Abstract

Background:

This paper reports on selected findings from the 2005 National Evaluation of the Health Transfer Policy. Three hypotheses were tested, namely: (1) that inequalities in per capita financing exist between First Nations organizations, (2) that variations in per capita funding among communities cannot be explained by variations in the program responsibilities each assumed and (3) that First Nations organizations that transferred in the early 1990s now have access to fewer resources on a per capita basis than those that transferred more recently.

Methods:

We compared (1) the per capita funding for 30 medium-sized communities (population = 401–3,000) that have Health Centres and the 13 similarly sized communities that have Health Stations, (2) program responsibilities and per capita funding for the same 30 communities and (3) the relationship between 2001–2002 per capita funding and the year of transfer for the same communities. We used data provided to us by the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch of Health Canada from 1989 to 2002.

Results:

The results show that differences in per capita funding exist among and within regions. These differences cannot be explained by the responsibilities each community chose to assume. Differences are also related to the year First Nations entered into a transfer agreement.

Conclusions:

We recommend that formula-based financing be adopted to reduce inequalities. Such a formula should reflect needs, population growth and changes in costs of service delivery.

Abstract

Contexte :

Cet article présente des résultats sélectionnés de l’évaluation nationale de la Politique de transfert des services de santé. Trois hypothèses ont été mises à l’épreuve, à savoir, (1) qu’il existe des inégalités dans le financement par habitant entre les orga-nismes des Premières nations, (2) que les variations dans le financement par habitant entre les communautés ne peuvent s’expliquer par les variations dans les responsabi-lités liées aux programmes assumées par chacune (3) que les organismes des Premières nations auxquelles les services de santé ont été transférés au début des années 90 ont maintenant accès à moins de ressources par habitant que celles pour lesquelles ce transfert a été effectué plus récemment.

Méthodes :

Nous avons comparé (1) le financement par habitant pour 30 commu-nautés de taille moyenne (population = 401–3 000) qui ont des centres de santé et 13 communautés de taille semblable dotées de postes sanitaires; (2) les responsabilités liées aux programmes et le financement par habitant pour les mêmes 30 communautés et (3) la relation entre le financement par habitant en 2001–2002 et dans l’année de transfert pour ces mêmes communautés. Ces hypothèses ont été vérifiées à l’aide de données de 1989 à 2002 qui nous ont été fournies par la Direction générale de la santé des Premières nations et des Inuits de Santé Canada.

Résultats :

Les résultats montrent qu’il existe des différences dans le financement par habitant d’une région à l’autre et au sein d’une même région. Ces différences ne peuvent pas être expliquées par les responsabilités que chaque communauté a choisi d’assumer. Les différences tiennent également à l’année où les Premières nations ont conclu une entente de transfert.

Conclusions :

Nous recommandons l’adoption d’un financement axé sur une formule afin de réduire les inégalités. Une telle formule devrait refléter les besoins, la croissance démographique et les coûts changeants de la prestation des services.

The Health Transfer Policy (HTP)1 was introduced in 1989 to support First Nations’ aspirations to design health programs, establish services and allocate funds according to community health priorities (National Health and Welfare and Treasury Board of Canada 1989). Before 1989, the majority of programs and services were delivered directly on-reserve by the Medical Services Branch, which is now known as the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch of Health Canada (hereafter, FNIHB).

The HTP was a natural progression from the 1979 Indian Health Policy, with its stated goal of achieving “an increasing level of health in Indian communities, generated and maintained by the Indian communities themselves” (Health Canada 2000). This orientation reflected an important policy shift within the federal government, from caretaking and management to development (Hawthorn 1966), and active participation in program planning and delivery, particularly in the area of health (Booz•Allen & Hamilton Canada 1969; National Health and Welfare 1979; Berger 1980; Bégin 1981). The shift reflected years of lobbying by First Nations to secure more control over all sectors of their lives. Two programs, the Community Health Representatives (known as CHRs) and the National Native Alcohol and Drugs Addictions Program (NNADAP), were administered by First Nations since their creation, under yearly contribution agreements.2 The HTP allowed the expansion of the number of services and programs that could be administered by First Nations, and the consolidation of the funding for these services under a single flexible agreement that could be signed for three to five years.

As of 2003, FNIHB reports that 78% of the eligible 603 First Nations and Inuit communities have chosen to exercise more direct control over their community-based health services (Health Canada 2003a). Over time, however, concerns over sustainability have been raised by both FNIHB and First Nations (Health Canada [FNIHB] 1999a; Assembly of First Nations 2002). Specifically, First Nations have reported that funding (1) does not match needs, (2) does not provide for population growth and (3) does not take into account off-reserve and non-status users (Lavoie et al. 2005).

The Centre for Aboriginal Health Research of the University of Manitoba recently completed a national evaluation of the Health Transfer Policy. The purpose of this paper is to report on three hypotheses that were tested in the context of this study, namely:

that inequalities in financing exist between First Nations organizations, both between and within regions

that variations in per capita funding between communities cannot be explained by variations in the program responsibilities each assumed

that First Nations organizations that transferred early in the process now have access to fewer resources on a per capita basis than those that transferred more recently.

The findings presented in this paper will inform a discussion on the constraints and policy options associated with the delivery of on-reserve primary healthcare services.

Background

The original impetus for the development of health services to First Nations came from the settlers who arrived at the turn of the century to farm the land. They found themselves living close to Indian reserves where appalling health conditions prevailed. Fear of epidemics, mostly tuberculosis, led the federal government to begin to invest funding in First Nations health services, with the hiring of a General Medical Superintendent in 1904 and a mobile nurse visitor program in 1922 (Waldram et al. 2006). The first federally funded on-reserve nursing station was set up on the Peguis reserve (Fisher River Agency, Manitoba) in 1930. The creation of the Department of National Health in 1944 led to a sustained expansion of health services for First Nations (Young 1984).

Currently, nearly all First Nations reserves have access to services delivered in a facility located on-reserve. These facilities, called Health Offices, Health Stations, Health Centres or Nursing Stations, depending on the level of care provided,3 offer primary healthcare services delivered by nurses and local Community Health Representatives. Other services include addiction counselling and medical transportation. Physicians funded by the province visit these communities on a regular basis. Patients requiring secondary, tertiary or emergency care are transported to the nearest provincial referral centre (Lavoie 2003). It has been repeatedly documented that the federal and provincial systems operate without joint planning, and that gaps have emerged as a result (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples 1996; Romanow 2002).

The HTP was based on the idea of transferring identified pre-existing services located at the community (level 1), the zone (where they existed, level 2) and the regional levels (level 3).

In 1994, FNIHB broadened opportunities for community control by introducing the Integrated Community–based approach (Health Canada [FNIHB] 1999b). The intent was to provide flexible alternatives to the one-size-fits-all transfer model. Table 1 shows the main differences between the two models. Although the integrated model provided somewhat less flexibility, some bands, especially in Alberta, preferred this model because they believed that this option did not infringe on their treaty rights. Some communities have been concerned that the transfer process pushes communities to accepting a model that simply side-steps more important discussions of treaty rights in areas of health (Culhane Speck 1989; Favel-King 1993). Others saw it as lower risk and as an opportunity to learn to manage health services before entering into a transfer agreement. In addition, small communities were not eligible to transfer because of diseconomies of scale (Health Canada Medical Services Branch 1991). The integrated model provided them with a new opportunity for participation.

TABLE 1.

The continuum of transfer

| Name of Agreement(s) | CCA-Integrated, Integrated Agreement | CCA-Transfer, Transfer Agreement |

| Duration | Phase 1: Up to 1 year Phase 2: Up to 5 years |

3 to 5 years |

| Description | All transferable programs chosen by the community under a single 3 to 5 year agreement Non-transferable programs under separate contribution agreements |

All transferable programs chosen by the community under a single 3 to 5 year agreement Non-transferable programs under separate contribution agreements |

| Funded Planning Phase | Development of work plan in Phase 1 (12 months) The completed work plan must contain four components of a Community Health Plan |

A 21-month planning process resulting in development of 12 components of the 15 required for a Community Health Plan Remaining 3 components are done in the first year of implementation |

| Ability to Move Funding between Programs | Once work plan is in place, cannot reallocate unless prior written approval of FNIHB | Yes |

| Ability to Carry over Financial Resources | No. Unexpended resources must be returned to FNIHB. | Yes, for use on health-related expenditures |

Communities could opt to:

take on and deliver some or all community-based, zone and regional services

take the funding and purchase the services from FNIHB, a provincial authority or provider or

continue to receive services directly from FNIHB.

As shown in Figure 1, these choices resulted in communities selecting a different complement of services, based on local priorities, capacity, community size, location and other factors.

FIGURE 1.

Choices in community services

Calculating resources meant listing services to be included in an agreement and establishing costs. For first-level services, resources were identified based on historical expenditures. The allocation of zone and regional personnel was somewhat more subjective. Each region was provided with a list of existing regional and zone positions and asked to identify the positions that were to be identified as Indian Health and therefore transferable (memorandum, January 28, 1992). Selected positions were then allocated to transferring communities that chose to take responsibility for the associated program. There was no cross-regional baseline established to ensure that zone and regional services were funded and structured in a similar manner across regions (Lavoie et al. 2005).

Methods

The overall national evaluation took place from August 2003 to January 2005 and was overseen by a National Advisory Committee with representatives from the Assembly of First Nations, the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and FNIHB. Ethical approval for the evaluation was secured from the University of Manitoba.

The financial analysis we conducted used three separate administrative databases. The Health Funding Arrangements database (referred to hereafter as the HFA database, Health Canada [FNIHB] 2003d) is a comprehensive administrative tool detailing funding and program responsibilities for transfer and integrated agreements, and amendments signed by First Nations organizations after the implementation of the Health Transfer Policy. The data set contained financial information from 1989 to mid-2003. The scope of the evaluation was set at 1989 to 2002, to ensure access to full data sets. The database does not contain information on contribution agreements for non-transferable programs signed by communities.4

The HFA database was used in conjunction with a facility designation database (Health Canada [FNIHB] 2003a) that defines the types of services First Nations organizations provide, based on remoteness and accessibility of provincial services.5 A third database, the CWIS-CPMS 2001/2002, was used to characterize the population served by on-reserve health services, according to Health Canada (Health Canada [FNIHB] 2004).

We compared the per capita funding for communities that signed a transfer agreement as a stand-alone community before 2001/02 in order to test hypothesis 1 – that per capita funding differs among similar communities, both within and between regions. First Nations health organizations were divided into three clusters for analysis. Cluster 1 contains 231 communities that signed an integrated or transfer agreement as a stand-alone community. Cluster 2 recipients include organizations that serve more than one community (36 agreements serving a total of 133 communities) with different facility designations. This grouping caused a methodological problem in apportioning the funding received among different communities.6 Cluster 3 organizations (53 agreements serving 144 communities) have complex patterns of agreements that are difficult to disentangle.7 Based on the information available, only Cluster 1 organizations could be included in the analysis.

Of the original 231 organizations included in Cluster 1, only 98 were retained. Others were dropped because:

they signed a transfer or integrated agreement either midway through or after the study period (2001/02, N=120) and/or

for some organizations, the information provided in the HFA database was ambiguous (N=13).

Table 2 shows some key characteristics for the remaining 98 organizations. The final sample shared a number of characteristics that affected financial allocations, including facility designation, administrative arrangement model (transfer or integrated agreement) and community size.

Table 2.

Breakdown of Cluster 1

| Integrated | Transfer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Population | 0–100 | 100–400 | 400–3,000 | 100–400 | 400–3,000 | 3,000–5,000 | > 7,000 |

| Health Office | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Health Station | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 13 | 0 | 1 |

| Health Centre | 1 | 1 | 8 | 9 | 30 | 2 | 1 |

| Nursing Station | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| Hospital | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1 | 3 | 13 | 17 | 59 | 3 | 2 |

Only transferred communities with populations between 401 and 3,000 and served by a Health Centre were numerous enough and broadly distributed to allow for regional comparisons (N=30). Similarly sized transferred communities with Health Stations provided additional insights (N=13).

All funding provided by FNIHB for programs and administration under a transfer agreement was accounted for and capitated. Capital costs were omitted because allocation depends on the age and condition of the Health Canada–owned facilities. These findings were compared to the regional FNIHB expenditure for transfer on a per capita basis.

Per capita funding was compared to program responsibilities to test hypothesis 2 – that differences in funding cannot be explained by differences in program responsibilities. This analysis used the same 30 Health Centres selected above.

An analysis of 2001/02 per capita funding based on the year of transfer was conducted for the same 30 Health Centres to identify whether access to funding was affected by year-to-year shifts in policy or funding to test hypothesis 3 – that First Nations that transferred early have lower per capita funding than those that transferred more recently.

To ensure validity, all findings were triangulated with other sources of data collected in the course of the national evaluation, namely, 66 interviews conducted with FNIHB employees, 190 interviews conducted with administrators of First Nations and Inuit health organizations and a review of contribution agreements and amendments from 28 selected First Nations and Inuit organizations that transferred in the early 1990s (national cross-section). Internal correspondence and documents collected from FNIHB’s regional offices and from headquarters were also reviewed for insights.

Results

Hypothesis 1:

Inequalities in financing exist among First Nations organizations, both between and within regions

Table 3 shows variations in transfer funding for 30 Health Centres located in medium-sized communities. The per capita funding allocated ranged from $430 to $1,418. Manitoba and Atlantic First Nations organizations appear to be funded at a lower level than those of other regions.

TABLE 3.

2001/02 variations in per capita transfer funding including transferable programs for health centres in medium-sized communities, across regions (Health Canada [FNIHB], 2003c, 2004)

| 2001/02 Funding per Capita, Using 2001/02 Figures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FNIHB regions | N | Mean | Median | Range | SD |

| Pacific (British Columbia) | 5 | $890 | $887 | $233 | $96 |

| Alberta | 1 | N/A because of small number of cases | |||

| Saskatchewan | 4 | $738 | $729 | $469 | $216 |

| Manitoba | 4 | $610 | $633 | $104 | $50 |

| Ontario | 4 | $780 | $728 | $336 | $150 |

| Quebec | 8 | $847 | $761 | $894 | $350 |

| Atlantic | 4 | $544 | $494 | $324 | $144 |

| Total/Average | 30 | $759 | $734 | $337 | $144 |

Table 4 shows variations in transfer funding for 13 Health Stations located in medium-sized communities. In this case, per capita funding ranged from $393 to $1,267.

TABLE 4.

2001/02 variations in per capita transfer funding including transferable programs for health stations in medium-sized communities, across regions (Health Canada [FNIHB], 2003b, 2004)

| 2001/02 Funding per Capita, Using 2001/02 Figures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FNIHB regions | N | Mean | Median | Range | SD |

| Pacific (British Columbia) | 8 | $918 | $893 | $511 | $153 |

| Saskatchewan | 2 | $591 | $591 | $396 | $280 |

| Ontario | 3 | $756 | $790 | $148 | $80 |

| Total/Average | 13 | $755 | $758 | $352 | $171 |

Hypothesis 2:

Per capita funding is not proportional to the program responsibilities shouldered by First Nations organizations

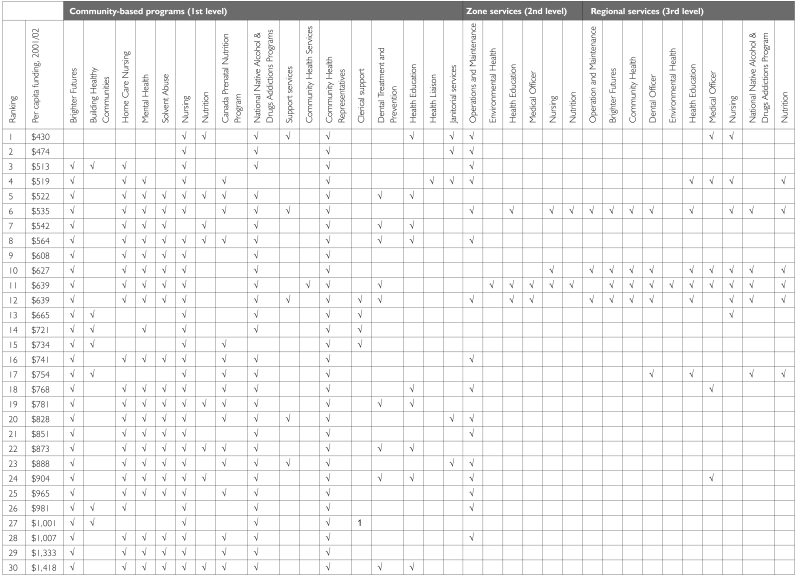

Table 5 shows program uptake for the 30 Health Centres included in Table 3. The first column represents the rank of each included community, based on per capita funding; column 2 reports per capita funding, and subsequent columns represent first- (community-based), second- (zone-based or supervisory) and third-level (regional or planning and advisory) services included in each transfer agreement.

Table 5.

Ranking of sampled communities from least well resourced to best resourced on a per capita basis, showing program uptake under transfer agreement

In theory and based on the HTP, programs marked with a √ are those that were transferred to First Nations. Programs without a √ remain an FNIHB responsibility and are termed “residual roles.” As shown, the level of funding per capita does not correspond with the program uptake under the transfer agreement. While the range of per capita funding spans $430 to $1,418, better-resourced communities in fact were less likely to have assumed responsibility for second- and third-level services than communities resourced around $500 to $600 per capita. Program uptake could not be attributed to more specific community sizes or FNIHB region.

In practice, for all programs other than community health nursing, Community Health Representatives, the National Native Alcohol and Drug Addictions Program, Environmental Health, and clerical and janitorial support, programs may have been added to the list of transferred responsibilities to ensure the financial sustainability of the community-based programs. Communities that show zone and regional responsibilities received funding for only a small fraction of a person-year, making the hiring of someone to offer this service impractical (Lavoie et al. 2005). Once a function is transferred, however, FNIHB is no longer obligated or resourced to provide the service.

Hypothesis 3:

That First Nations organizations that transferred early in the process now have access to fewer resources on a per capita basis than those that transferred more recently

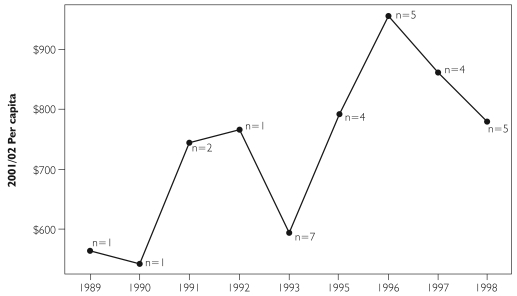

It has long been assumed by First Nations that communities that entered into transfer early on now have access to lower per capita funding than those who transferred more recently, because the level of funding has not been adjusted for population growth (Assembly of First Nations 2002). In fact, this is borne out by our analysis (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

2001/02 per capita funding, based on year of transfer

Discussion

Different levels of funding may be required to accommodate differences in community characteristics, level of capacity and needs. Thus, some variation in funding is to be expected and may be seen as appropriate. A higher level of variation within a region (for example, Table 3, Quebec, with a standard deviation of $350 per capita) suggests that funding may be provided at different levels within a region in response to higher needs in some communities. A lower level of variation within a region (for example, Table 3, Manitoba, with a standard deviation of $50 per capita) suggests either a lower level of variation in needs across the region or less regional flexibility in matching needs with funding.

However, the level of variation shown in Tables 3 and 4 raises the question of whether there may be funding inequities. The results of this study show that differences in per capita funding exist among and within regions, and that these differences cannot be explained by the responsibilities each community chose to take on (Table 5). This finding alone does not support the claim of inequity; it simply demonstrates that differences in funding exist that cannot be explained by program responsibility. Perhaps more problematic is the observation that differences in per capita funding exist among First Nations, depending on the year they entered into a transfer agreement.

As a community transferred, initial levels of per capita funding were determined based on program funding in the previous years. The base levels of funding may have differed for at least four reasons.

First, regional FNIHB budgets and staffing profiles developed over time, based on regional practices and circumstances. There was no rebasing exercise to ensure equity across FNIHB regions before rolling out the HTP.

Second, transferable resources were based on expenditure level the year(s) before transfer. Some variations are due to differences in the salary of nurses and other staff, resulting from (a) variations in federal government salary scales from one region to the next for the same position; (b) salaries that may have included overtime for some Health Centres and not others, reflecting the level of services offered the year(s) before transfer and regional FNIHB management practices concerning overtime; (c) some regions that transferred positions at the top of the salary scale to maximize viability, while others did not because of limited resources; and (d) salaries that were likely higher in communities with long-standing staff.

Third, the year of transfer seems to have been significant. In 1994, the federal government implemented budget cuts across all federal departments in an effort to reduce its deficit. Bands that transferred that year appear to have been able to access fewer resources on a per capita basis. This level of funding was thereafter entrenched, and not negotiable.

Fourth, some First Nations respondents have suggested that negotiation skills may have played a role. This explanation, however, tends to be rejected by FNIHB respondents (Lavoie et al. 2005).

It is clear from the results reported here that the HTP funding was based on the assumption that historical expenditures closely reflected needs. This may very well have been the case in some circumstances. However, as long as FNIHB delivered services directly, adjustments to the level of services could be made as needed. Once First Nations signed a transfer or an integrated agreement, however, they effectively became locked into a level of funding based on historical expenditures. Although some evidence of adjustments to fit circumstances was documented (Lavoie et al. 2005), these opportunities were limited and short lived. Inequalities were left to grow unmonitored. Over time, even small differences in per capita funding based on historical circumstances are exacerbated when there is no ongoing commitment to adjust the level of funding to fit documented changes in circumstances.

It is important to note that our findings alone cannot be used to support claims of over- or under-investment in on-reserve primary healthcare. There exists, however, an emerging body of evidence showing a disproportionate utilization of secondary and tertiary care services for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions by First Nations, suggesting barriers to access primary healthcare services (Martens et al. 2002, 2005; Shah et al. 2003).

The HTP, then, has had two paradoxical effects. On the one hand, First Nations’ participation in planning and delivering services designed to reflect local needs and priorities offers considerable potential for improving health outcomes. On the other hand, funding formulas that are not revisited regularly to ensure that per capita funding levels reflect the needs of the community undermine benefits that may emerge from greater participation.

There are two possible policy responses to these effects. At the very least, and in the short run, FNIHB should examine the differences in per capita funding within and among regions, particularly among similar kinds of communities with identical facility designations, and determine whether the differences that we have documented are justified by special, local circumstances. More important, however, is to ensure that the levels of funding built into the HTP truly reflect need rather than historical circumstances.

The health services delivered on-reserve are essential services and an integral part of the Canadian healthcare system. First Nations have long advocated for a financing formula that reflects variations in needs, population growth and escalating costs (Assembly of First Nations 1988). We add that this formula should complement provincial healthcare services accessible to First Nations and reflect Health Canada’s current commitment to comprehensive primary healthcare as one of the pillars of the Canadian healthcare system.

Realizing that this objective is challenging, the authors, in partnership with the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, Manitoba Health and the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, are currently involved in a Manitoba-specific research project that will investigate secondary and tertiary health service utilization patterns for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions for the on-reserve First Nations population, with the objective of identifying where investments in primary healthcare services may best serve unmet needs. The results of the study can also be used as a step towards identifying a basket of essential primary healthcare services necessary to address existing needs. Together with more comprehensive assessments of morbidity and demographic changes, these analyses will contribute to the development of needs-based financing for First Nations communities, an approach that is ultimately the only way to address the concerns identified in this paper.

The same policy is also known as the Health Services Transfer Policy (Health Canada 2003b).

Contribution agreements were used to transfer the responsibility for the delivery of programs to First Nations. These mechanisms, however, did not allow communities to re-prioritize or redirect health resources.

Health Offices operate in non-isolated and semi-isolated communities with populations of 0 to 750 and with good access to provincial services. These facilities provide part-time access to prevention and health promotion activities. Health Stations operate in remote isolated to semi-isolated communities with populations over 100. These facilities provide part-time access to screening, prevention and health promotion activities. Health Centres operate in non-isolated and semi-isolated communities with populations over 100 and that are less than 350 km from a service centre. They provide emergency, screening and prevention services five days a week. Nursing Stations operate in remote or isolated communities with populations over 500 and where access to services is limited. They provide emergency, prevention and out-patient treatment services 24/7.

Examples of “transferable programs” include the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program, Brighter Futures and Building Healthy Communities. Examples of “non-transferable programs” include the Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative and the Home and Community Care Program. As a rule of thumb, most programs introduced after 1994 cannot be transferred, i.e., included under the transfer agreement, and are instead funded through separate contribution agreements, with considerably less flexibility in terms of priority setting and financial allocation.

See note 3.

The funding formula differs depending on facility designation. Comparability, therefore, became problematic.

For example, one Tribal Council provides different first- and second-level services, depending on its affiliated bands’ preferences. Some of its bands also have their own first-level services agreement for all services except nursing. There is no basis for establishing comparability.

Contributor Information

Josée G. Lavoie, University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, BC.

Evelyn Forget, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB.

John D. O’Neil, Faculty of Health Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC.

References

- Assembly of First Nations. Special Report: The National Indian Health Transfer Conference. Ottawa: Author; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Assembly of First Nations. Presentation Notes to the Commission on the Future of Healthcare in Canada. Ottawa: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bégin M. Transfer of Health Services to Indian Communities. Discussion paper. Ottawa: National Health and Welfare; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Berger T.R. Report of the Advisory Commission on Indian and Inuit Health. Ottawa: National Health and Welfare; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Booz•Allen & Hamilton Canada Ltd. Study of Health Services for Canadian Indians. Ottawa: Author; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Culhane Speck D. The Indian Health Transfer Policy: A Step in the Right Direction, or Revenge of the Hidden Agenda? Native Studies Review. 1989;5:187–213. [Google Scholar]

- Favel-King A. The Treaty Right to Health. In: Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, editor. The Path to Healing: Report of the National Round Table on Aboriginal Health and Social Issues (pp. 120–29) Ottawa: Ministry of Supply and Services Canada; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorn H.B. A Survey of the Contemporary Indians of Canada: Economic, Political, Educational Needs and Policies (The Hawthorn Report). Part 1. Ottawa: Indian Affairs Branch; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Indian Health Policy 1979. 2000 Retrieved April 11, 2007. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fnih-spni/services/indi_health-sante_poli_e.html .

- Health Canada. Annual Report, First Nations and Inuit Control 2002–2003: Program Policy Transfer Secretariat and Planning Directorate, Health Funding Arrangements. Ottawa: Author; 2003a. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. First Nations and Inuit Health Program Compendium. Ottawa: Health Canada First Nations and Inuit Health Branch; 2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada [FNIHB] Ottawa: Author; 1999a. Discussion Paper on Transfer Investment/Reinvestment. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada [FNIHB] Transferring Control of Health Programs to First Nations and Inuit Communities, Handbook 1: An Introduction to All Three Approaches. Ottawa: Health Canada, Program Policy Transfer Secretariat and Planning Health Funding Arrangements; 1999b. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada [FNIHB] Facility Designation database, unpublished data. 2003a.

- Health Canada [FNIHB] Health Funding Arrangements database, unpublished data. 2003b.

- Health Canada [FNIHB] Health Funding Arrangements database, unpublished data. 2003c.

- Health Canada [FNIHB] Health Funding Arrangements database, unpublished data. 2003d.

- Health Canada [FNIHB] Community Planning Management System (CPMS) 2004.

- Health Canada Medical Services Branch. Critical Mass Policy. Ottawa: Author; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie J.G. The Value and Challenges of Separate Services: First Nations in Canada. In: Healy J., McKee M., editors. Health Care: Responding to Diversity. London, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie J.G., O’Neil J., Sanderson L., Elias B., Mignone J., Bartlett J., et al. The National Evaluation of the Health Transfer Policy. Final Report. Winnipeg: Manitoba First Nations Centre for Aboriginal Health Research; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Martens P., Bond R., Jebamani L., Burchill C., Roos N., Derksen S., et al. The Health and Health Care Use of Registered First Nations People Living in Manitoba: A Population-Based Study. Winnipeg: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Department of Community Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Martens P.J., Sanderson D., Jebamani L. Health Services Use of Manitoba First Nations People: Is It Related to Underlying Need? Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2005;96(Suppl. 1):S39–S44. doi: 10.1007/BF03405315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Welfare. Indian Health. Discussion paper. Ottawa: Author; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Welfare and Treasury Board of Canada. Memorandum of Understanding between the Minister of National Health and Welfare and the Treasury Board Concerning the Transfer of Health Services to Indian Control. Ottawa: Author; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Romanow R.J. Building on Values. The Future of Health Care in Canada. Final Report. Ottawa: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. People to People, Nation to Nation: Highlights from the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shah B.R., Gunraj N., Hux J.E. Markers of Access to and Quality of Primary Care for Aboriginal People in Ontario, Canada. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:798–802. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldram J.B., Herring D.A., Young T.I. Aboriginal Health in Canada: Historical, Cultural and Epidemiological Perspectives (2nd ed.) Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Young T.K. Indian Health Services in Canada: A Sociohistorical Perspective. Social Science and Medicine. 1984;18:257–64. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]