Abstract

Despite the pronounced neurological deficits associated with mental retardation and autism, it is unknown if altered neocortical circuit function occurs in these prevalent disorders. Here we demonstrate specific alterations in local synaptic connections, membrane excitability, and circuit activity of defined neuron types in sensory neocortex of the mouse model of Fragile X Syndrome—the Fmr1 knockout (KO). Overall, these alterations result in hyperexcitability of neocortical circuits in the Fmr1 KO. Specifically, we observe a substantial deficit in local excitatory drive (∼50%) targeting fast-spiking (FS) inhibitory neurons in layer 4 of somatosensory, barrel cortex. This persists until at least 4 wk of age suggesting it may be permanent. In contrast, monosynaptic GABAergic synaptic transmission was unaffected. Overall, these changes indicate that local feedback inhibition in neocortical layer 4 is severely impaired in the Fmr1 KO mouse. An increase in the intrinsic membrane excitability of excitatory neurons may further contribute to hyperexcitability of cortical networks. In support of this idea, persistent neocortical circuit activity, or UP states, elicited by thalamic stimulation was longer in duration in the Fmr1 KO mouse. In addition, network inhibition during the UP state was less synchronous, including a 14% decrease in synchrony in the gamma frequency range (30–80 Hz). These circuit changes may be involved in sensory stimulus hypersensitivity, epilepsy, and cognitive impairment associated with Fragile X and autism.

INTRODUCTION

Fragile X syndrome (FXS), the most common form of inherited mental retardation, is caused by loss of function mutations in FMR1 that encodes the RNA binding protein, FMRP (O'Donnell and Warren 2002; Verkerk et al. 1991). Thirty percent of children with FXS are diagnosed with autism and 2–5% of autistic children have FXS, making Fmr1 one of the leading genetic causes of autism (Hagerman et al. 2005; Kaufmann et al. 2004). FXS patients present with a wide range of behavioral and physiological symptoms including cognitive impairment, hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli, epilepsy, and characteristics of autism (Hagerman 2002; Miller et al. 1999). These impairments are reproduced in the FXS mouse model, the Fmr1 knockout (KO) mouse (Bakker 1994; Brennan et al. 2006; Musumeci et al. 2000; Nielsen et al. 2002; Spencer et al. 2005).

It is commonly hypothesized that altered neocortical function mediates the cognitive and behavioral deficits in mental retardation and autism. In support of this idea, cellular and synaptic alterations have been observed in neocortex in FXS patients and in Fmr1 KO mice. Although a number of studies have demonstrated alterations in long-term synaptic plasticity of excitatory synapses in both acute hippocampal and neocortical slices from Fmr1 KO mice, alterations in baseline synaptic function (assessed with extracellular stimulation) were not detected (Desai et al. 2006; Huber et al. 2002; Larson et al. 2005; Li et al. 2002; Wilson and Cox 2007; Zhao et al. 2005). Such “baseline” alterations have been reported in the form of spine shape and density in both patients and Fmr1 mice (Grossman et al. 2006), inhibitory and excitatory neuron synapse markers in Fmr1 KO mice (El Idrissi et al. 2005; Gantois et al. 2006; Li et al. 2002; Selby et al. 2007), and excitatory synapse alterations in cultured hippocampal neurons (Braun and Segal 2000; Hanson and Madison 2007; Pfeiffer and Huber 2007). One very recent report has observed baseline alterations in functional connectivity between layer 4 and layer 2/3 excitatory neurons in the Fmr1 KO, but these disappear by 3 wk of age (Bureau et al. 2008). Therefore it remains unknown if a more persistent deficit in synaptic function exists, and nothing is known about synaptic function onto inhibitory neurons in Fmr1 KO mice.

To better understand FXS, it is important to make a link between electrophysiological alterations at the synaptic and cellular level to alterations in local network function. Such links represent the first step in understanding how cellular alterations relate to the complex neurological symptoms in FXS. One epilepsy paradigm has revealed a plasticity phenomenon where hippocampal networks become more excitable in Fmr1 KO mice (Chuang et al. 2005). However, it is unknown if “baseline” network function under less pathological conditions is altered in Fmr1 KO mice.

We evaluated the local neocortical synaptic connectivity, membrane excitability, and network function under physiological conditions in acute slices from Fmr1 KO mice. In summary, we find alterations consistent with, and that likely lead to, hyperexcitability of neocortical circuits. Furthermore, network synchrony is altered. These findings provide evidence for circuit level alterations underlying neurological deficits associated with FXS and autism.

METHODS

Animals

Animals were all first generation male hybrids obtained by crossing FVB wild-type males and C57Bl/6 heterozygous Fmr1 KO females. Fmr1 KO mice were maintained as a congenic strain on the C57Bl/6 background (Bakker 1994), and FVB mice were the GIN strain (Jackson Laboratories) (Oliva et al. 2000). The GIN strain expresses GFP in a subset of somatostatin-positive (Som+) inhibitory neurons.

Cell identification

Layer 4 fast-spiking (FS) inhibitory neurons and regular spiking excitatory neurons were reliably identified based on firing and synaptic properties (supplementary methods1 ) (Cauli et al. 1997; Connors and Gutnick 1990; Gibson et al. 1999). Most layer 4 excitatory neurons were probably spiny stellate because we targeted smaller, nonpyramidal neurons. When performing morphological measurements on excitatory neurons, 12/14 cells in WT mice and 13/16 in KO mice displayed spiny stellate cell morphology confirming that our excitatory neurons were mostly this type. For layer 2/3 recordings, Som+ neurons were identified by GFP fluorescence and pyramidal neurons by morphology and firing properties.

Electrophysiology

Acute thalamocortical slices were prepared as previously described (Agmon and Connors 1991). Briefly, animals were anesthetized with Euthasol (pentobarbital sodium and phenytoin sodium solution; 2 wk of age) or ketamine (3 and 4 wk of age) and the brain removed following protocols approved by the University of Texas Southwestern. Slices were cut at ∼4°C in dissection buffer, placed in normal artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) at 35°C for 30 min, and slowly cooled to 21°C over the next 45 min. All whole cell recordings were performed in either layer 4 or layer 2/3 of the barrel field in somatosensory cortex. Each recording began with a capacitance measurement and usually a brief examination of action potential firing in response to 600-ms current steps of increasing amplitude. Input resistance and series resistance were constantly monitored (supplementary methods). All data were collected and analyzed using Labview software (National Instruments). Transillumination of the slice under low power, DIC optics allowed us to visualize barrels (Figs. 1 and 7) and reliably confirm that recordings were within a single barrel (Agmon and Connors 1991; Finnerty et al. 1999).

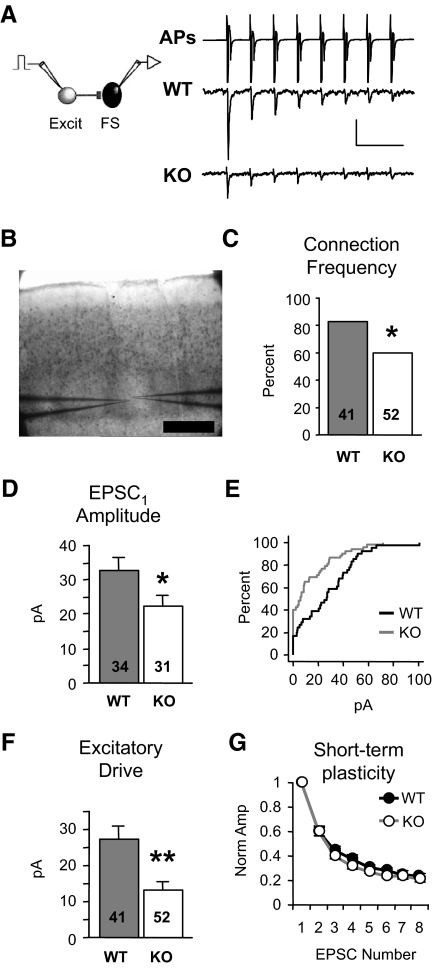

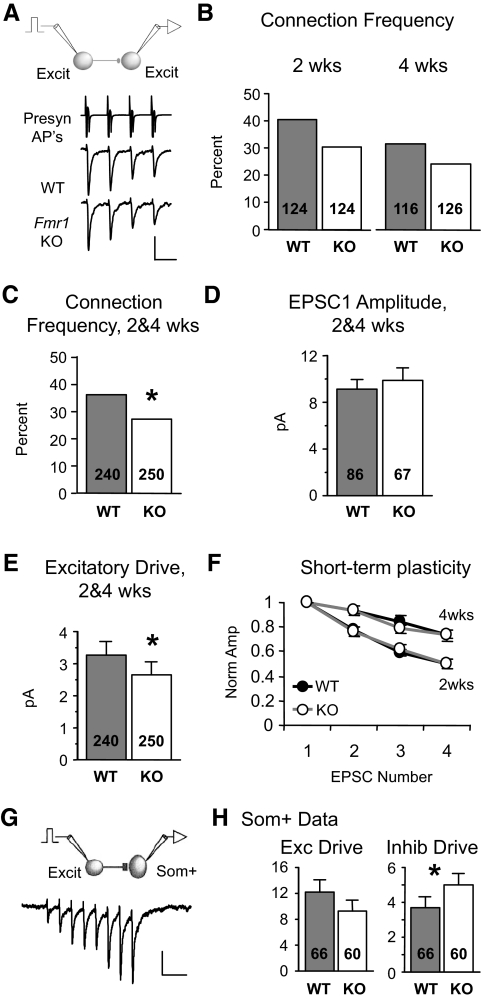

FIG. 1.

Local excitation onto neocortical fast-spiking (FS) inhibitory neurons is dramatically reduced in Fmr1 knockout (KO) mice. A: examples of presynaptic action potentials (APs) being evoked in the excitatory neuron (top, truncated vertically) and resulting unitary excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in layer 4 FS neurons (bottom). APs are elicited in voltage clamp and occur due to voltage escape at the site of AP generation. The waveform of the presynaptic neuron represent the currents generated by the APs. EPSCs are averages from single neurons. Scale bars: vertical, 700 and 10 pA for APs and EPSCs, respectively. Horizontal, 50 ms. B: paired recordings were performed inside layer 4 barrels Scale bar: 250 μm. C: the percentage of synaptically connected excitatory and FS inhibitory neuron pairs is reduced in the KO [χ2; number of total cell pairs tested (n) is indicated in each bar; 34/41 and 31/52, connected/total tested]. D: when a connection existed, average amplitude of EPSC1 (1st EPSC in a train) was significantly decreased in the KO. Number of connected cell pairs (n) is indicated in each bar. E: cumulative distribution of amplitudes, including “nonconnected” pairs (0 pA), from wild-type (WT, black) and KO (gray) mice. F: excitatory drive, the average of both connected and nonconnected pairs, is reduced by 51%. Number of total cell pairs tested (n) is indicated in each bar. G: no change in short-term plasticity of EPSCs was observed (n = 22,16 connected pairs; quantified by an STP index as described in methods). Each EPSC in the train is normalized to EPSC1. *P < 0.03, **P < 0.005. Sample numbers as described in the preceding text apply to similar graphs in subsequent figures. See methods for statistics used.

Electrophysiological solutions

ACSF contained (in mM) 126 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, 25 dextrose, and 2 CaCl2. For UP state experiments, ACSF was altered to better mimic interstitial fluid ionic concentrations in brain (Sanchez-Vives and McCormick 2000; Yamaguchi 1986; Zhang et al. 1990) and contained (in mM): 126 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, 25 dextrose, and 1 CaCl2. All slices were prepared in a sucrose dissection buffer as follows (in mM): 75 sucrose, 87 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 7 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, 20 dextrose, and 0.5 CaCl2. All solutions were pH 7.4. ACSF was saturated with 95% O2-5% CO2. The following pipette solution was used (in mM): 130 K-gluconate, 6 KCl, 3 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 0.2 EGTA, 4 ATP-Mg, 0.3 GTP-Tris, 14 phosphocreatine-Tris, and 10 sucrose (pH 7.25, 290 mosM); for UP state experiments, pipette solution contained the following (in mM): 125 Cs-gluconate, 16 CsCl, 10 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 2.5 bis-(o-aminophenoxy)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA), 4 ATP-Mg, 0.3 GTP-Tris, 14 phosphocreatine-Tris, 10 sucrose, 2 QX-314-Cl, and 10 TEA (pH 7.25, 290 mosM); Measured junction potentials were ∼9 and ∼10 mV, respectively.

Unitary postsynaptic currents (PSCs)

In 300 μm slices obtained from 2-wk (P14-16)- and 4-wk (P25–P31)-old animals, recordings were performed at 21°C using K-gluconate pipette solution. Holding potential was always −65 and −55 mV for excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs and IPSCs), respectively. Presynaptic action potential (AP) trains were eight and four pulses long for FS/Exc and Exc/Exc pairs, respectively (20-Hz train, applied every 8 s). Presynaptic APs were evoked in voltage clamp by a +15- to +30-mV step for 8 ms. Even though the presynaptic cell is voltage clamped, APs still occur because they cannot be clamped in the axon. Therefore the term “action current” more accurately describes the presynaptic traces presented in the figures. Unless stated otherwise, PSC amplitude was based on the first PSC in the train (i.e., EPSC1). A potential unitary connection was considered connected if the average response (based on 25–45 traces) was >2 pA. For short-term plasticity and PSC duration analysis, PSC amplitude met the following criteria (in pA: Ex→FS, >14; FS→Ex, >12; Ex→Ex, >9; Ex→Som, >10; Som→Ex, >2). Short-term plasticity was quantified with an index (STP index) that was PSC1/average(PSC7,PSC8). For Ex→Som, the STP index was average(EPSC1,EPSC2)/average(EPSC7,EPSC8). The “minimal stimulation” protocol applied to thalamic afferents (Fig. 3) was performed as previously described (Gibson et al. 1999) (supplemental methods). See Supplemental Figs. S1–S3 for details of miniature PSC and coefficient of variation analysis. Som+/Exc pairs were only examined at 2 wk of age.

UP states

In 350-μm slices obtained from 3-wk (P19-23)-old animals, simultaneous recordings were performed at 32°C using Cs-gluconate pipette solution. UP states were evoked through stimulation of thalamic afferents with a one- to three-pulse train (40 Hz) using a concentric bipolar electrode (FHC, No. CBBRC75). Thalamic axons were stimulated in the thalamus itself, in the reticular nucleus, and in the internal capsule. Our sample is roughly divided equally among these. Only recordings in which UP states of which had an average duration >100 ms were used for analysis. The onset of an UP state was detected when the amplitude surpassed a threshold in a 100-ms window (thresholds were 100 and 25 pA, for IPSCs and EPSCs, respectively). The end of the UP state was defined by when amplitude decreased back below threshold for >300 ms. The duration of UP states were based on IPSCs. Durations, correlations, power spectra, and amplitude measurements were usually averaged from about five independent traces. The amplitude of PSC barrages was the average amplitude of the barrage during the first 400 ms of the UP state with respect to baseline measured outside of the UP state. Correlations were normalized by dividing the raw correlation by the product of the SD of each trace (Deans et al. 2000). Frequency components and correlations were derived after applying a 20- to 100-Hz band-pass filter (FIR Windowed, 501 taps, Labview). We examined only this frequency range because at frequencies <20 Hz, only approximately four or fewer cycles occur in the shorter UP states of the WT mouse (many were ∼400 ms—the minimum allowed in the correlation analysis). Hence the analysis becomes less reliable at these lower frequencies. All timing analysis was performed on pairs with inhibitory current correlation >0.5, and correlation “width” was the width of the peak in the correlation function measured at 2/3 peak height. The “offset” of the correlation was the location of the peak in the correlation function.

Analysis

Experiments and analysis were performed blind to genotype. Statistical significance was P < 0.05, and all error bars in figures are SE. Statistical comparisons were determined by the unpaired t-test (Mann-Whitney). A χ2 test was applied to determine changes in the percent of connected pairs, and a Fisher's exact P value was used to determine significance. For unitary PSC (percent connected and excitatory drive) and UP state correlation data, sample number (n) is the total number of recorded pairs. For PSC amplitude data, the n represents the number of connected cell pairs. All data presented in the following order: WT, KO.

RESULTS

Local excitation of layer 4 fast-spiking inhibitory neurons is substantially decreased in the Fmr1 KO

To determine how local unitary connections are altered in the Fmr1 KO mouse, we performed simultaneous, paired whole cell recordings of layer 4 neurons in slices of somatosensory neocortex. Recorded neurons were located in the cytoarchitectonic barrel hollows (Fig. 1B). The synaptic connection frequency and strength between cell pairs were measured by recording PSCs in the postsynaptic neuron evoked in response to a train of action potentials elicited in neighboring presynaptic neurons (<20 μm intercellular distance; Fig. 1A). Connections of this type are called “unitary.” Even though the presynaptic cell is voltage clamped, APs still occur because they cannot be clamped in the axon. The term “action current” may more accurately describe the actual presynaptic traces, but we retain the AP label in the figures.

We first examined inhibitory circuitry by recording from pairs of FS inhibitory and regular-spiking excitatory neurons at 2 wk of age (Connors and Gutnick 1990). The frequency of observing EPSCs onto FS neurons was decreased in the KO (connection frequency, Fig. 1C; 83 vs. 60%, P < 0.03). Moreover, when there was a connection, the strength of the connection (amplitude of the 1st EPSC in the train; EPSC1) was decreased (Fig. 1D; 32.9 ± 3.6 vs. 22.1 ± 3.3 pA, P < 0.03). Taking account of both the connection frequency and strength, we calculated the overall local excitatory drive that FS neurons receive by averaging the EPSC amplitudes for both connected and nonconnected cell pairs (0 pA amplitude). Using this measure, the excitatory synaptic drive of FS neurons was reduced by 51% in the KO as shown in the cumulative distributions of EPSC amplitude (Fig. 1E) and group averages (Fig. 1F; 27.3 ± 3.6 vs. 13.2 ± 2.5 pA, P < 0.002). Short-term plasticity was unaltered (STP index, see methods) suggesting that the decrement occurs over a range of firing frequencies and is likely not a result of decreased presynaptic release probability (Fig. 1G) (Watanabe et al. 2005). No change in EPSC duration was observed (Supplementary Table S1). In summary, local excitation onto layer 4 inhibitory neurons is dramatically reduced in a frequency-independent manner in the Fmr1 KO mouse.

Assuming a random targeting of local excitatory synapses onto FS neurons, the decrease in the frequency of unitary connections (Fig. 1C) suggests the decrease in excitatory drive may be largely due to a decrease in synaptic number. To determine if the number of excitatory functional synapses on FS neurons was decreased, we measured both the miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) and coefficient of variation (CV) of EPSC1 in FS neurons. However, all these measurements were unchanged (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2). The lack of change in mEPSC frequency is inconsistent with a global decrease in synapse number. Possible reasons for the lack of any mEPSC change are presented later (see discussion). The lack of change in CV suggests quantal size may be decreased. Therefore the underlying synaptic mechanism for the decreased drive may involve both synapse number and postsynaptic efficacy decreases, but this remains unclear.

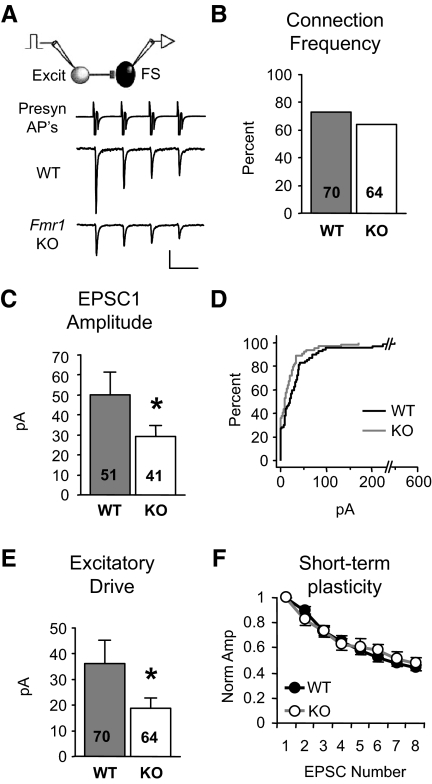

To determine if the impairment in inhibitory circuitry persists in mature mice or is simply due to a developmental delay in synapse formation, we repeated these experiments in slices from older (adolescent; 4 wk) mice. As observed in young KO mice, the excitatory drive targeting FS neurons was decreased by 48% (Fig. 2E; 36.3 ± 8.8 vs. 18.8 ± 3.8 pA, P < 0.04). However, unlike that measured at 2 wk, connection frequency was not detectably different (Fig. 2B), indicating that the major contributor to the excitatory drive deficit in adolescent mice was due to a decrease in EPSC amplitude among existing connections (Fig. 2C; 49.8 ± 11.6 vs. 29.3 ± 5.2 pA, P < 0.04). Again no change was observed in short-term plasticity (Fig. 2F) or EPSC duration (Supplementary Table S2). Therefore, the impaired excitation onto FS neurons in Fmr1 KO mice remains just as severe at this later developmental stage and therefore may be a possible substrate for behavioral and cognitive deficits in mature KO mice and human patients.

FIG. 2.

Deficit in local excitation of FS neurons persists in adolescent Fmr1 KO mice. A: examples of unitary EPSCs targeting layer 4 FS neurons in slices obtained from 4-wk-old animals. Only 1st 4 EPSCs shown. Scale bars: 1,000 and 20 pA, 50 ms. B: no change in connection frequency. C–E: EPSC1 amplitude and drive are decreased while short-term plasticity (F, n = 33,26) is unchanged. *P < 0.04.

Specificity of the excitation impairment of FS inhibitory neurons

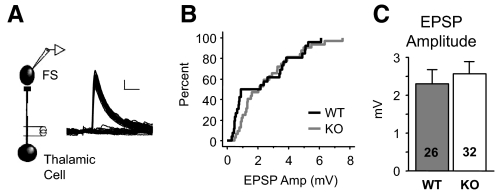

We next tested whether this impaired excitation of FS neurons is specific for locally derived cortical excitatory inputs. FS neurons receive widespread, strong input from the thalamus (Gibson et al. 1999; Sun et al. 2006). Because our slice preparation preserved thalamic afferents, this provided another well-isolated excitatory pathway to examine specificity. Using a “minimal stimulation” protocol to evoke putative unitary EPSPs from individual thalamocortical axons in 2-wk-old animals (methods), we found no difference in thalamically evoked EPSPs onto FS neurons between wild-type (WT) and KO animals, suggesting that the unitary connection strength in this pathway was unaltered (Fig. 3). This result is in contrast to the decrease in EPSC amplitude observed for local cortical afferents (Fig. 1D), indicating that the decrement in excitatory synaptic strength in the Fmr1 KO may be pathway specific and confined to local neuron networks. We were not able to examine connection frequency of thalamic afferents and thus cannot rule out the possibility that excitation is somehow altered in this pathway.

FIG. 3.

Evoked thalamic responses onto FS neurons are unaffected. A: example of thalamically evoked EPSPs in a WT layer 4 FS neuron. A minimal stimulation method was used to obtain a mix of successes and failures of evoked transmission where successes represent putative unitary responses. Scale bars: 1 mV, 5 ms. B and C: summary of minimal stimulation data indicating no change in the cumulative distribution (B) or average EPSP size (C) originating from thalamic afferents. Sample number is stimulus site number obtained from 16 and 20 cells. The numbers in the graph are greater because 2 stimulus sites were examined for a single cell in a subset of recordings.

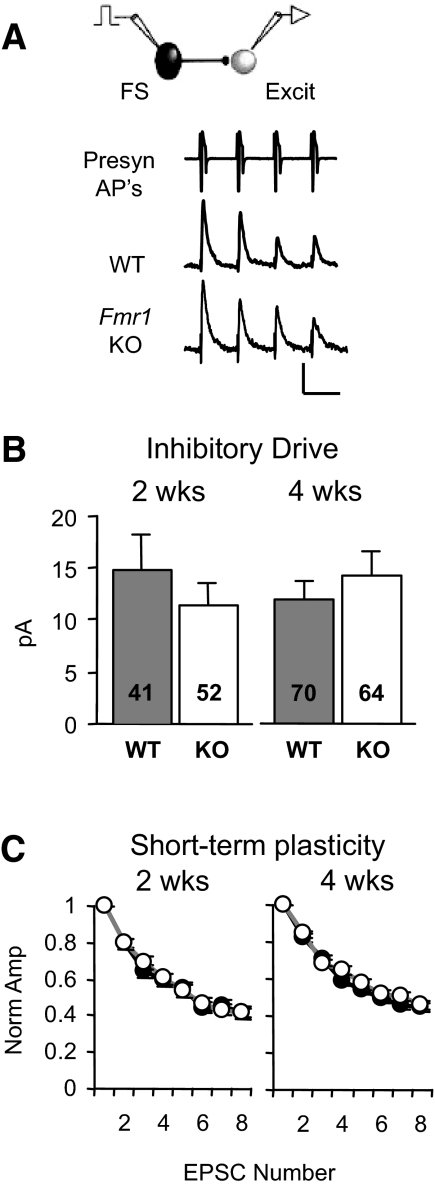

While excitatory drive onto FS neurons was decreased, there was no detectable change in the IPSCs provided by FS neurons onto neighboring excitatory neurons (Fig. 4). Connection frequency and IPSC amplitude were both unaltered at 2 wk (88 vs. 77%, P = 0.28; 17.1 ± 3.7 vs. 15.0 ± 2.3 pA, P = 0.84) and at 4 wk (77 vs. 75%, P = 0.84; 15.3 ± 2.0 vs. 18.7 ± 2.5 pA, P = 0.39). Consequently, no change in inhibitory drive was detected (Fig. 4B; 2 wk, P = 0.50; 4 wk, P = 0.71). Furthermore, there were no changes in short-term plasticity (Fig. 4C) or IPSC duration (Supplementary Table S1, II). These data together with our findings of normal thalamic input to these cells suggest that “feedforward” inhibition is normal. In contrast, the deficit in local excitation onto FS neurons (Figs. 1 and 2) would be predicted to impair disynaptic “feedback” inhibition in Fmr1 KO mice.

FIG. 4.

Inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) originating from FS neurons are unaltered in the Fmr1 KO. A: unitary IPSCs targeting layer 4 excitatory neurons in slices obtained from 2-wk-old animals. Only 1st 4 EPSCs shown. Scale bars: 1,000 and 10 pA, 50 ms. Inhibitory drive (B) and short-term plasticity (C; for 2 wk: n = 14,22; for 4 wk, n = 22,25) are unaltered at both ages.

To determine whether the local excitation impairment is specific to inhibitory neurons, we examined synaptic connectivity and strength among neighboring excitatory neurons (Fig. 5). We found that local excitation onto excitatory neurons was also decreased but to a smaller extent compared with FS inhibitory neurons. Connection frequency was not detectably altered at either 2 or 4 wk of age (Fig. 5B; 2 wk, 40 vs. 30%, P = 0.11; 4 wk, 31 vs. 24%, P = 0.25), but there was a trend toward a decreased connection frequency in the KO at each age. When data were pooled together from the two ages, a small (25%), but significant decrease in connection frequency was observed in the KO (Fig. 5C; 36 vs. 27%, P < 0.04; see supplementary methods for pooling justification). Unlike FS neurons, there was no change in EPSC amplitude at either 2 wk (8.6 ± 1.1 vs. 8.3 ± 1.1 pA, P = 0.73) or 4 wk (9.8 ± 1.4 vs. 11.8 ± 1.9 pA, P = 0.38), or when data from the two ages were pooled (Fig. 5D; 9.1 ± 0.9 vs. 9.9 ± 1.1 pA, P = 0.41). Taking into account both connection frequency and strength across both ages, we observed an 18% decrease in excitatory drive onto excitatory neurons (Fig. 5E; 3.3 ± 0.4 vs. 2.7 ± 0.4 pA, P < 0.05). No change in short-term plasticity (Fig. 5F) or EPSC duration was observed (Supplementary Table S1, II). Like FS neurons, there were no changes in mEPSCs (Supplementary Fig. S3, 2 wks). In conclusion, the decrease in excitatory drive is greater at FS inhibitory neurons compared with excitatory neurons, suggesting that inhibition is more severely compromised in the KO.

FIG. 5.

Local excitation between excitatory neurons is decreased, but to a lesser extent. A: examples of EPSCs targeting layer 4 excitatory neurons in slices obtained from 2-wk-old animals. Scale bars: 1,000 and 10 pA, 50 ms. B: connection frequency was not detectably different at either 2 or 4 wk of age but showed a similar trend. C: connection frequency is decreased in the Fmr1 KO when 2 and 4 wk data are pooled. D: no detectable change in amplitude with pooled data (shown) and unpooled data (not shown). E: excitatory drive is decreased in the KO. F: no change in short-term plasticity with both pooled (not shown) and unpooled data (for 2 wk: n = 20,15; for 4 wk, n = 16,16). Short-term plasticity was dependent on age (P < 0.01). G: example of EPSCs in a WT somatostatin-positive (Som+) inhibitory neuron evoked by a 20-Hz train of action potentials in a presynaptic pyramidal neuron. APs are not shown. Scale bars: 10 pA, 100 ms. H: no difference in local excitatory drive targeting Som+ neurons was detected (left, based on EPSC8), but there was an increase in inhibitory drive provided by Som+ neurons (right). *P < 0.05.

We also examined unitary synaptic connections to and from another inhibitory neuron subtype—those positive for somatostatin (Som+). We performed simultaneous recordings of Som+ inhibitory neurons (identified by GFP expression) (Oliva et al. 2000) and pyramidal neurons (Fig. 5, G and H). Recordings were performed in layer 2/3 because most of the Som+/GFP-expressing neurons were in this layer. Unlike FS inhibitory neurons, all EPSCs targeting Som+ neurons were extremely facilitating during a 20-Hz stimulus train (Fig. 5G) indicative of the Som+ inhibitory subtype (Reyes et al. 1998). Because EPSC1 was not readily detected, we examined the large EPSC8. Unlike layer 4 FS neurons, we found no detectable alterations in unitary excitation of Som+ neurons as observed for excitatory drive (Fig. 5H; 12.2 ± 1.8 vs. 9.3 ± 1.6 pA, P = 0.46). In further contrast to FS neurons, unitary IPSCs mediated by somatostatin-positive neurons actually increased in the KO (Fig. 5H; 3.7 ± 0.6 vs. 5.0 ± 0.7 pA, P < 0.03). No change in short-term plasticity or response kinetics was observed for either synapse. Therefore somatostatin-mediated inhibition is relatively unchanged or even slightly enhanced in the KO. While inhibitory neuron identity is confounded with cortical layer in this comparison, it remains clear that that the changes in layer 4 FS circuitry do not represent a global deficit in all neocortical inhibitory neurons.

Layer 4 excitatory neurons are intrinsically more excitable

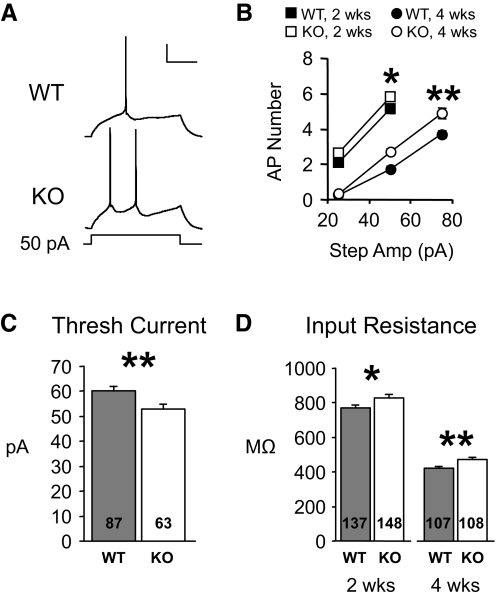

To further understand possible effects of cellular changes on network function, we also determined whether membrane properties of individual neuron types were altered. In excitatory neurons, intrinsic membrane excitability was increased at both experimental ages (Fig. 6). Specifically, they fired more action potentials for a given 600-ms current injection (Fig. 6A). When data were averaged and plotted as number of APs versus current injection, KO neurons fired 20 and 36% more APs at 2 and 4 wk, respectively (Fig. 6B; 2 wk: P < 0.04, n = 61, 70; 4 wk: P < 0.0009; n = 103, 102; repeated-measures ANOVA). Similarly, the minimum current step required to evoke an action potential was decreased in the KO at 4 wk of age (Fig. 6C; current steps were too large to examine this at 2 wk). This excitability alteration is probably due in part to increases in input resistance and decreases in cell capacitance in Fmr1 KO mice (Fig. 6D; Supplementary Table S1, II). However, these membrane changes were not associated with any significant changes in overall dendritic length or branching (Supplementary Fig. S4).

FIG. 6.

Intrinsic membrane excitability of excitatory neurons is increased in Fmr1 KO mice. A: traces from excitatory neurons obtained from 4-wk-old animals showing that for a 50-pA current step, Fmr1 KO cells fire more action potentials. Scale bars: 20 mV, 200 ms. B: average data from 2- and 4-wk data groups showing that more APs occurred for each current step examined. C: in 4 wk cells, the minimum current required to evoke an action potential (threshold current) was decreased in Fmr1 KO mice. D: the increase in membrane excitability may partly be due to an increase in input resistance in Fmr1 KO cells. *P < 0.04. **P < 0.004.

In contrast, there were no significant changes in membrane excitability or firing properties of FS neurons including action potential width. The latter is significant because FMRP binds with high affinity to the mRNA for the voltage-dependent potassium channel, Kv3.1, which is highly expressed in FS neurons and regulates action potential width (Darnell et al. 2001; Erisir et al. 1999) (Supplementary Table S1, II and Supplementary Fig. S5).

UP states are altered in a manner consistent with hyperexcitable circuitry

FS neurons are mostly parvalbumin-positive (Cauli et al. 1997) and comprise ∼50% of all inhibitory neurons in neocortex (Gonchar and Burkhalter 1997). Therefore the impairment in FS-mediated disynaptic inhibition or the increase in the membrane excitability of excitatory neurons, or both, would be expected to increase the excitability of neocortical networks. To test this hypothesis, we examined persistent activity, or “UP” states, in slices from WT and KO mice. UP states refer to short periods of local network activity that generate a steady-state level of depolarization and synchronous firing among groups of neighboring neurons (Sanchez-Vives and McCormick 2000; Steriade et al. 1993). The periodic reoccurrence of UP states in some preparations most closely resembles cortical rhythmic states during relaxed behavioral states and sleep, but they have also been speculated to tap into mechanisms involving short-term memory and attentional states (Cossart et al. 2003; Sanchez-Vives and McCormick 2000). Importantly here, UP states are generated within neocortex through a precise balance of feedback excitation and feedback inhibition. Because we hypothesize that this balance is shifted to more excitation, we predicted to observe greater synaptic excitation during UP states or increased duration of UP states.

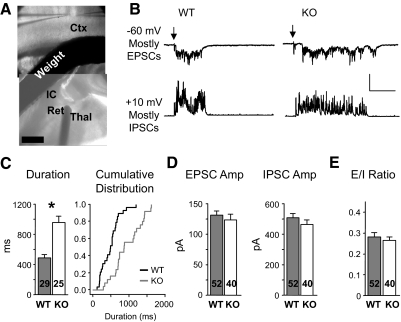

We used extracellular stimulation of thalamocortical afferents to reliably evoke UP states (MacLean et al. 2005; Rigas and Castro-Alamancos 2007) (Fig. 7A). UP states were recorded in layer 4 excitatory neurons in the form of maintained barrages of PSCs. Synaptic currents observed at −60 and +10 mV were predominantly EPSCs and IPSCs, respectively, due to measured reversal potentials. The persistent activity evoked in this paradigm was indeed an UP state (see supplementary methods). While UP states were evoked with the same stimuli (1–3 pulse train at 40 Hz) in both WT and Fmr1 KO slices, UP state duration was increased almost twofold in the Fmr1 KO (Fig. 7C; 487 ± 47 vs. 958 ± 80 ms, P < 0.0001) consistent with greater circuit excitability.

FIG. 7.

Thalamically evoked UP states are longer in duration in the Fmr1 KO. A: picture showing the stimulation and recording configuration. Stimulation of thalamic axons occurred either at the thalamus (Thal), the reticular nucleus (Ret), or the internal capsule (IC). A weight was used to stabilize the experiment. In this example, a stimulation probe is seen in the reticular nucleus. Scale bar: 500 μm. B: single traces showing UP states observed in WT and KO layer 4 excitatory neurons. Each cell had barrages of both EPSCs (−60 mV) and IPSCs (+10 mV) during the UP state. ↓, onset of stimulation (≤3 pulses, 20 Hz). Vertical scale: 200 and 800 pA for −60 and +10, respectively. Horizontal scale: 200 ms. C: average duration of UP states was longer in the KO. Sample number is slice number. Right: the same data plotted as a cumulative distribution. D: EPSC and IPSC average amplitude were unchanged (measured during the 1st 400 ms). Sample number is cell number. E: the EPSC/IPSC amplitude ratio was unchanged. *P < 0.0001.

To determine if the extended UP states in the KO are due to altered synaptic drive, we measured the average amplitude of PSC barrages at −60 and +10 mV during the first 400 ms of the UP state (Fig. 7D). Measurements in this time epoch allowed sufficient data to be analyzed from WT animals. PSC amplitudes were normal in the KO. From this data, we calculated an EPSC/IPSC amplitude ratio (E/I ratio) for each cell, and again, this was not detectably different between genotypes (Fig. 7E). In summary, it was surprising no changes in PSC amplitude were observed, and the exact relationship between our observed cellular changes and longer UP state duration remain unclear (see discussion), but at the very least, both sets of data are consistent with hyperexcitability in network function.

Feedforward inhibition is unaltered in the KO

Because thalamically evoked EPSPs targeting FS neurons and monosynaptic unitary IPSCs supplied by FS neurons are normal in the Fmr1 KO (Figs. 3 and 5), this predicts that both the threshold for evoking an UP state and feedforward inhibition would be unchanged as well. Indeed there was no detectable difference in threshold stimulation applied to thalamic axons to evoke an UP state (Supplementary Fig. S6). To measure feedforward inhibition, we examined disynaptic IPSCs evoked by thalamic stimulation when no UP state was evoked. There was no change in the threshold stimulation strength nor in IPSC amplitude observed at threshold (Supplementary Fig. S7; n = 60, 57; minimal stimulation protocol not used).

Synchrony is altered during UP states

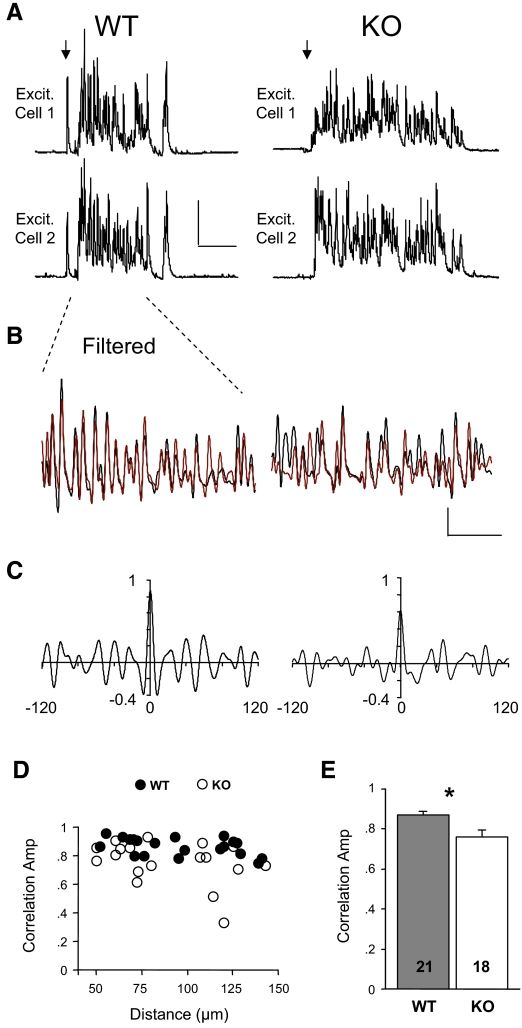

In addition to controlling levels of activity, inhibitory neuron circuits are thought to synchronize action potential firing among cortical neurons during UP states (Hasenstaub et al. 2005). Evidence indicates that the FS subtype is the best candidate to mediate this synchrony (Galarreta and Hestrin 2001; Gibson et al. 2005; Hasenstaub et al. 2005). Based on previous studies, the decrease in excitatory drive onto FS neurons that we found in the KO would be predicted to reduce synchrony in inhibitory circuits (Fuchs et al. 2007). To determine if this was the case, we performed a cross-correlation analysis of IPSCs between simultaneously recorded excitatory neurons of varying distance within the same barrel (Fig. 8). Correlations were performed on the first 400 ms of the UP state. We analyzed currents in the 20- to 100-Hz frequency range, which is thought to largely reflect FS inhibitory neuron activity (Hasenstaub et al. 2005) (also see methods for reasons only examining this range). Cross-correlation peak amplitudes were relatively unchanged at various distances across the barrel in the WT (Fig. 8D). Consistent with altered FS inhibitory circuitry, IPSCs were less synchronous in the Fmr1 KO. The cross-correlation peak amplitude averaged across all inter-cell distances was decreased by 13% in the Fmr1 KO (Fig. 8E; 0.87 ± 0.01 vs. 0.76 ± 0.04, P < 0.004; Fig. 8D). Correlation was reduced to a similar extent when the last 400 ms of UP states were examined (data not shown). Therefore synchrony of IPSCs was clearly impaired over the duration of the UP state. Moreover, when we restricted our analysis to the gamma frequency range (30–80 Hz), we observed a 14% decrease in cross-correlation peak amplitude in the KO (0.88 ± 0.01 vs. 0.76 ± 0.04, P < 0.01; n = 21,18, 1st 400 ms). In contrast, no detectable change in correlation was observed for EPSCs measured at −60 mV (Supplementary Fig. S8), but this signal was smaller and weakly correlated in both genotypes (Hasenstaub et al. 2005).

FIG. 8.

Synchrony of UP states is decreased in Fmr1 KO mice. A: UP states occurring in 2 simultaneously recorded excitatory neurons observed at +10 mV. Scale bars: 500 pA, 250 ms. B: the traces in A are filtered with a 20- to 100-Hz band-pass filter and the 1st 400 ms of the UP states from each cell are superimposed (black and red refer to top and bottom traces, respectively). Scale bars: 200 pA, 100 ms. C: cross-correlograms for the traces in B. D: an average correlogram peak is calculated for each cell pair and plotted against intercellular distance. E: data in D are averaged and reveal a 13% decrease in UP state synchrony in Fmr1 KO slices. *P < 0.004.

While the amount of synchrony was decreased for IPSCs during UP states, the timing of this synchrony was not affected. Both correlation width and offset were unaltered in the KO (width: 4.8 ± 0.08 vs. 4.7 ± 0.07 ms, P = 0.83; offset: 0.14 ± 0.02 vs. 0.22 ± 0.06 ms, P = 0.38; n = 25,17; see methods for width and offset definitions). Remarkably, the submillisecond offset indicates that the IPSC synchrony was practically instantaneous, and this changed little for the longest distances within a barrel (Supplementary Fig. S9). We also measured the correlation between EPSCs measured in one cell and IPSCs measured in another. These signals were inversely correlated with a slight offset indicating a submillisecond delay in the IPSC signal. They were unchanged in the KO (offset: 0.67 ± 0.07 vs. 0.67 ± 0.1 ms, P = 0.92; n = 27, 24).

DISCUSSION

Alterations in the neocortical excitatory/inhibitory balance as well as abnormal neural synchronization have been predicted to contribute to cognitive disorders such as autism (Rubenstein and Merzenich 2003; Uhlhaas and Singer 2006), but data to support these hypotheses are limited. Here we report profound alterations in neocortical layer 4 in the Fmr1 KO mouse at the synaptic, cellular, and network levels. First, decreases in connectivity frequency and strength result in an approximate 50% decrease in excitatory drive onto FS inhibitory neurons. Second, excitatory neurons become intrinsically more excitable in the KO. Overall, these changes would be expected to lead to hyperexcitable circuits; this was confirmed by our finding that UP state duration is doubled in Fmr1 KO mice. Consistent with impaired FS inhibitory circuitry, network synchrony within a single cortical column during the UP state is decreased. The persistence of the inhibitory circuitry and intrinsic excitability deficits at later developmental stages (4 wk of age) indicates that they are correlated with the onset and persistence of cognitive and behavioral dysfunction in FXS (Kau et al. 2002; Rogers et al. 2001).

Circuit hyperexcitability in Fmr1 KO mice

While no change was detected for monosynaptic inhibition provided by FS neurons, the ∼50% decrease in excitatory drive onto FS neurons suggests that local disynaptic inhibition, or feedback inhibition, mediated by FS neurons is dramatically reduced. FS neurons strongly influence circuit function because they comprise approximately ∼50% of all inhibitory neurons and control action potential firing of excitatory neurons due to the targeting of their output to the soma and proximal dendrites (Gonchar and Burkhalter 1997; Miles et al. 1996; Somogyi et al. 1998). Feedback inhibition mediated by Som+ neurons was not decreased, indicating that any hyperexcitability in circuitry selectively involves FS neurons. Because the decrease in excitatory drive is greater at FS inhibitory neurons compared with excitatory neurons, the ratio of recurrent excitation to FS-mediated feedback inhibition may be effectively increased. This ratio is further enhanced by increased membrane excitability of excitatory neurons and perhaps by a previously reported decrease in the density of Parvalbumin+ neurons in layer 4 (>50%) (Selby et al. 2007). Consequently, net recurrent excitation may be increased resulting in a hyperexcitable network. If we consider UP states as a readout of recurrent excitation, prolonged UP states (Fig. 7) reflect this hyperexcitability. A shift to favor recurrent excitation is also consistent with epilepsy and EEG abnormalities associated with FXS (Berry-Kravis 2002; Incorpora et al. 2002; Musumeci et al. 1999). More experiments that directly examine epilepsy and the EEG in Fmr1 KO mice will be needed to provide a stronger link.

Circuit hyperexcitability: link to FXS

FXS patients display hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli from many different modalities (Castren et al. 2003; Hagerman et al. 1991; Miller et al. 1999; Rojas et al. 2001). Similarly, altered auditory prepulse inhibition, increased startle, and audiogenic seizures in the Fmr1 KO mouse also suggest neural sensory responses are augmented (Berry-Kravis 2002; Chen and Toth 2001; Frankland et al. 2004; Nielsen et al. 2002; Spencer et al. 2006). The fact that prolonged UP states are evoked by thalamic axon activation—the primary projection for sensory input into neocortex—suggests our experiments may mimic some aspects of sensory stimulus hypersensitivity. Therefore our data implicate the thalamocortical pathway in sensory hypersensitivity and, more specifically, an impaired balance of excitation and inhibition in neocortical layer 4. UP states may also occur independently of sensory input and may amplify sensory input by some independent process such as attention (Haider et al. 2007; Rosanova and Timofeev 2005). Consequently, their longer duration in KO mice may increase the likelihood of enhanced responses.

Because UP states in cortical slices maintained in interface chambers occur spontaneously at a slow rate (<1 Hz) and all neurons in a cortical region appear to enter UP states simultaneously, this process in acute slices is hypothesized to be related to the synchronized activity of cortical neurons mediating slow oscillations during quiescence or sleep (Crochet and Petersen 2006; Rigas and Castro-Alamancos 2007; Sanchez-Vives and McCormick 2000; Steriade 1997). Interestingly, lower-frequency components of the EEG are enhanced in 20–50% of FXS patients (Sabaratnam et al. 2001), but because we have not measured the spontaneous occurrence of UP states in this study, it is difficult to determine how the longer UP states we observe relate to this abnormal EEG. Slow oscillations during sleep have been implicated in memory consolidation (Marshall et al. 2006). Therefore if our observations of altered UP states underlie possible changes in slow oscillations, they could be related to cognitive disabilities in FXS patients.

Ultimately, the changes in excitability and UP state properties may have many effects. Abnormal layer 4 processing of sensory input or reduced FS-mediated inhibition in Fmr1 KO mice may impede normal sensory-driven maturation of cortical circuits as well as sensory processing in the adult (Hensch 2005; Miller et al. 2001). And, assuming our observed changes in layer 4 of primary somatosensory cortex also occur in other layers and in higher order neocortical regions, they could greatly contribute to the cognitive and behavioral deficits in FXS.

Excitatory synaptic deficits in FXS

The first suggestion that FXS may have a synaptic etiology came from findings of elevated and elongated dendritic spines on layer 5 neocortical neurons in both FXS patients and adult Fmr1 KO mice (reviewed in Grossman et al. 2006). Here we observed a large decrease in evoked excitatory synaptic connectivity onto FS inhibitory neurons that are mostly aspiny (sometimes “sparsely” spiny) and practically all excitatory synapses target their dendritic shafts (Connors and Gutnick 1990; Keller and White 1987). Importantly, this indicates that FMRP may regulate synaptic function and development independent of spine number and structure.

Recent work in cultured hippocampal slices have reported altered excitatory synaptic function as a result of FMRP deletion (Hanson and Madison 2007; Pfeiffer and Huber 2007). However, these studies do not address the actual state of neural circuits in the disease model (the Fmr1 KO) and had to use a mosaic expression pattern of FMRP to detect synaptic changes. Most attempts to observe functional synaptic alterations in acute slices obtained from Fmr1 KO mice have failed (Desai et al. 2006; Huber et al. 2002; Larson et al. 2005; Li et al. 2002; Wilson and Cox 2007; Zhao et al. 2005), but a recent study mapping layer 4 excitation of layer 2/3 excitatory neurons did observe a transient deficit that disappeared at 3 wk of age (Bureau et al. 2008). Here we observed robust changes in excitatory synaptic function onto FS inhibitory neurons and in excitability of excitatory neurons that persist until at least 4 wk of age.

The effects we observe may be due to a cell autonomous function of FMRP in neocortical neurons or a secondary consequence as a result of loss of FMRP in other brain regions. Excitatory cortical neurons as well as parvalbumin-positive inhibitory neurons (the likely biochemical type of most FS cells in this study) express Fmr1 mRNA and FMRP (Feng et al. 1997; Irwin et al. 2000; Sugino et al. 2006) (http://mouse.bio.brandeis.edu/) (our unpublished observations), suggesting that FMRP may function directly in either excitatory and/or inhibitory neocortical neurons to regulate synaptic connectivity. Several studies have implicated postsynaptic FMRP in synapse elimination (Pan et al. 2004; Pfeiffer and Huber 2007; Zhang et al. 2001). The site of FMRP function in relation to our data are unresolved, but our results are consistent with another study using paired recordings of CA3 neurons in cultured slices that reported a decrease in synaptic connectivity with presynaptic deletion of Fmr1 (Hanson and Madison 2007). Therefore FMRP appears to regulate multiple synaptic parameters that may depend on cell type, developmental age, or the synaptic locus of FMRP expression.

Acute expression of FMRP can control excitatory synapse number (Pfeiffer and Huber 2007). The observed decrease in connectivity frequency without any detectable changes in short-term plasticity (Fig. 1, C and G) suggests that there are fewer synapses mediating local excitation of FS neurons in the KO but that the remaining synapses have normal presynaptic release probability (Watanabe et al. 2005). However, the fact that mEPSC frequency was unchanged suggests that there was not an overall decrease in excitatory synapse number. Synaptic inputs originating from more distant cells may elaborate to maintain a sufficient synapse number on FS neurons and may obscure the contribution of local synaptic connections to mEPSCs. Alternatively, there could be a specific deficit in evoked synaptic transmission which occurs independently of changes in spontaneous synaptic transmission (Calakos et al. 2004; Geppert et al. 1994; Sara et al. 2005). We were unable to detect changes in CV, suggesting that decreased quantal amplitude may underlie the decrease in excitatory drive onto FS neurons, but this is not consistent with either the decrease in connection frequency (Figs. 1C and 2B) or the lack of change in mEPSC amplitude. Our CV measure may have been compromised by the high rate of spontaneous EPSCs known to occur in FS neurons (Galarreta and Hestrin 1999). Therefore the synaptic basis for the decrease in drive remains unclear.

Circuit mechanisms of altered UP states in the Fmr1 KO

Inhibitory synaptic currents during UP states were less synchronous between neurons in the KO, which is likely due to the observed decrease in excitation of FS neurons (Figs. 1, 2, and 8). FS neurons are thought to be the main mediators of inhibitory input in the gamma frequency range that we measured during UP states (Fuchs et al. 2007; Hasenstaub et al. 2005; Whittington and Traub 2003). Previous reports have shown that the excitation of FS neurons promotes network synchrony (Fuchs et al. 2007; Galarreta and Hestrin 2001; Traub et al. 1996), and therefore decreased excitation of FS neurons would be expected to result in less gamma synchrony. Because we have not measured synchrony at other frequency ranges, it is unknown if the synchrony deficit is specific for the gamma range. Nevertheless, the observed 14% decrease in gamma synchrony is consistent with an excitation deficit at FS neurons.

Because UP states originate and are controlled within cortex (MacLean et al. 2005; Sanchez-Vives and McCormick 2000; Steriade 1997), it is likely that the increased UP state duration observed in Fmr1 KO is due to intracortical mechanisms. In support of this assertion, we performed preliminary experiments in KO slices with the thalamus removed, and a similar trend toward longer UP states was observed (data not shown). However, because we did not observe robust differences in PSC amplitudes during UP states in Fmr1 KO mice (Fig. 7), the contribution of altered synaptic drive to prolonged UP states remains unclear. One possibility for the lack of PSC amplitude changes is that decreases in IPSCs from FS neurons may be compensated by increased IPSC drive from other inhibitory neuron types, such as from Som+ neurons (Fig. 5H). While such compensation may increase IPSC amplitude, it may not provide the type of inhibition needed to stop action potential generation during the UP state. Another possibility for unaltered PSC amplitude changes is that the increased intrinsic excitability of excitatory neurons and the decreased unitary EPSCs among excitatory neurons may compensate for and offset the decrease in disynaptic inhibition provided by FS neurons, thereby homeostatically maintaining the appropriate PSC amplitude during the UP state.

It is possible that decreased FS- mediated IPSC synchrony could lead to prolonged UP states in KO neurons (Fig. 8). With decreased inhibitory current synchrony, average network inhibition may be unchanged, but the instantaneous peaks in total network inhibition (hypothetically measured over many cells simultaneously) would be expected to decrease. As a result, in Fmr1 KO mice, the periodic maxima in network inhibition are not strong enough to stop the UP state until much later when network excitation has subsided. Experimental and theoretical evidence suggests that FS activity is involved in terminating UP states (Brunel and Wang 2001; Shu et al. 2003).

Ultimately, because the cellular mechanisms that mediate UP states are not entirely understood even in WT cortex, additional experiments are required to determine the relationship between cellular and synaptic alterations and longer UP states in Fmr1 KO mice.

Relevance to autism

Because ≤30% of FXS patients are diagnosed with autism, Fmr1 KO mice may also be considered a genetic model for autism (Hagerman et al. 2005). With this in mind, our results support the assertion that altered network synchrony may underlie certain aspects of autism (Uhlhaas and Singer 2006; Wilson et al. 2007). Our results also support the idea that increases in the E/I ratio in cortex underlie the neurological deficits in many forms of autism (Rubenstein and Merzenich 2003). Altered E/I ratios have also been reported in other animal models of autism such as the Rett Syndrome and neuroligin 3 mutation mouse models, but in contrast to Fmr1 KO, are decreased (Chubykin et al. 2007; Dani et al. 2005). However, any change in the balance of excitation to inhibition may result in altered UP states or synchrony. It will be important to analyze such dynamic network properties in these autism models.

GRANTS

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health Grants NS-045711 and HD-052731 (K. M. Huber), the Autism Speaks and FRAXA Research Foundations (J. R. Gibson, K. M. Huber).

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Loerwald for assistance in genotyping.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental data.

REFERENCES

- Agmon and Connors 1991.Agmon A, Connors BW. Thalamocortical responses of mouse somatosensory (barrel) cortex in vitro. Neuroscience 41: 365–379, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker 1994.Bakker DB Fmr1 knockout mice: a model to study fragile X mental retardation. The Dutch-Belgian Fragile X Consortium. Cell 78: 23–33, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry-Kravis 2002.Berry-Kravis E Epilepsy in fragile X syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 44: 724–728, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun and Segal 2000.Braun K, Segal M. FMRP involvement in formation of synapses among cultured hippocampal neurons. Cereb Cortex 10: 1045–1052, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan et al. 2006.Brennan FX, Albeck DS, Paylor R. Fmr1 knockout mice are impaired in a leverpress escape/avoidance task. Genes Brain Behav 5: 467–471, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunel and Wang 2001.Brunel N, Wang XJ. Effects of neuromodulation in a cortical network model of object working memory dominated by recurrent inhibition. J Comput Neurosci 11: 63–85, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau et al. 2008.Bureau I, Shepherd GM, Svoboda K. Circuit and plasticity defects in the developing somatosensory cortex of FMR1 knock-out mice. J Neurosci 28: 5178–5188, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calakos et al. 2004.Calakos N, Schoch S, Sudhof TC, Malenka RC. Multiple roles for the active zone protein RIM1alpha in late stages of neurotransmitter release. Neuron 42: 889–896, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castren et al. 2003.Castren M, Paakkonen A, Tarkka IM, Ryynanen M, Partanen J. Augmentation of auditory N1 in children with fragile X syndrome. Brain Topogr 15: 165–171, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauli et al. 1997.Cauli B, Audinat E, Lambolez B, Angulo MC, Ropert N, Tsuzuki K, Hestrin S, Rossier J. Molecular and physiological diversity of cortical nonpyramidal cells. J Neurosci 17: 3894–3906, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen and Toth 2001.Chen L, Toth M. Fragile X mice develop sensory hyperreactivity to auditory stimuli. Neuroscience 103: 1043–1050, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang et al. 2005.Chuang SC, Zhao W, Bauchwitz R, Yan Q, Bianchi R, Wong RK. Prolonged epileptiform discharges induced by altered group I metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated synaptic responses in hippocampal slices of a fragile X mouse model. J Neurosci 25: 8048–8055, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubykin et al. 2007.Chubykin AA, Atasoy D, Etherton MR, Brose N, Kavalali ET, Gibson JR, Sudhof TC. Activity-dependent validation of excitatory versus inhibitory synapses by neuroligin-1 versus neuroligin-2. Neuron 54: 919–931, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors and Gutnick 1990.Connors BW, Gutnick MJ. Intrinsic firing patterns of diverse neocortical neurons. Trends Neurosci 13: 99–104, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossart et al. 2003.Cossart R, Aronov D, Yuste R. Attractor dynamics of network UP states in the neocortex. Nature 423: 283–288, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crochet and Petersen 2006.Crochet S, Petersen CC. Correlating whisker behavior with membrane potential in barrel cortex of awake mice. Nat Neurosci 9: 608–610, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani et al. 2005.Dani VS, Chang Q, Maffei A, Turrigiano GG, Jaenisch R, Nelson SB. Reduced cortical activity due to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition in a mouse model of Rett Syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 12560–12565, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell et al. 2001.Darnell JC, Jensen KB, Jin P, Brown V, Warren ST, Darnell RB. Fragile X mental retardation protein targets G quartet mRNAs important for neuronal function. Cell 107: 489–499, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans et al. 2001.Deans MR, Gibson JR, Sellitto C, Connors BW, Paul DL. Synchronous activity of inhibitory networks in neocortex requires electrical synapses containing connexin36. Neuron 31: 477, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai et al. 2006.Desai NS, Casimiro TM, Gruber SM, Vanderklish PW. Early postnatal plasticity in neocortex of FMR1 knockout mice. J Neurophysiol 96: 1734–1745, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Idrissi et al. 2005.El Idrissi A, Ding XH, Scalia J, Trenkner E, Brown WT, Dobkin C. Decreased GABA(A) receptor expression in the seizure-prone fragile X mouse. Neurosci Lett 377: 141–146, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erisir et al. 1999.Erisir A, Lau D, Rudy B, Leonard CS. Function of specific K(+) channels in sustained high-frequency firing of fast-spiking neocortical interneurons. J Neurophysiol 82: 2476–2489, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng et al. 1997.Feng Y, Gutekunst CA, Eberhart DE, Yi H, Warren ST, Hersch SM. Fragile X mental retardation protein: nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and association with somatodendritic ribosomes. J Neurosci 17: 1539–1547, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerty et al. 1999.Finnerty GT, Roberts LS, Connors BW. Sensory experience modifies the short-term dynamics of neocortical synapses. Nature 400: 367–371, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankland et al. 2004.Frankland PW, Wang Y, Rosner B, Shimizu T, Balleine BW, Dykens EM, Ornitz EM, Silva AJ. Sensorimotor gating abnormalities in young males with fragile X syndrome and Fmr1-knockout mice. Mol Psychiatry 9: 417–425, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs et al. 2007.Fuchs EC, Zivkovic AR, Cunningham MO, Middleton S, Lebeau FE, Bannerman DM, Rozov A, Whittington MA, Traub RD, Rawlins JN, Monyer H. Recruitment of parvalbumin-positive interneurons determines hippocampal function and associated behavior. Neuron 53: 591–604, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta and Hestrin 1999.Galarreta M, Hestrin S. A network of fast-spiking cells in the neocortex connected by electrical synapses. Nature 402: 72–75, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta and Hestrin 2001.Galarreta M, Hestrin S. Spike transmission and synchrony detection in networks of GABAergic interneurons. Science 292: 2295–2299, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantois et al. 2006.Gantois I, Vandesompele J, Speleman F, Reyniers E, D'Hooge R, Severijnen LA, Willemsen R, Tassone F, Kooy RF. Expression profiling suggests underexpression of the GABA(A) receptor subunit delta in the fragile X knockout mouse model. Neurobiol Dis 21: 346–357, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppert et al. 1994.Geppert M, Goda Y, Hammer RE, Li C, Rosahl TW, Stevens CF, Sudhof TC. Synaptotagmin I: a major Ca2+ sensor for transmitter release at a central synapse. Cell 79: 717–727, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson et al. 2005.Gibson JR, Beierlein M, Connors BW. Functional properties of electrical synapses between inhibitory interneurons of neocortical layer 4. J Neurophysiol 93: 467–480, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson et al. 1999.Gibson JR, Beierlein M, Connors BW. Two networks of electrically coupled inhibitory neurons in neocortex. Nature 402: 75–79, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonchar and Burkhalter 1997.Gonchar Y, Burkhalter A. Three distinct families of GABAergic neurons in rat visual cortex. Cereb Cortex 7: 347–358, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman et al. 2006.Grossman AW, Aldridge GM, Weiler IJ, Greenough WT. Local protein synthesis and spine morphogenesis: fragile X syndrome and beyond. J Neurosci 26: 7151–7155, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman 2002.Hagerman R The physical and behavioral phenotype. In: Fragile X Syndrome: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Research, edited by Hagerman R, and Hagerman P. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002, p. 3–109.

- Hagerman et al. 1991.Hagerman RJ, Amiri K, Cronister A. Fragile X checklist. Am J Med Genet 38: 283–287, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman et al. 2005.Hagerman RJ, Ono MY, Hagerman PJ. Recent advances in fragile X: a model for autism and neurodegeneration. Curr Opin Psychiatry 18: 490–496, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider et al. 2007.Haider B, Duque A, Hasenstaub AR, Yu Y, McCormick DA. Enhancement of visual responsiveness by spontaneous local network activity in vivo. J Neurophysiol 97: 4186–4202, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson and Madison 2007.Hanson JE, Madison DV. Presynaptic FMR1 genotype influences the degree of synaptic connectivity in a mosaic mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci 27: 4014–4018, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenstaub et al. 2005.Hasenstaub A, Shu Y, Haider B, Kraushaar U, Duque A, McCormick DA. Inhibitory postsynaptic potentials carry synchronized frequency information in active cortical networks. Neuron 47: 423–435, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch 2005.Hensch TK Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 877–888, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber et al. 2002.Huber KM, Gallagher SM, Warren ST, Bear MF. Altered synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X mental retardation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 7746–7750, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incorpora et al. 2002.Incorpora G, Sorge G, Sorge A, Pavone L. Epilepsy in fragile X syndrome. Brain Dev 24: 766–769, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin et al. 2000.Irwin SA, Galvez R, Greenough WT. Dendritic spine structural anomalies in fragile-X mental retardation syndrome. Cereb Cortex 10: 1038–1044, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kau et al. 2002.Kau AS, Meyer WA, Kaufmann WE. Early development in males with Fragile X syndrome: a review of the literature. Microsc Res Tech 57: 174–178, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann et al. 2004.Kaufmann WE, Cortell R, Kau AS, Bukelis I, Tierney E, Gray RM, Cox C, Capone GT, Stanard P. Autism spectrum disorder in fragile X syndrome: communication, social interaction, and specific behaviors. Am J Med Genet A 129: 225–234, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller and White 1987.Keller A, White EL. Synaptic organization of GABAergic neurons in the mouse SmI cortex. J Comp Neurol 262: 1–12, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson et al. 2005.Larson J, Jessen RE, Kim D, Fine AK, du Hoffmann J. Age-dependent and selective impairment of long-term potentiation in the anterior piriform cortex of mice lacking the fragile X mental retardation protein. J Neurosci 25: 9460–9469, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. 2002.Li J, Pelletier MR, Perez Velazquez JL, Carlen PL. Reduced cortical synaptic plasticity and GluR1 expression associated with fragile X mental retardation protein deficiency. Mol Cell Neurosci 19: 138–151, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean et al. 2005.MacLean JN, Watson BO, Aaron GB, Yuste R. Internal dynamics determine the cortical response to thalamic stimulation. Neuron 48: 811–823, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall et al. 2006.Marshall L, Helgadottir H, Molle M, Born J. Boosting slow oscillations during sleep potentiates memory. Nature 444: 610–613, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles et al. 1996.Miles R, Toth K, Gulyas AI, Hajos N, Freund TF. Differences between somatic and dendritic inhibition in the hippocampus. Neuron 16: 815–823, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller et al. 2001.Miller KD, Pinto DJ, Simons DJ. Processing in layer 4 of the neocortical circuit: new insights from visual and somatosensory cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol 11: 488–497, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller et al. 1999.Miller LJ, McIntosh DN, McGrath J, Shyu V, Lampe M, Taylor AK, Tassone F, Neitzel K, Stackhouse T, Hagerman RJ. Electrodermal responses to sensory stimuli in individuals with fragile X syndrome: a preliminary report. Am J Med Genet 83: 268–279, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musumeci et al. 2000.Musumeci SA, Bosco P, Calabrese G, Bakker C, De Sarro GB, Elia M, Ferri R, Oostra BA. Audiogenic seizures susceptibility in transgenic mice with fragile X syndrome. Epilepsia 41: 19–23, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musumeci et al. 1999.Musumeci SA, Hagerman RJ, Ferri R, Bosco P, Dalla Bernardina B, Tassinari CA, De Sarro GB, Elia M. Epilepsy and EEG findings in males with fragile X syndrome. Epilepsia 40: 1092–1099, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen et al. 2002.Nielsen DM, Derber WJ, McClellan DA, Crnic LS. Alterations in the auditory startle response in Fmr1 targeted mutant mouse models of fragile X syndrome. Brain Res 927: 8–17, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell and Warren 2002.O'Donnell WT, Warren ST. A decade of molecular studies of fragile X syndrome. Annu Rev Neurosci 25: 315–338, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva et al. 2000.Oliva AA, Jiang M, Lam T, Smith KL, Swann JW. Novel hippocampal interneuronal subtypes identified using transgenic mice that express green fluorescent protein in GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci 20: 3354–3368, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan et al. 2004.Pan L, Zhang YQ, Woodruff E, Broadie K. The Drosophila fragile X gene negatively regulates neuronal elaboration and synaptic differentiation. Curr Biol 14: 1863–1870, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer and Huber 2007.Pfeiffer BE, Huber KM. Fragile X mental retardation protein induces synapse loss through acute postsynaptic translational regulation. J Neurosci 27: 3120–3130, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes et al. 1998.Reyes A, Lujan R, Rozov A, Burnashev N, Somogyi P, Sakmann B. Target-cell-specific facilitation and depression in neocortical circuits. Nature Neurosci 1: 279–285, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigas and Castro-Alamancos 2007.Rigas P, Castro-Alamancos MA. Thalamocortical Up states: differential effects of intrinsic and extrinsic cortical inputs on persistent activity. J Neurosci 27: 4261–4272, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers et al. 2001.Rogers SJ, Wehner DE, Hagerman R. The behavioral phenotype in fragile X: symptoms of autism in very young children with fragile X syndrome, idiopathic autism, and other developmental disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr 22: 409–417, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas et al. 2001.Rojas DC, Benkers TL, Rogers SJ, Teale PD, Reite ML, Hagerman RJ. Auditory evoked magnetic fields in adults with fragile X syndrome. Neuroreport 12: 2573–2576, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosanova and Timofeev 2005.Rosanova M, Timofeev I. Neuronal mechanisms mediating the variability of somatosensory evoked potentials during sleep oscillations in cats. J Physiol 562: 569–582, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein and Merzenich 2003.Rubenstein JL, Merzenich MM. Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav 2: 255–267, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabaratnam et al. 2001.Sabaratnam M, Vroegop PG, Gangadharan SK. Epilepsy and EEG findings in 18 males with fragile X syndrome. Seizure 10: 60–63, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vives and McCormick 2000.Sanchez-Vives MV, McCormick DA. Cellular and network mechanisms of rhythmic recurrent activity in neocortex. Nat Neurosci 3: 1027–1034, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sara et al. 2005.Sara Y, Virmani T, Deak F, Liu X, Kavalali ET. An isolated pool of vesicles recycles at rest and drives spontaneous neurotransmission. Neuron 45: 563–573, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby et al. 2007.Selby L, Zhang C, Sun QQ. Major defects in neocortical GABAergic inhibitory circuits in mice lacking the fragile X mental retardation protein. Neurosci Lett 412: 227–232, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu et al. 2003.Shu Y, Hasenstaub A, McCormick DA. Turning on and off recurrent balanced cortical activity. Nature 423: 288–293, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi et al. 1998.Somogyi P, Tamas G, Lujan R, Buhl EH. Salient features of synaptic organisation in the cerebral cortex. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 26: 113–135, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer et al. 2005.Spencer CM, Alekseyenko O, Serysheva E, Yuva-Paylor LA, Paylor R. Altered anxiety-related and social behaviors in the Fmr1 knockout mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Genes Brain Behav 4: 420–430, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer et al. 2006.Spencer CM, Serysheva E, Yuva-Paylor LA, Oostra BA, Nelson DL, Paylor R. Exaggerated behavioral phenotypes in Fmr1/Fxr2 double knockout mice reveal a functional genetic interaction between Fragile X-related proteins. Hum Mol Genet 15: 1984–1994, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade 1997.Steriade M Synchronized activities of coupled oscillators in the cerebral cortex and thalamus at different levels of vigilance. Cereb Cortex 7: 583–604, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade et al. 1993.Steriade M, McCormick DA, Sejnowski TJ. Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain. Science 262: 679–685, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugino et al. 2006.Sugino K, Hempel CM, Miller MN, Hattox AM, Shapiro P, Wu C, Huang ZJ, Nelson SB. Molecular taxonomy of major neuronal classes in the adult mouse forebrain. Nat Neurosci 9: 99–107, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun et al. 2006.Sun QQ, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Barrel cortex microcircuits: thalamocortical feedforward inhibition in spiny stellate cells is mediated by a small number of fast-spiking interneurons. J Neurosci 26: 1219–1230, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub et al. 1996.Traub RD, Whittington MA, Stanford IM, Jefferys JG. A mechanism for generation of long-range synchronous fast oscillations in the cortex. Nature 383: 621–624, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas and Singer 2006.Uhlhaas PJ, Singer W. Neural synchrony in brain disorders: relevance for cognitive dysfunctions and pathophysiology. Neuron 52: 155–168, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk et al. 1991.Verkerk AJ, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Fu YH, Kuhl DP, Pizzuti A, Reiner O, Richards S, Victoria MF, Zhang FP, Eussen BE, van Ommen GB, Blonden LAJ, Riggins GJ, Chastain JL, Kunst CB, Galjaard H, Caskey CT, Nelson DL, Oostra BA, Warren ST. Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell 65: 905–914, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe et al. 2005.Watanabe J, Rozov A, Wollmuth LP. Target-specific regulation of synaptic amplitudes in the neocortex. J Neurosci 25: 1024–1033, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington and Traub 2003.Whittington MA, Traub RD. Interneuron diversity series: inhibitory interneurons and network oscillations in vitro. Trends Neurosci 26: 676–682, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson and Cox 2007.Wilson BM, Cox CL. Absence of metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated plasticity in the neocortex of fragile X mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 2454–2459, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson et al. 2007.Wilson TW, Rojas DC, Reite ML, Teale PD, Rogers SJ. Children and adolescents with autism exhibit reduced MEG steady-state gamma responses. Biol Psychiatry 62: 192–197, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi 1986.Yamaguchi T Cerebral extracellular potassium concentration change and cerebral impedance change in short-term ischemia in gerbil. Bull Tokyo Med Dent Univ 33: 1–8, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. 1990.Zhang ET, Hansen AJ, Wieloch T, Lauritzen M. Influence of MK-801 on brain extracellular calcium and potassium activities in severe hypoglycemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 10: 136–139, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. 2001.Zhang YQ, Bailey AM, Matthies HJ, Renden RB, Smith MA, Speese SD, Rubin GM, Broadie K. Drosophila fragile X-related gene regulates the MAP1B homolog Futsch to control synaptic structure and function. Cell 107: 591–603, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao et al. 2005.Zhao MG, Toyoda H, Ko SW, Ding HK, Wu LJ, Zhuo M. Deficits in trace fear memory and long-term potentiation in a mouse model for fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci 25: 7385–7392, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]