Abstract

Although the general radiobiologic principles underlying external beam therapy and radionuclide therapy are the same, there are significant differences in the biophysical and radiobiologic effects from the two types of radiation. In addition to the emission of particulate radiation, targeted radionuclide therapy is characterized by (i) extended exposures and, usually, declining dose rates; (ii) nonuniformities in the distribution of radioactivity and, thus, absorbed dose; and (iii) particles of varying ionization density and, hence, quality. This chapter explores the special features that distinguish the biologic effects consequent to the traversal of charged particles through mammalian cells. It also highlights what has been learned when these radionuclides and radiotargeting pharmaceuticals are used to treat cancers.

Keywords: alpha-particle emitters, Auger-electron emitters, beta-particle emitters, radiobiology, radionuclide therapy

INTRODUCTION

For almost a hundred years, the scientific and medical communities have used radionuclides for therapy. The hopes for employing unsealed sources, however, are still mainly unrealized. The problem has three components. The first is the availability of radionuclides with appropriate physical properties. The second involves the interaction between the radionuclide and its biologic environment, i.e., the radiation biology of the decaying moiety. The third is the identification of carrier molecules with which to target such radionuclides to tumors. In the case of the radionuclide, one must consider its mode of decay, including the nature of the particulate radiations and their energies, its physical half-life, and its chemistry in relation to the carrier molecule. In the case of the carrier, one must define its stability and specificity; the biologic mechanisms that will bind it to the targeted cells, including the number of accessible sites and the affinity of the carrier to these sites, the stability of the receptor–carrier-molecule complex, the distribution of the sites among cells (both target and nontarget), the relationship of site appearance to the cell cycle, and the microenvironment of the target (for a tumor, its vascularity, vascular permeability, oxygenation, microscopic organization and architecture, including the mobility of the cells, their location and accessibility to intralymphatic, intraperitoneal, intracerebral and intramedullary routes). In addition, the outcome is dependent upon certain biologic responses that are outlined below.

In this chapter, both the special features that characterize the biologic effects consequent to the traversal of charged particles through mammalian cells and the state of knowledge concerning the use of these radionuclides to treat cancers will be emphasized. The current status of radionuclide-based therapies will also be reviewed.

PARTICULATE RADIATION

Energetic Particles

In general, the distribution of therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals within a targeted solid tumor is not homogeneous. This is mainly a result of (i) the inability of the radiolabeled molecules to penetrate uniformly dissimilar regions within a solid tumor mass: (ii) the high interstitial pressure of solid tumors; and/or (iii) differences in the binding-site densities of tumor cells. In the case of radiopharmaceuticals labeled with energetic alpha-particle and beta-particle emitters (range of emitted particle >> than diameter of the targeted cell), such nonuniformity will lead to dosimetric nonhomogeneities, i.e., major differences in the absorbed doses to individual tumor cells. Consequently, the mean absorbed dose is less likely to be a good predictor of radiotherapeutic efficacy.

Alpha-particle emitters

Over the past 40 years, the therapeutic potential of several alpha-particle-emitting radionuclides has been assessed. These particles (i) are positively charged with a mass and charge equal to that of the helium nucleus, their emission leading to a daughter nucleus that has two fewer protons and two fewer neutrons (Figure 1); (ii) have energies ranging from 5 to 9 MeV and corresponding tissue ranges of approximately five mammalian-cell diameters (Table 1); and (iii) travel in straight lines. The linear energy transfer (LET, in keV/µm, which reflects energy deposition and, therefore, ionization density along the track of a charged particle) of these energetic and doubly charged (+2) particles is very high (~80–100 keV/µm) along most of their up-to-100-µm path before increasing to ~300 keV/µm toward the end of the track (Bragg peak) (Figure 2). Consequently, in the case of cell irradiation, the therapeutic efficacy of alpha-particle emitters depends on (i) distance of the decaying atom from the targeted mammalian cell nucleus – vis-à-vis the probability of a nuclear traversal (Figure 3); and (ii) role of heavy ion recoil of the daughter atom, in particular when the alpha-particle emitter is covalently bound to nuclear DNA (1). Of equal importance are the contribution(s) from bystander effects and the magnitude of cross-dose (from radioactive sources associated with one cell to an adjacent/nearby cell – see below) as this will vary considerably depending on the size of the labeled cell cluster and the fraction of cells labeled (2) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of emissions produced during decay of therapeutic radionuclides.

Table 1.

General characteristics of therapeutic radionuclides.

| Decay | Particles (#)I | E(min)–E(max) | Range | LET |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α++-particle | He nuclei (1) | 5–9 MeVH | 40–100 µm | ~80 keV/µm |

| β−-particle | Energetic electrons (1) | 50–2,300 keV* | 0.05–12 mm | ~0.2 keV/µm |

| EC/IC | Nonenergetic electrons (5–30) | eV–keVH | 2–500 nm | ~4–26 KeV/µm |

Number of particles emitted per decaying atom.

Monoenergetic.

Average (>1% intensity); continuous distribution of energy.

FIGURE 2.

Ionization density along path of alpha particle as function of traversed distance.

FIGURE 3.

Number of radioactive atoms required to ensure traversal of cell nucleus by one energetic particle as function of distance from center of cell. Nuclear radius to distance of decaying atom (percentage) is plotted as function of number of decays (N). Rc: cell radius; Rn: nuclear radius; Dd: distance of decaying atom from center of cell for one nuclear traversal. Note that (i) nuclear localization of radioactive atom is the only condition that will lead to one traversal per decaying atom; (ii) when decaying atoms are on nuclear membrane, ≥2 radioactive atoms are needed for one nuclear traversal; and (iii) when decaying atoms are localized on cell membrane and diameter of cell is twice that of nucleus, >15 radioactive atoms are necessary to ensure one nuclear traversal.

Beta-particle emitters

Beta particles are negatively charged electrons emitted from the nucleus of decaying radioactive atoms (one electron/decay), that have various energies (zero up to a maximum) and, thus, a distribution of ranges (Table 1). After their emission, the daughter nucleus has one more proton and one less neutron (Figure 1). As these beta particles traverse matter, they lose their kinetic energies and eventually follow a contorted path and come to a stop. Because of their small mass, the recoil energy of the daughter nucleus is negligible. Additionally, the LET of these energetic and negatively (−1) charged particles is very low (~0.2 keV/µm) along their up-to-a-centimeter path (i.e., they are sparsely ionizing), except for the few nanometers at the end of the range (Figure 4). Consequently, their therapeutic efficacy predicates the presence of very high radionuclide concentrations within the targeted tissue. The long range of these emitted electrons leads to the production of cross-fire, a circumstance that negates the need to target every cell within the tumor, so long as all the cells are within the range of the decaying atoms. As with alpha particles, the probability of the emitted beta particle’s traversing the targeted cell nucleus depends to a large degree on (i) the position of the decaying atom vis-à-vis the nucleus – specifically nuclear DNA – of the targeted tumor cell; (ii) its distance from the tumor cell nucleus; and (iii) the radius of the latter (Figure 3). Obviously, intranuclear localization of therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals is highly advantageous and, if possible, should always be sought.

FIGURE 4.

Linear energy transfer (LET) along paths of energetic beta particles and Auger electrons as function of traversed distance.

Nonenergetic Particles

During the decay of many radioactive atoms, a vacancy is formed (most commonly in the K shell) as a consequence of electron capture (EC) and/or internal conversion (IC) (Figure 1). Each of these vacancies is rapidly filled by an electron dropping in from a higher shell. The process leads to a cascade of atomic electron transitions that move the vacancy toward the outermost shell. These inner-shell electron transitions result in the emission of characteristic X-ray photons or an Auger, Coster-Kronig, or super Coster-Kronig monoenergetic electron (collectively called Auger electrons). Typically, an average of 5 to 30 Auger electrons – with energies ranging from a few eV to approximately 1 keV – are emitted per decaying atom (3). In addition to producing low-energy electrons, this form of decay leaves the daughter atom with a high positive charge resulting in subsequent charge-transfer processes. The very low energies of Auger electrons have two major consequences: (i) these light, negatively (−1) charged particles travel in contorted paths and their range in water is from a fraction of a nanometer up to ~0.5 µm (Table 1); and (ii) multiple ionizations (LET: 4–26 keV/µm) occur in the immediate vicinity (few nanometers) of the decay site (Figure 4) (4), reminiscent of those observed along the path of an alpha particle (3). Finally, the short range of Auger electrons necessitates their close proximity to the radiosensitive target (DNA) for radiotherapeutic effectiveness (Table 1). This is essentially a consequence of the precipitous drop in energy density as a function of distance in nanometers (5–7).

RADIOBIOLOGY

The deposition of energy by ionizing radiation in mammalian cells is a random process. The absorption of energy in such cells can induce certain molecular modifications that may lead to cell death. Even though this process is stochastic in nature, the death of a few cells within a tissue or an organ will not have, in general, a significant effect on function. However, as the dose increases, more cells will die with the eventual impairment of tissue/organ function (8).

Molecular lesions

DNA is the principal target responsible for radiation-induced biologic effects. A number of different lesions occur (e.g., single-strand breaks [SSB], double-strand breaks [DSB], base damage, DNA–protein cross-links, multiply damaged sites [MDS]). These changes may be produced by the direct ionization of DNA (direct effect) or by the interaction of free radicals with DNA (indirect effect, mostly hydroxyl radicals produced in water molecules that diffuse several nanometers). Most of these lesions are repaired with high fidelity, the exceptions being DSB and MDS.

The distribution of ionizations within DNA and the type of damage created depend upon the nature of the incident particle and its energy. Alpha particles produce a high density along a linear path (Figure 5, bottom); energetic beta particles, infrequent ionizations along a linear path (Figure 5, top); low-energy electrons, frequent ionizations along an irregular path; and Auger cascades, clusters of high ionization density (Figure 5, center). Double-strand breaks generated by high specific ionization (e.g., alpha particles and Auger-electron cascades) are less reparable than SSBs (e.g., created by more sparsely ionizing radiation).

FIGURE 5.

Schematic representation of ionization densities produced along tracks of energetic beta particles, Auger electrons, and alpha particles.

Cellular responses

Clonal survival

When mammalian cells are acutely exposed (high dose rate) to ionizing radiation, their ability to divide indefinitely declines as a function of radiation dose. The shape of the survival curve (Figure 6) depends on the density of ionizations. For densely ionizing radiation (alpha particles and Auger-electron cascades), the logarithmic response is linear (−lnSF = αD), where SF is the survival fraction, α is the slope, and D is the absorbed dose. For sparse irradiation, the logarithmic response is linear-quadratic (!lnSF = αD + βD2), where α is the rate of cell kill by a single-hit mechanism, D is the dose delivered, and β equals the rate of cell kill by a double-hit mechanism (the βD2 term is thought to represent accumulated and reparable damage). This type of survival curve is routinely observed when mammalian cells are exposed to low-LET radiation (e.g., photons, energetic beta particles, extranuclear Auger electrons). When the dose rate is low, as often occurs with radionuclides, the α term predominateṣ. It is important to note that the α-to-β ratio represents the dose at which cell killing by the linear and quadratic components is equal, i.e. when αD = βD2 (D = α/β).

FIGURE 6.

Mammalian cell survival curves after high- and low-LET irradiation. With high-LET radiation (alpha and nonenergetic electrons), curve shows exponential decrease in survival; with low-LET radiation (energetic electrons), curve exhibits a shoulder.

Because sparsely ionizing radiation produces reparable sublethal damage, both the shape of the dose–response curve and the acuteness of the slope are sensitive to dose rate. Consequently, lower dose rates are less damaging than higher ones. In radionuclide therapy this is particularly important when the physical half-life of the isotope is somewhat long. Thus, as with fractionated external beam therapy, the total dose from continuous low-dose radionuclide therapy is less effective than a single dose of the same magnitude, i.e., for a comparable biologic effect, a larger dose is required (9).

Whereas it is clear that radionuclides whose decay results in a purely exponential decrease in cell survival (every decay leads to a corresponding decrease in survival) are preferable for radiotherapy, the exponential nature of linear and linear-quadratic survival curves has important implications. In essence, it indicates that only very high doses will reduce the number of viable cancer cells in a macroscopic tumor to less than one. Therefore, no dose will be sufficiently large to eradicate 100% of the clonogenic cells with certainty, especially since it will always be limited by normal tissue tolerance.

Division delay and programmed cell death

Irradiation of dividing mammalian cells leads to a delay in their progression through their cell cycle. However, this delay is reversible and its length is dose-dependent. Furthermore, it occurs only at specific points in the cell cycle and is similar for both surviving and nonsurviving cells: maximum delay is observed when premitotic G2 cells are irradiated, little delay is seen in G1 cells, moderate delay in S cells, and cells in mitosis continue through division basically undisturbed. Consequently, the irradiation of such dividing mammalian cells leads to their accumulation at the G2/M boundary and a change in their mitotic index.

Division delay allows irradiated cells time to determine their fate. When cells are irradiated and DNA is damaged, the damage is sensed and various genes are activated. Cells held at checkpoints await repair of DNA, and then proceed through the cell cycle. Alternatively, damage may be nonreparable, and the cells are induced to undergo programmed cell death or apoptosis. However, since not all cells are born equal, the apoptotic response is varied. For example, lymphoid tumor cells are more likely to undergo apoptosis than epithelial cells. This may account for the success of radioimmunotherapy in certain lymphomas, whereas, in epithelial cells, apoptosis appears to account for only a small portion of clonal cell death.

Oxygen enhancement ratios

It is well known that oxygen radiosensitizes mammalian cells to the damaging effects of radiation. Hypoxic cells can be up to threefold more radioresistant than well-oxygenated cells, because oxygen enhances free radical formation and/or it may block reversible and reparable chemical alterations. The oxygen effect is maximal for low-ionization-density radiation (photons and high-energy beta particles) and minimal for high-LET radiation (alpha particles, low-energy electrons including Auger-electron cascades). In the former instance, the presence of hypoxic regions within tumors is believed to be a major cause of radiotherapeutic failure.

Bystander effect

Radiation-induced bystander effects refer to biologic responses occurring in cells that are not traversed by an ionizing radiation track and, thus, are not subject to energy deposition events, i.e., the response(s) take place in unirradiated cells. As such, these bystander effects are somehow communicated from an irradiated cell to an unirradiated cell, via cell-to-cell gap junction communication (10) and/or by the secretion or shedding of soluble factors whose precise nature is unknown, although reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and various cytokines have been implicated (11–15).

Originally observed with external alpha-particle beams in vitro, the phenomenon has also been observed in subcutaneous tumors (14, 16, 17). These observations have negated a central tenet of radiobiology that damage to cells is caused only by direct ionizations and/or by free radicals generated as a consequence of the deposition of energy within the nuclei of mammalian cells. The importance of the bystander effect as an enhancer of radiotherapeutic efficacy is yet to be determined.

Self-dose, cross-fire, and nonuniform dose distribution

When radionuclides are employed for therapy, cells may be irradiated by decays taking place on or within the targeted cells (self-dose) or in neighboring or distant cells (cross-fire). Because of geometric factors (Figure 3), the self-dose from energetic alpha and beta particles is very dependent on their position on or within the tumor cell, whereas that from Auger-electron emitters depends mainly on the proximity of the decaying atom to DNA.

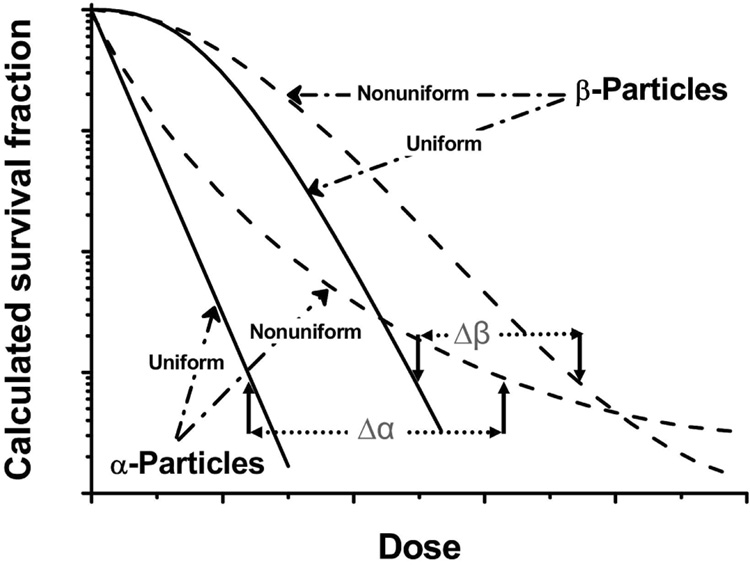

In targeted radionuclide therapy, the distribution of radioactivity and, hence, the absorbed dose tend to be nonuniform. Consequently, higher doses are required to sterilize targeted cells. Humm (18, 19) has calculated that the difference in dose needed for a similar decrease in survival fraction with uniform and nonuniform dose distributions of alpha-particle-emitting radionuclides is greater (Δα > Δβ) than that for energetic beta particles (Figure 7). O’Donoghue (20) also has described a mathematical model that examines the impact of dose nonuniformity and dose-rate effects on therapeutic response. This model predicts that (i) a nonuniform dose distribution grows proportionately less effective as the absorbed dose increases; (ii) the surviving fraction increases for any mean absorbed dose as the absorbed dose distribution becomes less uniform; and (iii) the difference in survival fraction – consequent to a uniform versus nonuniform dose – is more pronounced as the radiosensitivity of tumor cells increases.

FIGURE 7.

Schematic representation of relationship between mammalian cell survival and alpha- and beta-particle-emitter distribution as function of dose. Solid lines: uniform irradiation; broken lines: nonuniform irradiation.

Half-life

Because many biologic responses to radiation are sensitive to dose rate as well as total dose, the physical half-life (T1/2P) of the radionuclide employed and the tumor and normal tissue biological half-life (T1/2B) affect the response of the tumor. For a radiopharmaceutical with an infinite residence time in a tumor, a radionuclide with a long physical half-life will deliver more decays than one with a short half-life if both have the same initial radioactivity. There is also a striking difference in the time-dependent dose rate delivered by the two. For example, if the number of radionuclide atoms per unit of tumor mass is n and the energy emitted (and absorbed) per decay is E, then the absorbed-dose rate is proportional to nE/T where T is the half-life. The ratio E/T is an important indicator of the intrinsic radiotherapeutic potency of the radionuclide (21). From a radiobiologic standpoint, higher dose rates delivered over shorter treatment times are more effective than lower dose rates delivered over longer periods. Thus, a radionuclide with a shorter half-life will tend to be more biologically effective than one with a similar emission energy but longer half-life.

EXPERIMENTAL THERAPEUTICS

Energetic particle emitters

Alpha emitters

The application of alpha-particle-emitting radionuclides as targeted therapeutic agents continues to be of interest. When such radionuclides are selectively accumulated in the targeted tissues (e.g., tumors), their decay should result in highly localized energy deposition in the tumor cells and minimal irradiation of surrounding normal host tissues.

The investigation of the therapeutic potential of alpha-particle emitters has focused mainly on five radionuclides: astatine-211 (211At), bismuth-212 (212Bi), bismuth-213 (213Bi), radium-223 (223Ra), and actinium-225 (225Ac) (Table 2). In vitro studies (24, 25) have shown that the decrease in mammalian cell survival after exposure to uniformly distributed alpha particles from such radionuclides is monoexponential but that, as predicted theoretically (19) and shown experimentally (1), these curves develop a tail when the dose is nonuniform (Figure 7). Such studies have also indicated that the traversal of one to four of these high-LET alpha particles through a mammalian cell nucleus will kill the cell (1, 24, 25). In comparison, since the LET of negatrons emitted by the decay of energetic beta emitters used for tumor therapy is ~0.2 keV/µm (Figure 4), thousands of beta particles must traverse a cell nucleus for its sterilization (26).

Table 2.

Alpha-particle emitters: physical properties.

The therapeutic potential of alpha-particle emitters in tumor-bearing animals has also been assessed (27–31). For example, Bloomer and co-workers (27) have reported a dose-related prolongation in median survival when mice bearing an intraperitoneal murine ovarian tumor are treated with 211At-tellurium colloid administered directly into the peritoneal cavity. Whereas this alpha-particle-emitting radiocolloid is curative without serious morbidity, beta-particle-emitting radiocolloids (phosphorus-32, dysprosium-165, yttrium-90) are much less efficacious. In another set of in vivo studies examining the therapeutic efficacy of 225Ac-labeled internalizing antibodies, McDevitt and co-workers (32) have demonstrated the therapeutic efficacy of 213Bi-labeled internalizing antibodies in mice bearing solid prostate carcinoma or disseminated lymphoma.

Beta emitters

Historically, studies of radionuclide-based tumor therapy have been carried out mainly with energetic beta-particle emitters. The exposure of cells in vitro to beta particles leads, in general, to survival curves that have a distinct shoulder and a D0 of several thousand decays (26, 33). Despite the rather low in vitro cytotoxicity, these radionuclides continue to be pursued for targeted therapy, mainly due to their availability and favorable physical characteristics (e.g., energy and range of the emitted electrons leading to cross-fire irradiation; physical half-lives compatible with the biologic half-lives of the carrier molecules) (Table 3). As mentioned above, the main advantage of cross-fire is that it negates the necessity of the radiotherapeutic agent’s being present within each of the targeted cells, i.e., it counteracts a certain degree of heterogeneity. Since the ionization densities of energetic electrons are low, however, the delivery of an effective therapeutic dose to the targeted tissue necessitates that (i) the distances between these foci are equal to or less than twice the maximum range of the emitted energetic beta particles; and (ii) the concentration of the radiotherapeutic agent within each focus is sufficiently high to produce a cumulative cross-fire dose of ~10,000 cGy to all the targeted cells. Since dose is inversely proportional to the square of distance, the concentration of the therapeutic agent needed to deposit such cytocidal doses rises many fold with an increase in nonuniform, radionuclide distribution.

Table 3.

Beta-particle emitters: physical properties.

Experimentally, investigators have assessed the therapeutic efficacy of 131I-labeled monoclonal antibodies in small tumor-bearing rodents. These studies have shown that when such radiopharmaceuticals localize in high concentrations within solid tumors, they are therapeutically quite efficacious (34). Thus, even when iodine-131 is not-so-uniformly distributed within a tumor, the decay of this radionuclide can lead to sterilization of small tumors in mice so long as it is present in sufficiently high concentrations. Similar results have been reported with radiopharmaceuticals labeled with other beta-particle-emitting isotopes, in particular yttrium-90 (35–37) and copper-67 (38). An important outcome of these findings has been the introduction of 131I- and 90Y-labeled antibodies in the clinic.

Low energy electron emitters

The therapeutic potential of radionuclides that decay by EC and/or IC has been established, for the most part, with iodine-125. Studies with this and other Auger-electron-emitting radionuclides (Table 4) have shown that (i) multiple electrons are emitted per decaying atom; (ii) the distances traversed by these electrons are mainly in the nanometer range; (iii) the LET of the electrons is >20-fold higher than that observed along the tracks of energetic (>50 keV) beta particles (Figure 4); and (iv) many of the emitted electrons dissipate their energy in the immediate vicinity of the decaying atom and deposit 106 to 109 rad/decay within a few-nanometer sphere around the decay site (3). From a radiobiologic prospective, the tridimensional organization of chromatin within the mammalian cell nucleus involves many structural level compactions (e.g., nucleosome, 30-nm chromatin fiber, chromonema fiber) whose dimensions are within the range of these high-LET (4–26 keV/µm), low-energy (≤1.6 keV), short-range (≤150 nm) electrons. Therefore, the toxicity of Auger-emitting radionuclides is expected to depend critically on close proximity of the decaying atom to DNA and to be quite high. These predictions are substantiated by in vitro studies showing that (i) the decay of Auger-electron emitters covalently bound to nuclear DNA leads to monoexponential decreases in survival (6, 39); (ii) the curves may or may not exhibit a shoulder when the decaying atoms are not covalently bound to nuclear DNA (40–42); and (iii) in general, intranuclear decay accumulation is highly toxic (D0 = ~100–500 decays/cell), whereas decay within the cytoplasm or extracellularly produces no extraordinary lethal effects and these survival curves resemble those observed with X-ray (have a distinct shoulder) (3).

Table 4.

Auger-electron emitters: physical properties.

| Total electron yield per decay | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radionuclide (#*) | Half-life | “Long” range electrons (%) | “Short” range electrons (%) | “Very short” range electrons (%) |

| 125I (20) | 60.5 d | 20 (98%) | 18 (86%) | 8 (39%) |

| 123I (11) | 13.3 h | 11 (98%) | 10 (89%) | 5 (40%) |

| 77Br (7) | 57 h | 7 (100%) | 6 (95%) | 3 (51%) |

| 111In (15) | 3 d | 15 (98%) | 14 (91%) | 8 (53%) |

| 195mPt (36) | 4 d | 33 (92%) | 33 (79%) | 7 (19%) |

| Range: | <0.5 µm | <100 nm | <2 nm | |

| LETH: | 4–26 | 9–26 | <18 | |

Average number of electrons emitted/decay.

Fit of data by Cole (4).

The radiotoxicity of the Auger-electron emitter iodine-125 has been compared with that of the energetic beta-particle emitter iodine-131 (26) in mammalian cells in vitro. Unlike the low-LET type of survival curve (with shoulder) obtained following the decay of beta-emitting iodine-131 in DNA, a high-LET curve (with no shoulder) is observed with iodine-125. Additionally, the slope of the latter curve is much steeper than that of the former. In contrast, the decay of iodine-125 in the cytoplasm is much less (~80-fold) efficient at cell killing (41). Constantini et al. (43) have modified a monoclonal antibody with a nuclear localization peptide sequence, labeled it with indium-111, and have shown a sixfold enhancement in the radiotoxicity of the antibody to breast cancer cells. Reske and co-workers (44) have demonstrated the inhibition of thymidylate synthetase, following pretreatment with the antimetabolite fluorodeoxyuridine, leads to a 20-fold increase in radiotoxicity of the 123I-labeled thymidine analog iodothiodeoxythymidine. Earlier in vitro and in vivo (tumor-bearing rats and cancer patients) studies had similarly shown enhanced uptake and toxicity of 123IUdR and 125IUdR by tumors cells (45, 46). Such results support the notion that the biologic effects of an Auger-electron emitter are strongly dependent on its intracellular localization, in particular its proximity to DNA.

The extreme degree of cytotoxicity observed with DNA-incorporated Auger-electron emitters has been exploited in experimental radionuclide therapy. In most of these in vivo studies, the thymidine analog 5-iodo-2’-deoxyuridine (IUdR) has been used (45, 47, 48), and the findings have shown excellent therapeutic efficacy. For example, the injection of 125IUdR into mice bearing an intraperitoneal ascites ovarian cancer has led to a 5-log reduction in tumor cell survival (47). Similar findings occur with 123IUdR (48). Therapeutic doses of 125IUdR injected intrathecally into rats with intrathecal tumors significantly delay the onset of paralysis, as exemplified by a 5–6-log tumor cell kill and the curing of ~30% of the tumor-bearing rats (45).

CONCLUSIONS

The increase in our understanding of the dosimetry and the therapeutic potential of various modes of radioactive decay has heightened the possibility of utilizing radiolabeled carriers in cancer therapy. Moreover, as a consequence of the great strides in genomics, the development of more precise targeting molecules is at hand. Further progress in the field of targeted radionuclide therapy is being made by the judicious design of radiolabeled molecules that match the physical and chemical characteristics of both the radionuclide and the carrier molecule with the clinical character of the tumor.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This article was supported by NIH, 5 R01 CA15523.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- 1.Walicka MA, Vaidyanathan G, Zalutsky MR, Adelstein SJ, Kassis AI. Survival and DNA damage in Chinese hamster V79 cells exposed to alpha particles emitted by DNA-incorporated astatine-211. Radiat Res. 1998;150:263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goddu SM, Howell RW, Rao DV. Cellular dosimetry: absorbed fractions for monoenergetic electron and alpha particle sources and S-values for radionuclides uniformly distributed in different cell compartments. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:303–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassis AI. The amazing world of Auger electrons. Int J Radiat Biol. 2004;80:789–803. doi: 10.1080/09553000400017663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole A. Absorption of 20-eV to 50,000-eV electron beams in air and plastic. Radiat Res. 1969;38:7–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kassis AI, Adelstein SJ, Haydock C, Sastry KSR. Radiotoxicity of 75Se and 35S: theory and application to a cellular model. Radiat Res. 1980;84:407–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassis AI, Adelstein SJ, Haydock C, Sastry KSR, McElvany KD, Welch MJ. Lethality of Auger electrons from the decay of bromine-77 in the DNA of mammalian cells. Radiat Res. 1982;90:362–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kassis AI, Sastry KSR, Adelstein SJ. Intracellular localisation of Auger electron emitters: biophysical dosimetry. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 1985;13:233–236. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kassis AI, Adelstein SJ. Does nonuniformity of dose have implications for radiation protection? J Nucl Med. 1992;33:384–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barendsen GW. LET dependence of linear and quadratic terms in dose-response relationships for cellular damage: correlations with the dimensions and structures of biological targets. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 1990;31:235–239. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azzam EI, de Toledo SM, Little JB. Direct evidence for the participation of gap junction-mediated intercellular communication in the transmission of damage signals from α-particle irradiated to nonirradiated cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:473–478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011417098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narayanan PK, Goodwin EH, Lehnert BE. α particles initiate biological production of superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide in human cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3963–3971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narayanan PK, LaRue KEA, Goodwin EH, Lehnert BE. Alpha particles induce the production of interleukin-8 by human cells. Radiat Res. 1999;152:57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iyer R, Lehnert BE. Factors underlying the cell growth-related bystander responses to α particles. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1290–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kishikawa H, Wang K, Adelstein SJ, Kassis AI. Inhibitory and stimulatory bystander effects are differentially induced by iodine-125 and iodine-123. Radiat Res. 2006;165:688–694. doi: 10.1667/RR3567.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sgouros G, Knox SJ, Joiner MC, Morgan WF, Kassis AI. MIRD continuing education: Bystander and low–dose-rate effects: are these relevant to radionuclide therapy? J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1683–1691. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.105.028183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xue LY, Butler NJ, Makrigiorgos GM, Adelstein SJ, Kassis AI. Bystander effect produced by radiolabeled tumor cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13765–13770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182209699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyd M, Ross SC, Dorrens J, et al. Radiation-induced biologic bystander effect elicited in vitro by targeted radiopharmaceuticals labeled with α-, β-, and Auger electron–emitting radionuclides. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1007–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humm JL, Cobb LM. Nonuniformity of tumor dose in radioimmunotherapy. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:75–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humm JL, Chin LM, Cobb L, Begent R. Microdosimetry in radioimmunotherapy. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 1990;31:433–436. [Google Scholar]

- 20.ICRU. Absorbed-dose specification in nuclear medicine (ICRU Report 67) J ICRU. 2002;2(1):1–110. [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Donoghue JA. The impact of tumor cell proliferation in radioimmunotherapy. Cancer. 1994;73:974–980. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940201)73:3+<974::aid-cncr2820731333>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kocher DC. Radioactive decay data tables: a handbook of decay data for application to radiation dosimetry and radiological assessments. Vol DOE/TIC-11026. Springfield, Virginia: National Technical Information Center, US Department of Energy; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 23.ICRU. Stopping powers and ranges for protons and alpha particles, Report 49. Bethesda, Maryland: International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kassis AI, Harris CR, Adelstein SJ, Ruth TJ, Lambrecht R, Wolf AP. The in vitro radiobiology of astatine-211 decay. Radiat Res. 1986;105:27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlton DE, Kassis AI, Adelstein SJ. A comparison of experimental and calculated survival curves for V79 cells grown as monolayers or in suspension exposed to alpha irradiation from 212Bi distributed in the growth medium. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 1994;52:311–315. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan PC, Lisco E, Lisco H, Adelstein SJ. The radiotoxicity of iodine-125 in mammalian cells. II. A comparative study on cell survival and cytogenetic responses to 125IUdR, 131IUdR, and 3HTdR. Radiat Res. 1976;67:332–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bloomer WD, McLaughlin WH, Neirinckx RD, et al. Astatine-211–tellurium radiocolloid cures experimental malignant ascites. Science. 1981;212:340–341. doi: 10.1126/science.7209534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macklis RM, Kinsey BM, Kassis AI, et al. Radioimmunotherapy with alpha-particle–emitting immunoconjugates. Science. 1988;240:1024–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.2897133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zalutsky MR, McLendon RE, Garg PK, Archer GE, Schuster JM, Bigner DD. Radioimmunotherapy of neoplastic meningitis in rats using an α-particle-emitting immunoconjugate. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4719–4725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDevitt MR, Barendswaard E, Ma D, et al. An α-particle emitting antibody ([213Bi]J591) for radioimmunotherapy of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6095–6100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballangrud ÅM, Yang W-H, Charlton DE, et al. Response of LNCaP spheroids after treatment with an α-particle emitter (213Bi)-labeled anti-prostate-specific membrane antigen antibody (J591) Cancer Res. 2001;61:2008–2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDevitt MR, Ma D, Lai LT, et al. Tumor therapy with targeted atomic nanogenerators. Science. 2001;294:1537–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.1064126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burki HJ, Koch C, Wolff S. Molecular suicide studies of 125I and 3H disintegration in the DNA of Chinese hamster cells. Curr Top Radiat Res Q. 1977;12:408–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Esteban JM, Schlom J, Mornex F, Colcher D. Radioimmunotherapy of athymic mice bearing human colon carcinomas with monoclonal antibody B72.3: histological and autoradiographic study of effects on tumors and normal organs. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:643–655. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(87)90259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otte A, Mueller-Brand J, Dellas S, Nitzsche EU, Herrmann R, Maecke HR. Yttrium-90-labelled somatostatin-analogue for cancer treatment. Lancet. 1998;351:417–418. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)78355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chinn PC, Leonard JE, Rosenberg J, Hanna N, Anderson DR. Preclinical evaluation of 90Y-labeled anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody for treatment of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Int J Oncol. 1999;15:1017–1025. doi: 10.3892/ijo.15.5.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Axworthy DB, Reno JM, Hylarides MD, et al. Cure of human carcinoma xenografts by a single dose of pretargeted yttrium-90 with negligible toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1802–1807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeNardo GL, Kukis DL, DeNardo SJ, et al. Enhancement of 67Cu-2IT-BAT-Lym-1 therapy in mice with human Burkitt's lymphoma (Raji) using interleukin-2. Cancer. 1997;80:2576–2582. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971215)80:12+<2576::aid-cncr33>3.3.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kassis AI, Sastry KSR, Adelstein SJ. Kinetics of uptake, retention, and radiotoxicity of 125IUdR in mammalian cells: implications of localized energy deposition by Auger processes. Radiat Res. 1987;109:78–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bloomer WD, McLaughlin WH, Weichselbaum RR, et al. Iodine-125-labelled tamoxifen is differentially cytotoxic to cells containing oestrogen receptors. Int J Radiat Biol. 1980;38:197–202. doi: 10.1080/09553008014551101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kassis AI, Fayad F, Kinsey BM, Sastry KSR, Taube RA, Adelstein SJ. Radiotoxicity of 125I in mammalian cells. Radiat Res. 1987;111:305–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walicka MA, Ding Y, Roy AM, Harapanhalli RS, Adelstein SJ, Kassis AI. Cytotoxicity of [125I]iodoHoechst 33342: contribution of scavengeable effects. Int J Radiat Biol. 1999;75:1579–1587. doi: 10.1080/095530099139188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Costantini DL, Chen C, Cai Z, Vallis KA, Reilly RM. 111In-labeled trastuzumab (herceptin) modified with nuclear localization sequences (NLS): an Auger electron-emitting radiotherapeutic agent for HER2/neu-amplified breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1357–1368. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.037937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reske SN, Deisenhofer S, Glatting G, et al. 123I-ITdU–mediated nanoirradiation of DNA efficiently induces cell kill in HL60 leukemia cells and in doxorubicin-, β-, or γ-radiation–resistant cell lines. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1000–1007. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.040337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kassis AI, Kirichian AM, Wang K, Safaie Semnani E, Adelstein SJ. Therapeutic potential of 5-[125I]iodo-2'-deoxyuridine and methotrexate in the treatment of advanced neoplastic meningitis. Int J Radiat Biol. 2004;80:941–946. doi: 10.1080/09553000400017671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mariani G, Di Sacco S, Bonini R, et al. Biochemical modulation by 5-fluorouracil and l-folinic acid of tumor uptake of intra-arterial 5-[123I]iodo-2'-deoxyuridine in patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 1996;35:941–945. doi: 10.3109/02841869609104049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bloomer WD, Adelstein SJ. 5-125I-iododeoxyuridine as prototype for radionuclide therapy with Auger emitters. Nature. 1977;265:620–621. doi: 10.1038/265620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baranowska-Kortylewicz J, Makrigiorgos GM, Van den Abbeele AD, Berman RM, Adelstein SJ, Kassis AI. 5-[123I]iodo-2'-deoxyuridine in the radiotherapy of an early ascites tumor model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:1541–1551. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90331-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]