Abstract

In order to address long healthcare waits, political and professional groups have recommended sending patients to other provinces for diagnostic procedures or treatment. We investigated the feasibility of such recommendations, specifically, whether residence in one province can impede access to MRIs in another province. We contacted all public MRI facilities in Canada and found no difference in wait times between prospective in- and out-of-province patients, although wait times were highly variable from province to province. Over one-fifth (19/86=22%) of centres imposed barriers for out-of-province patients to access care. We discuss several jurisdictional, financial and logistic considerations regarding the feasibility and appropriateness of implementing a national strategy of interprovincial patient transfer for healthcare.

Abstract

Afin de réduire le problème des temps d’attente en soins de santé, des groupes politiques et professionnels ont recommandé d’envoyer des patients se faire traiter dans d’autres provinces. Nous nous sommes penchés sur la faisabilité d’une telle recommandation, plus précisément sur la question à savoir si le fait de résider dans une province donnée peut entraver l’accès à des tests d’imagerie par résonance magnétique dans une autre province. Nous avons communiqué avec tous les établissements pu-blics qui offrent des tests d’IRM au Canada et n’avons trouvé aucune différence dans les temps d’attente entre les patients potentiels, que ceux-ci soient dans la province ou à l’extérieur de celle-ci. Cependant, plus d’un cinquième (19/86 = 22 %) des centres ont imposé des obstacles aux patients de l’extérieur de la province qui cherchaient à avoir accès aux soins. Nous abordons plusieurs questions liées aux secteurs de compétence, d’ordre financier et de nature logistique en vue de déterminer s’il est possible d’instaurer une stratégie nationale pour le transfert interprovincial de patients qui cherchent à obtenir des soins de santé.

Timely access to healthcare is a major concern for Canadians, and healthcare groups, politicians and physicians alike have all been battling the issue (Sanmartin 2003; The Arthritis Society 2005; The Wait Time Alliance 2005; Esmail and Walker 2002). The Wait Times Alliance (WTA) was established in fall 2004 as a result of physicians’ concerns about Canadians’ access to healthcare, with the aim of providing advice to governments on medically acceptable wait time benchmarks. Indeed, the issue of lengthy waits for high-technology, elective medical services in the five priority areas (cancer, cardiac care, diagnostic imaging, joint replacement and sight restoration) agreed to by First Ministers in their September 2004 10-Year Plan to Strengthen Health Care has assumed a leading role in discussions about health policy in Canada.

Concerns about accessibility may drive Canadians – even those living in a province that boasts shorter waits – to search for care elsewhere (Korcok 1993; Bell et al. 1998; Coyte et al. 1994). In fact, recent statements from the WTA as well as the federal Conservative Party platform for the 2006 election suggest that patients and their healthcare providers should seek out-of-province care if it is not available in a timely manner in their home province (The Wait Time Alliance 2005; Patient Wait Times Guarantee 2006). Moreover, a Canadian Medical Association (CMA) survey released in August 2006 found that 84% of Canadians and 85% of doctors value “an interprovincial fund that would pay for patients to be sent to different Canadian jurisdictions for care when the wait in their home jurisdiction exceeds the benchmark for their procedure” (Sylvain 2006). The CMA has been lobbying for such a fund for more than two years.

The portability provisions of the Canada Health Act (CHA) at first glance may appear to contravene these suggestions, as they do not entitle a patient to seek services in another province; rather, they enable patients that are temporarily absent to receive necessary urgent or emergent services (CHA 1984). However, the Act further states that “in some cases coverage may be extended for elective service in another province.” The CHA also emphasizes reasonable access to services on “uniform terms and conditions, unprecluded, unimpeded, either directly or indirectly” (CHA 1984). It is the relative inaccessibility of procedures that may entitle patients to receive coverage for elective services in other provinces, and even “shop around” for healthcare. Both the portability and accessibility clauses of the CHA aim to provide insured Canadians with the security to maintain their health without impediment. It is this premise upon which our study is grounded.

We tested whether residence in one province affects access and wait times for elective tests in another province. Although each of the five priority areas is important, we narrowed the scope of our study and focused on MRI scans for several reasons. MRIs require only that the patient present to the facility for a period of hours and are thus simpler to complete than more complex care processes identified with long waits, such as cancer surgery, joint replacement and cardiac procedures. For this study, we assumed the role of a patient searching for a shorter wait for a medically necessary yet elective MRI.

Methods

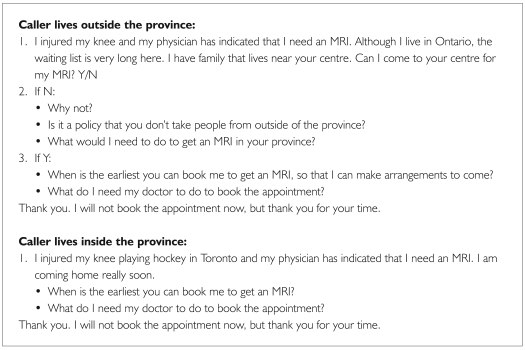

We contacted all publicly funded, adult MRI facilities in Canada between January and August 2005 (CIHI 2004). No private centres were contacted. Two phone calls to each centre were made with a standardized script to book an MRI test of the knee: one with the caller assuming in-province residence, the other with the caller assuming out-of-province residence (Figure 1). The order of the two calls was randomized, and precautions were taken to diminish the chance of voice recognition by the booking agent. This scenario mimics that of a low-priority elective test with a long wait that might drive a patient to search for shorter waits in another province. We assessed the difference between MRI waiting times for in-province compared to out-of-province patients, as well as the number and types of restrictions placed on out-of-province patients. Ethics approval was obtained from the St. Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board.

FIGURE 1.

Sample telephone script

Results

Eighty-six of 98 (88% overall response rate) MRI centres across the country responded to inquiries. Twelve centres would not respond, despite multiple attempts. The median provincial waiting times for MRIs ranged from five weeks in Nova Scotia to 26 weeks in Saskatchewan. For centres that accepted patients from other provinces, there was no difference in estimated MRI waiting times between patients residing in the same province compared to patients living outside the province (17 weeks same province vs. 17 weeks extra-provincial, P>0.2).

Over one-fifth (18/86=21%) of centres imposed one of four types of barriers to accessing care for out-of-province patients. These included (1) four centres that refused to treat out-of-province patients, (2) three centres that demanded payment from the patient prior to the MRI, (3) nine centres that required referrals from physicians living within the province or from the specific centre and (4) three centres that required a written guarantee that the home province would pay for the MRI prior to its administration. All but one centre imposed a single restriction. These policies were institution-specific and were not provincially based, as there was wide variation among centres within the same province.

Not all the centres were unreceptive towards out-of-province patients. Two facilities indicated that their system was designed to deal with out-of-province patients and they “appreciated the extra revenue.”

Interpretation

In theory, the adoption of a national policy of interprovincial access to MRIs is feasible, as is signified by the finding that the majority of MRI centres would initially book examinations for out-of-province patients. However, the responses from less accommodating centres highlight that this willingness may only reflect naive experience, since presently this is not a common occurrence for most facilities. Our findings of fairly widespread access, therefore, may not be valid. Nevertheless, if a national policy of interprovincial access were adopted, we identified four barriers to consider. These barriers stem from jurisdictional, financial and logistic issues that would have to be addressed in order for the program to be successful.

One jurisdictional issue relates to the requirement that a number of MRI centres impose of a referral from a local physician. This process duplicates service, adds longer waits for the test and increases costs. A policy of interprovincial access would require provinces to accept diagnostic requisitions from out-of-province physicians. Such a policy already occurs on a small scale in some referral areas and catchment areas that do not follow provincial boundaries. Indeed, one of the facilities surveyed referred us to a centre with a shorter wait in an adjacent province.

Financial issues may pose more of a challenge, particularly because healthcare falls under provincial jurisdiction, whereas the policy is promoted as a federal strategy. As is recommended by the WTA, the patient’s home province would underwrite the healthcare charges (and possibly associated travel costs), similar to the present practice for rural residents in many provinces. This arrangement would require explicit guarantees for payment from the home province to the provider province. Pushing the argument further, incentives may have to be paid to provider provinces or MRI centres for care. Interestingly, two facilities indicated appreciation for out-of-province examinations because of the extra revenue. The potential for lengthening waits in the receiving province, as well as preferential access for out-of-province residents because of increased remuneration, should be considered. This scenario resembles present situations with third-party healthcare payers and may require regulation of the proportion of care provided to out-of-province residents.

The logistical issues with such a policy are also important. When, in the waiting process, should patients be offered their appointment elsewhere? Should it be when they are presented initially with the long wait, or after they have waited for a prescribed period of time? When formulating operating procedure, care should be taken to avoid having these individuals jump the queue. Maintaining a culture of fairness and transparency with such practice is essential. Moreover, although patients can shop around, many do not have the means or the ability to do so. A streamlined infrastructure to arrange for the movement and direction of patients to appropriate places is required for the sake of efficiency, and can be accomplished.

Given that our analysis is derived from a survey of MRI facilities and not other specified high-technology healthcare resources, our suggestions are preliminary. Data were collected during a brief interval and relied on self-reported wait times and referral policies. Although our sample size was small, we contacted all Canadian centres and had a high response rate.

Radiologic tests such as CT or MRI – which require the patient only to present to the facility for a period of hours – are the most feasible program to consider implementing, as compared to more complex care processes identified with long waits, such as cancer surgery, joint replacement and cardiac procedures. These pose added challenges because they involve initial consultation with providers, hospital stays, long recovery periods, separation of patients from their families and support systems and requisite follow-up. Still, many facilities in the United States that offer this service to Canadians have been able to overcome these issues, albeit on an ad hoc basis. Thus, these programs would experience, at minimum, the same issues that we have encountered for MRIs. A strategy of interprovincial access to healthcare resources that extrapolates our findings to the other areas of high-technology services with lengthy waits would apply only to truly elective care. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that elective healthcare in Canada does not fully cross provincial boundaries.

A policy of interprovincial access to MRIs – and, by extrapolation, other high-technology services – can be achieved with skilled planning and preparation, despite many jurisdictional, financial and logistic barriers. Justification for this policy may be found in the portability and accessibility clauses of the Canada Health Act. However, the political and financial costs would undoubtedly direct resources away from more permanent solutions. The effort required to implement such programs may be large enough to tilt the balance for provincial governments in favour of increased capital expenditures instead of the shuttling of patients to other provinces. The barriers to interprovincial access, although individually surmountable, should cause federal and provincial governments to rethink the strategy of borrowing healthcare from their provincial neighbours and, instead, consider investing in healthcare in their own provinces.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Bell holds a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. We thank Dr. Don Redelmeier for comments and suggestions.

Contributor Information

Giselle Revah, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

Chaim Bell, Faculty of Medicine, Departments of Medicine, Health Policy Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto; Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Department of Medicine, St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON.

References

- The Arthritis Society. Groundbreaking Report on Health Care Wait Times Released. 2005 Apr 4; Retrieved March 24, 2007. http://www.arthritis.ca/toolbox/headline%20news2/default.asp?s=1 .

- Bell C.M., Detsky A.S., Redelmeier D.A. Shopping around for Hospital Services: A Comparison of the United States and Canada. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998 Apr 1;279(13):1015–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.13.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canada Health Act 1984, c. 6, s. 11. Retrieved March 24, 2007. http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/ShowFullDoc/cs/C-6///en .

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Medical Imaging in Canada, 2004. 2004 Retrieved March 24, 2007. http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cw_page=media_13jan2005_e#mic .

- Coyte P.C., Wright I.G., Hawker C.A., Bombardier C., Dittus R.S., Paul J.E. Waiting Times for Knee-Replacement Surgery in the US and Ontario. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331(4):1068–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410203311607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmail N., Walker M. Waiting Your Turn: Hospital Waiting Lists in Canada (12th ed.). The Fraser Institute. 2002 Sep; Retrieved March 24, 2007. http://www.fraserinstitute.ca/shared/readmore.asp?sNav=pb&id=413 .

- Korcok M. Ontario’s Move to Limit Out-of-Province Health Care Spending Pays Off in Big Way. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1993 Feb 1;148(3):425–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Wait Times Guarantee. Conservative Party of Canada. 2006 Retrieved January 6, 2006. http://www.conservative.ca .

- Sanmartin C.A., the Steering Committee of the Western Canada Waiting List Project Toward Standard Definitions for Waiting Times. Healthcare Management Forum. 2003 Jun;:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvain M. MDs Want Wait-Time Talk Translated into Action: Survey. Medical Post. August 22, 2006. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- The Wait Time Alliance, Canadian Medical Association. It’s About Time: Achieving Benchmarks and Best Practices in Wait-Time Management. 2005 Aug; Retrieved March 24, 2007. http://www.caep.ca/002.policies/002-05.communications/2005/050826-report.wait-time-alliance.pdf?stopthewait .