Abstract

The relationship between inborn maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) and skeletal muscle gene expression is unknown. Since low VO2max is a strong predictor of cardiovascular mortality, genes related to low VO2max might also be involved in cardiovascular disease. To establish the relationship between inborn VO2max and gene expression, we performed microarray analysis of the soleus muscle of rats artificially selected for high- and low running capacity (HCR and LCR, respectively). In LCR, a low VO2max was accompanied by aggregation of cardiovascular risk factors similar to the metabolic syndrome. Although sedentary HCR were able to maintain a 120% higher running speed at VO2max than sedentary LCR, only three transcripts were differentially expressed (FDR ≤ 0.05) between the groups. Sedentary LCR expressed high levels of a transcript with strong homology to human leucyl-transfer RNA synthetase, of whose overexpression has been associated with a mutation linked to mitochondrial dysfunction. Moreover, we studied exercise-induced alterations in soleus gene expression, since accumulating evidence indicates that long-term endurance training has beneficial effects on the metabolic syndrome. In terms of gene expression, the response to exercise training was more pronounced in HCR than LCR. HCR upregulated several genes associated with lipid metabolism and fatty acid elongation, whereas LCR upregulated only one transcript after exercise training. The results indicate only minor differences in soleus muscle gene expression between sedentary HCR and LCR. However, the inborn level of fitness seems to influence the transcriptional adaption to exercise, as more genes were upregulated after exercise training in HCR than LCR.

Keywords: microarray analysis, gene ontology, metabolic syndrome, MELAS, soleus muscle

low maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) has a strong link to cardiovascular disease (CVD) in both men and women (22, 30). Hence, the ability to utilize and deliver oxygen (O2) during exercise seems to represent a point of divergence for future health (15). Identifying mechanisms underlying low VO2max may also identify causes of susceptibility to CVD, and suggest molecular targets for prevention and treatment.

In the last several decades, physical inactivity accompanying modern lifestyle has impaired skeletal muscle contractile and metabolic functions, contributing to the current epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. The metabolic syndrome is defined as a cluster of cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, dyslipidemia, impaired glycemic control, and abdominal obesity (26), and serves as a more powerful predictor of premature CVD death than each separate factor alone (12).

Exercise training has beneficial effects on the metabolic syndrome through adaptations in skeletal muscle. Skeletal muscle tissue represents about half of the body mass and plays a fundamental role in whole body metabolism. Exercise-induced adaptations include e.g., increased expression of mitochondrial enzymes regulating fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) and increased skeletal muscle oxidative phosphorylation capacity (17, 27). The exact mechanisms by which these metabolic changes are connected to improved health, however, have not been resolved.

To study extremities in inborn VO2max and genetic contribution to the development of CVD, rats were artificially selected for running capacity over several generations to generate strains with genetically determined high or low VO2max (24). In this rat model, genes responsible for aerobic fitness are concentrated, while environmental components are minimized by maintaining a standardized environment. This makes these strains of substantial value for determining the genes causative of variation in VO2max. Moreover, as almost all human genes known to be associated with disease have orthologs in the rat genome, the rat is a highly applicable model system for questions regarding gene expression in humans (10).

In the present study, generation 16 of the strains of high capacity runners (HCR) and low capacity runners (LCR) had an inborn 30% difference in VO2max (20). Interestingly, throughout the generations LCR accumulated risk factors of CVD, such as hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance, visceral adiposity, hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and elevated plasma free fatty acids; commonly diagnosed as the metabolic syndrome (20, 43). This makes this model of substantial value for studying the genetic background for the development of metabolic dysfunction. Gene expression profiling of the left ventricle from HCR and LCR revealed several differences that partly account for the divergence between the strains and the development of the metabolic syndrome in LCR (4), but the gene expression profiles of sedentary and exercise-trained rats from this model has not yet been determined in skeletal muscle. For that reason, we tested the hypothesis that selection for different inborn levels of VO2max results in differential gene expression patterns in the soleus muscle, and examined whether different levels of inborn VO2max affects transcriptional adaptation to exercise training.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

We used rats artificial selected for high and low VO2max, starting from the N: NIH stock obtained from the National Institutes of Health (USA). The model is described elsewhere (24, 43). Briefly, the rats in each generation were tested for exercise capacity by treadmill running at 11 wk of age. The individuals with the highest and lowest running capacity were selected and each group served as the mating population for the next generation. Female rats from generation 16 were used in this study. The study includes four groups; exercise-trained LCR (LCR-T) (n = 4), sedentary LCR (LCR-S) (n = 4), exercise-trained HCR (HCR-T) (n = 4) and sedentary HCR (HCR-S) (n = 4). Experimental protocols were approved by the respective Institutional Animal Research Ethics Councils.

Exercise training.

We trained the rats by an aerobic interval training program previously described (20, 41). Briefly, after 10 min of warm-up, rats ran uphill (25°) on a treadmill for 1.5 h, alternating between 8 min at an exercise intensity corresponding to 85–90% of VO2max and 2 min active recovery at 50–60%. Exercise was performed 5 days per week over 8 wk; controls were age-matched rats that remained sedentary. We measured VO2max every week to adjust speed to maintain the intended relative intensity throughout the experimental period. The VO2max test protocol consisted of 20 min warm-up at 50–60% of VO2max, whereupon treadmill velocity was increased by 0.03 m/s every 2 min until VO2 plateaued despite increased workload. The animals in the sedentary groups were treated similarly to the exercise groups, except they were not exposed to exercise training and the VO2max tests during the exercise period.

Tissue collection.

At ∼7 mo of age, and 48 h after the last exercise session, all the animals were killed. One of the soleus muscles was formalin fixated for immunohistochemistry and morphological studies, whereas the other was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for later genetic screening and protein analysis.

Total RNA isolation.

Tissue samples (20 mg) were homogenized in 100 μl TRIzol (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) using a Mixer Mill MM301 (Geneq, Montreal, Canada) at 20–25 Hz. RNA was further isolated and cleaned using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA integrity, purity and quantity were assessed by Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and Nanodrop (NanoDrop Technologies, Baltimore, MD). There were no significant differences in total RNA quantity obtained from the samples from the different groups.

Processing of Affymetrix data.

High quality RNA classified with a RNA integrity number value >7 and 260/280 ratio >1.8 was used for the microarray experiments. We used 5 μg total RNA from each sample for cDNA synthesis and further analysis. Labeled cRNA was prepared and hybridized to the RAE 230 2.0 chip from Affymetrix GeneChip (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) comprising 31,042 probe sets.

Statistical analysis for finding differentially expressed genes.

The summary measure for each probe set was background-corrected, quantile-normalized and log-transformed by use of the robust multiarray average (RMA) method (21). For each gene (probe set), a linear regression model, including parameters representing the effect of running capacity, is specified. Tests for significant differential expression between the groups were performed using moderated t-tests (37). To account for multiple testing, we calculated adjusted p-values controlling the false discovery rate (FDR), with the use of the Benjamini-Hochberg step-up procedure (3). All statistical analyses on the gene expression data were performed using the R language (R Development Core Team, 2004) and packages affy, affyPLM, and limma from the Bioconductor project (9).

Database submission.

The microarray data were prepared according to the “minimum information about microarray experiment” (MIAME) recommendations, and deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with accession number GSE10527.

Functional clustering according to gene ontology (GO) annotations.

To obtain information about gene/protein function, we used GeneTools (eGOn) (www.genetools.no) described previously (1). Lists of differentially expressed genes (FDR ≤ 0.05) were submitted to eGOn, which automatically associates gene ontology terms from Entrez Gene to the submitted gene reporters. The annotations used were based on UniGene build no. 157 (November 2006) at the time of the analysis. In addition, we used the NetAffx Analysis Center to correlate the microarray results with gene and annotation information (www.affymetrix.com).

In eGOn, Fisher's exact test assessed the relative numbers of GO annotations linked to differentially expressed genes, compared with the relative numbers of the same GO annotations linked to all the genes on the microarray. In a master-target situation the GO categories of the differentially expressed genes (target list) are compared with the distribution of GO categories for all gene reporters represented as physical probes on the microarray (master list). The purpose is to find whether, in any of the GO categories, the genes of interest are over- or underrepresented compared with the genes represented on the microarray. In addition, the differentially expressed genes were analyzed by the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis Application Tool (www.ingenuity.com) for pathway analysis.

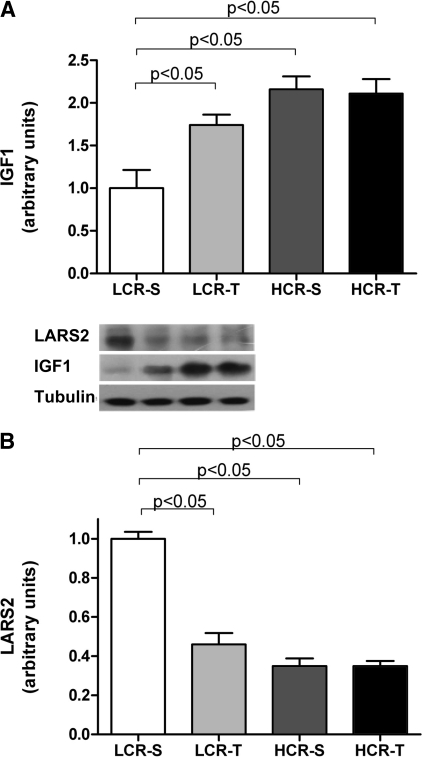

Western analysis.

Soleus protein levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and leucyl-transfer RNA synthetase 2 (LARS2) were measured to confirm the gene expression data. Homogenized samples (n = 4 per group) were loaded onto a 4–12% or 10–20% NuPAGE Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), separated by electrophoresis, and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membranes were incubated with LARS2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and IGF1 (Abcam) primary antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugate secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Rockford, IL) were used for protein detection with GBOX/Chemi-HR16E (Synoptics, Cambridge, UK). All protein levels were normalized to total tubulin (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) and quantified using ImageJ software (NIH Image, Bethesda, MD).

Fiber typing.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded soleus muscle sections (4 μm) were prepared by a standard immunohistochemistry protocol. Anti-fast skeletal myosin (Abcam) were used to detect the relative number of fast twitch fibers in the soleus muscle of all groups (n = 4 per group). Results were visualized by Envision + TM detection system (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). The degree of positive-staining was determined by semi-quantitative microscopy.

Statistics for protein levels.

To analyze differences in running speed between all groups before and after the exercise intervention we applied one-way analysis of variance, with Scheffé's post hoc test. To analyze statistical differences in fiber type distribution and in protein levels between groups we applied the Mann-Whitney test in SPSS v. 14.0. Data are presented as means ± SD, and only P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Physiological data.

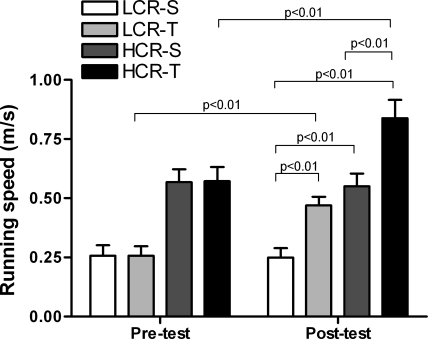

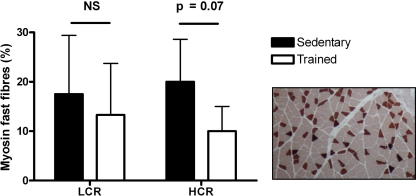

Previous studies of this animal model reported that LCR were born with a predisposition for CVD, as they were insulin-resistant, hyperglycemic, hyperlipidemic, obese, hypertensive, and had vascular and cardiac dysfunction (43). Høydal et al. (20) have previously reported that the LCR-S and HCR-S differed significantly in VO2max and that both groups improved their VO2max after 8 wk of exercise training (Table 1). HCR also maintained a significantly higher running speed at VO2max than LCR, when both sedentary and exercise-trained animals are compared (Fig. 1). The exercise training significantly increased running speed in both HCR and LCR (Fig. 1). Consistent with a low tolerance for exercise, LCR-S had 17% higher O2 cost of running compared with HCR-S at generation 11 (43). Fiber-type distribution was similar in HCR-S and LCR-S, but after exercise training we found a strong trend (P = 0.07) toward fewer fast fibers in the HCR group (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

VO2max of LCR and HCR, separated in groups of sedentary controls and exercise-trained, as previously reported by Høydal et al. (20)

| LCR-S | HCR-S | LCR-T | HCR-T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VO2max, ml·kg−0.75·min−1 | 39.1±2.3 | 50.6±4.2* | 38.8±2.2 | 50.9±3.9 |

| Pretest values | ||||

| VO2max, ml·kg−0.75·min−1 | 38.0±2.3 | 49.6±4.3* | 57.0±4.6† | 70.4±4.1‡ |

| End-point values |

LCR-S and HCR-S differed significantly (P < 0.01).

LCR-T had significantly improved function compared with LCR-S (P < 0.01).

HCR-T had improved function compared with HCR-S (P < 0.01). VO2max, maximal oxygen uptake; LCR-S, sedentary low capacity runners; HCR-S, sedentary high capacity runners; LCR-T, exercise-trained low capacity runners; HCR-T, exercise-trained high capacity runners.

Fig. 1.

Running speed (m/s) at maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) before and after the exercise period. LCR-S, sedentary low capacity runners; HCR-S, sedentary high capacity runners; LCR-T, exercise-trained low capacity runners; HCR-T, exercise-trained high capacity runners.

Fig. 2.

Staining of myosin fast fibers in soleus muscle cross sections. An example of myosin fast staining (dark fields) of a sedentary HCR is included. LCR, low capacity runners; HCR, high capacity runners; NS, not significant.

Gene expression data.

Of ∼28000 screened transcripts, three were differentially expressed (FDR P ≤ 0.05) in the soleus muscle between the sedentary HCR and LCR. One of these transcripts (1373602_at) was of special interest, because sequence alignment and homology analysis indicated strong homology to LARS2 in humans. This transcript was 65% more abundant in LCR-S than HCR-S. After exercise training, 58 transcripts were altered in the soleus muscle of HCR (Table 2), in contrast to only one in the LCR group. A transcript (1374698_at) similar to the cytochrome c oxidase (Cox) VIIa, a subunit of complex IV, was upregulated after exercise training in both groups. In the LCR group, this transcript level was 3.19-times higher after exercise training, whereas a four times higher expression was detected in HCR. The adaptation to exercise training in HCR affected genes involved in fatty acid metabolism [e.g., carnitine o-octanoyltransferase (Crot) and enoyl CoA hydratase (Auh)], in addition to genes located in the peroxisomes (Table 3). In addition, the Ingenuity pathway tool reported that the adaptation to exercise in the soleus muscle of HCR was associated with increased fatty acid elongation in the mitochondria [e.g., peroxisomal trans-2-enoyl-CoA reductase (Pecr)] (Table 4). Of particular interest, myosin heavy chain 4 (Myh4) appeared upregulated in HCR after exercise training (Table 2).

Table 2.

Transcripts significantly up- and downregulated following exercise training in HCR that were associated with a transcript name

| Identifier | UniGene ID | Symbol | Transcript Name | Ratio HCR-T/HCR-S | FDR Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1370900_at | Rn.10092 | Myh4 | myosin, heavy chain 4, skeletal muscle | 33.95 | 0.05 |

| 1374698_at | Rn.13635 | CoxVIIa-M | similar to cytochrome c oxidase VIIa-heart | 4.00 | 0.01 |

| 1374953_at | Rn.9543 | LOC500420 | similar to CG12279-PA | 2.61 | 0.05 |

| 1383903_at | Rn.199050 | St8 sia5 | alpha-2,8-sialyltransferase V | 2.38 | 0.05 |

| 1371172_at | Rn.11053 | Atp2b3 | ATPase, Ca2+ transporting, membrane 3 | 2.11 | 0.05 |

| 1372372_at | Rn.64439 | Rgd1306952 | similar to Ab2-225 | 1.98 | 0.05 |

| 1382105_at | Rn.23042 | Gnb5 | G protein, 5b | 1.90 | 0.05 |

| 1368016_at | Rn.163081 | Pecr | peroxisomal trans-2-enoyl-CoA reductase | 1.79 | 0.05 |

| 1368325_at | Rn.6075 | Egf | epidermal growth factor | 1.75 | 0.05 |

| 1367956_at | Rn.5653 | Ncdn | neurochondrin | 1.70 | 0.05 |

| 1368426_at | Rn.4896 | Crot | carnitine O-octanoyltransferase | 1.65 | 0.05 |

| 1383017_at | Rn.22135 | Ptprm | protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor M | 1.57 | 0.05 |

| 1393197_at | Rn.22147 | Abhd8 | abhydrolase domain containing 8 | 1.55 | 0.05 |

| 1391478_at | Rn.55564 | Znf532 | zinc finger protein 532 | 1.54 | 0.05 |

| 1397758_at | Rn.135561 | Rgd1564821 | similar to mKIAA1208 protein | 1.54 | 0.05 |

| 1374636_at | Rn.90858 | Phf17 | PHD finger protein 17 | 1.51 | 0.05 |

| 1372149_at | Rn.50 | Auh | enoyl CoA hydratase | 1.49 | 0.05 |

| 1384 302_at | Rn.186904 | Slc6a17 | solute carrier family 6, member 17 | 1.47 | 0.03 |

| 1385838_a_at | Rn.198278 | Tm2d1 | TM2 domain containing 1 | 1.33 | 0.05 |

| 1373709_at | Rn.28239 | Rgd1359592 | similar to KIAA0974 protein | 1.33 | 0.05 |

| 1371710_at | Rn.7630 | Etnk1 | ethanolamine kinase 1 | 1.30 | 0.05 |

| 1389563_at | Rn.46413 | Tmem1 | transmembrane protein 1 | 1.29 | 0.05 |

| 1374438_at | Rn.22342 | Otud4 | OTU domain containing 4 | 1.24 | 0.05 |

| 1398951_at | Rn.56498 | Rgd1308009 | similar to adrenal gland protein AD-005 | 1.22 | 0.05 |

| 1386876_at | Rn.3313 | Ac6 | adenylate cyclase 6 | 0.72 | 0.02 |

Transcripts identified as hypothetical proteins and clones, RIKEN cDNA, transcribed loci, and those that did not exist in UniGene were not included in the table. In addition, transcripts with a mean present value at 0 from the arrays were not included in the list. HCR, high capacity runners; T, trained; S, sedentary; FDR, false discovery rate.

Table 3.

GO categories overrepresented among the transcripts significantly upregulated after exercise in HCR

| GO | Name | Master List | HCR-T > HCR-S | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0008150 | Biological process | 8586 | 9 | |

| GO:0019752 | carboxylic acid metabolism | 498 | 3 | 0.013 |

| GO:0006631 | fatty acid metabolism | 203 | 2 | 0.018 |

| GO:0005575 | Cellular component | 8333 | 7 | |

| GO:0005777 | peroxisome | 85 | 2 | 0.002 |

Calculated in GeneTools (eGOn) by a Master-Target test (based on Fisher's exact test) (P < 0.05). GO, gene ontology.

Table 4.

Molecular and cellular functions and top pathways significantly upregulated after exercise in HCR

| GO | Name | HCR-T > HCR-S | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular and cellular functions | |||

| GO:0006629 | lipid metabolism | 6 | 0.0002 |

| GO:0006832 | small molecule biochemistry | 6 | 0.001 |

| Top pathways | |||

| GO:0030497 | fatty acid elongation in mitochondria | 2 | 0.0002 |

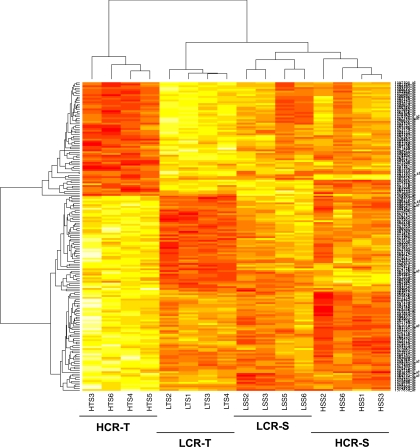

Comparing gene expressions between HCR-T and LCR-T identified 116 significantly differentially expressed transcripts (FDR ≤ 0.05) (Table 5). Several of these were associated with macromolecule metabolism (a generic term for carbohydrate, lipid and protein metabolism), indicating that metabolic processes in the soleus muscle distinguish HCR-T from LCR-T (Table 6). Of particular interest was the high expression of Igf1 and the fibrinogen-like 2 (Fgl2) in LCR-T compared with HCR-T (Table 5). To visualize the gene expression differences between all four groups, the most significantly differentially expressed transcripts are illustrated in a correlation heat map (Fig. 3).

Table 5.

Transcripts significantly up- and downregulated when comparing HCR-T with LCR-T that were associated with a transcript name

| Identifier | UniGene ID | Symbol | Transcript Name | Ratio HCR-T/LCR-T | FDR Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1381593_x_at | Rn.25717 | Rt1-Ba | RT1 class II. locus Ba = MHC class II antigen | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| 1393795_at | Rn.59710 | Zfhx1b | zinc finger homeobox 1b | 0.23 | 0.04 |

| 1392334_at | Rn.25717 | Rt1-Ba | RT1 class II, locus Ba = MHC class II antigen | 0.26 | 0.03 |

| 1398595_at | Rn.17033 | Rbm5 | RNA binding motif protein 5 | 0.36 | 0.04 |

| 1387146_a_at | Rn.11412 | Ednrb | endothelin receptor type B | 0.37 | 0.04 |

| 1386637_at | Rn.64635 | Fgl2 | fibrinogen-like 2 | 0.39 | 0.04 |

| 1375739_at | Rn.7379 | Ehd4 | EH-domain containing 4 | 0.40 | 0.04 |

| 1377663_at | Rn.25153 | Rnd3 | Rho family GTPase 3 | 0.42 | 0.04 |

| 1371499_at | Rn.2091 | Cd9 | CD9 antigen | 0.47 | 0.03 |

| 1368506_at | Rn.11065 | Rgs4 | regulator of G-protein signaling 4 | 0.50 | 0.04 |

| 1387976_at | Rn.39351 | Slc9a3r2 | solute carrier family 9, isoform 3 regulator 2 | 0.51 | 0.04 |

| 1390399_at | Rn.107553 | Crebl2 | cAMP responsive element binding protein-like 2 | 0.53 | 0.04 |

| 1370504_a_at | Rn.1476 | Pmp22 | peripheral myelin protein 22 | 0.54 | 0.03 |

| 1384136_at | Rn.21291 | Rgd1564287 | similar to mKIAA0704 protein | 0.54 | 0.04 |

| 1369735_at | Rn.52228 | Gas6 | growth arrest specific 6 | 0.55 | 0.01 |

| 1394077_at | Rn.25153 | Rnd3 | Rho family GTPase 3 | 0.55 | 0.03 |

| 1388132_at | Rn.54645 | Sfpq | splicing factor proline/glutamine rich | 0.56 | 0.04 |

| 1382599_at | Rn.6282 | Igf1 | insulin-like growth factor 1 | 0.56 | 0.05 |

| 1397508_at | Rn.26598 | Ddx18 | DEAD box polypeptide 18 | 0.56 | 0.05 |

| 1395512_at | Rn.38637 | Crlf1 | cytokine receptor-like factor 1 | 0.57 | 0.03 |

| 1389533_at | Rn.7350 | Fbln2 | vibulin 2 | 0.57 | 0.03 |

| 1382998_at | Rn.20871 | Rnmt | RNA (guanine-7-) methyltransferase | 0.58 | 0.01 |

| 1386896_at | Rn.162107 | Khdrbs1 | KH domain containing. RNA binding | 0.62 | 0.04 |

| 1370956_at | Rn.106103 | Dcn | decorin | 0.63 | 0.04 |

| 1378369_at | Rn.17371 | Rgd1564008 | similar to dapper 1 | 0.64 | 0.04 |

| 1393324_at | Rn.6473 | Jam2 | junction adhesion molecule 2 | 0.66 | 0.02 |

| 1383269_at | Rn.19719 | Rnf2 | ring finger protein 2 | 0.66 | 0.04 |

| 1368223_at | Rn.7897 | Adamts1 | A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1 | 0.72 | 0.04 |

| 1379304_at | Rn.44767 | Loc498171 | similar to inducible interleukin 11 | 0.74 | 0.05 |

| 1385298_at | Rn.73969 | Rgd1564851 | similar to putative anion transporter | 0.74 | 0.05 |

| 1378932_at | Rn.138078 | Srprb | signal recognition particle receptor B subunit | 1.22 | 0.05 |

| 1396486_x_at | Rn.170790 | Rgd1564162 | similar to Homo sapiens fetal lung specific | 1.23 | 0.04 |

| 1396382_at | Rn.62653 | Freq | frequenin homolog | 1.26 | 0.04 |

| 1389309_at | Rn.12294 | Sbno1 | Sno. strawberry notch homolog 1 | 1.27 | 0.04 |

| 1374146_at | Rn.27237 | Mad2l2 | MAD2 mitotic arrest deficient-like 2 | 1.29 | 0.04 |

| 1390120_a_at | Rn.116589 | Ring1 | ring finger protein 1 | 1.30 | 0.04 |

| 1393371_at | Rn.176450 | Zfp54 | zinc finger protein 54 | 1.32 | 0.04 |

| 1385815_at | Rn.11313 | Apeg1 | aortic preferentially expressed gene 1 | 1.32 | 0.04 |

| 1388747_at | Rn.162464 | Lcmt1 | leucine carboxyl methyltransferase 1 | 1.33 | 0.05 |

| 1373988_at | Rn.21749 | Loc690073 | similar to ferritin light chain 1 | 1.34 | 0.05 |

| 1388450_at | Rn.122513 | Ap1 gbpl | AP1 gamma subunit binding protein 1 | 1.34 | 0.04 |

| 1389335_at | Rn.47944 | Wdr22 | WD repeat domain 22 | 1.38 | 0.05 |

| 1377446_at | Rn.23848 | Rgd1563940 | similar to phosphoinositol 4-phosphate adaptor protein-2 | 1.38 | 0.04 |

| 1370025_at | Rn.94783 | Pip5k2c | phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type II γ | 1.40 | 0.04 |

| 1387178_a_at | Rn.87853 | Cbs | cystathionine β synthase | 1.40 | 0.03 |

| 1378100_at | Rn.103329 | Yeast4 | YEATS domain containing 4 | 1.40 | 0.04 |

| 1391703_at | Rn.144844 | Orc4l | origin recognition complex. subunit 4-like | 1.40 | 0.03 |

| 1373384_at | Rn.2153 | Loc691318 | protein phosphatase 2A. B subunit B γ-isoform | 1.42 | 0.04 |

| 1391282_at | Rn.13192 | Rgd1306962 | similar to dJ55C23.6 gene product | 1.45 | 0.05 |

| 1376368_at | Rn.19673 | Cuedc2 | CUE domain containing 2 | 1.48 | 0.05 |

| 1384302_at | Rn.186904 | Scl6a17 | solute carrier family 6 member 17 | 1.49 | 0.01 |

| 1399065_at | Rn.201337 | Rgd1561222 | similar to RNA binding protein with multiple splicing 2 | 1.59 | 0.05 |

| 1372171_at | Rn.139784 | Phc1 | polyhomeotic-like 1 | 1.71 | 0.05 |

| 1382105_at | Rn.23042 | Gnb5 | G protein 5b | 1.86 | 0.04 |

| 1379641_at | Rn.27421 | Rdx | radixin | 1.95 | 0.04 |

| 1394609_at | Rn.131797 | Ablim2 | actin-binding LIM protein 2 | 2.22 | 0.01 |

| 1370900_at | Rn.10092 | Myh4 | myosin heavy chain 4, skeletal muscle | 44.77 | 0.03 |

Transcripts identified as hypothetical proteins and clones, RIKEN cDNA, transcribed loci, and those that did not exist in UniGene were not included. In addition, transcripts with a mean present value at 0 from the arrays were not included in the list.

Table 6.

Biological processes overrepresented among the differentially expressed transcripts between HCR-T and LCR-T

| GO | Name | Master List | HCR-T/LCR-T | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0008150 | Biological process | 8586 | 36 | |

| GO:0048523 | negative regulation of cellular process | 936 | 11 | 0.001 |

| GO:0009892 | negative regulation of metabolism | 358 | 6 | 0.003 |

| GO:0043170 | macromolecule metabolism | 2674 | 19 | 0.007 |

Calculated in GeneTools (eGOn) by a Master-Target test (based on Fisher's exact test) (P < 0.05). The table only shows categories with more than one associated transcript.

Fig. 3.

Heat map of the most significant transcripts. Transcripts with a high expression are shown in red and transcripts with a low expression are shown in yellow.

Protein expression.

The mRNA expression of Igf1 was almost 100% higher in LCR-T compared with HCR-T (Table 5). This was in line with the measured protein levels, showing 74% increase in IGF1 protein levels in the LCR group after exercise training, versus no increase in the HCR group (Fig. 4A). The 65% stronger mRNA expression of Lars2 in LCR-S compared with HCR-S was also conserved at the protein level, as LCR-S expressed 65% more of the LARS2 protein than HCR-S (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Protein levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1, A) and leucyl-transfer RNA synthetase 2 (LARS2, B) in all the 4 groups (n = 4 in each group).

DISCUSSION

Although there was a significant difference in physical performance between HCR-S and LCR-S, only three transcripts were differentially expressed in the soleus muscle between the groups. After exercise training, significant transcriptional changes occurred in both HCR and LCR. However, the changes were much more pronounced in HCR than LCR, indicating a substantial difference in the ability of transcriptional adaptation to exercise.

Inborn differences in soleus muscle gene expression.

We have previously reported that LCR-S expressed low levels of several proteins required for mitochondrial biogenesis and function in the soleus muscle, compared with HCR-S (43). Yet, in the present study, only three genes were differentially expressed between HCR-S and LCR-S.

One of the differentially expressed transcripts between HCR-S and LCR-S had homology with the human mitochondrial gene Lars2. This transcript was more abundant in LCR-S than HCR-S, and upregulation of the human homolog is regarded as a hallmark of the mitochondrial DNA A-to-G point mutation in the leucyl-transfer RNA [tRNALeu(UUR)] (29). The mutation generates structural and functional defects of the tRNALeu(UUR) that disrupts intramitochondrial protein synthesis (5). Humans suffering from this mutation are diagnosed with the disorder “Mitochondrial myopathy, Encephalopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Stroke-like episodes” (MELAS), which involves maternally inherited diabetes and mitochondrial dysfunction (23, 31). In humans, such a mutation causes impaired O2 extraction from blood, hyperglycemia, and exercise intolerance (28, 31, 34), which is in accordance with the previously reported characteristics of LCR-S (8, 11, 16, 20, 24, 43). This finding suggests that low aerobic fitness with a concomitant development of metabolic dysfunction (19, 39, 43) also may predispose for a development of a MELAS-like pathology, albeit at this stage, this observation is only preliminary and serves as a hypothesis for further studies.

The low number of genes differentially expressed between HCR-S and LCR-S in this study is in contrast to the earlier reported differences between HCR-S and LCR-S at protein level. We cannot rule out the possibility that the low number of differentially expressed genes between HCR-S and LCR-S are at least partly explained by the low number of animals included in each group.

Response to exercise training in HCR and LCR.

Rats participating in the high-intensity interval program display most of the cardiorespiratory changes observed in humans, as increased VO2max, physiological hypertrophy, improved endothelial function, and reduced resting heart rate (41, 42). Most of these changes occur within the first 4 wk of endurance training, and VO2max reaches a plateau after 6–8 wk (41, 42). Expression of regulatory and metabolic genes tends to occur within few hours after exercise and often returns to baseline within 24 h (7, 32). Sample collection after 8 wk of exercise training, 48 h after the last exercise bout, means that we miss several of the differentially expressed genes. However, this was intended, since we were interested in the long-term adaptations to exercise. Even so, 58 transcripts were found upregulated by exercise in the HCR group, whereas one transcript was upregulated in the LCR group. In both HCR and LCR, exercise training upregulated a transcript similar to a subunit in complex IV. Increased expression of complex IV subunits is a common feature of exercise training and a marker of mitochondrial content and biogenesis (2, 33). From the physiological data, it appears that the endurance training led to a “normalization” of the LCR phenotype to the baseline of the HCR in terms of VO2max and running speed. However, as only one skeletal muscle transcript was differentially expressed after exercise training in LCR, the improvements in VO2max and running speed are likely to involve changes in other organ systems, e.g., the heart (4).

In HCR, adaptation to exercise involved increased expression of genes involved in lipid/fatty acid metabolism (e.g., Crot, Auh) and fatty acid elongation in the mitochondria (e.g., Pecr). Moreover, the peroxisomes seemed to be of particular importance for the adaptations to exercise in the soleus muscle of HCR. Previously, peroxisomes have largely been overlooked with respect to maintaining a healthy cellular lipid environment in the cells, although they are ubiquitously expressed and have a wide range of cellular functions, including a primary role in FAO (40). Since very long chained fatty acids exclusively can be oxidized by the peroxisomes, increased peroxisomal activity might be important for enhanced FAO and energy production in exercise-trained muscle. In this study, exercise training triggered expression of the peroxisomal gene Crot in HCR, which may indicate accelerated FAO by increased transfer of chain-shortened fatty acids from the peroxisomes to the mitochondria (38). Furthermore, increased expression of the FAO enzyme Auh suggested increased energy production in the mitochondria. In line with the indications from our data, previous studies have shown that exercise trained muscles oxidize more fatty acids (18, 35). Consequently, glycogen stores are spared, hypoglycemia-induced fatigue is delayed, and exercise capacity is increased (18, 35). Mechanisms responsible for enhanced FAO in exercise-trained muscle are not completely elucidated; however, increased expression of Crot and Auh might be important mediators.

Surprisingly, the Myh4 transcript was 34 times upregulated after exercise training in the HCR group. Upregulation of this fast-twitch myosin heavy chain might shift the fiber type in HCR-T toward more fast fibers. However, it may also reflect a repair of damaged fast fibers after exercise training or a switch between different forms of fast fibers. When performing fiber-typing of formalin-fixed soleus muscles, we found no signs of an increased number of fast fibers in HCR-T, but rather a trend toward fewer fast fibers in HCR-T (P = 0.07). In line with our results from the fiber typing, stimuli like endurance training most often result in a shift from fast to slow fibers. The reason for the Myh4 mRNA upregulation in HCR-T remains therefore uncertain.

Exercise training was accompanied by increased expression of ATPase, Ca2+ transporting, membrane 3 (Atp2b3) in HCR soleus muscle, which encodes one of four mammalian proteins constituting the plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPases that mediates the extrusion of intracellular Ca2+. These pumps are responsible for the resetting and maintenance of resting levels of intracellular [Ca2+] and are involved in local regulation of Ca2+ signaling. Increased expression of Atp2b3 may indicate increased abundance of plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPases after exercise training in the HCR group and should be further studied. To our knowledge, increased expression of Atp2b3 has not previously been associated with exercise training.

Fatty acid elongation in mitochondria was significantly upregulated in the HCR group and was mediated by Pecr, a key enzyme in the chain elongation pathway (6). The pathway involves elongation of either palmitate or other dietary fatty acids to give rise to longer fatty acids. Fatty acid elongation is important to store energy and to synthesize lipids important for cellular functions, as for instance membrane components.

Regarding different responses to exercise training in terms of gene expression between HCR and LCR, we cannot rule out the possibility that biological noise such as activity levels in the cages may contribute.

Differences between soleus muscle of HCR and LCR after the exercise intervention.

Eight weeks of exercise training produced differences between the strains for regulation of metabolism, particularly in macromolecular metabolism. Igf1 was significantly more expressed in LCR-T than HCR-T. IGF1 plays a major role in exercise-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy and strength improvements. IGF1 is highly inducible with exercise, and the level often keeps increasing for 2 days after just a single bout of exercise (13). At first, a higher exercise-induced increase in Igf1 mRNA in the LCR group compared with the HCR group was not easily explained. However, when performing Western blot, we found twice as much IGF1 in the HCR-S compared with the LCR-S. That is, the LCR had a considerably lower basis of IGF1 before the exercise intervention. Reduced levels of IGF1 are also reported in animals and humans with HF (14, 36). Skeletal muscle IGF1 level correlates with muscle cross-sectional area, and low levels of IGF1 may contribute to the development of muscular dysfunction and muscle atrophy (14). The low level of IGF1 in LCR-S might be explained by a potential growth hormone (GH) deficiency, and is probably a contributing factor to impaired exercise capacity. The ability of exercise to increase IGF1, by means of increased work overload and passive stretch, does however seem to be maintained in LCR. The reason why exercise training had no impact on the IGF1 levels in the HCR group remains unknown.

Interestingly, the negative regulator of growth, Adamts1 (A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1) was more expressed in LCR-T than HCR-T. Upregulation of Adamts1 is associated with muscle weakness, muscle wasting, and various inflammatory processes (25). High expression of Adamts1 in LCR-T suggests an ongoing inflammatory process in the soleus and impaired muscle growth, compared with HCR-T.

Increased fibrinolytic potential is a well-known beneficial effect of long-term endurance training (44). Fgl2, a recently discovered prothrombinase, was less expressed in the soleus muscle of HCR-T compared with LCR-T (45). Due to superior fitness in HCR-T, it seems likely that HCR-T has a superior antithrombotic status. To our knowledge, regulation of Fgl2 in skeletal muscle has not previously been associated with exercise training.

Conclusion

Gene expression profiling of rats with inborn high or low VO2max indicated only minor differences in soleus muscle gene expression at a sedentary state. This implies that the stimulus for gene expression is about the same for the extremities in VO2max as long as the animals remain sedentary. However, the inborn level of fitness seems to affect the transcriptional adaption to exercise, as more genes were upregulated in the HCR group than in the LCR group after similar exercise programs. HCR seem to adapt well to exercise training, whereas surprisingly few genes were induced by exercise training in LCR. This implies that subjects born with different fitness level may have different responses to the same exercise program.

GRANTS

The study was supported by grants from the Norwegian Council on Cardiovascular Disease, the Research Council of Norway (funding for Outstanding Young Investigators), Ingrid and Torleif Hoel's Legacy, Halvor Holta's Legacy, Rakel and Otto Kr. Bruun's Legacy, Jon H. Andresen's Medical Fund, Prof. Leif Tronstad's Fund, the Blix Fund for the Promotion of Medical Science, the Foundation for Cardiovascular Research at St. Olav's Hospital, Trondheim, Norway, and by National Center for Research Resources Grant RR-17718 (USA).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Trine Skoglund, Ragnhild Røsbjørgen, Ingerid Arbo, and Marianne Vinje for technical assistance and acknowledge the expert care of the LCR/HCR rat colony provided by Lori Gilligan and Nathan Kanner.

Address for reprint requests and other correspondence: U. Wisløff, Norwegian Univ. of Science and Technology, Circulation and Medical Imaging, Olav Kyrres gt. 3, Trondheim, 7489, Norway (e-mail: ulrik.wisloff@ntnu.no).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beisvag V, Junge FK, Bergum H, Jolsum L, Lydersen S, Gunther CC, Ramampiaro H, Langaas M, Sandvik AK, Laegreid A. GeneTools–application for functional annotation and statistical hypothesis testing. BMC Bioinformatics 7: 470, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bengtsson J, Gustafsson T, Widegren U, Jansson E, Sundberg CJ. Mitochondrial transcription factor A and respiratory complex IV increase in response to exercise training in humans. Pflügers Arch 443: 61–66, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Statistical Society Series B: 289–300, 1995.

- 4.Bye A, Langaas M, Høydal MA, Kemi OJ, Heinrich G, Koch LG, Britton SL, Najjar SM, Ellingsen Ø, Wisløff U. Aerobic capacity-dependent differences in cardiac gene expression. Physiol Genomics 33: 100–109, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chomyn A, Enriquez JA, Micol V, Fernandez-Silva P, Attardi G. The mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episode syndrome-associated human mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) mutation causes aminoacylation deficiency and concomitant reduced association of mRNA with ribosomes. J Biol Chem 275: 19198–19209, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das AK, Uhler MD, Hajra AK. Molecular cloning and expression of mammalian peroxisomal trans-2-enoyl-coenzyme A reductase cDNAs. J Biol Chem 275: 24333–24340, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flück M, Hoppeler H. Molecular basis of skeletal muscle plasticity–from gene to form and function. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 146: 159–216, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foley TE, Greenwood BN, Day HE, Koch LG, Britton SL, Fleshner M. Elevated central monoamine receptor mRNA in rats bred for high endurance capacity: implications for central fatigue. Behav Brain Res 174: 132–142, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol 5: R80, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibbs RA, Weinstock GM, Metzker ML, Muzny DM, Sodergren EJ, Scherer S, Scott G, Steffen D, Worley KC, Burch PE, Okwuonu G, Hines S, Lewis L, DeRamo C, Delgado O, Dugan-Rocha S, Miner G, Morgan M, Hawes A, Gill R, Celera Holt RA, Adams MD, Amanatides PG, Baden-Tillson H, Barnstead M, Chin S, Evans CA, Ferriera S, Fosler C, Glodek A, Gu Z, Jennings D, Kraft CL, Nguyen T, Pfannkoch CM, Sitter C, Sutton GG, Venter JC, Woodage T, Smith D, Lee HM, Gustafson E, Cahill P, Kana A, Doucette-Stamm L, Weinstock K, Fechtel K, Weiss RB, Dunn DM, Green ED, Blakesley RW, Bouffard GG, De Jong PJ, Osoegawa K, Zhu B, Marra M, Schein J, Bosdet I, Fjell C, Jones S, Krzywinski M, Mathewson C, Siddiqui A, Wye N, McPherson J, Zhao S, Fraser CM, Shetty J, Shatsman S, Geer K, Chen Y, Abramzon S, Nierman WC, Havlak PH, Chen R, Durbin KJ, Egan A, Ren Y, Song XZ, Li B, Liu Y, Qin X, Cawley S, Worley KC, Cooney AJ, D'Souza LM, Martin K, Wu JQ, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Jackson AR, Kalafus KJ, McLeod MP, Milosavljevic A, Virk D, Volkov A, Wheeler DA, Zhang Z, Bailey JA, Eichler EE, Tuzun E, Birney E, Mongin E, Ureta-Vidal A, Woodwark C, Zdobnov E, Bork P, Suyama M, Torrents D, Alexandersson M, Trask BJ, Young JM, Huang H, Wang H, Xing H, Daniels S, Gietzen D, Schmidt J, Stevens K, Vitt U, Wingrove J, Camara F, Mar Alba M, Abril JF, Guigo R, Smit A, Dubchak I, Rubin EM, Couronne O, Poliakov A, Hubner N, Ganten D, Goesele C, Hummel O, Kreitler T, Lee YA, Monti J, Schulz H, Zimdahl H, Himmelbauer H, Lehrach H, Jacob HJ, Bromberg S, Gullings-Handley J, Jensen-Seaman MI, Kwitek AE, Lazar J, Pasko D, Tonellato PJ, Twigger S, Ponting CP, Duarte JM, Rice S, Goodstadt L, Beatson SA, Emes RD, Winter EE, Webber C, Brandt P, Nyakatura G, Adetobi M, Chiaromonte F, Elnitski L, Eswara P, Hardison RC, Hou M, Kolbe D, Makova K, Miller W, Nekrutenko A, Riemer C, Schwartz S, Taylor J, Yang S, Zhang Y, Lindpaintner K, Andrews TD, Caccamo M, Clamp M, Clarke L, Curwen V, Durbin R, Eyras E, Searle SM, Cooper GM, Batzoglou S, Brudno M, Sidow A, Stone EA, Venter JC, Payseur BA, Bourque G, Lopez-Otin C, Puente XS, Chakrabarti K, Chatterji S, Dewey C, Pachter L, Bray N, Yap VB, Caspi A, Tesler G, Pevzner PA, Haussler D, Roskin KM, Baertsch R, Clawson H, Furey TS, Hinrichs AS, Karolchik D, Kent WJ, Rosenbloom KR, Trumbower H, Weirauch M, Cooper DN, Stenson PD, Ma B, Brent M, Arumugam M, Shteynberg D, Copley RR, Taylor MS, Riethman H, Mudunuri U, Peterson J, Guyer M, Felsenfeld A, Old S, Mockrin S, Collins F. Genome sequence of the Brown Norway rat yields insights into mammalian evolution. Nature 428: 493–521, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez NC, Kirkton SD, Howlett RA, Britton SL, Koch LG, Wagner HE, Wagner PD. Continued divergence in VO2max of rats artificially selected for running endurance is mediated by greater convective blood O2 delivery. J Appl Physiol 101: 1288–1296, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC Jr, Lenfant C. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation 109: 433–438, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haddad F, Adams GR. Selected contribution: acute cellular and molecular responses to resistance exercise. J Appl Physiol 93: 394–403, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hambrecht R, Schulze PC, Gielen S, Linke A, Mobius-Winkler S, Yu J, Kratzsch JJ, Baldauf G, Busse MW, Schubert A, Adams V, Schuler G. Reduction of insulin-like growth factor-I expression in the skeletal muscle of noncachectic patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 39: 1175–1181, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawley JA, Spargo FJ. It's all in the genes, so pick your parents wisely. J Appl Physiol 100: 1751–1752, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henderson KK, Wagner H, Favret F, Britton SL, Koch LG, Wagner PD, Gonzalez NC. Determinants of maximal O2 uptake in rats selectively bred for endurance running capacity. J Appl Physiol 93: 1265–1274, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holloszy JO Biochemical adaptations in muscle. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial oxygen uptake and respiratory enzyme activity in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 242: 2278–2282, 1967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holloszy JO, Coyle EF. Adaptations of skeletal muscle to endurance exercise and their metabolic consequences. J Appl Physiol 56: 831–838, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howlett RA, Gonzalez NC, Wagner HE, Fu Z, Britton SL, Koch LG, Wagner PD. Selected contribution: skeletal muscle capillarity and enzyme activity in rats selectively bred for running endurance. J Appl Physiol 94: 1682–1688, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Høydal MA, Wisløff U, Kemi OJ, Britton SL, Koch LG, Smith GL, Ellingsen Ø. Nitric oxide synthase type-1 modulates cardiomyocyte contractility and calcium handling: association with low intrinsic aerobic capacity. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 14: 319–325, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucl Acids Res 31: e15, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kavanagh T, Mertens DJ, Hamm LF, Beyene J, Kennedy J, Corey P, Shephard RJ. Peak oxygen intake and cardiac mortality in women referred for cardiac rehabilitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 42: 2139–2143, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi Y, Momoi MY, Tominaga K, Momoi T, Nihei K, Yanagisawa M, Kagawa Y, Ohta S. A point mutation in the mitochondrial tRNA(Leu)(UUR) gene in MELAS (mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 173: 816–822, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koch LG, Britton SL. Artificial selection for intrinsic aerobic endurance running capacity in rats. Physiol Genomics 5: 45–52, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuno K, Kanada N, Nakashima E, Fujiki F, Ichimura F, Matsushima K. Molecular cloning of a gene encoding a new type of metalloproteinase-disintegrin family protein with thrombospondin motifs as an inflammation associated gene. J Biol Chem 272: 556–562, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magliano DJ, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ. How to best define the metabolic syndrome. Annals Med 38: 34–41, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mole PA, Oscai LB, Holloszy JO. Adaptation of muscle to exercise. Increase in levels of palmityl Coa synthetase, carnitine palmityltransferase, and palmityl Coa dehydrogenase, and in the capacity to oxidize fatty acids. J Clin Invest 50: 2323–2330, 1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan-Hughes JA, Sweeney MG, Cooper JM, Hammans SR, Brockington M, Schapira AH, Harding AE, Clark JB. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) diseases: correlation of genotype to phenotype. Biochim Biophys Acta 1271: 135–140, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munakata K, Iwamoto K, Bundo M, Kato T. Mitochondrial DNA 3243A>G mutation and increased expression of LARS2 gene in the brains of patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 57: 525–532, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myers J, Prakash M, Froelicher V, Do D, Partington S, Atwood JE. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Med 346: 793–801, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onishi H, Inoue K, Osaka H, Nagatomo H, Ando N, Yamada Y, Suzuki K, Hanihara T, Kawamoto S, Okuda K. [MELAS associated with diabetes mellitus and point mutation in mitochondrial DNA]. [No to shinkei] Brain Nerve 44: 259–264, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pilegaard H, Osada T, Andersen LT, Helge JW, Saltin B, Neufer PD. Substrate availability and transcriptional regulation of metabolic genes in human skeletal muscle during recovery from exercise. Metabolism Clin Exp 54: 1048–1055, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puntschart A, Claassen H, Jostarndt K, Hoppeler H, Billeter R. mRNAs of enzymes involved in energy metabolism and mtDNA are increased in endurance-trained athletes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 269: C619–C625, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rusanen H, Majamaa K, Hassinen IE. Increased activities of antioxidant enzymes and decreased ATP concentration in cultured myoblasts with the 3243A–>G mutation in mitochondrial DNA. Biochim Biophys Acta 1500: 10–16, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saltin B, Astrand PO. Free fatty acids and exercise. Am J Clin Nutr 57: 752S–757S, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulze PC, Gielen S, Adams V, Linke A, Mobius-Winkler S, Erbs S, Kratzsch J, Hambrecht R, Schuler G. Muscular levels of proinflammatory cytokines correlate with a reduced expression of insulinlike growth factor-I in chronic heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol 98: 267–274, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smyth GK Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genetics Mol Biol 3: Article3, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Verhoeven NM, Roe DS, Kok RM, Wanders RJ, Jakobs C, Roe CR. Phytanic acid and pristanic acid are oxidized by sequential peroxisomal and mitochondrial reactions in cultured fibroblasts. J Lipid Res 39: 66–74, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh B, Hooks RB, Hornyak JE, Koch LG, Britton SL, Hogan MC. Enhanced mitochondrial sensitivity to creatine in rats bred for high aerobic capacity. J Appl Physiol 100: 1765–1769, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wanders RJ, Waterham HR. Biochemistry of mammalian peroxisomes revisited. Ann Rev Biochem 75: 295–332, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wisløff U, Helgerud J, Kemi OJ, Ellingsen Ø. Intensity-controlled treadmill running in rats: VO2max and cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H1301–H1310, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wisløff U, Loennechen JP, Falck G, Beisvag V, Currie S, Smith G, Ellingsen Ø. Increased contractility and calcium sensitivity in cardiac myocytes isolated from endurance trained rats. Cardiovasc Res 50: 495–508, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wisløff U, Najjar SM, Ellingsen Ø, Haram PM, Swoap S, Al-Share Q, Fernström M, Rezaei K, Lee SJ, Koch LG, Britton SL. Cardiovascular risk factors emerge after artificial selection for low aerobic capacity. Science 307: 418–420, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Womack CJ, Nagelkirk PR, Coughlin AM. Exercise-induced changes in coagulation and fibrinolysis in healthy populations and patients with cardiovascular disease. Sports Med (Auckland, NZ) 33: 795–807, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuwaraj S, Ding J, Liu M, Marsden PA, Levy GA. Genomic characterization, localization, and functional expression of FGL2, the human gene encoding fibroleukin: a novel human procoagulant. Genomics 71: 330–338, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]