Abstract

Elastin is a major structural component of large elastic arteries and a principal determinant of arterial biomechanical properties. Elastin loss-of-function mutations in humans have been linked to the autosomal-dominant disease supravalvular aortic stenosis, which is characterized by stenotic lesions in both the systemic and pulmonary circulations. To better understand how elastin insufficiency influences the pulmonary circulation, we evaluated pulmonary cardiovascular physiology in a unique set of transgenic and knockout mice with graded vascular elastin dosage (range 45–120% of wild type). The central pulmonary arteries of elastin-insufficient mice had smaller internal diameters (P < 0.0001), thinner walls (P = 0.002), and increased opening angles (P = 0.002) compared with wild-type controls. Pulmonary circulatory pressures, measured by right ventricular catheterization, were significantly elevated in elastin-insufficient mice (P < 0.0001) and showed an inverse correlation with elastin level. Although elastin-insufficient animals exhibited mild to moderate right ventricular hypertrophy (P = 0.0001) and intrapulmonary vascular remodeling, the changes were less than expected, given the high right ventricular pressures, and were attenuated compared with those seen in hypoxia-induced models of pulmonary arterial hypertension. The absence of extensive pathological cardiac remodeling at the high pressures in these animals suggests a developmental adaptation designed to maintain right-sided cardiac output in a vascular system with altered elastin content.

Keywords: elastin, pulmonary hypertension, mechanics, remodeling

elastin is a structural extracellular matrix protein comprising >50% of the dry weight of large elastic arteries (37). Tropoelastin, together with microfibrils, forms insoluble elastic fibers that are laid down in repeating concentric rings, or lamellae, in the medial layer of arterial walls. Elastic fibers ensure uniform tension distribution throughout vessel walls and are primarily responsible for the elastic recoil properties of large elastic arteries (47). Elastic recoil imparts a hydraulic advantage to the circulatory system by converting intermittent cardiac output into steady flow, thereby reducing cardiac workload (38, 40). Stiffening of arteries has been shown to increase cardiac hemodynamic afterload, leading to impaired ventricular performance and subsequent heart failure (7, 42, 52).

The importance of elastin to normal vascular function was shown by linkage of elastin loss of function mutations to the disease supravalvular aortic stenosis (SVAS) [Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) no. 185500] (45). SVAS can occur sporadically or as a familial condition with autosomal dominant inheritance and is characterized by a congenital narrowing of the large elastic vessels, most typically the ascending aorta (31, 49). SVAS also occurs as part of Williams syndrome (OMIM no. 194050), where a microdeletion at 7q11.23 results in individuals hemizygous for the elastin gene (35). Systemic hypertension is frequently associated with SVAS, but is of variable penetrance and severity. In addition to localized narrowing of elastic arteries, nonstenotic regions are characterized by an increase in the number of elastic lamellae and smooth muscle cells (22). Elastin insufficiency also has implications for the pulmonary circulation, where pulmonary stenoses are frequently associated with SVAS and Williams syndrome (23, 36). Detailed descriptions of the vascular pathology and the existence and severity of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) are, however, limited in this group of patients. Although PAH is traditionally considered a disease of the peripheral lung vasculature, recent data suggest that the proximal elastic pulmonary arteries (PAs) contribute significantly to the increased right ventricular (RV) afterload in pulmonary hypertensive states (11, 48). This occurs through acute mechanisms like strain stiffening, as well as chronic adaptations like structural remodeling of vessel walls in response to elevated pulmonary pressures (48). Furthermore, measurement of these mechanical changes allows for improved mortality prediction in patients with PAH (27).

Mice heterozygous for elastin (Eln+/−) have many traits in common with individuals with SVAS. The mice have a high penetrance of systemic cardiovascular anomalies, including an increased number of aortic elastic lamellae and elevated systemic pressures (15, 47). In this study, we evaluate the anatomy, physiology, and biomechanical properties of the pulmonary circulation of C57BL6 mice with genetically determined graded elastin insufficiency. We show that elastin insufficiency results in mechanical and structural remodeling of the proximal PAs and elevated pulmonary circulatory pressures. Unlike existing models of pathological PAH, this model is one of congenital adaptation of the pulmonary cardiovascular system to insufficient elastin gene product dosage and is distinct from primary PAH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Study mice were 3-mo-old males and females in the C57BL/6 background to allow comparison of data with other studies and eliminate possible confounding variables caused by postnatal changes in the pulmonary circuit (9). Equal numbers of males and females were used in all experiments. Eln+/− mice bearing a heterozygous deletion of exon 1 of the mouse elastin gene (Eln+/−) have been described (24). Wild-type (WT) (Eln+/+) littermates from Eln+/− crosses were used as WT controls. Bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) transgenic mice were generated using human BAC (hBAC) clone CTB-51J22 containing the complete human elastin gene (hBAC-ELN) as described (19). hBAC-mWT mice are homozygous for both the human elastin transgene and endogenous mouse elastin gene (ELN+/+, Eln+/+). hBAC-mHET mice were generated from hBAC-mWT × Eln+/− crosses and are homozygous for the human elastin transgene and heterozygous for the mouse elastin gene (ELN+/+, Eln+/−). hBAC-mNULL mice were generated from hBAC-mHET × hBAC-mHET crosses and are homozygous for the human elastin transgene and null for the mouse elastin gene (ELN+/+, Eln−/−). All elastin-insufficient mice are fertile and have normal life spans. All animals were maintained under identical conditions in accordance with institutional guidelines, and all procedures were approved by the Animal Studies Committee of the Washington University School of Medicine. An observer blinded to genotype performed all analyses.

Hemodynamic measurements.

Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and placed on a warming pad. Isoflurane was maintained at 1% in air to minimize vasodilatory effects. A 1.4-F Millar microcatheter (model SPR671, Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was advanced through the internal jugular vein into the RV. Pressures were recorded for >15 min using Chart 5 software (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). If the heart rate fell <300 beats/min, it was assumed that the level of anesthesia or trauma was inhibiting cardiac function, and the measurements were excluded from analysis. Each genotype analyzed contained six animals. After death, the hearts, main PAs (MPA), and the extrapulmonary segments of the right (RPA) and left PAs (LPA) were excised, packed on ice, and tested within 12 h of excision. Pressure measurements in each genotype were verified by using a pressure transducer attached to a 26-gauge needle introduced percutaneously into the RV, as described (25), with confirmation of RV placement at postmortem (data not shown).

Elastin content measurement.

Four MPAs from each genotype were dissected free of extraneous connective tissue, minced, pooled, and hydrolyzed with 6 N HCl (41). Total protein and desmosine levels in hydrolysates were determined in triplicate using a Beckman 6300 amino acid analyzer, as described (3).

RV hypertrophy assessment.

Hearts were divided into RV and left ventricular plus septum compartments, blotted dry, and weighed. RV-to-body weight ratio was used to determine RV hypertrophy (RVH), since Eln+/− and hBAC-mNULL mice may manifest with mild left ventricular hypertrophy (47), potentially biasing the results. Each genotype analyzed contained six hearts.

Pressure-diameter testing.

RPAs and LPAs were mounted on a pressure arteriograph (Danish Myotechnology, Copenhagen, Denmark) in balanced physiological saline at 37°C. Vessels were transilluminated under a microscope connected to a charged-coupled device camera and computerized measurement system, as described (14), to allow continuous recording of vessel diameters. Intravascular pressure was increased from 0 to 90 mmHg in 10-mmHg steps (30 s/step) to minimize experiment time, while allowing operator supervision of diameter tracking. Each genotype analyzed contained six RPAs and six LPAs. Since RPA and LPA data were statistically the same, only RPA data are shown.

Opening angle measurement.

Opening angle measurements were performed as previously described (47). Rings were cut from RPAs and LPAs and then cut radially at the ventral surface. After equilibration, the opened ring was imaged, and the opening angle [subtended by lines connecting the midpoint of the inner circumference with the ends of the ring (6, 16)] was measured using Matlab software (The Mathworks, Natick, MA) (47). WT mouse opening angles were comparable to those measured in other rodent studies (17). Each genotype analyzed contained 12 vessel rings. Because RPA and LPA data were statistically the same, only RPA data are shown.

Vessel mechanics.

Incremental elastic modulus (Einc) was calculated as:

|

(1) |

where ΔPave is incremental change in average transmural pressure; ΔID is corresponding change in internal diameter; and ID, OD, and Pave are inner diameter, outer diameter, and average pressure at the beginning of the increment, respectively (5, 21). Calculated Einc for WT vessels was consistent with those from other studies (5, 8, 21). Each genotype analyzed contained nine vessels.

Data from test protocols were converted to stress and stretch ratios. Loaded inner diameter was calculated by assuming constant wall volume:

|

(2) |

where di, do, and l are loaded inner and outer diameters and length, respectively; and Di, Do, L, and T are unloaded inner and outer diameters, length, and thickness, respectively (14). In the stress notation, θ refers to circumferential axis. Mean circumferential stretch ratio (λθ) was calculated as (28):

|

(3) |

Assuming constant wall volume and a thin-walled tube, mean circumferential stress (σθ) was defined as:

|

(4) |

where Pi is pressure in vivo (30). To model transmural stress gradients, with and without residual stress, circumferential stretch ratio at the inner (di/Di) and outer wall (do/Do) of each PA was calculated using mean opening angle (to include residual stress) or an angle of zero (to exclude residual stress). All modeling was done with Matlab software (The Mathworks) (47). Since RPA and LPA data were statistically the same, only RPA data are shown.

Arterial histology.

RPAs and LPAs were inflated to 5-cmH2O pressure with gelatin to preserve patency and then formalin-fixed and embedded in paraffin (15). Five-micrometer-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Hart's elastic stain. For counting elastic lamellae and measuring wall thickness, vessels were divided into quadrants, with number and thickness determined in each quadrant using three sections per mouse. Wall thickness measurements included all three vessel layers (intima, media, and adventitia) and were measured from the lumen to the outermost limit of the adventitia. Only sections perpendicular to the vessel long axis were used for measurements. Each genotype analyzed contained six animals.

Vessel immunofluorescence.

Paraffin sections were blocked with 5% normal goat serum, and primary antibody was applied overnight at 4°C. Polyclonal anti-mouse recombinant tropoelastin (1:1,000) was used to detect mouse elastin, and polyclonal anti-human aortic elastin (1:500) was used to detect human elastin. Secondary fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch, Westgrove, PA) was applied at room temperature for 1 h. Images were captured with a Zeiss Axioskop microscope, an inline Zeiss Axiocam camera, and Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Peripheral artery analysis.

Lungs were inflated to 25-cmH2O pressure with 10% buffered formalin, fixed for 24 h, and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer-thick sections were stained with monoclonal α-smooth muscle actin antibody (1:400, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and Vector Mouse-on-Mouse Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), following manufacturer instructions. Sections were developed with Vector ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories) and diaminobenzidine and then counterstained with hematoxylin. Small vessels (15- to 50-μm external diameter) from three randomly chosen fields at ×10 magnification were identified and quantified as muscularized (actin staining >25% of vessel circumference) or nonmuscularized (<25%) (51) using Image J software (version 1.37, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij), and the percentage of muscularized arteries was calculated. Hart's stained sections were used to count alveoli and small vessels from three randomly chosen fields at ×10 magnification, and average ratios of arteries to alveoli were calculated. Each genotype analyzed contained six different animals.

Statistical analyses.

Analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA to determine differences between more than two groups of data, and Student's t-tests (2-tailed distribution with 2-sample equal variance) were used for paired value comparisons. Results are presented as mean values ± SE, unless otherwise stated. P values <0.05 were chosen as the threshold for statistically significant differences.

RESULTS

Study mice.

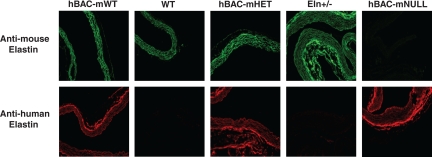

Mice from all five genotypes did not differ in age, weight, or sex distribution (Table 1). Desmosine content of WT MPA was defined as 100% elastin content (Table 1). By comparison, Eln+/− MPA contain ∼60% of WT elastin levels, hBAC-mHET MPA ∼85% of WT levels, and hBAC-mNULL MPA ∼45% of WT levels. hBAC-mWT MPA have an increased elastin content of ∼120% of WT levels. These values are in agreement with desmosine levels measured in both systemic vessels (19) and whole lung (41). Immunostaining with human and mouse elastin-specific antibodies (Fig. 1) demonstrates that PA from WT and Eln+/− mice contain only mouse elastin, and that human elastin incorporates into elastic fibers with mouse elastin in PA from hBAC-mWT and hBAC-mHET mice. hBAC-mNULL PA are humanized for elastin protein and contain human elastin exclusively.

Table 1.

Characterization of mice with altered elastin dosage

| hBAC-mWT | WT | hBAC-mHET | Eln+/− | hBAC-mNULL | P (ANOVA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, days | 100±4 | 99±6 | 101±3 | 98±5 | 99±3 | 0.85 |

| Body weight, g | 32±4 | 30±4 | 31±3 | 32±2 | 31±3 | 0.66 |

| Sex ratio (male:female) | 52:48 | 50:50 | 49:51 | 51:49 | 51:49 | 0.74 |

| Elastin content, pg desmosine/μg protein | 3.13 | 2.64 | 2.25 | 1.53 | 1.19 | 0.53 |

| Elastin content, %WT | 119 | 100 | 85 | 59 | 45 | |

| RV systolic pressure, mmHg | 19.8±2.8 | 19.8±2.8 | 32.1±4.1 | 54.6±5.1 | 77.9±9.6 | <0.00001 |

| RV diastolic pressure, mmHg | 2.5±1.1 | 3.1±2.1 | 9.9±4.1 | 13.2±3.6 | 26.3±3.6 | <0.0001 |

Values are means ± SE. WT, wild type; RV, right ventricle. See materials and methods for definition of mouse genotypes. Equal numbers of male and female mice were used in each experiment. Elastin content determined using 4 main pulmonary arteries per genotype. RV pressures are for 6 animals per genotype analyzed.

Fig. 1.

Serial pulmonary artery (PA) segments were immunostained for mouse (top) and human (bottom) elastin to demonstrate incorporation of human elastin in hBAC-mWT and hBAC-mHET PA, and humanization of hBAC-mNULL PA elastin. Not all sections are perpendicular to the vessel long axis. Magnification ×40. See materials and methods for definition of mouse genotypes.

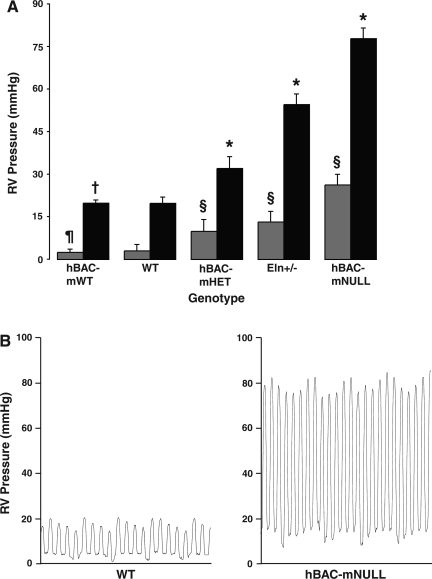

Elastin-insufficient mice have markedly elevated RV pressures.

Compared with WT animals, elastin-insufficient mice demonstrate a striking elevation in RV systolic and diastolic pressures in a manner inversely proportional to elastin content (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). By comparison, mice with supraphysiological elastin content (hBAC-mWT) show no difference in systolic (P = 0.96) or diastolic (P = 0.41) pressures. Representative catheter pressure tracings from WT and hBAC-mNULL mice are shown in Fig. 2B.

Fig. 2.

A: right ventricular (RV) pressure was measured using a microcatheter introduced through the internal jugular vein. n = 6 Animals per genotype. Bars represent mean systolic (solid) and diastolic (shaded) pressures ± SE. *P < 0.00001, §P < 0.0001, ¶P = 0.96, and †P = 0.41 vs. wild type (WT). B: pressure tracings from WT and hBAC-mNULL mice demonstrating measured systolic and diastolic pressure differences.

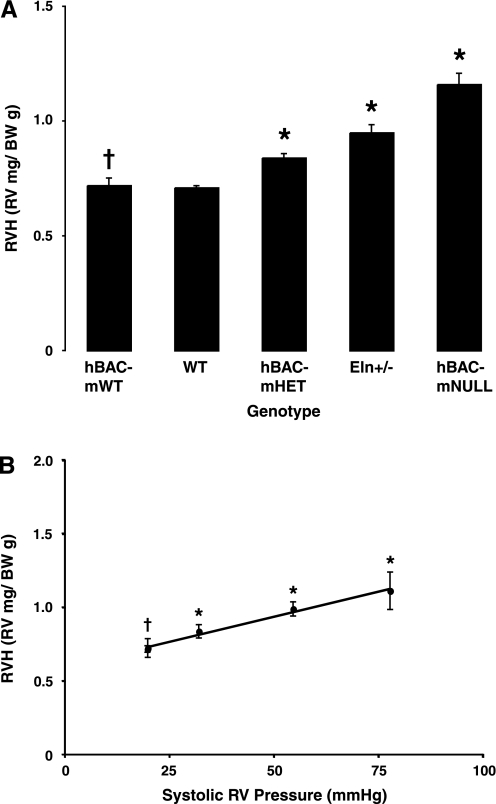

RVH correlates with RV systolic pressure.

Elastin-insufficient mice demonstrate RVH (Fig. 3A) as elastin content decreases and RV pressure increases. Figure 3B expresses RVH as a function of systolic pressure and demonstrates that RVH and RV systolic pressure are very closely correlated. hBAC-mWT mice again demonstrate no difference from WT controls (P = 0.79).

Fig. 3.

A: RV hypertrophy (RVH) was assessed by calculating RV-to-body weight (BW) ratios. n = 6 Hearts per genotype. Bars represent means ± SE. *P = 0.0001 and †P = 0.79 vs. WT. B: RVH correlates closely with RV systolic pressure. Circles represent mean elastin-insufficient RVH at each operating pressure ±SE. *P < 0.0001 and †P = 0.79 vs. WT. R2 = 0.88 for RVH vs. RV pressure.

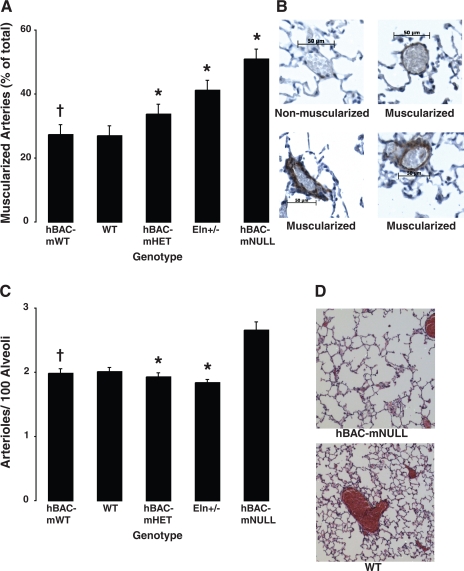

Elastin-insufficient mice exhibit intrapulmonary arteriolar remodeling.

Muscularization of peripheral arterioles, assessed by α-smooth muscle actin staining, is increased in elastin-insufficient mice in proportion to RV systolic pressure (Fig. 4, A and B). Although mouse models traditionally demonstrate only small amounts of peripheral vascular remodeling in response to PAH, the arteriolar muscularization in our mice is markedly attenuated compared even with historic controls (12, 13, 18, 51), despite the greater pressures in our animals.

Fig. 4.

A: morphometric analysis of muscularized PAs (15- to 50-μm external diameter) using α-smooth muscle actin staining. Vessels were quantified as muscularized (actin staining >25% of vessel circumference) or nonmuscularized (<25%) and expressed as a percentage. n = 36 Fields per genotype (6 fields from 6 animals per genotype). Bars represent means ± SE. *P = 0.0003 and †P = 0.77 vs. WT. B: lung sections were immunostained for smooth muscle cell actin before hematoxylin staining. Representative nonmuscularized and muscularized arterioles are shown. Scale bar = 50 μm. C: loss of distal PAs in elastin-insufficient mice. Arterioles (15- to 50-μm external diameter) and alveoli were counted, and the ratio of arterioles to 100 alveoli was calculated. n = 36 Fields per genotype (6 fields from 6 animals per genotype). Bars represent means ± SE of arteries per 100 alveoli. *P = 0.02 and †P = 0.78 vs. WT. hBAC-mNULL mice were excluded from the ANOVA analysis due to enlarged alveoli. D: lungs were inflated to 25-cmH2O pressure to demonstrate congenital air space enlargement in hBAC-mNULL lungs (top) compared with WT controls (bottom).

Peripheral vessel numbers per 100 alveoli also decline as RV pressures increase (WT = 2.01 ± 0.06, hBAC-mHET = 1.93 ± 0.05, Eln+/− = 1.84 ± 0.04, P = 0.02, Fig. 4C) and are again attenuated compared with historic controls (13, 34, 51). The only genotype where peripheral vessel number apparently increases is hBAC-mNULL mice (2.66 ± 0.12). This, however, is due to alveolar enlargement, resulting from failed secondary alveolar septation (Fig. 4D) (41) and a consequent decrease in alveolar number. hBAC-mWT mice (1.99 ± 0.07) are again no different from WT controls (P = 0.78).

Elastin insufficiency alters central PA architecture.

Despite comparable ages and body weights, RPA and LPA in hBAC-mNULL mice, and to lesser extent in Eln+/− mice, had smaller diameters in vivo compared with other genotypes (not shown). Ex vivo full wall thickness (intima, media, and adventitia) of both RPA and LPA decreases in proportion to the degree of elastin insufficiency, as does inner (luminal) diameter (Table 2, values for RPA shown). Interestingly, no discrete pulmonary stenoses were noted in any of the elastin-insufficient PA. Lamellar number increases with decreasing elastin content (Table 2), a finding consistent with systemic vessels in Eln+/− mice (15, 24, 47) and SVAS patients (24). As before, hBAC-mWT mice show no differences in PA wall thickness (P = 0.90), inner diameter (P = 0.98), or lamellar number (P = 0.91) compared with WT mice.

Table 2.

Morphological changes in elastin-insufficient right PA

| hBAC-mWT | WT | hBAC-mHET | Eln+/− | hBAC-mNULL | P (ANOVA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA wall thickness, μm | 68.9±2.7 | 69.0±2.8 | 65.7±2.9 | 61.7±2.4 | 55.4±2.6 | 0.002 |

| Unloaded inner PA (lumen) diameter, μm | 527±10 | 529±11 | 486±10 | 449±12 | 407±7 | <0.0001 |

| Wall thickness-to-lumen ratio | 84±3 | 84±4 | 87±5 | 88±4 | 88±4 | 0.90 |

| Operating diameter at systolic pressure, μm | 1,051±50 | 1,044±52 | 1,175±63 | 1,114±67 | 1,160±54 | 0.22 |

| Elastic lamellae | 4.1±0.2 | 4.1±0.2 | 4.9±0.1 | 5.7±0.3 | 6.4±0.4 | <0.0008 |

Values are means ± SE. *Both right and left pulmonary artery (PA) segments were evaluated. Differences between the two sides were not significant. Data are representative of both right and left PA measurements. Vessel thickness, diameter, and lamellar measurements are for 6 right PA per genotype analyzed.

Einc is similar over the in vivo pressure range between genotypes.

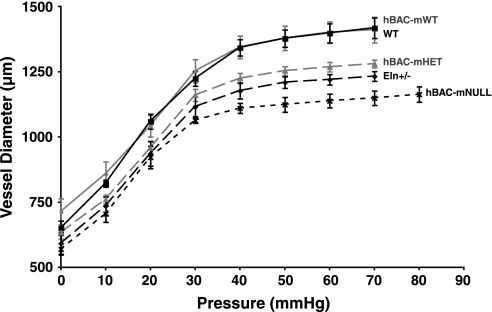

LPA and RPA pressure-diameter curves demonstrate a nonlinear increase in vessel diameter with progressive pressure loading (Fig. 5, RPA data shown). Calculation of the PA Einc over the in vivo pressure change confirmed that vessel stiffness is equivalent in all five genotypes over their respective pulse pressure increments, despite different elastin contents (Table 3, values for RPA shown). The most interesting finding was that PA operating diameter (lumen diameter at RV systolic pressure) in all five groups is similar (Table 3), indicating that in vivo cross-sectional area during systole is the same between genotypes, despite differences in their starting geometries and blood pressures.

Fig. 5.

Right PA pressure-diameter curves (diameter change per unit pressure increase) for all 5 genotypes. n = 6 Vessels per genotype. Points represent mean diameter at each pressure ±SE.

Table 3.

Biomechanical properties of elastin-insufficient right PA

| hBAC-mWT | WT | hBAC-mHET | Eln+/− | hBAC-mNULL | P (ANOVA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opening angle, ° | 122±10 | 120±11 | 131±8 | 143±8 | 158±9 | 0.0001 |

| Einc, kPa | 138±7.8 | 141±9.2 | 134±7.8 | 130±7.0 | 137±8.3 | 0.87 |

| λθ | 1.85±0.12 | 1.84±0.16 | 2.25±0.16 | 2.52±0.15 | 2.55±0.17 | 0.007 |

| σθ, kPa | 95±13 | 92±12 | 222±30 | 473±64 | 741±126 | <0.0001 |

Values are means ± SE. Einc, elastic modulus; λθ, mean circumferential stretch ratio; σθ, mean circumferential stress. Both right and left PA segments were evaluated. Differences between the two sides were minimal and not significant. Data are representative of both right and left PA measurements. Opening angle measurements are for 6 right PA per genotype analyzed.

Elastin-insufficient PA adapt to increased mechanical stresses.

Calculation of wall thickness-to-luminal cross-sectional area ratios demonstrates that changes in wall thickness and vessel diameter are proportional, with no difference in the ratios between genotypes (P = 0.90). This is not typical of hypertensive vessels and indicates that mechanical remodeling of the vessel walls has normalized vessel stress in each genotype in a manner different from typical models of PAH (10, 43) that involve postnatal injury.

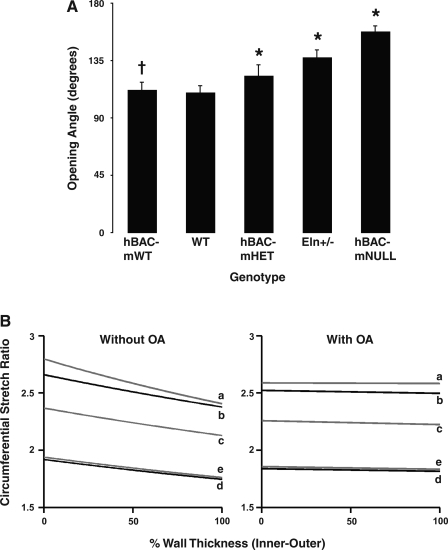

Residual stress in large elastic arteries is thought to be a homeostatic mechanism for normalizing the circumferential stress gradient through the artery wall, thereby ensuring a uniform transmural stress distribution in vivo (6). Without residual stress, circumferential stress would vary from a maximum at the inner wall surface to a minimum at the outer wall surface (20), producing a transmural stress gradient proportional to the blood pressure within the vessel lumen. Residual stress is incorporated into biomechanical modeling using opening angle at the zero-stress state to allow for calculation of the transmural stress gradient (6, 30, 46). As PA elastin content decreases, the measured mean opening angle increases (Table 3 and Fig. 6A), indicating increased residual stress in elastin-insufficient vessels. Again, hBAC-mWT animals are no different from WT animals (P = 0.77). Modeling of PA transmural stress distributions under physiological conditions with inclusion and exclusion of opening angles indicates that the increased residual stress in elastin-insufficient PA effectively normalizes the transmural stress gradients in each genotype (Fig. 6B), despite significant differences in measured systolic pressures.

Fig. 6.

A: arterial rings spring open when cut radially. The angle subtended by the resulting segment is the opening angle (OA), an indicator of circumferential residual strain. Bars represent mean OA (in degrees) ±SE; n = 12 rings per genotype. *P = 0.0001 and †P = 0.77 vs. WT. B: modeling of transmural stress distribution of vessels from each genotype under physiological conditions with inclusion and exclusion of OAs. a, hBAC-mNULL; b, Eln+/−; c, hBAC-mHET; d, WT; e, hBAC-mWT. Models are based on measurements from 6 vessels per genotype.

DISCUSSION

Elastin-insufficient mice demonstrate anatomic remodeling of the proximal vasculature that includes thinner vessel walls and preserved artery wall thickness-to-lumen ratios (Table 2). Our laboratory's previous work demonstrated that blood vessels from newborn calves with hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension manifest with a two- to fourfold increase in pulmonary vascular elastin production (33). Other studies have reported a predisposition to pathological PAH in rats with increased endogenous elastase activity (29) and protection from PAH in mice overexpressing elastase inhibitors (51). Collectively, these data suggest that elastin modulates changes in vessel wall stresses resulting from elevated pulmonary pressures, and that elastin insufficiency may lead to a biomechanical disadvantage predisposing mice to the development of elevated pulmonary pressures.

PAH induces a marked change in the opening angles of central pulmonary vessels (17), suggesting that changes in vascular circumferential residual stress may effectively normalize transmural stress distribution through elastin-insufficient vessel walls. Our data show that opening angle does increase with decreasing elastin content (Table 3), indicating that circumferential residual stress increases to compensate for the higher transmural stresses experienced at higher physiological operating pressures in elastin-insufficient mice. Mathematical modeling that includes circumferential residual stress results in a more uniform distribution of transmural stress (Fig. 6), noticeably decreasing the stress at the inner wall in all five genotypes compared with modeling where residual stress is excluded.

The unloaded internal PA diameter (and hence vessel cross-sectional area) decreases with decreasing elastin content (Table 2). The smaller unloaded dimensions of elastin-insufficient vessels result in downward displacement of the elastin-insufficient pressure-diameter curves and hence smaller dimensions at each measured pressure. Since decreased luminal area increases resistance to blood flow, our data suggest that the increased RV pressures associated with elastin insufficiency function to expand the proximal vascular cross-sectional area to accommodate cardiac output by overcoming the increased RV afterload imposed by the smaller starting dimensions of elastin-insufficient vessels. The result is similar operating diameters at measured systolic pressures in all five genotypes, allowing for maintenance of cardiac output and perfusion pressure. The larger circumferential stretch ratio of elastin-insufficient PA at measured operating pressures (Table 3) indicates a greater degree of stretch from the zero-stress state in elastin-insufficient animals, suggesting that this phenomenon is indeed occurring.

In contrast to elastin-insufficient PA, hBAC-mWT vessels display no architectural or biomechanical differences from WT PA. This suggests that evolution has optimized the elastin content of PA with respect to mechanical function, and that, while elastin insufficiency negatively affects tissue mechanics, elastin excess, at least to 120% of WT levels, has no structural or mechanical impact. Whether greater amounts of elastin (>120% of WT levels) will alter vessel mechanics is unknown.

Our findings differ from those seen in traditional models of adult-onset PAH (40, 52). Our mice experience elastin insufficiency throughout embryonic development, and the attenuated cardiovascular remodeling in elastin-insufficient mice may represent physiological adaptation of the pulmonary circulatory system to congenital elastin insufficiency rather than a pathological response to elevated pulmonary pressures. Three lines of evidence support this hypothesis.

First, chronic PAH in normal conditions leads to elevation of RV pressures and subsequent RVH. In our model, RV pressures increase in proportion to decreased vascular elastin content, with concomitant RVH. However, despite a strong correlation between RV systolic pressure and RVH, direct comparison to historic WT controls developing PAH following hypoxic exposure (44, 51) indicate that the degree of hypertrophy per unit pressure increase is markedly attenuated in elastin-insufficient animals. hBAC-mNULL mice demonstrate an increase in RV-to-body weight ratio of only ∼50%, while experiencing pulmonary pressures almost four times higher than that of WT mice (∼80 vs. ∼20 mmHg). In comparison, in adult WT mice exposed to chronic hypoxia (51), systolic pressure increases from 30 to 50 mmHg result in an increase in RV-to-body weight ratio of ∼80%. Although there were differences in the methods of anesthesia and RV pressure measurements between the two studies, they do not account for the observed attenuation in RV remodeling at each pressure seen in the elastin-insufficient mice.

Second, PAH is associated with medial hypertrophy of muscular arteries, abnormal muscularization of peripheral arterioles, and loss of peripheral arterial vessels in mice (4, 12, 51) and humans (10, 43). In our model, peripheral arterial muscularization and distal vessel loss occur in proportion to elastin insufficiency and RV pressure; however, direct comparison to historic hypoxic WT controls (51) again reveals that the degree of change is far less than expected, given the pulmonary pressure elevations. For the same pressure changes described for RVH above, our mice demonstrate an increase in peripheral arteriolar muscularization from ∼20% in WT mice to ∼55% in hBAC-mNULL mice. However, mice developing PAH following exposure to chronic hypoxia (51) demonstrate an increase in peripheral arteriolar muscularization from ∼20 to ∼70%, despite the smaller pressure difference.

Third, structural remodeling of arteries associated with hypertensive states results in altered vascular geometry (39). In pathological remodeling, inner diameter decreases and wall thickness increases in an attempt to reduce circumferential wall stress back to that experienced at normotensive pressures (2). In our model, circumferential wall stress increased with elastin insufficiency. Although inner vessel diameter is decreased, wall thickness also decreases, resulting in wall thickness-to-lumen ratios that are identical in all genotypes (Table 2). These three groups of findings indicate that vascular remodeling in our model is fundamentally different than that seen in the face of adult-onset PAH.

Given the congenital deficiency of elastin in our mice, we expected to see changes consistent with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN). However, our mice displayed no anatomical characteristics typical of PPHN. The high pulmonary vascular resistance in PPHN is ascribed, in part, to thickened PA walls and a narrowed arterial lumen (32), resulting from hyperplasia and hypertrophy of smooth muscle cells in the PA media (1, 9) and excess structural extracellular matrix proteins, like elastin, in the pulmonary media and adventitia (10). PA in our mice demonstrate the typical spindle-shaped phenotype of mature smooth muscle cells, decreased amounts of elastin, and structural remodeling characterized by preservation of the wall thickness-to-luminal diameter ratio (Table 2). Thus the remodeling in elastin insufficiency is fundamentally different than that seen in PPHN.

The present study has identified elastin gene dosage as a susceptibility factor for PAH. This predisposition is mediated by architectural and mechanical remodeling of the pulmonary vessels as a direct consequence of decreased vascular elastin content. The increased pulmonary pressures probably function to maintain vascular cross-sectional area and cardiac output. These findings differ considerably from what is observed in PPHN and adult-onset PAH in that the typical pulmonary vascular remodeling is absent (PPHN) or attenuated (adult-onset PAH), probably through physiological adaptation to congenital elastin insufficiency. Although PAH is not commonly described in SVAS (ELN+/−) patients, SVAS phenotypes demonstrate significant variability in their penetrance. In addition, the pathogenesis of PAH probably involves multiple environmentally and genetically mediated insults (18, 26, 50). Thus it is possible that decreased elastin levels, in isolation, are conducive, but not sufficient, for the development of PAH in humans. However, given the high penetrance of elevated pulmonary pressures in elastin-insufficient mice, PAH may be more common than currently appreciated in SVAS patients, a possibility that warrants further clinical investigation.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants HL53325, HL74138, and P50-HL084922 to R. P. Mecham, and American Lung Association Grant RT-9702-N to A. Shifren. Additional funding from NIH Grant T32GM00879 to A. Shifren is also acknowledged.

Acknowledgments

We thank Terese Hall for administrative assistance, Chris Ciliberto for animal care, and Jessica Wagenseil for helpful discussion.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen K, Haworth SG. Human postnatal pulmonary arterial remodeling. Ultrastructural studies of smooth muscle cell and connective tissue maturation. Lab Invest 59: 702–709, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briones AM, Gonzalez JM, Somoza B, Giraldo J, Daly CJ, Vila E, Gonzalez MC, McGrath JC, Arribas SM. Role of elastin in spontaneously hypertensive rat small mesenteric artery remodelling. J Physiol 552: 185–195, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown-Augsburger P, Tisdale C, Broekelmann T, Sloan C, Mecham RP. Identification of an elastin cross-linking domain that joins three peptide chains: possible role in nucleated assembly. J Biol Chem 270: 17778–17783, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brusselmans K, Compernolle V, Tjwa M, Wiesener MS, Maxwell PH, Collen D, Carmeliet P. Heterozygous deficiency of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha protects mice against pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction during prolonged hypoxia. J Clin Invest 111: 1519–1527, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chesler NC, Thompson-Figueroa J, Millburne K. Measurements of mouse pulmonary artery biomechanics. J Biomech Eng 126: 309–314, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chuong CJ, Fung YC. On residual stresses in arteries. J Biomech Eng 108: 189–192, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohn JN Arterial stiffness, vascular disease, and risk of cardiovascular events. Circulation 113: 601–603, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coulson RJ, Chesler NC, Vitullo L, Cipolla MJ. Effects of ischemia and myogenic activity on active and passive mechanical properties of rat cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H2268–H2275, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dakshinamurti S Pathophysiologic mechanisms of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Pediatr Pulmonol 39: 492–503, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durmowicz AG, Stenmark KR. Mechanisms of structural remodeling in chronic pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Rev 20: e91–e102, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyer K, Lanning C, Das B, Lee PF, Ivy DD, Valdes-Cruz L, Shandas R. Noninvasive Doppler tissue measurement of pulmonary artery compliance in children with pulmonary hypertension. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 19: 403–412, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eddahibi S, Hanoun N, Lanfumey L, Lesch KP, Raffestin B, Hamon M, Adnot S. Attenuated hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in mice lacking the 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter gene. J Clin Invest 105: 1555–1562, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Bizri N, Wang L, Merklinger SL, Guignabert C, Desai T, Urashima T, Sheikh AY, Knutsen RH, Mecham RP, Mishina Y, Rabinovitch M. Smooth muscle protein 22alpha-mediated patchy deletion of Bmpr1a impairs cardiac contractility but protects against pulmonary vascular remodeling. Circ Res 102: 380–388, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faury G, Maher GM, Li DY, Keating MT, Mecham RP, Boyle WA. Relation between outer and luminal diameter in cannulated arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H1745–H1753, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faury G, Pezet M, Knutsen RH, Boyle WA, Heximer SP, McLean SE, Minkes RK, Blumer KJ, Kovacs A, Kelly DP, Li DY, Starcher B, Mecham RP. Developmental adaptation of the mouse cardiovascular system to elastin haploinsufficiency. J Clin Invest 112: 1419–1428, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fung YC Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. New York: Springer, 1993.

- 17.Fung YC, Liu SQ. Changes of zero-stress state of rat pulmonary arteries in hypoxic hypertension. J Appl Physiol 70: 2455–2470, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansmann G, Wagner RA, Schellong S, Perez VA, Urashima T, Wang L, Sheikh AY, Suen RS, Stewart DJ, Rabinovitch M. Pulmonary arterial hypertension is linked to insulin resistance and reversed by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation. Circulation 115: 1275–1284, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirano E, Knutsen RH, Sugitani H, Ciliberto CH, Mecham RP. Functional rescue of elastin insufficiency in mice by the human elastin gene: implications for mouse models of human disease. Circ Res 101: 523–531, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang W, Yen RT. Zero-stress states of human pulmonary arteries and veins. J Appl Physiol 85: 867–873, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudetz AG Incremental elastic modulus for orthotropic incompressible arteries. J Biomech 12: 651–655, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kececioglu D, Kotthoff S, Vogt J. Williams-Beuren syndrome: a 30-year follow-up of natural and postoperative course. Eur Heart J 14: 1458–1464, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Land SD, Shah MD, Berman WF. Pulmonary hypertension associated with portal hypertension in a child with Williams syndrome–a case report. Pediatr Pathol 14: 61–68, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li DY, Faury G, Taylor DG, Davis EC, Boyle WA, Mecham RP, Stenzel P, Boak B, Keating MT. Novel arterial pathology in mice and humans hemizygous for elastin. J Clin Invest 102: 1783–1787, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Littler CM, Wehling CA, Wick MJ, Fagan KA, Cool CD, Messing RO, Dempsey EC. Divergent contractile and structural responses of the murine PKC-epsilon null pulmonary circulation to chronic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 289: L1083–L1093, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Machado RD, James V, Southwood M, Harrison RE, Atkinson C, Stewart S, Morrell NW, Trembath RC, Aldred MA. Investigation of second genetic hits at the BMPR2 locus as a modulator of disease progression in familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 111: 607–613, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahapatra S, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, Cha S, McGoon MD. Relationship of pulmonary arterial capacitance and mortality in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 47: 799–803, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malvern LE Introduction to the Mechanics of a Continuous Medium. Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969.

- 29.Maruyama K, Ye CL, Woo M, Venkatacharya H, Lines LD, Silver MM, Rabinovitch M. Chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in rats and increased elastolytic activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H1716–H1726, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto T, Hayashi K. Stress and strain distribution in hypertensive and normotensive rat aorta considering residual strain. J Biomech Eng 118: 62–73, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald AH, Gerlis LM, Somerville J. Familial arteriopathy with associated pulmonary and systemic arterial stenoses. Br Heart J 3: 375–385, 1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLeod KA, Gerlis LM, Williams GJ. Morphology of the elastic pulmonary arteries in pulmonary hypertension: a quantitative study. Cardiol Young 9: 364–370, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mecham RP, Whitehouse LA, Wrenn DS, Parks WC, Griffin GL, Senior RM, Crouch EC, Stenmark KR, Voelkel NF. Smooth muscle-mediated connective tissue remodeling in pulmonary hypertension. Science 237: 423–426, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merklinger SL, Wagner RA, Spiekerkoetter E, Hinek A, Knutsen RH, Kabir MG, Desai K, Hacker S, Wang L, Cann GM, Ambartsumian NS, Lukanidin E, Bernstein D, Husain M, Mecham RP, Starcher B, Yanagisawa H, Rabinovitch M. Increased fibulin-5 and elastin in S100A4/Mts1 mice with pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res 97: 596–604, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pober BR, Johnson M, Urban Z. Mechanisms and treatment of cardiovascular disease in Williams-Beuren syndrome. J Clin Invest 118: 1606–1615, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reesink HJ, Henneman OD, van Delden OM, Biervliet JD, Kloek JJ, Reekers JA, Bresser P. Pulmonary arterial stent implantation in an adult with Williams syndrome. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 30: 782–785, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenbloom J, Abrams WR, Mecham R. Extracellular matrix 4: the elastic fiber. FASEB J 7: 1208–1218, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Safar ME, Levy BI, Struijker-Boudier H. Current perspectives on arterial stiffness and pulse pressure in hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Circulation 107: 2864–2869, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Said SI, Hamidi SA, Dickman KG, Szema AM, Lyubsky S, Lin RZ, Jiang YP, Chen JJ, Waschek JA, Kort S. Moderate pulmonary arterial hypertension in male mice lacking the vasoactive intestinal peptide gene. Circulation 115: 1260–1268, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shadwick RE Mechanical design in arteries. J Exp Biol 202: 3305–3313, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shifren A, Durmowicz AG, Knutsen RH, Hirano E, Mecham RP. Elastin Protein Levels are a Vital Modifier Affecting Normal Lung Development and Susceptibility to Emphysema. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L778–L787, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stenmark KR, Fagan KA, Frid MG. Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Circ Res 99: 675–691, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stenmark KR, Mecham RP. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pulmonary vascular remodeling. Annu Rev Physiol 59: 89–144, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steudel W, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Bloch KD, Weimann J, Huang PL, Jones RC, Picard MH, Zapol WM. Sustained pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy after chronic hypoxia in mice with congenital deficiency of nitric oxide synthase 3. J Clin Invest 101: 2468–2477, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Urban Z, Michels VV, Thibodeau SN, Davis EC, Bonnefont JP, Munnich A, Eyskens B, Gewillig M, Devriendt K, Boyd CD. Isolated supravalvular aortic stenosis: functional haploinsufficiency of the elastin gene as a result of nonsense-mediated decay. Hum Genet 106: 577–588, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vito RP, Dixon SA. Blood vessel constitutive models–1995–2002. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 5: 413–439, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagenseil JE, Nerurkar NL, Knutsen RH, Okamoto RJ, Li DY, Mecham RP. Effects of elastin haploinsufficiency on the mechanical behavior of mouse arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H1209–H1217, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinberg CE, Hertzberg JR, Ivy DD, Kirby KS, Chan KC, Valdes-Cruz L, Shandas R. Extraction of pulmonary vascular compliance, pulmonary vascular resistance, and right ventricular work from single-pressure and Doppler flow measurements in children with pulmonary hypertension: a new method for evaluating reactivity: in vitro and clinical studies. Circulation 110: 2609–2617, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wren C, Oslizlok P, Bull C. Natural history of supravalvular aortic stenosis and pulmonary artery stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 15: 1625–1630, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan JX, Rubin LJ. Pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension: the need for multiple hits. Circulation 111: 534–538, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zaidi SH, You XM, Ciura S, Husain M, Rabinovitch M. Overexpression of the serine elastase inhibitor elafin protects transgenic mice from hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 105: 516–521, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zieman SJ, Melenovsky V, Kass DA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and therapy of arterial stiffness. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 932–943, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]