on Krogh's tissue diffusion constants (KO2/KCO = 1.23). In contrast, Savoy et al. (35) used a steady-state technique in anesthetized, paralyzed dogs ventilated with a hypoxic gas mixture and reported a paradoxical DlO2/DlCO of 0.40–0.62; the lower ratio was likely due to the high sensitivity of the steady-state method to V̇a/Q̇ heterogeneity, that develops in anesthetized preparations. Such heterogeneity is minimized in our data obtained during exercise using the RB technique. None of the earlier studies compared DlCO to DlO2 at the same cardiac output, which is a major determinant of alveolar microvascular recruitment and contributes significantly to the variability in the measured values within and between techniques.

Using a similar approach as that described here, we previously reported an indirect comparison of DlO2 estimated using the Roughton-Forster equation and using MIGET in separate studies involving normal human subjects. DmCO and Vc were obtained by a RB technique in healthy nonsmokers at rest and during exercise using published ΘCO value for human blood (23), and compared DlO2 estimated by MIGET during hypoxic exercise in healthy subjects studied by Hammond and Hempleman (9) and in athletes studied by Hopkins et al. (13). The RB results were converted to equivalent DlO2 values using Eq. 3, expressed with respect to the simultaneously measured pulmonary blood flow, and compared with the relationships of DlO2 to cardiac output derived from V̇a/Q̇ distributions measured by MIGET. This indirect comparison (25) also demonstrates consistent agreement between DlO2 estimated by the two techniques.

We conclude that, despite the unavoidable variability involved in this analysis and the respective inherent sources of experimental error, the significant correlation, as well as the correspondence of DlO2 estimates obtained by two independent techniques support the use of DlCO, DmCO, and Vc in the Roughton-Forster model to derive an estimate of DlO2, to directly interpret alveolar O2 transfer from rest to heavy exercise in subjects with normal, as well as reduced, lung capacities.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01 HL045716, HL040070, HL054060, and HL062873.

DISCLOSURES

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Animal Resources Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center for veterinary care and assistance.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bohr C [Specific activity of lungs in respiratory gas uptake and its relation to gas diffusion through the alveolar wall] (German). Skand Arch Physiol 22: 221–280, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohr C Über die Lungenathmung. Skand Arch Physiol 2: 236–268, 1891. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlin JI, Cassidy SS, Rajagopal U, Clifford PS, Johnson RL Jr. Noninvasive diffusing capacity and cardiac output in exercising dogs. J Appl Physiol 65: 669–674, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlin JI, Hsia CCW, Cassidy SS, Ramanathan M, Clifford PS, Johnson RL Jr. Recruitment of lung diffusing capacity with exercise before and after pneumonectomy in dogs. J Appl Physiol 70: 135–142, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crapo RO, Bitterman N, Berlin SL, Forster RE. Rate of CO uptake by canine erythrocytes as a function of Po2. J Appl Physiol 67: 2265–2268, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dane DM, Hsia CC, Wu EY, Hogg RT, Hogg DC, Estrera AS, Johnson RL Jr. Splenectomy impairs diffusive oxygen transport in the lung of dogs. J Appl Physiol 101: 289–297, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haldane J The action of carbonic oxide on man. J Physiol 18: 430–462, 1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haldane J, Lorrain Smith J. The oxygen tension of arterial blood. J Physiol 120: 497–520, 1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond MD, Hempleman SC. Oxygen diffusing capacity estimates derived from measured VA/Q distributions in man. Respir Physiol 69: 129–147, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hempleman SC, Gray AT. Estimating steady-state DLO2 with nonlinear dissociation curves and VA/Q inequality. Respir Physiol 73: 279–288, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hempleman SC, Hughes JM. Estimating exercise DLO2 and diffusion limitation in patients with interstitial fibrosis. Respir Physiol 83: 167–178, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holland RAB Rate at which CO replaces O2 from O2Hb in red cells of different species. Respir Physiol 7: 43–63, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopkins SR, Belzberg AS, Wiggs BR, McKenzie DC. Pulmonary transit time and diffusion limitation during heavy exercise in athletes. Respir Physiol 103: 67–73, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsia CC, Johnson RL Jr, McDonough P, Dane DM, Hurst MD, Fehmel JL, Wagner HE, Wagner PD. Residence at 3,800 m altitude for 5 months in growing dogs enhances lung diffusing capacity for oxygen that persists at least 2.5 years. J Appl Physiol 102: 1448–1455, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsia CC, Johnson RL Jr, Dane DM, Wu EY, Estrera AS, Wagner HE, Wagner PD. The canine spleen in oxygen transport: gas exchange and hemodynamic responses to splenectomy. J Appl Physiol 103: 1496–1505, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsia CC, Yan X, Dane DM, Johnson RL Jr. Density-dependent reduction of nitric oxide diffusing capacity after pneumonectomy. J Appl Physiol 94: 1926–1932, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsia CCW, Carlin JI, Wagner PD, Cassidy SS, Johnson RL Jr. Gas exchange abnormalities after pneumonectomy in conditioned foxhounds. J Appl Physiol 68: 94–104, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsia CCW, Chuong CJC, Johnson RL Jr. Critique of the conceptual basis of diffusing capacity estimates: a finite element analysis. J Appl Physiol 79: 1039–1047, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsia CCW, Herazo LF, Johnson RL Jr. Cardiopulmonary adaptations to pneumonectomy in dogs. I. Maximal exercise performance. J Appl Physiol 73: 362–367, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsia CCW, Herazo LF, Ramanathan M, Johnson RL Jr. Cardiopulmonary adaptations to pneumonectomy in dogs. IV. Membrane diffusing capacity and capillary blood volume. J Appl Physiol 77: 998–1005, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsia CCW, Herazo LF, Ramanathan M, Johnson RL Jr, Wagner PD. Cardiopulmonary adaptations to pneumonectomy in dogs. II. Ventilation-perfusion relationships and microvascular recruitment. J Appl Physiol 74: 1299–1309, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsia CCW, Johnson RL Jr, Wu EY, Estrera AS, Wagner H, Wagner PD. Reducing lung strain after pneumonectomy impairs diffusing capacity but not ventilation-perfusion matching. J Appl Physiol 95: 1370–1378, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsia CCW, McBrayer DG, Ramanathan M. Reference values of pulmonary diffusing capacity during exercise by a rebreathing technique. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 152: 658–665, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes JM, Bates DV. Historical review: the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) and its membrane (DM) and red cell (Theta.Vc) components. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 138: 115–142, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson RL, Heigenhauser GJF, Hsia CCW, Jones NL, Wagner PD. Determinants of gas exchange and acid-base balance during exercise. In: Handbook of Physiology. Exercise: Regulation and Integration of Multiple Systems. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 1996, sect. 12, chapt. 12, p. 515–584.

- 26.Krogh A On the mechanism of gas exchange in the lungs. Skand Arch Physiol 23: 248–278, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krogh M The diffusion of gases through the lungs of man. J Physiol Lond 49: 271–296, 1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lilienthal JL, Riley RL, Proemmel DD, Franke RE. An experimental analysis in man of the pressure gradient from alveolar air to arterial blood during rest and exercise at sea level and at high altitude. Am J Physiol 147: 199–216, 1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonough P, Dane DM, Hsia CC, Yilmaz C, Johnson RL Jr. Long-term enhancement of pulmonary gas exchange after high-altitude residence during maturation. J Appl Physiol 100: 474–481, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer M, Scheid P, Riepl G, Wagner HJ, Piiper J. Pulmonary diffusion capacities for O2 and CO measured by a rebreathing technique. J Appl Physiol 51: 1643–1650, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mochizuki M A theoretical study on the velocity factor of oxygenation of the red cell. Jpn J Physiol 16: 658–666, 1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phansalkar AR, Hanson CM, Shakir AR, Johnson RL Jr, Hsia CC. Nitric oxide diffusing capacity and alveolar microvascular recruitment in sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 169: 1034–1040, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reeves RB, Park HK. CO uptake kinetics of red cells and CO diffusing capacity. Respir Physiol 88: 1–21, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roughton FJW, Forster RE. Relative importance of diffusion and chemical reaction rates in determining the rate of exchange of gases in the human lung, with special reference to true diffusing capacity of the pulmonary membrane and volume of blood in lung capillaries. J Appl Physiol 11: 290–302, 1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savoy J, Michoud MC, Robert M, Geiser J, Haab P, Piiper J. Comparison of steady state pulmonary diffusing capacity estimates for O2 and CO in dogs. Respir Physiol 42: 43–59, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scotto P, Ichinose Y, Patané L, Meyer M, Piiper J. Alveolar-capillary diffusion of oxygen in dogs exercising in hypoxia. Respir Physiol 68: 1–10, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staub NC, Bishop JM, Forster RE. Importance of diffusion and chemical reaction rates in O2 uptake in the lung. J Appl Physiol 17: 21–27, 1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeda S, Hsia CCW, Wagner E, Ramanathan M, Estrera AS, Weibel ER. Compensatory alveolar growth normalizes gas exchange function in immature dogs after pneumonectomy. J Appl Physiol 86: 1301–1310, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.te Nijenhuis FC, Jansen JR, Versprille A. Components of carbon monoxide transfer at different alveolar volumes during mechanical ventilation in pigs. Clin Physiol 17: 225–236, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torre-Bueno JR, Wagner PD, Saltzman HA, Gale GE, Moon RE. Diffusion limitation in normal humans during exercise at sea level and simulated altitude. J Appl Physiol 58: 989–995, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turino GM, Bergofsky EH, Goldring RM, Fishman AP. Effect of exercise on pulmonary diffusing capacity. J Appl Physiol 18: 447–456, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilhelm E, Battino R, Wilcock RJ. Low-pressure solubility of gases in liquid water. Chem Rev 77: 219–262, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu EY, Hsia CC, Estrera AS, Epstein RH, Ramanathan M, Johnson RL Jr. Preventing mediastinal shift after pneumonectomy does not abolish physiologic compensation. J Appl Physiol 89: 182–191, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamaguchi K, Nguyen PD, Scheid P, Piiper J. Kinetics of O2 uptake and release by human erythrocytes studied by a stopped-flow technique. J Appl Physiol 58: 1215–1224, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]