Abstract

Ischemia-reperfusion injury is a common pathological occurrence causing tissue damage in heart attack and stroke. Entrapment of neutrophils in the vasculature during ischemic events has been implicated in this process. In this study, we examine the effects that lactacidosis and consequent reductions in intracellular pH (pHi) have on surface expression of adhesion molecules on neutrophils. When human neutrophils were exposed to pH 6 lactate, there was a marked decrease in surface L-selectin (CD62L) levels, and the decrease was significantly enhanced by inclusion of Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) inhibitor 5-(N,N-hexamethylene)amiloride (HMA). Similar effects were observed when pHi was reduced while maintaining normal extracellular pH, by using an NH4Cl prepulse followed by washes and incubation in pH 7.4 buffer containing NHE inhibitors [HMA, cariporide, or 5-(N,N-dimethyl)amiloride (DMA)]. The amount of L-selectin shedding induced by different concentrations of NH4Cl in the prepulse correlated with the level of intracellular acidification with an apparent pK of 6.3. In contrast, β2-integrin (CD11b and CD18) was only slightly upregulated in the low-pHi condition and was enhanced by NHE inhibition to a much lesser extent. L-selectin shedding was prevented by treating human neutrophils with inhibitors of extracellular metalloproteases (RO-31-9790 and KD-IX-73-4) or with inhibitors of intracellular signaling via p38 MAP kinase (SB-203580 and SB-239063), implying a transmembrane effect of pHi. Taken together, these data suggest that the ability of NHE inhibitors such as HMA to reduce ischemia-reperfusion injury may be related to the nearly complete removal of L-selectin from the neutrophil surface.

Keywords: integrins, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, ischemia-reperfusion, Na+/H+ exchanger inhibitors, lactate

tissue acidification occurs under certain pathophysiological conditions such as ischemia, when tissue oxygenation is adversely affected as a result of hypoperfusion caused by hemorrhagic shock or interruption of blood flow. Severe and prolonged tissue ischemia leads to intracellular and extracellular acidification due to lactate production as a result of anaerobic metabolism (15, 19); because of this, extracellular tissue pH (pHe) can fall to very low values, even around pH 6 (18, 22, 28, 47).

Neutrophils play a pivotal role in ischemia-reperfusion injury (11, 32, 33). Extracellular acidification with low pH bicarbonate buffer (53) or high concentrations of CO2 (45) activates neutrophils and increases the number of surface β2-integrin (CD18) molecules, which mediate firm adhesion to endothelial cells (7, 50). These conditions also enhance neutrophil responses induced by chemotactic factors like N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP), delay neutrophil apoptosis, and extend neutrophil lifespan (52). All these changes in neutrophil properties under extracellular acidic conditions could lead to inappropriate tissue inflammation and tissue damage. On the other hand, these same conditions can promote the shedding of L-selectin, and it has been proposed that this may serve as a protective mechanism against overrecruitment of neutrophils at sites of injury.

L-selectin shedding occurs via the action of membrane-anchored metalloprotease proteins belonging to the ADAM family (a disintegrin and metalloprotease). These are responsible for the shedding of the ectodomains of diverse membrane-anchored molecules such as growth factors, cytokines, and receptors, in addition to L-selectin [see Blobel (5) for a review]. The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades have been implicated as mediators in the regulated shedding of different membrane proteins (12, 14, 40). In particular, the p38 pathway has been shown to be involved in the resting release of transforming growth factor-α and in the regulated shedding of L-selectin (12, 14). Understanding more about how changes in pHe are connected to changes in adhesion molecule expression could lead to the identification of new strategies for mitigating ischemic injury.

A key regulatory pathway by which neutrophils respond to changes in environmental pH is the Na+/H+ exchange (NHE) mechanism, and a role for NHE-1 inhibitors in limiting neutrophil accumulation at sites of ischemic injury has been proposed (17). Observations that human neutrophils express mRNA for the NHE-1 but not for the NHE-2, 3, or 4 isoforms (13) indicate that the principal Na+/H+ exchanger in neutrophils is NHE-1. NHE inhibitors, especially NHE-1 inhibitors, such as cariporide, eniporide, and zoniporide, have been found to attenuate myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in various experimental models (2, 8, 29). Cariporide has been shown to reduce human leukocyte rolling and adhesion by approximately 35–45% in a rat ischemia-reperfusion model and has also been shown to increase L-selectin shedding in fMLP-activated leukocytes in vitro (39).

In the present study, we have used lactate and the NH4Cl prepulse method (48) to lower intracellular pH (pHi) and to examine how surface expression of molecules participating in the adhesion mechanisms of neutrophils are affected by altering pHi in the presence and absence of NHE inhibitors. We examine effects on L-selectin (CD62L), which mediates transient rolling adhesion (4, 25) and expression of Mac-1 (CD11b, CD18), a mediator of firm adhesion (9). We demonstrate that low pHi induces L-selectin shedding, that this is enhanced in the presence of lactate and NHE inhibitors, and that shedding is prevented by drugs that inhibit activation of metalloproteases and p38 MAP kinase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

1-Step Polymorphs was obtained from Accurate Chemical and Scientific (Westbury, NY). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated monoclonal anti-L-selectin (CD62L, DREG56-FITC), anti-CD11b (Bear1-FITC), anti-CD18 (7E4-FITC) and isotype (mouse anti-human IgG1) antibodies were purchased from Beckman/Coulter (Miami, FL). Polyclonal antibody against phosphorylated p38 MAPK was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Annexin V-FITC was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). BCECF-AM [2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5,6-carboxyfluorescein-acetoxymethyl ester] was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). KDIX-73-4 was obtained from Janet Williams (University of Virginia), and RO-31-9790 was a kind gift from Roche (Welwyn Garden City, UK). Cariporide mesilate was obtained from Aventis Pharma Deutschland (Frankfurt, Germany). All other chemicals, including salts, were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and were of the highest purity available.

Buffers

The composition of the buffers was as follows (in mM).

) Neutrophil isolation buffer (pH 7.4) (NIB): 146 NaCl, 5 KCl, 5.5 glucose, and 10 HEPES.

) Control buffer (pH 7.4): 127 NaCl, 4.2 KCl, 5 glucose, 10 HEPES, 10 mM MES, 1.1 CaCl2, and 0.9 MgCl2.

) Lactate buffer pH 7.4: 115 NaCl, 4.2 KCl, 5 glucose, 10 HEPES, 10 mM MES, 1.1 CaCl2, 0.9 MgCl2, and 20 Na-lactate.

) Lactate buffer pH 6.0 or 6.7: 107 NaCl, 4.2 KCl, 5 glucose, 10 HEPES, 10 mM MES, 1.1 CaCl2, 0.9 MgCl2, 20 Na-lactate.

) Ammonium chloride buffer (10, 20, and 30 mM, pH 7.4): 127 NaCl, 4.2 KCl, 5 glucose, 10 HEPES, 10 MES, 1.1 CaCl2, and 0.9 MgCl2 (NH4Cl− was added to control buffer on the day of experiment).

The osmolality of the buffers was adjusted to 290–310 mosmol/kgH2O (measured with a Wescor vapor pressure osmometer) by using NaCl, and the pH was adjusted to the desired values at room temperature with either HCl or NaOH (except for NH4Cl buffer).

Neutrophil Isolation

Blood samples were obtained, with informed consent, from apparently healthy donors by venipuncture, according to procedures approved by the Institutional Human Subjects Review Board. Neutrophils were isolated from heparinized human blood samples by single density gradient centrifugation using a 1-Step Polymorphs reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Whole blood and 1-Step Polymorphs media were brought to room temperature before use. Three milliliters of 1-Step Polymorphs reagent were placed in an 8-ml Falcon polystyrene round-bottom tube (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), 3.5 ml of undiluted heparinized whole blood was carefully layered on the reagent and centrifuged at room temperature for 40–50 min at 1,500 rpm (470 g) in a Sorvall RC5C Plus centrifuge (Kendro Laboratory Products, Newtown, CT). After centrifugation, there were two visible leukocyte bands in the neutrophil isolation medium (NIM), the upper one being mononuclear cells (MN) and the lower one neutrophils. The upper NIM fraction and the MN were aspirated and discarded. The neutrophil band was collected with a Pasteur pipette, restored to normal osmolality by the addition of an equal volume of NIB diluted (1:1) with distilled, deionized water, and then suspended in a total volume of 5.0 ml of NIB containing 0.1% BSA (Fraction V, γ-globulin-free, and low endotoxin). Neutrophils were washed three times in 5.0 ml NIB by centrifugation at room temperature for 10 min at 1,000 rpm (210 g). Before the last wash, a small portion (0.5 ml) of the neutrophil suspension was removed for counting. Contaminating erythrocytes were hypotonically lysed by a 10-fold dilution or the sample with a 1:6 dilution of PBS with distilled water. Neutrophils were exposed to hypotonicity for 30 s, after which an appropriate volume of 4× PBS was added to restore isotonicity. For flow cytometry, the neutrophil suspension did not undergo hypotonic lysis, since contaminating erythrocytes can be clearly differentiated in this procedure. For cell suspension pH experiments, BSA was added with the 4× PBS buffer to make the final BSA concentration 0.1%. Cell were then centrifuged and washed once in NIB.

L-Selectin (CD62L), Mac1 (CD11b), and CD18 Measurements

Surface L-selectin, Mac1, and CD18 were determined by flow cytometry. For experiments to determine the effects of pHe, cells (106/ml) were incubated in lactate (pH 7.4, pH 6.7, or pH 6.0), or control (pH 7.4) buffer for 30 min. In these experiments, cells were preincubated with or without NHE inhibitor [5-(N,N-hexamethylene)amiloride (HMA)] for 60 min at 37°C. For experiments with an NH4Cl prepulse to lower pHi, cells were preincubated with or without inhibitors (KDIX-73-4 or RO-31-9790) for 30 min at 37°C, washed two times at room temperature in control buffer, pH 7.4, with or without NHE and/or metalloprotease inhibitors, resuspended in the corresponding buffer, and returned to a 37°C water bath for an additional 30 min. All samples were placed on ice after the incubation.

All neutrophil samples were then washed once with ice-cold control buffer, pH 7.4, before being labeled with the monoclonal antibodies. Neutrophils (5 × 105/ml) were incubated with saturating concentrations (20 μl) of DREG56-FITC, Bear1-FITC, or 7E4-FITC antibodies for L-selectin, CD11b, or CD18 measurement, respectively. Cells were incubated for 45 min at 4°C on a rocking platform. Cells were then washed twice with ice-cold control buffer at 4°C. A third wash was done with BSA-free control buffer, and cells were resuspended and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. Cells were washed once with BSA-free control buffer, resuspended at 106 cells/ml, and analyzed on an Epics Elite ESP (Coulter, Miami, FL) or on FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) flow cytometer using 488-nm excitation. Typically, 104 cells were analyzed per sample. Gating to exclude red blood cells was done by virtue of the greater forward and side scatter of the neutrophils. Results are expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the cells counted (in arbitrary units) or as percentage of pH 7.4 control based on MFI. For L-selectin, the number of positive cells was determined by comparison of histograms with those obtained using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated isotype control antibody as described by Preece et al. (38).

pHi Measurement

Neutrophils (106/ml) were incubated in NIB with 2 μM BCECF for 30 min at 37°C, followed by 10-min incubation at room temperature. Cells were then washed once in NIB buffer by centrifugation at room temperature for 10 min at 1,000 rpm (210 g) and resuspended in control buffer and kept at room temperature. Before the fluorescence measurements, 4 × 106 cells were washed once in control buffer and resuspended in 2 ml of the buffer of study prewarmed to 37°C. Subsequently, the suspension was immediately transferred into a 1-cm quartz cuvette that was placed in a thermostat-regulated cuvette holder (37°C) in Photon Technology International (PTI, South Brunswick, NJ) Alpha-1 fluorescence system. Excitation wavelengths of 500 and 440 nm were obtained from an excitation monochromometer of the PTI fluorescence system. The emission passed through a filter cube containing a 515 nm dichroic mirror and a 535 ± 12 nm band-pass emission filter and was captured by a photomultiplier tube. Emission with 500 or 440 nm excitation were corrected for lamp power and recorded using Felix software (PTI). A ratio curve was obtained from the two excitation wavelengths (500/440) with background (unlabeled cells) subtracted. The midpoint from linear fitting the ratio data over a 100-s period was used together with a calibration curve to determine pHi at that time. No correction was made for extracellular BCECF; this was checked in one experiment and found to have a negligible effect on calculated pHi. For the later time points, the cells were washed once to remove extracellular BCECF just before the measurement of fluorescence.

Apoptosis Assay

Cell death under different experimental conditions was determined by measuring the percentages of human neutrophils that were positive to annexin V after 2-h treatment. Briefly, polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) were isolated and resuspended in control buffer (pH 7.4) or in sodium lactate buffer (pH 6.0, 6.7, or 7.4). For PMN in control buffer, two groups of cells were subjected to a 30-min pretreatment with 30 mM NH4Cl, as described in previous experiments. PMN were incubated for 2 h in the presence or absence of 10 μM HMA, the NHE inhibitor. After treatment, PMN were placed on ice, labeled with annexin V-FITC (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and then subjected to flow cytometry. PMN apoptosis was determined by calculating the fraction of annexin V-positive cells using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Data are three different experiments using blood samples from three different donors and are expressed as percentage of total population that were annexin V-positive.

p38 MAP Kinase Activation

Activation of p38 MAP kinase by intracellular acidosis was assayed by immunoblots. Human neutrophils were first subjected to NH4Cl prepulse for 30 min at 37°C 37°C and then washed once with control buffer, and incubated with control buffer (control) or with 10 μM HMA. To test p38 MAP kinase inhibitor, neutrophils were first exposed to NH4Cl prepulse for 30 min at 37°C and then were washed once with control buffer and incubated with 10 μM HMA ± 2 μM SB-203580 (SB-203580 was present throughout the experiment, 1 h at 37°C ). Total protein was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Protein was subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using a 12% gel. Blotted membranes were incubated with p38 MAPK polyclonal antibody against phosphorylated p38 MAPK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to determine the content of the activated p38 MAPK. The blots were then incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for 1.5 h. After blots were washed several times with TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, the fluorescence was developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence immune blot detection agent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The arbitrary units of density of each lane were scanned with a computer software program (Image).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SE (error bars in plots) for n experiments as indicated. Significance was assessed using a paired two-sample t-test to determine differences between control and treatment for L-selectin, Mac1, and pHi in neutrophil suspension measurements. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effect of Low pHe, Lactate, and NH4Cl on pHi

To assay the effects of pHi on adhesion molecules, we first determined the changes induced by low pHe, lactate, and NH4Cl on pHi. BCECF was use to monitor pHi in cells in cuvette at 37°C.

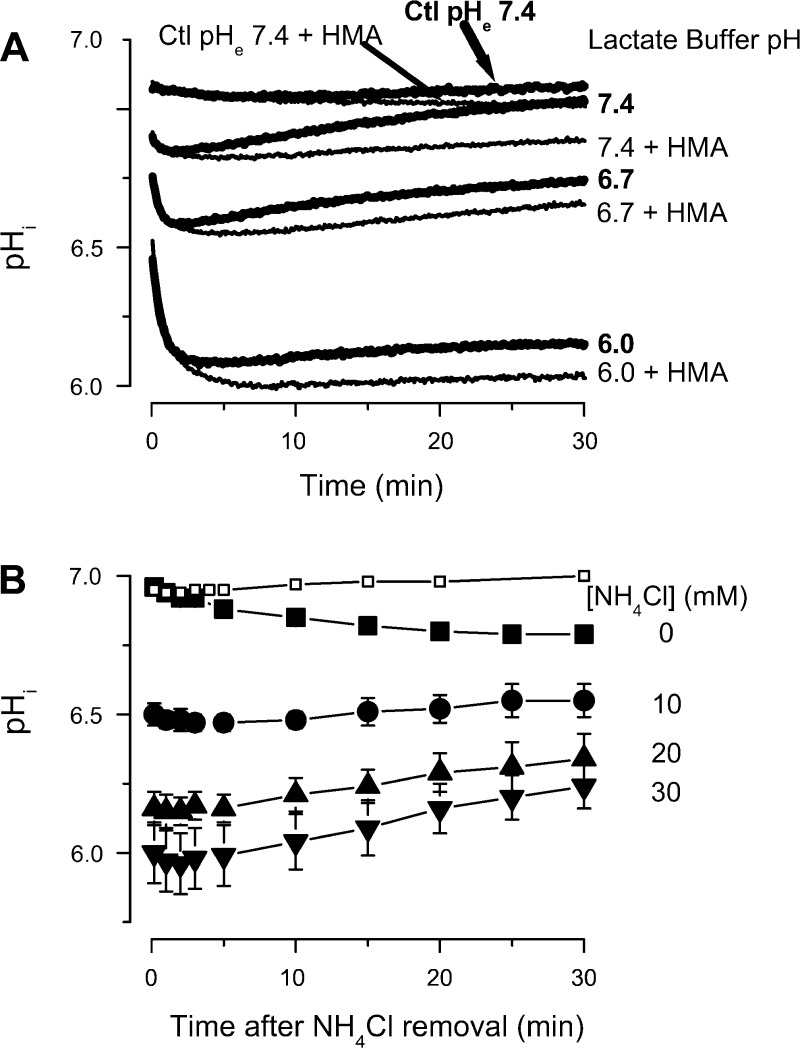

pHi measurement in lactate buffers.

When neutrophils were suspended in a pH 7.4 lactate (20 mM) solution, there was an initial decrease in pHi, which peaked at ∼2.5 min and then recovered to almost normal values by 30 min (Fig. 1A). In contrast, suspending neutrophils in pH 6.7 lactate or pH 6.0 lactate media caused a large decrease in pHi over at least a 30-min period, with little evidence of recovery. Control buffer at pH 7.4 (top thick line) or the same buffer containing 10 μM HMA (top thin line), a NHE inhibitor, without lactate had no effect (Fig. 1A). When 10 μM HMA was applied in lactate medium with pH 7.4, 6.7, or 6.0, the slight recovery of pHi was abolished and pHi remained acidic, without change during the entire 30-min observation (Fig. 1A). The transient effects of lactate on pHi are enhanced when the extracellular space is acidic, a finding in agreement with a previous study (49). These effects are only slightly enhanced by NHE inhibition.

Fig. 1.

Effect of extracellular lactate (20 mM) or low extracellular pH (pHe) on neutrophil intracellular pH (pHi). A: neutrophils were suspended in normal buffer pH 7.4 (Ctl) or with lactate buffers (pH 7.4, 6.7, 6.0) without (thick lines) or with (thin lines) 10 μM 5-(N,N-hexamethylene)amiloride (HMA). The graph is representative of at least 4 similar experiments. B: BCECF labeled neutrophils were exposed to solutions containing different concentrations of NH4Cl ([NH4Cl]), pH 7.4, for 30 min, then washed two times at room temperature (RT) with pH 7.4 control buffer + 10 μM HMA to thoroughly remove NH4Cl. Cells were resuspended in the same control buffer for measurement. □, control experiments obtained from cells preincubated in 30 mM NH4Cl, then washed two times at RT with pH 7.4 control buffer without HMA. The pHi was determined at the indicated times (n = 6).

The reduction in pHi that accompanies lactate acidosis was confirmed in a separate series of experiments. Simply incubating neutrophil suspensions in pH 6.0 lactate buffer for 15–25 min or 60–114 min caused a significant decrease (P < 0.01 vs. control) in pHi from 7.07 ± 0.01 to 6.31 ± 0.06 and 6.30 ± 0.05, respectively, without recovery to normal values, even after 114 min. When HMA was added to the pH 6.0 lactate buffer, incubating the neutrophil suspension for 15–25 min or 60–112 min caused a similar decrease in pHi to 6.34 ± 0.02 and 6.34 ± 0.04, respectively. Here again it appears that NHE inhibition does not appreciably augment the effect of reduced pHe on pHi.

pHi measurement in cells after NH4Cl prepulse.

In contrast, NHE inhibition did have a significant effect in prepulse experiments. Low values for pHi were reached and maintained when neutrophils were exposed to a 30 min NH4Cl, pH 7.4, prepulse (48) at 37°C followed by two washes at room temperature. Subsequent incubation for 30 min in pH 7.4 buffer at 37°C in the absence of NHE inhibition revealed little effect on pHi after prepulse and the two room temperature washing steps, indicating essentially full recovery of pHi during the washing steps. In contrast, in the presence of 10 μM HMA, a sustained intracellular acidification was observed (Fig. 1B). The magnitude of this acidification clearly depended on NH4Cl concentration. For example, with 10 or with 30 mM NH4Cl, the pHi at 15 min was 6.51 ± 0.51 and 6.09 ± 0.10, respectively. This made it possible to isolate the effects of pHi from pHe, because the cells could be maintained with low pHi for extended times after NH4Cl washout and the return to pH 7.4 buffer. Armed with these approaches, we proceeded to assess the effects of changing intracellular and extracellular pH on adhesion molecule expression.

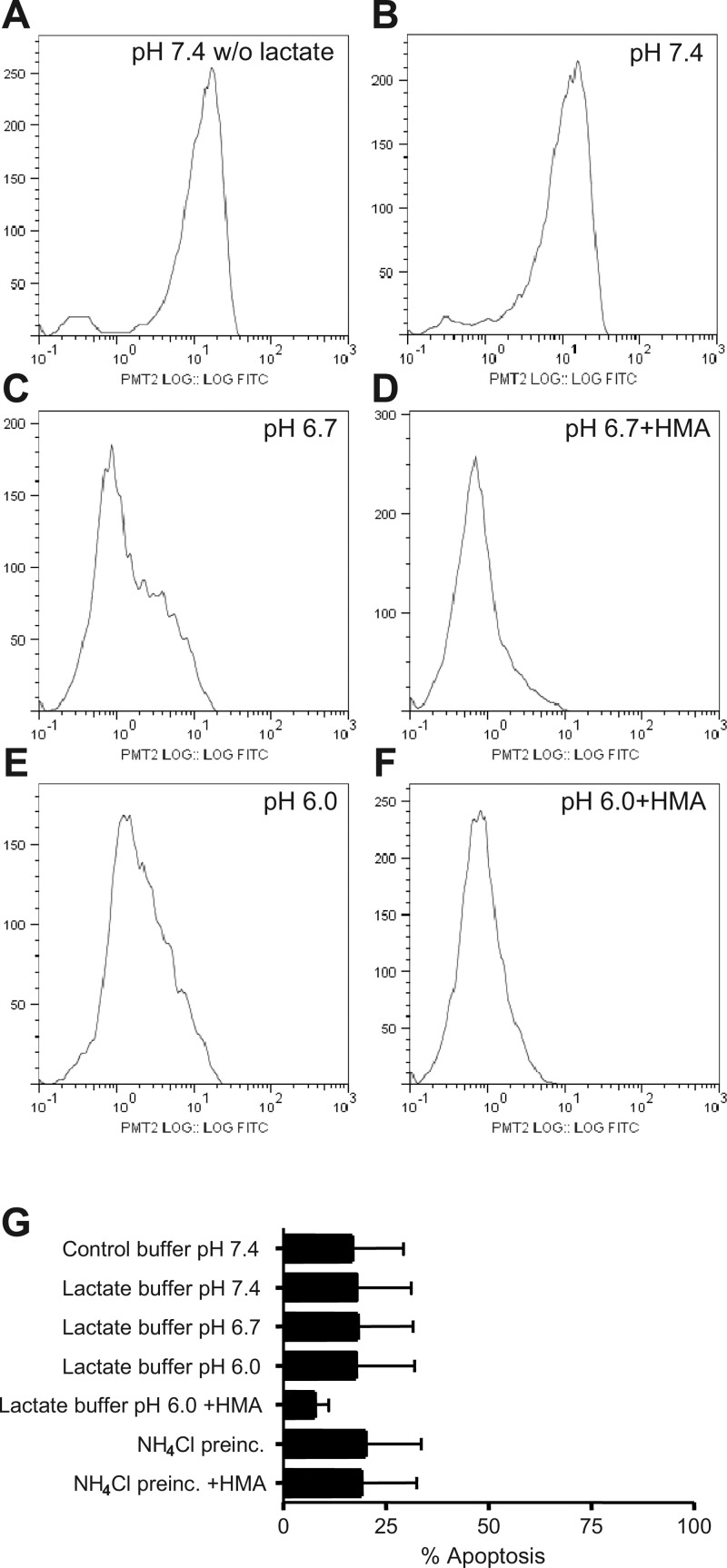

Effect of Low pHe and NHE Inhibitors on L-Selectin (CD62L) Level

Lactate buffers (20 mM) at different pH or NH4Cl prepulse were used to modify the pHi, and the effects on L-selectin expression were tested. Neutrophil L-selectin surface expression in lactate buffer at pH 7.4 was similar to cells in pH 7.4 control buffer without lactate (Fig. 2, A and B), but at pH 6.7, two population of cells were evident, one with markedly reduced L-selectin expression (Fig. 2C). This effect was enhanced by further reduction in pH or by NHE inhibition (Fig. 2, D–F). The differences between L-selectin levels at pH 6.7 and pH 7.4 were statistically significant (P < 0.01) as was the enhancement of L-selectin shedding by HMA (P < 0.01). The inhibitor HMA by itself had no effect on L-selectin expression (data not shown). This result contrasts somewhat with our observations that NHE inhibition did not significantly enhance the reduction in pHi brought about by incubation at low pH (Fig. 1A), raising the possibility that NHE may be protective of L-selectin shedding under low pH exposure, even though pHi is low. To determine whether or not the effects of intracellular acidosis were related to cell death, we determined cell viability by assessing the percentage of cells that were positive for annexin V after 2 h under acidic or control conditions. A summary of cell viability is shown in Fig. 2G. All experimental interventions (control pH 7.4, acid lactate, or NH4Cl ± HMA) do, in fact, induce an ∼18% of cells positive to annexin V, but treatment of cells at acidic pH caused no additional apoptosis. HMA slightly protected cells from death when intracellular acidification was induced with lactate pH 6.0 but not when induced by the NH4Cl prepulse. Thus, apoptosis cannot account for the changes in L-selectin expression that are observed under these different conditions.

Fig. 2.

Effect of extracellular lactacidosis on L-selectin shedding in human neutrophils. A and B: L-selectin shedding in control pH 7.4 without (A; w/o) or with (B) lactate. C and D: effect of 10 μM HMA in pH 6.7 lactate buffer. E and F: effect of 10 μM HMA in pH 6.0 lactate buffer. Graphs are flow cytometry data for 104 cells showing the distribution of FITC-labeled surface L-selectin molecules and are representative of 2–4 similar experiments. G: cell viability under different acidic conditions assessed as annexin V-positive polymorphonuclear neutrophils at 2 h. Data are means ± SE of at least 3 separate experiments for each point. *P < 0.05 vs. pH 7.4 lactate, **P < 0.03 vs. pH 7.4 lactate.

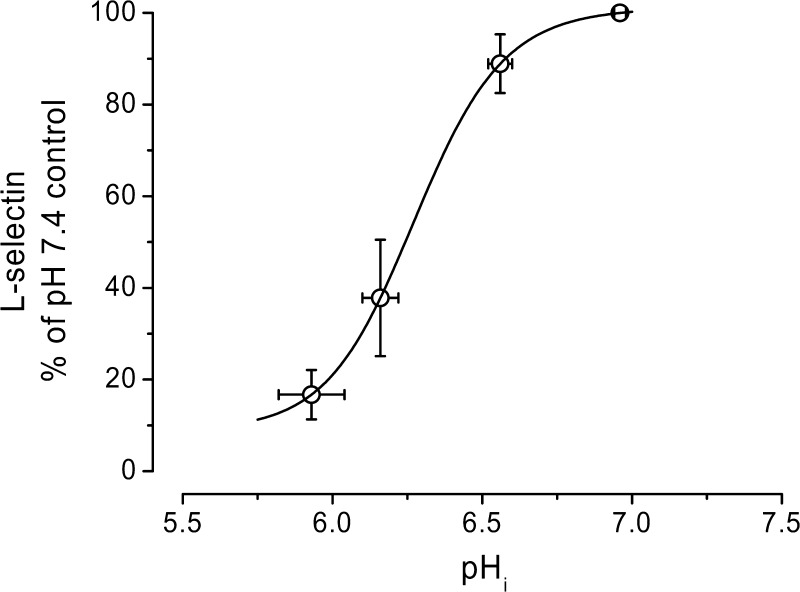

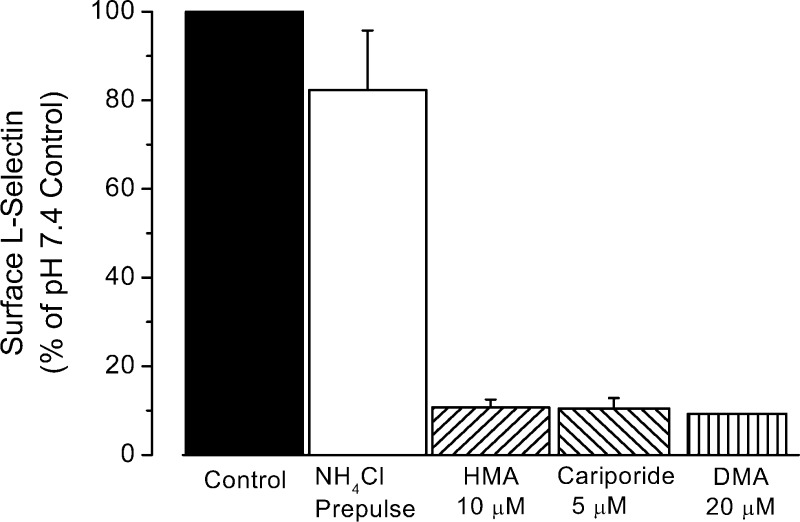

To further evaluate the role of pHi on L-selectin shedding, NH4Cl prepulse at different concentrations in the presence of HMA was used (as shown in Fig. 1B) to control pHi in a range of 6 to 7. The resulting alterations in L-selectin expression are shown in Fig. 3. As the pHi becomes acidic, the amount of L-selectin sharply decreases. A titration curve fit to the data indicates that the pK of this titration was roughly 6.3, well within the pH range observed during ischemic conditions (34, 51). As shown in Fig. 4, three different NHE blockers [10 μM HMA, 5 μM cariporide, and 20 μM 5-(N,N-dimethyl)amiloride (DMA)] produced similar results, decreasing L-selectin expression by ∼90%. [Note that cariporide is highly specific for the NHE-1 isoform, and both HMA and DMA are highly selective for NHE and weakly selective for the NHE-1 isoform (34).] When the NH4Cl prepulse was followed by washes and incubation in pH 7.4 buffer alone, L-selectin levels were decreased only slightly (82.3 ± 13.5% of the pH 7.4 control, P = 0.3), consistent with the more modest changes induced by this procedure on pHi (Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Effect of pHi on L-selectin shedding in human neutrophils. Different [NH4Cl] in the prepulse for 30 min at 37°C, followed by two washes at RT and a 30-min incubation at 37°C in control pH 7.4 + 10 μM HMA to inhibit the Na+/H+ exchanger, were used to lower the pHi (determined using BCECF), and the corresponding L-selectin surface expression was determined. Continuous line is the fit of a titration curve with a pK of 6.3.

Fig. 4.

Summary of effects of different Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) inhibitors on L-selectin shedding induced by a 30 mM NH4Cl prepulse. Cells were exposed to NH4Cl for 30 min at 37°C followed by two washes at RT and a 30-min incubation at 37°C in pH 7.4 control buffer with 10 μM HMA, 5 μM cariporide, or 20 μM 5-(N,N-dimethyl)amiloride (DMA). Control samples were either incubated for 30 min at 37°C, washed two times at RT and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in pH 7.4 control buffer (black column), or subjected to NH4Cl prepulse, washed two times with pH 7.4 control buffer and subsequent incubation in pH 7.4 buffer for 30 min (empty column). Thus ∼50 min elapsed from the beginning of the first wash after the prepulse to the placing of samples on ice for labeling. Number of experiments in each condition with duplicate samples was 14 (controls), 13 (HMA), 3 (cariporide), and 2 (DMA).

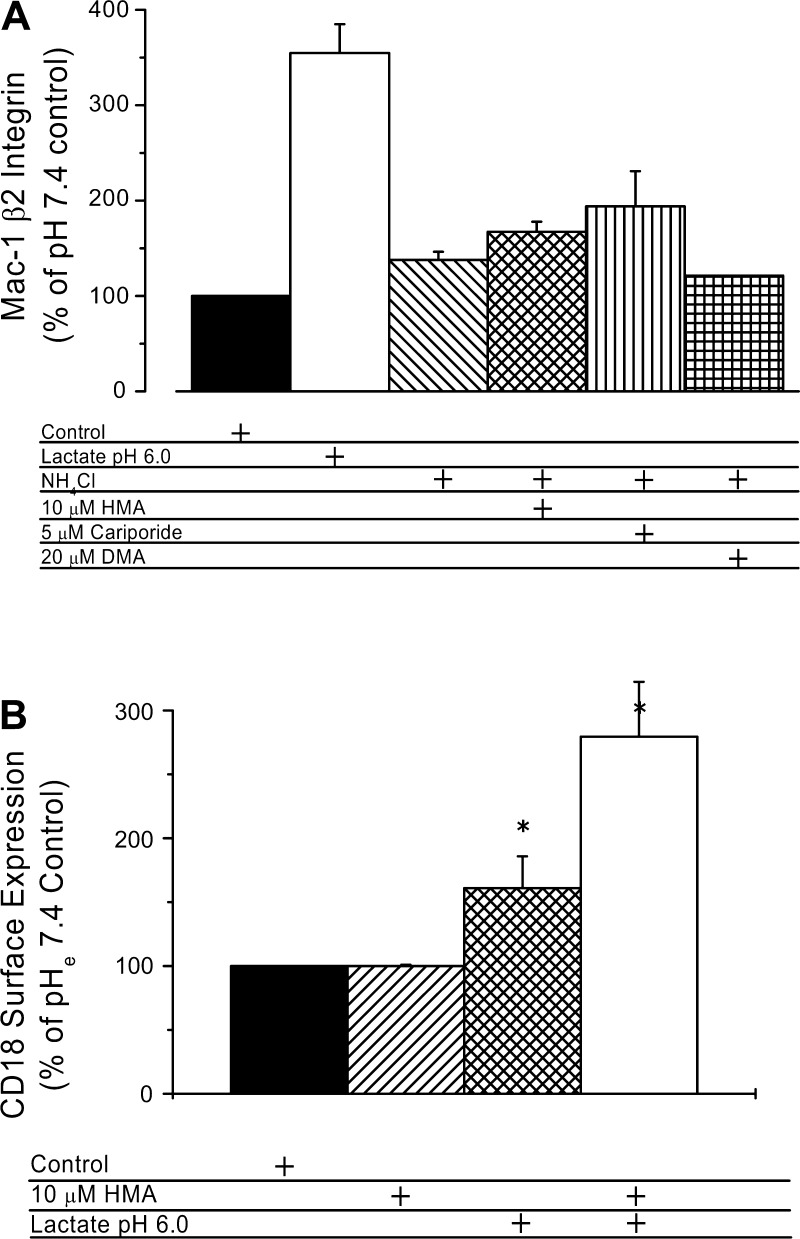

Effect of Low pH and NHE Inhibitors on Surface β2-Integrin (CD11b and CD18) Level

L-selectin and β2 integrins are both involved in neutrophil adhesion. As was shown above, L-selectin shedding is strongly regulated by pHi via a mechanism that involves NHE. To determine whether β2 integrin expression is also affected by intracellular acidification, we measured the effects of low pHi on Mac-1 (αM, CD11b) and CD18 (β2) surface expression using lactacidosis or NH4Cl prepulse with three different NHE inhibitors, HMA, cariporide, and DMA (Fig. 5). When neutrophils were exposed during 30 min to pH 6.0 lactate buffer, Mac-1 surface expression increased to 330% of control (Fig. 5A). In contrast, neutrophil exposure during 30 min to a 30 mM NH4Cl (pH 7.4) prepulse followed by an additional incubation in pH 7.4 buffer induced only a marginal increase in Mac-1 surface expression, and this was little enhanced by blocking NHE using 10 μM HMA, 5 μM cariporide, or 20 μM DMA (Fig. 5A). These increments induced by NHE inhibitors ranged from 120% to 190% of surface levels of Mac-1 in controls. In similar experiments (Fig. 5B), CD18 surface expression was enhanced to 161 ± 25% of control by exposure to lactate pHe 6.0. CD18 expression was further amplified to 280 ± 43% of control by the simultaneous exposure to lactate pHe 6.0 containing 10 μM HMA. These changes are comparable to the changes in Mac-1 expression after exposure to bacterial peptide (10 nM fMLP) (9).

Fig. 5.

Summary of effects of low pHi and of different NHE exchanger inhibitors on Mac-1 (CD11b) and CD18 induced by lactate pH 6 or by a 30 mM NH4Cl prepulse. A: effect of HMA, cariporide, and DMA on expression of CD11b. Control samples were handled as in Fig. 4. Approximately 50 min elapsed (20-min washing plus 30-min incubation) from the beginning of the first wash after the prepulse to the placing of samples on ice for labeling. Number of experiments with duplicate samples for each condition was 10 (HMA), 3 (cariporide), and 2 (DMA). Differences were not statistically significant except for the lactate pH 6.0 result. B: enhancement of CD18 surface expression by lactacidosis and HMA (number of experiments with duplicate samples for each condition was 3). *Statistically significant difference from control.

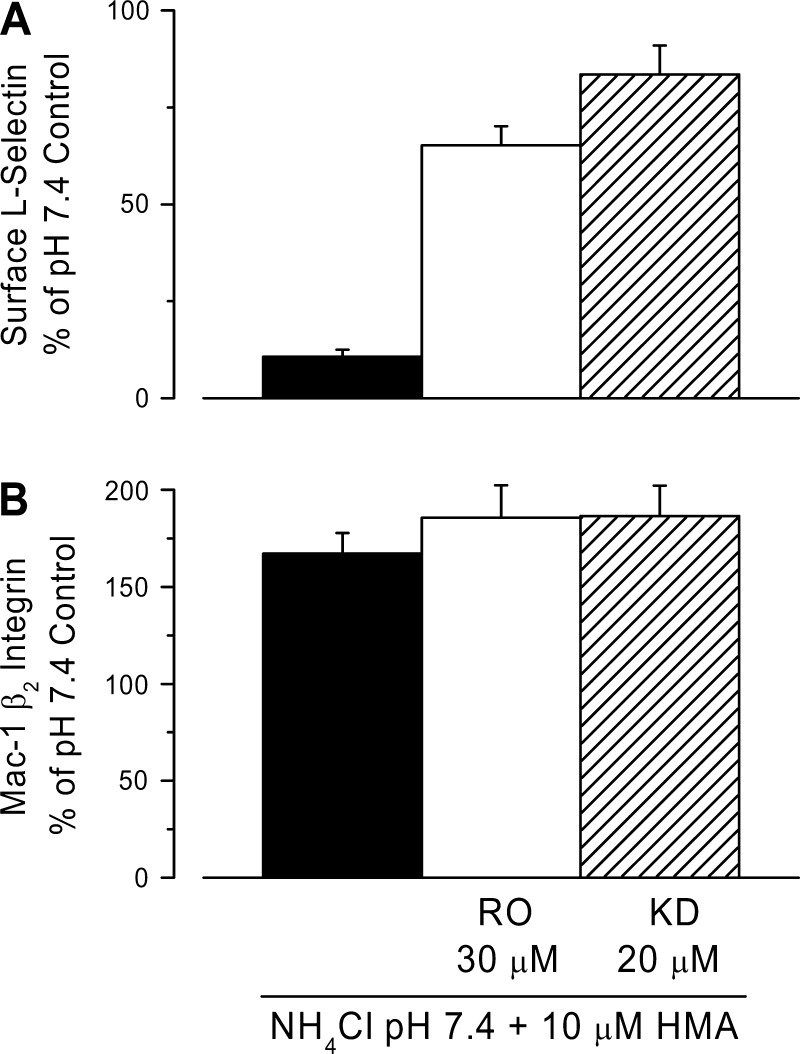

Role of Metalloprotease and p38 MAP Kinase in L-Selectin Shedding and β2-Integrin Surface Expression Induced by Low pHi

Metalloproteases and p38 MAP kinase have been implicated in shedding diverse membrane-anchored proteins including L-selectin (5). Two different metalloproteases inhibitors, RO-31-9790 (30 μM) and KD-IX-73-4 (20 μM) markedly reduced L-selectin shedding induced by a 30 mM NH4Cl prepulse followed by incubation in pH 7.4 buffer with 10 μM HMA (Fig. 6A). L-selectin levels were ∼65% of control with RO-31-9790, and 84% of control in the case of KD-IX-73-4. Neither of these drugs altered the effects of low pHi on Mac-1 β2-integrin (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Effects of metalloprotease inhibitors on L-selectin shedding (A) and β2-integrin (B) surface expression seen with low pHi. L-selectin shedding and β2-integrin surface expression were induced by a 30 mM NH4Cl prepulse for 30 min in the presence or absence of 30 μM RO-31-9790 (RO) or 20 μM KD-IX-73-4 (KD), followed by two washes at RT and a 30-min incubation in pH 7.4 control buffer + 10 μM HMA with or without each metalloprotease inhibitor. Control samples were handled as in Fig. 4. L-selectin data are for n = 13 experiments (control) and n = 3 experiments (inhibitors). β2-Integrin data are for n = 10 experiments (control) and n = 3 experiments (inhibitors) with duplicate samples in each experiment.

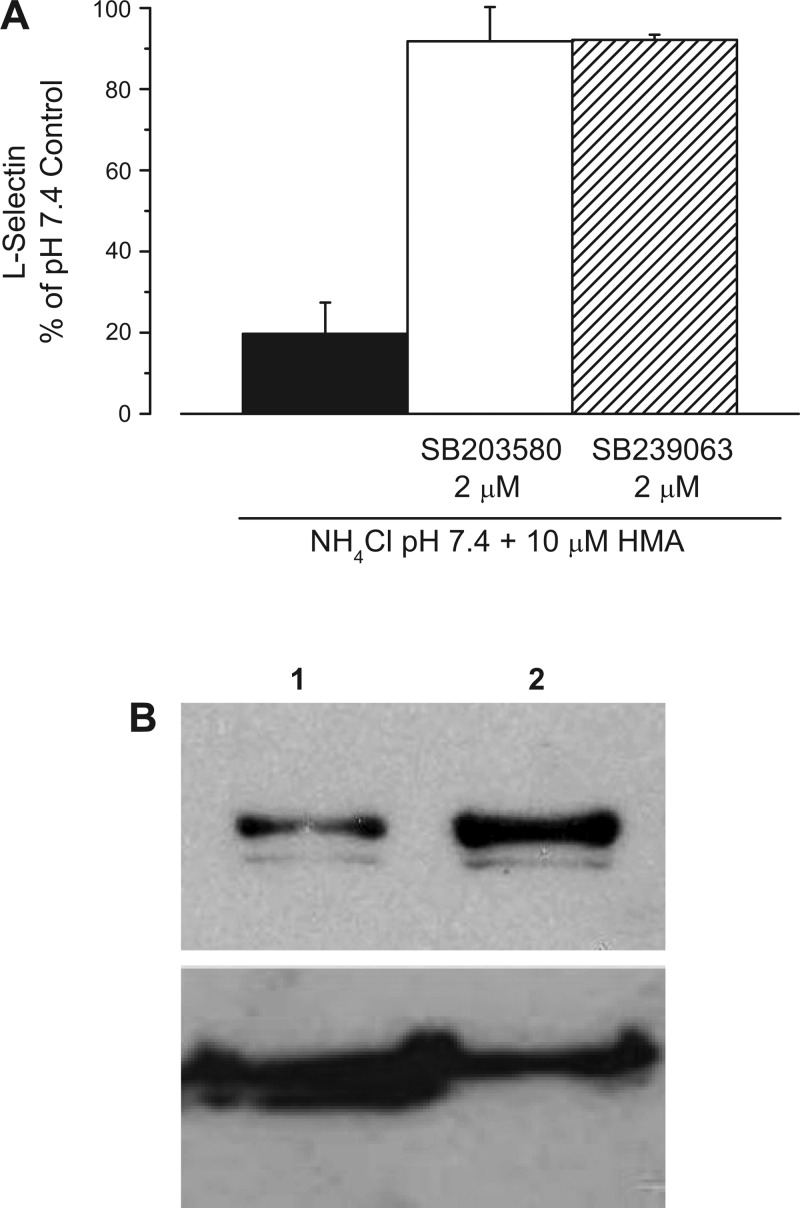

Signaling pathways involving p38 MAP kinase have been implicated in a variety of cases involving shedding of extracellular protein domains (12, 31, 40). To assess the possible participation of p38 MAP kinase in the cellular response to acidic pH, we tested the effects of two p38 MAP kinase inhibitors, SB-203580 and SB-239063. Either of these agents, at 2 μM concentration, fully prevented L-selectin shedding triggered by acidification of cytosol when human neutrophils were exposed to a 30 mM NH4Cl prepulse followed by incubation in pH 7.4 buffer with 10 μM HMA (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Effects of p38 MAP kinase inhibitors on L-selectin surface expression. A: human neutrophils were exposed to a 30 mM NH4Cl prepulse with or without 2 μM SB-203580 or 2 μM SB-239063, followed by two washes at RT and a 30-min incubation in pH 7.4 control buffer + 10 μM HMA with or without each p38 MAPK inhibitor. Control samples were handled as in Fig. 4. L-selectin levels were assessed on the basis of mean fluorescence intensity compared with the pH 7.4 control. Data are representative of n = 5 (SB-203580) and n = 3 (SB-239063) different experiments with duplicate samples in each experiment. B: intracellular acidification enhanced p38 MAP kinase activity. Top, Western blot using protein (24 μg in each lane) isolated from neutrophils subjected to NH4Cl prepulse (1, density = 21.9) or 10 μM HMA applied after the wash period (2, density = 55.7). Bottom, Western blot using protein (22.5 μg in each lane) isolated from neutrophils exposed to NH4Cl prepulse and then treated 10 μM HMA applied after the wash period (1, density = 74.3) or from neutrophils exposed to 2 μM SB-203580 during NH4Cl prepulse and then to 10 μM HMA ± 2 μM SB-203580 applied after the wash period (2, density = 46.1).

The above data suggest that p38 MAP kinase is activated by lactacidosis. To directly demonstrate this, we measured the phosphorylated form of p38 MAP kinase using a phosphospecific antibody. Figure 7B (top) shows a Western blot from neutrophils exposed to the NH4Cl prepulse then washed with control buffer (lane 1) and from cells exposed to NH4Cl prepulse then washed with buffer containing 10 μM HMA (lane 2). NH4Cl prepulse with 10 μM HMA induced an increase in the phosphorylated form of p38 MAP kinase to 220% of control (n = 5). As expected and as previously shown by others (30, 54, 55), neutrophils that were first treated with 2 μM SB-203580, a MAP kinase inhibitor, failed to increase the phosphorylated form of p38 MAP kinase. Figure 7B (bottom) shows a Western blot using protein isolated from neutrophils exposed to NH4Cl prepulse then washed with solution containing 10 μM HMA (lane 1) and from neutrophils treated with 2 μM SB-203580 during the NH4Cl prepulse then washed with solution containing 10 μM HMA and 2 μM SB-203580 (lane 2). In the presence of inhibitor, the phosphorylated p38 MAP kinase was 67% of that observed without inhibitor (n = 4). Thus, lactacidosis enhances p38 MAP kinase activity, which is associated with L-selectin shedding.

DISCUSSION

The preceding results demonstrate that lowering pHi induces shedding of L-selectin in neutrophils and causes an increase in Mac-1 expression. The L-selectin shedding and, to a lesser extent, the increase in Mac-1 expression, are enhanced by NHE inhibition. These effects occurred whether the decrease in pHi was brought about by incubation with lactate at low pH, or by pretreating the cells with NH4Cl and NHE inhibitors. The latter case further demonstrates that it is the reduction in intracellular, not extracellular, pH that causes the effect. The finding that L-selectin shedding is blocked by inhibition of either extracellular metalloproteases or intracellular signaling by p38 MAPK indicates that L-selectin shedding involves an inside-out process in which reduced pHi is transduced via p38 MAPK into cleavage of L-selectin by extracellular metalloproteases. Taken together, these data imply that sustained, highly acidic pHi, such as might occur in brain or cardiac tissues during an ischemic event, is sufficient to produce changes in neutrophil surface adhesion molecules similar to the changes seen on exposure to activators.

Role of Lactate

It is clear that the presence of lactate in the extracellular medium facilitates the drop in pHi. This is in keeping with other evidence that membrane permeability to H+ is limited, but that H+ transport can be facilitated by organic acids, suggesting the presence of cotransport mechanism of organic acid coupled to H+ as suggested earlier by Simchowitz and Textor (49). Grinstein et al. (16) note that the neutrophil response to being placed in buffers with pH 5.5 is slow (reaching pH 6.0 after 15 min), but that this is accelerated in the presence of succinate (reaching 5.5 after just 3 min). Furthermore, this intracellular acidification, but not normal pH 7.4, induces an inhibitory effect on the respiratory burst of neutrophils (43). Thus, succinate can act as a protonophore, shuttling H+ back and forth across the membrane. On the basis of this result and the strong pH dependence of lactate uptake, we surmise that lactate acts by a similar mechanism. Transport of lactate into the cell, however, does not in itself account for all the changes in adhesion molecule expression, as these occur when pHi is decreased by NH4Cl prepulse in the absence of lactate.

The relatively small effect that inhibition of NHE-1 had on lactate-facilitated pH reduction might be explained by a reduction in NHE-1 activity when the external pH falls below 7.4 (1). It appears that the influx of protons facilitated by lactate overwhelms the reduced capacity of NHE-1 at low pH, such that the net change in pH is only slightly affected upon NHE-1 inhibition.

Relation to Physiological Effects of NHE Inhibitors on Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

Several lines of evidence indicate that NHE plays a key role in myocardial injury induced by ischemia and reperfusion (10, 17, 34), and inhibitors of NHE have been tested clinically for their ability to alleviate ischemia-reperfusion injury. It is thought that NHE activation by acidic conditions enhances extrusion of H+ and influx of Na+ (10, 17, 26, 34). The consequent elevation of intracellular Na+ concentration can subsequently activate Ca2+ entry through the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, causing Ca2+ overload and cell damage (10, 34). High intracellular Ca2+ overload in ischemic reperfused tissue is thought to be one of the main reasons for injury. By interrupting this process at an early phase, NHE inhibition can prevent or delay the consequences of ischemia and reperfusion (44). In this case, the use of NHE inhibitors, such as cariporide and KR-32570, remains as a clear prospect for clinical application in preventing reperfusion injury (6) caused by Ca2+ overload. However, a recent result has raised some questions about this mechanism. Overexpression of NHE-1 in myocardial tissue does not further contribute to ischemia-reperfusion injury in the myocardium, but in fact alleviates postischemic injury (20). In a study of these overexpressing animals, cariporide provided equal protection against ischemic injury for both wild-type and NHE-overexpressing hearts (20). This result suggests that additional mechanisms other than just NHE inhibition in myocardial tissues contribute to injury protection by NHE inhibitors, as also suggested by the Guardian Study (52).

It is well known that neutrophils also play a pivotal role in ischemia-reperfusion injury (11, 33), and there are several studies indicating that adhesion molecules on the neutrophil, including L-selectin, are a key part of this process. For example, in reperfused rat skeletal muscle, leukocyte rolling and adhesion along the venular endothelium was significantly reduced when neutrophil L-selectin was blocked (32). In addition, it has been shown that L-selectin is necessary for leukocyte adhesion to the microvascular but not to the macrovascular endothelial cells of the human coronary system (57), and that reducing the number of circulating neutrophils reduces ischemic injury (41). Furthermore, there is evidence for a correlation between reduction of surface L-selectin and increasing numbers of peripheral blood neutrophils (53), implying that fewer neutrophils migrate out of the vasculature when surface L-selectin is low. Thus, reducing neutrophil adhesion via L-selectin is a likely mechanism for reducing ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Our data demonstrate that L-selectin shedding and β2-integrin upregulation can be induced by lactacidosis and that L-selectin shedding in particular is enhanced by inhibiting NHE. These changes are similar to those seen when neutrophils are exposed to activating stimuli (27). Previous studies have shown, however, that the inhibition of NHE with different inhibitors, including HMA, protected against microvascular deterioration and myocardial injury after reperfusion (17, 21, 26, 56). This seems the opposite of the effect expected if NHE inhibition mimics neutrophil activation. Activation of human neutrophils with fMLP, PMA, or opsonized zymosa (OpZ) induces PKC activation (52), which would recruit to the plasma membrane the NADPH oxidase components responsible for the respiratory burst and the subsequent superoxide production (46). These processes are accompanied by a transient intracellular acidification followed by a sustained alkalinization (16). The NADPH oxidase responsible for the respiratory burst is strictly dependent on pHi but insensitive to pHe (37). The optimum pHi for the NADPH oxidase was found near 7.5, whereas at low or high pHi the oxidase becomes inactive. Thus, under our experimental conditions simulating ischemia (pHi ∼6 by inhibiting Na+/H+ exchange with HMA or cariporide), it would be predicted that the oxidase activity should decrease to around 20% (37) and that little or no O2− will be produced until the pH returned to more physiological levels. This could explain why neutrophil adhesion plays an important part in this process. If oxidative damage only occurs at 6.5<pHi<8, then cells may be washed away from the tissue during reperfusion before damage occurs. One might expect that the upregulation of Mac-1 associated with low pH might contribute to retention of cells on the endothelium, but this would only apply to cells already trapped in the ischemic tissue. On the other hand, substantially greater numbers of neutrophils have the potential to be recruited from the flowing blood during reperfusion, and if these new cells were captured on the endothelium, a step that requires rolling interactions via selectins, substantially greater damage would be expected to ensue. Thus, our results support earlier contentions that NHE inhibitors could reduce ischemia-reperfusion damage by attenuating leukocyte-dependent inflammatory responses (24). Specifically, NHE inhibition (e.g., by cariporide) could reduce leukocyte rolling, and subsequent adhesion and extravasation, providing protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury by preventing further recruitment to reperfused tissue.

Cell Swelling Is Unlikely to Be Responsible for HMA-Induced L-Selectin Shedding

Extracellular acidification induced by lactic acid during ischemia leads to a profound intracellular acidosis. The activation of NHE due to a decrease in pHi should lead to a net uptake of NaCl and water (36), which would cause the neutrophils to swell. Neutrophils have been shown to swell due to NHE activation by the chemotactic agent fMLP (42). As reported previously by our group (23), neutrophil swelling leads to L-selectin shedding. Our results show a pH-dependent shedding of L-selectin and β2-integrin upregulation, and it might be hypothesized that this is related to the extent of NHE activation and the consequent swelling due to Na+ influx. Cell swelling has been observed in endothelial cells during hemorrhagic shock (35, 36) and during lactacidosis in vitro (3), and in both cases, cell swelling was inhibited by inhibiting NHE. In our study, however, NHE inhibition in an acidic medium did not inhibit but instead enhanced L-selectin shedding (Fig. 2D and Fig. 3) and upregulated β2-integrin expression (Fig. 5). These data strongly argue that cell swelling caused by NHE activation cannot be the primary cause for the change in surface adhesion molecules. This is further supported by preliminary observations that neutrophil swelling is marginal, ∼22% or 26%, when exposed to lactate 6.0 and lactate 6.0 + 10 μM HMA, respectively (unpublished observations).

Intracellular Signaling

A more likely mechanism for low pHi-induced L-selectin shedding involves the participation of intracellular signaling events as demonstrated by the p38 MAP kinase activity enhancement induced by intracellular acidification. This enzyme has been implicated in the regulated shedding of L-selectin (12, 14), and a more recent report implicates it in L-selectin shedding induced by mechanical loading (31). Indeed, our present results demonstrate that p38 MAPK is an important mediator of L-selectin shedding induced by intracellular acidification as well. In all cases, inhibition of extracellular metalloprotease causes substantial reductions in L-selectin shedding. This implies that there is likely to be a transmembrane effect of p38 MAPK on the conformation of L-selectin, making it susceptible to cleavage by endogenous external metalloproteases. How the change in pHi or mechanical loading causes p38 MAPK activation remains unknown.

Conclusion

Intracellular acidification and NHE inhibition cause an extensive loss of surface L-selectin, which is very likely to reduce neutrophil rolling adhesion and possibly inhibit L-selectin-associated signaling processes. This would lead to a decrease in firm adhesion and transmigration, especially during reperfusion. Such a mechanism would explain the reduced tissue damage after reperfusion because fewer neutrophils would adhere to the endothelium, migrate into the tissue, and cause damage. Our data thus support the view that a reduction in neutrophil adhesion accounts at least in part for the beneficial effects of NHE inhibition on ischemia-reperfusion injury, and suggest the possible utility of therapeutic strategies directed at reducing L-selectin adhesion to reduce neutrophil invasion of tissues during an ischemic event, and prevent tissue injury.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant P01-HL-18208.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Peter Keng, Tara Calcagni, and Michael Strong of the Flow Cytometry Facility for assistance.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson PS, Suhm MA, Nee J. Interaction of external H+ with the Na+-H+ exchanger in renal microvillus membrane vesicles. J Biol Chem 258: 6767–6771, 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayoub IM, Kolarova J, Yi Z, Trevedi A, Deshmukh H, Lubell DL, Franz MR, Maldonado FA, Gazmuri RJ. Sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibition during ventricular fibrillation: beneficial effects on ischemic contracture, action potential duration, reperfusion arrhythmias, myocardial function, and resuscitability. Circulation 107: 1804–1809, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behmanesh S, Kempski O. Mechanisms of endothelial cell swelling from lactacidosis studied in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H1512–H1517, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg EL, McEvoy LM, Berlin C, Bargatze RF, Butcher EC. L-selectin-mediated lymphocyte rolling on MAdCAM-1. Nature 366: 695–698, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blobel CP ADAMs: key components in EGFR signalling and development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 32–43, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buerke M, Rupprecht HJ, vom Dahl J, Terres W, Seyfarth M, Schultheiss HP, Richardt G, Sheehan FH, Drexler H. Sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibition: novel strategy to prevent myocardial injury following ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Cardiol 83: 19G–22G, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butcher EC Leukocyte-endothelial cell recognition: three (or more) steps to specificity and diversity. Cell 67: 1033–1036, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox CS, Sauer H, Allen SJ, Buja LM, Laine GA. Sodium/hydrogen-exchanger inhibition during cardioplegic arrest and cardiopulmonary bypass: an experimental study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 123: 959–966, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diamond MS, Springer TA. A subpopulation of Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) molecules mediates neutrophil adhesion to ICAM-1 and fibrinogen. J Cell Biol 120: 545–556, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doggrell SA, Hancox JC. Is timing everything? Therapeutic potential of modulators of cardiac Na+ transporters. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 12: 1123–1142, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engler RL, Dahlgren MD, Morris DD, Peterson MA, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Role of leukocytes in response to acute myocardial ischemia and reflow in dogs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 251: H314–H323, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan H, Derynck R. Ectodomain shedding of TGF-alpha and other transmembrane proteins is induced by receptor tyrosine kinase activation and MAP kinase signaling cascades. EMBO J 18: 6962–6972, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukushima T, Waddell TK, Grinstein S, Goss GG, Orlowski J, Downey GP. Na+/H+ exchange activity during phagocytosis in human neutrophils: role of Fcgamma receptors and tyrosine kinases. J Cell Biol 132: 1037–1052, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gechtman Z, Alonso JL, Raab G, Ingber DE, Klagsbrun M. The shedding of membrane-anchored heparin-binding epidermal-like growth factor is regulated by the Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade and by cell adhesion and spreading. J Biol Chem 274: 28828–28835, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gevers W Generation of protons by metabolic processes in heart cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 9: 867–874, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grinstein S, Furuya W, Rotstein OD. Intracellular pH regulation in neutrophils: properties and distribution of the Na+/H+ antiporter. Soc Gen Physiol Ser 43: 303–314, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gumina RJ, Auchampach J, Wang R, Buerger E, Eickmeier C, Moore J, Daemmgen J, Gross GJ. Na+/H+ exchange inhibition-induced cardioprotection in dogs: effects on neutrophils versus cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H1563–H1570, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heuser D, Guggenberger H. Ionic changes in brain ischaemia and alterations produced by drugs. Br J Anaesth 57: 23–33, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ichihara K, Haga N, Abiko Y. Is ischemia-induced pH decrease of dog myocardium respiratory or metabolic acidosis? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 246: H652–H657, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imahashi K, Mraiche F, Steenbergen C, Murphy E, Fliegel L. Overexpression of the Na+/H+ exchanger and ischemia-reperfusion injury in the myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H2237–H2247, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito Y, Imai S, Ui G, Nakano M, Imai K, Kamiyama H, Naganuma F, Matsui K, Ohashi N, Nagai R. A Na+-H+ exchange inhibitor (SM-20550) protects from microvascular deterioration and myocardial injury after reperfusion. Eur J Pharmacol 374: 355–366, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobus WE, Taylor GJ 4th, Hollis DP, Nunnally RL. Phosphorus nuclear magnetic resonance of perfused working rat hearts. Nature 265: 756–758, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaba NK, Knauf PA. Hypotonicity induces L-selectin shedding in human neutrophils. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1403–C1407, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaminski KA, Bonda TA, Korecki J, Musial WJ. Oxidative stress and neutrophil activation–the two keystones of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int J Cardiol 86: 41–59, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kansas GS Structure and function of L-selectin. APMIS 100: 287–293, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karmazyn M, Ray M, Haist JV. Comparative effects of Na+/H+ exchange inhibitors against cardiac injury produced by ischemia/reperfusion, hypoxia/reoxygenation, and the calcium paradox. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 21: 172–178, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kishimoto TK, Jutila MA, Berg EL, Butcher EC. Neutrophil Mac-1 and MEL-14 adhesion proteins inversely regulated by chemotactic factors. Science 245: 1238–1241, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitakaze M, Weisfeldt ML, Marban E. Acidosis during early reperfusion prevents myocardial stunning in perfused ferret hearts. J Clin Invest 82: 920–927, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knight DR, Smith AH, Flynn DM, MacAndrew JT, Ellery SS, Kong JX, Marala RB, Wester RT, Guzman-Perez A, Hill RJ, Magee WP, Tracey WR. A novel sodium-hydrogen exchanger isoform-1 inhibitor, zoniporide, reduces ischemic myocardial injury in vitro and in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 297: 254–259, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kutsuna H, Suzuki K, Kamata N, Kato T, Hato F, Mizuno K, Kobayashi H, Ishii M, Kitagawa S. Actin reorganization and morphological changes in human neutrophils stimulated by TNF, GM-CSF, and G-CSF: the role of MAP kinases. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C55–C64, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee D, Schultz JB, Knauf PA, King MR. Mechanical shedding of L-selectin from the neutrophil surface during rolling on sialyl Lewis x under flow. J Biol Chem 282: 4812–4820, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lozano DD, Kahl EA, Wong HP, Stephenson LL, Zamboni WA. L-selectin and leukocyte function in skeletal muscle reperfusion injury. Arch Surg 134: 1079–1081, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lucchesi BR, Werns SW, Fantone JC. The role of the neutrophil and free radicals in ischemic myocardial injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol 21: 1241–1251, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masereel B, Pochet L, Laeckmann D. An overview of inhibitors of Na+/H+ exchanger. Eur J Med Chem 38: 547–554, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazzoni MC, Borgstrom P, Intaglietta M, Arfors KE. Lumenal narrowing and endothelial cell swelling in skeletal muscle capillaries during hemorrhagic shock. Circ Shock 29: 27–39, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazzoni MC, Intaglietta M, Cragoe EJ Jr, Arfors KE. Amiloride-sensitive Na+ pathways in capillary endothelial cell swelling during hemorrhagic shock. J Appl Physiol 73: 1467–1473, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan D, Cherny VV, Murphy R, Katz BZ, DeCoursey TE. The pH dependence of NADPH oxidase in human eosinophils. J Physiol 569: 419–431, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Preece G, Murphy G, Ager A. Metalloproteinase-mediated regulation of L-selectin levels on leucocytes. J Biol Chem 271: 11634–11640, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Redlin M, Werner J, Habazettl H, Griethe W, Kuppe H, Pries AR. Cariporide (HOE 642) attenuates leukocyte activation in ischemia and reperfusion. Anesth Analg 93: 1472–1479, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizoli SB, Rotstein OD, Kapus A. Cell volume-dependent regulation of L-selectin shedding in neutrophils. A role for p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 274: 22072–22080, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romson JL, Hook BG, Kunkel SL, Abrams GD, Schork MA, Lucchesi BR. Reduction of the extent of ischemic myocardial injury by neutrophil depletion in the dog. Circulation 67: 1016–1023, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosengren S, Henson PM, Worthen GS. Migration-associated volume changes in neutrophils facilitate the migratory process in vitro. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 267: C1623–C1632, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rotstein OD, Nasmith PE, Grinstein S. The bacteroides by-product succinic acid inhibits neutrophil respiratory burst by reducing intracellular pH. Infect Immun 55: 864–870, 1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scholz W, Albus U. Na+/H+ exchange and its inhibition in cardiac ischemia and reperfusion. Basic Res Cardiol 88: 443–455, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Serrano CV, Fraticelli A, Paniccia R, Teti A, Noble B, Corda S, Faraggiana T, Ziegelstein RC, Zweier JL, Capogrossi MC. pH dependence of neutrophil-endothelial cell adhesion and adhesion molecule expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 271: C962–C970, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheppard FR, Moore EE, McLaughlin N, Kelher M, Johnson JL, Silliman CC. Clinically relevant osmolar stress inhibits priming-induced PMN NADPH oxidase subunit translocation. J Trauma 58: 752–757, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siesjo BK Acid-base homeostasis in the brain: physiology, chemistry, and neurochemical pathology. Prog Brain Res 63: 121–154, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simchowitz L, Roos A. Regulation of intracellular pH in human neutrophils. J Gen Physiol 85: 443–470, 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simchowitz L, Textor JA. Lactic acid secretion by human neutrophils. Evidence for an H+ + lactate− cotransport system. J Gen Physiol 100: 341–367, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Springer TA Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature 346: 425–434, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ten Hove M, Nederhoff MG, Van Echteld CJ. Relative contributions of Na+/H+ exchange and Na+/HCO3− cotransport to ischemic Nai+ overload in isolated rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H287–H292, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Theroux P, Chaitman BR, Danchin N, Erhardt L, Meinertz T, Schroeder JS, Tognoni G, White HD, Willerson JT, Jessel A. Inhibition of the sodium-hydrogen exchanger with cariporide to prevent myocardial infarction in high-risk ischemic situations. Main results of the GUARDIAN trial Guard during ischemia against necrosis (GUARDIAN) Investigators. Circulation 102: 3032–3038, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trevani AS, Andonegui G, Giordano M, Lopez DH, Gamberale R, Minucci F, Geffner JR. Extracellular acidification induces human neutrophil activation. J Immunol 162: 4849–4857, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Warny M, Keates AC, Keates S, Castagliuolo I, Zacks JK, Aboudola S, Qamar A, Pothoulakis C, LaMont JT, Kelly CP. p38 MAP kinase activation by Clostridium difficile toxin A mediates monocyte necrosis, IL-8 production, and enteritis. J Clin Invest 105: 1147–1156, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu D, Cederbaum A. Glutathione depletion in CYP2E1-expressing liver cells induces toxicity due to the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and reduction of nuclear factor-kappaB DNA binding activity. Mol Pharmacol 66: 749–760, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamada K, Sasabe M, Matsui K, Yamamoto S, Ohashi N. Effects of SM-20550, a new Na+/H+ exchange inhibitor, on survival and infarct size in rat myocardial infarction. Pharmacology 64: 176–181, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zakrzewicz A, Grafe M, Terbeek D, Bongrazio M, Auch-Schwelk W, Walzog B, Graf K, Fleck E, Ley K, Gaehtgens P. L-selectin-dependent leukocyte adhesion to microvascular but not to macrovascular endothelial cells of the human coronary system. Blood 89: 3228–3235, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]