Abstract

Background and purpose:

Control of food intake is a complex behaviour which involves many interconnected brain structures. The present work assessed if the noradrenergic system in the lateral septum (LS) was involved in the feeding behaviour of rats.

Experimental approach:

In the first protocol, the food intake of rats was measured. Then non-food-deprived animals received either 100 nL of 21 nmol of noradrenaline or vehicle unilaterally in the LS 10 min after local 10 nmol of WB4101, an α1-adrenoceptor antagonist, or vehicle. In the second protocol, different doses of WB4101 (1, 10 or 20 nmol in 100 nL) were microinjected bilaterally into the LS of rats, deprived of food for 18 h and food intake was compared to that of satiated animals.

Key results:

One-sided microinjection of noradrenaline into the LS of normal-fed rats evoked food intake, compared with vehicle-injected control animals, which was significantly reduced by α1-adrenoceptor antagonism. In a further investigation, food intake was significantly higher in food-deprived animals, compared to satiated controls. Pretreatment of the LS with WB4101 reduced food intake in only food-deprived animals in a dose-related manner, suggesting that the LS noradrenergic system was involved in the control of food intake.

Conclusion and implications:

Activation by local microinjection of noradrenaline of α1-adrenoceptors in the LS evoked food intake behaviour in rats. In addition, blockade of the LS α1-adrenoceptors inhibited food intake in food-deprived animals, suggesting that the LS noradrenergic system modulated food intake behaviour and satiation.

Keywords: lateral septal area, food intake, α1-adrenoceptor, feeding behaviour

Introduction

The control of food intake is complex and involves many interconnected brain structures (Cupples, 2002). The lateral hypothalamus (LH) has been considered the main brain area that regulates feeding behaviour (Anand and Brobeck, 1951; Bernardis and Bellinger, 1996). Electrical stimulation of the LH increases feeding behaviour, whereas chemical lesion of the LH has been reported to decrease food intake (Carr and Simon, 1983; Winn et al., 1984). However, other brain areas are also involved in feeding behaviour control, and among them is the lateral septum (LS).

The LS regulates autonomic and behavioral processes in rats (Covian, 1966; Correa and Polon, 1978; Scopinho et al., 2007). Its involvement in feeding behaviour has been suggested by experiments based on electrolytic lesions (Ellen and Powell, 1962; Paxinos, 1975). Rats with septal lesions display hyperactive behaviour and reduced food intake, which is similar to that observed after LH lesions (Oliveira et al., 1990). The LS projects into the LH and receives a large neural input from the hippocampus that is associated with complex cognitive behaviour (Risold and Swanson, 1997). These observations favour the idea that the LS integrates the neural circuitry controlling food intake.

The microinjection of noradrenaline (NA) into hypothalamic nuclei has been reported to evoke food intake by satiated rats, suggesting that the CNS noradrenergic system is involved in the control of feeding behaviour (Grossman, 1962; Leibowitz, 1975; Leibowitz, 1978). The injection of 6-hydroxydopamine into the hypothalamus evoked decreased eating behaviour, suggesting that the endogenous NA system is involved in the control of food intake (Evetts et al., 1971). Moreover, it has been shown that local α1- and α2-adrenoceptors present in the hypothalamus modulate feeding (Wellman et al., 1993).

Noradrenergic neuronal terminals have been identified throughout the LS (Lindvall and Stenevi, 1978; Risold and Swanson, 1997; Antonopoulos et al., 2004), thus providing a neuroanatomical substrate for a septal noradrenergic pathway.

In a previous study, we reported cardiovascular responses after NA microinjection into the LS, which were mediated by α1-adrenoceptor activation (Scopinho et al., 2006). In this study, we also saw increased food-procuring movements after NA microinjection into the LS. This observation corroborates a previous report by Talalaenko (1976) showing increased intensity and number of conditioned food-procuring movements after NA microinjection into the LS.

To clarify the role of the LS noradrenergic system in feeding behaviour control, we studied the effects of NA microinjected into the LS on the eating behaviour of satiated rats. We also studied the possible involvement of α1-adrenoceptors in the effects of NA and examined whether endogenous NA in the LS could be involved in the control of feeding behaviour in food-restricted rats.

Methods

Animal preparation

The institution's animal ethics committee approved the animal housing conditions and experimental procedures. Male Wistar rats (n=88) weighing 230–270 g were used. Animals were kept in the Animal Care Unit of the Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo. Rats were housed individually in plastic cages under standard laboratory conditions, under a 12-h light-dark cycle (lights on from 0600 to 1800 h), with free access to food and water (according to the experiment). All experimental procedures were carried out during the lights-on cycle.

Five days before the experiment, rats were anaesthetized with tribromoethanol (250 mg kg−1 i.p.). After scalp anaesthesia with 2% lidocaine, the skull was exposed and stainless steel guide cannulae (26 G) were stereotaxically implanted unilateral or bilaterally into the LS. Coordinates for cannula implantation into the LS bilaterally were AP=+8.3 mm; L=+2.5 mm from the medial suture and V=−4.4 mm from the skull, with 22° lateral inclination. Coordinates for cannula implantation into the LS unilaterally were AP=+8.3 mm; L=+0.5 mm from the medial suture and V=−4.4 mm from the skull and AP=−1.5 mm (from bregma), L=+1.8 mm from the medial suture and V=−3 mm from the skull for cannula implantation into the lateral ventricle (LV). The use of different coordinates for bilateral or unilateral cannula implantation was necessary to minimize tissue damage, by increasing the distance between cannulae.

After surgery, the animals were treated with a polyantibiotic preparation of streptomycins and penicillins i.m. (Pentabiotico, Fort Dodge, Brazil) to prevent infection and with the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory flunixine meglumine i.m. (Banamine; Schering Plough, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil) for post-operative analgesia.

Drug injection

The drugs were dissolved in artificial CSF with the following composition: 100 mM NaCl; 2 mM Na3PO4; 2.5 mM KCl; 1.0 mM MgCl2; 27 mM NaHCO3; and 2.5 mM CaCl2 (pH=7.4). Needles (33 G, Small Parts, Miami Lakes, FL, USA) that were used for microinjection into the LS were 1 mm longer than guide cannulae and were connected to a 2-μL syringe (7002H; Hamilton, USA) through PE-10 tubing. Drugs were injected in a final volume of 100 nL over 15 s, and the injection needle was left in place for 20 s before being removed. When bilateral injections were made, the needle was removed from the first cannula and inserted into the second one for contralateral microinjection.

Experimental protocol

The first protocol was intended to determine the effect of NA injection into the LS on food intake. On the day of the experiment, rats were placed individually in plastic cages (test cage) inside a soundproof room. The tests were initiated after a 20-min period of adaptation. One group of animals received 21 nmol of NA (Scopinho et al., 2006) or 100 nL vehicle unilaterally into the LS. Another group of animals were microinjected with 10 nmol of the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist 2-(2,6-dimethoxyphenoxyethyl)aminomethyl-1,4-benzodioxane hydrochloride (WB4101) (Scopinho et al., 2006) or vehicle into the LS, 10 min before NA injection. Immediately after these injections, a petri dish with food pellets, previously weighed, was placed in the test cage. The food intake test lasted 1 h, and the petri dish was reweighed to calculate food intake. Food spillage on the cage floor was considered and weighed. No water was available during the trials.

In the second protocol, we tested the role of the local LS noradrenergic system in food intake. One day before the test, the animals were divided into two groups: animals that had access to food (non-deprived) and 18 h food-restricted (deprived) animals (Kittner et al., 2006). On the next day, animals were tested after being submitted to the previously described conditions of adaptation. The two groups of animals were microinjected with 1, 10 or 20 nmol of WB4101 or 100 nL of vehicle bilaterally into the LS, immediately before the food-intake test, which lasted 1 h.

Histological procedure

At the end of the experiments, rats were anaesthetized with urethane (1.25 g kg−1 i.p.), and 100 nL of 1% Evan's blue dye was unilaterally or bilaterally injected into the LS to mark injection sites. The chest was surgically opened, the descending aorta occluded, the right atrium severed and the brain perfused with 10% formalin through the left ventricle. The brain was post-fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h at 4 °C, and 40-μm sections were cut using a cryostat (CM-1900; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Serial brain sections were stained with 1% neutral red and injection sites determined using the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1997). Sections were stained with 0.5% cresyl violet for light microscopy analysis. Placement of injection needles was verified in serial sections.

Statistical analysis

Total food consumption was expressed as the mean±s.e.mean of food intake during the eating test period. In the first experiment, data were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test. In the second experiment, data were analysed using two-way ANOVA with condition (control or food-deprived group) as the independent factor and treatment as the repeated measure. In case of significant interaction, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post-test was performed separately on each condition group. A difference with P<0.05 was considered significant.

Drugs

The following drugs were used: NA-HCl (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), WB4101 (Tocris, Ellisville, MO, USA), urethane (Sigma) and tribromoethanol (Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA).

Results

A diagrammatic representation showing the injection sites of all drugs and photomicrographs showing representative unilateral and bilateral injection sites in the LS are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Left—photomicrographs of a coronal brain section from a representative rat showing the unilateral and bilateral microinjection sites in the lateral septal area (LS). Right—diagrammatic representations based on the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1997) indicating injection sites.

Effect of noradrenaline or vehicle microinjection into the LS on food intake by satiated rats before and after local microinjection of vehicle or the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist WB4101

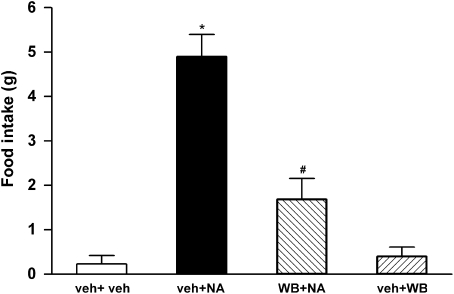

Microinjections of 21 nmol of NA into the LS of satiated rats evoked increased food intake as compared with vehicle control rats (F3,16=34, P<0.001, n=5 each group; Figure 2). Treatment with WB4101 had no effect on food intake when compared with vehicle control rats (P>0.05, n=5). However, this drug reduced the food intake caused by NA treatment (before WB4101=5±0.4 g and after WB4101+NA=1.7±0.5 g, P<0.001 n=5 each group; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of 21 nmol noradrenaline (NA) injected into the lateral septal area after vehicle (veh+NA, n=5) or 10 nmol of WB4101 (WB+NA, n=5) or 10 nmol WB4101 after vehicle (veh+WB, n=5) on food intake (g) compared with control animals (veh+veh, n=5). Columns represent means and bars the s.e.mean, *P<0.01, compared with control group; #P<0.01, compared with NA after vehicle, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-tests.

Microinjection of 21 nmol in 100 nL of NA into the LV had no effect on food intake as compared with vehicle control rats (0.4±0.2 vs 0.5±0.2 g, t=0.19, P>0.05, n=5 each group).

Effect of WB4101 or vehicle injection into the LS on food intake by satiated or food-deprived rats

There were significant effects on condition (F1,40=683, P<0.001), treatment (F3,40=39, P<0.001) and interaction between the two factors (F3,40=42, P<0.001) for total food intake (n=6 each group). Vehicle-treated, food-deprived rats consumed more food than control non-deprived animals (Figure 3). One-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of treatment on food-deprived animals (F3,20=48, P<0.001). Microinjection of WB4101, either 10 or 20 nmol (P<0.001 and P<0.01, respectively), into the LS, but not of 1 nmol WB4101 (P>0.05, n=6 each dose), reduced food intake by food-deprived animals as compared with the respective vehicle-treated group (P<0.01 and P<0.001; Figure 3). Non-linear regression analysis indicated a significant correlation between dose and reduction in food consumption by deprived animals (r2=0.85, d.f.=14, P<0.01). In non-deprived animals, no significant effect of treatment was observed (F3,20=0.7, P>0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of bilateral microinjection of 100 nL of vehicle (n=6 in both groups) or 1, 10 or 20 nmol of WB4101 in 100 nL (n=6 in each groups) on food intake (g) by non-deprived or food-deprived rats. Columns represent the means and bars the s.e.mean, *P<0.001 and #P<0.01 (compared with vehicle-deprived group), Bonferroni's post-test.

Microinjection of 20 nmol of WB4101 into the LV had no effect on food intake by food-deprived animals when compared with vehicle-treated group (6.2±0.5 vs 6.9±0.4 g, t=1.3, P>0.05, n=5 each group).

Discussion

Central catecholaminergic neurotransmission is involved in the control of food intake in many species. I.c.v. injections of catecholamine were reported to increase food intake in pigeons (Canello et al., 1993). In addition, it has been shown that intrahypothalamic injections of adrenoceptor agonists induce eating behaviour in satiated rats (Grossman, 1962; Broekkamp and van Rossum, 1972).

In the present study, we found that NA administration into the LS increases food intake in satiated rats. Rats with septal lesions display hyperactivity and constant interruption of feeding caused by engagement in other activities that are incompatible with eating (Flynn et al., 1986). In addition, electrical stimulation of this region increased food intake (Altman and Wishart, 1971). As part of the limbic system, the LS relays signals related to sensory and reward properties of feeding, and the large hippocampal input to the LS may also be related to learning and memory of feeding (Urban, 1998). Several studies point to an interaction between the LS area and the LH on control of feeding behaviour. Lesions of the LS increase LH-stimulated feeding behaviour, whereas LS stimulation inhibits LH-stimulated feeding (Oliveira et al., 1990). A report showing that electrical stimulation of the LS results in increased c-Fos immunoreactivity in the LH suggests that these two regions are functionally connected (Varoqueaux and Poulain, 1999). The LS may also influence food intake by direct input projections to the LH because the LS sends monosynaptic projections to the LH, a region that has a well-established role in feeding behaviour (Swanson and Cowan, 1979; Bernardis and Bellinger, 1996; Tavares et al., 2005).

Noradrenaline has been reported to increase feeding behaviour after its microinjection into other brain areas, such as the ventromedial hypothalamus and the paraventricular nucleus (Grossman, 1962; Leibowitz, 1975). Furthermore, NA increased food intake when injected into the medial septum and decreased food intake when injected into the LS of the domestic fowl (Denbow and Sheppard, 1993). This decrease in the food intake evoked by NA microinjection into the LS reported by these authors may be due to species differences.

The increased food intake observed after NA microinjection into the LS was significantly reduced by pretreatment with the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist WB4101, suggesting that these receptors in the LS are involved in eating behaviour control. Pretreatment (i.c.v.) with phentolamine, an α-adrenoceptor antagonist, but not with propranolol, a β-adrenoceptor antagonist, abolished food intake induced by i.c.v. injections of NA in pigeons (Ravazio and Paschoalini, 1991). Also, Ritter et al. (1975) reported that NA microinjection into a rat's forebrain nuclei increased food intake, an effect blocked by phentolamine. In other brain areas, such as the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, the activation of α1-adrenoceptors suppressed food intake (Wellman et al., 1993), suggesting that NA plays different roles in food intake behaviour in different brain areas.

Noradrenaline has been related to arousal and control of feeding behaviour. Studies using push-pull cannulae have shown NA release in the paraventricular nucleus during food consumption (Martin and Myers, 1975; Paez et al., 1993). The idea that central catecholaminergic neurotransmission is involved in the control of food intake was suggested earlier by the results of Evetts et al. (1971). These authors reported that local administration of 6-hydroxydopamine into the hypothalamus of non-satiated rats decreased food intake. 6-Hydroxydopamine has been reported to cause selective and irreversible degeneration of catecholamine-containing nerve terminals in the brain (Ungerstedt, 1968).

It has been shown that a dense catecholaminergic innervation exists in the LS, characterized by terminals containing dopamine β-hydroxylase (Lindvall and Stenevi, 1978). This innervation comes from the locus coeruleus. This noradrenergic input is the main source of NA in the LS (Risold and Swanson, 1997; Antonopoulos et al., 2004).

Thus, the present work also considered the role of endogenous NA in the LS in the control of food intake. To investigate this possibility, we injected an α-adrenoceptor antagonist into the LS. The bilateral microinjection of the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist WB4101 into the LS of non-food-deprived rats did not change food intake. However, in food-deprived rats, WB4101 evoked a dose-related reduction in food intake when compared with the control group, which received vehicle injected into the LS. This result suggests that the noradrenergic system in the LS needs to be activated and that endogenous NA, by acting on α1-adrenoceptors, modulates food intake in food-deprived rats. Thus, our data favour the idea of a physiological role for NA in the LS in the control of eating behaviour.

We also observed that microinjection of the same dose and volume of NA into the LV did not increase food intake by satiated rats, suggesting that the effect of NA is due to activation of adrenoceptors in the LS and not in adjacent areas. Ravazio and Paschoalini (1991) reported that NA microinjection into the LV of satiated rats increased food intake. Perhaps this effect was due to the large volume (one microlitre) that was injected into the LV by these authors. Moreover, the microinjection of WB4101 (20 nmol per 100 nL) into the LV also did not affect food intake by food-deprived animals, confirming that the LS is involved in the control of food intake.

Although the hypothalamus should be the main structure involved in the control of food intake, our results show that the LS noradrenergic system also participates in this control. In addition, the release of endogenous NA in this area decreases food intake in food-deprived rats, suggesting that the LS noradrenergic system is important for eating behaviour and food intake. Thus, our results provide evidence that through the hippocampal-septum-hypothalamic complex, the LS is involved in the control of food intake, which supports the hypothesis of a neural circuitry that governs eating through the noradrenergic system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ivanilda AC Fortunato for technical help. The present research was supported by grants from CNPq (505394/2003-0) and FAPESP (2007/04863-2). Dr A Leyva helped with English editing of the paper.

Abbreviations

- LH

lateral hypothalamus

- LS

lateral septum

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Altman JL, Wishart TB. Motivated feeding behavior elicited by electrical stimulation of the septum. Physiol Behav. 1971;6:105–109. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(71)90076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand BK, Brobeck JR. Localization of a ‘feeding center' in the hypothalamus of the rat. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1951;77:323–324. doi: 10.3181/00379727-77-18766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonopoulos J, Latsari M, Dori I, Chiotelli M, Parnavelas JG, Dinopoulos A. Noradrenergic innervation of the developing and mature septal area of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2004;476:80–90. doi: 10.1002/cne.20205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardis LL, Bellinger LL. The lateral hypothalamic area revisited: ingestive behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1996;20:189–287. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekkamp C, van Rossum JM. Clonidine induced intrahypothalamic stimulation of eating in rats. Psychopharmacologia. 1972;25:162–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00423193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canello M, Ravazio MR, Paschoalini MA, Marino-Neto J. Food deprivation- vs intraventricular adrenaline-induced feeding and postprandial behaviors in the pigeon (Columba livia) Physiol Behav. 1993;54:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90327-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr KD, Simon EJ. The role of opioids in feeding and reward elicited by lateral hypothalamic electrical stimulation. Life Sci. 1983;33 Suppl 1:563–566. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90565-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa FM, Polon VL. Effect of electrical stimulation of lateral septal area on blood pressure in anesthetized and unanesthetized rats. Acta Physiol Lat Am. 1978;28:69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covian MR. [Physiology of the septal area] Acta Physiol Lat Am. 1966;16:119–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupples WA. Integrating the regulation of food intake. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R356–R357. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00269.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denbow DM, Sheppard BJ. Food and water intake responses of the domestic fowl to norepinephrine infusion at circumscribed neural sites. Brain Res Bull. 1993;31:121–128. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellen P, Powell EW. Effects of septal lesions on behavior generated by positive reinforcement. Exp Neurol. 1962;6:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(62)90010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evetts KD, Fitzsimons JT, Setler PE. Eating caused by release of endogenous noradrenaline after injection of 6-hydroxydopamine into the diencephalon of the rat. J Physiol. 1971;216:68P–69P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn FW, Evey LA, Steele TL, Mitchell JC. The relation of feeding and activity following septal lesions in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1986;100:416–421. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.100.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SP. Direct adrenergic and cholinergic stimulation of hypothalamic mechanisms. Am J Physiol. 1962;202:872–882. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1962.202.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittner H, Franke H, Harsch JI, El-Ashmawy IM, Seidel B, Krugel U, et al. Enhanced food intake after stimulation of hypothalamic P2Y1 receptors in rats: modulation of feeding behaviour by extracellular nucleotides. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:2049–2056. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz SF. Pattern of drinking and feeding produced by hypothalamic norepinephrine injection in the satiated rat. Physiol Behav. 1975;14:731–742. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(75)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz SF. Paraventricular nucleus: a primary site mediating adrenergic stimulation of feeding and drinking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1978;8:163–175. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(78)90333-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall O, Stenevi U. Dopamine and noradrenaline neurons projecting to the septal area in the rat. Cell Tissue Res. 1978;190:383–407. doi: 10.1007/BF00219554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GE, Myers RD. Evoked release of [14C]norepinephrine from the rat hypothalamus during feeding. Am J Physiol. 1975;229:1547–1555. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.229.6.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira LA, Gentil CG, Covian MR. Role of the septal area in feeding behavior elicited by electrical stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus of the rat. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1990;23:49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paez X, Stanley BG, Leibowitz SF. Microdialysis analysis of norepinephrine levels in the paraventricular nucleus in association with food intake at dark onset. Brain Res. 1993;606:167–170. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91586-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G. The septum: neural systems involved in eating, drinking, irritability, nuricide, copulation, and activity in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1975;89:1154–1168. doi: 10.1037/h0077182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press: Sydney, Australia; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ravazio MR, Paschoalini MA. Participation of alpha receptors in the neural control of food intake in pigeons. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1991;24:943–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risold PY, Swanson LW. Chemoarchitecture of the rat lateral septal nucleus. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;24:91–113. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter S, Wise D, Stein L. Neurochemical regulation of feeding in the rat: facilitation by alpha-noradrenergic, but not dopaminergic, receptor stimulants. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1975;88:778–784. doi: 10.1037/h0076402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scopinho AA, Crestani CC, Alves FH, Resstel LB, Correa FM. The lateral septal area modulates the baroreflex in unanesthetized rats. Auton Neurosci. 2007;137:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scopinho AA, Resstel LB, Antunes-Rodrigues J, Correa FM. Pressor effects of noradrenaline injected into the lateral septal area of unanesthetized rats. Brain Res. 2006;1122:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Cowan WM. The connections of the septal region in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1979;186:621–655. doi: 10.1002/cne.901860408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talalaenko AN. [Neurochemical mechanisms of the septum in food getting conditioned responses in rats] Zh Vyssh Nerv Deiat Im I P Pavlova. 1976;26:358–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares RF, Fernandes KB, Pajolla GP, Nascimento IA, Correa FM. Neural connections between prosencephalic structures involved in vasopressin release. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25:663–672. doi: 10.1007/s10571-005-4006-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerstedt U. 6-Hydroxy-dopamine induced degeneration of central monoamine neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 1968;5:107–110. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(68)90164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban IJ. Effects of vasopressin and related peptides on neurons of the rat lateral septum and ventral hippocampus. Prog Brain Res. 1998;119:285–310. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoqueaux F, Poulain P. Projections of the mediolateral part of the lateral septum to the hypothalamus, revealed by Fos expression and axonal tracing in rats. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1999;199:249–263. doi: 10.1007/s004290050226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman PJ, Davies BT, Morien A, McMahon L. Modulation of feeding by hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus alpha 1- and alpha 2-adrenergic receptors. Life Sci. 1993;53:669–679. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90243-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn P, Tarbuck A, Dunnett SB. Ibotenic acid lesions of the lateral hypothalamus: comparison with the electrolytic lesion syndrome. Neuroscience. 1984;12:225–240. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]