Abstract

This paper reports on a research collective on primary healthcare (PHC) conducted in Quebec in 2004. Thirty ongoing or recently completed studies were synthesized through a process involving a high degree of exchange among researchers who conducted the original studies, investigators and decision-makers. The viewpoints expressed by decision-makers who participated in the process were analyzed in terms of convergence with and divergence from the researchers’ viewpoints. In four cases, there was convergence between the decision-makers’ and the researchers’ viewpoints, thus increasing the validity of the collective’s findings. The main divergence between the two groups’ viewpoints concerns the strategy adopted in Quebec to create local health and social services networks. Such divergence reflects the distinction made by Klein between scientific evidence and organizational and political evidence.

Our study results illustrate that decision-makers’ viewpoints can play an important interpretive and complementary role in producing research syntheses. Although integrating decision-makers’ viewpoints into syntheses has been regarded as a strategy for improving the use of research findings, our analysis shows that decision-makers’ view-points do not necessarily have to be integrated into syntheses but can, instead, be examined for convergence with or divergence from researchers’ viewpoints. This deliberative process can enrich discussions and lead to enlightened decision- and policy making.

Abstract

Cet article rapporte l’expérience d’un collectif de recherche sur les services de santé de première ligne menée au Québec en 2004. Trente études en cours ou récemment complétées ont été synthétisées au moyen d’un processus incluant un niveau élevé d’échange entre des chercheurs qui ont effectué les études initiales, des investigateurs et des décideurs. Les points de vue exprimés par les décideurs qui ont pris part au pro-cessus ont été analysés en vue de déterminer s’ils convergeaient avec ceux des chercheurs ou s’ils en divergeaient. Dans quatre cas, il y avait convergence entre les opinions des décideurs et celles des chercheurs, ce qui a rehaussé la validité des constatations du collectif. La principale divergence entre les points de vue des deux groupes avait trait à la stratégie adoptée au Québec pour créer des réseaux locaux de santé et de services sociaux. Une telle divergence reflète la distinction que fait Klein entre les preuves scientifiques et les preuves organisationnelles et politiques.

Les résultats de notre étude illustrent que les points de vue des décideurs peuvent jouer un important rôle interprétatif et complémentaire dans la production des synthèses de recherche. Bien que l’intégration des points de vue des décideurs aux synthèses ait été considérée comme une stratégie pour améliorer l’utilisation des résultats de recherche, notre analyse montre que ces points de vue n’ont pas nécessairement à être intégrés aux synthèses mais qu’ils peuvent plutôt être examinés en vue de déterminer s’ils convergent avec ceux des chercheurs ou s’ils en divergent. Ce processus de délibération peut enrichir les discussions et mener à un processus décisionnel et à une élaboration de politiques plus éclairés.

“Getting too close to decision-makers may jeopardize scientific credibility; remaining distant may undermine use.”

– Michael Quinn Patton

Interaction and exchange between researchers and decision-makers have been advocated as a promising strategy to increase the prospect for research use in management and policy making (Huberman 1994; Champagne et al. 2004; Lavis et al. 2002). While integrating decision-makers’ viewpoints into knowledge syntheses has been identified as a specific direction to ensure research use by decision-makers, attempts to have both researchers and decision-makers co-produce knowledge syntheses have been limited (Lomas et al. 2005; Black 2006; Lamarche et al. 2003; Lavis 2004; Walshe and Randall 2001). As Sheldon (2005) observes: “It is easy to talk about how important it is to promote communication between policy-makers and researchers and involve decision-makers in the production of reviews. It is less clear how this could be done in any meaningful way other than by including them in an advisory or reference group.” It is even less clear how decision-makers’ viewpoints can be taken into account in syntheses (Black 2001, 2006; MacLean 2006; Sheldon 2005; Pawson et al. 2005). One explanation of the difficulty of implementing a deliberative model of knowledge exchange between these two communities is the fact that systematic reviews generally rest upon published articles (Beyer 1997). Thus, the lack of timeliness of these research results reduces considerably their usefulness for decision-makers (Denis et al. 2004; Lavis et al. 2005; Innvaer et al. 2002; Walshe and Randall 2001).

The research collective, defined as “a process of dynamic exchange between a group of researchers and a lead team of investigators, resulting in the research synthesis of a limited number of projects on a given subject” (Pineault et al. 2006), addresses limitations inherent to systematic reviews. It creates conditions favourable to taking into account decision-makers’ viewpoints in the synthesis resulting from the collective (Black 2006; MacLean 2006). First, it involves decision-makers and researchers in a participative process for producing syntheses; second, the timely nature of the process stems from the fact that the research upon which it rests is either ongoing or recently completed (Pineault et al. 2005, 2006).

The objective of this paper is to present the process by which decision-makers participated in a research collective in primary healthcare (PHC) conducted in Quebec in 2004. It will also explore the extent to which decision-makers’ viewpoints can be taken into account through an analysis of their convergence with and divergence from the findings reported by the researchers on the same issues.

Background: PHC in Quebec

PHC has gone through major changes in the last few years in Quebec. In response to fragmented care and lack of coordination between PHC and specialized care, the Ministry of Health and Social Services created 95 health and social services centres (CSSSs) by merging local community health centres (CLSCs), residential and long-term care centres (CHSLDs) and, in most cases (75), acute care hospitals (Gouvernement du Québec 2006). CSSSs are responsible not only for providing services to the population of its territory, namely through its CLSCs, but also for ensuring that private clinics that provide nearly 90% of all PHC services under a fee-for-services mode of remuneration are also involved as partners in this endeavour. To achieve this objective, CSSSs are leading the process of establishing family medicine groups (GMFs) and network clinics (CRs) throughout the province. By January 2006, there were 105 accredited GMFs spread over close to 190 clinical sites. The creation of GMFs and CRs was meant to encourage clinics to get together and collaborate with CLSCs and hospitals in an effort to provide better integrated care with no change for the moment in the fee-for-services mode of remuneration of physicians (Gouvernement du Québec 2006). The intention of the Ministry is that all private clinics will eventually be linked to GMFs and CRs and, consequently, to CSSSs.

The Process of Involving Decision-Makers in the Collective

The research collective involved the active and direct participation of the researchers responsible for 30 ongoing or recently completed research projects with a team of investigators who led this participative process and did the synthesis. The process of exchange between the researchers listed in Appendix 1 and the investigators who co-authored this paper has already been presented (Pineault et al. 2006).

Although the research collective was clearly investigator driven, it involved a high degree of participation by decision-makers (Black 2006). The latter’s contribution was sought on different occasions: in June 2004 at a seminar meeting where researchers presented their work, and in February 2005 at a knowledge-exchange meeting where the collective’s report was released. Throughout the course of the collective, and more specifically on these two occasions, five decision-makers representing the Quebec Ministry, regional agencies and the public health sector were given documents beforehand and invited to comment. The panel also included a senior policy and management consultant.

At the two meetings, comments from the audience were gathered, especially at the February 2005 meeting, which was attended by more than 100 participants, about 50 of whom were policy makers. In addition, after the release of the report, the investigators did five presentations of the collective to decision-makers responsible for the implementation of the new local health and social services networks at the Ministry and at two regional agencies. Whereas the contribution of researchers remains extremely important and cannot be compared to that of decision-makers, in the context of interaction between decision-makers and researchers, the decision-makers’ participation was both important and significant. It played an interpretive role in that decision-makers’ reactions and comments to the material presented by the researchers at the June 2004 meeting considerably helped the investigators in elaborating an analytical framework and in analyzing and interpreting study findings.

The Viewpoints Expressed by Decision-Makers

The contributions of decision-makers also complemented the viewpoints expressed by the researchers, particularly during the February 2005 meeting and the five later meetings at which the collective was presented. The summary findings of the collective are presented in Table 1 in the form of key messages to decision-makers. Five points emerged from the June 2004 discussions and were integrated into the report in a separate section. A sixth point, raised at the knowledge-exchange meeting following the release of the report, opened up a process of exchange between researchers and decision-makers, but these discussions were not included in the final report.

TABLE 1.

Key messages to decision-makers

|

The points made by decision-makers in reaction to the findings of the collective presented by the researchers were the following:

There should be a balance between accessibility and continuity; solutions that seek to solve problems of accessibility alone are bound to fail.

The lack of participation and integration of physicians is a major obstacle to successful implementation of projects, and this is linked with their lack of institutional integration, modes of remuneration and lack of professional incentives.

Should disease or case management be a model for organizing healthcare services? The main conclusion of discussions on this question is the need for better articulation between the two.

PHC services, as currently organized in Quebec, are not adapted to complex problems; they are still suited for treating acute rather than chronic diseases, which require long-term involvement and responsibility.

There are striking differences between urban and rural areas; general practitioners’ multiple affiliations in rural areas and their presence in hospitals ensure a degree of continuity not found in urban regions, where practice tends to evolve more in silos.

Legislative measures and structural changes create favourable conditions for introducing changes in professional and clinical practices; this point was raised by decision-makers in support of legislation that forced CLSCs, acute care and long-term care hospitals to merge, and reduced the number of labour union accreditations.

These six points do not cover all the conclusions that emerged from the synthesis of the 30 studies, but only the viewpoints expressed by the decision-makers. Whether the questions that were not raised about some of the conclusions reached in the research synthesis implicitly reflect agreement of the decision-makers is highly plausible but was not formally assessed. Rather, our analysis focused on the viewpoints expressed by the decision-makers and their divergence or convergence with the corresponding conclusions in the collective’s report.

Convergence and Divergence of Decision-Makers’ Viewpoints with Those of Researchers

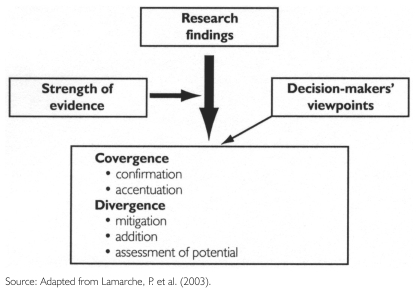

To examine the degree of convergence or divergence of decision-makers’ viewpoints with those of the researchers, we used an algorithm derived from the one we elaborated in a previous synthesis (Lamarche et al. 2003). It shows the different effects that can result from triangulation of the viewpoints (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Algorithm for the integration of researchers’ findings and decision-makers’ viewpoints

Convergence may either confirm the results reported in the research synthesis or accentuate them when they have not been firmly established. Divergence in viewpoints can mitigate the results reported in the collective when strong evidence is lacking or when nuances are needed in their interpretation. Divergence may also add to the results when decision-makers’ viewpoints address questions that have not been considered sufficiently in the collective. Finally, divergence may reflect decision-makers’ assessment of the potential of interventions that have not yet been evaluated but seem to be promising.

The six viewpoints expressed by the decision-makers are listed in Table 2, along with their corresponding effects on the findings reported in the collective. There is convergence between decision-makers and researchers on four of the six viewpoints. In the cases of integration of physicians and PHC not being adapted to complex chronic conditions, there is even an effect of accentuation, since the decision-makers’ viewpoint strengthens evidence not firmly established otherwise. Areas of divergence are sources of concern and require more detailed discussion.

TABLE 2.

Points of convergence and divergence between researchers and decision-makers

| Viewpoints expressed by decision-makers | Convergence / divergence with researchers’ findings |

|---|---|

| Balance between accessibility and continuity | Convergence (confirmation effect) |

| Urban / rural differences | Convergence (confirmation effect) |

| Integration of physicians | Convergence (accentuation effect) |

| PHC not adapted to complex problems | Convergence (accentuation effect) |

| Disease or case management | Divergence (addition effect) |

| Legislative and structural measures as facilitators for changing professional practices | Divergence (mitigation and assessment of potential effects) |

Model for PHC

The first source of divergence concerns the model that should be adopted for PHC. This divergence was rather surprising, as some decision-makers supported the disease management model of vertical integration rather than the case management model of horizontal integration. The findings of the collective added to evidence found in the literature that case management can better deal with a whole person than disease management. The disease management model handles with difficulty the problem of co-morbidities that are present in the majority of individuals with chronic diseases (Grumbach 2003). The argument put forward by the decision-makers in favour of disease management was partly based on the fact that disease management could be established more easily and rapidly by building on a more solid institutional and organizational foundation. Disease management will thus more readily solve the problem of vertical integration, viewed as a major problem in our system, than case management and population-based PHC models. It was also argued that in urban areas where there are plenty of specialized resources, the disease management model could be better adapted, whereas case management would be better suited to rural regions. However, there was no scientific evidence to support this view in the research synthesis.

No clear conclusion emerged from the discussions, but it was apparent that there is a need to articulate and coordinate the two models so as to reach systemic integration and facilitate patient access to a diversity of services at different levels in the healthcare system. The discussion brought additional elements to the researchers’ findings because management of diseases other than mental illnesses was not fully examined in the collective.

Legislation

The other area of divergence between decision-makers’ and researchers’ viewpoints was the contention that recent legislative measures the government has taken to create local health and social services by merging CLSCs, short-term and long-term hospitals will facilitate changes in clinical practice and induce the development of inter-professional and inter-organizational collaboration. The synthesis challenges this view. Here are two illustrative statements contained in the report:

The experience of implementing a local service network similar to those that are about to be established in Quebec shows that it is only when progress has been made in the realm of clinical integration that professionals and managers have been convinced of the importance of grouping institutions.

(Pineault et al. 2005: 12)

Integration factors are first and foremost clinical and human in nature; consequently, administrative mergers based on structures often hinder the development of networks.

(Pineault et al. 2005: 14)

In brief, the point made in the collective’s report is that clinical integration must precede administrative integration and not the opposite, and that emphasis should be placed on clinical practices rather than structures.

However, barriers to changing professional practices were identified, namely strong institutional and organizational allegiances. By merging organizations, the Ministry of Health expects healthcare organizations to better coordinate and integrate their practices rather than remain isolated and independent entities. Moreover, the legislative process is accompanied by strong ministerial support for the establishment of local networks. This support was also viewed in the collective as a necessary condition for their successful implementation. Several factors identified in the collective as facilitators for implementing integrated networks are found in the strategies applied by the Ministry, namely flexibility and adaptation to local conditions, balance between continuity and accessibility and better collaboration between PHC and other levels of care (Paquet 2005).

All things considered, it seems fair to conclude that reasons for divergence between researchers and decision-makers mitigate the conclusions drawn in the collective and indicate a potential effect, as assessed by decision-makers, of the legislative process on the successful implementation of the policy designed to create local health and social services networks in Quebec.

Discussion

Direct involvement of decision-makers in producing the synthesis was certainly an effective way to formalize personal contact between researchers and decision-makers, and encouraged the latter to use the results. One recent review on the use of evidence by decision-makers has shown that two-way personal communication with researchers was the most important condition for decision-makers’ utilization of research evidence (Innvaer 2002). A panel of five decision-makers was directly involved in the collective; after release of the report, the panel created opportunities to discuss and exchange viewpoints with a number of decision-makers. In this sense, the participation of decision-makers played both an interpretive and a complementary role in the collective.

Of course, it remains to be seen whether such an exchange will promote the enlightened use of research to better understand the complexity of issues, help establish goals and orientations and promote the instrumental or even the tactical use of research (Lavis et al. 2002, 2004; Innvaer 2002).

Although some authors have suggested that decision-makers’ viewpoints should be fully integrated into the conclusions reached in a synthesis, this goal could be difficult to achieve and perhaps hazardous (Lavis et al. 2005). Indeed, the question arises as to the weight that should be attributed to researchers’ and decision-makers’ viewpoints, respectively. Hence, it seemed preferable to propose an algorithm that helped examine convergence and divergence of viewpoints rather than forcibly integrate them with researchers’ findings. In looking at divergence and convergence of researchers’ and decision-makers’ viewpoints, the six points identified were only those raised by decision-makers. As mentioned earlier, points not raised by them but pinpointed in the collective were not considered in the analysis. It remains uncertain whether these points would correspond to areas of convergence or divergence. This issue should be addressed in future collectives.

Points of divergence deserve special attention, particularly the one raised by decision-makers concerning the structuring effect of merging on the establishment of local networks. In accordance with the deliberative model of knowledge utilization, we contend that it is more important to explain the source of divergence than to arrive at a final judgment that crystallizes a fixed point between the two positions (Denis et al. 2004).

The distinction Klein (2004) has made among three types of evidence sheds light on the integration of various perspectives in evidence gathering and on potential sources of divergence. He identifies three types of evidence: scientific, organizational and political. Scientific evidence is produced according to recognized standards of methodology; organizational evidence refers to feasibility and is concerned with factors such as financial constraints, managerial expertise and human resource requirements; political evidence refers to acceptability and is concerned with factors such as public opinion, media reactions and positions held by pressure groups. Within this framework, research evidence constitutes a necessary but not sufficient condition for organizational and political evidence to emerge.

Assuming that researchers’, managers’ and policy makers’ viewpoints reflect scientific, organizational and political evidence, respectively, one can hypothesize that the most successful managerial or policy decisions will likely result from an alignment of the three types of evidence (Black 2001). This situation would likely result also in more context-sensitive evidence (Tranfield et al. 2003; Lavis et al. 2005). Of course, the case that most concerns researchers is when scientific evidence yields a positive assessment of what works, and yet this intervention is never implemented because of lack of organizational and/or political evidence. Klein’s framework also suggests that targeted audiences for disseminating scientific evidence need not be restricted to decision-makers but could be more diversified and broadened to determinants of organizational and particularly of political evidence, namely media, pressure groups and the larger public.

Concerning the point made by decision-makers regarding the structuring effect of merging, neither the collective nor the literature supports this view (Lamarche et al. 2002; CHSRF 2000). On the other hand, strong and clear political support was expressed in legislation passed to create local networks and merge healthcare organizations as well as to ease human resource management by reducing the number of labour union accreditations. If we consider policy makers’ and managers’ engagement in the process as a reflection of political and organizational evidence, respectively, this case is a clear illustration of non-alignment between scientific evidence on one side and organizational and political evidence on the other. Further evaluation of the implementation of local networks in Quebec will reveal the extent to which political and organizational evidence, in the absence of scientific evidence, can predict the success of such an enterprise. Of course, we must keep in mind that scientific evidence is produced in a particular context. In this case, it is always possible that some contextual factors captured in organizational and political evidence and not in scientific evidence might exert a determining effect on the successful implementation of local networks. It could be argued that the collective’s findings and messages came late, since the decision to implement local networks had already been made and changes were underway. This fait accompli explains to a great extent the position held by the decision-makers on this issue. On the other hand, there is evidence that some of the measures recommended in the collective for successfully implementing changes in PHC have already been taken by the Ministry and regional agencies to implement the local networks (Paquet 2005).

These considerations call for a final remark regarding evidence. It is clear from the process involved in the collective and the cautious interpretation of its findings that the notion of evidence remains relative. This has been well expressed by Dobrow et al. (2004), who position “ideal evidence health policy” at a midpoint on an axis between evidence-based medicine and traditional political decision-making. There exists a strain between these two poles of evidence – from the breadth of contextual political elements to the depth of scientific evidence – and tradeoffs between the two are necessary for useful applications to decision-making. The question is whether the decision-maker should be given all the information and left with the task of integrating it into decision-making, or whether researchers can help and support decision-makers in this process.

Conclusion

The research collective is a form of knowledge synthesis that is interesting and useful in many respects, mainly because it meets several conditions that have been found to determine the prospect of research use by decision-makers (Lavis et al. 2005; Innvaer 2002). One of these conditions is the opportunity of exchange between researchers and decision-makers created throughout the collective that resulted in the research synthesis.

The collective opened the door for decision-makers to participate in the process. It provided opportunities to generate formal exchanges between researchers and decision-makers and to discuss their respective positions on issues raised during the exchange sessions. Instead of trying to force consensus on all the issues raised, respective viewpoints were examined through the use of an algorithm that helped identify and analyze the reasons for convergence and, particularly, divergence of viewpoints.

By creating a forum for exchange and discussion on the viewpoints expressed by these two communities, the collective has moved far beyond what is generally offered by systematic reviews. Such exchanges between researchers and decision-makers are more in line with a deliberative model of knowledge utilization and are more likely to lead to enlightened rather than only strategic use of knowledge (Denis et al. 2004; Lavis et al. 2004; Lomas et al. 2005). Recognizing that scientific evidence does not automatically result in organizational and political evidence and that an alignment of the three types of evidence will likely yield more progressive decision-making, the collective constitutes a promising tool for moving forward in this direction.

Acknowledgments

This study received financial support from the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (FCRSS) and the Réseau de recherche en santé des populations du Québec (FRSQ). Some of the institutions to which we are affiliated also provided substantial support. We also acknowledge the participation of L. Aucoin, M. Benigeri, P. Bergeron, D. Roy and L. Trahan as members of the decision-makers’ panel and J.L. Denis and L. Lamothe as moderators in the final discussion session. We extend our gratitude to L. Lapierre of the FCRSS for her unfailing support and to S. Gauthier and I. Rioux for their editorial assistance.

Contributor Information

Raynald Pineault, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Université de Montréal; Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire en santé, Montreal, QC.

Pierre Tousignant, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, McGill University, Montreal, QC.

Danièle Roberge, Centre de recherche Hôpital Charles-LeMoyne, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC.

Paul Lamarche, Université de Montréal, Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire en santé, Montreal, QC.

Daniel Reinharz, Département de médecine sociale et préventive, Université Laval, Quebec, QC.

Danielle Larouche, Université de Montréal, Centre de recherche Hôpital Charles-LeMoyne, Montreal, QC.

Ginette Beaulne, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Montreal, QC.

Dominique Lesage, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Quebec, QC.

References

- Beyer J.M. Research Utilization Bridging a Cultural Gap between Communities. Journal of Management Inquiry. 1997;6(1):17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Black C. The Research Collective: A Model for Developing Timely Contextually Relevant and Dynamic Approaches to Research Synthesis? Healthcare Policy. 2006;1(4):76–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black N. Evidence-Based Policy: Proceed with Care. British Medical Journal. 2001;323(4):275–78. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF) The Merger Decade. What Have We Learned from Canadian Healthcare Mergers in the 1990s? Report on the Conference on Healthcare Mergers in Canada. Ottawa: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Champagne F., Lemieux-Charles L., McGuire W. Introduction: Towards Broader Understanding of the Use of Knowledge and Evidence in Healthcare. In: Lemieux-Charles L., Champagne F., editors. Using Knowledge and Evidence in Healthcare. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Denis J.L., Lehoux P., Champagne F. A Knowledge Utilization Perspective on Fine-Tuning Dissemination and Contextualizing Knowledge. In: Lemieux-Charles L., Champagne F., editors. Using Knowledge and Evidence in Healthcare. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrow M.J., Goel V., Upshur R.E. Evidence-Based Health Policy: Context and Utilisation. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;58(1):207–17. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouvernement du Québec. Guaranteeing Access: Meeting the Challenges of Equity, Efficiency and Quality. 2006 Retrieved April 11, 2007. http://www.acaho.org/docs/pdf_2006_guaranteeing_access_quebec_government_reply.pdf .

- Grumbach K. Chronic Illness, Comorbidities, and the Need for Medical Generalism. Annals of Family Medicine. 2003;1(1):4–7. doi: 10.1370/afm.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberman M. Research Utilization – The State of the Art. International Journal of Knowledge Transfer and Utilization. 1994;7:13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Innvaer S., Vist G., Tremmaid M., Oxman A. Health Policy-Makers’ Perceptions of Their Use of Evidence: A Systematic Review. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2002;7(4):239–44. doi: 10.1258/135581902320432778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R. Evidence and Policy: Interpreting the Delphi Oracle. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2003;96:429–31. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.9.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche P., Beaulieu M.D., Pineault R., Contandriopoulos A.P., Denis J.L., Haggerty J. Choices for Change: The Path for Restructuring Primary Healthcare Services in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche P., Lamothe L., Bégin C., Léger M., Vallière-Joly M. L’Intégration des services: enjeux structurels et organisationnels ou humains et cliniques. Ruptures. 2002;8(2):71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lavis J. A Political Science Perspective on Evidence-Based Decision Making. In: Lemieux-Charles L., Champagne F., editors. Using Knowledge and Evidence in Healthcare. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lavis J., Davies H., Oxman A., Denis J.L., Golden-Biddle K., Furlie E. Towards Systematic Reviews That Inform Healthcare Management and Policymaking. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2005;10(Suppl. 1):35–48. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis J.N., Ross S.T., Hurley J., et al. Examining the Role of Health Services Research in Public Policy Making. Milbank Quarterly. 2002;80(1):125–54. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J., Culyer T., McCutcheon C., McAulay L., Law S. Conceptualizing and Combining Evidence for Health System Guidance. Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- MacLean J. The Research Collective: Bridging the Chasm. Healthcare Policy. 2006;1(4):82–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays N., Pope C., Popay J. Systematically Reviewing Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence to Inform Management and Policy-Making in the Health Field. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2005;10(Suppl. 1):7–20. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquet R. Les Réseaux locaux de services : de la vision à l’action. Allocution prononcée dans le cadre du « Rendez-vous des RLS ». Montréal, 21 avril 2005. 2005.

- Pawson R., Greenhalgh T., Harvey G., Walshe K. Methods of Synthesis: Making It Useful for Evidence-Based Management and Policy Making. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2005;10(1):21–34. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineault R., et al. The Research Collective: A Practical and Efficient Tool for Producing Research Syntheses. 2006 (submitted) [Google Scholar]

- Pineault R., Tousignant P., Roberge D., Lamarche P., Reinharz D., Larouche D., Beaulne G., Lesage D. Research Collective on the Organization of Primary Care Services in Quebec. Summary Report. 2005 Retrieved April 11, 2007. http://www.greas.ca .

- Pineault R., Tousignant P., Roberge D., Lamarche P., Reinharz D., Larouche D., Beaulne G., Lesage D. The Research Collective: A Tool for Producing Timely, Context-Linked Research Syntheses. Healthcare Policy. 2006;1(4):58–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon T.A. Making Evidence Synthesis More Useful for Management and Policy-Making. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2005;10(Suppl. 1):1–5. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield D., Denyer D., Smart P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. British Journal of Management. 2003;14:207–22. [Google Scholar]

- Walshe K., Randall T.G. Evidence-Based Management: From Theory to Practice in Health Care. Milbank Quarterly. 2001;79(3):429–57. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]