Chile has maintained a dual health care system under which its citizens can voluntarily opt for coverage by either the public National Health Insurance Fund or any of the country's private health insurance companies. Currently, 68% of the population is covered by the public fund and 18% by private companies. The remaining 14% is covered by other not-for-profit agencies or has no specific coverage. The system's duality has led to increasing inequalities, prompting the Chilean government to introduce major reforms in health care provision.1 In this article, we outline Chile's recent reforms and the challenges surrounding their implementation.

Chile's health care system is funded by a universal income tax deduction equal to 7% of every worker's wage. Whereas the National Health Insurance Fund is wholly supported by the government using general tax revenue, many private health insurance companies encourage people to pay a variable extra on top of the 7% premium to upgrade their basic health plans.

Because of this arrangement, the public and private health subsystems in Chile have existed almost completely separate from each other rather than coordinating to achieve common health objectives. In the public sector, primary care services are relatively well organized, delivering free medical, dental, nursing and midwifery services at local health centres administered and owned by local municipalities. Secondary and tertiary care are provided by a network of public outpatient and hospital facilities with different levels of complexity. By contrast, the private sector has neglected the development of primary care networks, focusing mainly on the delivery of secondary and tertiary care.

The structural segmentation of Chile's health care system has resulted in low-income and high-risk populations being served mainly by the public sector, while high-income and low-risk populations are generally treated in the private sector.2 Low investment in preventive medicine and health promotion has increased health care gaps among people in a country experiencing a late stage of epidemiologic transition away from infectious diseases to degenerative diseases.3,4

To address the issue, the Chilean Ministry of Health in 2000 set a number of health objectives for the decade and proposed several bills to reform the health care system. The following bills were submitted to the Chilean parliament: the Health Authority and Management Law, which separates regulatory functions from those of health service providers; the Private Health Law, which improves private sector regulations; the Financing Government Expenditure Law, which secures additional resources required to finance the reform; and the Regime of Explicit Guarantees in Health Law, which establishes a universal health plan with explicit guarantees.

These reforms would not have progressed had it not been for: the consistent and energetic role of the executive power; counteraction of political opposition; the use of human rights rhetoric in discussions on reform; the role of the senate in mediating between conflicting interests of stakeholders; a move on the part of the government to mitigate the opposition of health professionals; and the emergence of mediating parties, such as civil society organizations, that managed to involve all political actors in a broader and less politicized discussion.5

The universal health care plan

The key elements defined by the Regime of Explicit Guarantees in Health Law6 are:

A medical benefits package that consists of a prioritized list of diagnoses and treatments for 56 health conditions (see Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/179/12/1289/DC1)

Universal coverage for all citizens

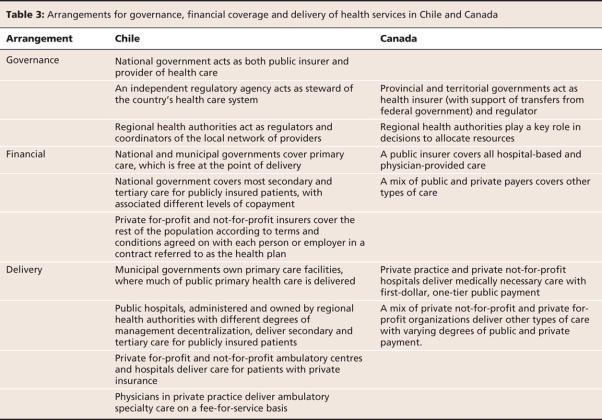

A set of guarantees specific to the universal health plan and enforced by law that includes access, quality, opportunity and financial protection.

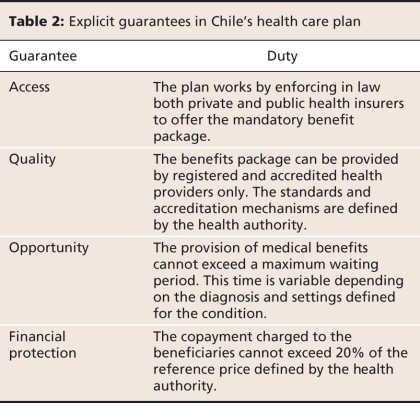

Prioritization of the health conditions and treatments was based originally on an algorithm that included a number of sequential variables (Table 1). Access and opportunity guarantees, on the other hand, were established mainly on the basis of experts' opinions for each condition. The guarantee of financial protection was defined using a number of studies that analyzed the impact of covering the universal health plan on the financing of the health care system. These guarantees are shown in Table 2.

Table 1

Table 2

The universal health plan is delivered by pre-arranged provider networks established by both the public and private sectors. The list of conditions and treatments covered by the plan is periodically revised to adapt priorities to new epidemiologic situations.

Comparing Chile's reform process with that of other countries

The design of Chile's universal health plan is similar to that of one implemented in the state of Oregon — with a crucial homegrown difference. In the Oregon Health Plan certain health services are explicitly excluded in favour of others. In Chile, to avoid controversial rationing of health services, the plan must not reduce in any way the medical benefits formerly provided for health conditions not included in the health plan.7,8

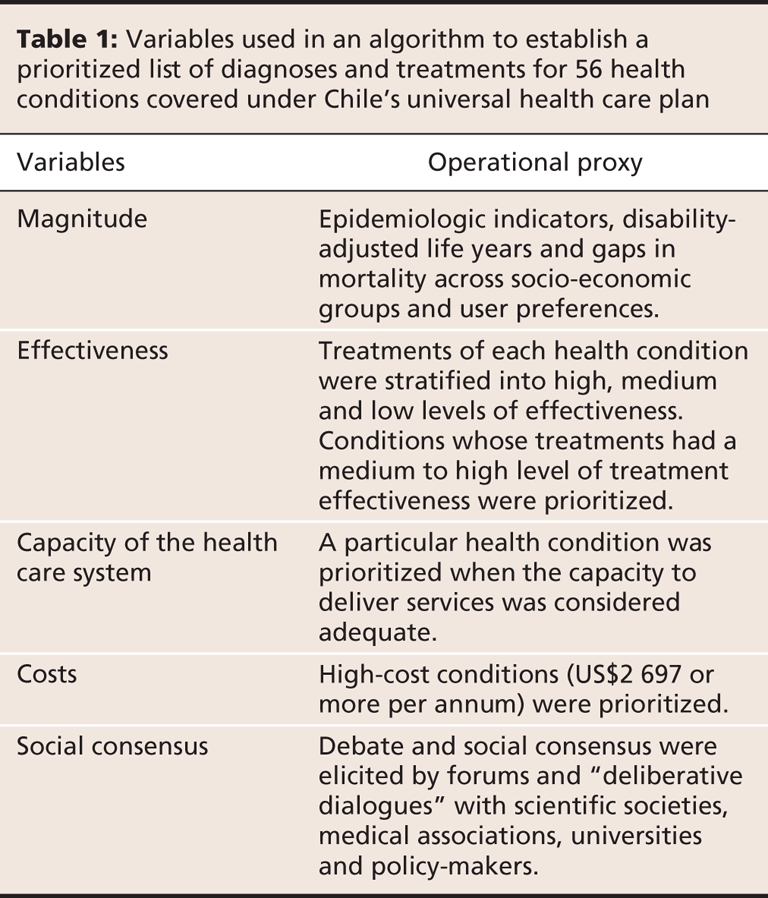

When compared with that of Canada's health care system, the basic structure of the Chilean system appears more centralized. In Chile the public sector plays a double role, acting not only as the main insurer but also as the largest health care provider in the country. A detailed, head-to-head comparison between Chile and Canada, based on the framework developed by Lavis and colleagues,9 is provided in Table 3.

Table 3

Using the “control knobs” framework of Hsiao and colleagues,10 we have compared Chile's reform process with that of several other relevant countries based on 5 core characteristics: organization, financing, payment, regulation and persuasion.

Organizationally, Chile's health care reform strengthened decentralization, which not only empowered local decision-makers but also made them more responsible for outcomes, analogous to the 1993 reform in Burkina Faso.11,12

As in Canada, adequate funding for the Chilean reform was secured by the government through an increase in taxation.13 Nonetheless, these resources accounted for only the public sector; members of the private sector had to raise their premiums to cover the costs of the health plan.

Financially, payment methods between insurers and providers did not change significantly because of the reform. However, some modifications have been observed in the private system as providers now compete to offer the cheapest alternatives using a scheme similar to preferred provider organizations in the United States.14

The inspection of quality standards and financial oversight of the health care system are performed by an independent agency of the government called the Superintendence of Health. Similar agencies exist in Colombia15 and other Latin American countries.

The need to persuade health care consumers has been a major concern during the implementation of Chile's health plan. The Ministry of Health has invested in several marketing strategies aimed at generating more active participation of the public by encouraging people to demand their rights. But it is probably too soon to evaluate the impact on this area, since this kind of campaign, like the one launched against tobacco in the United States,16 will show measurable effects on consumer preferences many decades after being implemented.

Challenges

Chile's complex process of setting health care priorities has been praised and given a favourable welcome in the national and international policy communities.17 However, a number of challenges remain that should be addressed to achieve proposed goals.

First, the process of setting limits and priorities has been questioned for its legitimacy and fairness.18 Key elements of a fair process have been described and labelled by Daniels as “accountability for reasonableness”.19 Many of these elements, such as transparency, appeals, and procedures for revising decisions, seem to be absent from the debates about our reform process. Although there are institutions, mechanisms and procedures to revise those conditions and interventions that are guaranteed, the program lacks clearly established mechanisms for social accountability.

Second, the process has emphasized the implementation and measurement of all of the health plan's guarantees except that related to quality. Current discussions have stressed the need for accreditation of health care organizations that deliver services under the plan, which seems more related to the issue of safety than to guaranteeing quality. On the other hand, a number of clinical guidelines aimed at directing and improving the clinical decision-making process have been issued, which seems to be a step closer to a guarantee of quality of care.

Third, the implementation of the universal health plan has not been addressed seriously until now. The assumption that organizations and health professionals would comply immediately with the laws when they were issued was naive. For instance, the administrative burden of recording information each time a general practitioner makes a presumptive diagnosis of hypertension or diabetes (conditions covered under the health plan) is huge. Additionally, there is a strong distrust by many health professional associations in the performance of the health system reform. Their uncertainty has been fuelled by the lack of transparency in the initial priority-setting process and by unsolved problems with the central information system where data are still manually codified. Not surprisingly, therefore, many health professionals do not recommend the use of guarantees, even though they are obliged to do so by law.

Conclusion

Chile's universal health care plan has been of great significance from both a social policy and a legal perspective. It establishes a health care system that incorporates a number of guarantees. Although it is still early to comprehensively evaluate the reform, we think a number of challenges should be addressed at this stage to improve the health care system. Three issues require urgent analysis: the legitimacy and fairness of the priority-setting process at the policy-making level, the implementation of the guarantee related to quality of care and the need for processes and strategies to implement the health plan at the organizational level. A number of initiatives developed to introduce scientific evidence into health policy could be used to tackle these challenges.20,21 Such initiatives would require a much closer collaboration between policy-makers and researchers with a common aim of improving the general health of the Chilean population.

Key points.

Chile has recently implemented health care reform to address growing inequalities.

The reform establishes a list of 56 health conditions and treatments for which coverage is guaranteed by law.

The list was prioritized using a progressive set of criteria that included burden of disease, effectiveness of treatments, capacity of the health system, financial burden and social consensus.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors contributed to the writing of this article and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Gabriel Bastías, Department of Public Health, School of Medicine, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Marcoleta 434 Piso 1, Santiago, Chile; fax 56-26331840; gbastias@med.puc.cl

REFERENCES

- 1.Erazo A. Series de documentos de trabajo n° 1: Modernización del seguro público de salud. Santiago (Chile): Fondo Nacional de Salud; 2005. Available: www.fonasa.cl/prontus_fonasa/site/artic/20070413/asocfile/doc_trab_1.pdf (accessed 2007 Dec 4).

- 2.Arteaga O, Astorga I, Pinto AM. Inequalities in public health care provision in Chile. Cad Saude Publica 2002;18:1053-66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Szot MJ. Demographic–epidemiologic transition in Chile, 1960–2001. Rev Esp Salud Publica 2003;77:605-13. [PubMed]

- 4.Concha M, Aguilera X. Burden of disease in Chile. Santiago (Chile): Government of Chile Ministry of Health (MINSAL); 1996.

- 5.Drago M. La reforma al sistema de salud chileno desde la perspectiva de los derechos humanos. Santiago (Chile): Naciones Unidas (CEPAL); 2006.

- 6. Chile. Gobierno de Chile. Ministerios de Hacienda y Salud. Decreto nº 44 Aprueba garantías explícitas en salud del régimen general de garantías en salud; 2007.

- 7. Bodenheimer T. The Oregon Health Plan — lessons for the nation. First of two parts. N Engl J Med 1997;337:651-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Oberlander J, Marmor T, Jacobs L. Rationing medical care: rhetoric and reality in the Oregon Health Plan. CMAJ 2001;164:1583-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Lavis JN, Becerra Posada F, Haines A, et al. Use of research to inform public policymaking. Lancet 2004;364:1615-21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Roberts MJ, Hsiao W, Berman P, et al. Getting health reform right: a guide to improving performance and equity. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2004.

- 11.Bodart C, Servais G, Mohamed YL, et al. The influence of health sector reform and external assistance in Burkina Faso. Health Policy Plan 2001;16:74-86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Haddad S, Nougtara A, Fournier P. Learning from health system reforms: lessons from Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health 2006;11:1889-97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). Canada. In: Health in the Americas, 2007. Volume II — Countries. Washington (DC): The Organization; 2007. Available: www.paho.org/HIA/archivosvol2/paisesing/Canada%20English.pdf (accessed 2008 Aug 22).

- 14.Hamer R, Anderson D. PPO operations and markets. St. Paul (MN): InterStudy Publications; 2000.

- 15.Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). Columbia. In: Health in the Americas, 2007. Volume II — Countries. Washington (DC): The Organization; 2007. Available: www.paho.org/HIA/archivosvol2/paisesing/Colombia%20English.pdf (accessed 2008 Aug 22).

- 16.Brandt A. The rise & fall of the cigarette: A cultural history of smoking in the U.S. New York (NY): Basic Books; 1998.

- 17.Sojo A. La garantía de prestaciones en salud en América Latina: equidad y reorganización de los cuasimercados a inicios del milenio. [Estudios y perspectivas series]. Mexico City (Mexico): Naciones Unidas; 2006. ECLAC Subregional. Available: www.cepal.org/publicaciones/xml/1/23871/Serie-44-vf.pdf (accessed 2008 Aug 22).

- 18.Unger JP, De Paepe P, Cantuarias GS, et al. Chile's neoliberal health reform: an assessment and a critique. PLoS Med 2008;5:e79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Daniels N. Accountability for reasonableness (editorial). BMJ 2000;321:1300-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Sabik LM, Lie RK. Priority setting in health care: lessons from the experience of eight countries. Int J Equity Health 2008;7:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Ham C, Robert G, editors. Reasonable rationing. International experience of priority setting in health care. Buckingham (UK): Open University Press; 2003.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.