Abstract

Objectives:

In this paper we focus on governance and the added value of regionalization in the context of health policy implementation.

What are regional boards’ patterns of action in the governance process?

How do these patterns favour policy implementation?

Analytical framework:

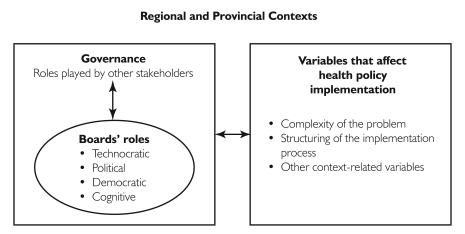

To enhance our understanding of the role of regional boards in governance processes, we relied on four conceptual constructs that corresponded to models of collective action: political, technocratic, democratic and cognitive.

Alongside the four models, we analyzed the impact of governance on health policy implementation using Mazmanian and Sabatier’s general analytical framework, which identifies three types of variables that affect public policy implementation: (1) variables related to the complexity of the problem, (2) statutory variables that structure the implementation of the policy and (3) non-statutory variables related to the context.

Methods:

We conducted a qualitative, longitudinal case study of the regional implemention of the Program to Combat Cancer in Quebec.

Findings:

This research stresses the added value of a clinico-administrative governance of change, whereby regional boards, in synergy with clinical leaders, participate in the orientation of collective action. Analysis of the regional board’s patterns of action reveals the utility of combined technocratic, democratic, political and cognitive actions.

Abstract

Objectifs :

Le présent article porte sur la gouvernance et la valeur ajoutée de la régionalisation dans le contexte de l’application des politiques de santé.

Quelle est la façon d’agir des régies régionales dans le processus de gouvernance?

Comment cette façon d’agir favorise-t-elle l’application des politiques?

Cadre analytique :

Afin de mieux comprendre le rôle des régies régionales dans les processus de gouvernance, nous nous sommes appuyé sur quatre construits conceptuels correspondant aux modèles d’action collective : politique, technocratique, démocratique et cognitif.

En plus des quatre modèles, nous avons analysé l’incidence de la gouvernance sur la mise en oeuvre des politiques de santé en utilisant le cadre analytique général de Mazmanian et Sabatier, qui cerne trois types de variables influençant l’application des politiques publiques : (1) les variables reliées à la complexité du problème, (2) les variables d’origine législative qui structurent la mise en oeuvre des politiques et (3) les variables d’origine non législative reliées au contexte.

Méthodes :

Nous avons effectué une étude de cas qualitative et longitudinale de la mise en oeuvre régionale du Programme de lutte contre le cancer au Québec.

Constatations :

Cette recherche souligne la valeur ajoutée d’une gouvernance clinico-administrative du changement, en vertu de laquelle les régies régionales – en synergie avec des cliniciens leaders – aident à orienter l’action collective. Une analyse des façons d’agir des régies régionales révèle l’utilité d’une combinaison des modèles d’actions technocratiques, démocratiques, politiques et cognitives.

In many developed nations, the legitimacy of the state’s role in public policy implementation is increasingly being questioned. That a recent issue of Public Administration was devoted to the topic illustrates the scope and relevance of these concerns (see Barrett 2004; Exworthy and Powell 2004; O’Toole 2004; Schofield 2004). Explanations of the problems afflicting policy implementation have long focused on the approach adopted – i.e., top-down (Sarbaugh-Thompson and Zald 1979) or bottom-up (Berman 1978; Hjern et al. 1978). Proponents of the top-down approach address control and communication among hierarchical levels. Supporters of the bottom-up approach, however, consider the political micro-processes at play among stakeholders that have different interests and, often, irreconcilable values. In their view, the implementation of public policy results from negotiation (Strauss 1978) that depends on the structure of the network of stakeholders, their interaction and the distribution of power among them.

Most recent research (e.g., O’Toole 2000; Meier et al. 2004) devoted to public policy analysis places greater emphasis on the question of governance, understood in the broadest sense as the organization of collective action (Prakash and Hart 1999). Governance is concerned more with strategic issues than with management. It centres on a continuous process of interaction and negotiation among stakeholders at multiple levels. To govern is to adopt common representations, structures, rules and performance indicators with a view to coordinating stakeholders so that power can be exercised in a pluralistic manner. Taking a governance perspective makes it possible to go beyond the top-down versus bottom-up debate because it accounts for both process and the distributed nature of collective action. Because governance emphasizes that a number of stakeholders who do not necessarily share the same interests can – and often do – participate in managing public affairs, the concept makes it possible to link various levels of analysis concerning the role of the community, civil society, private enterprise, local and regional government and the state (Daly 2003).

In this paper, we focus on governance and the added value of regionalization in the context of health policy implementation. In most Canadian provinces, regionalization – the establishment of an intermediate governing structure at the regional level that assumes functions previously fulfilled by a central or local government (Lewis and Kouri 2004) – has been aimed at reinforcing governance capacity. Ambitions have been high: redefining accountability rules, democratizing decision-making, enhancing responsiveness to public needs, increasing the fairness of resource distribution among regions, developing a more comprehensive approach to health problems, using resources more efficiently and improving continuity of care. Opinions on the effectiveness of regionalization are, however, divided (Church and Barker 1998; Davis 2004; Levine 2004; Sullivan et al. 2004). Even if some progress has been made (Gosselin 1984; Lewis and Kouri 2004; Denis et al. 2004), regionalization’s full potential has not been realized (Church and Barker 1998; Lamarche 1996; Lewis 1997; Hurley 2004; Lewis and Kouri 2004).

Our objective here is not to offer an opinion on the potential of regionalization but to generate a more thorough understanding of the role regionalization plays in health policy implementation. We carry this out by exploring two main questions:

What are regional boards’ patterns of action in the governance process?

How do these patterns favour policy implementation?

In order to answer these questions, we take the Programme de lutte contre le cancer (PLC) (Program to Combat Cancer) adopted by Quebec’s Ministry of Health and Social Services in 1998 (Ministère de la santé et services sociaux 1997) as a good illustration of regionalization’s potential to be an effective governance tool.

We begin our discussion by clarifying the form regionalization has taken in Quebec and the objectives and means PLC adopted. Next, we describe our analytical framework and methodology. We then present and analyze our findings based on an evaluation of PLC’s implementation in the Montérégie region (Roberge et al. 2004). Our paper ends with a general consideration of regionalization and the threats it faces.

Overview

Regionalization in Quebec

Beginning in the 1970s and extending through the end of the 1990s, Quebec was the first Canadian province to gradually regionalize its healthcare system (Turgeon et al. 2003). The province’s regional boards have three main responsibilities:

planning health services

organizing health services

allocating resources among healthcare institutions

On the last point, it should be noted that Quebec’s regional regulatory bodies do not control payments to physicians.

Quebec’s Program to Combat Cancer

Quebec’s Ministry of Health and Social Services adopted PLC in response to the province’s high rate of cancer and to address gaps in the organization of services affecting responsiveness to the needs of cancer patients and their families as well as the quality and efficiency of care. To enhance accessibility, continuity and service quality, a provincial task force developed a program that included reorganizing services and establishing integrated regional oncology networks. The reorganization comprised

creation of regional centres of excellence, whose role was to offer, in conjunction with other local institutions, specialized and ultra-specialized oncological services;

introduction of procedural and organizational measures to foster healthcare coordination, including the creation of multidisciplinary local, regional and supra-regional teams in oncology; the introduction to each team of a nurse case manager in oncology who would assess clients’ overall needs and coordinate services; the harmonization of professional practices; and the formalization of links between institutions.

Implementing these networks implied strengthening collaboration among professionals as well as various organizations such as hospitals, private medical clinics, community organizations and local community health centres (Centres locaux de service communautaires [CLSCs]), which are primary care facilities offering medical and psychosocial services.

The context in Montérégie

In 1999, the Montérégie health and social service region undertook this process change. Located south of Montreal, Montérégie is the second most populated region in Quebec. Its residents are highly mobile and use health services in neighbouring cities. At the time, oncological services in the region were provided by eight local hospitals, a regional university hospital that in the mid-1990s became a centre of excellence in oncology, 19 CLSCs and several private medical clinics.

In its 1999–2002 strategic plan, Montérégie’s regional board gave high priority to the fight against cancer. The regional hospital’s recruitment in 1999 of a leading oncologist (one of PLC’s designers and promoters) played a key role in this decision.

Analytical Framework and Methodology

Analytical framework

In order to answer our research questions, we needed first to clarify our understanding of governance and the role of regional boards in governance processes and the determinants of policy implementation success.

Governance models

For the purposes of our study, we understood governance to be based on an interactive, multi-centric view of collective action. This means, in particular, that our analysis of governance focused on the roles various stakeholders played in steering change. For instance, regional boards in Canada are often expected to influence physicians – particularly powerful members of the healthcare community – through levers such as resource allocation. Regionalization is also expected to redistribute power among health institutions by strengthening the role of community organizations, which have, historically, been less powerful than hospitals.

To enhance our understanding of the role of regional boards in governance processes, we relied on conceptual constructs that corresponded to models of collective action. These models constitute ideal types as defined by Weber (1992, cited in Encyclopedia Britannica 2006): a “common mental construct in the social sciences derived from observable reality although not conforming to it in detail because of deliberate simplification and exaggeration.” As a conceptual tool, an ideal type is useful for comprehending the reality of a given situation, relationship or organization.

Denis et al. (1998) and Contandriopoulos et al. (2004) identify three models of collective action. The technocratic model involves obedience to a central government, which sets policies, delegates and controls. Under this model, the legitimacy of Quebec’s regional boards derives from the Ministry of Health and Social Services. The political model corresponds to a political perspective on change. Accordingly, a regional board’s “legitimacy” derives from “the fact that significant actors and organizations perceive themselves as being part of the decision process” (Contandriopoulos et al. 2004: 632). Regional boards thus enjoy broad autonomy and adopt tactics, set agendas, define rules of negotiation to influence the redistribution of power and foster negotiation among stakeholders. Under the democratic model, which corresponds to an institutional perspective, a regional board’s legitimacy “comes from making plausible the claim that deliberative processes are not biased and that the governing body can implement policies according to the collective will” (Contandriopoulos et al. 2004: 633). The role of regional boards is therefore to contribute to the democratization of society by fostering public participation and limiting the risk of domination by influential interest groups. As Contandriopoulos (2004) has shown, public participation is a complex political phenomenon. Yet this should in no way be interpreted as a fatalistic statement implying that we should not care about institutional arrangements. Consequently, in this paper we maintain the democratic model as a separate analytical model.

While useful, these three models do not reveal the cognitive nature of the processes by which public policy is implemented. Increasingly, research in this area (Aggeri 1999; Hall 1993; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1993; Schofield 2004) supports placing greater emphasis on the role that knowledge plays in change processes (Touati et al. 2004, 2005). This emphasis gives rise to the cognitive model, which describes the role regional boards play in promoting learning. While the cognitive model is closely linked to the political model, by fostering exploratory learning regional boards are not necessarily aware of the strategic interests for which they are working. Even if knowledge production can be used to change the rules of the game and the distribution of power, comprehending this variable needs to take into account its relative freedom as a distinct phenomenon.

In the final analysis, we have adopted all four possible models of action in order to comprehend fully the role of regional boards in governance processes. As we noted earlier, these models are ideal types, which means that reality often corresponds to a complex combination of the four.

Policy implementation and its determinants

Alongside the four models, we analyzed the impact of governance on health policy implementation using Mazmanian and Sabatier’s (1983) general analytical framework, which identifies three types of variables that affect public policy implementation. The advantage of this framework is that it allows us to understand, without imposing a restrictive assumption, the variables activated by the regional authority to favour policy implementation. These variables are

those related to a problem’s complexity (e.g., technical difficulties, behavioural diversity, scope of change);

“statutory” variables that structure policy implementation (e.g., clarity and coherence of objectives, clarity of a theory of causality, allocation of initial resources, coordination among institutions, possibility of intervention by outsiders, decision-making rules available to stakeholders); and

“non-statutory” variables related to implementation context (e.g., socio-economic conditions, support from interest groups and stakeholders, stakeholders’ leadership).

Figure 1 illustrates our analytical framework. It reveals that the specific form of governance and its impact on health policy implementation are influenced by a particular context at two levels: the provincial (e.g., the organizing principles of the healthcare system) and the regional (e.g., availability of human and physical resources, nature of pre-existing relationships among stakeholders).

FIGURE 1.

Analytical framework: Relations between governance and health policy implementation

Methodology

Research strategy

In keeping with our analytical framework, our research strategy involved a qualitative, longitudinal case study (Patton 1990; Yin 1994) of PLC’s implementation at the regional level from the project’s inception in 1999 to fall 2003. This approach made it possible to examine the governance process from a dynamic, contextual viewpoint.

Data sources

Our analysis drew primarily on qualitative data derived from the following sources:

non-participant observation (beginning October 2001) at most administrative meetings (N=50) involving regional governance of change;

semi-structured interviews (N=65) with network promoters (e.g., clinicians and representatives from the regional board), professionals from multidisciplinary teams and hospital managers (e.g., nurse managers, heads of oncology outpatient clinics). We transcribed all interviews and coded them using Nudist 6.0 software;

documentary analysis, including all inter-organization agreements, task force reports and the steering committee’s financial reports.

We also cross-tabulated the various data sources to strengthen the study’s internal validity.

Data analysis

Our data analysis focused primarily on two strategies: a narrative strategy that highlighted the context in which PLC was implemented and a chronological breakdown strategy (Langley 1999) that enabled us to examine how previous actions affected the context in which subsequent actions took place. During the course of our study, we used intermediate written reports and oral presentations to create interactions between our research team and the local stakeholders involved in the policy implementation. This validation process revealed a convergence between our theory of action and stakeholders’ perceptions.

Findings

Descriptive

Was the policy implementation successful?

Considerable progress was made in implementing PLC during the period covered by our study (Roberge et al. 2004). Most of the respondents shared the philosophy and vision the program promoted. We also found that inter-professional trust and respect had developed within local teams in all the hospitals. Similarly, inter-organizational trust appeared to be strong.

From a clinical standpoint, multidisciplinary teams were implemented and met regularly in all the region’s hospitals, and the position of nurse case manager in oncology was created. Numerous measures to coordinate team members were introduced (e.g., patient profiles). Tools to aid clinical intervention, however, were adopted at a slower pace (e.g., quality standards and clinical protocols). In almost all instances, organizational efforts were made to enhance the management of oncological emergencies.

From an administrative standpoint, every hospital made an effort to enhance the stability of its oncology teams (e.g., by reducing staff rotations). In all instances, respondents said they had benefited from management’s administrative support to create clinical teams. The nature and intensity of such support varied, however, among the hospitals. Those differences appeared, in particular, in professionals’ participation rates in training and the presence or absence of coordinators (e.g., the replacement of nurse case managers during vacation periods).

What did the regional board do to support policy implementation?

By and large, progress resulted from effective governance. Initially, the regional board decided in early 1999 to mandate the main regional hospital to implement the integrated oncological service network in order to take advantage of its key oncologist’s expertise. In light of resistance from the other hospitals in the region, whose directors and physicians feared the loss of their clientele and their professional autonomy, the regional board decided to involve itself more extensively in the governance of change. The director of the regional board’s medical affairs department approached hospital medical directors with whom he had good relations in order to create a temporary committee responsible for PLC’s implementation. To encourage the hospitals to take part in the change process, this committee divided funding among the various organizations, based on a study of their needs, to cover pharmaceutical services. It also invited the haemato-oncologists to a meeting of the regional medical directors’ advisory board to explain the reorganization objectives. Although the status quo was maintained, it was decided to move ahead with the project.

To this end, a steering committee was created comprising representatives of the regional board and the region’s health organizations. During the period of our study, the steering committee played a decision-making role with regard to developing strategy related to the integrated oncological services network. It also managed the budget granted by the regional board to implement the program. At the same time, the regional board attempted to broaden participation in governance by adding an advisory committee to the steering committee. This advisory committee comprised representatives of healthcare organizations, various types of healthcare professionals, community organizations and users.

Because of physician resistance, the steering committee adopted an incremental, small-step approach to change (Touati et al. 2006). In phase 1, it sought to overcome stakeholder resistance. This endeavour led to a search for regional allies and a revision of the governance structure. During phase 2, the committee introduced case manager nurses, hoping these agents of change would gradually alter teams’ practices. Considerable effort was invested in training these nurses, who received extensive supervision from a regional expert. In phase 3, the committee consolidated change by gradually training the other members of the hospital teams and partner organizations. Psychosocial professionals were also added to the outpatient clinic teams. Finally, in phase 4 the committee sought to involve the physicians more extensively by establishing a regional haemato-oncologists’ committee, which was responsible for harmonizing and enhancing medical practices using evidence-based information. The steering committee also endeavoured to broaden the role of primary care physicians in managing cancer patients by promoting the idea that they could devote part of their practices to the treatment of acute-stage cancer patients. However, the regional board department responsible for organizing general medical services has, to date, not accepted this approach, arguing that it could hamper primary care.

During all four phases, the clinical leaders played a predominant role insofar as they often initiated the measures adopted and worked hard to ensure the measures’ success. By relying on their expertise and several tactics to exercise influence, they succeeded in altering practices (Touati et al. 2006). This experience highlights the importance of the clinical governance of change, and the role played by the regional board has been essential in several respects. As one clinical leader told us:

Working with the regional authority is innovative. We assume that regional boards and hospitals talk to each other. But, it is not the real life. We have proven that, in Montérégie, we are able to work together. The regional authority has been very helpful; probably without this partnership with the regional authority, things would have been different. We have seen what a regional authority can do for the network. Yes, I think that is innovative.

The regional board’s essential role in implementing PLC and steering change was illustrated in several ways and on numerous occasions:

The board’s initial intervention (i.e., revision of governance structures and recruitment of new stakeholders) was key to defusing the implementation crisis and overcoming resistance.

The board provided funding to implement PLC.

The board planned the care continuum by assessing the needs of Montérégie’s population with respect to services and organization.

Sustained participation by board representatives in various governance committees and working groups fostered discussions and helped to coordinate initiatives.

The board’s practical support (e.g., organizing committee teleconferencing) enabled necessary discussions.

Evaluations undertaken by the board, especially on the role of psychosocial professionals, encouraged stakeholders to question the relevance of certain choices pertaining to service organization.

The board guaranteed coherence of the overall organization of services (e.g., involvement of general practitioners in treating cancer patients).

Analytic

How can we understand the regional board’s models of action?

Our retrospective analysis of the regional board’s initiatives revealed the combined mobilization of the four models discussed earlier. Following a technocratic model, at the outset the regional board adopted measures designed to defuse the crisis by reviewing governance structures and emphasizing its ministry- mandated responsibilities. The democratic model surfaced during the implementation crisis. At that time, there was an attempt to include stakeholders who traditionally have wielded less power (e.g., community organizations and users) in the advisory committee. To date, this model of action has had relatively little impact, most likely because the crisis was resolved.

Use of the political model was, however, essential to PLC’s implementation. Evidence of this model arose in the deployment of the regional board’s economic power (i.e., funds drawn from its own budget) to influence negotiations among stakeholders. The political model was also manifested through the board’s contacts with allies in the region, alliances with clinical leaders, orientation of the decision-making agenda through governance structures and authority over service organization.

The regional board also adopted several measures that conform to the cognitive model. In order to encourage a collective learning process, it facilitated exchanges among stakeholders, implemented information systems (e.g., tumour registry), planned service organization using evidence-based information, assessed the new role of psychosocial professionals and involved an evaluation team.

How has governance supported policy implementation?

In order to deal with suboptimal conditions, the regional board gradually tackled the variables that affected policy implementation, whether associated with context, formal structuring or problem complexity. It is clear that an effort was initially made to intervene to influence context-related variables. For example, an attempt was made to gain the support of certain stakeholders, such as nurses. Nurses were allies of change in light of their increased prestige as case managers. Some hospital medical directors also rallied to the program. In fact, they trusted the regional board and were also more aware of PLC’s potential because of the precariousness of their institutions in terms of medical staff availability.

In light of such support, governance focused on structuring implementation. Change was initiated through the allocation of resources, PLC’s objectives were specified and clarified (e.g., the regional action plan and its dissemination, measures adopted to assess the effects of change) and efforts were made to promote stakeholder coordination at the regional and provincial levels. The participation of regional stakeholders in the deliberations of the provincial committee also ensured feedback on the provincial implementation strategy.

Reducing the scope of change also helped by limiting the complexity of implementation. For example, it was decided to avoid broaching at the outset the question of modifying service corridors. Indeed, stakeholders counted more on possible gains in the comprehensiveness and continuity (especially among team members) of care.

Success resulted from establishing synergy between clinical and administrative leadership. Stakeholder support, for instance, was made possible by the efforts of the regional board, which rallied to champion certain hospital medical directors and clinical leaders, who in turn banked on the nurse case managers. Similarly, stakeholder coordination was carried out by relying on administrative and clinical leaders.

Table 1 summarizes the phases involved in PLC’s implementation. For each phase, we have highlighted the governance process, emphasizing the regional board’s patterns of action (Denis et al. 1998) and the roles of other stakeholders. The final column explains, following Sabatier and Mazmanian (1983), how the governance process supported policy implementation.

TABLE 1.

Governance and its impact on PLC’s implementation

| PHASE | GOVERNANCE | VARIABLES MOBILIZED TO FOSTER PLC’S IMPLEMENTATION | |

|---|---|---|---|

| THE REGIONAL BOARD’S MODELS OF ACTION | STAKEHOLDERS’ ROLES | ||

| Phase 1: Overcame stakeholders’ resistance | Political model: Mobilized stakeholders with whom trusting relationships existed; influenced the decision-making agenda by participating in governance. Technocratic model: Relied on the regional board’s political legitimacy to broaden stakeholders’ participation. Democratic model: Involved stakeholders that traditionally exercised little power in governance. | Clinical leaders: Forged alliances with nurses. | Context: Sought allies. Implementation: Reviewed governance structures. |

| Phase 2: Introduced agents for change | Political model: Used financial resources to fund the role of case manager nurses and to orient the decision-making agenda. | Clinical leaders: Trained and supported nurses in fulfilling their role. | Complexity: Simplified change by initially confining the initiative to the introduction of the nurse case manager role. Implementation: Provided resources for change. |

| Phase 3: Consolidated change | Political model: Used financial resources to fund the expansion of clinical teams and to orient the decision-making agenda. Cognitive model: Targeted priorities in light of the assessed needs and validated them by means of evaluation projects related to the choices adopted. | Clinical leaders: Trained and supported the entire team. | Implementation: Clarified the pattern of action by designing and disseminating a regional action plan; validated the theory of action by evaluating the service organization model and the change process; coordinated stakeholders. |

| Phase 4: Involved physicians more extensively | Cognitive model: Supported exchanges among professionals and promoted the process using evidence-based information. Political model: Relied on the regional board’s authority to ensure the program’s implementation did not harm primary care services. | Clinical leaders: Led the regional medical committee. | Implementation: Clarified the pattern of action by fostering the emergence of consensus concerning medical practices; endeavoured to involve primary care physicians more extensively. |

Discussion and Conclusion

Our research underscores the added value of a clinico-administrative governance of change, whereby regional boards, in co-operation with clinical leaders, orient and direct collective action. Such a governance strategy can help to ensure the implementation of health policies and, as we have shown, can influence the determinants of policy implementation: complexity, implementation structure and context.

As the PLC case revealed, the specific form of governance and its impact on health policy implementation depend on pre-existing context (e.g., the availability of financial resources, relationships among stakeholders, the presence of leaders). More precisely, our analysis of the regional board’s actions reveals the utility of a combined adoption of technocratic, democratic, political and cognitive models.

A question that naturally arises is, however, whether another stakeholder could have assumed the role played by Montérégie’s regional board. Our study strongly suggests that fulfillment of this role required a sufficient knowledge of local context, which was particularly useful during negotiations. We believe that a provincial body would have had more difficulty gathering this information and that a local stakeholder in possession of levers similar to those described above (e.g., financial incentives, alliances) was best positioned to carry out such a role.

Analyzing the role of regional boards illuminates the ways in which governance structures can support complex changes. That said, we believe that if what is at stake is no longer to implement a health policy but to coordinate such policies to produce optimal efficiency, population-based regional governance is probably more effective than other models (e.g., governance centred on the organization of services by diseases). Regionalization’s added value resides precisely in the coordination of disease-based networks with primary care services. Such coordination is essential to the continuity and comprehensiveness of care.

The Montérégie experience indeed shows that making a regional board responsible for ensuring the integration of services by disease does not lead to the disintegration of primary care (Leutz 1999). As some experts have noted (Lenay et al. 2002), industrialized jurisdictions are witnessing a major change in the purpose of governance, which henceforth will focus on the care of people suffering from multiple diseases. To this end, the role played by stakeholders (e.g., regional boards) that have a systemic perspective and are accountable for the health of entire populations is all the more relevant.

Beyond the lessons to be drawn from implementing PLC in Montérégie, insights concerning regional boards’ models of action can be gained. First, it is important to emphasize the value of the cognitive model. Indeed, this model could provide a counterbalance to the political model, which is often associated with regionalism (a tendency by regional boards to demand resources for their regions while claiming that doing so enhances access to healthcare). It seems not unreasonable to believe that the cognitive model could limit the perverse effects of a model of action that induces strategic actors to attempt to bolster their power by, for example, monopolizing resources. Deployment of the cognitive model would make it possible to validate choices with respect to service organization (e.g., by referring to their effect on healthcare accessibility).

Unlike certain analysts (e.g., Church and Barker 1998), we do not believe that regionalization must go hand in hand with the containment of service utilization to avoid transaction costs stemming from inter-regional transfers. It could, in fact, be possible to serve the population of one region by means of another region’s resources if such a transfer allowed for gains in the overall efficiency of care, notwithstanding transaction costs. Such a scenario would be especially possible in regions surrounding large cities, where there are fewer problems in access to care.

It is important at this point, however, to insert a note of caution. While the utility of the cognitive model is obvious, its implementation is nonetheless far from straightforward. Evaluating service organization is complex (Pineault et al. 1993), and regional boards do not necessarily have the staff necessary to oversee the process. This dilemma certainly warrants consideration in terms of central authorities’ responsibility to provide adequate support for regions. No doubt, the expertise of public health departments would prove highly useful in this learning process.

Acknowledgment

This paper is based on the results of an evaluation study financed by the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation.

Contributor Information

Nassera Touati, École Nationale d’Administration Publique, Montreal, QC.

Danièle Roberge, Centre de recherche Hôpital Charles Lemoyne, Greenfield Park, QC.

Jean-Louis Denis, Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC.

Raynald Pineault, Direction de santé Publique de Montréal, Montreal, QC.

Linda Cazale, Centre de recherche Hôpital Charles Lemoyne, Greenfield Park, QC.

Dominique Tremblay, Université de Montréal, Centre de recherche Hôpital Charles Lemoyne, Greenfield Park, QC.

References

- Aggeri F. Environmental Policies and Innovation. A Knowledge-Based Perspective on Cooperative Approaches. Research Policy. 1999;28:699–717. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett S.M. Implementation Studies: Time for a Revival? Personal Reflections on 20 Years of Implementation Studies. Public Administration. 2004;82(2):249–62. [Google Scholar]

- Berman P. The Study of Macro and Micro Implementation. Public Policy. 1978;27:157–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church J., Barker P. Regionalization of Health Services in Canada: A Critical Perspective. International Journal of Health Services. 1998;283:467–86. doi: 10.2190/UFPT-7XPW-794C-VJ52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contandriopoulos D. A Sociological Perspective of Public Participation in Health Care. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;58(2):321–30. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contandriopoulos D., Denis J.-L., Langley A., Valette A. Governance Structures and Political Processes in the Public System: Lessons from Quebec. Public Administration. 2004;82(3):627–54. [Google Scholar]

- Daly M. Governance and Social Policy. Journal of Social Policy. 2003;32(1):113–28. [Google Scholar]

- Davis J. Let Regionalization Continue to Evolve. Healthcare Papers. 2004;5(1):50–54. doi: 10.12927/hcpap..16839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis J.-L., Contandriopoulos D., Langley A., Valette A. Les Modèles théoriques et empiriques de régionalisation du système socio-sanitaire. Montreal: University of Montreal; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Denis J.-L., Contandriopoulos D., Beaulieu M.-D. Regionalization in Canada: A Promising Heritage to Build On. Healthcare Papers. 2004;5(1):40–45. doi: 10.12927/hcpap..16837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encyclopedia Britannica. Ideal Type. 2006 Retrieved December 28, 2006. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9042017/ideal-type .

- Exworthy M., Powell M. Big Windows and Little Windows: Implementation in the Congested State. Public Administration. 2004;82(2):263–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin R. Decentralization ∕ Regionalization in Health Care: The Quebec Experience. Health Care Management Review. 1984;9(1):7–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P. Policy Paradigm, Social Learning and the State. Comparative Politics. 1993;25(3):275–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hjern B., Hanf K., Porter D. Local Networks of Manpower Training in the Federal Republics of Germany and Sweden. In: Hanf K., Scharpf F.W., editors. Interorganizational Policy Making. London: Sage; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley J. Regionalization and the Allocation of Healthcare Resources to Meet Population Health Needs. Healthcare Papers. 2004;5(1):34–39. doi: 10.12927/hcpap..16836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche P. Décentralisation et démocratisation: des enjeux déterminants de la transformation des systèmes socio-sanitaires. Academy of Management Review. 1996;24(4):691–710. Cited in A. Langley, “Strategies for Theorizing from Process Data.”. [Google Scholar]

- Langley A. Strategies for Theorizing from Process Data. Academy of Management Review. 1999;24(4):691–710. [Google Scholar]

- Lenay O., Engel F., Moisdon J.-C. La Dynamique des politiques sanitaires: l’emergence d’un nouvel objet de gouvernement trajectoires de patients. Le Cas de la prise en charge en dialyse et en cardiologie. Paper presented at the Fourth European Conference on Health Economics, Paris. 2002. Jul,

- Leutz W.N. Five Laws for Integrating Medical and Social Services from the United States and the United Kingdom. Milbank Quarterly. 1999;77(1):77–110. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine D. An Opportunity for Improving Management. Healthcare Papers. 2004;5(1):46–49. doi: 10.12927/hcpap..16838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S. Occasional Paper 2. Saskatoon: HEALNet Regional Health Planning; 1997. Regionalization and Devolution: Transforming Health, Reshaping Politics. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S., Kouri D. Regionalization: Making Sense of the Canadian Experience. Healthcare Papers. 2004;5(1):12–33. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2004.16847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian D., Sabatier P.A. Implementation and Public Policy. London: Arnold Meltsner and Mark Moore; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Meier K.J., O’Toole L.J., Jr., Crotly S.N. Multilevel Governance and Organizational Performance: Investigating the Political–Bureaucratic Labyrinth. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2004;23(1):31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la santé and des services sociaux. Programme québécois de lutte contre le cancer. Pour lutter efficacement contre le cancer, formons équipe. Quebec: Government of Quebec; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole L., Jr. Research on Policy Implementation: Assessment and Prospects. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2000;10(2):263–88. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole L., Jr. The Theory–Practice Issue in Policy Implementation Research. Public Administration. 2004;82(2):309–30. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Pineault R., Lamarche P., Champagne F., Contandriopoulos A.-P., Denis J.-L. The Reform of the Quebec Health Care System: Potential for Innovation? Journal of Public Health Policy. 1993 Spring;:198–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash A., Hart J.H. Globalization and Governance: An Introduction. In: Prakash A., Hart J.H., editors. Globalization and Governance. London: Routledge; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Roberge D., Denis J.-L., Cazale L., Comtois E., Pineault R., Touati N., Tremblay D. Évaluation du réseau intégré de soins and de services en oncologie: l’expérience de la Montérégie. Final Report. Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier P., Jenkins-Smith H. Policy Change and Learning. An Advocacy Coalition Framework. Boulder, CO: Westview; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sarbaugh-Thompson M., Zald M.N. Child Labor Laws: A Historical Case of Public Policy Implementation. Administration and Society. 1979;27(1):25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield J. A Model of Learned Implementation. Public Administration. 2004;82(2):249–62. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. Negotiations: Varieties, Contexts, Processes and Social Order. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan T., Debrow M.L., Thompson A. Reconstructing Cancer Services in Ontario. Healthcare Papers. 2004;5(1):69–80. doi: 10.12927/hcpap..16843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touati N., Contandriopoulos A.-P., Denis J.-L., Rodriguez R., Sicotte C. The Integration of Health Care Services as a Solution to the Problem of Access to Care in Rural Areas: What Leverage Mechanisms Do Regulatory Agencies Have in a Public System? A Quebec Case Study. Health Care Management Review. 2004;29(3):249–57. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touati N., Denis J.-L., Contandriopoulos A.-P., Beland F. Introduire le changement dans les systèmes de soins: comment tirer profit de l’expérimentation sociale. Sciences Sociales et Santé. 2005;23(2):75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Touati N., Roberge D., Denis J.-L., Cazale L., Pineault R., Tremblay D. Clinical Leaders at the Forefront of Change in Health Care Systems: Advantages and Issues. Lessons Learned from the Evaluation of the Implementation of an Integrated Oncological Services Network. 2006. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Turgeon J., Anctil H., Gauthier J. L’Evolution du ministère and du réseau: continuité ou rupture? In: Lemieux V., Bergeron P., Begin C., Bélanger G., editors. Le Système de santé au Québec: organisations, acteurs et enjeux. Quebec: Laval University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yin R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods (2nd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]