Abstract

We investigated the role of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels in β3-adrenoceptor (β3-AR)-induced relaxation in rat urinary bladder smooth muscle (UBSM). BRL 37344, a specific β3-AR agonist, inhibits spontaneous contractions of isolated UBSM strips. SR59230A, a specific β3-AR antagonist, and H89, a PKA inhibitor, reduced the inhibitory effect of BRL 37344. Iberiotoxin, a specific BK channel inhibitor, shifts the BRL 37344 concentration response curves for contraction amplitude, net muscle force, and tone to the right. Freshly dispersed UBSM cells and the perforated mode of the patch-clamp technique were used to determine further the role of β3-AR stimulation by BRL 37344 on BK channel activity. BRL 37344 increased spontaneous, transient, outward BK current (STOC) frequency by 46.0 ± 20.1%. In whole cell mode at a holding potential of Vh = 0 mV, the single BK channel amplitude was 5.17 ± 0.28 pA, whereas in the presence of BRL 37344, it was 5.55 ± 0.41 pA. The BK channel open probability was also unchanged. In the presence of ryanodine and nifedipine, the current-voltage relationship in response to depolarization steps in the presence and absence of BRL 37344 was identical. In current-clamp mode, BRL 37344 caused membrane potential hyperpolarization from −26.1 ± 2.1 mV (control) to −29.0 ± 2.2 mV. The BRL 37344-induced hyperpolarization was eliminated by application of iberiotoxin, tetraethylammonium or ryanodine. The data indicate that stimulation of β3-AR relaxes rat UBSM by increasing the BK channel STOC frequency, which causes membrane hyperpolarization and thus relaxation.

Keywords: BRL 37344; SR59230a; H89; iberiotoxin; detrusor; patch-clamp; spontaneous, transient, outward large-conductance current

contraction and relaxation of the urinary bladder smooth muscle (UBSM) is responsible for voiding and storage of urine. Ca2+ entry through dihydropyridine-sensitive L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ (CaV) channels is responsible for the initial depolarization phase of the UBSM spontaneous action potential and leads to an increase in the global intracellular Ca2+ concentration initiating UBSM phasic contractions (4, 17–20, 40). In UBSM, the repolarization phase of the action potential is mediated predominately by the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels (4, 18), whereas the resting membrane potential is regulated mainly by BK, voltage-gated K+, and KATP channels (1, 4, 18, 40, 46). Pharmacological inhibition of UBSM BK channels with the highly specific inhibitor, iberiotoxin (IBTX), increases the action potential duration and frequency, causes membrane potential depolarization (4, 18, 39), and increases the phasic contraction amplitude and tone (19, 40). Knockout mice lacking either the BK channel pore-forming α- or regulatory β-subunits exhibit increased UBSM phasic contractions and urine leakage (32, 40) similar to overactive bladder and urinary incontinence in humans. The fundamental role played by the BK channels in modulating UBSM function derives from their functionally antagonistic relationship with the L-type CaV channels that provide Ca2+ influx necessary to activate contraction. In general, inhibition of the UBSM BK channels leads to an increased membrane excitability and contractility, whereas their activation hyperpolarizes the membrane and decreases the contractility (for reviews, see Refs. 2, 4, and 7). Ca2+ is an important regulator not only of UBSM contractility but also of the UBSM BK channel activity (40, 42). In UBSM, BK channels are under the local control of so-called “Ca2+ sparks” caused by Ca2+ release from the ryanodine receptors (RyRs) of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), adjacent to the plasma membrane (20, 42). In both animal and human UBSM, the Ca2+ spark's activation of the BK channel is manifested in the form of spontaneous, transient, outward BK currents (STOCs), which can modulate the UBSM resting membrane potential (20, 39, 42).

Norepinephrine, released from sympathetic nerves, relaxes UBSM via stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs), which is the most plausible major mechanism that sustains bladder relaxation during filling (1, 15, 48). It is generally accepted that activation of β-ARs by agonists stimulates adenylyl cyclase to increase cAMP, which in turn, activates protein kinase A (PKA) to mediate UBSM relaxation. Recent studies show that agonist-induced stimulation of β-ARs causes activation of different K+ channels leading to membrane hyperpolarization and relaxation in various smooth muscle tissues (11, 45). In guinea pig UBSM, isoproterenol, a nonselective β-AR agonist, inhibits spontaneous action potentials and hyperpolarizes the membrane through PKA activation (35). In addition, relaxation of guinea pig UBSM in response to isoproterenol is mediated mainly by activation of the BK channels (27, 42). Our previous studies indicate that isoproterenol-induced BK channel activation in UBSM involves increased Ca2+ entry through L-type CaV channels and Ca2+ spark activity (42). The latter effect appears to be mediated by PKA-induced phosphorylation of phospholamban, which, when in a phosphorylated state, activates the SR Ca2+-pump, elevates SR Ca2+ load and thus RyRs and Ca2+ spark activity.

In rat and human UBSM, mRNA that codes for the three known β-ARs subtypes, β1-, β2-, and β3-ARs, has been detected (14, 24, 25, 34, 37, 43, 44). Increasing evidence suggests that the β-AR relaxation of UBSM is mediated mainly by β3-ARs (8, 15, 45, 48). However, the contribution of each of the three separate β-ARs to the BK channel activation in UBSM is unknown. A recent study on human myometrium reports that stimulation of β3-AR with 50–100 μM BRL 37344, a β3-AR-specific agonist, may cause activation of the BK channels and thus smooth muscle relaxation (10). In the urinary bladder, β3-AR stimulation may lead to BK channel activation, suggesting a functional link to facilitate UBSM relaxation.

To test this hypothesis, we employed functional studies on UBSM contractility and patch-clamp electrophysiology using BRL 37344 to stimulate the β3-ARs. We found that β3-AR-induced relaxation of UBSM is mediated by STOCs activation and membrane potential hyperpolarization. To further reveal the cellular mechanism of possible functional coupling between β3-ARs and the BK channels, we applied a variety of patch-clamp protocols and pharmacological tools to elucidate the different regulatory pathways at the level of BK channel Ca2+ signaling.

METHODS

Animal studies and UBSM tissue harvesting.

All animal studies were carried out in accordance with guidelines of the Animal Welfare Act and the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animals and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of South Carolina (Animal Use Protocol No. 1482). In the present study we used 77 adult Sprague-Dawley rats (54 males and 23 females), 3–5 mo old, with an average weight of 321.9 ± 7.6 g. Rats were euthanized with CO2, followed by exsanguination. The entire urinary bladder was removed and placed in ice-cold nominally Ca2+-free dissection solution (see Solutions and Drugs for composition). The bladder was then pinned to the bottom of a Sylgard-coated petri dish containing dissection solution. After the surrounding adipose and connective tissue were removed, the bladder was cut open with a longitudinal incision beginning from the urethral orifice. The entire mucosal layer of the bladder, including the urothelium, was removed, and the bladder was pinned with the serosal side up for dissection.

Contractility studies.

Up to eight small UBSM strips (1–2 mm wide and 5–6 mm long) were excised free from each bladder and transferred to a small petri dish containing dissection solution. Individual strips were placed in thermostatically controlled (37°C) tissue baths (5-ml volume). One end of the strip was attached to a stationary metal hook, whereas the other end was connected to a force-displacement transducer for isometric tension recording. The force generation by the muscle strips was recorded using a MyoMed myograph and MyoViewer data acquisition system (both from MedAssociates, St. Albans, VT). The UBSM strips were suspended under initial 10 mN tension. These procedures were carried out in a nominally Ca2+-free dissection solution. Five minutes later, the bath solution was replaced with a Ca2+-containing physiological saline solution (see Solutions and Drugs for composition). An equilibration period of at least 45–60 min followed, during which the bath solution was changed every 15 min. Most of the strips exhibited spontaneous phasic contractions during the equilibration period. Only strips that had stable controls and contracted spontaneously for at least 30–45 min were used for the experiments.

UBSM single cell isolation.

Small UBSM strips (1–2 mm wide and 5–7 mm long) were excised from the bladder wall. Several muscle strips were placed in a vial containing 2 ml of dissection solution supplemented with 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 1 mg/ml papain (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ), and 1 mg/ml dithioerythritol and incubated for 30–32 min at 37°C. After that, the tissue strips were transferred to 2 ml of dissection solution containing 1 mg/ml BSA, 1 mg/ml collagenase (type II from Sigma), and 100 μM CaCl2 for 9–14 min at 37°C. After incubation, the digested tissue was washed several times in dissection solution and then was gently triturated to yield single smooth muscle cells. Several drops of the solution containing the dissociated cells were then placed in a recording chamber. Cells were allowed to adhere to the glass bottom of the chamber for about 20 min. Most cells were elongated and had a bright, shiny appearance when examined with a phase-contrast microscope. The average UBSM cell capacitance was 27.7 ± 1.2 pF (n = 71 cells). Cells were used for patch-clamp recordings within 3–4 h after isolation.

Electrophysiological (patch-clamp) recordings.

The amphotericin-perforated, whole cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique was employed (16, 22). Whole cell currents were filtered using an eight-pole Bessel filter (model 900CT/9L8L; Frequency Devices) and recorded using an Axopatch 200B amplifier, Digidata 1440A, and pCLAMP version 10.1 software (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA). Patch-clamp pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) using a Narishige PP-830 vertical puller coated with sticky dental wax to reduce capacitance and polished with a Micro Forge MF-830 fire polisher (Narishige) to give a final tip resistance of ∼4–6 MΩ. STOCs were recorded while the UBSM cells were held at a holding potential (Vh) of −40 mV, a potential similar to the resting membrane potential of intact UBSM preparations (1, 41). To determine the mean amplitude and frequency of the transient BK currents, analysis was performed off-line using Clampfit of the pClamp software version 10.1. The threshold for the STOCs was set at 12 pA, which is more than three times the single-channel amplitude at −40 mV. STOCs were recorded over 10-min periods in the absence (control) and presence of BRL 37344. In a separate series of experiments, voltage-step protocols were used to elicit steady-state K+ outward current. UBSM cells were held at −70 mV and then depolarized from −40 mV to +80 mV at 20 mV steps of 200-ms duration. The steady-state K+ outward currents were recorded in the presence of ryanodine (30 μM) and thapsigargin (100 nM), which indirectly block STOCs. Nifedipine (1 μM) was also used to block the L-type CaV channels. For the voltage-step protocols, 4–6 controls were recorded and the data were averaged. Only cells with stable control currents in response to depolarization steps within at least 15 min were used to study BRL 37344 effects. After BRL 37344 administration, voltage-step protocols were applied every 1–2 min for at least a 15-min period, and steady-state K+ outward currents were recorded. The average steady-state K+ current value during the last 50 ms of the 200-ms depolarization step was used to plot current-voltage relationships.

In another series of experiments, single BK channel activity was recorded from UBSM cells in whole cell mode as previously described (42). The large amplitude and low open probability (Po) of the BK channel in UBSM cells permits the measurement of single BK channel currents with the use of the amphotericin-perforated, whole cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique when the cells’ native environment and signal transduction pathways were preserved. To observe single BK channel currents, Ca2+ sparks, and hence STOCs were prevented by blocking RyRs and SR Ca2+-pump with ryanodine (30 μM) and thapsigargin (100 nM), respectively. The L-type CaV channels were inhibited with nifedipine (1 μM), and the cells were clamped at 0 mV, a potential at which L-type CaV and voltage-gated K+ channels are largely inactivated (46). Under these conditions, single UBSM BK channels were identified by their characteristic large, single-channel conductance, voltage dependence, and sensitivity to IBTX (42). Single BK channel Po was calculated from continuous recordings of 7- to 10-min intervals in the absence (control) and presence of BRL 37344. Because the total number of BK channels (N) for each individual cell is unknown, the cell NPo was normalized to the cell capacitance (measured as NPo/pF). In some cells, at the end of the recordings, IBTX (200 nM) was applied to confirm that the recorded currents were through BK channels. UBSM cell membrane potential was recorded using the current-clamp mode of the patch-clamp technique. All patch-clamp experiments were carried out at room temperature (22–23°C).

Solutions and drugs.

The nominally Ca2+-free dissection solution had the following composition (in mM): 80 monosodium glutamate, 55 NaCl, 6 KCl, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, and 2 MgCl2, pH 7.3, adjusted with NaOH. The Ca2+-containing physiological salt solution was prepared daily and contained (in mM): 119 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 24 NaHCO3, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, and 11 glucose, and was aerated with 95% O2-5% CO2 to obtain pH 7.4. The extracellular (bath) solution used in the electrophysiological experiments contained (in mM): 134 NaCl, 6 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The pipette solution contained (in mM): 110 potassium aspartate, 30 KCl, 10 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 0.05 EGTA, pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH and supplemented with freshly dissolved (every 1–2 h) 200 μg/ml amphotericin-B. Atropine, nifedipine, and tetraethylammonium (TEA) were purchased from Acros Organics; BRL 37344, dithioerythritol, H89, IBTX, SR59230A, tetrodotoxin were from Sigma; ryanodine (ryanodine, 9, 21-dehydro-) was from Calbiochem; and bovine serum albumin, thapsigargin, and amphotericin-B were from Fisher Scientific.

Data analysis and statistics.

UBSM contraction data were analyzed using MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft). This software has allowed us to analyze the changes in all four major parameters of the UBSM phasic and tonic contractions (tone)-phasic contraction amplitude, phasic contractions frequency, net muscle force, and muscle tone. Data were further analyzed with GraphPad Prism (version 4) and presented using CorelDraw Graphic Suite X3 (Corel) software. Cumulative concentration response curves for BRL 37344 were obtained by adding increasing concentrations of the drugs directly to the tissue baths every 10 min. A 3-min period from the 7th to the 10th min after exposure to each drug concentration was taken as the analysis period. To compare the phasic contractions parameters, data were normalized to the spontaneous contractions and expressed as percentages. Net muscle force (muscle force integral) was determined by integrating the area under the curve of the phasic contractions component. Tone was determined by measuring changes of the phasic contraction baseline curve. Patch-clamp electrophysiological data were analyzed with Clampfit version 10.1.

Summary data are presented as means ± SE for n, the number of separate UBSM strips or single cells, respectively, and N, the number of individual rats. The data were assessed for statistical significance using the one-tailed paired Student's t-test. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 leads to inhibition of UBSM spontaneous contractility: role of the BK channel and PKA.

In isolated rat UBSM strips, stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 inhibits tonic contractions induced by membrane depolarization due to increased external K+ (8, 13, 28, 38). High external K+ (15–50 mM KCl) restrains the function of the K+ channels, including the BK channel, thus masking the native mechanism of β3-AR-induced relaxation of the bladder. In fact, the effects of β3-AR stimulation with BRL 37344 on UBSM spontaneous phasic and tonic contractions in a physiological external K+ solution have, to our knowledge, never been studied.

Here, we sought to investigate whether a pharmacological stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 leads to inhibition of the physiologically relevant spontaneous phasic and tonic contractions that normally decreased during the bladder-filling phase (for a review, see Ref. 1), and to further investigate the underlying mechanism. It is well known that UBSM contractions are modulated by neurotransmitters, released from autonomic nerves located in the bladder wall. To minimize any possible effects caused by neurotransmitter release, all experiments were performed in the presence of 1 μM tetrodotoxin, a neuronal Na+ channel blocker. Because BRL 37344 was also reported to have some antimuscarinic effects in rat and guinea pig UBSM (5, 28), we also applied 1 μM atropine, a nonselective muscarinic receptor antagonist.

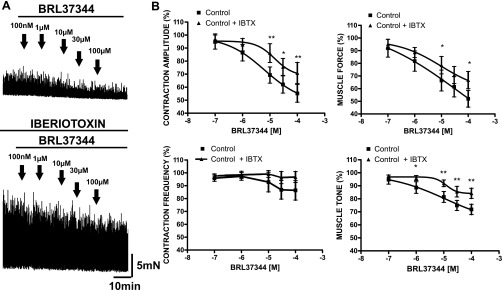

In isolated rat UBSM strips, a selective stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 (100 nM-100 μM) caused a concentration-dependent decrease in spontaneous phasic contractions and muscle tone (Fig. 1). Figure 1 also shows the cumulative concentration response curves for BRL 37344 effects on the spontaneous phasic contractions amplitude, frequency, net muscle force, and muscle tone in rat UBSM strips. As illustrated, BRL 37344 (100 nM-100 μM) inhibited the phasic contraction's amplitude and net muscle force, and significantly reduced the muscle tone in isolated UBSM strips. In UBSM, a phasic contraction reflects an elevation of Ca2+ entry via L-type CaV channels caused by a single action potential or a burst of action potentials (17). The amplitude of a phasic contraction depends on the increase in Ca2+ entry caused by membrane depolarization during an action potential, whereas the duration of a phasic contraction depends on the single action potential duration or on a whole burst of action potentials (17, 18). The frequency of phasic contractions reflects mechanisms that temporarily cause action potentials to cease, such as an increase in K+ channel conductance (4, 17, 40–42).

Fig. 1.

Blocking the BK channel with iberiotoxin (IBTX) decreases the inhibitory effect of BRL 37344 on the spontaneous contractile activity in isolated UBSM strips. A: original recordings illustrating the inhibitory effect of BRL 37344 (100 nM-100 μM) on the spontaneous contractions in the absence (top trace) and presence (bottom trace) of 200 nM IBTX. B: concentration response curves for the inhibitory effect of BRL 37344 (100 nM-100 μM) on the spontaneous phasic contraction amplitude, frequency, net muscle force, and muscle tone in the presence and absence of 200 nM IBTX. In the presence of IBTX, the concentration response curves were shifted right. Spontaneous contractions were taken as 100%. Values are means ± SE. (n = 7, N = 5; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). TTX (1 μM) and atropine (1 μM) were present throughout the experiments.

We have previously shown that nonselective stimulation of all three β-ARs subtypes with isoproterenol leads to BK channel activation (42). Therefore, it was of interest to investigate whether the BK channel is also involved in the β3-AR-mediated relaxation of UBSM spontaneous contractility. Blocking the BK channel with 200 nM IBTX increased the spontaneous phasic contraction amplitude and the overall UBSM contractility (Fig. 1). In the presence of 200 nM IBTX, the concentration response curves for BRL 37344 (100 nM-100 μM) were shifted to the right. The effects were statistically significant at BRL concentrations > 10 μM (Fig. 1).

Because the BRL 37344 concentration response experiments are extended experiments conducted within a 50-min time frame, time control experiments were performed in parallel for the spontaneous and IBTX-induced phasic contractions in which no BRL 37344 was added. The data for the time controls summarized in Table 1 indicate that both spontaneous and IBTX-induced contractions remained stable during the time course for the BRL 37344 concentration response experiments. Therefore, BRL 37344 indeed had inhibitory effects on the contraction parameters as illustrated in Fig. 1, and they were not due to rundown of the UBSM preparations.

Table 1.

Time controls, without BRL 37344 added, were measured 50 min after the initial control (taken to be 100%) for the spontaneous contractions and 50 min after the IBTX application for the IBTX-induced contractions, respectively

| Contraction Amplitude | Contraction Frequency | Net Muscle Force | Tone | n, N, P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous contractions time control | 102.7%±6.4% | 98.9%±8.1% | 110.0%±7.0% | 100.1%±1.9% | 5, 4, P > 0.05 |

| IBTX-induced contractions time control | 91.4%±5.4% | 104.9%±1.8% | 91.0%±4.8% | 96.8%±1.8% | 5, 3, P > 0.05 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of separate urinary bladder smooth muscle (UBSM) strips; N, the number of individual rats. The 50-min time period is equivalent to the time period for the BRL 37344 concentration-response curves. TTX (1 μM) was present throughout the experiments.

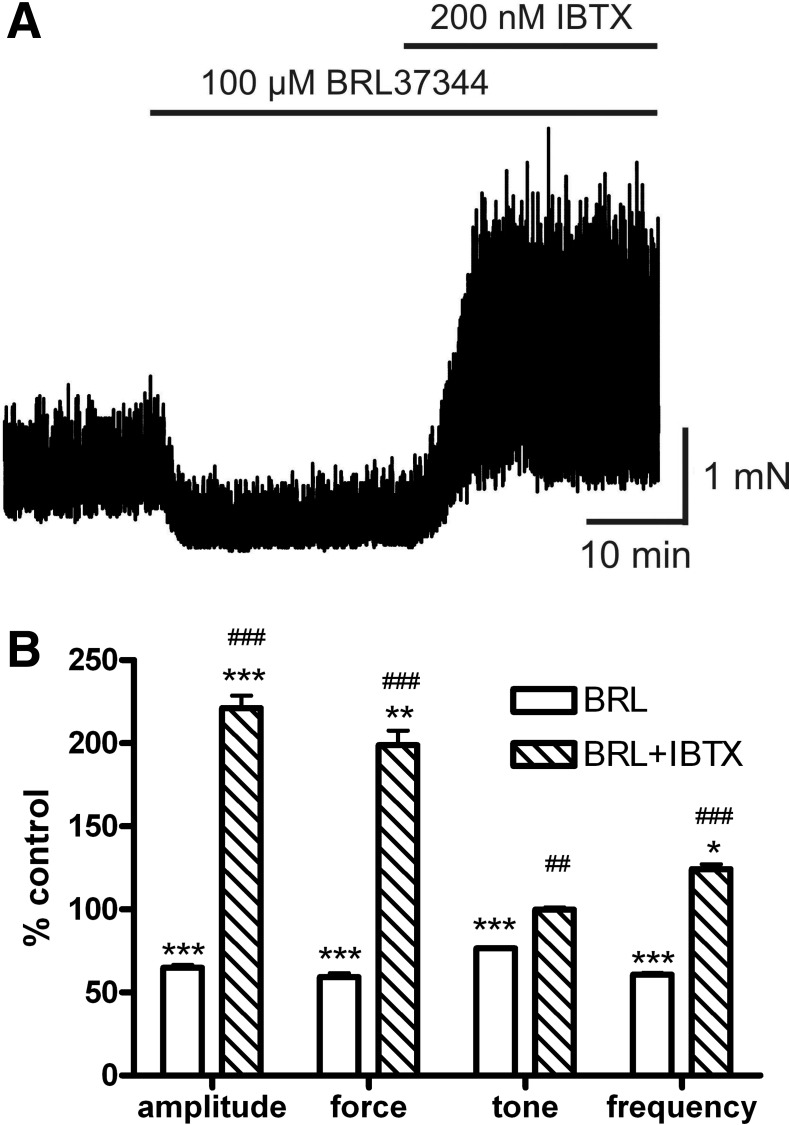

In another experimental series, we first applied a single concentration of BRL 37344 (100 μM) to achieve maximum inhibition on the spontaneous UBSM contractions. In the presence of 100 μM BRL 37344, application of IBTX (200 nM) caused not only complete recovery of all contraction parameters (amplitude, force, frequency, and tone) to the level of spontaneous contractility but further significantly increased contraction amplitude and frequency above the level of spontaneous contractions (Fig. 2). This experimental series indicates that pharmacological blockade of the BK channel overcomes the inhibitory effect of BRL 37344 on spontaneous contractions, suggesting a functional interaction between β3-ARs and the BK channels. These experiments clearly indicate the key role of the BK channel in UBSM relaxation mediated by the β3-ARs.

Fig. 2.

IBTX overcomes the inhibitory effect of BRL 37344 on the spontaneous contractile activity and further increases contraction amplitude and frequency in isolated UBSM strips. A: original recordings illustrating the inhibitory effect of BRL 37344 (100 μM) on the spontaneous contractions and that IBTX (200 nM) restores and even increases phasic contraction amplitude and frequency. B: summary data for the inhibitory effect of BRL 37344 (100 μM) on the spontaneous phasic contraction amplitude, net muscle force, muscle tone, and frequency; and the effect of IBTX (200 nM) in the presence of BRL 37344 (100 μM). Spontaneous contractions were taken as 100%. Values are means ± SE (n = 9, N = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. BRL 37344). TTX (1 μM) and atropine (1 μM) were present throughout the experiments.

To confirm that the effect of BRL 37344 is mediated via β3-ARs, we used the β3-AR-specific antagonist SR59230A. In this experimental series, UBSM strips were first exposed to 100 μM BRL 37344 to achieve a maximal relaxation, and then the drug was washed out. After recovery of spontaneous contractility, the strips were pretreated with 10 μM SR59230A for 30 min and 100 μM BRL 37344 was applied again. In the presence of 10 μM SR59230A, the inhibitory effect of BRL 37344 was significantly reduced, indicating that BRL 37344 effects are mediated via β3-ARs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Inhibitory effect of 100 μM BRL37344 on UBSM spontaneous contractility in the absence and presence of 10 μM SR59230A

| Control No SR59230A, %Spontaneous Contractions | +10 μM SR59230A, %Spontaneous Contractions | n, N, P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contraction amplitude | 54.1±5.0 | 80.3±10.5 | 9, 5, P < 0.01 |

| Contraction frequency | 50.8±7.9 | 83.9±4.4 | 9, 5, P < 0.01 |

| Net muscle force | 46.5±4.6 | 80.5±8.9 | 9, 5, P < 0.001 |

| Tone | 75.4±4.1 | 84.5±2.6 | 9, 5, P < 0.01 |

Values are means ± SE. n, number of separate UBSM strips; N, the number of individual rats. Spontaneous contractions were taken as 100%. TTX (1 μM) and atropine (1 μM) were present throughout the experiments.

To confirm that stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 leads to PKA activation, we used the PKA-specific inhibitor H89. This inhibitor was selected because of its membrane permeability. In this experimental series, we tested two concentrations of BRL 37344, 10 μM and 100 μM. UBSM strips were first probed by a given BRL 37344 concentration and after a maximal relaxation was achieved, the drug was washed out. The UBSM strips were then pretreated with 10 μM H89 for 30 min, and the same concentration of BRL 37344 was applied. In the presence of 10 μM H89, the tone of UBSM strips was significantly inhibited at both concentrations used, indicating that at least the BRL 37344 reduction of tone is mediated by PKA (Table 3).

Table 3.

Inhibitory effect of BRL37344 (10–100 μM) on UBSM spontaneous contractility in the absence and presence of 10 μM H89

| Control No H89, %Spontaneous Contractions | +10 μM H89, %Spontaneous Contractions | n, N, P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 μM BRL 37344 | |||

| Contraction amplitude | 67.9±5.7 | 71.2±7.8 | 6, 4, P > 0.05 |

| Contraction frequency | 64.1±6.2 | 76.1±7.0 | 6, 4, P > 0.05 |

| Net muscle force | 70.9±7.2 | 71.8±9.2 | 6, 4, P > 0.05 |

| Tone | 78.2±2.5 | 95.5±4.3 | 6, 4, P < 0.05 |

| 100 μM BRL 37344 | |||

| Contraction amplitude | 53.4±6.3 | 55.0±3.8 | 7, 4, P > 0.05 |

| Contraction frequency | 62.7±12.1 | 71.4±7.9 | 7, 4, P > 0.05 |

| Net muscle force | 52.5±8.0 | 53.4±3.9 | 7, 4, P > 0.05 |

| Tone | 74.7±2.3 | 88.1±1.8 | 7, 4, P < 0.05 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of separate UBSM strips; N, the number of individual rats. Spontaneous contractions were taken as 100%. TTX (1 μM) and atropine (1 μM) were present throughout the experiments.

To further reveal the cellular mechanism of BK channel activation upon β3-AR stimulation, we performed perforated whole cell, patch-clamp experiments on isolated UBSM cells under various experimental conditions. The perforated mode of the patch-clamp technique maintains the native environment of the cell, preserving the signal transduction pathways intact. In all electrophysiological experiments below, we used a single BRL 37344 concentration of 100 μM. At this concentration, BRL 37344 reached a maximal effect on UBSM contractility (Figs. 1–2), and, at this concentration, BRL 37344 has previously been shown to increase BK channel activity in human myometrium (10).

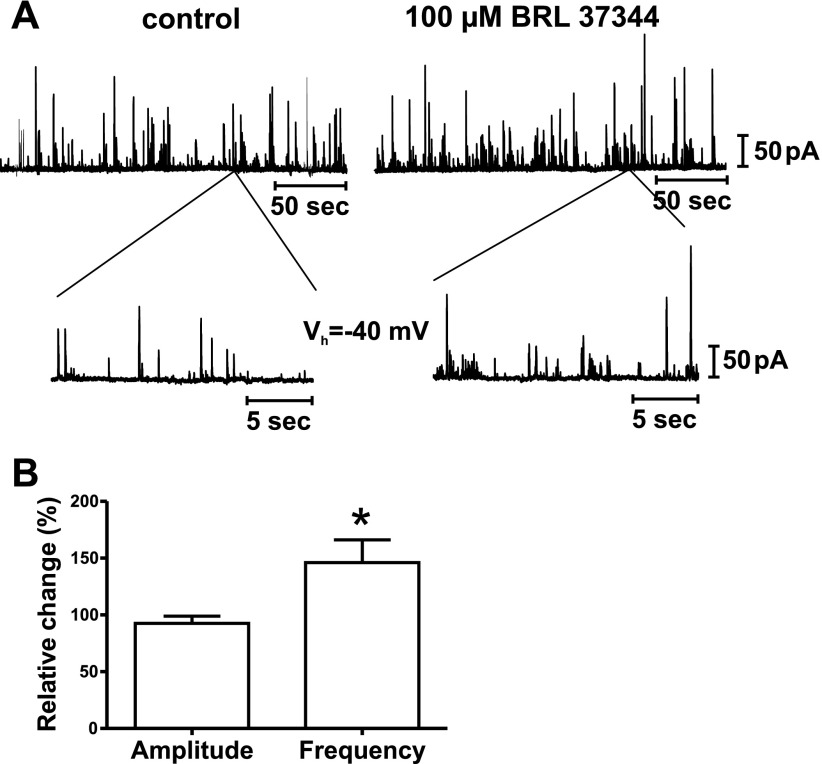

Stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 causes activation of STOCs in single, isolated UBSM cells.

In UBSM, Ca2+ sparks activate the closely located BK channels, thus causing STOCs (20, 42). Therefore, STOCs are indicative for Ca2+ sparks. To examine the effect of BRL 37344 on STOCs, STOCs were recorded from single, isolated UBSM cells that were voltage-clamped at −40 mV (see methods). BRL 37344 (100 μM) caused a sustained increase in STOC frequency by 46.0 ± 20.1% vs. control (n = 5, N = 5; P < 0.05; Fig. 3), whereas the STOC amplitude was unaffected (92.5 ± 6.4% vs. control, n = 5, N = 5; P > 0.05; Fig. 3). These results support the idea that in UBSM, stimulation of β3-ARs can activate BK channels through STOCs activation. STOCs activation is likely to move the UBSM resting membrane potential away from the threshold of action potential activation and significantly inhibit the action potentials and the associated phasic contractions.

Fig. 3.

Stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 increases STOCs activity in isolated UBSM cells. A: original recordings illustrating that BRL 37344 (100 μM) increases the frequency of STOCs in single UBSM cells. A portion of the experiment is shown on an expanded time scale before and 8 min after BRL 37344 application. Whole cell currents were recorded with the perforated patch-clamp technique at a holding potential (Vh) of −40 mV. B: summary data illustrating the increase in STOCs frequency in the presence of BRL 37344 (100 μM). STOCs frequency and average STOCs amplitude under control conditions were taken as 100%, respectively, and indicated on the y-axis. Values are means ± SE (n = 5, N = 5; *P < 0.05 vs. control).

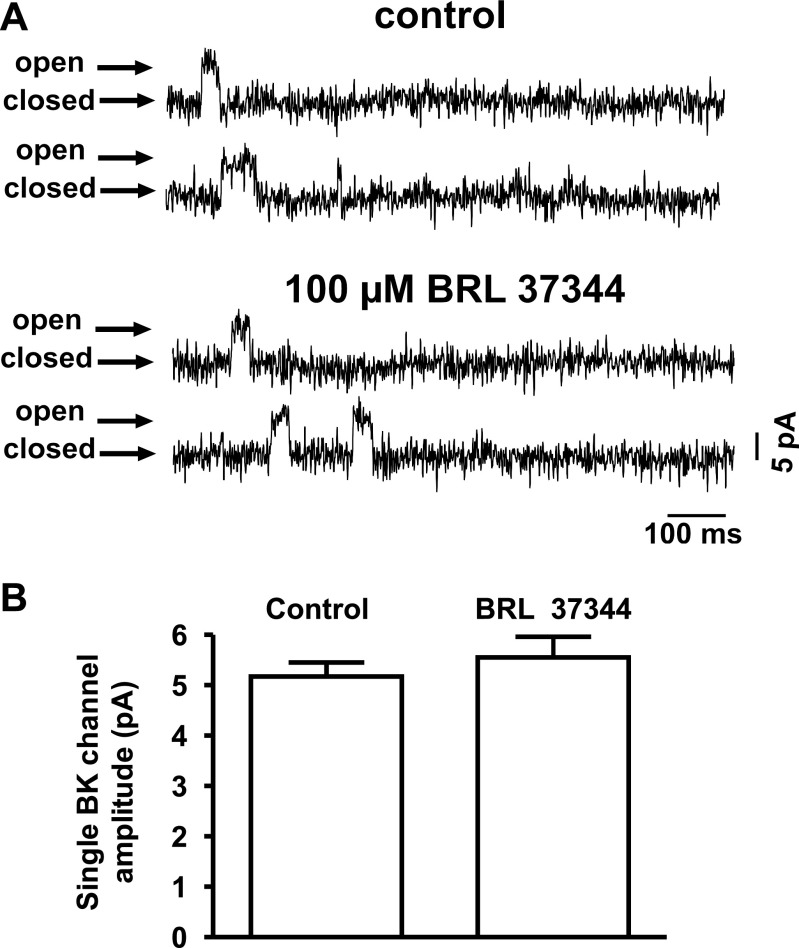

Under conditions of blocked Ca2+ sources for BK channel activation, stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 does not change single BK channel activity.

The observed elevation of STOCs frequency could be explained by a BRL 37344-induced increase in Ca2+ spark frequency. An alternative hypothesis would be an elevation of the BK channel Po caused by direct BRL 37344 effects on the channel or by PKA-induced phosphorylation of the channel. To test the effects of BRL 37344 on UBSM BK channels in their native physiological environment, single-channel currents were recorded from isolated UBSM cells in whole cell mode, using the amphotericin-perforated patch-clamp technique (see methods). In whole cell mode at Vh = 0 mV, BRL 37344 (100 μM) did not significantly change the single BK channel Po: 0.0022 ± 0.0018 NPo/pF (control) and 0.0019 ± 0.0012 NPo/pF (BRL 37344) (n = 5, N = 3; P > 0.05; Fig. 4). The single BK channel current amplitude was not affected by 100 μM BRL 37344 at 0 mV: 5.17 ± 0.28 pA (control) and 5.55 ± 0.41 pA (BRL 37344) (n = 5, N = 3; P > 0.05; Fig. 4). These results are consistent with the idea that in rat UBSM cells, BRL 37344-induced activation of STOCs is not due to any direct effect on the BK channel or changes in the BK channel Po.

Fig. 4.

Stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 does not significantly change the amplitude and open probability (Po) of single BK channels under conditions when the Ca2+ sources for BK channel activation were pharmacologically inhibited. Single BK channel currents were recorded with the whole cell, perforated, patch-clamp technique from single smooth muscle cells at 0 mV holding potential. A: shown is a series of BK channel openings from a single cell recorded before (control) and after application of 100 μM BRL 37344. B: summary data illustrating lack of BRL 37344 (100 μM) effect on the single BK channel amplitude. Values are means ± SE (n = 5, N = 3; P > 0.05). Ryanodine (30 μM), thapsigargin (100 nM), and nifedipine (1 μM) were present throughout the experiments.

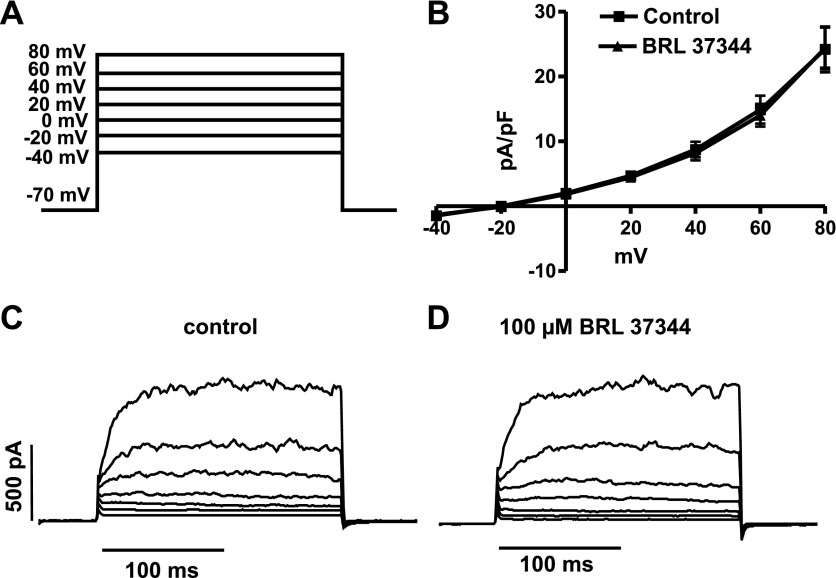

Under conditions of blocked Ca2+ sources for BK channel activation, stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 does not change the steady-state K+ current.

To examine further whether stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 leads to activation of the total steady-state K+ current, we performed experiments on isolated UBSM cells using voltage-step protocols and the whole cell, perforated, patch-clamp technique. From Vh = −70 mV, voltage-step depolarizations with 200-ms duration, applied in 20-mV increments from −40 to +80 mV induced steady-state K+ currents (Fig. 5). We have previously shown that the majority of these voltage-step-induced steady-state K+ currents consist of a steady-state BK current component due to their high sensitivity to IBTX (42). As in the previous experimental series on single BK channel activity, all known extra- and intracellular Ca2+ sources for BK channel activation were eliminated (see methods). Under these conditions, stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 (100 μM) did not activate the depolarization-induced (−40 to +80 mV) steady-state outward K+ currents (Fig. 5). As illustrated in Fig. 5, the current-voltage relationships for the voltage-step-induced steady-state K+ currents in the presence and absence of 100 μM BRL 37344 were largely unaffected (n = 8, N = 6; P > 0.05). Furthermore, we repeated the same experimental series in the presence of 200 nM IBTX, using the same voltage-step protocol under conditions of blocked Ca2+ sources. Again, the current-voltage relationships for the voltage-step-induced, IBTX-insensitive, steady-state K+ currents in the presence and absence of 100 μM BRL 37344 were largely unaffected (n = 4, N = 4; P > 0.05; data not illustrated). These experiments suggest that stimulation of β3-ARs does not activate the steady-state BK current or any other voltage-dependent, steady-state K+ currents directly but rather requires functional Ca2+ sources for BK channel activation.

Fig. 5.

Stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 does not increase the voltage-step-induced steady-state K+ currents in single UBSM cells under conditions when the Ca2+ sources for BK channel activation were pharmacologically inhibited. A: illustration of the voltage-step protocol that was applied to record whole cell, steady-state K+ currents using the perforated-patch technique at a Vh of −70 mV. B: current-voltage relationships for the depolarization-induced steady-state K+ currents in the presence and absence of 100 μM BRL 37344 were unchanged. Values are means ± SE (n = 8, N = 6; P > 0.05). Original recordings illustrating the steady-state K+ currents in response to voltage-step depolarization (−40 to +80 mV) before (C; control) and after application of 100 μM BRL 37344 (D). Ryanodine (30 μM), thapsigargin (100 nM), and nifedipine (1 μM) were present throughout the experiments.

Stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 causes UBSM cell membrane potential hyperpolarization mediated by the BK channels.

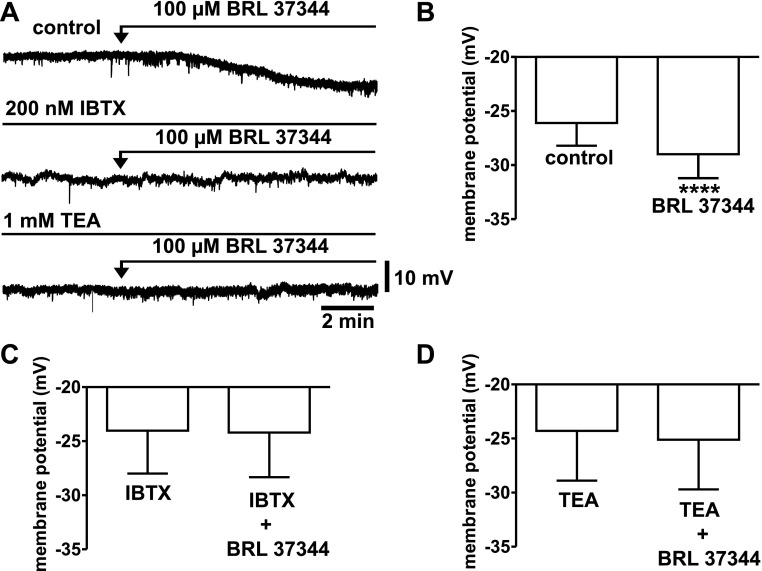

In UBSM, the BK channel contributes to the maintenance of the resting membrane potential to some extent (18, 39). The increased STOCs frequency caused by BRL 37344-induced β3-ARs stimulation may lead to membrane potential hyperpolarization. To test this hypothesis, we performed current-clamp experiments using the perforated whole cell, patch-clamp technique. Under current-clamp conditions, stimulation of the β3-AR with 100 μM BRL 37344 hyperpolarized the resting membrane potential from −26.1 ± 2.1 mV (control) to −29.0 ± 2.2 mV (BRL 37344; n = 18; N = 12; P < 0.0001; Fig. 6). The BRL 37344-induced hyperpolarization was prevented by preliminary application of the BK channel-specific inhibitor, IBTX (200 nM) or by nonspecific BK channel inhibition with 1 mM TEA. In the presence of 200 nM IBTX, BRL 37344 (100 μM) did not significantly change the resting membrane potential: −24.0 ± 4.0 mV (IBTX control) and −24.2 ± 4.1 mV (BRL 37344) (n = 9, N = 3; P > 0.05; Fig. 6). In the presence of 1 mM TEA, BRL 37344 (100 μM) also did not significantly change the resting membrane potential: −24.3 ± 4.6 mV (TEA control) and −25.1 ± 4.6 mV (BRL 37344) (n = 8, N = 3; P > 0.05; Fig. 6). These experiments indicate that BRL 37344-induced STOCs activation is associated with membrane potential hyperpolarization leading to an inhibition of UBSM spontaneous contractility.

Fig. 6.

In isolated UBSM cells, stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 causes membrane potential hyperpolarization, which was prevented by blocking the BK channels with 200 nM IBTX or 1 mM TEA. A: original recordings illustrating the BRL 37344 (100 μM) hyperpolarizing effect on the resting membrane potential under control conditions (top trace), and lack of an hyperpolarizing effect in the presence of 200 nM IBTX (middle trace), or 1 mM TEA (bottom trace). Resting membrane potential was recorded in current-clamp mode of the perforated-patch technique. B: summary data illustrating BRL 37344 (100 μM) hyperpolarizing effect under control conditions. Values are means ± SE (n = 11, N = 6; ****P < 0.0001). C: summary data illustrating lack of BRL 37344 (100 μM) hyperpolarizing effect in the presence of 200 nM IBTX (n = 9, N = 3; P > 0.05). D: summary data illustrating lack of BRL 37344 (100 μM) hyperpolarizing effect in the presence of 1 mM TEA (n = 8, N = 3; P > 0.05).

In another experimental series, the BRL 37344-induced (100 μM) hyperpolarization was eliminated by subsequent application of IBTX (200 nM): control (−26.8 ± 2.3 mV); BRL 37344 (−28.7 ± 2.7 mV; P < 0.05 vs. control); BRL 37344 and IBTX (−27.3 ± 2.3 mV n = 9, N = 8; P < 0.05 vs. BRL 37344; P > 0.05 vs. control). This experimental series confirms that pharmacological blockade of the BK channel overcomes the hyperpolarizing effect of BRL 37344 in isolated UBSM cells, suggesting a functional interaction between β3-ARs and the BK channels at the level of the resting membrane potential.

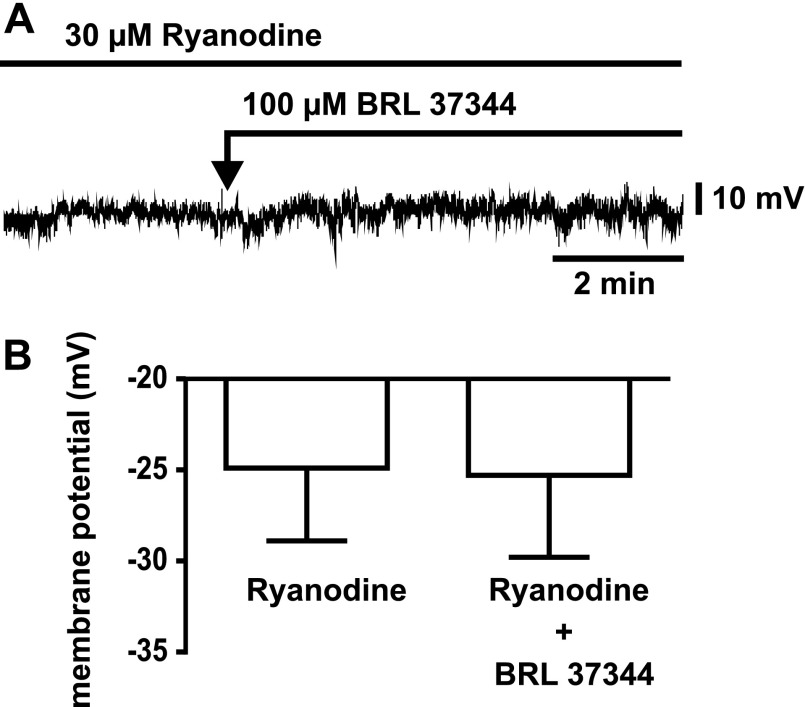

In the last experimental series, illustrated in Fig. 7, the BRL 37344-induced (100 μM) hyperpolarization was not observed in the presence of 30 μM ryanodine (control, −24.9 ± 4.0 mV; BRL 37344, −25.3 ± 4.5 mV; n = 7, N = 5; P < 0.05 vs. control). This final experimental series confirms that pharmacological blockade of the RyR overcomes the hyperpolarizing effect of BRL 37344, indicating that the RyRs are required to facilitate the functional link between β3-ARs and the BK channels.

Fig. 7.

In isolated UBSM cells, stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 does not cause membrane potential hyperpolarization when the RyRs are inhibited. A: original recordings illustrating the lack of a BRL 37344 (100 μM) hyperpolarizing effect on the resting membrane potential in the presence of 30 μM ryanodine. Resting membrane potential was recorded in current-clamp mode of the perforated-patch technique. B: summary data illustrating lack of a BRL 37344 (100 μM) hyperpolarizing effect in the presence of 30 μM ryanodine (n = 7, N = 5; P > 0.05 vs. control).

DISCUSSION

The present study reveals important details of a fundamental regulatory pathway involved in the control of urinary bladder contractility; β3-ARs and BK channels are functionally coupled to promote UBSM relaxation via BK channel activation upon β3-ARs stimulation. These results further uncover the complex Ca2+-dependent mechanism of this physiological coupling, which involves activation of STOCs frequency (Fig. 3), leading to UBSM cell membrane hyperpolarization (Fig. 6) and inhibition of UBSM spontaneous phasic contractions and tone (Figs. 1 and 2).

As key regulators of UBSM membrane excitability, BK channels control the opening and closing of L-type CaV channels, thereby affecting UBSM contractility. Our experiments on the spontaneous phasic and tonic contractions showed that stimulation of β3-ARs with BRL 37344 led to concentration-dependent inhibition of phasic contraction amplitude, net muscle force, and muscle tone. BRL 37344 (300 μM) is also effective at inhibiting spontaneous contractions of isolated whole guinea pig bladder (15). In rat UBSM, the potential inhibitory effect on the overall spontaneous contractility upon β3-ARs stimulation with FR165101 and the possible involvement of the BK channel in this process has previously been suggested (47). Here, we have further separated and characterized the β3-AR inhibitory effects on the different contraction parameters. In the presence of IBTX, a rightward shift in the concentration response curves was observed, indicating the importance of the BK channel in the BRL 37344 inhibitory effect on contractility (Fig. 1).

Our current-clamp experiments suggest a prominent role of β3-ARs in controlling the UBSM excitability by utilizing the BK channel (Figs. 6 and 7). The increase in STOCs frequency upon β3-ARs stimulation contributes to membrane hyperpolarization and moves the UBSM resting membrane potential away from the threshold of action potential activation and thus has significant inhibitory effects on action potentials and related phasic contractions. Our experiments on whole cell, K+ steady-state currents (Fig. 5) and single BK channel recordings (Fig. 4) do not support a mechanism for a direct activation of the BK channels by BRL 37344 in intact cells with blocked sources of Ca2+ necessary for BK channel activation. Rather, they support the concept that β3-AR stimulation activates BK channels by increasing STOCs activity in UBSM cells. Collectively, our data indicate that the physiological coupling between the β3-ARs and BK channels, which is responsible for UBSM hyperpolarization and relaxation, requires active sources of Ca2+ for BK channel activation.

Although cAMP/PKA is the main signal transduction pathway that mediates β3-AR effects, both PKA-dependent and -independent mechanisms have been proposed to operate in UBSM (11, 12, 45, 47, 48). Most of the information for a PKA-independent mechanism, however, comes from indirect evidence on UBSM contractility (12, 47, 48). Uchida et al. (47) have further indicated that in “noncontracted” UBSM (spontaneous contractions), relaxation mediated via β3-ARs is achieved solely by a cAMP-dependent mechanism. We have previously found that forskolin increases single BK channel Po, whereas nonspecific activation of all β-ARs with isoproterenol is not sufficient to increase BK channel Po (42). It has been shown that physiological coupling between β2-ARs and BK channels occurs by PKA-mediated phosphorylation of the channel pore-forming α-subunit (36). It has also been reported that β2-ARs are closely associated with the BK channel α-subunit and a PKA-anchoring protein to mediate the β2-AR-agonist responses in UBSM (29). Our data do not provide evidence for a similar colocalization and direct coupling between the β3-ARs and BK channels in rat UBSM. Instead, the functional coupling between the β3-ARs and BK channels in UBSM utilizes BK channel ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ signaling mechanisms at the SR level. Our data indicates that BRL 37344-induced hyperpolarization is eliminated in the presence of ryanodine (Fig. 7). BRL 37344, via PKA activation, can act directly on the RyRs and/or indirectly by phospholamban phosphorylation. Our data show that the BRL 37344 relaxant effect on the UBSM tone is inhibited by H89, consistent with a role for PKA. In skeletal and cardiac muscle, PKA-phosphorylated phospholamban activates the SR Ca2+-pump and elevates SR Ca2+ load, which increases the Po of RyRs channels (9). PKA can also increase the Po of the RyRs channel and thus RyRs activity by direct phosporylation of the receptor (9). Most likely, the observed BRL 37344-induced increase in STOC activity may use both mechanisms.

BK channel activation upon β3-AR stimulation with BRL 37344 (50–100 μM) has been observed in human myometrium (10). Although this study by Doheny et al. (10), was similarly focused, our methodology is more refined for elucidating mechanistic details of the pathway of BK channel activation. The major difference between the two approaches is our utilization of pharmacological tools, such as ryanodine, thapisgargin, and nifedipine, to dissect the different sources of Ca2+ for BK channel activation. We have also distinguished between STOCs and steady-state BK currents, which have fundamentally different mechanisms of origin and regulation (20, 42). Additionally, we have improved upon the electrophysiological protocols by completing the experiments in more physiologically relevant conditions. For example, we utilized a Vh = 0 mV, instead of Vh = +40 mV. At Vh = +40 mV, the BK channel is exceedingly activated (40), and further activation upon pharmacological stimulation is unlikely to occur. Also, we used recording intervals of 7–10 min, which provide a more accurate determination of Po than recording intervals of ∼10 s. Finally, the unjustifiably high Ca2+ concentration in the pipette used by Doheny et al. (10) may be a source of contaminating Ca2+ activator for the BK channel, whereas our conditions of 0 Ca2+ + 0.05 mM EGTA (to eliminate any residual Ca2+) do not provide this interference. These important experimental details allowed us to identify with high accuracy the intrinsic mechanisms of the functional link between β3-ARs and BK channels in rat UBSM. In addition, Doheny et al. (10) did not record any STOCs in human myometrium. Therefore, tissue and/or species differences in the mechanism of BK channel activation upon β3-AR stimulation in rat UBSM and human myometrium cannot be ruled out.

Overactive bladder is a condition characterized by symptoms of urgency, frequency, nocturia, and increased UBSM phasic contractions that often follow bladder outlet obstruction due to prostate enlargement (for review, see Refs. 1 and 2). The etiology of overactive bladder is unknown and the current therapies are limited to antimuscarinics that are largely ineffective with numerous undesirable side effects. Therefore, there is a need to develop alternative therapeutic approaches with novel mechanisms of action.

Because the BK channel is a key modulator of UBSM excitability in experimental animals, mutations of this channel may cause overactive bladder. BK channel inhibition with IBTX leads to increased overall UBSM contractility (19, 40), resembling overactive bladder behavior. Studies from our laboratory have identified the BK channel as one of the most important K+ channels that controls membrane excitability in human UBSM (39). BK channel overexpression via gene transfer eliminates UBSM overactivity that is caused by experimental bladder outlet obstruction in rats (6), whereas the opposite phenomenon is observed in mice lacking functional BK channel subunits (32, 40). Plasmid-based BK channel α-subunit gene transfer for treatment of overactive bladder is now in clinical trials (30, 31).

Long-term bladder outlet obstruction leads to alteration in the β-AR densities or subtypes changing the bladder response to adrenergic stimuli (33). It may also be speculated that in overactive bladder there is a decrease in the inhibitory response to noradrenaline mediated by β3-ARs. RyRs expression is decreased in rat UBSM with experimental outlet obstruction (26). Data from RyR type 2 (RyR2) heterozygous mice (RyR2+/−) indicate that RyR2 deficiency changes UBSM membrane potential and excitation-contraction coupling via BK channel modulation (23). Therefore, changes in BK channel functional coupling among β3-ARs, RyR, or PKA may be implicated in overactive bladder etiology.

This study provides evidence that in rat UBSM, β3-ARs and BK channels are functionally coupled at the SR and RyRs level to mediate relaxation. Alterations in this functional coupling may be involved in the pathology of overactive bladder. The results also support the general concept that selective β3-AR agonists might be effective therapeutics to control urinary bladder function. Novel β3-AR selective agonists, such as GW427353, which can suppress spontaneous UBSM contractions in animal and human UBSM tissues are now emerging as potential drugs for treatment of overactive bladder (3, 21).

GRANTS

The work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-070909 (to G. V. Petkov).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Adrian Bonev (University of Vermont), Hristo Gagov (University of Sofia), and Mu-Yan Chen (University of South Carolina) for their critical evaluation of this study and Dr. Jennifer G. Schnellmann (Medical University of South Carolina) for improving the quality of the manuscript.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson KE, Arner A. Urinary bladder contraction and relaxation: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 84: 935–986, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson KE, Wein AJ. Pharmacology of the lower urinary tract: basis for current and future treatments of urinary incontinence. Pharmacol Rev 56: 581–631, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biers SM, Reynard JM, Brading AF. The effects of a new selective β3-adrenoceptor agonist (GW427353) on spontaneous activity and detrusor relaxation in human bladder. BJU Int 98: 1310–1314, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brading AF Spontaneous activity of lower urinary tract smooth muscles: correlation between ion channels and tissue function. J Physiol 570: 13–22, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown S, Cui X, Hristov K, Petkov G. Inhibitory mechanism of BRL37344, a specific β3-adrenoceptor agonist, on guinea pig and rat urinary bladder smooth muscle contractions: role of the BK channel. FASEB Experimental Biology, Washington, DC, 2007.

- 6.Christ GJ, Day NS, Day M, Santizo C, Zhao W, Sclafani T, Zinman J, Hsieh K, Venkateswarlu K, Valcic M, Melman A. Bladder injection of “naked” hSlo/pcDNA3 ameliorates detrusor hyperactivity in obstructed rats in vivo. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R1699–R1709, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christ GJ, Hodges S. Molecular mechanisms of detrusor and corporal myocyte contraction: identifying targets for pharmacotherapy of bladder and erectile dysfunction. Br J Pharmacol 147, Suppl 2: S41–S55, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clouse AK, Riedel E, Hieble JP, Westfall TD. The effects and selectivity of β-adrenoceptor agonists in rat myometrium and urinary bladder. Eur J Pharmacol 573: 184–189, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danila CI, Hamilton SL. Phosphorylation of ryanodine receptors. Biol Res 37: 521–525, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doheny HC, Lynch CM, Smith TJ, Morrison JJ. Functional coupling of β3-adrenoceptors and large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in human uterine myocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 5786–5796, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferro A β-Adrenoceptors and potassium channels. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 373: 183–185, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frazier EP, Mathy MJ, Peters SL, Michel MC. Does cyclic AMP mediate rat urinary bladder relaxation by isoproterenol? J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313: 260–267, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frazier EP, Schneider T, Michel MC. Effects of gender, age and hypertension on beta-adrenergic receptor function in rat urinary bladder. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 373: 300–309, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimura T, Tamura K, Tsutsumi T, Yamamoto T, Nakamura K, Koibuchi Y, Kobayashi M, Yamaguchi O. Expression and possible functional role of the β3-adrenoceptor in human and rat detrusor muscle. J Urol 161: 680–685, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillespie JI Noradrenaline inhibits autonomous activity in the isolated guinea pig bladder. BJU Int 93: 401–409, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch 391: 85–100, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashitani H, Brading AF, Suzuki H. Correlation between spontaneous electrical, calcium and mechanical activity in detrusor smooth muscle of the guinea-pig bladder. Br J Pharmacol 141: 183–193, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heppner TJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Ca2+-activated K+ channels regulate action potential repolarization in urinary bladder smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 273: C110–C117, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrera GM, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of urinary bladder smooth muscle contractions by ryanodine receptors and BK and SK channels. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279: R60–R68, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrera GM, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT. Voltage dependence of the coupling of Ca2+ sparks to BKCa channels in urinary bladder smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280: C481–C490, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hicks A, McCafferty GP, Riedel E, Aiyar N, Pullen M, Evans C, Luce TD, Coatney RW, Rivera GC, Westfall TD, Hieble JP. GW427353 (solabegron), a novel, selective β3-adrenergic receptor agonist, evokes bladder relaxation and increases micturition reflex threshold in the dog. J Pharmacol Ex Ther 323: 202–209, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horn R, Marty A. Muscarinic activation of ionic currents measured by a new whole-cell recording method. J Gen Physiol 92: 145–159, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hotta S, Morimura K, Ohya S, Muraki K, Takeshima H, Imaizumi Y. Ryanodine receptor type 2 deficiency changes excitation-contraction coupling and membrane potential in urinary bladder smooth muscle. J Physiol 582: 489–506, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Igawa Y, Yamazaki Y, Takeda H, Hayakawa K, Akahane M, Ajisawa Y, Yoneyama T, Nishizawa O, Andersson KE. Functional and molecular biological evidence for a possible β3-adrenoceptor in the human detrusor muscle. Br J Pharmacol 126: 819–825, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Igawa Y, Yamazaki Y, Takeda H, Kaidoh K, Akahane M, Ajisawa Y, Yoneyama T, Nishizawa O, Andersson KE. Relaxant effects of isoproterenol and selective β3-adrenoceptor agonists on normal, low compliant and hyperreflexic human bladders. J Urol 165: 240–244, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang HH, Song B, Lu GS, Wen QJ, Jin XY. Loss of ryanodine receptor calcium-release channel expression associated with overactive urinary bladder smooth muscle contractions in a detrusor instability model. BJU Int 96: 428–433, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi H, Adachi-Akahane S, Nagao T. Involvement of BK(Ca) channels in the relaxation of detrusor muscle via beta-adrenoceptors. Eur J Pharmacol 404: 231–238, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kubota Y, Nakahara T, Yunoki M, Mitani A, Maruko T, Sakamoto K, Ishii K. Inhibitory mechanism of BRL37344 on muscarinic receptor-mediated contractions of the rat urinary bladder smooth muscle. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 366: 198–203, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu G, Shi J, Yang L, Cao L, Park SM, Cui J, Marx SO. Assembly of a Ca2+-dependent BK channel signaling complex by binding to β2 adrenergic receptor. EMBO J 23: 2196–2205, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melman A Gene therapy for male erectile dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am 34: 619–630, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melman A, Bar-Chama N, McCullough A, Davies K, Christ G. Plasmid-based gene transfer for treatment of erectile dysfunction and overactive bladder: results of a phase I trial. Isr Med Assoc J 9: 143–146, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meredith AL, Thorneloe KS, Werner ME, Nelson MT, Aldrich RW. Overactive bladder and incontinence in the absence of the BK large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. J Biol Chem 279: 36746–36752, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore CK, Levendusky M, Longhurst PA. Relationship of mass of obstructed rat bladders and responsiveness to adrenergic stimulation. J Urol 168: 1621–1625, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morita T, Iizuka H, Iwata T, Kondo S. Function and distribution of β3-adrenoceptors in rat, rabbit and human urinary bladder and external urethral sphincter. J Smooth Muscle Res 36: 21–32, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakahira Y, Hashitani H, Fukuta H, Sasaki S, Kohri K, Suzuki H. Effects of isoproterenol on spontaneous excitations in detrusor smooth muscle cells of the guinea pig. J Urol 166: 335–340, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nara M, Dhulipala PD, Wang YX, Kotlikoff MI. Reconstitution of beta-adrenergic modulation of large conductance, calcium-activated potassium (maxi-K) channels in Xenopus oocytes. Identification of the camp-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation site. J Biol Chem 273: 14920–14924, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nomiya M, Yamaguchi O. A quantitative analysis of mRNA expression of alpha 1 and beta-adrenoceptor subtypes and their functional roles in human normal and obstructed bladders. J Urol 170: 649–653, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oshita M, Hiraoka Y, Watanabe Y. Characterization of beta-adrenoceptors in urinary bladder: comparison between rat and rabbit. Br J Pharmacol 122: 1720–1724, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petkov G, Cui X, Hristov K, Rovner E. Electrophysiological and pharmacological evidence for the presence of the large conductance voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels in human urinary bladder smooth muscle: Potential physiological role. In: FASEB Summer Research Conference, Ion Channel Regulation. Snowmass Village, CO, 2007.

- 40.Petkov GV, Bonev AD, Heppner TJ, Brenner R, Aldrich RW, Nelson MT. Beta 1-subunit of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel regulates contractile activity of mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle. J Physiol 537: 443–452, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petkov GV, Heppner TJ, Bonev AD, Herrera GM, Nelson MT. Low levels of K(ATP) channel activation decrease excitability and contractility of urinary bladder. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 280: R1427–R1433, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petkov GV, Nelson MT. Differential regulation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels by beta-adrenoceptors in guinea pig urinary bladder smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C1255–C1263, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seguchi H, Nishimura J, Zhou Y, Niiro N, Kumazawa J, Kanaide H. Expression of β3-adrenoceptors in rat detrusor smooth muscle. J Urol 159: 2197–2201, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeda M, Obara K, Mizusawa T, Tomita Y, Arai K, Tsutsui T, Hatano A, Takahashi K, Nomura S. Evidence for β3-adrenoceptor subtypes in relaxation of the human urinary bladder detrusor: analysis by molecular biological and pharmacological methods. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 288: 1367–1373, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka Y, Horinouchi T, Koike K. New insights into beta-adrenoceptors in smooth muscle: distribution of receptor subtypes and molecular mechanisms triggering muscle relaxation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 32: 503–514, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thorneloe KS, Nelson MT. Properties and molecular basis of the mouse urinary bladder voltage-gated K+ current. J Physiol 549: 65–74, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uchida H, Shishido K, Nomiya M, Yamaguchi O. Involvement of cyclic AMP-dependent and -independent mechanisms in the relaxation of rat detrusor muscle via beta-adrenoceptors. Eur J Pharmacol 518: 195–202, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamaguchi O, Chapple CR. Beta 3-adrenoceptors in urinary bladder. Neurourol Urodyn 26: 752–756, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]