Abstract

Objective:

As care shifts to home and community, have nursing jobs followed? We examined changes in the absolute and relative size of the nursing workforce by sector/sub-sectors in Ontario, Canada.

Methods:

All nurses registered with the Ontario College of Nurses over the 11 years from 1993 to 2003 were categorized as Active, Eligible or Not Eligible. Active nurses were then categorized by sector (Hospital, Community, Other) and sub-sector. The analysis was repeated by age group and for registered nurses and registered practical nurses.

Results:

The decline in Active and Eligible nurses was particularly pronounced for younger workers. Both the absolute number and proportion of nurses working in the hospital sub-sector has dropped. In the community sector, growth was evident in the use of nurses as case managers (in the CCAC sub-sector), community agencies and community mental health (representing a shift from hospital-based workers). However, the steady growth in the number and proportion of nurses working in home care agencies was reversed in 1999, with this sub-sector shedding 19% of its nurses by 2003.

Conclusion:

Despite considerable rhetoric to the contrary, nurses still tend to work within institutions (hospitals and long-term-care facilities). However, compared to their numbers in 1993, there were fewer nurses providing direct patient care in Ontario in both the hospital and community sectors, and a higher proportion of older nurses.

Abstract

Objectif :

De plus en plus, les soins de santé sont dispensés à domicile et dans la communauté; observe-t-on la même tendance dans les emplois en soins infirmiers? Nous avons examiné la taille absolue et relative de la main-d’oeuvre infirmière par secteur et par sous-secteur en Ontario, au Canada.

Méthodes :

Toutes les infirmières autorisées par l’Ordre des infirmières et infirmiers de l’Ontario de 1993 à 2003 inclusivement ont été répertoriées en trois catégories : actives, admissibles ou non admissibles. Nous avons ensuite répertorié les infirmières actives par secteur (hospitalier, communautaire, autre) et par sous-secteur. L’analyse a été répétée par groupe d’âge et pour les IA et les IAA.

Résultats :

La baisse du nombre d’infirmières actives et admissibles était particulièrement prononcée chez les infirmières plus jeunes. On a également observé une baisse tant dans le nombre absolu que dans la proportion d’infirmières travaillant dans le sous-secteur hospitalier. Le secteur communautaire affiche une hausse dans le recours aux infirmières comme gestionnaires de cas (dans le sous-secteur du CCAC), les organismes communautaires et la santé mentale communautaire (signe d’un délaissement progressif du milieu hospitalier). Cependant, la croissance soutenue du nombre et de la proportion d’infirmières travaillant pour des agences de soins à domicile s’est renversée en 1999 et, en 2003, ce sous-secteur avait perdu 19 % de ses infirmières.

Conclusion :

Malgré tous les arguments contraires, la plupart des infirmières évoluent encore en milieu institutionnel (hôpitaux et établissements de soins de longue durée). Toutefois, comparativement aux chiffres de 1993, moins d’infirmières et une plus grande proportion d’infirmières plus âgées prodiguaient des soins directs aux patients en Ontario dans les secteurs hospitalier et communautaire.

Nurses are globally acknowledged as the linchpin of the healthcare system, delivering a high proportion of the care given in hospitals. However, in recent years the tendency has been to deemphasize hospitals and shift care to home and community (Home Care Sector Study Corporation 2003; MacAdam 2000; Motiwala et al. 2005; Penning et al. 2002). To assess the impact of these hospital downsizing initiatives on the size and distribution of the nursing workforce across various employment settings, we analyzed employment patterns in the province of Ontario, Canada, which employs 36.4% of all Canadian nurses (Canadian Institute for Health Information [CIHI] 2004a, b).

The Policy Backdrop

Researchers and policy analysts have continued to urge a shift of emphasis away from hospital care, reinforced by national reviews of healthcare (Kirby 2002; Romanow 2002) and endorsed by statements by the federal government (Health Canada 2004a,b) and by provincial governments (Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care 2004). In Ontario, the period between 1993 and 2003 witnessed severe constraints on hospital budgets, an active process intended to restructure and downsize the hospital sector, and a shift of patient care from hospitals to the community (Hospital Report Research Collaborative 2001; Heitlinger 2003; Ontario Health Coalition 1999). Indeed, despite persistent concerns by government about the size of hospital budgets, the Ontario Hospital Association (2005) has estimated that Ontario’s per capita 2005 hospital spending, adjusting for inflation, was lower than in 1993. The emphasis on controlling hospital budgets forced the closure of some hospitals and thousands of hospital beds (Heitlinger 2003). In addition, provincial government policy has been closing provincial psychiatric hospitals and attempting to move mental healthcare to not-for-profit public hospitals and to the community (Health Services Restructuring Committee 2000). There have also been significant reductions in length of stay – from 7.0 and 211 days for acute and chronic hospitals, respectively, in 1993 to 6.5 and 100 days in 2003 (Ontario Hospital Association 2005), much of this predicated on the assumption that follow-up care would be offered by home and community services (Baranek et al. 2004).

At the same time as hospital budgets were being constrained, home and community healthcare services were being strengthened by significant governmental investments (Canadian Union of Public Employees 2005; MacAdam 2000; Romanow 2002). These investments were made in anticipation of an increased demand for community and home care services due to population aging, technological and pharmacological advances and a decreasing number of informal caregivers (MacAdam 2000; Motiwala et al. 2005; O’Brien-Pallas et al. 2000), coupled with complaints about a shortage of nurses in the community (Canadian Home Care Human Resources Study Steering Committee 2002; Heitlinger 2003; MacAdam 2000; Ontario Association of Community Care Access Centres [OACCAC] 2000).

To the extent that nurses have historically worked primarily in hospitals, this ongoing restructuring suggests two plausible scenarios. Nurses affected by hospital restructuring may be removed from the healthcare workforce; alternatively, the shrinkage of some sub-sectors may be compensated for by the growth of others. In addition, these trends may differentially affect registered nurses and registered practical nurses.

Differences between RNs and RPNs

In Ontario, nursing is one profession with two categories, registered nurse (RN) and registered practical nurse (RPN). Although both categories share a legislated scope of practice, critical practice differences exist. RNs in Ontario graduate with a baccalaureate degree in nursing, while RPNs graduate with a two-year practical nursing diploma. Differences between the two categories also exist in the depth and breadth of knowledge that is covered, in the competencies that are developed and in the expectations for clinical performance. RNs enjoy a higher level of autonomy in practice and are expected to deal with patients of higher acuity and complexity (College of Nurses of Ontario [CNO] 2004a).

Research Questions

The study aimed to answer the following questions:

Over the period from 1993–2003, how have the numbers and proportion of nurses actively working in Ontario, and of those who are “eligible” but not currently working as a nurse in Ontario, changed? Are the patterns different for different age groups? For RNs and RPNs?

How has the proportion of nurses working in various sectors and sub-sectors employing nurses in Ontario changed? Are these patterns different for RNs and RPNs?

Has the rhetoric about deemphasizing hospital care translated into a decrease in the number of nurses working in institutions?

Methods

In order to answer these questions and to observe the fluctuations in the aggregate number and percentage of nurses working in a particular sector, we carried out an analysis of 11 years (1993 to 2003) of the College of Nurses of Ontario (CNO) registration database. Access to the anonymized CNO database was made available for this study via the Nursing Health Services Research Unit (NHSRU), a collaborative project of the University of Toronto Faculty of Nursing and McMaster University School of Nursing as part of the larger Health Human Resources Project. The CNO reviewed the proposal and gave permission to the Unit to provide the database for analysis.

The database

Registration with the CNO is a prerequisite for RNs and RPNs to practise nursing in Ontario. Upon registration, each nurse is assigned a unique registration number; afterwards, nurses are required to fill out and submit an annual membership renewal to CNO in order to be eligible to work. Nurses who fail to renew their registration within the first six months of the current practice year have their memberships suspended and thus may not practise as a nurse in Ontario; nor do they have the right to use the protected title RN or RPN in the province. Nurses have an incentive to keep their registration active even if they are temporarily out of work to avoid the requirements involved in reinstating their registration (which involves both paperwork and the possible need to pass competency examinations or take refresher courses).

For each year, a subset of the data was created containing a specified set of variables for all nurses registered in that year. The research team checked the data for consistency. This involved examining the CNO registration forms for the period of the analysis (1993-2003) to ensure consistency of the definition of sub-sectors across years; some collapsing of subcategories was required. Data analysis was performed in SAS-PC, using PROC FREQ and PROC MEANS. The key variables used in the analysis were employment status, employment place, registration type (RN/RPN) and age. Frequencies for each year were generated.

Over time, nurses can enter and exit a series of work settings. For each nurse and each year, we first categorized work status into Active, Eligible, Not Eligible and Unknown, as shown in Table 1. For the purpose of this analysis, we classified nurses over age 65 as retired and the small numbers of nurses working at more than one job, where at least one was in Ontario, as part of the pool of active Ontario nurses.

TABLE 1.

Definition of nurses’ work status

| WORK STATUS | INCLUDES NURSES WHO ARE |

|---|---|

| Active | Registered and working in nursing in Ontario |

| Eligible | Registered in Ontario, not employed; Registered in Ontario, but working in nursing outside the province; and Registered in Ontario, but working in non-nursing jobs |

| Not eligible | Retired or over age 65 |

| Missing/Unknown | Work status and employment place unknown |

The Eligible category includes nurses who are actively seeking employment, as well as those more loosely attached to the potential nursing workforce (e.g., those under age 65 but not seeking employment, those working outside the province). Some of these absences may be temporary (e.g., family obligations) and others more permanent. However, all have chosen to maintain their registration. The eligible category thus reflects the “first line” of available nurses who might be readily available should jobs appear. However, it is not known how many of this category, given an opportunity, would make themselves available to work.

For all nurses in the Active category, work settings were categorized into three aggregate sectors, each containing a series of sub-sectors (Table 2). Note that this aggregate categorization differs slightly from that reported annually by CNO in that it includes Long-Term Care (LTC) facilities and agency nurses (who tend to work in hospitals) within the hospital/LTC sector. However, these distinctions are preserved in the analysis of sub-sectors. Appendix A provides the most recent definition of these sub-sectors (CNO 2005).

TABLE 2.

Nursing sectors and sub-sectors of employment

| SECTOR | SUB-SECTORS |

|---|---|

| Hospital/LTC sector | Acute, Chronic, LTC, Rehabilitation, Psychiatric, Agency Nursing, Other Hospitals |

| Community sector | Community Care Access Centres (CCAC), Community Health Centres (CHC), Community Mental Health, Community Home Care, Community Agencies, Public Health |

| Other | Education, Business, Government, Nursing Station, Physician Office, Self-employed, Miscellaneous |

| Not specified | Working as nurses but failed to provide workplace information Working as nurses but did not specify whether in or outside Ontario |

Results

Employment trends

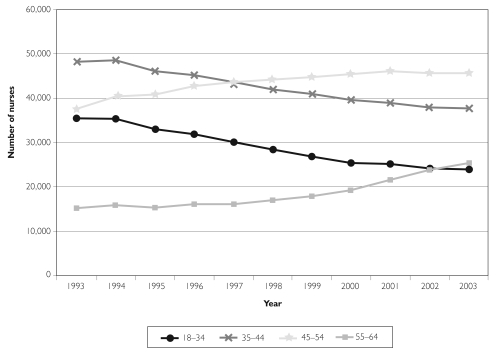

Table 3 displays the number of nurses working as a nurse (Active) and those Eligible to work; the Not Eligible category is omitted, since such nurses by definition would not readily be available to work in the province. We defined “total available” nurses as the sum of Actives and Eligibles. The pool of active nurses for RNs decreased from 1993 to 1999 but began to recover afterwards. In 2003, enough new RNs were hired that the active pool surpassed the 1993 value. The number and percentage of active RPNs decreased through the period of the analysis (–538/–2%). Examining the number of total available nurses, we note that by 1999, a net loss of 5,765 RNs and 1,510 RPNs had occurred; even by 2003, despite the entry of newly trained nurses, there were 1,211 fewer RNs and 1,964 fewer RPNs than at the start of the decade. We next examined the total available nurses by age group (Figure 1). Results show that the available pool of younger nurses in both the 18–34 and 35–44 age groups has been steadily shrinking. On the other hand, the available pool of older nurses, aged 45–54 and 55–64, has grown steadily. This finding confirms reports that suggest an aging nursing workforce (O’Brien-Pallas et al. 2003; CIHI 2004a, b; Canadian Nurses Association 2003). This steady decrease in younger nurses also suggests that the increases in the pool of active RNs reported since 2000 (Table 3) may be less a reflection of new trainees than of older nurses rejoining the active workforce.

TABLE 3.

Number of active, eligible and total available RNs and RPNs (1993–2003)

| YEAR/WORK STATUS | ACTIVE | ELIGIBLE | TOTAL AVAILABLE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNs | RPNs | RNs | RPNs | RNs | RPNs | |

| 1993 | 84,941 | 26,351 | 20,378 | 6,407 | 105,319 | 32,758 |

| 1994 | 83,902 | 26,825 | 23,521 | 7,599 | 107,423 | 34,424 |

| 1995 | 80,763 | 25,352 | 22,771 | 7,611 | 103,534 | 32,963 |

| 1996 | 81,629 | 25,771 | 22,363 | 7,208 | 103,992 | 32,979 |

| 1997 | 80,242 | 25,703 | 21,604 | 6,701 | 101,846 | 32,404 |

| 1998 | 79,038 | 25,599 | 21,396 | 6,185 | 100,434 | 31,784 |

| 1999 | 77,872 | 25,189 | 21,682 | 6,059 | 99,554 | 31,248 |

| 2000 | 82,426 | 26,177 | 17,268 | 4,563 | 99,694 | 30,740 |

| 2001 | 83,503 | 26,591 | 18,521 | 4,598 | 102,024 | 31,189 |

| 2002 | 83,154 | 25,766 | 19,065 | 5,034 | 102,219 | 30,800 |

| 2003 | 85,056 | 25,817 | 19,052 | 4,977 | 104,108 | 30,794 |

FIGURE 1.

Total available nurses per year by age group (1993–2003)

Employment by sector

Table 4 displays the employment of RNs and RPNs in Ontario by aggregate sector between 1993 and 2003. Results show a reduction in both RNs (–5,339/–8.4%) and RPNs (–3223/–14.3%) working in the hospital/LTC sector. In contrast, the community sector has shown an increase in the number of RNs (+2,286/+24.5%) and a large percentage increase in the number of RPNs (+1,213/+76.9%). The number for both nursing categories increased steadily up till 2001 before decreasing afterwards. The “other” sector has also witnessed an increase in the number and percentage of both RNs (+952/+8.1%) and RPNs (+303/+14.8%). Finally, the sharp increase in the number of “not specified” settings starting in 2002 can be directly attributed to a change in the processing of membership renewal forms that occurred at that time. Prior to 2002, nurses’ employment information from the previous year was preprinted and nurses were asked to correct it if needed; otherwise, they were to leave it blank. However, beginning in 2002, the prior information was no longer provided, and nurses were required to fill in their employment information each year. In 2003, 3.1% of RNs and 5.1% of RPNs working in Ontario fell into this category.

TABLE 4.

Employment of nurses by sector and registration type (1993–2003)

| YEAR/WORK STATUS | HOSPITAL/LTC | COMMUNITY | OTHER | NOT SPECIFIED | TOTAL ACTIVE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REGISTRATION TYPE | RNs | RPNs | RNs | RPNs | RNs | RPNs | RNs | RPNs | RNs | RPNs |

| 1993 | 63,469 | 22,577 | 9,336 | 1,578 | 11,723 | 2,053 | 413 | 143 | 84,941 | 26,351 |

| 1994 | 61,741 | 22,473 | 9,157 | 1,808 | 12,422 | 2,282 | 582 | 262 | 83,902 | 26,825 |

| 1995 | 59,689 | 21,181 | 9,653 | 2,103 | 10,613 | 1,755 | 808 | 313 | 80,763 | 25,352 |

| 1996 | 59,285 | 21,221 | 9,538 | 2,054 | 11,520 | 1,827 | 1,286 | 669 | 81,629 | 25,771 |

| 1997 | 57,056 | 21,027 | 10,298 | 2,202 | 12,398 | 2,111 | 490 | 363 | 80,242 | 25,703 |

| 1998 | 54,182 | 19,981 | 10,430 | 2,301 | 13,199 | 2,476 | 1,227 | 841 | 79,038 | 25,599 |

| 1999 | 53,404 | 19,803 | 11,292 | 2,581 | 12,733 | 2,592 | 443 | 213 | 77,872 | 25,189 |

| 2000 | 56,612 | 20,675 | 12,195 | 2,757 | 13,360 | 2,572 | 259 | 173 | 82,426 | 26,177 |

| 2001 | 57,398 | 20,551 | 12,552 | 2,981 | 13,209 | 2,889 | 344 | 170 | 83,503 | 26,591 |

| 2002 | 55,549 | 19,072 | 11,905 | 2,844 | 12,480 | 2,410 | 3,220 | 1,440 | 83,154 | 25,766 |

| 2003 | 58,130 | 19,354 | 11,622 | 2,791 | 12,675 | 2,356 | 2,629 | 1,316 | 85,056 | 25,817 |

| # change 93–03 | –5,339 | –3,223 | +2,286 | +1,213 | +952 | +303 | +2,216 | +1,173 | +115 | –534 |

| % change 93–03 | –8.4 | –14.3 | +24.5 | +76.9 | +8.1 | +14.8 | +536.6 | +820.3 | +0.1 | –2.0 |

A closer analysis reveals that this pattern of growth/contraction of the workforce is not uniform across the various sub-sectors within these sectors. Tables 5 through 7 display employment of RNs and RPNs by sub-sector within each sector.

TABLE 5.

Number of RNs and RPNs working in the hospital/LTC sub-sectors (1993–2003)

| REGISTERED NURSES SUB-SECTOR/YEAR | ACUTE | CHRONIC/REHAB | OTHER | PSYCHIATRIC | LTC | AGENCY | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 48,364 | 3,399 | 1,598 | 2,593 | 6,640 | 875 | 63,469 |

| 1994 | 47,223 | 3,415 | 1,145 | 2,492 | 6,462 | 1,004 | 61,741 |

| 1995 | 45,500 | 3,193 | 1,512 | 2,440 | 6,423 | 621 | 59,689 |

| 1996 | 45,169 | 2,948 | 1,221 | 2,461 | 6,770 | 716 | 59,285 |

| 1997 | 43,156 | 2,764 | 1,094 | 2,362 | 6,940 | 740 | 57,056 |

| 1998 | 40,928 | 2,525 | 1,096 | 2,316 | 6,616 | 701 | 54,182 |

| 1999 | 40,448 | 2,493 | 1,065 | 2,206 | 6,499 | 693 | 53,404 |

| 2000 | 43,245 | 2,576 | 1,139 | 2,227 | 6,812 | 613 | 56,612 |

| 2001 | 45,069 | 1,980 | 1,142 | 2,175 | 6,467 | 565 | 57,398 |

| 2002 | 43,077 | 2,447 | 1,293 | 1,790 | 5,999 | 943 | 55,549 |

| 2003 | 45,349 | 2,349 | 1,292 | 1,830 | 6,328 | 982 | 58,130 |

| # change 93–03 | –3,015 | –1,050 | –306 | –763 | –312 | +107 | –5,339 |

| % change 93–03 | –6.2 | –30.9 | –19.1 | –29.4 | –4.7 | +12.2 | –8.4 |

| REGISTERED PRACTICAL NURSES SUB-SECTOR/YEAR | ACUTE | CHRONIC/REHAB | OTHER | PSYCHIATRIC | LTC | AGENCY | TOTAL |

| 1993 | 11,110 | 3,263 | 241 | 1,858 | 5,733 | 372 | 22,577 |

| 1994 | 10,691 | 3,449 | 204 | 1,814 | 5,788 | 527 | 22,473 |

| 1995 | 10,113 | 3,321 | 178 | 1,702 | 5,644 | 223 | 21,181 |

| 1996 | 9,995 | 3,143 | 153 | 1,731 | 5,956 | 243 | 21,221 |

| 1997 | 9,692 | 3,027 | 138 | 1,671 | 6,244 | 255 | 21,027 |

| 1998 | 8,859 | 2,896 | 159 | 1,621 | 6,176 | 270 | 19,981 |

| 1999 | 8,425 | 2,840 | 151 | 1,603 | 6,473 | 311 | 19,803 |

| 2000 | 8,740 | 2,872 | 155 | 1,634 | 6,944 | 330 | 20,675 |

| 2001 | 8,910 | 2,387 | 174 | 1,640 | 7,117 | 323 | 20,551 |

| 2002 | 7,751 | 2,324 | 195 | 1,343 | 6,954 | 505 | 19,072 |

| 2003 | 7,753 | 2,316 | 161 | 1,317 | 7,356 | 451 | 19,354 |

| # change 93–03 | –3,357 | –947 | –80 | –541 | +1,623 | +79 | –3,223 |

| % change 93–03 | –30.2 | –29.0 | –33.2 | –29.1 | +28.3 | +21.2 | –14.3 |

TABLE 7.

Number of RNs and RPNs working in the “other” sub-sectors (1993–2003)

| REGISTERED NURSES SECTOR/NUMBER | MD OFFICE | BUSINESS | EDUCATION | GOV’T/ASSOC. | NSG. STATION | SELF-EMPLOYED | MISC. | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 3,129 | 1,319 | 2,640 | 1,085 | 129 | 555 | 2,866 | 11,723 |

| 1994 | 3,221 | 1,334 | 2,357 | 1,076 | 142 | 629 | 3,663 | 12,422 |

| 1995 | 3,082 | 1,285 | 2,033 | 972 | 153 | 561 | 2,527 | 10,613 |

| 1996 | 3,071 | 1,287 | 1,949 | 1,122 | 143 | 594 | 3,354 | 11,520 |

| 1997 | 3,133 | 1,338 | 1,787 | 1,048 | 172 | 778 | 4,142 | 12,398 |

| 1998 | 3,068 | 1,321 | 1,706 | 1,098 | 140 | 814 | 5,052 | 13,199 |

| 1999 | 2,956 | 1,305 | 1,621 | 1,175 | 151 | 887 | 4,638 | 12,733 |

| 2000 | 3,060 | 1,385 | 1,760 | 1,306 | 144 | 1,011 | 4,694 | 13,360 |

| 2001 | 2,973 | 1,405 | 1,804 | 1,361 | 200 | 1,052 | 4,414 | 13,209 |

| 2002 | 2,717 | 962 | 2,042 | 1,246 | 179 | 893 | 4,441 | 12,480 |

| 2003 | 2,621 | 912 | 2,113 | 1,210 | 196 | 908 | 4,715 | 12,675 |

| # change 1993–2003 | –508 | –407 | –527 | +125 | +67 | +353 | +1,849 | +952 |

| % change 1993–2003 | –16.2 | –30.9 | –20.0 | +11.5 | +51.9 | +63.6 | +64.5 | +8.1 |

| REGISTERED PRACTICAL NURSES SECTOR/NUMBER | MD OFFICE | BUSINESS | EDUCATION | GOV’T/ASSOC. | NSG. STATION | SELF-EMPLOYED | MISC. | TOTAL |

| 1993 | 810 | 116 | 158 | 141 | 12 | 130 | 686 | 2,053 |

| 1994 | 830 | 125 | 153 | 151 | 25 | 155 | 843 | 2,282 |

| 1995 | 766 | 112 | 97 | 106 | 12 | 136 | 526 | 1,755 |

| 1996 | 742 | 108 | 89 | 121 | 5 | 135 | 627 | 1,827 |

| 1997 | 710 | 98 | 91 | 114 | 7 | 189 | 902 | 2,111 |

| 1998 | 666 | 102 | 85 | 112 | 7 | 169 | 1,335 | 2,476 |

| 1999 | 726 | 91 | 91 | 114 | 9 | 204 | 1,357 | 2,592 |

| 2000 | 771 | 101 | 128 | 133 | 9 | 233 | 1,197 | 2,572 |

| 2001 | 807 | 106 | 148 | 146 | 21 | 266 | 1,395 | 2,889 |

| 2002 | 811 | 95 | 124 | 103 | 14 | 252 | 1,011 | 2,410 |

| 2003 | 791 | 74 | 124 | 89 | 9 | 224 | 1,045 | 2,356 |

| # change 1993–2003 | –19 | –42 | –34 | –52 | –3 | +94 | +359 | +303 |

| % change 1993–2003 | –2.3 | –36.2 | –21.5 | –36.9 | –25.0 | +72.3 | +52.3 | +14.8 |

Employment within hospital/LTC sub-sectors

As Table 5 shows, the decrease in the number of active RNs applies to all hospital/LTC sub-sectors except the use of agency nurses. Similarly, the decrease of RPNs applies to all sub-sectors except long-term-care institutions and the use of agency nurses. The acute hospital sub-sector, although it remained the largest employer, unsurprisingly showed the heaviest loss; this sector shed around one-third of its RPNs (–3,357) and 6.2% of its RNs (–3,015). Closures, mergers, a shift in site of care to the community and cuts to hospital services also drove a decrease of nearly 30% of both the RN and the RPN workforce in psychiatric, chronic and rehabilitation hospitals. The two nursing groups differ with respect to employment in LTC facilities, with an increase in employment for RPNs (+1,623/+28.3%) and a decrease for RNs (–312/–4.7%). Finally, there was an increase in the number and percentage of both RNs (+107/+12.2%) and RPNs (+79/+21.2%) employed by nursing agencies. By the end of the decade, RPNs were less likely to be employed in hospitals and more likely to work in long-term care.

Employment within community sub-sectors

Table 6 shows that contrary to the hospital sector, there has been an increase in all community sub-sectors except for home care for RNs and public health for both nursing categories. There are certain community sectors that employ both RNs and RPNs (e.g., community health centres [CHCs], mental health and home care) and other sectors that largely employ RNs (e.g., community care access centres [CCACs] and public health).

TABLE 6.

Number of RNs and RPNs working in community sub-sectors (1993–2003)

| REGISTERED NURSES SUB-SECTOR/NUMBER | HOME CARE | PUBLIC HEALTH | CHC | MENTAL HEALTH | CCAC | COMM. AGENCY | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 5,336 | 3,375 | 625 | NA | NA | NA | 9,336 |

| 1994 | 5,335 | 3,253 | 569 | NA | NA | NA | 9,157 |

| 1995 | 5,714 | 3,361 | 578 | NA | NA | NA | 9,653 |

| 1996 | 6,282 | 2,750 | 506 | NA | NA | NA | 9,538 |

| 1997 | 6,669 | 2,941 | 568 | 120 | NA | NA | 10,298 |

| 1998 | 6,645 | 3,021 | 597 | 167 | NA | NA | 10,430 |

| 1999 | 5,683 | 2,777 | 594 | 278 | 1,628 | 332 | 11,292 |

| 2000 | 5,438 | 3,013 | 643 | 381 | 2,226 | 494 | 12,195 |

| 2001 | 4,943 | 3,199 | 744 | 578 | 2,474 | 614 | 12,552 |

| 2002 | 4,001 | 3,253 | 797 | 684 | 2,500 | 670 | 11,905 |

| 2003 | 3,701 | 3,285 | 817 | 724 | 2,483 | 612 | 11,622 |

| # change 1993*–2003 | –1,635 | –90 | +192 | +604* | +855* | +280* | +2,286 |

| % change 1993*–2003 | –30.6 | –2.7 | +30.7 | +503.3 | +52.5 | +84.3 | +24.5 |

| REGISTERED PRACTICAL NURSES SUB-SECTOR/NUMBER | HOME CARE | PUBLIC HEALTH | CHC | MENTAL HEALTH | CCAC | COMM. AGENCY | TOTAL |

| 1993 | 1,121 | 315 | 142 | NA | NA | NA | 1,578 |

| 1994 | 1,334 | 339 | 135 | NA | NA | NA | 1,808 |

| 1995 | 1,548 | 416 | 139 | NA | NA | NA | 2,103 |

| 1996 | 1,663 | 281 | 110 | NA | NA | NA | 2,054 |

| 1997 | 1,714 | 323 | 111 | 54 | NA | NA | 2,202 |

| 1998 | 1,778 | 318 | 135 | 70 | NA | NA | 2,301 |

| 1999 | 1,851 | 251 | 169 | 137 | 35 | 138 | 2,581 |

| 2000 | 1,894 | 216 | 200 | 171 | 54 | 222 | 2,757 |

| 2001 | 1,916 | 200 | 243 | 289 | 72 | 261 | 2,981 |

| 2002 | 1,583 | 151 | 260 | 422 | 90 | 338 | 2,844 |

| 2003 | 1,524 | 109 | 272 | 493 | 76 | 317 | 2,791 |

| # change 1993*–2003 | +403 | –206 | +130 | +439* | +41* | +179* | +1,213 |

| Total % change 1993*–2003 | +36.0 | –65.4 | +91.5 | +813.0 | +117.1 | +129.7 | +76.9 |

Change based on 1993, or the first year sub-sector’s information became available.

The most significant increase for both RNs and RPNs was in the newly formed sub-sectors: community mental health, CCACs and community agencies. The increases in these sub-sectors were more pronounced for RPNs over the period of the analysis. The increase in community mental health (+604 RNs and +439 RPNs) is close to the decrease recorded in the psychiatric hospital sub-sector (–763 RNs and –541 RPNs), suggesting a transfer of the mental health workforce from hospitals to community. The number of RNs providing direct patient care through the provincial home care program (e.g., those working in the home care agencies sub-sector) increased steadily between 1993 and 1998 but gradually decreased afterwards. Indeed, that sub-sector lost close to one-third of its RNs between 1999 and 2003 (–1,635/–30.6%). In contrast, the period of the analysis witnessed increased employment of RPNs in home care agencies up until 2001 (+795/+70.9%), followed by a decrease in employment afterwards. The number of nurses working in the public health sub-sector remained steady for RNs and decreased substantially for RPNs (–206/–65.4%).

Employment within “other” sub-sectors

Table 7 compares the numbers of nurses working in the “other” sub-sectors for the years 1993 to 2003. A similar variability across sub-sectors is evident. There are fewer RNs and RPNs employed in physicians’ offices, by business and within education. More RNs and RPNs are claiming to be self-employed – a category that may or may not hide the absence of regular work – or are working in the newer sub-sectors encompassed in the “miscellaneous” category (e.g., cancer centres, blood services). Note that some of these may reflect transfer and recategorization of formerly hospital-based activities now being provided in ambulatory clinics. The employment trends for the two nursing categories differ with respect to governments/associations and nursing stations. There has been a growth in the number of RNs working in these two sectors and a decrease in RPNs. It must be noted, though, that most of the other sub-sectors employing RPNs exhibit high rates of change, but account for minimal employment.

Discussion

The healthcare restructuring process that took place in the 1990s led to a decrease in the pool of available nurses in Ontario. Unsurprisingly, hospitals suffered the heaviest loss of staff, with RPNs bearing the brunt of staff cuts. One reason is that shorter lengths of stay increased the acuity and complexity of patients remaining in hospitals (Canadian Nursing Advisory Committee [CNAC] 2002). Managers may have concluded that they needed the skill of RNs to care for these patients (CNO 2004a). The need for specialized care and legal requirements could also explain why certain sub-sectors largely employ RNs, for example, public health, CCACs, government and nursing stations.

However, although the number of nurses currently employed in hospitals has been decreasing, and despite the rhetoric about a shift of nurses from hospitals to home and community, in 2003, most Ontario nurses were still working within institutions. This pattern persists; in 2004, the College of Nurses of Ontario reported that hospitals and long-term-care facilities employed 72.7% of RNs and 78.8% of RPNs practising in Ontario (CNO 2004b).

Any workplace has both advantages and disadvantages. In comparison to the home care sector, hospital-based employment may offer relative job stability, higher salaries and benefits, more defined job scope and better prospects for career development (Caplan 2005; Heitlinger 2003; Home Care Sector Corporation 2003); however, it also offers shift work, more stress associated with higher workload, a more hierarchical workplace and decreased autonomy (Baumann et al. 2001; CNAC 2002; Decter and Villeneuve 2001). The continued prominence of hospital-based employment thus requires careful analysis of whether this prominence reflects the net attractiveness of this sub-sector, the relative unattractiveness of alternative jobs, government funding policies or some combination of factors. For example, it would be useful to compare these findings to patterns in jurisdictions where there are not differences in wages and benefits across sub-sectors.

The results suggest that, in aggregate, the nurses displaced by hospital restructuring (–5,339 RNs and –3,223 RPNs) were not absorbed by the community sector (+2,286 RNs and +1,213 RPNs). In a future analysis, we will be examining the career trajectory of individual nurses once employed within hospitals in an attempt to understand the balance between moving to other sub-sectors and leaving the profession.

Similarly, the decrease in the number of RNs working in home care agencies providing direct services (–1,635) represents an abrupt drop in the previous trend line (1993 to 1998) and coincides with the establishment of the competitive bidding process for home care services by CCACs in 1997. These results suggest that the trend toward “managed competition” may have reduced services provided through home care (e.g., through service maxima) and that many of the agencies providing home care services may have chosen to compete for contracts by managing wages and benefits, reducing costs and providing care by lower-cost healthcare workers – for example, by replacing RNs with RPNs or RPNs with unregulated care providers (Shapiro 1997; Aronson et al. 2004; Caplan 2005).

To the extent that home care RNs were also doing case management in the home care programs that preceded CCACs, the reduction in 1999 could be partially attributed to the reclassification of these nurses. However, there is also evidence that fewer nurses were providing care to post-acute home care patients with higher acuity levels and more complex care needs (Parent and Anderson 2001). The drop in nursing employment in the home care sub-sector is also consistent with the reported decrease in the volume of nursing services provided by these agencies – from 7,892,685 visits in 2001/2002 to 6,468,563 in 2002/2003 (OACCAC 2004). Although more RPNs were employed in home care agencies during the period of the analysis, this increase (+403) did not make up for the decrease in the number of RNs (–1,635). In addition, it is noteworthy that RPN employment in home care agencies fell sharply after 2001 (–392 RPNs). While some home-based nursing services may be provided in other ways, such as purchase of private services by patients and families or informal caregiver involvement in providing care, concern has been raised about the increase of such arrangements (Home Care Sector Study Corporation 2003; McAdam 2000; Motiwala et al. 2005). The implications of these trends for home care patients and the system warrant further investigation.

Within the home care sector, a major growth area has been the “administration of care” versus the “provision of care.” RNs have been largely employed by CCACs as case managers, clinical nurse specialists, nurse practitioners and clinical educators. Although these skilled nurses may perform initial assessment, their ongoing role is focused on consultation, and they are often expected to hand off care to the nursing agencies that have won contracts from CCACs. From an educational/training perspective, this implies some need to examine the scope of practice of the community-based nurses and the role that they are playing. Particularly given this shrinking supply, the impact of such trends as role substitution and increased use of unregulated caregivers warrants close monitoring in order to create public policy frameworks that ensure adequate provision of high-quality care (Baumann et al. 2001; CNAC 2002).

Conclusion

Compared to their number in 1993, by 2003 there were fewer RNs and RPNs providing direct patient care in Ontario in both the hospital and community sectors. There were also fewer nurses, especially RPNs, available for work, should public policy decide that more are needed. Given the length of time needed to train a nurse, and the aging of the nursing resource pool, the time available for policy makers to act would appear short if cries of “crisis” are not to become reality.

Acknowledgments

This study has been funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant, “Where Do Nurses Work? Work Setting and Work Choice.” Analysis was performed at the Nursing Health Services Research Unit (NHSRU), Faculty of Nursing, University of Toronto. Additional support was provided by the Medicare to Home and Community (M-THAC) Research Unit, University of Toronto.

Special thanks to the staff of the NHSRU for their help and advice, especially Laureen Hayes and Elisabeth Peereboom, and to Carey Levinton for programming assistance.

Appendix A

Employment Sub-sector Definitions

The sub-sector definitions come from the Instruction Guide for the College of Nurses of Ontario Annual Membership Renewal (CNO 2005). The section “CNO Practice and Employment Definitions” provides definitions “to assist members to make appropriate choices when answering the Annual Membership Renewal questions related to practice and employment” (CNO 2005). Note that because categorization for certain sub-sectors varied over time, we have preserved or merged sub-sectors as required. For example, we have distinguished between “agency nurses” providing services primarily in hospitals and nurses working in “community agencies” providing services in the community. On the other hand, we merged long-term-care subcategories into one category (LTC). Although the definitions have not changed, the way they are aggregated has. For example, the 2005 definition combines the Home Care/Visiting Care Agencies and the Employment Agency/Private Duty categories, adds some new sub-sectors (e.g., hospice) and deletes others (e.g., nursing stations). To minimize confusion we renamed the other “Other” subcategory “Miscellaneous.”

Acute Care Hospital

A category of healthcare facility that is staffed and equipped to deliver care to patients in the acute phase of illness. Acute care hospitals are characterized by having medical, surgical, nursing and allied health professionals available at all times to provide rapid, intensive interventions. These hospitals commonly provide diagnostic services utilizing high technology. An acute care hospital may also provide other non-acute services such as rehabilitation or chronic care.

Addiction and Mental Health Centre/Psychiatric Hospital

A healthcare facility that specializes in treating persons with mental health or addiction problems, or both. Psychiatric hospitals that are part of a larger organization and short-term treatment programs are included in this group.

Complex Continuing Care Hospital (Chronic Hospital)

A hospital that provides care to patients who are unstable and require 24-hour nursing care for chronic or fluctuating serious illness.

Rehabilitation Hospital

A hospital that provides primarily the continuing assessment and treatment of patients whose condition is expected to improve significantly through the provision of physical medicine and other rehabilitative services. Complex continuing care/rehabilitation hospitals that are part of a larger organization are included in this group.

Other Hospital

Any other hospital excluding teaching hospitals, community hospitals, addiction and mental health centres/psychiatric hospitals and complex continuing care/rehabilitation hospitals.

Community Care Access Centre

An organization providing simplified service access to visiting professional and personal support health services at home and in schools, long-term-care placement, service planning and case management, and information and referrals to other long-term-care services, including volunteer-based community services.

Community Health Centre

A not-for-profit, community-governed organization that provides primary healthcare, health promotion and community development services, using multidisciplinary teams of health providers.

Community Mental Health Program

A community program that is not hospital bed–based and that serves people with mental health or addiction problems, or both.

Hospice

An organization whose mission is to help people with life-threatening illnesses live at home or in a home-like setting.

Nursing/Staffing Agency

An agency that provides a range of nursing services to support client care in the community and in healthcare facilities. Services are delivered in homes, hospitals and other settings such as schools and retirement homes.

Physician’s Office/Family Practice Unit

A group or solo practice that provides episodic or continuing, comprehensive primary care.

Public Health Unit/Department

An official health agency established by a group of urban or rural municipalities to develop and provide comprehensive community healthcare programs.

Other Community

Other community sector employers not listed above (e.g., independent health facilities, telehealth, Canadian Blood Services, Workplace Safety and Insurance Board).

Long-Term-Care Facility

A facility for people who are not able to live independently or in their own homes and who require 24-hour nursing service to meet their personal care needs (e.g., long-term-care centre, nursing home, home for the aged).

Retirement Home

A residential complex that is occupied by persons who are primarily 65 years of age or older, for the purpose of receiving care services, whether or not receipt of such services is the primary purpose of occupancy (e.g., care home, rest home, lodge, manor, assisted living).

Other Long-Term-Care Facility

Long-term-care facilities not listed in the definitions (e.g., group home, respite care centre, home for special care).

Colleges/Universities

Postsecondary educational organizations offering nursing programs.

Government/Association/Regulatory/Union

This category includes the provincial and federal governments, the various associations involved in supporting professions and organizations, and the bodies charged with regulating health professions recognized under the Regulated Health Professions Act.

Industry (Business)

A commercial or industrial enterprise involved in the production, manufacturing, processing or sales of goods or services.

Schools

Elementary and secondary schools, public or private.

Self-Employed

An individual earning income directly from one’s own business or profession rather than from a specified salary or wages from an employer (e.g., private practice).

Other (Miscellaneous)

Employers not listed in other definitions.

Contributor Information

Mohamad Alameddine, Doctoral Candidate in Health Policy, Department of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation (HPME), University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

Audrey Laporte, HPME, Toronto, ON.

Andrea Baumann, FHSc International Health, Michael G. DeGroote Centre for Learning and Discovery, McMaster University, Hamilon, ON.

Linda O’Brien-Pallas, Nursing Health Services Research Unit (NHSRU), Faculty of Nursing, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

Ruth Croxford, Sunnybrook and Women’s College Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON.

Barbara Mildon, NHSRU, Toronto, ON.

Sping Wang, NHSRU, Toronto, ON.

Brad Milburn, NHSRU, Toronto, ON.

Raisa Deber, HPME, Toronto, ON.

References

- Aronson J., Denton M., Zeytinoglu I. Market-Modeled Home Care in Ontario: Deteriorating Working Conditions and Dwindling Community Capacity. Canadian Public Policy. 2004;30(1):111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Baranek P., Deber R., Williams P. Almost Home: Reforming Home and Community Care in Ontario. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann A., O’Brien-Pallas L., Armstrong-Stassen M., Blythe J., Bourbonnais R., Cameron S., et al. Commitment and Care: The Benefits of a Healthy Workplace for Nurses, Their Patients and the System. Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Home Care Human Resources Study Steering Committee. Phase I Report. Setting the Stage: What Shapes the Home Care Labour Market? Ottawa: Canadian Council of Health Services Accreditation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Workforce Trends for Registered Nurses in Canada, 2003. Ottawa: Author; 2004a. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Workforce Trends for Licensed Practical Nurses in Canada, 2003. Ottawa: Author; 2004b. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Nurses Association. CNA Renews Call for Urgent Action to Address Impact of Aging Nursing Workforce. 2003 Retrieved November 24, 2005. http://www.cna-nurses.ca/CNA/news/releases/public_release_e.aspx?id=77 .

- Canadian Nursing Advisory Committee (CNAC) Our Health, Our Future: Creating Quality Workplaces for Canadian Nurses. Final report. Ottawa: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Union of Public Employees. Fact Sheet – Health Care Funding in Ontario. 2004 Retrieved November 24, 2005. http://cupe.ca/www/HealthCareResearch/10574 .

- Caplan E. Realizing the Potential of Home Care: Competing for Excellence by Rewarding Results. A Review of the Competitive Bidding Process Used by Ontario’s Community Care Access Centres (CCACs) to Select Providers of Goods and Services. Toronto: CCAC Procurement Review; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- College of Nurses of Ontario (CNO) Practice Guidelines: Utilization of RNs and RPNs. Toronto: Author; 2004a. Retrieved November 24, 2005. http://www.cno.org/docs/prac/41062_UtilizeRnRpn.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- College of Nurses of Ontario (CNO) Membership Statistics Report. Toronto: Author; 2004b. [Google Scholar]

- College of Nurses of Ontario (CNO) 2005 Annual Membership Renewal – Instruction Guide. 2005 Retrieved November 24, 2005. http://www.cno.org/docs/reg/definitions.htm .

- Decter M., Villeneuve M. Repairing and Renewing Nursing Workplaces. Hospital Quarterly. 2001;5(1):46–49. doi: 10.12927/hcq..16696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. First Ministers’ Meeting on the Future of Health Care: A 10-Year Plan to Strengthen Healthcare. 2004a Retrieved August 24, 2005. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/delivery-prestation/fptcollab/2004-fmm-rpm/index_e.html .

- Health Canada. What Is Home and Community Care? 2004b Retrieved November 24, 2005. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/home-domicile/commun/index_e.html .

- Health Services Restructuring Commission. HRSC Internet Web Page Proposed Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) 2000 Retrieved November 24, 2005. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/hsrc/e_gi_faq.htm .

- Heitlinger A. The Paradoxical Impact of Health Care Restructuring in Canada on Nursing As a Profession. International Journal of Health Services. 2003;33(1):37–54. doi: 10.2190/RMAY-NJA9-KFW7-1UEW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Home Care Sector Study Corporation. Canadian Home Care Human Resources Study: Synthesis Report. Ottawa: Author; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hospital Report Research Collaborative. Hospital Report 2001: Acute Care. Ottawa: Canadian Institute of Health Information; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby M. The Health of Canadians – The Federal Role, Volume 6. Ottawa: Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- MacAdam M. Home Care: It’s Time for a Canadian Model. Healthcare Papers. 2000;1(4):9–36. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2000.17348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motiwala S.S., Flood C.M., Coyte P.E., Laporte A. First Ministers and the Future of Home Care. Longwoods Review. 2005;2(4):2–9. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien-Pallas L., Baumann A., Birch S., Tomblin Murphy G. Health Human Resource Planning in Home Care: How to Approach It – That Is the Question. Healthcare Papers. 2000;1(4):53–59. doi: 10.12927/hcpap..17351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien-Pallas L., Alksnis C., Wang S. Bringing the Future into Focus: Projecting the RN Retirement in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Association of Community Care Access Centres (OACCAC) Human Resources: A Looming Crisis in the Community Care System in Ontario. Human Resources Task Group. Scarborough: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Association of Community Care Access Centres (OACCAC) Building an Integrated, Efficient, Accountable and Sustainable Health Care System in Ontario. Scarborough: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Health Coalition. Hospitals Fact Sheets #1 and #2. 1999 Retrieved April 24, 2005. http://www.web.net/~ohc/docs/fact_hospitalpolicy.htm. and http://www.web.net/~ohc/docs/fact_hospitals.htm .

- Ontario Hospital Association. Key Facts and Figures. Addendum to OHA’s Ontario 2005 Budget Submission to the Ontario Standing Committee on Finance and Economic Affairs, Toronto Hearings. Toronto: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. McGuinty Government Makes a Record Investment in Home Care Services. News release. 2004 Retrieved November 24, 2005. http://ogov.newswire.ca/ontario/GPOE/2004/07/05/c0412.html?lmatch=&lang=_e.html .

- Parent K., Anderson M. Home Care by Default, Not by Design: CARP’s Report Card on Home Care in Canada 2001. Toronto: Canadian Association of Retired Persons; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Penning M.J., Roos L.L., Chappell N.L., Roos N.P., Lin G. Healthcare Restructuring and Community-Based Care: A Longitudinal Study. 2002 Retrieved November 24, 2005. http://www.chsrf.ca/final_research/ogc/pdf/penning_final.pdf .

- Romanow R. Building on Values: The Future of Health Care in Canada: Final Report. Saskatoon: Commission on the Future of Health Care; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro E. The Cost of Privatization: A Case Study of Home Care in Manitoba. Winnipeg: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives – Manitoba; 1997. [Google Scholar]