Abstract

Intraocular pressure (IOP) is regulated by the resistance to outflow of the eye's aqueous humor. Elevated resistance raises IOP and can cause glaucoma. Despite the importance of outflow resistance, its site and regulation are unclear. The small size, complex geometry, and relative inaccessibility of the outflow pathway have limited study to whole animal, whole eye, or anterior-segment preparations, or isolated cells. We now report measuring elemental contents of the heterogeneous cell types within the intact human trabecular outflow pathway using electron-probe X-ray microanalysis. Baseline contents of Na+, K+, Cl−, and P and volume (monitored as Na+K contents) were comparable to those of epithelial cells previously studied. Elemental contents and volume were altered by ouabain to block Na+-K+-activated ATPase and by hypotonicity to trigger a regulatory volume decrease (RVD). Previous results with isolated trabecular meshwork (TM) cells had disagreed whether TM cells express an RVD. In the intact tissue, we found that all cells, including TM cells, displayed a regulatory solute release consistent with an RVD. Selective agonists of A1 and A2 adenosine receptors (ARs), which exert opposite effects on IOP, produced similar effects on juxtacanalicular (JCT) cells, previously inaccessible to functional study, but not on Schlemm's canal cells that adjoin the JCT. The results obtained with hypotonicity and AR agonists indicate the potential of this approach to dissect physiological mechanisms in an area that is extremely difficult to study functionally and demonstrate the utility of electron microprobe analysis in studying the cellular physiology of the human trabecular outflow pathway in situ.

Keywords: regulatory volume decrease, adenosine receptor agonists, Schlemm's canal cells, juxtacanalicular cells, trabecular meshwork cells

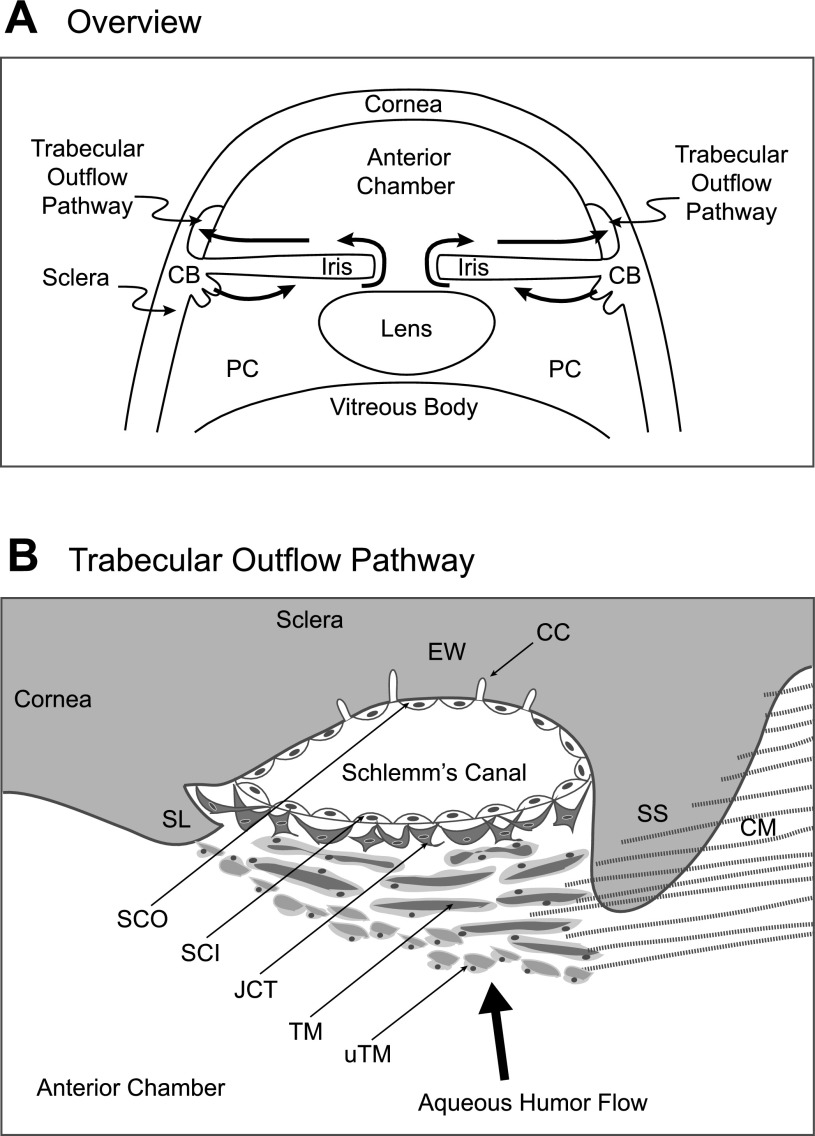

intraocular pressure (IOP) is directly dependent on the rate of aqueous humor secretion (inflow) and the resistance to outflow from the eye. The ciliary epithelium forms the aqueous humor by transporting solute and water from the stroma of the ciliary processes to the posterior chamber of the eye (Fig. 1A). Aqueous humor then flows anteriorly through the pupil into the anterior chamber and exits the eye through pathways near the junction of cornea and sclera (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of trabecular outflow pathway for human aqueous humor at lower (A) and higher (B) resolution. The ciliary epithelium covering the surface of the ciliary body (CB) secretes the aqueous humor into the posterior chamber (PC) and thereafter crosses the pupil to enter the anterior chamber. Fluid exits through the uveal trabecular meshwork (uTM) in series with the corneoscleral trabecular meshwork (TM), juxtacanalicular tissue (JCT), Schlemm's canal inner wall (SCI), Schlemm's canal outer wall (SCO), collector channels (CC), and episcleral veins (not shown). EW identifies the external wall contacting the outer wall of Schlemm's canal. Ciliary muscle (CM) fibers attach to the scleral spur (SS) and to the uTM.

Exit of aqueous humor from the primate eye has long been thought to be primarily through the trabecular outflow pathway (7, 22), consisting of the uveal and corneoscleral trabecular meshwork (TM), juxtacanalicular tissue (JCT), Schlemm's canal (SC), and collector channels (CC) in series (Fig. 1B). The heterogeneous cellular composition, complex structure, and marked species variability among mammals have delayed progress in understanding the cellular physiology.

Fluid flow through the trabecular pathway is pressure dependent. The increase in outflow resistance associated with glaucoma leads to an increase in intraocular pressure (IOP), thereby increasing outflow to match inflow in the new steady state. The increased IOP is a major risk factor in glaucoma, a leading cause of irreversible blindness throughout the world (38). Recent work suggests that a parallel uveoscleral pathway through the ciliary muscle and exiting through the ocular venous system may be more significant than previously thought, particularly in young primates (18, 47). The uveoscleral pathway has been thought to be relatively pressure insensitive and appears highly species dependent.

In vivo, the time course of IOP does not follow the marked circadian rhythm of inflow (3, 27), suggesting that the resistance to outflow through the trabecular pathway is regulated. For example, the resistance to outflow significantly increases during nocturnal hours coincident with the circadian reduction in inflow, serving to partially stabilize IOP (43). The precise sensory and target sites of this regulation are not known but it is likely that regulation occurs somewhere in the anatomical region of the corneoscleral TM, JCT, and inner wall of Schlemm's canal (SCI) (15, 22). The very low absolute magnitude of the outflow resistance has suggested that outflow proceeds between the cells rather than through them (22). However, cells in the outflow pathway must play a role since swelling the cells increases resistance, and shrinking the cells reduces resistance in human, nonhuman primate, and calf eyes (2, 20, 40). Increase in volume of the TM cells has been suggested to increase resistance by restricting the adjacent space through which outflow can proceed (35). Aqueous humor outflow might also be limited by passage through pores within and between the inner-wall cells of Schlemm's canal (15, 21) and through the leaky tight junctions between these cells (39). In addition, changes in cell volume might affect resistance indirectly by releasing extracellular messengers (17) or matrix metalloproteinases (42). These issues have been addressed (22) by structural studies of the intact outflow pathway, with or without cationized ferritin tracer, and by studies of isolated TM or SC cells. However, there have been no studies of potential differential function of the various cell types in the intact outflow pathway. In the present work, we demonstrate the feasibility of measuring the elemental contents within the different cell types by electron probe X-ray microanalysis of the intact tissue, including the first functional analysis of JCT cells. We also report the results of hypotonic challenge, known to increase trabecular outflow resistance, and of exposure to selective A1 and A2A adenosine receptor (AR) agonists, known to exert opposite effects on IOP (4, 6, 12, 13, 46).

METHODS

Preparation of human trabecular outflow tissue.

We isolated trabecular outflow tissue from nonglaucomatous donor eyes stored in moist chambers or from corneoscleral rims stored in solution (Optisol-GS, Bausch and Lomb Surgical, Irvine, CA) at 4°C. Whole eyes were provided by the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI, Philadelphia, PA), and whole eyes and corneoscleral rims were obtained from the Lions Eye Bank of Delaware Valley (Philadelphia, PA) within 96 h after death. A caveat that must be born in mind is that the baseline properties of the tissues studied might not mimic the baseline properties in vivo, because of the postmortem time necessarily involved and because of potentially unidentified premortem disease and medications.

Corneoscleral tissue, either dissected from whole eyes or as corneoscleral rims, were placed endothelial side up and divided into two to three samples. With the use of a sapphire knife, remaining iris tissue was gently removed. The preparation was incised through the sclera just posterior and parallel to the scleral spur. A parallel incision was made anterior to Schlemm's canal at an angle of 45° with the surface, intersecting the posterior incision at the scleral surface. The two to three samples of original corneoscleral tissue, containing corneoscleral TM, JCT, and SC with little uveal TM (uTM), were further divided radially in halves, transferred to Petri dishes, and incubated under control or experimental conditions for 30 min. Under control conditions, the tissues were incubated in isotonic Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (290 mosmol/kgH2O, PBS, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Under experimental conditions, drugs were included in the PBS or PBS was diluted with water to generate 33% (200 mosmol/kgH2O) or 50% hypotonic solutions (152 mosmol/kgH2O). After incubation, excess fluid was adsorbed from the tissues with filter paper. The tissues were quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled propane to prevent redistribution of ions and water and stored in liquid nitrogen until further processing for microanalysis.

Frozen tissue was fractured into blocks under a dissecting microscope (×7). Sections were cut 0.6–0.8 μm thick at −110 to −115°C, freeze-dried at 10−4 Pa (equivalent to 7.5 × 10−7 Torr), and transferred to a JEOL JSM 840 scanning electron microscope equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer for analysis.

Data acquisition and reduction.

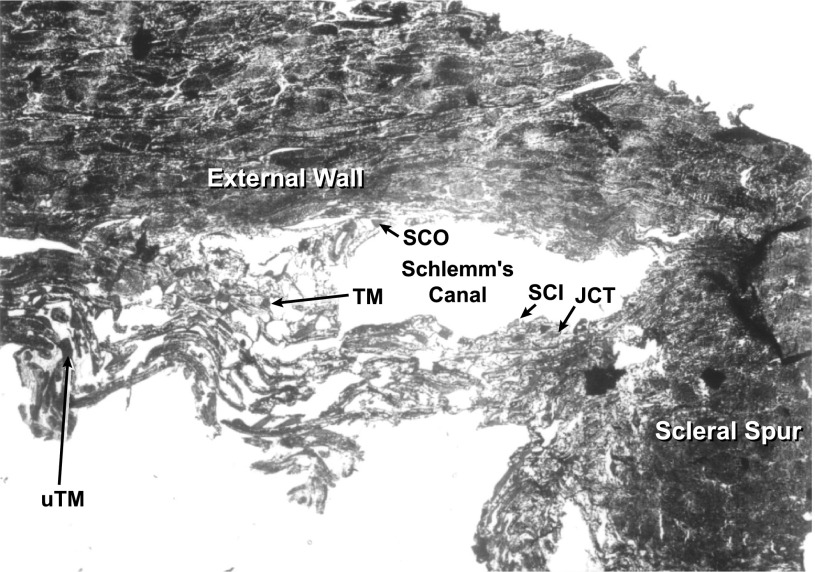

Cell identification was facilitated by reference to SC (Fig. 2). Cells at the luminal surface were identified as outer or inner wall SC cells (SCO and SCI, respectively). Cells just subjacent to the SCI cells were taken to be JCT cells (Fig. 3). Cells more distantly removed were defined as TM cells. Most of the TM cells analyzed were likely of corneoscleral origin. However, a small number of cells may have been uTM in view of their inner position in tissue section (Fig. 3).

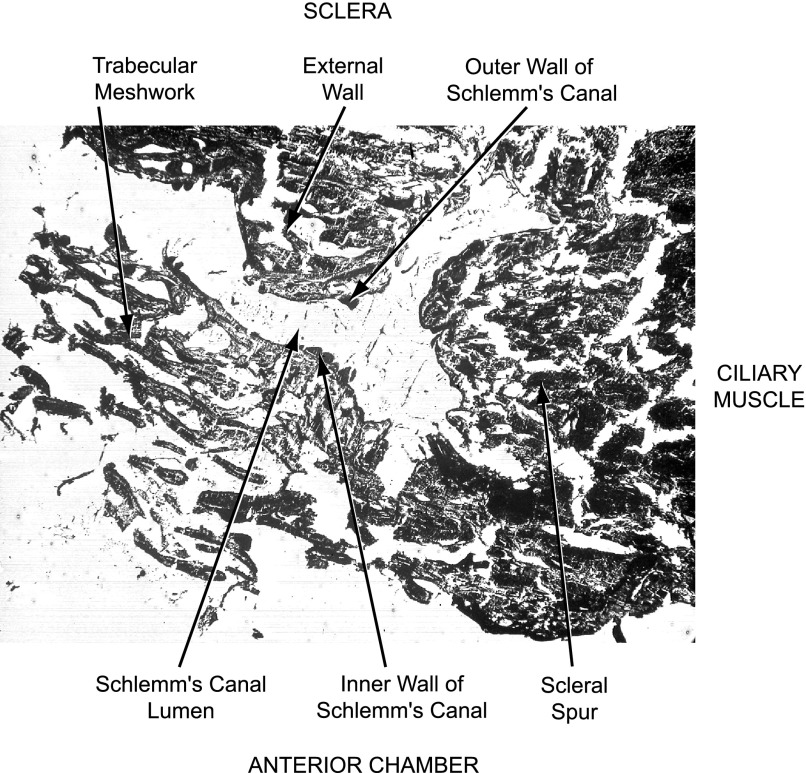

Fig. 2.

Unstained freeze-dried tissue section of human trabecular outflow pathway, illustrating the microscopic anatomy.

Fig. 3.

Representative freeze-dried tissue section illustrating identification of cells included in analyses presented in tables. Arrows identify cells SCI and SCO, the JCT, corneoscleral TM, and uTM.

Intracellular areas within the individual outflow cells were probed with the electron beams. Measurements were performed by scanning the beam over a rectangular area ranging from ∼0.6 × 0.8 μm to ∼1.5 × 2.0 μm, depending on the cell geometry. A probe current of 140–200 pA was applied for 100 s at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. As in past studies (8, 29–33), the area scanned was chosen to preclude contamination with extracellular Na+ and Cl− that might contribute to measurements conducted at intracellular sites closer to the plasma membrane. Thus part or all of the nucleus was included. The incident electrons ionize only a small fraction of the irradiated atoms. When an electron is knocked out of an inner shell, an electron from an outer atomic shell can take its place. Relaxation from a higher to a lower energy state releases an X-ray photon. X-rays were collected and analyzed with a Tracor Northern 30 mm2, energy-dispersive X-ray detector. The element is identified from the X-ray energy while the number of quanta collected at each characteristic energy permits quantification of its content.

As previously described, signals were quantified by filtered least-squares fitting to a library of monoelemental peaks (9). The Na, Mg, Si, P, S, Cl, K, and Ca spectra in that library were obtained from microcrystals sprayed onto a Formvar film. In addition to producing element-characteristic X-rays, electron beam irradiation generates nonquantal white or continuous radiation (Bremsstrahlung), arising from electron deceleration by coulombic interaction with atomic nuclei. These white counts (w), providing an index of tissue mass (10), were obtained over the energy range 4.6–6.0 keV and corrected for contaminant contributions from the Al specimen holder and Ni grid. As noted previously (30), Na, K, and Cl signals were normalized as molar ratios to the P signal determined in the same scanned area. Phosphorus is particularly appropriate for normalization because its intracellular signal is constant, almost entirely reflecting covalently linked atoms (e.g., Ref. 10). The normalization to P has been validated elsewhere by the close linear relationship between the two largely intracellular elements K and P (Fig. 3, Ref. 8).

Water is not directly measured by electron probe X-ray microanalysis. However, the sum of the normalized contents of Na and K [(Na+K)/P] has proved to be a useful index of intracellular water content (1). We have also used the normalized anion gap, defined as (Na+K-Cl)/P, as an approximate index of changes in intracellular HCO3− content (33), although other unmeasured anions can also contribute to this parameter.

Statistics.

Elemental microanalyses of the different cell types under control and experimental conditions are presented as means ± SE in the tables and figures. To ensure robustness of the analyses, means were included only if based on at least 10 microanalyses. Unless otherwise stated, the probability (P) of the null hypothesis was estimated by Student's t-test, defining significance as P < 0.05. One-way ANOVA using the Bonferroni test was used to test for the significance of differences among multiple means.

Drugs.

All drugs were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO).

RESULTS

Identification of cells within trabecular outflow pathway.

Figure 2 provides an orientation of the outflow pathway that can be observed in an unstained and unfixed freeze-dried section. Centered in the electron micrograph is SC. The anterior chamber that had contained aqueous humor corresponds to the bottom of the figure. Above the figure, and not included, would be the external scleral surface (at the top) and the ciliary muscle (to the right). At the left center of the figure, the inner surface of SC appears smooth and lined with cells, indicating that the lumen did not simply arise from fracture during cryosectioning. Cells of the inner and outer walls of the canal, as well as trabecular meshwork cells, are identified with arrows.

Figure 3 presents a tissue section illustrating cells identified as: inner wall (SCI) and outer wall (SCO) cells from SC, a JCT cell, a corneoscleral TM cell, and an uTM cell. The loop of tissue displaced downward just to the left of the scleral spur at the bottom of the figure was also likely of uTM origin. However, as illustrated here, the uTM was often fractured so that identifying uTM was less certain than recognizing SCI and SCO cells, JCT cells, and corneoscleral TM cells.

Intracellular elemental contents under baseline and ouabain-treated conditions.

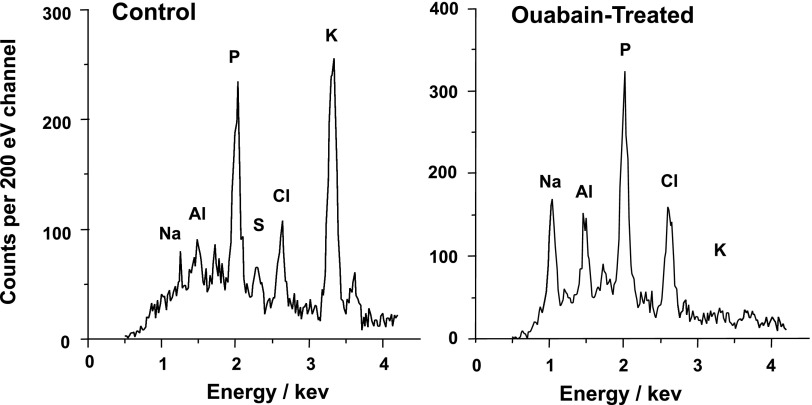

Table 1 presents the elemental contents of all cells analyzed in the trabecular outflow pathway under control conditions. The high K+ and P contents and low Na+ and Cl− contents documented that the areas analyzed were indeed intracellular. The phosphorus content (normalized to white counts), Na/P, Cl/P, K/P, cell volume [monitored as (Na+K)/P], and unmeasured anion contents [(Na+K-Cl)/P] were comparable to the contents of ciliary epithelial cells we have recently analyzed (32). Incubation with 100 μM ouabain for 30 min to block the Na+-K+-activated ATPase increased the mean Na/P and decreased K/P by an order of magnitude (N = 122) (Table 1, Fig. 4). The two cell types studied most completely after ouabain incubation, and included in Table 1, were the TM cells (N = 74) and the SCI cells (N = 20). Ouabain increased Na/P to 1.730 ± 0.055 and reduced K/P to 0.111 ± 0.015 in TM cells and raised Na/P to 1.506 ± 0.095 and reduced K/P to 0.104 ± 0.019 in the SC cells. These ouabain-produced changes did not simply reflect an exchange of intracellular K+ for extracellular Na+. With loss of cell K+, the membrane is expected to depolarize. The depolarization should permit influx of Cl−, counterbalanced by Na+, thus producing the observed increases in Cl/P and volume, followed as (Na+K)/P (Table 1).

Table 1.

Elemental contents of outflow cells under baseline conditions and following ouabain exposure

| All Cells | Condition | n | Na/P | Cl/P | K/P | P/w | (Na + K)/P | (Na + K−Cl)/P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outflow | Control | 985 | 0.142±0.003 | 0.341±0.004 | 1.075±0.006 | 846±6 | 1.217±0.007 | 0.877±0.005 |

| Outflow | Ouabain | 122 | 1.647±0.041 | 0.707±0.030 | 0.113±0.011 | 676±18 | 1.760±0.038 | 1.053±0.021 |

| Inflow | Control | 772 | 0.084±0.003 | 0.262±0.003 | 1.198±0.006 | 862±5 | 1.282±0.006 | 1.020±0.005 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of cells analyzed. Na, Cl, K, (Na + K), and (Na + K−Cl) contents are expressed as mmol/mmol P. P/w is the phosphorus content normalized to tissue mass by dividing the P counts by the white radiation counts (w) measured over the the energy range 4.6–6.0 keV (see methods). The entries include all cell types of the trabecular outflow pathway, under baseline conditions, and after incubation with 100 μM ouabain for 30 min. Included for comparison are previously published baseline elemental contents of nonpigmented and pigmented ciliary epithelial cells from anterior and posterior regions of rabbit ciliary epithelium (32).

Fig. 4.

Representative electron probe X-ray microanalytic spectra under control (A) and ouabain-exposed (B) conditions.

Table 2 presents the elemental contents of all cells measured under control conditions. Included are the SCI and SCO cells, JCT cells, corneoscleral TM cells, and a small set of cells thought to be uTM cells. As noted above, identification of uTM cells was often complicated by fracturing of the uTM. Entries are also present for cells found in the scleral spur (SS) and in the external wall (EW) in contact with the SCO. The SS cells are not expected to be involved in resistance regulation and might reasonably serve as a form of negative control. It might be expected that the EW cells could serve the same purpose. However, the EW just outside SC contains both 30–35 collector channels (19) and cells staining for smooth muscle myosin (14). The heterogeneous cell population of the external wall is not yet well-defined, either anatomically or functionally.

Table 2.

Baseline elemental contents of different cell types in the trabecular outflow pathway

| Cells | Conditions | n | Na/P | Cl/P | K/P | P/w | (Na + K)/P | (Na + K−Cl)/P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCI | Control | 96 | 0.164±0.008 | 0.331±0.012 | 1.020±0.015 | 912±18 | 1.183±0.019 | 0.853±0.014 |

| SCO | Control | 52 | 0.178±0.010 | 0.333±0.014 | 1.055±0.023 | 903±26 | 1.233±0.025 | 0.900±0.018 |

| JCT | Control | 138 | 0.143±0.006 | 0.330±0.009 | 1.047±0.017 | 884±15 | 1.190±0.018 | 0.861±0.013 |

| TM | Control | 545 | 0.131±0.005 | 0.348±0.005 | 1.099±0.009 | 828±17 | 1.229±0.009 | 0.881±0.007 |

| uTM | Control | 21 | 0.137±0.020 | 0.434±0.035 | 1.178±0.058 | 776±35 | 1.315±0.056 | 0.881±0.036 |

| EW | Control | 105 | 0.157±0.008 | 0.313±0.009 | 1.045±0.021 | 807±19 | 1.202±0.022 | 0.889±0.015 |

| SS | Control | 12 | 0.128±0.020 | 0.368±0.018 | 1.136±0.043 | 853±48 | 1.264±0.057 | 0.896±0.051 |

| Total | Control | 985 | 0.141±0.003 | 0.341±0.004 | 1.075±0.006 | 846±6 | 1.217±0.007 | 0.877±0.005 |

Values are means ± SE (expressed as mmol/mmol P); n, number of cells analyzed. Baseline microanalyses of inner (SCI) and outerwall (SCO) Schlemm's canal cells, juxtacanalicular tissue (JCT) cells, corneoscleral trabecular meshwork (TM) cells, and cells identified specifically as uveal trabecular meshwork cell (uTM). Microanalyses from external wall (EW) and scleral spur (SS) cells are also included.

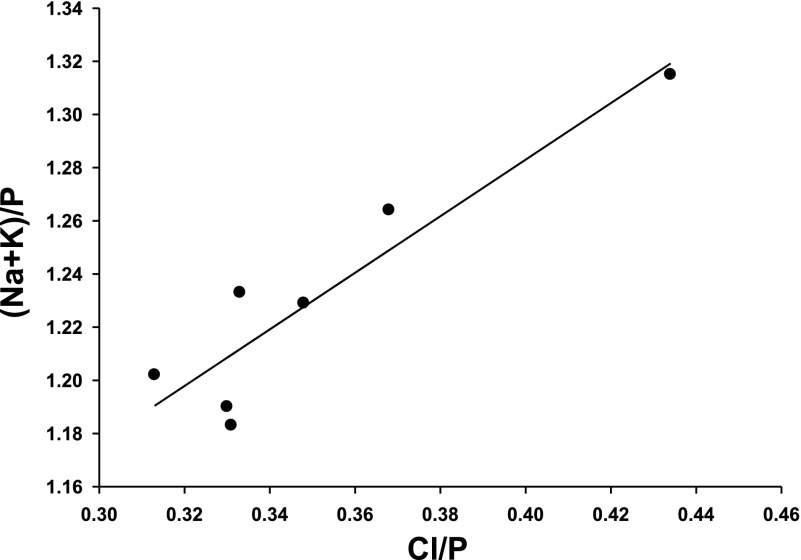

The elemental contents are relatively similar for all cells, but small variations were noted among the various cell types. Since cell volume is expected to be directly dependent on the Cl− content, the cell volume [(Na+K)/P] of the different cell types was predicted to be dependent on the Cl/P of those cells. Figure 5 was generated from the entries of Table 2 and demonstrates that (Na+K)/P is indeed linearly related to Cl/P in the various cell types, with a slope of 1.1 ± 0.2 (P = 0.003, R = 0.925). This linearity did not simply reflect variable contributions of contaminating signals from external NaCl since (Na+K)/P was entirely independent of Na/P (R = 0.0000). The correlation demonstrated in Fig. 5 provides further support that (Na+K)/P is a valid index of cell volume.

Fig. 5.

Relationship between cell volume, monitored as (Na+K)/P, and normalized chloride content (Cl/P) for the different cell types of the outflow pathway. Data points are taken from Table 2. The slope of the linear least-squares fit is 1.1 ± 0.2 (P = 0.003, R = 0.925).

Effects of hypotonic challenge on intracellular elemental contents.

Hypotonic incubation of isolated human TM cells has been previously noted to trigger a regulatory volume decrease (RVD) that could be inhibited by blocking K+ or Cl− channels (34).

As noted in the methods, we do not measure volume directly, but follow changes in cell volume with the sum of the normalized elemental Na and K contents [(Na+K)/P]. When we reduce the external osmolality, water enters the cells. We cannot detect this initial anisosmotic cell swelling with our index of cell volume. Initially, the elemental contents will be unchanged, even when the cell is swollen. What we do detect is the regulatory response to this cell swelling, the release of solute, largely K+ and Cl−.

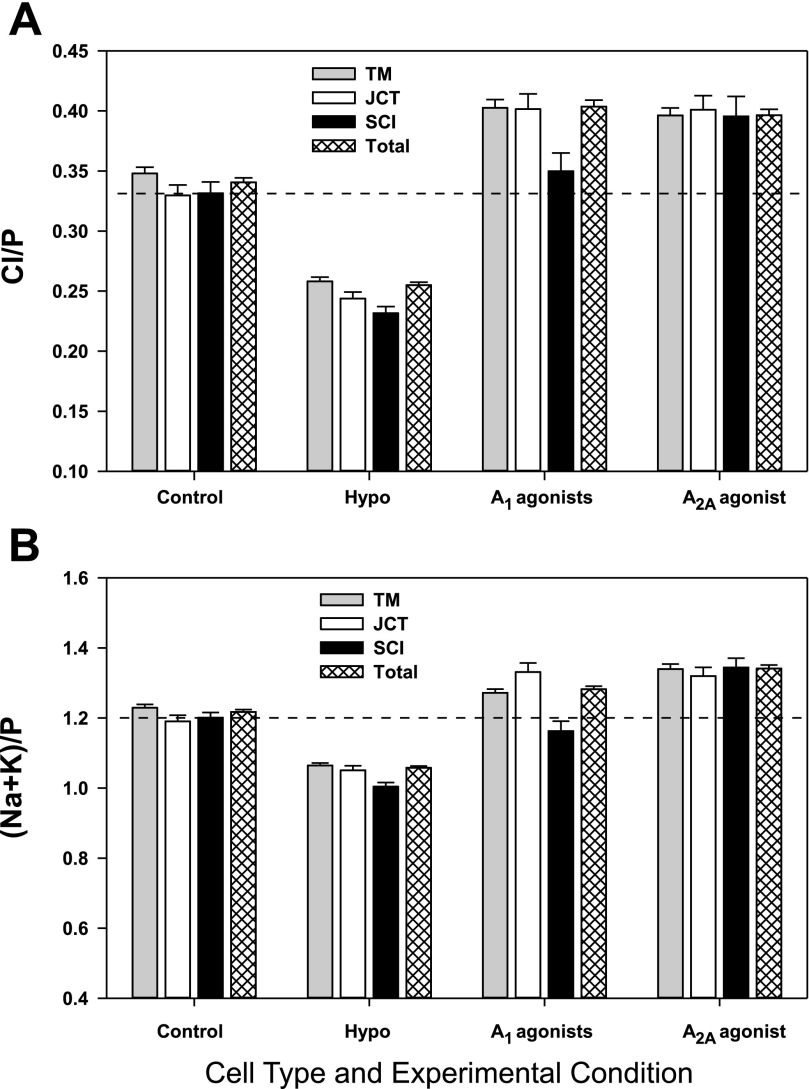

Figure 6, A and B, illustrates the reductions in total Cl− content and volume, respectively, produced by incubating the intact trabecular outflow pathway in hypotonic solution for 30 min. Table 3 presents the corresponding changes in normalized elemental contents and volume based on microprobe analysis of 985 cells under isosmotic and 1,096 cells under hypotonic conditions. From analysis of the total set of cells, the anisosmotic swelling triggered a significant decrease (P < 0.001) from baseline values (Table 2) of Na+, Cl−, K+, and unmeasured anion contents, together with a decrease in cell volume, monitored as (Na+K)/P. Based on Tables 2 and 3, the mean fall in volume of all the cells was 13.1 ± 0.7% (P < 0.011), largely reflecting K+ release. Half the accompanying anion release reflected Cl−, reducing intracellular Cl− by ∼25%, and half by unmeasured anion [(Na+K-Cl)/P], likely reflecting reduced intracellular HCO3−.

Fig. 6.

Bar graphs of normalized Cl− content (A) and normalized cell volume (B), monitored as (Na+K)/P, as functions of cell type and experimental condition. The interrupted horizontal lines present the Cl− contents (A) and volume (B) of SCI cells under control conditions. Cells subjected to hypotonic challenge (Hypo) were incubated in solutions with osmolalities of either 200 or 152 mosmol/kgH2O. The osmolality of the other incubation solutions was 290 mosmol/kgH2O.

Table 3.

Changes in elemental contents of outflow cells following hypotonic challenge

| Cells | n | Na/P | Cl/P | K/P | (Na + K)/P | (Na + K−Cl)/P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCI | 110 | −0.020±0.012 | −0.101±0.014 | −0.163±0.020 | −0.182±0.024 | −0.083±0.018 |

| P (DF = 204) | >0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| SCO | 54 | −0.033±0.016 | −0.099±0.017 | −0.189±0.029 | −0.223±0.032 | −0.124±0.024 |

| P (DF = 104) | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| JCT | 160 | −0.009±0.010 | −0.086±0.010 | −0.131±0.021 | −0.139±0.022 | −0.054±0.017 |

| P (DF = 296) | >0.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.002 | |

| TM | 548 | −0.017±0.006 | −0.090±0.006 | −0.149±0.011 | −0.165±0.011 | −0.075±0.009 |

| P (DF = 1,091) | <0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| uTM | 85 | −0.014±0.022 | −0.128±0.037 | −0.139±0.060 | −0.154±0.059 | −0.025±0.039 |

| P (DF = 104) | >0.5 | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.02 | >0.5 | |

| EW | 92 | −0.039±0.012 | −0.063±0.012 | −0.113±0.025 | −0.153±0.027 | −0.089±0.021 |

| P (DF = 195) | <0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Total | 1,096 | −0.017±0.004 | −0.086±0.004 | −0.141±0.008 | −0.159±0.008 | −0.074±0.006 |

| P (DF = 2,079) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Values are means ± SE (in mmol/mmol P); n, number of cells analyzed. Changes are calculated as elemental contents after hypotonic minus those after isotonic incubation (Table 2). P has been estimated by the t-test, using the indicated degrees of freedom (DF). The hypotonically treated cells were incubated with solutions containing either 200 or 152 mosmol/kgH2O, instead of the 290 mosmol/kgH2O characterizing the isotonic incubation solutions. The results with the two hypotonic solutions were similar and pooled for analysis.

Hypotonicity-triggered solute loss of comparable magnitude was displayed by all cell types. The magnitude of the regulatory reduction in volume {measured as [(Na+K)/P]} can be estimated from the quotient of the absolute change (Table 3) and the baseline absolute value (Table 2). This regulatory loss of intracellular cations was 12–13% for the JCT (P < 0.001), TM (P < 0.001), uTM (P < 0.02), and SL cells (P < 0.001); 15 ± 2% for the SCI cells (P < 0.011); and 18 ± 3% for the SCO cells (P < 0.011). Analyzed by one-way ANOVA, the magnitudes of the regulatory solute loss were not significantly different from one another.

Effects of purinergic agonists on intracellular elemental contents.

The results presented in the figures and tables have been based on more than 3,000 microanalyses of individual cells, and 570 cells were analyzed in studying the effects of two A1 agonists. Nevertheless, the cells lining the surface of SC contribute a relatively small fraction of the total population of cells in the trabecular outflow pathway. Thus the number of SCI cells available for microanalysis proved to be limited. The results of incubating tissues with two selective A1 AR agonists were similar. To enhance the robustness of the calculation, the microanalyses conducted following exposure to the A1 agonists adenosine amine congener (ADAC, N = 14 SCI cells) and (2S)-N6-[2-endo-norbornyl]adenosine (S-ENBA, N = 17 SCI cells) were combined (N = 31 SCI cells) in Table 4 and Fig. 6. A comparable number of SCI cells (N = 36) were analyzed in studying the effects of the single selective agonist (CGS-21680) used to activate A2A ARs (Table 4, Fig. 6).

Table 4.

Changes in elemental contents

| Cells | n | Na/P | Cl/P | K/P | (Na + K)/P | (Na + K−Cl)/P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Produced by A1 agonists | ||||||

| SCI | 31 | −0.031±0.014 | +0.008±0.019 | +0.001±0.027 | −0.030±0.035 | −0.037±0.027 |

| P (DF = 125) | <0.05 | >0.6 | >0.9 | >0.3 | >0.1 | |

| JCT | 72 | +0.003±0.013 | +0.0719±0.015 | +0.138±0.029 | +0.141±0.031 | +0.069±0.026 |

| P (DF = 208) | >0.8 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | |

| TM | 358 | −0.014±0.006 | +0.055±0.009 | +0.056±0.014 | +0.043±0.014 | −0.012±0.012 |

| P (DF = 901) | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.005 | >0.3 | |

| uTM | 39 | −0.021±0.024 | −0.020±0.042 | +0.029±0.067 | +0.009±0.067 | +0.028±0.048 |

| P (DF = 58) | >0.3 | >0.6 | >0.6 | >0.8 | >0.4 | |

| EW | 52 | +0.014±0.017 | +0.097±0.018 | +0.111±0.032 | +0.125±0.036 | +0.027±0.026 |

| P (DF = 153) | >0.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | >0.3 | |

| Total | 570 | −0.016±0.005 | +0.063±0.006 | +0.080±0.010 | +0.065±0.011 | +0.001±0.009 |

| P (DF = 1,553) | <0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | >0.8 | |

| Produced by A2 agonists | ||||||

| SCI | 36 | +0.015±0.016 | +0.058±0.022 | +0.131±0.031 | +0.148±0.035 | +0.089±0.030 |

| P (DF = 130) | >0.3 | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.005 | |

| JCT | 84 | +0.027±0.012 | +0.070±0.015 | +0.103±0.028 | +0.130±0.031 | +0.058±0.023 |

| P (DF = 220) | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.02 | |

| TM | 203 | +0.034±0.008 | +0.048±0.008 | +0.076±0.016 | +0.111±0.017 | +0.062±0.014 |

| P (DF = 746) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| uTM | 56 | +0.034±0.008 | −0.040±0.038 | +0.014±0.063 | +0.048±0.063 | +0.088±0.041 |

| P (DF = 75) | <0.001 | >0.2 | >0.8 | >0.4 | <0.05 | |

| EW | 18 | +0.036±0.024 | +0.086±0.028 | +0.158±0.056 | +0.194±0.064 | +0.108±0.050 |

| P (DF = 121) | >0.1 | <0.005 | <0.01 | <0.005 | <0.05 | |

| Total | 407 | +0.029±0.005 | +0.055±0.006 | +0.096±0.011 | +0.124±0.012 | +0.068±0.009 |

| P (DF = 1,390) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Values are means SE (in mmol/mmol P); n, number of cells analyzed. P has been estimated by the t-test, using the indicated DF.

The only cell type that did not respond to either the A1-or A2A-selective agonists was the uTM cell (Table 4). These cells were not easily distinguished from corneoscleral TM cells within the trabecular outflow pathway, so that the analyses might have included some corneoscleral TM cells, as well. However, most of the large number of TM cells analyzed were likely to have been of corneoscleral origin, and these cells displayed highly significant increases in Cl− and K+ contents and in cell volume following incubation with either A1 or A2A agonists (Table 4, Fig. 6). The JCT cells also gained Cl−, K+, and volume in response to activation of A1 or A2A adenosine receptors.

The SCI responded uniquely to the purinergic agonists. Like the JCT, TM, and SL, the SCI cells gained Cl−, K+, and volume following incubation with the A2A agonist (Table 4, Fig. 6). In contrast, however, the A1 agonists did not significantly alter the Cl− and K+ contents and volume of the SCI cells (Table 4, Fig. 6).

ANOVA of Cl− content and volume for each cell type under control and experimental conditions.

Figure 6, A and B, summarizes the mean Cl− contents and volume, respectively, for TM, JCT, and SCI cells, and for the total set of outflow cells analyzed under control and experimental conditions. The cellular responses to the experimental conditions fell into three patterns.

The first pattern was displayed by JCT, TM, and EW cells. One-way ANOVA of the microanalyses indicated that hypotonicity, A1 agonists and the A2A agonist all significantly changed (P < 0.05) both cell Cl− contents and cell volume. The magnitudes of the increases in Cl/P and volume of the JCT and EW cells were not significantly different after incubation with A1 (Table 4) and A2A agonists (Table 4), but the A2A agonist produced a significantly larger increase in volume than in Cl− contents of the TM cells (Table 4). The second pattern was displayed by SCI cells, whose Cl− contents or volume were not significantly altered by A1 agonists, but were significantly altered by either A2A or hypotonicity. A third pattern was identified by one-way ANOVA of the uTM cells, whose Cl− contents and cell volume were significantly changed by hypotonicity, but not by the A1 or A2A agonists (Table 4).

Of particular interest, the adjoining cell layers of SCI and JCT cells responded differently to agonists of A1 and A2A receptors. The A1 agonists significantly increased the Cl− contents and cell volumes of the JCT cells but not of the SCI cells (Table 4). In contrast, the A2A agonist increased the Cl− contents and cell volumes of both cell types (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

The salient results of the current study were that: 1) the elemental contents of cells within the intact human trabecular outflow pathway for aqueous humor could be monitored by electron probe X-ray microanalysis; 2) anisosmotic swelling triggered a regulatory (Na + K) release of comparable magnitude in all of the cell types in the intact outflow pathway; and 3) differential responses of the several cell types could be identified and quantified by microprobe analysis following incubation with selective adenosine-receptor agonists.

Feasibility of electron probe X-ray microanalysis of the trabecular outflow pathway.

The small size, complexity, and cellular heterogeneity of the trabecular outflow tract have hindered progress in studying the cell physiology of the intact tissue. The present results demonstrate the feasibility of identifying the component cell types even in unfixed, unstained sections of the outflow pathway (Figs. 2 and 3). Microprobe analysis of the component cells revealed high baseline elemental P and K+ contents and low Na+ and Cl− contents, characteristic of intracellular sites under baseline conditions (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, blocking Na+-K+-activated ATPase with ouabain produced the large changes in Na+ and K+ contents characteristically displayed by other cells (Table 1, Fig. 4). These results document the feasibility of functionally studying cells in the human trabecular outflow pathway with electron probe X-ray microanalysis.

RVD of cells in the intact trabecular outflow pathway.

Anisosmotic swelling of isolated human TM cells has previously been found to initiate a RVD that could be inhibited by blocking K+ or Cl− channels (34). Hypotonicity has also been reported to activate K+ and Cl− channels of primary cultures of bovine TM cells (44). Srinivas et al. (45) found swelling-activated Cl− channels in bovine TM cells but, in contrast to Soto et al. (44), did not observe swelling-activated K+ channels or an RVD. Among other possibilities, this might have reflected different origins of the bovine TM cells used. Isolated, cultured bovine and human TM cells express functional heterogeneity (11, 48), and histochemical staining of human TM cells reveals heterogeneous expression of myosin (14).

As noted in the methods and results, we do not measure volume directly but follow changes in cell volume with the measured sum of the normalized elemental Na and K contents [(Na+K)/P]. This index does not detect the initial cell swelling necessarily produced by hypotonic challenge because the total ion content will not change acutely with swelling but does permit us to monitor changes in volume as ions and hence water are released from the cell. The present results demonstrate that hypotonic challenge of the intact human trabecular outflow tissue produces a secondary loss of Cl− content and cell volume, monitored indirectly as (Na+ + K+)/P, by all cell types. By definition, this swelling-activated loss of cell volume conforms to a regulatory volume decrease (26). The magnitudes of the regulatory solute release expressed by the different cell types did not differ significantly from one another (P > 0.3, one-way ANOVA). The mean percentage loss in cell volume displayed by all cells analyzed after hypotonic incubation (N = 1,096) was 13.1 ± 0.7%.

We have previously quantified the RVD of isolated human TM cells by direct volumetric measurements (34). The ∼24% hypotonicity applied to the isolated TM cells of the previous study would be expected to swell perfect osmometers by 31%. The swelling observed was 29 ± 3% (means ± SE, N = 3), very close to the predicted value. Thereafter, both adherent TM cells (studied by fluorometry) and TM cells in suspension (studied by electronic cell sizing) displayed an RVD, a progressive shrinkage in the sustained presence of the hypotonic solution. Adherent cells displayed a regulatory shrinkage of ∼8.3% after 25 min of hypotonic challenge. The TM cells in suspension displayed shrinkages of ∼13% after 30 min and ∼19% after 60 min.

The 33% and 50% hypotonicity applied in the present study would swell perfect osmometers by 45% and 91%, respectively. Based on the data of Tables 2 and 3 in the present study, the 30-min hypotonic incubation was associated with a mean fall in normalized (Na + K) content of all outflow cells of 13.1 ± 0.7%. The surprisingly good quantitative agreement with the previous measurements may well be fortuitous, given the differences in technique, tissue preparation, hypotonic challenge, and other experimental conditions. However, the magnitude of the hypotonically triggered solute release was clearly comparable to the RVD directly measured in isolated cells.

Effects of A1 and A2A AR agonists on the different cell types of the intact outflow pathway.

In general, selective A1 and A2A AR agonists produced similar changes in the Na+, K+, and Cl+ contents and volumes of all cell types (Table 4). The changes in Cl− contents (Fig. 6A) and cell volume (Fig. 6B) were of particular interest in view of the suggestion that changes in cell volume might mediate regulation of fluid flow through the trabecular outflow pathway (35). Consistent with this possibility, the Na+/H+ antiport inhibitor dimethylamiloride both shrinks isolated human TM cells (34) and reduces intraocular pressure (5). As expected, cell volume directly correlated with Cl− content under control conditions (Fig. 5).

Averaging the microanalyses of all outflow cells, the mean increases in Cl− contents (±SE) produced by A1 and A2A agonists were 18 ± 2% and 16 ± 2%, respectively. The corresponding increases in volume were 5 ± 1% and 10 ± 1%, respectively. The larger increase in volume triggered by the A2A agonist reflected an increase in unmeasured anion, presumably bicarbonate, in addition to the Cl− uptake (Table 4). These purinergic effects on the total set of cells were shared by the JCT, TM, and EW cells (Table 4). However, two cell types responded differently. First, the uTM cells responded neither to A1 nor A2A agonists, consistent with prior reports that the TM cells are functionally (11, 48) and immunohistochemically (14) heterogeneous. Second, the A2A agonist did significantly increase the Cl− content and cell volume of the SCI cells, but the A1 agonists affected neither parameter. These results may be relevant to the observation that activation of A1 and A2A ARs exert opposite effects on intraocular pressure (4, 6, 12, 13, 46).

Activation of A1 ARs lowers, and of A2A ARs increases, intraocular pressure in rabbits (12, 13), mice (4, 6), and monkeys (46). At least in monkeys, the A1-mediated reduction in IOP arises entirely from lowered resistance to outflow of aqueous humor (46). The A2A-mediated increase in IOP likely reflects an opposite effect on outflow resistance, since it is ascribable to neither increased inflow of aqueous humor (46) nor to interruption of the blood-aqueous barrier at low agonist doses (12, 13). If changes in cell volume mediate AR-activated changes in outflow resistance, we might predict that A1 agonists would shrink the target cells and A2A agonists should swell them.

The only cell type that responded differentially to A1 and A2A agonists was the SCI cell. A2A caused cell swelling and A1 agonists tended to cause cell shrinkage but not significantly so (Table 4). In part, this is consonant with our electrophysiological findings that A1 agonists increase and A2A agonists decrease, largely K+ currents in pure populations of cultured SCI cells (25). Activation of K+ channels should hyperpolarize the SCI membranes, favoring release of intracellular Cl− and shrink the cells, while depolarization is expected to reduce expulsion of Cl− and swell the cells. This suggests that SCI cell volume may play a role in regulating outflow resistance, but the regulation is likely to involve one or more additional factors. The underlying mechanisms are unclear, but the interaction of SCI and JCT cells may be particularly important.

The JCT has long been known to tether SCI cells in place through cytoplasmic connections (24), thereby preventing the SCI from ballooning into the lumen and obstructing aqueous humor outflow. Tethering is also supported by matrix-matrix interaction between the JCT and basement membrane of the SCI cells (19). However, the close proximity of the two cell types permits the JCT to modify SCI function, beyond simply tethering the SCI in place. Experimental maneuvers that physically separate the JCT from the SCI cells do lead to ballooning of the SCI and can permit the inner SC wall to contact the outer wall. Nevertheless, even in the presence of luminal obstruction in some local regions (28), separation of JCT and SCI reduces the resistance to aqueous humor outflow (28, 36, 41). The effect of separating JCT from SCI has been interpreted in terms of the funneling hypothesis that relates outflow resistance largely to hydrodynamic constraints on aqueous flow through the JCT to exit through pores between and through the SCI cells (23). Separation of JCT from SCI may relieve these constraints, reducing outflow resistance. However, quantitative agreement with the funneling hypothesis has been incomplete (16). An alternative possibility is that the JCT cells function analogously to pericytes regulating flow through capillaries (e.g., Ref. 37). Here, swelling of JCT and SCI cells follows A2A AR stimulation (which is associated with increased outflow resistance), and swelling of JCT but not SCI cells follows A2A AR stimulation (which is associated with reduced outflow resistance). Changes in the relative cell volumes of these adjoining cell types might possibly lead to changes in mechanical coupling and SCI cell pore formation.

Contribution of electron probe X-ray microanalysis.

The present results indicate that cells in the intact trabecular outflow pathway likely function differently from those cells studied in isolation. First, reports of isolated cells have not agreed whether swelling of TM cells activates K+ channels and an RVD. In the intact tissue, we have now found that all cells of the outflow pathway, including the TM, express an RVD. Second, in contrast to previous studies of isolated human TM cells derived from mixed populations (34) or from a single cloned line (25), we have found that selective A1 and A2A agonists increase cell volume of TM cells in the intact tissue. In addition, electron probe X-ray microanalysis has permitted the first functional study of JCT cells in the intact outflow pathway, revealing that they respond to AR agonists differently from the adjoining layer of SCI cells. The microprobe has thus provided an unusual opportunity to begin studying the cell physiology of the trabecular outflow path.

GRANTS

This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Research Grant EY-013624 (to M. M. Civan) and Core Grant EY-01583, by Pro Retina Germany and a Fellowship from the Herbert Funke Foundation, Germany (to M. O. Karl), the Paul and Evanina Bell Mackall Foundation Trust (to R. A. Stone) and Research to Prevent Blindness (to R. A. Stone).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Lions Eye Bank of Delaware Valley (Philadelphia, PA), its Technical Director, Robert Lytle, and the entire staff, as well as the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI, Philadelphia, PA), in providing the postmortem samples.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham EH, Breslow JL, Epstein J, Chang-Sing P, Lechene C. Preparation of individual human diploid fibroblasts and study of ion transport. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 248: C154–C164, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Aswad LA, Gong H, Lee D, O'Donnell ME, Brandt JD, Ryan WJ, Schroeder A, Erickson KA. Effects of Na-K-2Cl cotransport regulators on outflow facility in calf and human eyes in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 40: 1695–1701, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asejczyk-Widlicka M, Pierscionek BK. Fluctuations in intraocular pressure and the potential effect on aberrations of the eye. Br J Ophthalmol 91: 1054–1058, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avila MY, Carré DA, Stone RA, Civan MM. Reliable measurement of mouse intraocular pressure by a servo-null micropipette system. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42: 1841–1846, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avila MY, Seidler RW, Stone RA, Civan MM. Inhibitors of NHE-1 Na+/H+ exchange reduce mouse intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43: 1897–1902, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avila MY, Stone RA, Civan MM. A(1)-, A(2A)- and A(3)-subtype adenosine receptors modulate intraocular pressure in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol 134: 241–245, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bill A, Phillips CI. Uveoscleral drainage of aqueous humour in human eyes. Exp Eye Res 12: 275–281, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowler JM, Peart D, Purves RD, Carré DA, Macknight AD, Civan MM. Electron probe X-ray microanalysis of rabbit ciliary epithelium. Exp Eye Res 62: 131–139, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowler JM, Purves RD, Macknight AD. Effects of potassium-free media and ouabain on epithelial cell composition in toad urinary bladder studied with X-ray microanalysis. J Membr Biol 123: 115–132, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Civan MM Epithelial Ions & Transport: Application of Biophysical Techniques. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1983, p. 1–204.

- 11.Coroneo MT, Korbmacher C, Flugel C, Stiemer B, Lütjen-Drecoll E, Wiederholt M. Electrical and morphological evidence for heterogeneous populations of cultured bovine trabecular meshwork cells. Exp Eye Res 52: 375–388, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crosson CE Adenosine receptor activation modulates intraocular pressure in rabbits. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 273: 320–326, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crosson CE Intraocular pressure responses to the adenosine agonist cyclohexyladenosine: evidence for a dual mechanism of action. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42: 1837–1840, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Kater AW, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Gipson IK. Localization of smooth muscle myosin-containing cells in the aqueous outflow pathway. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 31: 347–353, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ethier CR The inner wall of Schlemm's canal. Exp Eye Res 74: 161–172, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ethier CR, Coloma FM. Effects of ethacrynic acid on Schlemm's canal inner wall and outflow facility in human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 40: 1599–1607, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleischhauer JC, Mitchell CH, Stamer WD, Karl MO, Peterson-Yantorno K, Civan MM. Common actions of adenosine receptor agonists in modulating human trabecular meshwork cell transport. J Membr Biol 193: 121–136, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabelt BT, Kaufman PL. Changes in aqueous humor dynamics with age and glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res 24: 612–637, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong H, Tripathi RC, Tripathi BJ. Morphology of the aqueous outflow pathway. Microsc Res Tech 33: 336–367, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gual A, Llobet A, Gilabert R, Borras M, Pales J, Bergamini MV, Belmonte C. Effects of time of storage, albumin, and osmolality changes on outflow facility (C) of bovine anterior segment in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 38: 2165–2171, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson M What controls aqueous humour outflow resistance? Exp Eye Res 82: 545–557, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson M, Erickson K. Mechanisms and routes of aqueous humor drainage. In: Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology, edited by Albert DM, and Jakobiec FA. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2000, p. 2577–2595.

- 23.Johnson M, Shapiro A, Ethier CR, Kamm RD. Modulation of outflow resistance by the pores of the inner wall endothelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 33: 1670–1675, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnstone MA Pressure-dependent changes in nuclei and the process origins of the endothelial cells lining Schlemm's canal. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 18: 44–51, 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karl MO, Fleischhauer JC, Stamer WD, Peterson-Yantorno K, Mitchell CH, Stone RA, Civan MM. Differential P1-purinergic modulation of human Schlemm's canal inner-wall cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C784–C794, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kregenow FM The response of duck erythrocytes to nonhemolytic hypotonic media. Evidence for a volume-controlling mechanism. J Gen Physiol 58: 372–395, 1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu JH Circadian rhythm of intraocular pressure. J Glaucoma 7: 141–147, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Z, Overby DR, Scott PA, Freddo TF, Gong H. The mechanism of increasing outflow facility by rho-kinase inhibition with Y-27632 in bovine eyes. Exp Eye Res 86: 271–281, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLaughlin CW, Macknight ADC, Civan MM. Effects of ouabain on ciliary epithelial cell composition. Abstr Intern Union Physiol Sci 651, 2001.

- 30.McLaughlin CW, Peart D, Purves RD, Carré DA, Macknight AD, Civan MM. Effects of HCO3− on cell composition of rabbit ciliary epithelium: a new model for aqueous humor secretion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 39: 1631–1641, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLaughlin CW, Zellhuber-McMillan S, Macknight AD, Civan MM. Electron microprobe analysis of ouabain-exposed ciliary epithelium: PE-NPE cell couplets form the functional units. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C1376–C1389, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLaughlin CW, Zellhuber-McMillan S, Macknight AD, Civan MM. Electron microprobe analysis of rabbit ciliary epithelium indicates enhanced secretion posteriorly and enhanced absorption anteriorly. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C1455–C1466, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLaughlin CW, Zellhuber-McMillan S, Peart D, Purves RD, Macknight AD, Civan MM. Regional differences in ciliary epithelial cell transport properties. J Membr Biol 182: 213–222, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitchell CH, Fleischhauer JC, Stamer WD, Peterson-Yantorno K, Civan MM. Human trabecular meshwork cell volume regulation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C315–C326, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Donnell ME, Brandt JD, Curry FR. Na-K-Cl cotransport regulates intracellular volume and monolayer permeability of trabecular meshwork cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 268: C1067–C1074, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Overby D, Gong H, Qiu G, Freddo TF, Johnson M. The mechanism of increasing outflow facility during washout in the bovine eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43: 3455–3464, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peppiatt CM, Howarth C, Mobbs P, Attwell D. Bidirectional control of CNS capillary diameter by pericytes. Nature 443: 700–704, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quigley HA Number of people with glaucoma worldwide. Br J Ophthalmol 80: 389–393, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raviola G, Raviola E. Intercellular junctions in the ciliary epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 17: 958–981, 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohen JW Experimental studies on the trabecular meshwork in primates. Arch Ophthalmol 69: 91–105, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scott PA, Overby DR, Freddo TF, Gong H. Comparative studies between species that do and do not exhibit the washout effect. Exp Eye Res 84: 435–443, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shearer TW, Crosson CE. Adenosine A1 receptor modulation of MMP-2 secretion by trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43: 3016–3020, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sit AJ, Nau CB, McLaren JW, Johnson DH, Hodge DO. Circadian variation of aqueous dynamics in adults 18–45 years old (Abstract). Assoc Res Vision Ophthalmol: 1141, 2007.

- 44.Soto D, Comes N, Ferrer E, Morales M, Escalada A, Pales J, Solsona C, Gual A, Gasull X. Modulation of aqueous humor outflow by ionic mechanisms involved in trabecular meshwork cell volume regulation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45: 3650–3661, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srinivas SP, Maertens C, Goon LH, Goon L, Satpathy M, Yue BY, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Cell volume response to hyposmotic shock and elevated cAMP in bovine trabecular meshwork cells. Exp Eye Res 78: 15–26, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tian B, Gabelt BT, Crosson CE, Kaufman PL. Effects of adenosine agonists on intraocular pressure and aqueous humor dynamics in cynomolgus monkeys. Exp Eye Res 64: 979–989, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toris CB, Yablonski ME, Wang YL, Camras CB. Aqueous humor dynamics in the aging human eye. Am J Ophthalmol 127: 407–412, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiederholt M, Stumpff F. The trabecular meshwork and aqueous humor reabsorption. In: Eye's Aqueous Humor: From Secretion to Glaucoma, edited by Civan MM. San Diego, CA: Academic, 1998, p. 163–202.