Abstract

Opioid receptor agonists and antagonists have profound effects on cocaine-induced hyperactivity and conditioned reward. Recently, the role specifically of the mu opioid receptor has been demonstrated based on the finding that intracerebroventricular administration of the selective mu opioid receptor antagonist, CTAP, can attenuate cocaine-induced behaviors. The purpose of the present study was to determine the location of mu opioid receptors that are critical for cocaine-induced reward and hyperactivity. Adult male Sprague Dawley rats received injections of CTAP into the caudate putamen, the rostral or caudal ventral tegmental area (VTA) or the medial shell or core of the nucleus accumbens prior to cocaine to determine the role of mu opioid receptors in cocaine-induced reward and hyperactivity. Cocaine-induced reward was assessed using an unbiased conditioned place preference procedure. Results demonstrate that animals pre-treated with CTAP into the nucleus accumbens core or rostral VTA, but not the caudal VTA, caudate putamen or medial nucleus accumbens shell, during conditioning with cocaine showed an attenuation of the development of cocaine-induced place preference. In contrast, CTAP injected into the nucleus accumbens shell but not the core attenuated the expression of cocaine place preference. Intra-nucleus accumbens core, caudate putamen or caudal VTA CTAP significantly attenuated cocaine-induced hyperactivity. In addition, the number of cFos positive cells was increased in the motor cortex, medial and ventromedial aspects of the nucleus accumbens shell, basolateral amygdala and caudal VTA during the expression of cocaine place preference, and this increase was attenuated in the animals that received intra-accumbens core CTAP during daily cocaine conditioning. These results demonstrate the importance of mu opioid receptors in the nucleus accumbens and VTA in cocaine-induced reward and hyperactivity and suggest that some aspects of the behavioral effects of cocaine are mediated by endogenous activation of mu opioid receptors in these brain regions.

Keywords: Conditioned Place Preference, cFos, Hyperactivity, Nucleus Accumbens, Ventral Tegmental Area, Reward

Cocaine is a psychomotor stimulant that facilitates monoaminergic neurotransmission by binding to transporters and inhibiting the reuptake of dopamine, serotonin and norepinepherine into presynaptic neurons (Heikkila et al., 1975; Nicolaysen and Justice, 1988). Many of the behavioral effects of cocaine, including its locomotor-activating and reinforcing properties, have been attributed to the ability of cocaine to enhance dopaminergic activity (Ritz et al., 1987). In addition to its direct effects on monoamine neurotransmitters, cocaine impacts other neurotransmitter systems including the endogenous opioid system. Cocaine alters levels of endogenous opioid peptides (Hurd and Herkenham, 1993; Olive et al., 2001; Roth-Deri et al., 2003) and has profound effects on the expression and function of opioid receptors (Hammer, 1989; Unterwald et al., 1994; Izenwasser et al., 1996; Schroeder et al., 2003). Together, dopamine and opioid peptides modulate rewarding behaviors and locomotor activity (Fink and Smith, 1980; Roberts and Koob, 1982).

In animal models of drug reinforcement, the non-selective opioid receptor antagonists, naloxone and naltrexone, can reduce the rewarding effects of cocaine (Bain and Kornetsky 1987; Corrigall and Coen, 1991; Bilsky et al., 1992) suggesting an interaction between central opioid and dopaminergic systems in cocaine reinforcement. Similarly, hyperactivity following acute cocaine can be attenuated by pre-treatment with naloxone (Houdi et al., 1989; Kim et al., 1997). Data from our lab have shown that intracerebroventricular (icv) administration of the selective mu opioid receptor antagonist, CTAP, significantly attenuates acute cocaine-induced hyperactivity and the development of sensitization and conditioned reward to cocaine (Schroeder et al., 2007). In addition, mu opioid receptor knockout mice display decreased cocaine self-administration (Mathon et al., 2005). All these data, taken together, suggest that the endogenous opioid system plays a role in cocaine-induced behaviors.

Perhaps the best characterized neuronal pathway involved in reward and locomotor activity is the mesolimbic dopamine system. This system is comprised of dopamine neurons with cell bodies in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the midbrain and projections to the limbic forebrain, including the nucleus accumbens, prefrontal cortex, and dorsal striatum. The nucleus accumbens is rich in both dopamine and opioid receptors (Tempel and Zukin, 1987; Wamsley et al, 1989) and cocaine administration has been shown to cause the release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens (Pettit and Justice, 1989). The VTA-nucleus accumbens pathway is a key detector of natural and drug rewarding stimuli. Dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens also modulate locomotor activity (Hooks et al., 1992).

Although data support the role of mu opioid receptors in modulating cocaine-induced locomotion and reward, the location of the mu opioid receptors involved has not been established. An evaluation of the effects of selective mu opioid receptor antagonists administered directly into specific brain regions on cocaine-induced behaviors is important for understanding how the endogenous opioid and dopaminergic systems interact to mediate the behavioral effects of cocaine. The present study sought to determine the contribution of mu opioid receptors in specific regions of the mesocorticolimbic system to the rewarding and locomotor-activating effects of cocaine in the rat. In addition, to further understand the role of mu opioid receptors in cocaine reward, neuronal activation was studied via cFos activation following the expression of cocaine-induced place preference.

Materials and Methods

Drugs

Cocaine HCl was generously provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, dissolved in sterile saline, and injected intraperitoneally (ip) in a dose of 10 mg/kg and a volume of 1 ml/kg body weight. The dose is based on the weight of the salt. D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr (CTAP) was obtained from Sigma, dissolved in sterile saline, and 0.5µg in 0.5 µl was administered bilaterally into the brain regions of interest.

Animals and surgery

All animal procedures were approved by Temple University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed guidelines set forth in the NIH’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male Sprague Dawley rats (approximately 60 days old) were obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Raleigh, NC), maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on 6 AM), and had ad libitum access to standard food and water. Approximately five days after arrival at our facility, animals underwent surgery for placement of two chronic indwelling 22GA cannula. Rats were anesthetized with Telazol (Fort Dodge Animal Health; tiletamine 20 mg/kg + zolazepam 20 mg/kg ip) and placed into a stereotaxic frame. The skull was exposed and two individual 22GA cannula were inserted bilaterally into the nucleus accumbens core or medial shell, caudate putamen, rostral VTA or caudal VTA (1.0 mm above the intended site of injection). Coordinates from bregma: nucleus accumbens core=A/P +1.7, M/L +/− 1.5, D/V −6.0, medial nucleus accumbens Shell=A/P +1.7, M/L +/− 0.6, D/V −6.0, caudate putamen= A/P +1.7, M/L +/− 1.5, D/V −4.5, rVTA= A/P −5.0, M/L +/− 1.6, D/V −8.0 at 6° towards midline and cVTA= A/P −6.04, M/L +/− 0.7, D/V −8.0 and were determined according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1986). The cannula were secured to the skull with dental acrylic anchored to a stainless steel surgical screw inserted into the skull. Stainless steel stylets, 1.0 mm longer than the guide cannulas, were inserted into the guide cannulas to keep them free of debris. Animals were allowed to recover from surgery for five days prior to the start of the experiment. Cannula placements were verified at the conclusion of the experiment.

Effect of CTAP on the Development of Conditioned Place Preference

Five days following implantation of bilateral cannula, drug administration and conditioning began. Conditioning chambers consisted of a 20 × 20 × 42 cm plexiglas chamber divided into two distinct compartments by a partition containing a removable door. One compartment had white walls with one inch wide vertical black stripes and a wire mesh floor. The opposite compartment had black walls and a smooth white floor. An unbiased counterbalanced conditioning paradigm was used to assess conditioned place preference. Conditioning occurred on days 1–4 of the procedure. Animals received identical treatments on days 1 and 3 and were confined to one side of the chamber and on days 2 and 4 and confined to the other side of the chamber. The order of drug and saline exposure days was counterbalanced for each condition and animals were randomly assigned to receive drug in either the black or striped side. Animals were divided into four groups (N=6–10 per treatment group; intracranial/ip): saline/saline, saline/cocaine, CTAP/cocaine or CTAP/saline. All rats received bilateral cannula injections (saline 0.5 µl/side or CTAP 0.5 µg/0.5 µl/side) in their home cage 20 minutes prior to an ip injection (saline 1 ml/kg or cocaine 10 mg/kg). Animals were placed into the conditioning chamber immediately following the ip injection for 30 minutes. Testing occurred on day 5 during which rats were allowed to freely explore both sides of the chamber in a drug-free state for 30 minutes, and the time spent in each side was recorded. The difference in seconds between the time spent in the drug-paired compartment and the saline-paired compartment was determined.

Activity Measurement

Activity was measured using a Digiscan D Micro System (Accuscan, Columbus, OH). Each activity monitor consists of an aluminum frame equipped with 16 infrared light beams and detectors. As the animal moves about the chamber, the beams are broken and recorded by a computer interfaced to the monitors. Thus, total activity counts reflect ambulatory activity, as well as rearing, grooming and stereotypy. Activity was measured within the conditioning chambers on day 1 as described above. Activity was recorded and tallied in five-minute bins for 30 minutes following the ip injection of either cocaine (10 mg/kg) or saline. Mean ± SD activity counts were calculated for the total 30 minute test period for each treatment group on day 1 of the study (N=6–10 per treatment group).

Effect of CTAP on the Expression of Conditioned Place Preference

Condition place preference was assessed as stated above with the following differences. Animals were divided into four groups (N=6 per treatment group). All rats received bilateral injections of saline (0.5 µl/side) into either the nucleus accumbens core or shell on days 1–4 in their home cage 20 minutes prior to an ip injection of saline (1 ml/kg) or cocaine (10 mg/kg). Animals were placed into the conditioning chamber immediately following the ip injection for 30 minutes. On day 5, twenty minutes prior to the test for place preference, animals received bilateral injections of either CTAP (0.5 µg/0.5 µl/side) or saline (0.5 µl/side) into the core or shell of the nucleus accumbens and were returned to their home cages. Twenty minutes after the intracranial injections, animals were placed in the conditioning chambers and were allowed to freely explore both sides of the chamber for 30 minutes. The time spent in each side was recorded. The difference in seconds between the time spent in the drug-paired compartment and the saline-paired compartment was determined.

cFos Immunohistochemistry

cFos was measured in the brains from animals used in the study of the nucleus accumbens core in the establishment of cocaine conditioned place preference. Ninety minutes post-testing for conditioned place preference, four animals/group were anesthetized with Telazol 40 mg/kg i.p. and perfused interventricularly with PBS + heparin (7 ml/min for 10 min) followed by 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) (7 ml/min for 10 min). Brains were removed and submerged in 10% NBF for 1 week at 4°C. Brains were then dehydrated (70% EtOH 1h, 80% EtOH 1h, 95% EtOH 1h, 95% EtOH 1h, 95% EtOH 1h, 100% EtOH 1h, 100% EtOH 1h, 100% EtOH 1h, xylene 45 min, xylene 45 min, paraffin 30 min, paraffin 30 min, paraffin 1h, paraffin 1h) and embedded in paraffin for sectioning. Five µM coronal sections were made throughout the brain regions of interest and adhered to slides for immunohistochemistry.

Sections were incubated at 60°C overnight to initiate the paraffin removal and then rehydrated (xylene 5 min, xylene 5 min, 100% EtOH 3 min, 100% EtOH 2 min, 95% EtOH 2 min, H2O 5 min). Antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer (pH 7.1) with incubation in a decloaking apparatus (22 PSI 30 seconds 127°C, Atm pressure 10 seconds) and then cooled to room temperature over 20 minutes. Sections were rinsed for 5 minutes in water and then stained for cFos expression.

Sections were stained using a Dako autostainer under the following conditions: 10 min peroxide block, 20 min incubation in normal goat serum block, 30 minute power block (Biogenex), 1 hour incubation with primary antibody (Calbiochem PC05 1:20), 1 hour incubation with the secondary antibody (Chemicon AP132B 1:500), 30 minute incubation with Vectastain ABC and a 10 minute DAB incubation. cFos positive cells were counted within the nucleus accumbens, motor cortex, prefrontal cortex, caudate putamen, basolateral amygdala, ventral pallidum, VTA and olfactory nucleus for the four treatment groups. cFos positive nuclei were counted from six sections for each brain region from each animal. Total number of cFos positive cells from the six sections was determined for each animal. Group means and standard deviations were calculated from four animals per treatment group.

Data Analysis

All data were analyzed by two-way ANOVAs with pre-treatment and treatment factors. Bonferroni’s post-hoc analysis was performed after significance was determined by ANOVA (Graphpad Prism V.4). The null hypothesis was rejected when p<0.05.

Results

Effect of CTAP on the Development of Conditioned Place Preference

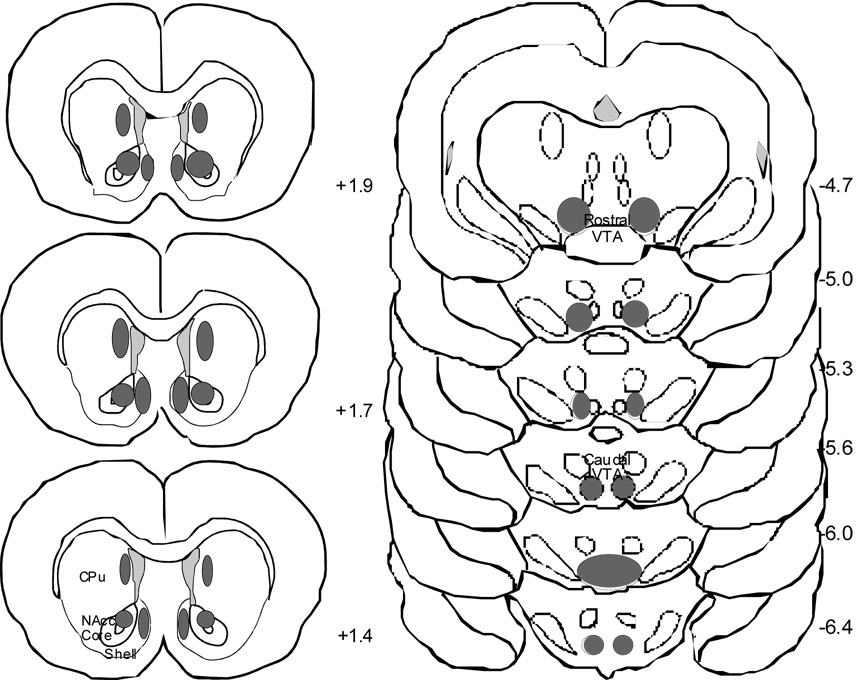

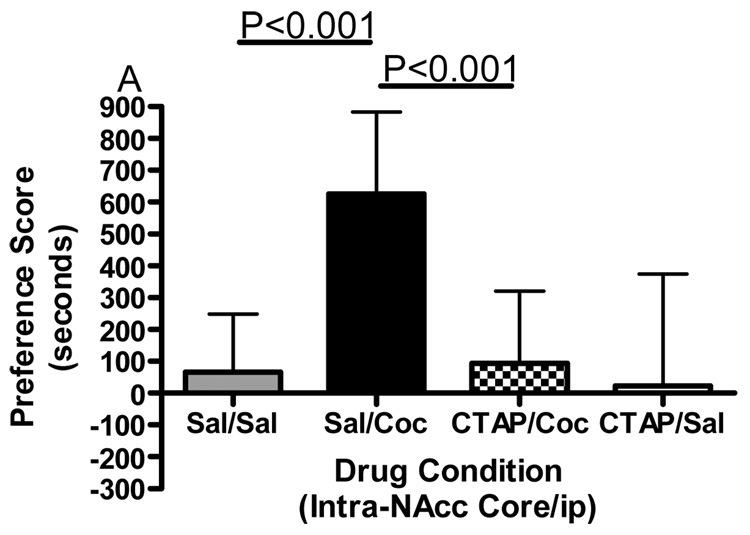

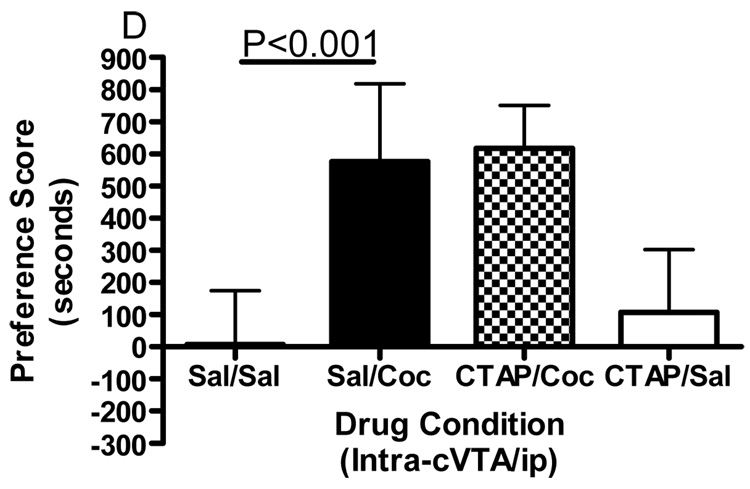

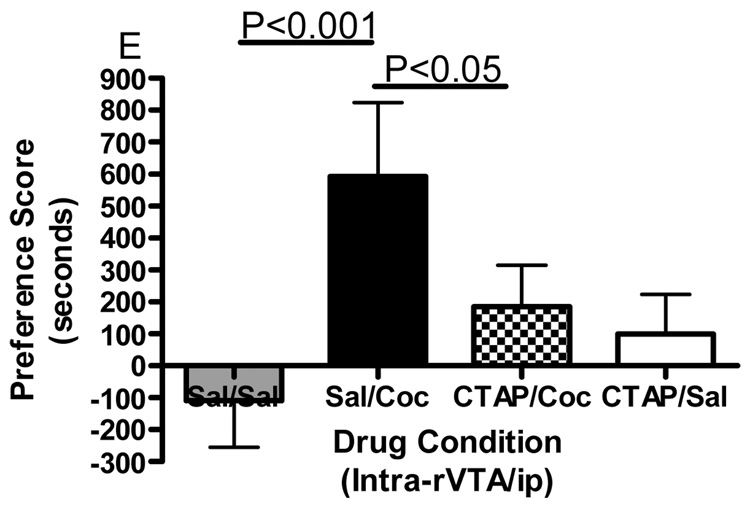

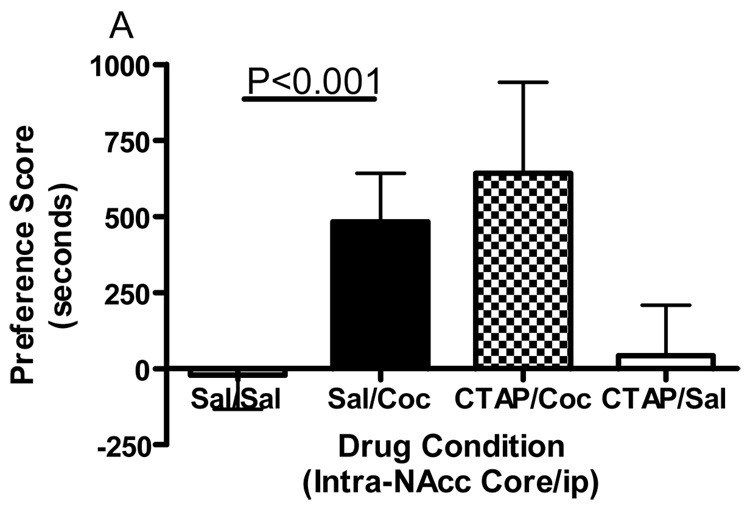

Conditioned place preference together with microinjections of the selective mu opioid receptor antagonist CTAP into five specific brain regions was employed to evaluate the role of mu opioid receptors within these regions in the development of cocaine reward. Figure 1 shows termination sites of the tracts from the injection cannula for all regions studied. The data displayed in Fig. 2 represent the mean (± SD) in preference for the drug-paired environment for each of the five separate brain regions tested. CTAP administered directly into the core of the nucleus accumbens attenuated the development of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (Fig. 2A). Two-way ANOVA revealed significant treatment, pre-treatment and interaction effects (Interaction:F(1,33)=7.909, p=0.0082; Pre-treatment:F(1,33)=10.97, p=0.0023; Treatment:F(1,33)=13.17, p=0.001). Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that CTAP administered into the nucleus accumbens core significantly attenuated the development of a preference for a cocaine-paired environment (sal/coc vs CTAP/coc = p<0.001). Injections of CTAP into the shell of the nucleus accumbens had no significant effect on the development of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (Fig. 2B). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference between groups (Interaction:F(1,20)=2.356, p=0.1405; Pre-treatment: F(1,20)=0.011, p=0.9179; Treatment:F(1,20)=91.76, p<0.0001). Although cocaine produced a significant place preference, CTAP did not attenuate the development of a preference for a cocaine-paired environment (post-test: sal/coc vs CTAP/coc = p>0.05). CTAP administered into the caudate putamen did not affect cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (Fig. 2C). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference between groups (Interaction:F(1,20)=0.057, p=0.8132; Pre-treatment:F(1,20)=0.1911, p=0.6667; Treatment:F(1,20)=70.02, p<0.0001). Although cocaine produced a significant place preference, CTAP into the caudate putamen did not attenuate the development of a preference for a cocaine-paired environment (post-test: sal/coc vs CTAP/coc = p>0.05). Pre-treatment with CTAP into the caudal aspect of the VTA had no significant effect on cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (Fig. 2D). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference between groups (Interaction:F(1,20)=0.1476, p=0.7049; Pre-treatment:F(1,20)=0.832, p=0.3725; Treatment:F(1,20)=48.97, p<0.0001). Again, cocaine produced a significant place preference, although CTAP did not attenuate the development of a preference for a cocaine-paired environment when injected into the caudal VTA (sal/coc vs CTAP/coc = p>0.05). However, pre-treatment of CTAP into the rostral VTA significantly attenuated cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (Fig. 2E). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference between groups (Interaction:F(1,22)=9.516, p=0.0054; Pre-treatment:F(1,22)=1.001, p=0.3280; Treatment:F(1,22)=15.56, p<0.001). Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that intra-rostral VTA CTAP significantly attenuated the development of preference for a cocaine-paired environment (sal/coc vs CTAP/coc = p<0.05). Administration of CTAP plus ip saline (CTAP/sal) did not produce a significant place preference or place aversion in any of the five brain regions studied (one sample t-test against zero: = p>0.05 for all brain regions) and was not significantly different from saline (two-way ANOVA: CTAP/sal vs sal/sal = p>0.05 for all brain regions). These data indicate that blockade of mu opioid receptors within the nucleus accumbens core or rostral aspect of the VTA prior to conditioning with cocaine attenuated the development of cocaine-induced reward.

Figure 1.

Injection sites are plotted on coronal brain sections for rats that received intracranial injections of CTAP or saline. The deepest penetration of the cannula track for all animals fell within the darkened ovals. The distance of each section from bregma is given in millimeters (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). Nucleus NAcc=nucleus accumbens; VTA=ventral tegmental area; CPu=caudate putamen.

Figure 2.

Effect of CTAP on the development of cocaine-induced place preference. Animals received CTAP (0.5 µg/0.5 ul) or saline (0.5 ul) bilaterally through injection cannula prior to cocaine (10 mg/kg ip) or saline (1 ml/kg ip) in a conditioned place preference procedure. CTAP was injected into the NAcc core (2A), NAcc shell (2B), CPu (2C), caudal VTA (2D) or rostral VTA (2E). Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that CTAP significantly attenuated the preference for a cocaine-paired environment when injected into the NAcc core (P<0.001) or rostral VTA (P<0.05). Neither CTAP alone nor saline alone produced a place preference or place aversion, and both were significantly different from cocaine [CTAP/sal or sal/sal versus sal/coc: p<0.001]. Data are presented as mean (± SD) in seconds spent in the drug-paired chamber minus the saline paired chamber (N=8–12/group).

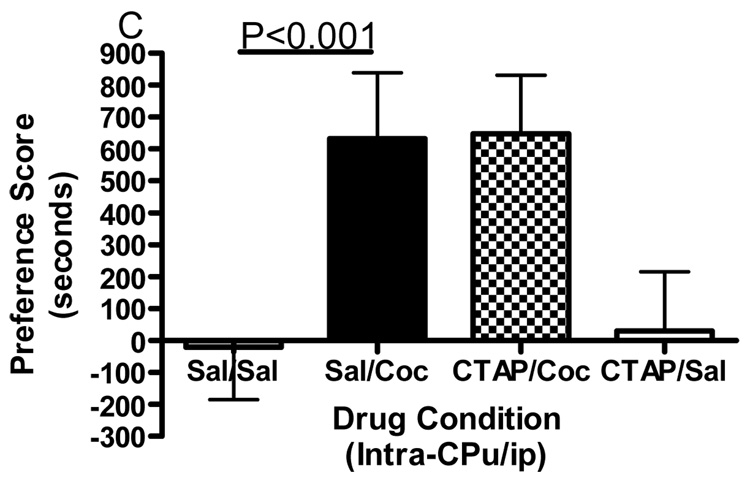

Effect of CTAP on Cocaine-Induced Hyperactivity

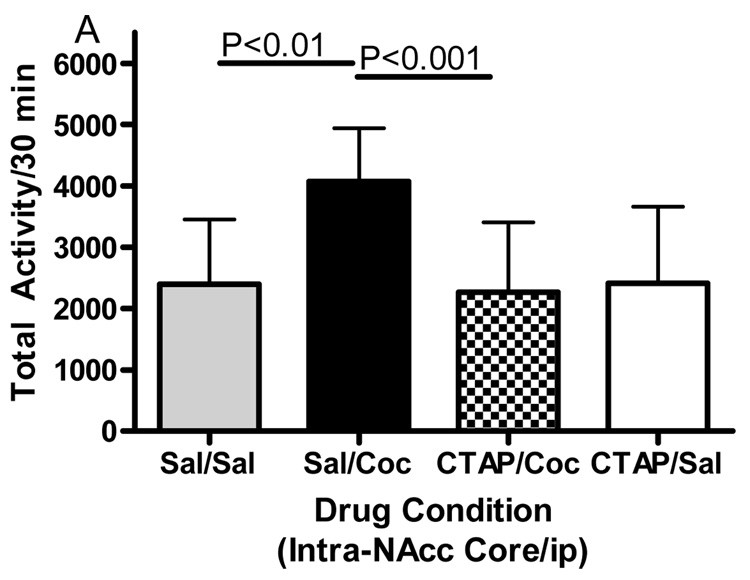

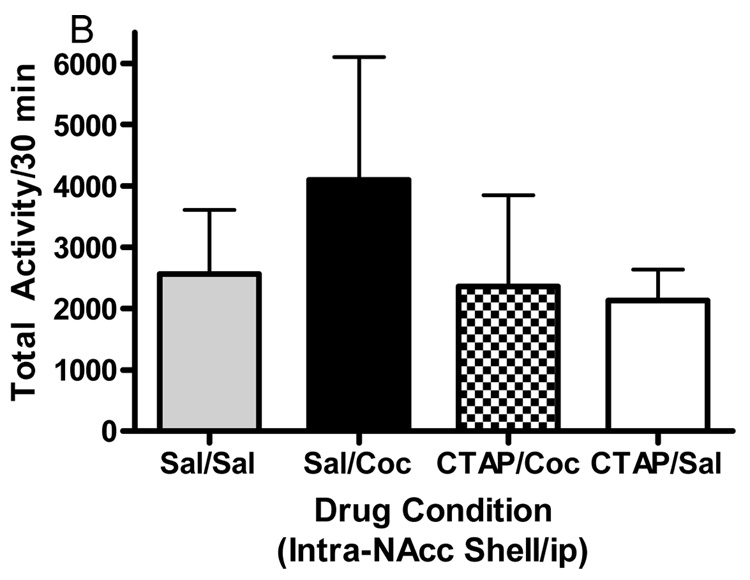

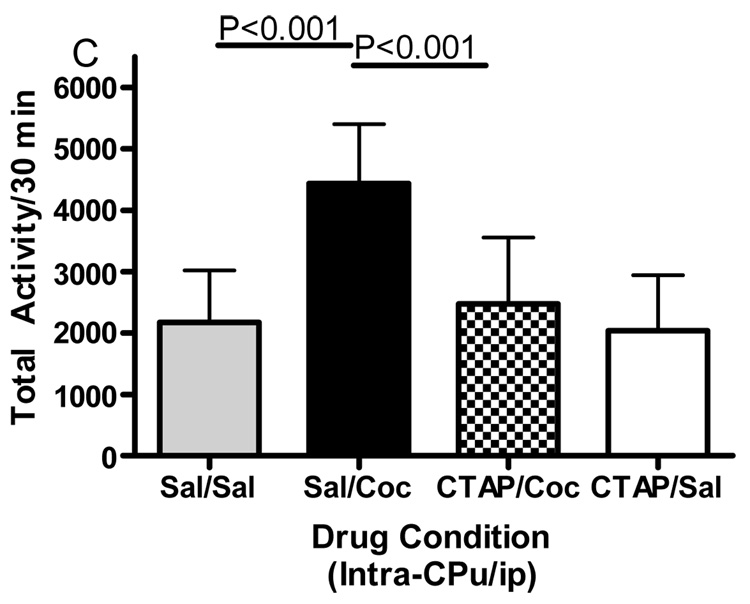

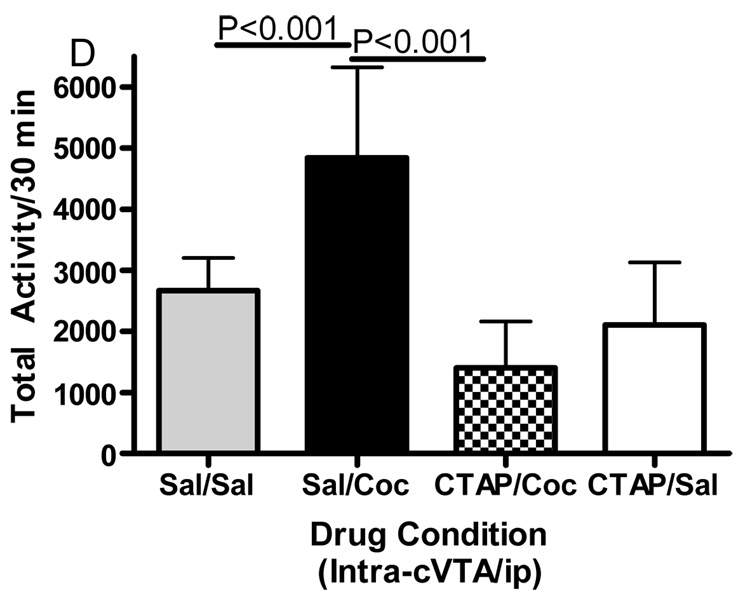

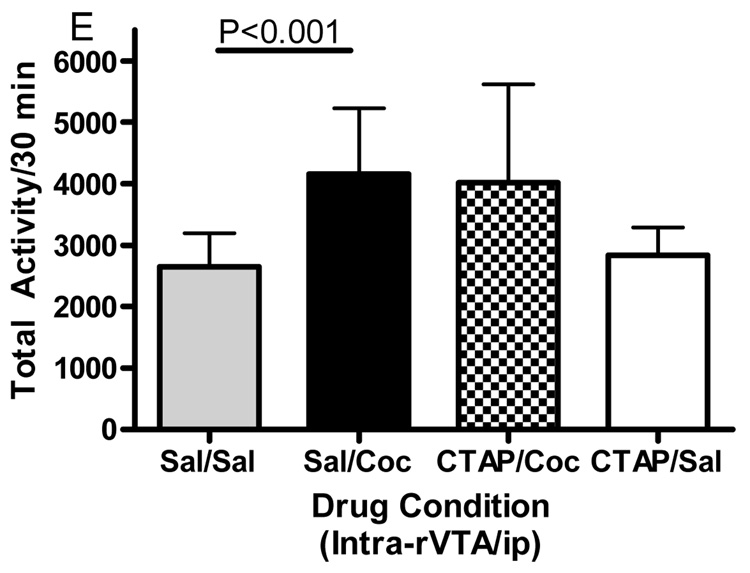

Microinjections of the selective mu opioid receptor antagonist CTAP into five brain regions was employed to evaluate the role of mu opioid receptors in cocaine-induced hyperactivity. The data displayed in Fig. 3 represent the mean (± SD) activity counts for animals in each experimental group. CTAP pretreatment into the nucleus accumbens core, caudate putamen or caudal VTA significantly attenuated cocaine-induced hyperactivity. For the core of the nucleus accumbens (Fig. 3A), two-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference between groups (Interaction:F(1,32)=6.362, p<0.05; Pre-treatment:F(1,32)=6.195, p<0.05; Treatment:F(1,32)=4.433, p<0.05). Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that CTAP injected into the core of the nucleus accumbens significantly attenuated cocaine-induced hyperactivity (sal/coc vs CTAP/coc = p<0.001). For the medial shell of the nucleus accumbens (Fig. 3B), two-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference between groups (Interaction:F(1,27)=1.572, p>0.05; Pre-treatment:F(1,27)=4.306, p<0.05; Treatment:F(1,27)=2.822, p>0.05). Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that CTAP injected into the shell of the nucleus accumbens did not attenuate cocaine-induced hyperactivity (sal/coc vs CTAP/coc = p>0.05). For the caudate putamen (Fig. 3C), two-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference between groups (Interaction:F(1,28)=7.052, p<0.05; Pre-treatment:F(1,28)=9.258, p<0.01; Treatment:F(1,28)=15.30, p<0.001). Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that CTAP injected into the caudate putamen significantly attenuated cocaine-induced hyperactivity (sal/coc vs CTAP/coc = p<0.001). For the caudal VTA (Fig. 3D), two-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference between groups (Interaction:F(1,27)=14.50, p<0.001; Pre-treatment:F(1,27)=28.04, p<0.0001; Treatment:F(1,27)=3.734, p>0.05). Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that CTAP injected into the caudal VTA significantly attenuated cocaine-induced hyperactivity (sal/coc vs CTAP/coc = p<0.001). For the rostral aspect of the VTA (Fig. 3E), ANOVA revealed a significant difference between groups (Interaction:F(1,27)=0.2031, p>0.05; Pre-treatment: F(1,27)=0.0042, p>0.05; Treatment:F(1,27)=14.01, p<0.001). Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that CTAP injected into the rostral VTA did not attenuate cocaine-induced hyperactivity (sal/coc vs CTAP/coc = p>0.05). Administration of CTAP plus i.p. saline (CTAP/sal) in any of the five brain regions studied did not alter total activity. These data indicate that blockade of mu opioid receptors within the nucleus accumbens core, caudate putamen or caudal region of the VTA prior to cocaine attenuated cocaine-induced hyperactivity.

Figure 3.

Effect of CTAP on cocaine-induced hyperactivity. Animals received CTAP (0.5 µg/0.5 ul) or saline bilaterally through injection cannula prior to cocaine (10 mg/kg ip) or saline (1 ml/kg ip) and total activity counts were recorded for 30 minutes. CTAP was injected into the NAcc core (3A), NAcc shell (3B), CPu (3C), caudal VTA (3D) or rostral VTA (3E). Two-way ANOVA with pre-treatment and treatment as factors revealed that CTAP significantly attenuated cocaine-induced hyperactivity when injected into the NAcc core (P<0.001), caudate putamen (P<0.001) or caudal VTA (P<0.001). CTAP alone was not significantly different from saline [CTAP/sal versus sal/sal: p>0.05] for any group tested. Data are presented as mean (± SD) for the total activity from the locomotor session (N=6–10/group).

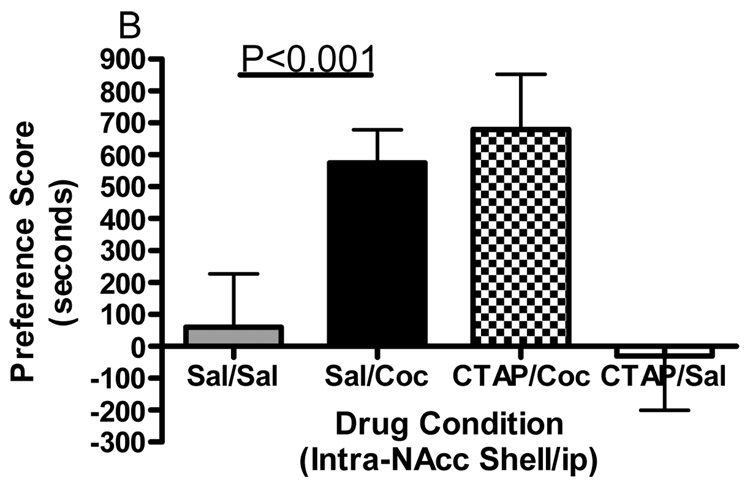

Effect of CTAP on the Expression of Cocaine Place Preference

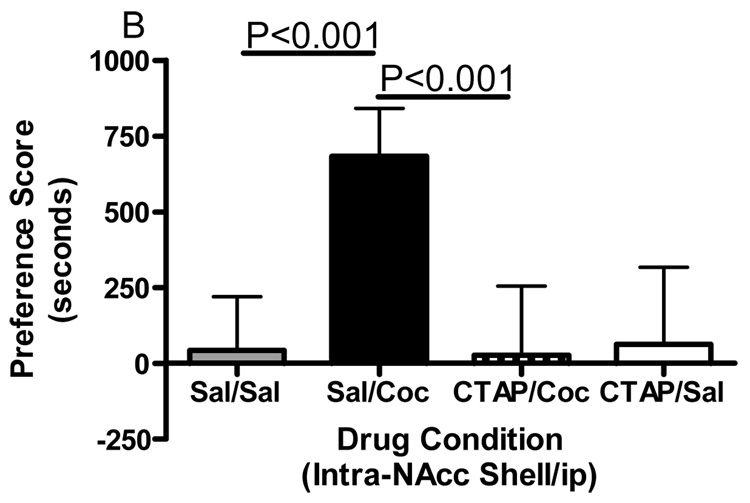

The importance of mu opioid receptors within the nucleus accumbens core and shell in the expression of cocaine reward was investigated. Animals were conditioned with cocaine and 20 minutes prior to the test for expression of conditioned place preference CTAP or saline was administered into either the core or medial shell of the nucleus accumbens and preference determined. Animals conditioned with cocaine and receiving saline into the core of the nucleus accumbens 20 minutes prior to the expression of conditioned place preference showed a significant place preference (Fig. 4A). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant treatment effect (Interaction:F(1,30)=0.4857, p=0.4912; Pre-treatment:F(1,30)=2.626, p=0.1156; Treatment:F(1,30)=64.47, p<0.0001). Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that CTAP into the nucleus accumbens core did not attenuate the expression of a preference for a cocaine-paired environment (sal/coc vs CTAP/coc = p>0.05). However, CTAP injected into the nucleus accumbens shell significantly attenuated the expression of cocaine place preference (Fig. 4B). Two-way ANOVA revealed significant treatment, pre-treatment and interaction factors (Interaction:F(1,20)=15.85, p=0.0007; Pre-treatment:F(1,20)=14.12, p=0.0012; Treatment:F(1,20)=12.68, p=0.002; Bonferroni post-hoc: sal/coc vs CTAP/coc = p<0.001). These data indicate that mu opioid receptors within the nucleus accumbens shell but not the core are important for the expression of a cocaine place preference.

Figure 4.

Effect of CTAP on expression of cocaine-induced place preference. Animals received CTAP (0.5 µg/0.5 ul) or saline (0.5ul) bilaterally through injection cannula prior to testing for expression of cocaine-induced place preference. CTAP was injected into the NAcc core (4A) or NAcc shell (4B) 20 minutes prior to the test for expression of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that CTAP significantly attenuated the preference for a cocaine-paired environment when injected into the NAcc shell (P<0.001). Data are presented mean (± SD) seconds spent in the drug-paired chamber minus the saline paired chamber (N=6–8/group).

cFos Immunohistochemistry

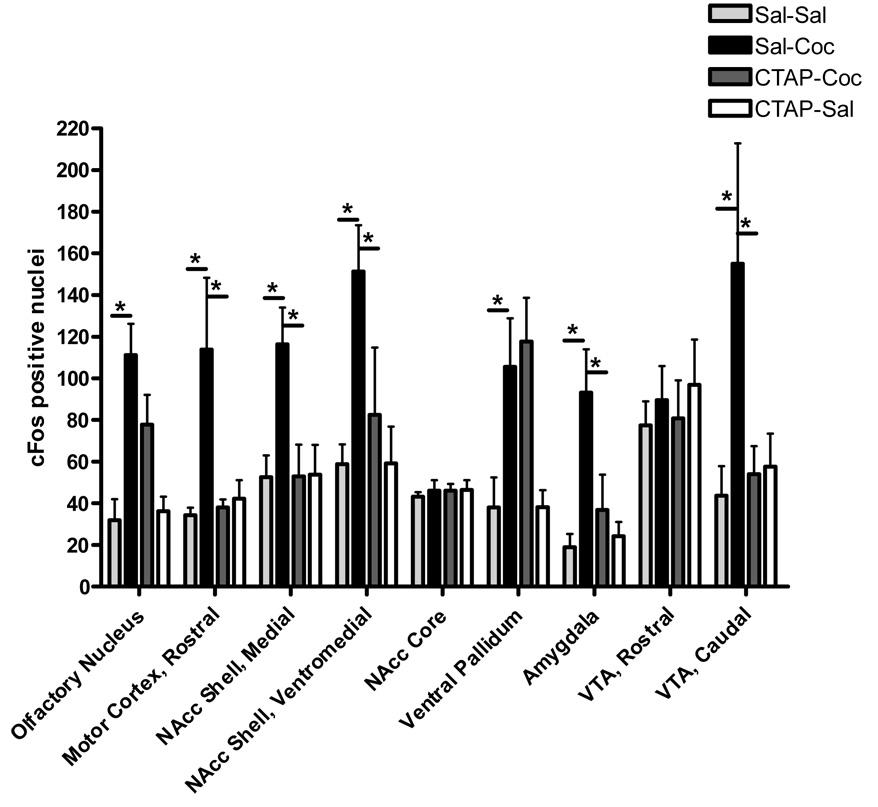

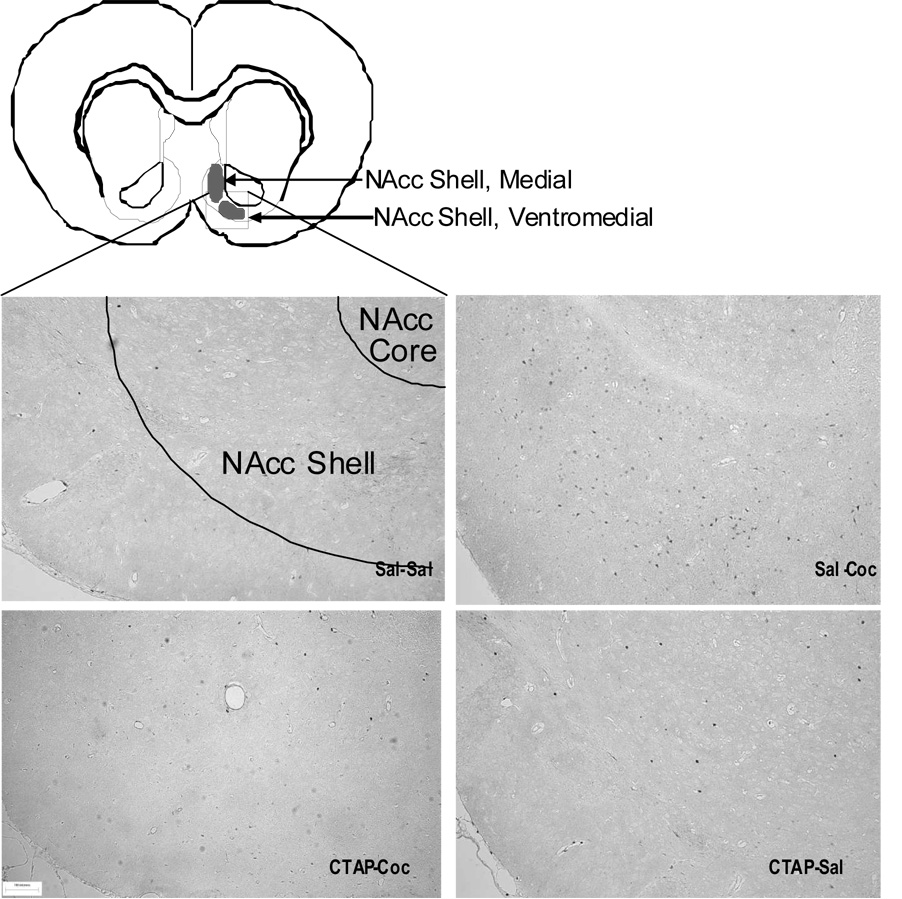

cFos immunoreactivity was measured to determine the brain regions that are activated during the expression of cocaine place preference and to determine whether neuronal activation is blocked by a mu opioid receptor antagonist given into the nucleus accumbens core during conditioning with cocaine. Expression of cocaine-place preference was accompanied by a significant increase in cFos positive nuclei within the olfactory nucleus, rostral motor cortex, medial nucleus accumbens shell, ventromedial nucleus accumbens shell, ventral pallidum, basolateral amygdala, and caudal VTA (Figure 5). Two-way ANOVA show a significant difference between treatment groups within these seven brain regions (Treatment: p<0.005 for all regions; Interaction: p<0.01 for all regions except VP p=0.51; Pre-treatment: p<0.05 for all regions except the VP p=0.50; Post-hoc: sal/sal vs sal/coc p<0.001 for all seven regions). Pretreatment with CTAP during conditioning prevented the increase in cFos positive nuclei within the rostral motor cortex, medial nucleus accumbens shell, ventromedial nucleus accumbens shell, basolateral amygdala and caudal VTA (sal/coc vs CTAP/coc, p<0.001for all regions). Staining for cFos positive nuclei within the ventromedial aspect of the nucleus accumbens shell for the four treatment groups is shown in Figure 6. The number of cFos-positive nuclei was not increased in the nucleus accumbens core, caudal motor cortex, rostral caudate putamen, rostral hippocampus or caudal hippocampus during the expression of cocaine place preference (Figure 5 and Table 1). These data indicate that expression of cocaine-induced reward activates neurons in the nucleus accumbens shell, motor cortex, basolateral amygdala, caudal VTA, ventral pallidum and olfactory nucleus, regions shown to be involved in reward and memory.

Figure 5.

Data are expressed as mean (± SD) of cFos positive nuclei per brain region. Animals were injected with CTAP (0.5 ug/0.5 ul) or saline (0.5 ul) into the nucleus accumbens core prior to saline (CTAP-sal or sal-sal) or cocaine (CTAP-coc or sal-coc) conditioning. Animals were euthanized ninety minutes following the test for expression of place preference, and brains removed and prepared for analysis. Two-way ANOVA shows a significant increase in cFos positive nuclei in the olfactory nucleus, rostral motor cortex, medial NAcc shell, ventromedial NAcc shell, ventral pallidum, basolateral amygdala, and caudal VTA (p<0.001 for all regions) in cocaine conditioned animals. cFos induction was significantly attenuated within the rostral motor cortex, NAcc shell, amygdada and caudal VTA in animals pretreated with CTAP during conditioning (p<0.001 for all regions).

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs illustrating the distribution of cFos positive nuclei within the ventromedial nucleus accumbens shell 90 minutes after the test for expression of cocaine place preference. Photomicrographs taken from the ventromedial nucleus accumbens shell A/P +1.68 (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). Regions of cFos quantitation within the medial and ventromedial NAcc shell are highlighted with darkened ovals in the illustration. The square outline on the illustration shows the region where the photomicrographs were taken. Bar indicates 10 µM.

Table 1.

Data are expressed as mean (±SD) of cFos positive nuclei 90 minutes following the test for expression of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Animals were injected with CTAP (0.5 ug/0.5 ul) or saline (0.5 ul) into the nucleus accumbens core prior to saline (CTAP-sal or sal-sal) or cocaine (CTAP-coc or sal-coc) during the conditioning days. Two-way ANOVA show no significant differences in cFos positive nuclei in any region listed. (N=4/group)

| Sal-Sal | Sal-Coc | CTAP-Coc | CTAP-Sal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | |

| Caudal Motor Cortex | 81 | 18.4 | 69.5 | 25.1 | 72.5 | 28.3 | 70.9 | 25.1 |

| Rostral Caudate Putamen | 35 | 18.2 | 24.5 | 8.2 | 30.3 | 4.6 | 34.4 | 18.2 |

| Caudal Caudate Putamen | 12.5 | 2.6 | 18.2 | 8.6 | 15.1 | 2.9 | 18.7 | 3.5 |

| Rostral Hippocampus | 24.1 | 3.6 | 26.3 | 1.2 | 31.2 | 5.7 | 27.8 | 4.1 |

| Caudal Hippocampus | 124.9 | 12.4 | 151.4 | 48.4 | 98.1 | 35.7 | 121.7 | 9.8 |

Discussion

Previous studies using non-selective opioid receptor antagonists have shown that the opioid system plays a role in cocaine-induced reward (Bain and Kornetsky, 1987; Corrigall and Coen, 1991; Bilsky et al., 1992) and hyperlocomotion (Houdi et al., 1989, Kim et al., 1997). In addition, a recent study by our lab has demonstrated that icv administration of the selective mu opioid receptor antagonist CTAP significantly attenuated acute cocaine-induced hyperactivity, and the development of sensitization and conditioned reward to cocaine (Schroeder et al., 2007). In the present study, we identify the anatomical loci within the mesocorticolimbic pathway where mu opioid receptors modulate cocaine-induced reward and hyperactivity.

The VTA can be divided into rostral and caudal regions based on cell types and neuronal connections. The caudal VTA has a higher proportion of dopamine containing neurons, where as the rostral VTA has a higher proportion of GABAergic interneurons (Johnson and North, 1992b). Recent data have also suggested functional heterogeneity within the VTA. For example, rats will self-administer the GABAA receptor antagonist picrotoxin into the rostral but not caudal VTA (Ikemoto et al., 1997b). This blockade of rostral GABAA receptors results in an increase in dopamine outflow in the nucleus accumbens as measured by microdialysis (Ikemoto et al., 1997a). Similarly, heroin or morphine injections into the rostral VTA are rewarding as shown by conditioned place preference (Olmstead and Franklin, 1997) and animals will self-administer morphine, the selective mu opioid receptor agonist DAMGO or cocaine into the rostral VTA (Devine and Wise, 1994). Our results also demonstrate functional differences between the rostral and caudal aspects of the VTA. In assessing the impact of mu opioid receptor blockade on the development of cocaine place preference, rats receiving bilateral injections of CTAP into the rostral VTA but not the caudal VTA prior to cocaine during the conditioning sessions, show a significant attenuation of cocaine-induced place preference. These data agree with previous studies demonstrating that the non-selective opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone administered into the rostral VTA attenuates cocaine self-administration (Ramsey et al., 1999), and extends those findings to indicate that specifically mu opioid receptors within the rostral VTA play an important role in the development of cocaine place preference.

Dopamine neurons within the VTA project to the nucleus accumbens and this mesolimbic dopamine system is a critical component of the endogenous reward circuitry. The nucleus accumbens can be subdivided into core and shell subregions based on neuronal connections and cell populations. Intravenous cocaine increases dopamine in the nucleus accumbens shell to a greater degree than in the core (Pontieri et al., 1995). The shell receives glutamatergic input from the hippocampus, amygdala and prefrontal cortex (Heimer et al., 1997). The core of the nucleus accumbens has a high proportion of GABAergic medium spiny neurons that project to the VTA (Kalivas et al, 1993). The results of the present study demonstrate that mu receptors in the core and the shell of the nucleus accumbens are selectively important for the development and expression of cocaine place preference respectively. Bilateral injections of CTAP into the nucleus accumbens core but not the shell prior to cocaine during conditioning significantly attenuated the development of cocaine-induced place preference. Blockade of mu opioid receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell, but not the core, blocked the expression of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference.

Our current results can be explained by the hypothesis that cocaine causes the release of endogenous opioid peptides that activate mu opioid receptors in the nucleus accumbens and VTA. Previous studies have demonstrated that cocaine can cause the release of endogenous opioids (Moldow and Fischman, 1987; Olive et al., 2001; Roth-Deri et al., 2003). Mu opioid receptors are located on medium spiny neurons in the accumbens and on GABAergic interneurons in the VTA (Johnson and North, 1992a). Activation of mu opioid receptors inhibits GABA release in the VTA, thus disinhibiting mesolimbic dopamine neurons and increasing dopamine outflow in the nucleus accumbens. The current data suggest that cocaine causes the release of endogenous opioids within the nucleus accumbens and rostral VTA. These opioids may activate the mu opioid receptors on GABAergic neurons causing the disinhibition of VTA dopamine neurons. This, in turn could increase dopamine outflow throughout the mesocorticolimbic pathway, which is rewarding. Thus, endogenous opioids acting on mu opioid receptors within the nucleus accumbens core and rostral VTA are important for the development of reward and the learned association between the rewarding aspects of cocaine and the environment. Mu opioid receptors within the shell of the nucleus accumbens are not necessary for the development of cocaine-induced place preference, but are necessary for the expression of this preference. This may be due to the shift from nucleus accumbens core-dependent establishment of behaviors to nucleus accumbens shell directed stimulus-response habits and may increasingly involve inputs from the hippocampus, amygdala and prefrontal cortex into the shell of the nucleus accumbens.

The sites of neuronal activation within the mesocorticolimbic system during the expression of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference were also investigated using cFos as a marker of neuronal activation. Previous studies have shown that animals conditioned with cocaine show elevated levels of cFos in the prelimbic cortex, basolateral amygdala complex and nucleus accumbens core but not the central amygdala, caudate putamen or infralimbic cortex (Miller and Marshall, 2004). The present study showed an increase in cFos positive nuclei in the ventromedial and medial aspects of the nucleus accumbens shell, motor cortex, olfactory nucleus, ventral pallidum, basolateral amygdala, and caudal VTA in animals conditioned with cocaine as compared with saline-injected controls. Our finding that exposure to a cocaine-paired environment increased cFos expression in the ventromedial and medial nucleus accumbens shell, olfactory nucleus, motor cortex, basolateral amygdala, caudal VTA and ventral pallidum is supported by a large body of evidence indicating that these regions are involved in cocaine seeking (Brown et al., 1992; Crawford et al., 1995; Neisewander et al., 2000). The current data confirm and add to previous findings. The ability of CTAP administered into the medial nucleus accumbens shell to block expression of cocaine-induced place preference in this study also supports the finding that neurons within the shell region of the nucleus accumbens are activated during the expression of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference.

The present results also demonstrated that pretreatment with CTAP in the nucleus accumbens core during cocaine conditioning prevented the development of a cocaine place preference and blunted cFos elevation in all of these areas with the exception of the ventral pallidum and olfactory nucleus. The medial and lateral shell of the accumbens project to the ventromedial and ventrolateral part of the ventral pallidum, respectively (Zahm and Heimer, 1990; Heimer et al., 1991). These projections to the ventral pallidum are GABAergic and primarily co-localize with enkephalin (Zahm et al., 1985). Previous studies have shown that blockade of mu opioid receptors in the ventral pallidum prevent the acquisition of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (Skoubis and Maidment, 2003) and block reinstatement of active lever pressing by cocaine (Tang et al., 2005). Our finding that blockade of mu opioid receptors in the nucleus accumbens core during cocaine conditioning did not attenuate cFos elevation within the ventral pallidum during the expression of place preference may be due to either the concentration of CTAP used or the site of administration. The prefrontal cortex, including the olfactory nucleus contain afferents from numerous locations including the VTA, amygdala and dorsal thalamus (Alexander et al., 1990; Kalivas and Nakamura, 1999) and the prefrontal cortex sends efferents to the nucleus accumbens (Heimer et al., 1997). These data give support for the finding that mu opioid receptor blockade within the core during cocaine conditioning had no effect on neuronal activation within the olfactory nucleus during the expression of cocaine place preference.

The mu opioid receptor antagonist attenuated the locomotor-stimulating effects of cocaine when administered into either the nucleus accumbens core, caudate putamen or caudal VTA, demonstrating a role of mu opioid receptors specifically within these brain regions in cocaine-induced hyperactivity. Previous studies have shown that morphine and DAMGO administered into the caudal VTA induces hyperlocomotion in the rat (Joyce and Iversen, 1979), likely by increasing dopamine outflow. This supports the hypothesis that cocaine is causing the release of opioids in the caudal VTA which in turn facilitates the hyperlocomotion response.

The present results also demonstrate that blockade of mu opioid receptors in the nucleus accumbens core can attenuate cocaine-induced hyperlocomotion. The specificity of the nucleus accumbens core over the shell in this regard agrees with previous findings that the accumbens core, but not the shell, contributes to the behavioral activation produced by amphetamine (Sellings and Clarke, 2003). The other site of mu opioid receptor-mediated attenuation of cocaine locomotion in this study is the caudate putamen. The caudate putamen has been shown to be important for locomotor activity in the rat. Blockade of dopamine D2 receptors in the caudate putamen reduces spontaneous locomotion in the rat (Hauber and Munkle, 1997). Further, lesions of the caudate putamen reduce hyperactivity produced by morphine (Siegfried et al., 1982).

In summary, the results of the present study demonstrate the importance of mu opioid receptors in cocaine-induced reward and activity, and demonstrate the anatomical selectivity of mu receptors within the nucleus accumbens, VTA and caudate putamen in this regard. These data suggest that cocaine causes the release of endogenous opioid peptides and that these peptides contribute to the rewarding and locomotor-stimulating effects of cocaine. Further, the data also suggest that opioid peptides are released in the nucleus accumbens shell during the expression of cocaine place preferences and that mu opioid receptors in this region are critical for the manifestation of this behavior. The question of which opioid peptide or peptides is involved has yet to be answered. It has been shown that acute administration of cocaine causes the release of endogenous endorphins (Moldow and Fischman, 1987; Olive et al., 2001; Roth-Deri et al., 2003). Our results provide strong evidence of a role specifically for mu opioid receptors within anatomically defined regions of the nucleus accumbens and VTA in cocaine-induced reward and activity in the rat.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH/NIDA R01 DA09580 (EMU). The authors would like to thank Peter Bugelski and Patricia Rafferty from Centocor Inc. Research and Development, for their expert guidance and training in immunohistochemistry.

ABBREVIATIONS

- NAcc

Nucleus Accumbens

- rVTA

Rostral Ventral Tegmental Area

- cVTA

Caudal Ventral Tegmental Area

- CPu

Caudate Putamen

- RMoCo

Rostral Motor Cortex

- mPFC

Medial Prefrontal Cortex

- CTAP

D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexander GE, Crutcher MD, DeLong MR. Basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits: parallel substrates for motor, oculomotor, “prefrontal” and “limbic” functions. Prog Brain Res. 1990;85:119–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain GT, Kornetsky C. Naloxone attenuation of the effect of cocaine on rewarding brain stimulation. Life Sci. 1987;40:1119–1125. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90575-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsky EJ, Montegut MJ, Delong CL, Reid LD. Opioidergic modulation of cocaine conditioned place preferences. Life Sci. 1992;50:PL85–PL90. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EE, Robertson GS, Fibiger HC. Evidence for conditional neuronal activation following exposure to a cocaine-paired environment: role of forebrain limbic structures. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4112–4121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-04112.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigall WA, Coen KM. Opiate antagonists reduce cocaine but not nicotine self-administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;104:167–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02244173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford CA, McDougall SA, Bolanos CA, Hall S, Berger SP. The effects of the kappa agonist U-50,488 on cocaine-induced conditioned and unconditioned behaviors and Fos immunoreactivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120:392–399. doi: 10.1007/BF02245810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine DP, Wise RA. Self-administration of morphine, DAMGO, and DPDPE into the ventral tegmental area of rats. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1978–1984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-01978.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink JS, Smith GP. Mesolimbicocortical dopamine terminal fields are necessary for normal locomotor and investigatory exploration in rats. Brain Res. 1980;199:359–384. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90695-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer RP., Jr. Cocaine alters opiate receptor binding in critical brain reward regions. Synapse. 1989;3:55–60. doi: 10.1002/syn.890030108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauber W, Munkle M. Motor depressant effects mediated by dopamine D2 and Adenosine A2A receptors in the nucleus accumbens and the caudate-putamen. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;323(2–3):127–131. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila RE, Orlansky H, Mytilineou C, Cohen G. Amphetamine: evaluation of d- and l-isomers as releasing agents and uptake inhibitors for 3H-dopamine and 3Hnorepinephrine in slices of rat neostriatum and cerebral cortex. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;194:47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L, Zahm DS, Churchill L, Kalivas PW, Wohltmann C. Specificity in the projection patterns of the accumbal core and shell in the rat. Neuroscience. 1991;41:89125. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90202-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L, Alheid GF, de Olmos JS, Groenwegen HJ, Haber SN, Harlan RE, Zahm DS. The accumbens: beyond the core-shell dichotomy. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9(3):354–381. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooks MS, Colvin AC, Juncos JL, Justice JB. Individual differences in basal and cocaine-stimulated extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens using quantitative microdialysis. Brain Res. 1992;587(2):306–312. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdi AA, Bardo MT, Van Loon GR. Opioid mediation of cocaine-induced hyperactivity and reinforcement. Brain Res. 1989;497:195–198. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90989-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd YL, Herkenham M. Molecular alterations in the neostriatum of human cocaine addicts. Synapse. 1993;13(4):357–369. doi: 10.1002/syn.890130408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Kohl RR, McBride WJ. GABAA receptor blockade in the anterior ventral tegmental area increases extracellular levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of rats. J Neurochem. 1997a;69:137–143. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69010137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Self infusion of GABAA antagonists directly into the ventral tegmental area and adjacent regions. Behav Neurosci. 1997b;111:369–380. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izenwasser S, Heller B, Cox BM. Continuous cocaine administration enhances mu- but not delta-opioid receptor-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity in nucleus accumbens. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;297:187–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW, North RA. Opioids excite dopamine neurons by hyperpolarization of local interneurons. J Neurosci. 1992a;12(2):483–488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW, North RA. Two types of neurone in the rat ventral tegmental area and their synaptic inputs. J Physiology. 1992b;450:455–468. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce EM, Iversen SD. The effect of morphine applied locally to mesencephalic dopamine cell bodies on spontaneous motor activity in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1979;14:207–212. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(79)96149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Churchill L, Klitenick MA. GABA and enkephalin projection from the nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum to the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience. 1993;57(4):1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90048-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Nakamura M. Neural systems for behavioral activation and reward. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9(2):223–227. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Park WK, Jang CG, Oh KW, Kong JY, Oh S, Rheu HM, Cho DH, Kang SY. Blockade by naloxone of cocaine-induced hyperactivity, reverse tolerance and conditioned place preference in mice. Behav Brain Res. 1997;85:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathon DS, Lesscher HM, Gerrits MA, Kamal A, Pintar JE, Schuller AG, Spruijt BM, Burbach JP, Smidt MP, van Ree JM, Ramakers GM. Increased GABAergic input to ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons associated with decreased cocaine reinforcement in mu-opioid receptor knockout mice. Neuroscience. 2005;130(2):359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Marshall JF. Altered prelimbic cortex output during cue-elicited drug seeking. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6889–6897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1685-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldow RL, Fischman AJ. Cocaine induced secretion of ACTH, beta-endorphin, and corticosterone. Peptides. 1987;8:819–822. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(87)90065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander JL, Baker DA, Fuchs RA, Tran-Nguyen LT, Palmer A, Marshall JF. Fos protein expression and cocaine-seeking behavior in rats after exposure to a cocaine self-administration environment. J Neurosci. 2000;20:798–805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00798.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaysen LC, Justice JB., Jr. Effects of cocaine on release and uptake of dopamine in vivo: differentiation by mathematical modeling. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;31:327–335. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90354-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive MF, Koenig HN, Mannini MA, Hodge CW. Stimulation of endorphin neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens by ethanol, cocaine, and amphetamine. J Neurosci. 2001;21(23):RC184. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead MC, Franklin KB. The development of a conditioned place preference to morphine: effects of microinjections into various CNS sites. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:1324–1334. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.6.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press Inc.; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit HO, Justice JB. Dopamine in the nucleus accumbens during cocaine self-administration as studied by in vivo microdialysis. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1989;34(4):899–904. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontieri FE, Tanda G, Di Chiara G. Intravenous cocaine, morphine, and amphetamine preferentially increase extracellular dopamine in the “shell” as compared with the “core” of the rat nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:12304–12308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey NF, Gerrits MA, Van Ree JM. Naltrexone affects cocaine self-administration in naive rats through the ventral tegmental area rather than dopaminergic target regions. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;9:93–99. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(98)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science. 1987;237:1219–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.2820058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Koob GF. Disruption of cocaine self-administration following 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the ventral tegmental area in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;17:901–904. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90469-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth-Deri I, Zangen A, Aleli M, Goelman RG, Pelled G, Nakash R, Gispan-Herman I, Green T, Shaham Y, Yadid G. Effect of experimenter-delivered and self-administered cocaine on extracellular beta-endorphin levels in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurochem. 2003;84:930–938. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JA, Niculescu M, Unterwald EM. Cocaine alters mu but not delta or kappa opioid receptor-stimulated in situ [35S] GTPgammaS binding in rat brain. Synapse. 2003;47(1):26–32. doi: 10.1002/syn.10148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JA, Hummel M, Simpson AD, Sheikh R, Soderman AR, Unterwald EM. A role for mu opioid receptors in cocaine-induced activity, sensitization, and reward in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;195(2):265–272. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0883-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellings LH, Clarke PD. Segregation of amphetamine reward and locomotor stimulation between nucleus accumbens medial shell and core. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6295–6303. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06295.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegfried B, Filibeck U, Gozzo S, Castellano C. Lack of morphine-induced hyperactivity in C57BL/6 mice following striatal kainic acid lesions. Behav Brain Res. 1982;4:389–399. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(82)90063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoubis PD, Maidment NT. Blockade of ventral pallidal opioid receptors induces a conditioned place aversion and attenuates acquisition of cocaine place preference in the rat. Neuroscience. 2003;119:241–249. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang XC, McFarland K, Cagle S, Kalivas P. Cocaine-induced reinstatement requires endogenous stimulation of mu-opioid receptors in the ventral pallidum. J Neurosci. 2005;25(18):4512–4520. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0685-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempel A, Zukin RS. Neuroanatomical patterns of the mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptors of rat brain as determined by quantitative in vitro autoradiography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(12):4308–4312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterwald EM, Rubenfeld JM, Kreek MJ. Repeated cocaine administration upregulates kappa and mu, but not delta, opioid receptors. Neuroreport. 1994;5(13):1613–1616. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199408150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamsley JK, Gehlert DR, Fillloux FM, Dawson TM. Comparison of the distribution of D-1 and D-2 dopamine receptors in the rat brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 1989;2(3):119–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahm DS, Zaborsky L, Alones VE, Heimer L. Evidence for the coexistence of glutamate decarboxylase and met-enkephalin immunoreactivities in axon terminals of rat ventral pallidum. Brain res. 1985;325:33–50. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahm DS, Heimer L. Two transpallidal pathways originating in the rat nucleus accumbens. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302(3):437–446. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]