Abstract

Postprandial lipemia test (PPLT) results are predictive of cardiovascular disease risk. However, their reproducibility must be established before they can be clinically useful. Therefore, we investigated PPLT reproducibility by testing nine men and women (BMI, 20–41 kg/m2; age=21–40y) on four separate occasions (n=36 PPLTs total) separated by 1 week. Furthermore, because PPLTs are time consuming, we assessed the validity of an abbreviated PPLT. During the PPLT, venous blood was obtained before and every hour for 8h after a high fat meal, which consisted of ice cream and heavy cream (~800 kcal, 71% fat calories). Total and triglyceride-rich lipoprotein (TRL) triglyceride concentrations were measured in plasma. Total area under the curve (AUC) for total triglycerides was highly reproducible [within-subject coefficient of variation (WCV): 8%; intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC): 0.82]; however, reproducibility was low for total triglyceride incremental AUC and both total and incremental TRL triglyceride AUCs (WCVs: 20–31%; ICCs: 0.28–0.54). Four-hour lipemic responses were highly predictive of 8-hr responses (R2: 0.89–0.96, p≤0.0001). In conclusion, PPLTs are highly reproducible when lipemic responses are determined as the total AUC for total triglycerides. However, large variability in incremental AUC and TRL triglyceride responses may preclude their clinical utility. Furthermore, abbreviated 4-hr PPLTs are a valid surrogate for longer tests and may make PPLTs more feasible in a clinical setting.

Keywords: high-fat meal, fat tolerance test, triglyceride-rich lipoprotein, lipid metabolism

INTRODUCTION

Exaggerated postprandial lipemia after a high-fat meal is associated with increased intima media thickness in the carotid arteries (2), impaired endothelial function (1), insulin resistance (3; 4) and is greater in individuals with cardiovascular disease (CVD) than it is in individuals without CVD (5; 6). Postprandial lipemia is reduced by interventions that decrease insulin resistance and CVD risk including exercise (7), diets low in saturated fat (8), statin therapy (9), and metformin therapy (10). Although the mechanistic relationship between postprandial lipemia and CVD is not clear, chylomicrons and their remnants, which are mainly present in circulation postprandially, can penetrate the endothelium and be retained in the sub-endothelial space (11) where they may trigger the inflammatory reactions involved in atherogenesis. Taken together, these findings suggest that exaggerated postprandial lipemia may promote the development of cardiovascular disease and insulin resistance.

As additional evidence accumulates to suggest that excessive postprandial lipemia may be a cardiometabolic risk factor, postprandial lipemia tests may become clinically useful for assessing disease risk and monitoring responses to risk reduction interventions. However, to be of clinical utility, these tests must be reproducible. Therefore, the primary purpose of the present study was to assess the reproducibility of postprandial lipemia tests in lean and obese individuals. Additionally, because postprandial lipemia tests typically require 8 hours or more to perform, they may not be practical in a clinical setting. Therefore, a secondary purpose of our study was to asses the validity of an abbreviated 4-hour postprandial lipemia test.

METHODS

Subjects

Five lean and four obese subjects participated in the study. A medical history, physical examination, resting electrocardiogram, and standard blood chemistries and lipids were used to identify and exclude volunteers with clinical evidence of cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic or other chronic diseases. A 75-gram glucose tolerance test (12) was used to identify and exclude any of the obese subjects who may have had occult diabetes. Subjects were required to be sedentary (≤1 exercise session/wk and ≤ 30 min/session according to self report) and could not be taking medications known to affect lipid metabolism. Smoking and pregnancy were also exclusionary. The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Committee and the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) Scientific Advisory Committee of Washington University School of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject prior to participation in the study.

Experimental protocol

Each subject completed a postprandial lipemia test (PPLT) on four occasions (n=36 PPLTs total) with approximately 1 week between consecutive tests.

Pre-study dietary intake and physical activity

The subjects were instructed by a registered dietitian to ingest a weight maintaining diet that included ≥250 g/d of carbohydrate and approximately 12% of total energy intake as protein, 55% as carbohydrate and 33% as fat for 3 days prior to each PPLT. Subjects were advised to refrain from exercise and not consume caffeine or alcohol for 24 h prior to each study.

Postprandial lipemia test

Subjects were admitted to the GCRC in the evening before the test. At 1900 h, a standardized meal was consumed which provided approximately 55% of total energy as carbohydrates, 30% as fat, and 15% as protein. The energy content of the meal for lean subjects was 12 kcal/kg screening body weight. To account for different energy requirements per unit body mass in obese subjects, the energy content of the meal was 12 kcal/kg adjusted body weight where adjusted body weight = ideal body weight + 0.25 × (screening body weight - ideal body weight) and ideal body weight was determined from the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tables for individuals with a medium frame (13). After the evening meal, the subjects fasted, except for water, until the PPLT the following day.

At 0530 h on the morning of the PPLT, an intravenous catheter was inserted into a dorsal hand vein for blood sampling. To obtain arterialized blood, the hand was placed in a heating box set at 55°C for 20 min before each blood sample was acquired (14). The catheter was kept patent by infusing 0.9% NaCl at 25 ml/h. At 0630 h, subjects received the high fat meal and consumed it within 20 minutes. The HF meal was prepared by mixing heavy whipping cream (Pevely Dairy Co., St. Louis, MO) and vanilla ice cream (Häagen-Dazs, Ice Cream Partners, San Ramon, CA) in a mass ratio of 1 part heavy cream to 4 parts ice cream. Total energy content was 2.84 kcal per gram of meal. Fat, carbohydrate, and protein provided 71%, 23%, and 6% of the energy in the meal, respectively. The meal dose was 162 g of meal per m2 body surface area (equivalent to 35 g fat/m2), where body surface area was calculated according to DuBois & DuBois (body surface area = 0.20247 × height (m)0.725×weight (kg)0.425). For the duration of the test, the subjects remained recumbent in bed or seated in a chair until the completion of the study at 1430 h. Blood samples for the determination of plasma triglyceride concentrations were obtained immediately before ingestion of the fat meal and every hour for 8 h after the initiation of meal ingestion. Data from the first 4 hr of the tests were interpreted as the abbreviated postprandial lipemia test results. Four hours was chosen as the abbreviated PPLT duration because peak lipemia typically occurs 4 hr after oral fat loads that are of similar magnitude to the one used in the present study and because 4-hr tests have been used previously (4; 15).

Blood Sampling

Blood samples were collected in pre-chilled tubes containing EDTA and kept on ice. Plasma was isolated within 30 min by using standard procedures. A portion of each sample (~2 mL) was kept in the refrigerator for the isolation of TRL; the remainder of the plasma was stored at −70°C for later quantification of total triglycerides.

Isolation of TRL

Immediately after completion of each PPLT, 2 mL plasma were transferred into Optiseal tubes (Beckman, Palo Alto, CA), overlayed with a EDTA/NaCl solution (D = 1.006 kg/mL) and centrifuged for 16h at 100,000 g and 10°C in a 50.4 Ti rotor (Beckman Instruments, Palo Alto, CA) (16). The TRL fraction was recovered by tube slicing (Beckman Instruments, Palo Alto, CA), and the exact amounts recovered (~1.5 mL) were recorded for later calculation of concentrations. TRL fractions were stored at 4°C and triglyceride concentrations were measured within 48 hr of separation from plasma.

Triglyceride Analysis

Total and TRL triglyceride concentrations were determined by performing an enzymatic colorimetric assay (Sigma-Aldrich Co, St. Louis, MO) with a Du Series 500 spectrophotometer (Beckman, Fullerton, CA). The intra-assay variability for the determination of TG concentration in our laboratory is < 6.5%; the variability for the determination of TRL TG concentration in plasma is <10%.

Calculations

The trapezoidal rule (17) was used to calculate total area under the curve (AUC) and AUC above baseline (incremental AUC). For the incremental AUCs, the difference between fasting and postprandial triglyceride values were used in the calculations. Furthermore for the incremental AUCs, postprandial values that were less than fasting values or values that occurred after a value that was less than fasting were excluded. AUCs for the 4-hr tests were calculated using the same approaches as was used for the full-length test except that data after the 4-hr time point were excluded.

Statistical Analyses

Between group comparisons (lean vs. obese) were performed by using independent t-tests. For comparisons of the lipemic responses in the lean and obese groups, the mean of all four tests was used for each subject. Reproducibility of postprandial lipemia was assessed by calculating within-subject coefficient of variation (WCV) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). WCV was calculated by using the logarithmic method (18) and has an advantage over ICC in that it does not depend on the between subject variance and is therefore considered population independent (19). WCV values can be 0% or greater, with lower values representing higher reproducibility. Measures with WCV values of 10–20% or less have been described as having sufficient reproducibility for use in monitoring treatment effects (19); we chose the more strict end of this range (i.e. ≤10%) as the criterion for high reproducibility in the present study. ICC was calculated by using a one-way random alpha model for measurement consistency. ICC has an advantage over WCV in that it does not depend on the mean values (19). ICC values range from 0.00 to 1.00 with higher values reflecting better reproducibility. Based on guidelines used by others, ICC values of ≥0.75 were interpreted as high reproducibility (20; 21). To assess the validity of 4-hr tests for predicting results from the full length tests, linear regression analyses were performed which included data from each subject’s first test only. Significance was accepted at p≤0.05. All data are reported as means ±SEM unless otherwise noted. Analyses were performed with SAS for Windows XP Pro (version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC), SPSS for Windows (version 13.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL), and Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

RESULTS

Subjects

For the group as a whole, age ranged from 21–40 y and BMI from 20–41 kg/m2. Mean age, body weight, and BMI, were greater in the obese group than in the lean group (Table 1). Fasting plasma glucose and lipid concentrations were within normal ranges for all subjects. Plasma insulin and LDL-cholesterol concentrations were higher and HDL-cholesterol was lower in obese than lean subjects.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics.

| Lean N=5 | Obese N=4 | All Subjects N=9 | Lean vs. Obese P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males/females | 1/4 | 1/3 | 2/7 | 1.00 |

| Age, y | 23 ± 1 | 36 ± 4 | 29 ± 5 | 0.01 |

| Body weight, kg | 58 ± 4 | 114 ± 8 | 83 ± 4 | 0.0003 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 21 ± 1 | 40 ± 1 | 29 ± 3 | <0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 84 ± 1 | 99 ± 3 | 91 ± 2 | 0.06 |

| 2-hr glucose, mg/dL* | - | 133 ± 4 | - | - |

| Insulin (µU/ml) | 2 ± 0 | 15 ± 3 | 8 ± 1 | 0.02 |

| Total triglycerides (mg/dL) | 64 ± 15 | 114 ± 23 | 87 ± 15 | 0.10 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 162 ± 11 | 182 ± 12 | 171 ± 8 | 0.26 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 85 ± 5 | 119 ± 9 | 100 ± 5 | 0.01 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 64 ± 5 | 42 ± 6 | 54 ± 4 | 0.03 |

Values are means ± SEM except for males/females data, which are counts. All measures were made after an overnight fast except for 2-hr glucose which was assessed 2-hr after a 75g oral glucose load.

2-hr glucose was only assessed in obese subjects (to screen for occult diabetes).

Average lipemic responses

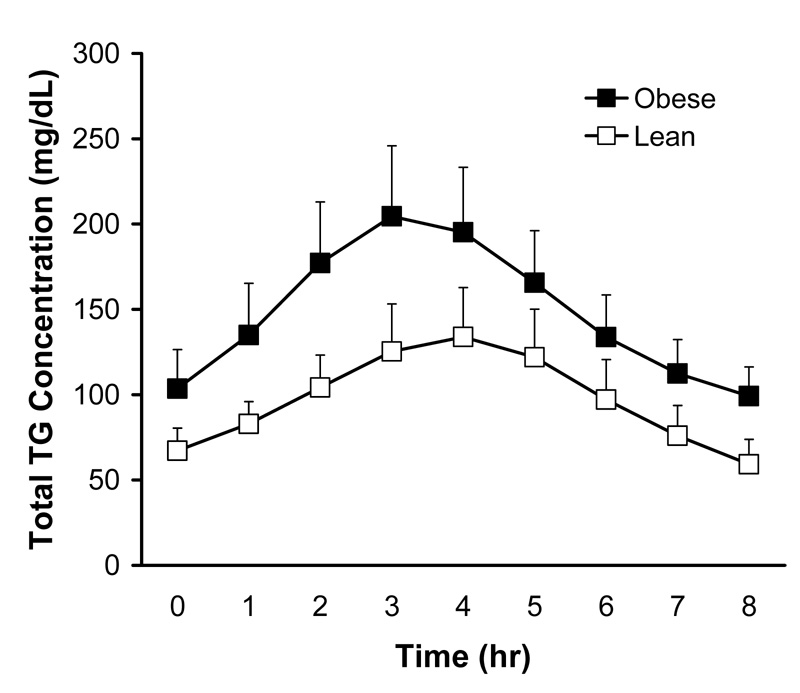

For both lean and obese groups, total plasma triglyceride concentrations doubled from fasting to 3 or 4 hr after the meal and returned to baseline by 8 hr postprandially (Figure 1). Although there was a tendency for obese subjects to have higher fasting and postprandial total triglyceride concentrations, neither the fasting values nor the AUCs were significantly different between groups (Table 2). Furthermore, neither the fasting values nor the AUCs for TRL triglycerides were different between lean and obese participants.

Figure 1.

Time courses for total plasma triglyceride concentrations during the postprandial lipemia test in lean and obese subjects. Values are means + SEM and were calculated by using the mean of four tests for each subject.

Table 2.

Postprandial lipemia test results.

| Lean | Obese | All subjects | Lean vs. Obese P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Triglycerides | ||||

| Fasting, mg/dL | 65 ± 12 | 104 ± 23 | 82 ± 13 | 0.19 |

| Total AUC × 103, mg/dL · min | 46 ± 9 | 73 ± 14 | 58 ± 9 | 0.16 |

| Incremental × 103, mg/dL · min | 16 ± 5 | 24 ± 4 | 19 ± 3 | 0.17 |

| 4h total AUC × 103, mg/dL · min | 24 ± 4 | 40 ± 8 | 31 ± 5 | 0.13 |

| 4h incremental AUC × 103, mg/dL · min | 8 ± 2 | 15 ± 3 | 11 ± 2 | 0.08 |

| Triglyceride Rich Lipoprotein Triglycerides | ||||

| Fasting, mg/dL | 32 ± 8 | 50 ± 19 | 40 ± 10 | 0.59 |

| Total AUC × 103, mg/dL · min | 24 ± 7 | 39 ± 11 | 31 ± 7 | 0.32 |

| Incremental AUC × 103, mg/dL · min | 11 ± 4 | 16 ± 3 | 13 ± 3 | 0.22 |

| 4h total AUC × 103, mg/dL · min | 14 ± 4 | 23 ± 7 | 18 ± 4 | 0.32 |

| 4h incremental AUC × 103, mg/dL · min | 6 ± 2 | 10 ± 2 | 8 ± 2 | 0.16 |

Data are means ± SEM. The means of all 4 tests for each subject were used for statistical analyses. AUC, area under the curve.

Reproducibility Based on Within Subject Coefficient of Variation

The WCV for fasting total triglycerides was low (Table 3), as would be expected for this commonly used clinical measure, with values for lean, obese, and all subjects combined meeting the ≤10% criterion for high reproducibility (19). Total AUC for total triglyceride also had low WCV values, which were comparable to those for fasting TG. In contrast, WCVs for total triglyceride incremental AUC was 2- to 3-fold greater, indicating relatively poor reproducibility. For total TG from the abbreviated 4-hr tests, the total AUC was highly reproducible and comparable to fasting TG while the incremental AUC had 2-fold greater WCV values, indicating substantially lower reproducibility.

Table 3.

Within-subject coefficient of variation for the lipemic response to a high fat meal conducted on four different days.

| Lean | Obese | All Subjects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Triglycerides | |||

| Fasting | 6.3 (4.3, 8.4) | 6.2 (4.0, 8.4) | 6.3 (4.8, 7.8) |

| Total AUC | 9.4 (6.4, 12.6) | 6.0 (3.9, 8.2) | 8.1 (6.1, 10.0) |

| Incremental AUC | 23.5 (15.6, 31.9) | 16.9 (10.6, 23.4) | 20.7 (15.6, 26.1) |

| 4h total AUC | 7.7 (5.2, 10.2) | 5.0 (3.2, 6.8) | 6.6 (5.0, 8.2) |

| 4h incremental AUC | 18.9 (12.6, 25.5) | 11.6 (7.4, 16.0) | 16.0 (12.0, 20.0) |

| Triglyceride Rich Lipoprotein Triglycerides | |||

| Fasting | 11.6 (7.8, 15.5) | 32.4 (19.9, 46.1) | 22.6 (17.0, 28.6) |

| Total AUC | 14.0 (9.4, 18.8) | 25.4 (15.8, 35.8) | 19.7 (14.8, 24.8) |

| Incremental AUC | 29.0 (19.1, 39.7) | 32.5 (20.0, 46.3) | 30.6 (22.7, 39.0) |

| 4h total AUC | 11.0 (7.5, 14.8) | 23.3 (14.5, 32.7) | 17.3 (13.1, 21.8) |

| 4h incremental AUC | 24.9 (16.5, 33.9) | 28.1 (17.4, 39.7) | 26.4 (19.7, 33.4) |

Data are within-subject coefficients of variation (WCVs) reported as percentages with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. Lower WCV values indicate better reproducibility with values ≤10% being reflective of high reproducibility (19).

None of the TRL triglyceride outcomes met the ≤10% criterion for high reproducibility (19). The reproducibility for fasting TRL triglycerides was poor in comparison to fasting total triglycerides as reflected by 2- to 4-fold greater WCV values (Table 3). Similarly, WCVs for AUCs calculated from TRL triglycerides were greater than those for the corresponding total triglyceride AUCs; this was true for the 4-hr tests as well. Total AUCs for TRL triglycerides had lower WCVs than the corresponding incremental AUCs, indicating greater reproducibility for total AUCs.

Reproducibility Based on Intraclass Correlation Coefficients

As expected for a common clinical measure, ICCs for fasting total triglycerides were well above the 0.75 cut point for high reproducibility (20; 21). Likewise, total AUCs for total triglycerides from the full length and abbreviated tests had high ICC values with the exception of the value for obese subjects from the full length test. ICCs for the incremental AUCs for total triglycerides were lower than those for the total AUC. The 4-hr incremental total triglyceride AUCs had better reproducibility than the full length test results.

The reproducibility of fasting TRL triglycerides was modest, with the ICC values for obese subjects and all subjects combined not meeting the 0.75 cut point for high reproducibility (20; 21). Furthermore, the reproducibility for fasting TRL triglycerides was considerably lower than that for fasting total triglycerides. With one exception (4-hr total AUC), none of the ICCs for TRL-based postprandial lipemia measures met the 0.75 criterion for high reproducibility. In general, the TRL triglyceride ICCs were greater for total AUCs, as compared to incremental AUCs, indicating better reproducibility for total AUCs.

Validity of Abbreviated 4-hr Postprandial Lipemia Tests

For total plasma triglycerides, the total and incremental AUCs from the 4-hr tests were highly predictive of the corresponding 8-hr test results, with coefficients of determination (R2) of ~0.90 (Table 5). Likewise, the 4-hr results for TRL triglyceride responses were highly predictive of the 8-hr TRL triglyceride responses with R2 values ≥91%. For comparison purposes, the ability of fasting triglycerides to predict triglyceride AUCs was also assessed (Table 5). Although, fasting triglyceride concentrations were significant predictors of 8-hr AUCs, the R2 values were substantially lower than those for 4-hr AUCs.

Table 5.

Regression equations for predicting triglyceride responses from 8-hr postprandial lipemia tests from 4-hr tests and fasting triglycerides.

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Intercept ± SE | Slope ± SE | R2 | P-value for model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Triglycerides | |||||

| 8-hr total AUC | 4-hr total AUC | −38.7 ± 87.9 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 0.92 | <0.0001 |

| 8-hr total AUC | Fasting TG | 119 ± 239 | 687 ± 258 | 0.50 | 0.03 |

| 8-hr incremental AUC | 4-hr Incremental AUC | −58.2 ± 57.3 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 0.89 | 0.0001 |

| Triglyceride Rich Lipoprotein Triglycerides | |||||

| 8-hr total AUC | 4-hr total AUC | −74.5 ± 43.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 0.96 | <0.0001 |

| 8-hr total AUC | Fasting TRL TG | −84.6 ± 93.0 | 1180.9 ± 206.1 | 0.82 | 0.0007 |

| 8-hr incremental AUC | 4-hr incremental AUC | −48.8 ± 36.5 | 2.6 ± 0.31 | 0.91 | <0.0001 |

Analyses included data from each participant’s first test only. TRL, triglyceride rich lipoprotein.

DISCUSSION

Reproducibility of Total Triglyceride Resonses

Results from the present study demonstrate that the total triglyceride responses during postprandial lipemia tests are highly reproducible in lean and obese subjects, when calculated as the total area under the response curve, and may therefore be of clinical utility for assessing CVD risk. These findings support those of Brown et al. (22) who reported that postprandial total triglyceride concentrations measured 3.5 and 9 hours after a high-fat meal were highly reproducible (ICCs = 0.76 and 0.85, respectively). Gill et al. also found that the total TG responses to a high fat meal were highly reproducible in men (ICC = 0.93) but found more modest reproducibility in young women (ICC = 0.65) if one test was performed during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle and the second test on the same subjects was performed during the luteal phase (23). In light of this finding in women, it is somewhat surprising that reproducibility was high in our study, despite the fact the most of our subjects (78%) were young females and menstrual cycle phase was not measured or controlled for. Furthermore, based on an analysis on women only, total AUC for total triglycerides was highly reproducible (WCV = 7.6%, ICC = 0.85) in our study.

Reproducibility of Incremental and TRL Triglyceride Responses

It is often argued that incremental AUC should be studied instead of total AUC because fasting triglycerides and total AUCs for triglycerides are correlated (24; 25). Furthermore, for a variety of reasons, it may be desirable or necessary to measure TRL triglyceride responses during postprandial lipemia tests. However, to our knowledge, the reproducibility of incremental triglyceride responses and TRL triglyceride responses has not been previously assessed. In contrast to our findings for total AUC for total triglycerides, we found that reproducibility is relatively low when lipemic responses are calculated as incremental areas above baseline or when TRL triglyceride concentrations are measured instead of total triglycerides.

The reason for greater variability in incremental AUCs and TRL-based lipemic responses is not entirely clear. However, this may be partly attributable more sources of measurement error. For the incremental AUCs, fasting triglyceride concentrations are subtracted from postprandial concentrations and as a consequence, this introduces measurement error from the fasting value into the postprandial values. For TRL triglycerides, the additional analytic steps may contribute to greater variability. In either case, it would be expected that with greater analytic precision, the reproducibility of these outcomes would improve. However, until improvements occur, the low reproducibility of incremental and TRL-based measures of postprandial lipemia precludes their use as clinical measures. This does not imply that these measures should not be used for research purposes; however, it may be necessary to use more subjects or use more powerful experimental designs to overcome this variability and avoid type 2 statistical errors (i.e. false negative results).

Validity of Abbreviated 4-hr Postprandial Lipemia Tests

A secondary objective was to determine if an abbreviated 4-hr test could be used to validly predict results from a full-length 8-hr test. Indeed, the lipemic responses from the 4-hr test accounted for 89–96% of the variance in the 8-hr test results. It is important to recognize that this validity assessment does not include day-to-day variability in lipemic responses because the 4-hr test results were derived from the 8-hr test data. However, this approach is appropriate, given that our objective was to compare short and long tests, independent of day-to-day variation in biological function. From a reproducibility perspective, findings from the present study suggest that postprandial lipemia from a 4-hr test are just as reproducible as those from 8-hr tests. Taken together, these findings indicate that an abbreviated 4-hr postprandial lipemia test is a valid and reproducible alternative to full-length tests and may therefore be useful in clinical settings or when large study sample sizes preclude the use of longer tests. Certainly, the 4-hr test is still a considerable time burden for patients or study participants and the evaluation of shorter protocols may be warranted in the future. However, from the perspective of medical expense and time burden on medical personnel, a 4-hr test is reasonable, as it only requires the insertion of an intravenous catheter, administration of the test meal, and the acquisition of hourly blood samples.

Lipemic Responses in Lean versus Obese Individuals

It is somewhat surprising that the lipemic responses were not significantly greater in obese subjects than in lean subjects. However, to avoid the potentially confounding effect of disease treatments (e.g. medications) on the postprandial lipemia reproducibility, we excluded individuals with chronic diseases and as a consequence, may have had obese subjects who were unusually healthy from a metabolic perspective. However, a more likely explanation is that our study was not powered to detect differences between groups. In support of this, it is noteworthy the mean lipemic responses were all ~60% higher in obese subjects than in lean subjects with weak tendencies for significant differences (p = 0.08 – 0.17).

CONCLUSION

Data from the present study show that postprandial lipemia tests are highly reproducible when the total triglyceride response is calculated as total area under the curve. Although there is still a need for meal standardization (i.e. energy and nutrient content) and a need for standards to classify lipemic responses as normal or abnormal, the reproducibility of total triglyceride responses is sufficient for use in a clinical setting. In contrast, when the incremental area under the curve is used, or when TRL triglycerides are used in lieu of total triglycerides, the reproducibility is substantially lower. Unless the variability in these methods for quantifying lipemic responses can be improved, for example through refinement of analytic methods, the large variability in incremental AUCs and TRL triglyceride responses precludes there use for clinical purposes. Finally, results of the present study show that an abbreviated 4-hr postprandial lipemia test is a valid and reproducible surrogate for an 8-hr test.

Table 4.

Intraclass correlation coefficients for the lipemic response to a high fat meal conducted on four different days.

| Lean | Obese | All Subjects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Triglycerides | |||

| Fasting | 0.89 (0.66, 0.99) | 0.88 (0.60, 0.99) | 0.90 (0.76, 0.97) |

| Total AUC | 0.66 (0.25, 0.95) | 0.89 (0.61, 0.99) | 0.82 (0.60, 0.95) |

| Incremental AUC | 0.32 (−0.06, 0.86) | 0.38 (−0.06, 0.92) | 0.36 (0.05, 0.74) |

| 4h total AUC | 0.80 (0.46, 0.97) | 0.93 (0.73, 1.0) | 0.91 (0.78, 0.98) |

| 4h incremental AUC | 0.52 (0.10, 0.92) | 0.83 (0.46, 0.99) | 0.71 (0.42, 0.91) |

| Triglyceride Rich Lipoprotein Triglycerides | |||

| Fasting | 0.82 (0.50, 0.98) | 0.69 (0.23, 0.97) | 0.70 (0.42, 0.91) |

| Total AUC | 0.60 (0.17, 0.94) | 0.49 (0.02, 0.94) | 0.54 (0.22, 0.84) |

| Incremental AUC | 0.42 (0.01, 0.89) | 0.63 (−0.22, 0.81) | 0.28 (−0.02, 0.62) |

| 4h total AUC | 0.76 (0.40, 0.97) | 0.59 (0.11, 0.96) | 0.65 (0.34, 0.89) |

| 4h incremental AUC | 0.60 (0.17, 0.94) | 0.34 (−0.08, 0.92) | 0.50 (0.17, 0.82) |

Data are intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) with 95% confidence interval in parentheses. ICCs with confidence intervals that do not include zero are significantly different from zero. Higher ICC values reflect greater reproducibility; outcomes with values ≥0.75 were considered highly reproducible (20; 21).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the study subjects for their participation in this study and the nursing staff of the General Clinical Research Center for their help in performing tests.

Grant support: This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants DK-37948, HD-0145901, AG-00078, DK-56341 (Clinical Nutrition Research Unit), and RR-00036 (General Clinical Research Center) and a grant from DMV International Corporation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gaenzer H, Sturm W, Neumayr G, et al. Pronounced postprandial lipemia impairs endothelium-dependent dilation of the brachial artery in men. Cardiovasc.Res. 2001;52:509–516. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00427-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teno S, Uto Y, Nagashima H, et al. Association of postprandial hypertriglyceridemia and carotid intima-media thickness in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1401–1406. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeppesen J, Hollenbeck CB, Zhou MY, et al. Relation between insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, postheparin plasma lipoprotein lipase activity, and postprandial lipemia. Arterioscler.Thromb.Vasc.Biol. 1995;15:320–324. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.3.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss EP, Brandauer J, Kulaputana O, et al. FABP2 Ala54Thr genotype is associated with glucoregulatory function and lipid oxidation after a high-fat meal in sedentary nondiabetic men and women. Am.J Clin.Nutr. 2007;85:102–108. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patsch JR, Miesenbock G, Hopferwieser T, et al. Relation of triglyceride metabolism and coronary artery disease. Studies in the postprandial state. Arterioscler.Thromb. 1992;12:1336–1345. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.11.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karpe F. Postprandial lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 1999;246:341–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsetsonis NV, Hardman AE, Mastana SS. Acute effects of exercise on postprandial lipemia: a comparative study in trained and untrained middle-aged women. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 1997;65:525–533. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.2.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weintraub MS, Zechner R, Brown A, et al. Dietary polyunsaturated fats of the W-6 and W-3 series reduce postprandial lipoprotein levels. Chronic and acute effects of fat saturation on postprandial lipoprotein metabolism. J Clin.Invest. 1988;82:1884–1893. doi: 10.1172/JCI113806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parhofer KG, Barrett PH, Schwandt P. Atorvastatin improves postprandial lipoprotein metabolism in normolipidemlic subjects. J Clin.Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4224–4230. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeppesen J, Zhou MY, Chen YD, et al. Effect of metformin on postprandial lipemia in patients with fairly to poorly controlled NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:1093–1099. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.10.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Proctor SD, Mamo JC. Retention of fluorescent-labelled chylomicron remnants within the intima of the arterial wall--evidence that plaque cholesterol may be derived from post-prandial lipoproteins. Eur.J Clin.Invest. 1998;28:497–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1998.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:S37–S42. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.suppl_1.s37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. 1983 Metropolitan Height and Weight Tables. Stat Bull. 1983;64:2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen MD, Heiling VJ. Heated hand vein blood is satisfactory for measurements during free fatty acid kinetic studies. Metabolism. 1991;40:406–409. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(91)90152-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paton CM, Brandauer J, Weiss EP, et al. Hemostatic response to postprandial lipemia before and after exercise training. J.Appl.Physiol. 2006;101:316–321. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01363.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Converse CA, Skinner ER. Lipoprotein Analysis: A Practical Approach. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allison DB, Paultre F, Maggio C, et al. The use of areas under curves in diabetes research. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:245–250. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bland JM, Altman DG. Measurement error proportional to the mean. BMJ. 1996;313:106. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7049.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quan H, Shih WJ. Assessing reproducibility by the within-subject coefficient of variation with random effects models. Biometrics. 1996;52:1195–1203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yvonne-Tee GB, Rasool AH, Halim AS, et al. Reproducibility of different laser Doppler fluximetry parameters of postocclusive reactive hyperemia in human forearm skin. J Pharmacol.Toxicol.Methods. 2005;52:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott DA, Bond EQ, Sisto SA, et al. The intra- and interrater reliability of hip muscle strength assessments using a handheld versus a portable dynamometer anchoring station. Arch Phys.Med Rehabil. 2004;85:598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown SA, Chambless LE, Sharrett AR, et al. Postprandial lipemia: reliability in an epidemiologic field study. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:538–545. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill JM, Malkova D, Hardman AE. Reproducibility of an oral fat tolerance test is influenced by phase of menstrual cycle. Horm.Metab Res. 2005;37:336–341. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nestel PJ. Relationship between plasma triglyceride and removal of chylomicrons. J Clin.Invest. 1964;43:943–949. doi: 10.1172/JCI104980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berglund L. Postprandial lipemia and obesity--any unique features? Am J Clin.Nutr. 2002;76:299–300. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]