Abstract

The chimeric small animal model system wherein the severe combined immunodeficient mouse is transplanted with human fetal thymus and liver tissues (SCID-hu Thy/Liv) has been used in different areas of experimental research [1]. A living model system offers the advantage that studies of longer duration than in vitro can be performed. Here we discuss the importance of experimental in vivo studies and how well the data generated using this model system correlates with epidemiological studies from HIV-positive humans. Patients with HIV-1 infection often suffer from cytopenias, with thrombocytopenia typically having an earlier onset than anemia and neutropenia. The cytopenias in patients may be caused by virus effects at the stem cell level, or the mature blood cell level, or by other factors like medications used to treat the infection. Several studies preformed in SCID-hu animals show that the function of human hematopoietic progenitor stem cells are indirectly affected by HIV-1 infection. Colony forming activity (CFA) assays on hematopoietic progenitor cells derived from SCID-hu animals and human bone marrow have been performed as a measure of progenitor cellular function, and HIV-1 infection decreased CFA in multiple lineages that include megakaryoid, erythroid and myeloid types. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) partially and transiently reduces the inhibition of multilineage CFA and data suggest that HIV-1 indirectly affects stem cell differentiation into multiple lineages. The cojoint human hematopoietic organ of this small animal model system recapitulates the inhibitory effects of HIV-1 infection on the function of progenitor cells of the human bone marrow. Thus the SCID-hu (Thy/Liv) model is a useful in vivo system for preclinical translational research towards development of stem cell therapies in HIV infection.

Introduction

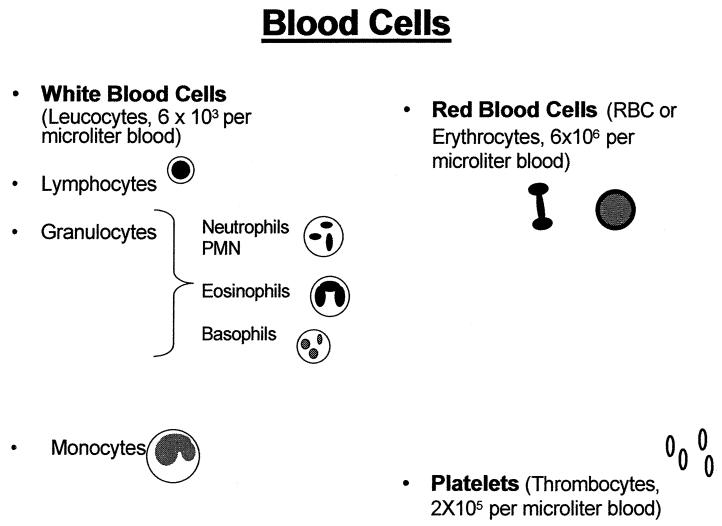

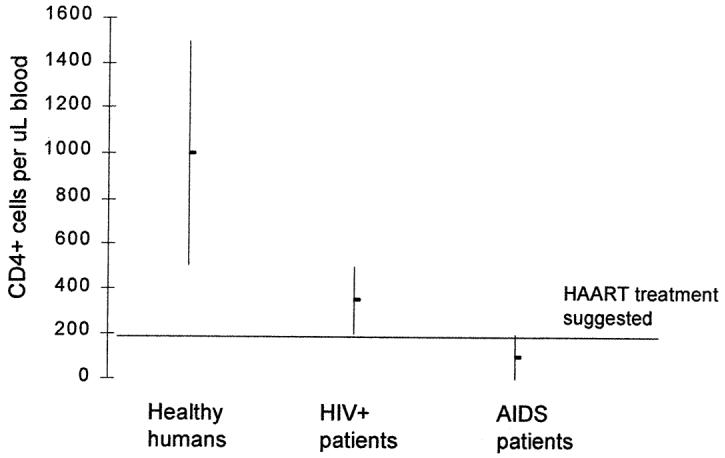

The acquired immunodeficiency virus syndrome (AIDS) was first recognized in 1981 as a disease caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Since then it is estimated that about 40 million people have been infected by HIV and 5 million new HIV infections occur every year making the disease HIV/AIDS, a major health problem. HIV progressively destroys the body’s ability in fighting infections. By the destruction and/or functional impairment of the leukocytes of the immune system, it can almost completely deplete CD4+ T-cells. Healthy humans have approximately 6,000 white blood cells in one cubic mm (microliter, μL) blood, of which 600-1,500 of these cells are lymphocytes. Eighty percent of the lymphocytes are CD4 positive (CD4+) T-cells (Figures 1 and 2). The clinical diagnosis of AIDS is based on the CD4+ T-cell count; a CD4+ T-cell count lower than 200 cells/μL qualifies for the diagnosis of AIDS (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Mature cells appearing in the blood of healthy humans.

Figure 2.

Mature white blood cells in the blood of healthy humans. The mature T-cells are CD4+ lymphocytes, the CD8+ cells are less mature. The CD4+ cells are depleted by HIV-1 infection.

Figure 3.

HIV-1 infection depletes the CD4+ T-cells, when there are fewer than 200 CD4+ T cells/μL of blood the diagnosis is AIDS is set. Progression of HIV-1 to AIDS can be slow even in the absence of antiretroviral therapy. The median time of progression from HIV infection to AIDS is 9 to 10 years, but the median survival time after developing AIDS is less than 1 year. When HIV can be treated with anti-viral therapy, treatment is recommended to commence when the CD4+ cells decrease below 200 cells/uL blood.

Treatments that reduce virus levels in the blood have been developed with the goal of these anti-viral treatments is to suppress the HIV viral load to a minimum possible level and for a maximum possible period. Low virus levels in the blood are effective in reducing complications from infection and in delaying the onset of AIDS. HIV infection involves integration of new genetic material into cellular chromosome, making the virus, a part of the cell. Infected cells release the virus into blood stream and the free virus is targeted by anti-viral treatment, but as the cells divide the virus also replicates in the dividing cells. Intracellular virus is not easily be targeted by antiviral treatment. Thus virus reservoirs can be built up in different tissues even in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), especially in tissues with low blood supply.

Cytopenias other than the lymphopenia, for example, low levels of platelets, red blood cells (RBCs), and neutrophils, are serious complications in HIV-1 infection. Previous studies show that colony forming potential of HIV infected progenitor stem cells is reduced, suggesting functional deficiencies can be caused by infection [2, 3]. Hematopoietic stem cells are precursors for several types of mature blood cells. Therefore HIV-1 effects may cause several types of cytopenias due to impairment of stem cell differentiation at the precursor level. Indeed, as described below, patients often suffer from several cytopenias in addition to the T-cell depletion or lymphocytopenia. Another possible cause of the cytopenias observed in HIV infection may involve its direct effects on the mature blood cells.

SCID-hu Mice as a Model of Hematopoiesis in Human Bone Marrow

SCID-hu mice are heterochimeric animals that are constructed by transplanting human fetal thymus (Thy) and liver (Liv) tissues [1, 4] or stem cells [5] into immunodeficient C.B-17 scid/scid (SCID) mice. The phenotype of SCID mice is characterized by the abscence of functional B- and T-lymphocytes [6, 7]. The lack of functional, mature B and T cells in SCID mice results in inability to produce antibodies (Ig levels are usually below 20μg/ml) and consequently the mice do not reject allogeneic grafts [6]. SCID mice have been used for several types of stem cell research, and they are a suitable model for both tissue transplants and HIV-1 infection. SCID mice have been used for studies of cancer stem cells [8] as well as for the studies of HIV-1 infection on human CD34+ stem cells [2, 9].

In addition to being a suitable transplant host, these mice are not productively infected by HIV-1. The transplanted human thymus and liver tissues will form a conjoint organ wherein human hematopoietic CD34+ progenitor stem cells are continuously produced. It takes 4 to 6 months for the new organ to reach a sufficient or an optimal size suitable for various analyses, ex vivo, following its sequential biopsies at different time periods. Our research uses these stem cells as a model of hematopoiesis in human bone marrow to study the indirect effects of HIV-1 infection of the coexisting human thymocytes, on progenitor stem cells in the conjoint hematopoietic organ. Using this in vivo model, it is possible to obtain immature CD34+/CD38lo progenitor cells and study colony formation after differentiation into megakaryoid, erythroid or myeloid progentitor cells. Following HIV-1 infection, colony formation of these undifferentiated early progenitors is inhibited [2, 3], suggesting that the progenitor cells harvested for colony formation assays are at a stage where they respond to hematopoietic growth factor treatment, ex vivo. The results obtained in the SCID-hu model are comparable to those on human bone marrow (Table 1), and there is a significant decrease in colony formation of CD34+ cells derived from both SCID-hu animals and humans. However, since the immune system is operational in the humans but not in the SCID mice, it may explain the higher levels of dysplasia seen in the conjoint human Thy/Liv hematopoietic organ of the SCID-hu mice due to a lack of controlling elements.

Table 1. CD34 positive hematopoietic progenitor cells were isolated from human bone marrow or from SCID-hu Thy/Liv implants and cultured in media designed to induce differentiation of cells in the erythroid (BFU-E), myeloid (CFU-GM) or megakaryocytic (CFU-GMM) lineages. HIV-1 infection reduces the colony forming activity showing that the CD34-positive cells become affected by the infection although they are not actively infected or depleted.

The pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for the decreased proliferative capacity of the bone marrow in AIDS is not well understood. Several studies have suggested that hematopoietic progenitor or stem cells can be directly infected with certain strains of HIV-1 and that viral infection of progenitor cells themselves may ultimately result in impaired hematopoiesis [10, 11]. However, most of these studies have reported in vitro infection of progenitor cells. The SCID-hu mouse, which provides an in vivo system whereby human pluripotent hematopoietic progenitor cells can be maintained, proved to be a better tool for these studies [12]. Using this model, it was shown that HIV-1 infection decreases the recovery of human progenitor cells capable of differentiation into both erythroid and myeloid lineages [9]. Since CD34+ cells are present in the infected implants, the major cause of the reduced colony formation is functional impairment rather than cell depletion. HAART administered after onset of the HIV related impairment transiently reverses the inhibitory effect on colony formation, establishing a causal role of viral replication in the coexisting thymocytes but in an indirect manner.

HIV-1 infection is induced in the SCID-hu mouse by infusion of the virus directly in to the thymus/liver implants. Quantitative DNA PCR for expression of HIV-1 provirus in cells from these implants show active infection [2] Following infection, the mice also have fewer CD4+ cells in the implanted tissue (Table 2). Oral treatment of HIV-1 infected SCID-hu mice with AZT or protease inhibitors reduce the CD4+ T-cell depletion that is typical for HIV-1 infection [14]. HIV-1 protease inhibitors, ritonavir (RTV) and indinavir (IND), have been found to improve hematopoietic function colony formation assays (Table 1) [13, 15, 16].

Table 2. Flowcytometric analysis of white blood cells in healthy humans, and HIV-1 infected humans. Cells from SCID-hu Thy/Liv implants was analyzed using the same staining for a comparison. Data shows that the CD4+ cells in both humans and mice are depleted by the HIV-1 infection.

| Human Subjects (n=20) | SCID-hu mice (n=7) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD3+CD4+ | CD3+CD8+ | CD4/CD8+ | CD3+CD4+ | CD3+CD8+ | CD4+/CD8+ | |

| Healthy/mock treated | 43±6.3a | 25.8±8.1a | 1.67 | 48.9±7.8b | 40.7±8.0b | 1.2 |

| HIV+ | 26.1±8.5a | 54.1±9.8a | 0.48 | 12.8±13.9b | 54±15b | 0.24 |

Data from Costantini et al 2006 [102].

Koka et al unpublished data.

Bone marrow stromal cells, in untreated HIV-1-infected patients, appeared as large and round cells [15]. After HAART, the stromal cells exhibited a normal “fibroblast-like” morphology. This suggests that protease inhibitors may also normalize functional and morphological characteristics of stromal cells. In contrast, in some other studies, stromal cells derived from HIV infected patients and healthy controls have shown the colony forming potential is not dissimilar in studies ex vivo [16], thus raising the specter of proximity of the infected cells such as the thymocytes in circulation to the hematopoietic progenitor cells in the bone marrow as well as the virus loads.

It has been shown that SCID-hu mice [17, 18] have human lymphocytes circulating in their peripheral blood and that these lymphocytes may be evaluated using flow cytometry [18]. This suggests that it may be possible to investigate other mature human blood cells in the mouse blood using antibodies specific for human cells. Humans infected with HIV-1 can be used for studies of the effects of the infection on blood and bone marrow cells. The need for the SCID-mouse model is for the testing of new, not yet FDA approved drugs and experimental studies of the cell biological effects of HIV-1. Blood cells are derived from the stem cells and the two cell types have similar phenotypic features making results derived from the stem cells, at least to some extent, applicable also to the blood cells. Hematopoietic stem cells can be a useful model for drug tests [19, 20], however results from stem cell research needs to be verified by further investigations to elucidate potentially harmful effects of drug dosing on mature blood cells.

Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia consists of many different disorders in which the platelet count is below the normal range of 150,000 and 400,000 platelets per μl of blood in the humans. Thrombocytopenia occurs when platelets are lost from the circulation at a faster rate than new platelets are produced by the bone marrow megakaryocytes. Platelet count varies between individuals, but is fairly constant within a healthy individual over time. Platelets are small blood cells that are very important for blood coagulation, blood clot formation and wound healing. In patients with severe thrombocytopenia, the platelet count can be close to zero, and in mild cases between 100,000 and 150,000 /μl. At a platelet count of 80 to 100,000 /μl there is no imminent risk of severe bleeding. However, in patients having a platelet count less than 30,000 platelets/μL, the risk of severe bleeding is high. HIV-1-related thrombocytopenia is not very common at early stages of the disease [10 % reported by George et al 1996 [21], the incidence is 30-50 % at later stages and in AIDS [22-25]. The degree of HIV-related thrombocytopenia is generally mild to moderate; however, severe reduction of platelet count below 50,000/μl also occurs [26, 27].

Platelets have an important function for this process called primary hemostasis (Figure 4). Inside each platelet there are granules, containing compounds that enhance the ability of platelets to stop bleeding by sticking to each other, to the surface of a damaged blood vessel wall, or at skin lacerations. The coagulation factors are then activated resulting in the cleavage of fibrinogen to fibrin, which together with the platelets form an insoluble clot.

Figure 4.

Platelets contribute to blood clotting by adhering to other platelets, and by secreting substances that activates plasma protein. A blood clot consists of platelets in a fibrin mesh net. The fibrin mesh can be dissolved by the process of fibrinolysis prior the maturation. Thrombocytopenia increases the risk for bleeding.

There is as described above not a close relationship between the platelet count and the risk or the severity of bleeding. Both low platelet counts and impaired platelet function (for example by aspirin) constitutes a risk of bleeding. The first spontaneous bleeding is usually seen on the skin in the form of petechiae, bruising, or bleeding from the nose and the gums. More serious complications include, intracranial or gastrointestinal bleeding. Petechiae is a sign of thrombocytopenia and as such included in the routine physical examination of healthy individuals and in examination of HIV-1 infected patients.

Mature megakaryocytes release platelets to the blood and their production is regulated by blood level of thrombopoietin (TPO). When the TPO levels increase, greater numbers of CD34+ progenitor stem cells differentiate in the megakaryocytic lineage causing increased platelet production. When platelet counts increase, TPO clearance from circulation is higher due to binding to the TPO receptors (c-Mpl) on the platelets, and fewer platelets will be produced by the bone marrow. Under physiological conditions this loop controls the peripheral platelet counts. Average life span of a blood platelet in a healthy person is 10 days. Efforts have been made to develop clinically useful methods to distinguish between thrombocytopenias that are caused by inefficient platelet production versus increased platelet destruction [28, 29]. However these methods are still labor intensive and more convenient methods are commercially available for the routine clinical laboratory setting. Anti-platelet antibodies can be detected by specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) which detects only glycoprotein-specific platelet antibodies (GP IIb/IIIa, GP Ib/IX, GP Ia/IIa) that are associated with immune thrombocytopenia.

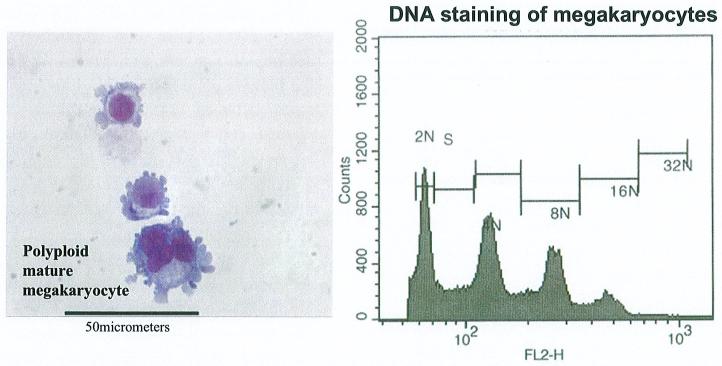

Increases in TPO level generally promotes preferential differentiation of CD34+CD38- stem cells into megakaryocytic lineage [30], differentiation progresses with a subsequent decrease in CD34 expression and increase in CD41 and CD61 expression [31, 32]. Mature megakaryocytes, i.e., cells with a ploidy of 16 N or more, produce platelets (Figure 5). Megakaryocyte expansion of hematopoietic progenitor cells in thrombopoietin (TPO)-depleted animals was reduced as much as 10 to 20-fold [33, 34]. There is no proof of reduced TPO levels in HIV infection in humans. TPO levels have instead shown to be higher [26]. But this is not necessarily a correlation with TPO gene expression (neither with the progenitor cells) and may be the result of lack of availability of sufficient numbers of c-Mpl molecules on platelet surface for TPO binding, due to persistent cycle of internalization of TPO-c-Mpl complexes as a result of surplus TPO in the cellular environment. Platelets from HIV-1 positive patients express more TPO (c-Mpl) receptors than platelets from healthy individuals but the levels of c-Mpl receptors in the blood is the same between healthy and infected individuals [35].

Figure 5.

Megakaryocytes are bone marrow cells that produce platelets. Megakaryocytes do not divide as their DNA content increase. Megakaryocytes with a ploidy over 16N can produce platelets.

HIV-1 can infect megakaryocytes, which means that the virus itself can directly cause thrombocytopenia at this level that leads to platelet formation. HIV-1 infected megakaryocytes that are mature, 16N-128N [26], may not efficiently produce platelets. Megakaryocytes are potentially susceptible to HIV infection through the viral CXCR4 coreceptor [36-38] even in the absence of its primary receptor, CD4 [39-41]. Other cell surface markers like Fyn and Lyn kinase have been suggested as a target for HIV-1 action. Recently it was shown that Lyn and Fyn kinase is a regulator of TPO induced cell signaling [31, 42]. Microarray and Western blot analysis demonstrate that Fyn, Lyn, Fgr, Hck, Src, and Yes are all expressed in cultured human megakaryocytes. However, only Fyn and Lyn are further activated by TPO stimulation, but that response seems specific for the proliferative stage. On mature megakaryocytes, Fyn expression remains upregulated while Lyn is downregulated, suggesting differential gene regulation. Nef is a protein expressed by HIV-1 genome and is required for viral replication. Nef interacts with several signaling molecules including members of the Src-family of tyrosine kinases, including Lyn and Fyn [43]. A Nef-Lyn interaction in vivo could partially replace the Nef-Hck interaction that has been shown to be one possible pathway for AIDS progression [44]. Lyn has been reported to bind to Nef in vitro [43]. It has been shown that Nef induces Hck kinase activation and fibroblast transformation [45] but Nef has no effect on Lyn activity and suppresses the activity of Fyn. Since the activity of Fyn and Lyn during megakaryopoiesis varies with the phase of the cell cycle, it is still unclear whether Nef can affect megakaryopoiesis. Nef also may be causing thrombocytopenia since it is a region towards which antibodies have been shown to be formed [46] suggesting a mechanism for molecular mimicry with Fyn and Lyn, in HIV-1 induced thrombocytopenia.

Impaired platelet production may be due to the toxic side effects of drugs such as chemotherapy (anti-cancer) agents, alcohol, HIV-1 and other viral infections, and/or drugs used to treat HIV-1 related diseases or myelodysplasia. Abnormality of the structural parts of the marrow (stroma) may also cause low platelet production by affecting the milieu in the bone marrow. Within the bone marrow microenvironment, stromal cells can influence such fundamental processes as survival, proliferation, and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells. The contact of megakaryocytes with stromal cells has been shown to be of crucial importance for stem cell differentiation using different in vitro culture systems in which stromal contact supports multipotent progenitors [47], including B-cell progenitors [48]. Stromal cells influence hematopoiesis by secretion of soluble cofactors, production of extracellular matrix, and direct receptor-counter receptor engagements [49]. Deficiencies of the stromal cells can block hematopoietic differentiation [50]. Data from infected SCID-hu mice shows that the IL-6 RNA expression is upregulated while stromal cell-derived factor (SDF-1) is not affected [51]. It is also known from in vitro experiments of mesenchymal stem cells incubated with SDF-1, that SDF-1 exposure can cause the production of factors (including IL-6) that may inhibit stem cell differentiation [52]. Factors that inhibit c-Mpl expression could inhibit multilineage hematopoiesis [2]. Megakaryocytic differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells grown in medium with desulfated stroma was decreased to 50 % of the megakaryocytic differentiation in medium with sulfated stroma [54]. Indeed, proteoglycans in bone marrow and in particular heparan sulfate proteoglycans, are involved in binding hematopoietic progenitor cells and cytokines that inhibit megakaryocytopoiesis. Bone marrow stromal proteoglycans thus reduce differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells toward megakaryocytes.

It has been reported that the bone marrow fails to increase megakaryopoiesis in HIV-1 infected patients if their platelet count drops [55] suggesting that the virus inhibits earlier of stages differentiation of progenitor cells into megakaryocyte lineage cells. In a case-control study of 50 HIV-positive patients with thrombocytopenia (<150,000 cells/mm3), it was found that in patients with thrombocytopenia, this condition is related to lower CD4 cell counts (mean 161 vs. 414 cells/ul), higher CD8 T-cell percentages (59 vs. 47%) and higher viral loads (249,000 vs. 74,600 copies/ml) than HIV-positive, gender-, age- and treatment-matched controls [56]. Thrombocytopenic patients on HAART had higher viral loads (24,800 vs. 6520 copies/ml) and lower CD4 cell counts (239 vs 447 cells/ul) than HIV-positive patients who were administered HAART.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) occurs when lymphocytes produce antibodies against platelets. The name ITP is related to any specific antibody and can therefore be linked to numerous pathological conditions. It has been shown that the mean platelet life span and turnover of autologous Indium-111-labeled platelets is short in HIV-infection [57]. This study clearly shows that anti-platelet antibodies rapidly destroy the platelets which are in circulation. Seven thrombocytopenic patients had a very short platelet life span (3.0+/-3.8 h) in spite of a marked increase in platelet production (18.2+/-12.6×10(9)/l/h). Only 5 of 10 patients with a normal blood platelet count had a shortened platelet life span (109+/-23 h) and increased platelet turnover (3.8+/-1.2×10(9)/l/h), meaning that the increased peripheral platelet destruction could be compensated for by increased platelet production. The other five patients with a normal platelet count had normal platelet life span (195+/-11 h) and slightly increased platelet production (2.5+/-0.6×10(9)/l/h). In patients with HIV-associated thrombocytopenia, the increased peripheral platelet destruction is sufficiently large that even if platelet production is elevated it is insufficient to compensate for their rapid destruction. Anti-platelet antibodies and circulating immune complexes cause peripheral destruction in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow, in that order [58, 59].

Platelet numbers fall as antibody coated cells are removed from the circulation more rapidly than new platelets can be produced. Platelets coated with an antibody are then removed, or if not removed they will be used up by a condition in which the blood clotting process is inappropriately ‘switched on’ called disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). As mentioned above, in early HIV-1 infection, autoimmune thrombocytopenia occurs when an antibody is developed and directed against an immunodominant epitope, for example, the GPIIIa integrin (GPIIIa49-66). This antibody induces thrombocytopenia by a novel mechanism in which platelets are fragmented by antibody-induced generation of hydrogen peroxide derived from the interaction of platelet nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and 12-lipooxygenase. The GPIIIa integrin is present on both platelets and megakaryocytes. Platelets-antibody complexes are being destroyed in the spleen but the faith of megakaryocyte-antibody complexes is not well known. It is however likely that megakaryocyte-antibody complexes are not functional units. Further investigation of the properties of the antibody binding sites revealed that there was molecular mimicry between these sites and polymorphic regions of HIV-1 proteins. A known epitope of nef is particularly incriminated. It has been shown that molecular mimicry of nef, an HIV-1 encoded protein region, can cause platelet lysis in vitro [46].

Another study supports increased platelet destruction as a cause of thrombocytopenia. Platelet survival time in 24 men with HIV-related thrombocytopenia (16 who received no treatment and 8 who received zidovudine), 20 HIV-infected men with normal platelet counts (10 who received no treatment and 10 who received zidovudine), and 12 healthy controls, were compared [59]. Platelet survival was decreased in both the untreated and the zidovudine treated patients with HIV-related thrombocytopenia (to 92 ± 33 and 129 +/- 44 h) as compared with the normal controls (198 +/- 15 h). Mean platelet survival was also significantly decreased in the HIV-infected patients with normal platelet counts (untreated, 162 ± 23 h; zidovudine treated, 166 ± 35 h). Increased platelet production can compensate for rapid loss and reduced platelet production can cause thrombocytopenia. HIV-1 positive patients with thrombocytopenia have reduced platelet production (23,000 ± 11,000 platelets/μl/d) as compared with the healthy controls (45,000 ± 6,000 platelets/μl/d). Mean platelet production was increased, however, with zidovudine treatment, both in HIV infected patients with thrombocytopenia (60,000 ± 31,000 platelets/μl/d) and without thrombocytopenia (68,000 ± 22,000 platelets/μl/d). Increased platelet production [60] was observed in 9 of 10 patients on HAART and they responded to this treatment with durable improvement in hematologic, virologic, and immunologic responses were achieved. The median follow-up was 30 months (range 21-46) with no thrombocytopenic relapses suggesting that HAART may have the dual benefit of improving platelet counts and the regression of HIV infection.

Noticeable levels of inhibition of apoptosis in peripheral blood mononuclear cells have been observed in HAART treated patients [61]. Levels of cell apoptosis were higher in CD8+ T-cells than in CD4+ T-cells. Indeed CD4+ cell counts correlated inversely with levels of CD8+ apoptotic cells, but were unrelated to levels of apoptosis of CD4+ T-cells. This indicates that the increase of CD4+ lymphocytes in patients that received HAART, may be attributed to a relative increase in apoptosis in the CD8+ T-cells. Since there is no apparent reduction of apoptosis of cells in the CD4+T-cell compartment, the cell life span might be prolonged. In addition HAART treatment returns CD34+ cell colony formation from HIV-1 positive donors to the levels of uninfected donors (Table 1)

HAART should be considered to be a life-long treatment since HIV-1 plasma viral load rebounds from viral reservoirs if treatment is interrupted. Several cytokines with γ-chain homology, including IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15, could aid the depletion of viral reservoirs. IL-7 stimulates thymopoiesis, and systemic administration of recombinant IL-7 to murine bone marrow transplant recipients improves immune function after the transplant [62-64]. Furthermore, endogenous IL-7 may increase in response to T lymphopenia [65] such as in HIV-1 infection. The cell activation and differentiation play a critical role in the ability of HIV-1 to achieve and maintain active replication [66]. Cytokine-treatment alters the activation state of the host cell and thus alters patterns of viral infection and replication [67, 68], and this could provide an optional therapy to both activate the reservoir of latently infected T cells and to improve immune function in AIDS patients. IL-2 is the best characterized cytokine [69 - 71] and in combination with HAART produces significant CD4+ T lymphocyte expansion without an increase in viral load [72-75]. The elevated IL-7 levels in HIV-1 infection [65, 76] indicated that IL-7 increases mature lymphocyte counts. IL-7/HAART combination may become a valuable treatment option, and some positive results are available [77]. Further study of the mechanism of combination therapies, and their potential effect on viral reservoirs, will contribute to valuable knowledge for clinical therapies. In implants of HIV-1 infected SCID-hu mice treated with IL-2, IL-4, or IL-7 there was a delayed depletion of immature thymocytes [68]. IL-2 maintained immature thymocytes. IL-4 and IL-7 causes an increased viral load, which IL-2 do not. HAART may have prevented the more rapid increase in viral loads caused by the cytokines since free virus would have been cleared from the blood. If HAART is not sufficient to treat the thrombocytopenia condition, a number of other treatments are available, and these treatments may not be directed towards the HIV infection. Prednisone, intravenous gamma-globulin, splenectomy, and antiretroviral monotherapy with zidovudine, can be used to treat HIV-related thrombocytopenia in adults and children.

AZT can rapidly increase platelet counts in patients with HIV-related thrombocytopenia [78, 79]. This effect is attributed to the decreased virus levels in the blood, and the decreased amount of anti-platelet antibodies while on HAART. In patients that respond to HAART, the increase generally occurs within several weeks of initiating treatment, and is not sustained after cessation of the treatment. In a longitudinal study of 92 HIV-infected thrombocytopenic patients on HAART [80], it was shown that 50% had viral loads below 500 copies/ml blood after 2 years of treatment and improvement from the condition of thrombocytopenia. Mean platelet count rose from 110,000 to 180,000 at 6 months after initiation of HAART. Other investigators [56] have reported that low platelets persisted in 70% of the patients receiving HAART for at least 2 years. This suggests that other factors contribute to the risk of thrombocytopenia. These factors seem to play a role as in studies of HIV-1 positive drug users wherein the risk of thrombocytopenia was associated with use of heroin and they also exhibited low selenium and abnormal liver enzyme levels [81]. It was concluded that several factors predict thrombocytopenia and that thrombocytopenia may be associated with more rapid HIV disease progression in drug users, despite antiretroviral therapy, by comparing 26 HIV-infected drug users with thrombocytopenia and 54 age-matched HIV-infected control individuals.

A retrospective study of 15 HAART treated HIV-1 positive patients with severe thrombocytopenia showed that platelet count normalize with treatment [82]. Also treatment with IV gamma globulin [83] increases median platelet counts significantly from 17,000 to 220,000. However, the effect was transient, and the median platelet counts declined to 40,000 after treatment. It has also been shown that interferon alpha treatment increases platelet counts [84, 85]. Other drugs and treatments that have positive effects on HIV-related thrombocytopenia are Dapsone, oral steroids, splenectomy, and intravenous vincristine. Non-surgical methods for treating thrombocytopenia is preferable to the traditional splenectomy since surgery in patients at risk for bleeding is always a complication, and should be performed when other options are a failure.

Anemia and/or HIV-1 Infection of Red Blood Cells

The incidence of anemia is high in HIV infected patients, but they are often undiagnosed and untreated because it seems like an insignificant problem in the many complications that happen in HIV disease. In general, in HIV disease, 30% of the infected individuals are anemic, and over 50% of people with AIDS are anemic [86]. In different studies, the prevalence of anemia in persons with AIDS has been shown to be as high as 63% to 95% thus making it more common than thrombocytopenia or leukopenia in these patients with AIDS. HIV infection may lead to anemia in many ways: changes in cytokine production with subsequent effects on hematopoiesis, decreased erythropoietin concentrations, opportunistic infectious agents such as Mycobacterium avium complex or parvovirus B-19, and administration of chemotherapeutic agents such as zidovudine or ganciclovir. Less common mechanisms for HIV-associated anemia include vitamin B12 deficiency and autoimmune destruction of red blood cells.

Normal production of red blood cells in the bone marrow requires adequate amounts of nutrients like iron, the vitamins B12 and folic acid for the production of mature red blood cells, sufficient production of erythropoietin (EPO) that stimulate red blood cell development, and the presence of immature bone marrow cells that can develop into mature cells. Inadequate EPO production may also contribute to anemia, whereas in healthy individuals the body replaces RBC by producing more EPO to stimulate replacement of the lost blood cells from bone marrow erythroblasts. Studies of hematopoietic progenitor stem cells from HIV-1 infected SCID-hu mice shows that there is a reduction of colony forming activity (CFA) in CD34+ progenitor cells differentiating into the erythroid lineage (Table 1), [2, 3]. In people with chronic diseases, including HIV, the amount of EPO produced by the kidneys may not be enough to stimulate normal red blood cell production. HIV-infected people with normal kidneys, with kidney damage from HIV itself, or on HAART medications can all have reduced EPO production. Also, the response to EPO by the bone marrow is less than normal in people with HIV infection. In HIV-1-infected patients suffering from anemia, circulating antibodies to endogenous erythropoietin was found in 48 of the 204 patients that were studied [87]. EPO stimulates differentiation of CD34+ cells into the erythroid lineage. HIV effects on EPO could be suggestive of reduced RBC production from the stem cells. Many drugs used to treat HIV infection or its complications also have toxic side effects on erythroid progenitor cells that can lead to anemia. The likelihood of developing anemia when these drugs are used increases as immune function becomes progressively impaired. Among the drugs commonly associated with anemia are Retrovir® (AZT), TMP-SMX (Bactrim™, Septra®), ganciclovir, dapsone, pyrimethamine, interferon, and cancer chemotherapy. Most often, in HIV disease, anemia is caused by antiretroviral drugs that are used to treat infections, or in cancer, the chemotherapeutic agents [88]. To discontinue HAART would pose a threat to HIV positive patients and therefore treating the anemia itself may be a more favorable alternative.

In over 95 % of HIV infected patients the virus is bound to their RBCs and this may have been caused by virus infection of the mature blood cell. This pool of virus represents a very large reservoir because the level of RBCs in circulation is high, and RBC bound HIV can be infectious [89]. There are 3,600 to 6,100 RBCs in one ul of blood. In patients with undetectable plasma virus levels there may be detectable levels of HIV-1 provirus in the erythrocytes (1 copy/μl blood) [90]. This would mean that an HIV-1 infected patient on HAART and with undetectable levels of virus in the plasma is still suffering from an active infection and virus is being produced from the presumably infected RBCs. As the infected RBCs circulate in the blood vessels they may also infect other cells like platelets, white blood cells, and dendritic cells [91 - 95]. A majority of HIV-1 infected patients have RBC-associated HIV-1 (80 of 82) [90]. High level of RBC-associated HIV was related to more advanced clinical stage of infection suggesting that the bound HIV may contribute to anemia. In clinical treatments, it could prove valuble to measure the amount of RBC-associated HIV, to adjust the HAART to the individual needs of the patient. Immediately following infection, most patients start producing specific antibodies, and these antibodies form complexes with HIV-1. Both these complexes and free HIV-1 virus can bind to RBCs [96, 97]. Complement proteins attach to the RBC-associated HIV complexes, and an inverse relationship between CD35 on RBC and HIV in plasma suggests that these complexes target the CD35 antigen on RBCs [90].

To study, the factors associated with, and the prevalence of anemia in HIV-infected persons, data was obtained from medical records of 32,867 HIV-infected persons who received care from 1990 through 1996 in 9 US cities [98]. The incidence of anemia was 3.2% for HIV infected persons, 12.1% for patients with low CD4 count but not clinical AIDS and 36.9% for persons with clinical AIDS. It was estimated that 22% were related to zidovudine, fluconazole, and ganciclovir, or lack of prescription of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The increased risk of death was greater for those who developed anemia, specially if the anemia did not resolve. It is however not known if recovery from anemia is associated with improved survival. Anemia is a treatable condition in HIV infection and it is important if there is a causal relationship between recovery from anemia and survival time. Treatments for anemia during longer periods with drugs like recombinant human erythropoietin (r-huEPO) are complicated and only suitable for patients with anemia caused by low RBC levels. Seventy two percent of men and 69% of women with HIV-1 infection, had hemoglobin concentrations within the reference range (above 14 or 12 g/dL, respectively). Most patients with clinical AIDS, 87 % of the men and 77 % of the women, had hemoglobin concentrations below the reference range. Anemia, whether drug-related or unrelated to drugs, was strongly associated with clinical AIDS, low CD4 T-cell count, bacterial septicemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and prescription of ganciclovir, ZDV, and fluconazole, and negatively associated with the prescription of TMP-SMX. Mortality analyses were not different for persons recovering from drug-related anemia or anemia unrelated to drugs. This association is most likely explained by the increasing viral burden as HIV disease not treated with HAART progresses, which could cause anemia by increased cytokine-mediated myelosuppression. Both prescription of ZDV and ganciclovir cause myelosuppression and hence increase the risk of anemia. The data showing a relationship between drug intake and anemia is dependent on that the drug is recognized or recorded in medical records as a possible cause of anemia.

Neutropenia

Neutropenia is a shortage of neutrophils. These are a type of white blood cells that mainly attack bacteria and fungi, and so neutropenia increases the risk of infections. Neutropenia is generally defined as absolute neutrophil count (ANC) < 1,000/ul. In patients with HIV infection, neutropenia can result from directly or indirectly impairing hematopoiesis. In the SCID-hu model CD34+ stem cells from HIV-1 infected mice have reduced CFA of the progenitor cells inducing their differentiation into the myeloid lineage (Table 1). Other microorganisms that cause opportunistic infections, such as cytomegalovirus and Mycobacterium avium complex, can infiltrate the bone marrow and cause myelo-suppression. Hematologic toxicities of drug therapy targeted against HIV and opportunistic infections, such as zidovudine, cidofovir, foscarnet, ganciclovir, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, can all further reduce blood cell formation (Table 3).

Table 3. Medications commonly used in the treatment of HIV-1 positive patients and their relationship to cytopenias.

| Drug | Thrombocytopenia | Anemia | Neutropenia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abacavir (Ziagen)3 [103] | yes | ||

| Acyclovir [104] | yes | yes | |

| Amphotericin B1 [105] | yes | yes | |

| Cidofovir | yes | yes | |

| Dapsone1 [106, 107] | yes | ||

| Epivir (3TC)2 | yes | ||

| Fluconazole | yes | ||

| 5-Flucytosine1 | yes | yes | yes |

| Foscarnet | yes | yes | |

| Ganciclovir1 [98] | yes | yes | yes |

| Hivid (ddC)2 | yes | yes | |

| Indinavir(Crixivan)3[98] | yes | ||

| Ketoconazole | yes | ||

| Pentamidine [111] | yes | yes | |

| Primaquine1 [106] | yes | ||

| Pyrazinamide | yes | ||

| Pyrimethamine1 | yes | yes | yes |

| Retrovir (AZT)2[98] | yes | yes | yes |

| Rifabutin | yes | ||

| Rifampin [110] | yes | ||

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole [106] | yes | yes | yes |

| Trimetrexate1 [109] | yes | yes | |

| Valganciclovir [108] | yes | ||

| Videx (d4T)3 | yes | ||

| Zidovudine2 [107] | yes | yes |

Therapy for opportunistic infections

Antiviral agents

Protease inhibitors. See also Physicians Desk Reference for information on contraindications and adverse effects

The commonest cause of neutropenia is the result of drugs such as AZT, the anti-CMV drug ganciclovir, or drugs used to treat cancers and tumors. HIV-1 positive patients often have slightly lower levels of neutrophils than uninfected people, but serious neutropenia is rare among HIV-1 positive patients with CD4+ cell counts above 200. Neutropenia can be treated by reducing the dose or stopping the drug which is causing this condition. Alternatively, if the neutrophil count falls very low (below 500) treatment with G-CSF to stimulate the bone marrow production of white blood cells may reduce neutropenia and thus indirectly, the risk of infections. It is worth to note that the bone marrow in HIV-1 positive patients respond to cytokine treatments of TPO, EPO, and G-CSF, and will increase the progenitor cell differentiation into the respective lineages.

Serum levels of the endogenous granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) in HIV-seropositive individuals with neutropenia or acute febrile infection were found to be normal [99]. HIV-infected patients (n= 28) with neutropenia (<1000 cells/ul) had low G-CSF serum levels (i.e., median was below the detection limit for the ELISA method that was used) not different from those of healthy volunteers (n = 66), or of non-neutropenic HIV-infected control individuals (n= 75). Patients with acute myeloid leukemia and afebrile neutropenia from chemotherapy (n = 17) demonstrated markedly elevated G-CSF levels (264 pg/ml). Only HIV-infected patients with pneumonia (n = 17) had increased G-CSF serum levels (152 pg/ml) and the levels were similar to G-CSF values in HIV-negative patients (n = 17) with pneumonia (123 pg/ml). HIV-infected patients respond differently to episodes of neutropenia or acute febrile inflammation. This suggests different mechanisms for the regulation of G-CSF and the low levels of G-CSF may contribute to the neutropenia.

Several retrospective studies are reviewed that examined the relationship between ANC and the development of bacterial infections in HIV-1 positive patients. Approaches to shorten or prevent neutropenia will most likely provide substantial clinical benefit, although neutropenia in the presence of HIV infection is rarely severe and is not usually associated with increased infection [100]. Adult HIV-infected patients with absolute neutrophil counts of <1000 cells/mL usually recover within a month even if HAART is continued. From 17,000 inpatient and outpatient visits, 87 patients with new neutropenic episodes were identified. For those who presented with neutropenia, the mean CD4+ T-cell cell count at the first episode was as low as 153 cells/mL, and at the second and subsequent episodes CD4+ T-cell count was 103 cells/mL. Moore et al [100] also report that neutropenia occur at a low CD4+ T-cell count (30 cells/ul) and the lower the CD4+ T-cell counts the longer the duration of neutropenia. In the 87 patients with ANC, four serious and eight moderate infections developed. Two of the serious infections occurred in subjects with a neutrophil count below 200 cells/mL blood. Lower mean CD4+ T-cell counts were common among the patients that developed infections than those without infections, 64 vs 126 cells/mL. The CD4+ T-cells level per se was so low that it is not clear whether it represents any clinically relevant difference. In general, low levels of one cell type seem to correlate to other cytopenias and any successful treatment seems to improve all cytopenias.

HIV-infected patients with a PMN count of < 1000/ul confirmed on two occasions were studied for cause of the neutropenia. These patients were on HAART with zidovudine in 32 (51%), trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) in 28 (45%) and ganciclovir in 11 (18%) patients, and compared to those receiving chemotherapy of 7 (11.3%) patients. Fifteen patients (24%) developed infection related complications. Neutropenia may have been induced by zidovudine, gangiclovir or TMP-SMX, anti-HIV drugs, but these episodes were frequently complicated by episodes of infection than neutropenia that was induced by chemotherapy [101].

Conclusions

HIV-1 infection is a disease that poses a risk for several cytopenias, this may be caused by the effects of the virus on bone marrow hematopoietic progenitor cells or direct effects of the virus on mature blood cells. Human hematopoietic progenitor stem cells from thymus/liver implants derived from SCID-hu mice can be used in studies of the effects of HIV-1 infection with results showing good agreement with those obtained from human patients. The model can be used for experimental studies with significant time duration. SCID-hu mouse is therefore an experimental model system that can be used both in studies of the mechanisms of HIV-1 infection and for initial testing of potential therapies for cytopenias.

Acknowledgements

P.S.K is a recipient of a grant from the NHLBI/NIH (5RO1HL079846).

References

- [1].Rabin L, Hincenbergs M, Moreno MB, Warren S, Linquist V, Datema R, Charpiot B, Seifert J, Kaneshima H, McCune JM. Use of standardized SCID-hu Thy/Liv mouse model for preclinical efficacy testing of antihuman immunodeficiency virus type 1 compounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996 Mar;40(3):755–62. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Koka PS, Kitchen CM, Reddy ST. Targeting c-Mpl for revival of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-induced hematopoietic inhibition when CD34+ progenitor cells are re-engrafted into a fresh stromal microenvironment in vivo. J. Virol. 2004 Oct;78(20):11385–92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11385-11392.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Koka PS, Jamieson BD, Brooks DG, Zack JA. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-induced hematopoietic inhibition is independent of productive infection of progenitor cells in vivo. J. Virol. 1999 Nov;73(11):9089–97. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9089-9097.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Aldrovandi GM, Feuer G, Gao L, Jamieson B, Kristeva M, Chen IS, Zack JA. The SCID-hu mouse as a model for HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1993;363(6431):732–6. doi: 10.1038/363732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Watanabe S, Terashima K, Ohta S, Horibata S, Yajima M, Shiozawa Y, Dewan MZ, Yu Z, Ito M, Morio T, Shimizu N, Honda M, Yamamoto N. Hematopoietic stem cell-engrafted NOD/SCID/IL2R{gamma} null mice develop human lymphoid system and induced long-lasting HIV-1 infection with specific humoral immune responses. Blood. 2006 Sep 5; doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017681. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bosma GC, Custer RP, Bosma MJ. Nature. 1983;301:527–530. doi: 10.1038/301527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Habu S, Kimura M, Katsuki M, Hioki K, Nomura T. Eur. J. Immunol. 1987;17:1467–1471. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Al-Hajj M, Becker MW, Wicha M, Weissman I, Clarke MF. Therapeutic implications of cancer stem cells. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development. 2004;14(1):43–4. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Koka PS, Fraser JK, Bryson Y, Bristol GC, Aldrovandi GM, Daar ES, Zack JA. Human immunodeficiency virus inhibits multilineage hematopoiesis in vivo. Journal of Virology. 1998;72(6):5121–27. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5121-5127.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Geissler RG, Ganser A, Ottmann OG, Gute P, Morawetz A, Guba P, Helm EB, Hoelzer D. In vitro improvement of bone marrow-derived hematopoietic colony formation in HIV-positive patients by alpha-D-tocopherol and erythropoietin. Eur. J. Haematol. 1994 Oct;53(4):201–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1994.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Geissler RG, Ottmann OG, Kleiner K, Mentzel U, Bickelhaupt A, Hoelzer D, Ganser A. Decreased haematopoietic colony growth in long-term bone marrow cultures of HIV-positive patients. Res. Virol. 1993 Jan-Feb;144(1):69–73. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(06)80014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Koka PS, Reddy ST. Cytopenias in HIV infection: mechanisms and alleviation of hematopoietic inhibition. Curr. HIV Res. 2004 Jul;2(3):275–82. doi: 10.2174/1570162043351282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Withers-Ward ES, Amado RG, Koka PS, Jamieson BD, Kaplan AH, Chen IS, Zack JA. Transient renewal of thymopoiesis in HIV-infected human thymic implants following antiviral therapy. Nat. Med. 1997 Oct;3(10):1102–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1097-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Miles SA, Lee K, Hutlin L, Zsebo KM, Mitsuyasu RT. Potential use of human stem cell factor as adjunctive therapy for human immunodeficiency virus-related cytopenias. Blood. 1991 Dec 15;78(12):3200–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Isgrò A, De Vita L, Mezzaroma I, Aiuti A, Aiuti F. Recovery of haematopoietic abnormalities in HIV-1 infected patients treated with HAART. AIDS. 1999;13(17):2486. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199912030-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sloand EM, Young NS, Sato T, Kumar P, Kim S, Weichold FF, Maciejewski JP. Secondary colony formation after long-term bone marrow culture using peripheral blood and bone marrow of HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1997 Nov;11(13):1547–53. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199713000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Plum J, De Smedt M, Verhasselt B, Kerre T, Vanhecke D, Vandekerckhove B, Leclercq G. Human T lymphopoiesis. In vitro and in vivo study models. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2000;917:724–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Krowka JF, Sarin S, Namikawa R, McCune JM, Kaneshima H. Human T cells in the SCID-hu mouse are phenotypically normal and functionally competent. J. Immunol. 1991;146(11):3751–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dal Negro G, Vandin L, Bonato M, Repeto P, Sciuscio D. A new experimental protocol as an alternative to the colony-forming unit-granulocyte/macrophage (CFU-GM) clonogenic assay to assess the haematotoxic potential of new drugs. Toxicol In Vitro. 2006 Aug;20(5):750–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sartipy P, Bjorquist P, Strehl R, Hyllner J. Pluripotent human stem cells as novel tools in drug discovery and toxicity testing. IDrugs. 2006 Oct;9(10):702–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].George JN, Ballem PJ, Burstein SA, American Society of Hematology Hemostasis/platelets. Haematology, Education Program. 1996;3:75–81. section. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Murphy MF, Metcalfe P, Waters AH, Carne CA, Weller IV, Linch DC, Smith A. Incidence and mechanism of neutropenia and thrombocytopenia in patients with HIV infection. Br. J. Haem. 1987;66:337–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1987.tb06920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rossi G, Gloria R, Stellini R, Franceschini F, Bettinzioli M, Cadeo G, Sueri L, Cattaneo R, Marinone G. Prevalence, clinical and laboratory features of thrombocyopenia among HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 1990;6:261–269. doi: 10.1089/aid.1990.6.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Scadden DT, Zon LI, Groopman JE. Pathophysiology and management of HIV associated hematologic disorders. Blood. 1989;74:1455–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sioand EM, Klein HG, Banks SM, Vareldziz B, Merritt S, Pierce P. Epidemiology of thrombocytopenia in HIV infection. European Journal of Haematology. 1992;48:168–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1992.tb00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cole JL, Marzec UM, Gunthel CJ, Karpatkin S, Worford L, Sundell IB, Lennox JL, Nichol JL, Harker LA. Inneffective platelet production in thrombocytopenic human immunodeficency virus-infected patients. Blood. 1998;91(9):3239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lima J, Ribera A, Garcia-Bragado E, Monteagudo M, Martin-Vega C, Bastida MT. Antiplatelet antibodies at primary infection by HIV. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1987;106:333. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-2-333_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Savage B, McFadden PR, Hanson SR, Harker LA. The relation of platelet density to platelet age: survival of low- and high-density 111indium-labeled platelets in baboons. Blood. 1986;68(2):386–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tomer A, Hanson SR, Harker LA. Autologous platelet kinetics in patients with severe thrombocytopenia: discrimination between disorders of production and destruction. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1991;118(6):546–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ramsfjell V, Borge OJ, Cui L, Jacobsen SE. Thrombopoietin directly and potently stimulates multilineage growth and progenitor cell expansion from primitive (CD34+ CD38-) human bone marrow progenitor cells: distinct and key interactions with the ligands for c-kit and flt3, and inhibitory effects of TGF-beta and TNF-alpha. J. Immunol. 1997;158(11):5169–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lannutti BJ, Shim MH, Blake N, Reems JA, Drachman JG. Identification and activation of Src family kinases in primary megakaryocytes. Exp Hematol. 2003;31(12):1268–74. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shim MH, Hoover A, Blake N, Drachman JG, Reems JA. Gene expression profile of primary human CD34+CD38lo cells differentiating along the megakaryocyte lineage. Experimental Hematology. 2004;32:638–648. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fox N, Priestley G, Papayannopoulou T, Kaushansky K. Thrombopoietin expands hematopoietic stem cells after transplantation. J. Clin. Investig. 2002;110:389–394. doi: 10.1172/JCI15430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kimura S, Roberts AW, Metcalf D, Alexander WS. Hematopoietic stem cell deficiencies in mice lacking c-Mpl, the receptor for thrombopoietin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1195–1200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sundell IB, Koka PS. Thrombocytopenia in HIV infection: impairment of platelet formation and loss correlates with increased c-Mpl and ligand thrombopoietin expression. Curr. HIV Res. 2006 Jan;4(1):107–16. doi: 10.2174/157016206775197646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Michael NL, Nelson JAE, KewalRamani VN, Chang G, O’Brien SJ, Mascola JR, Volsky B, Louder M, White GC, II, Littman DR, Swanstrom R, O’Brien TR. Exclusive and persistent use of the entry coreceptor CXCR4 by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from a subject homozygous for CCR5 D32. Journal of Virology. 1998;72:6040–6047. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6040-6047.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Oberlin E, Amara A, Bachelerie F, Bessia C, Virelizier J-L, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Schwartz O, Heard J-M, Clark-Lewis I, Legier DF, Loetscher M, Baggiolini M, Moser B. The CXC chemokine SDF-1 is the ligand for LESTER/fusin and prevents infection by T-cell-line-adapted HIV-1. Nature. 1996;382:833–835. doi: 10.1038/382833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Riviere C, Subra F, Cohen-Solal K, Cordette-Lagarde V, Letestu R, Auclair C, Vainchenker W, Louache F. Phenotypic and functional evidence for the expression of CXCR4 receptor during megakaryocytopoiesis. Blood. 1999;93(5):1511–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Dalgleish AG, Beverley PC, Clapham PR, Crawford DH, Greaves MF, Weiss RA. The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature. 1984;312:763–767. doi: 10.1038/312763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Klatzmann D, Champagne E, Chamaret S, Gruest J, Guetard D, Hercend T, Gluckman JC, Montagnier L. T-lymphocyte T4 molecule behaves as the receptor for human retrovirus LAV. Nature. 1984;312:767–768. doi: 10.1038/312767a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Maddon PJ, Dalgleish AG, McDougal JS, Clapham PR, Weiss RA, Axel R. The T4 gene encodes the AIDS virus receptor and is expressed in the immune system and the brain. Cell. 1986;47:333–348. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lannutti BJ, Drachman JG. Lyn tyrosine kinase regulates thrombopoietin-induced proliferation of hematopoietic cell lines and primary megakaryocytic progenitors. Blood. 2004 May 15;103(10):3736–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Cheng H, Hoxie JP, Parks WP. The conserved core of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef is essential for association with Lck and for enhanced viral replication in T-lymphocytes. Virology. 1999;264:5–15. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hanna Z, Weng X, Kay DG, Poudrier J, Lowell C, Jolicoeur P. The Pathogenicity of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Type 1 Nef in CD4C/HIV Transgenic Mice Is Abolished by Mutation of Its SH3-Binding Domain, and Disease Development Is Delayed in the Absence of Hck. J Virol. 2001;75(19):9378–9392. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.9378-9392.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Briggs SD, Lerner EC, Smithgall TE. Affinity of Src family kinase SH3 domains for HIV Nef in vitro does not predict kinase activation by Nef in vivo. Biochemistry. 2000;39(3):489–95. doi: 10.1021/bi992504j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Li Z, Nardi MA, Karpatkin S. Role of molecular mimicry to HIV-1 peptides in HIV-1-related immunologic thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2005;106(2):572–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Dexter TM, Allen TD, Lajtha LG. Conditions controlling the proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells in vitro. J. Cell Physiol. 1977;91:335–344. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040910303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Whitlock CA, Witte ON. Long-term culture of B lymphocytes and their precursors from murine bone marrow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79:3608–3612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.11.3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Torok-Storb B, Iwata M, Graf L, Gianotti J, Horton H, Byrne MC. Dissecting the marrow microenvironment. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1999;872:164–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Li L, Milner LA, Deng Y, et al. The human homolog of rat Jagged1 expressed by marrow stroma inhibits 32D cells through interaction with Notch1. Immunity. 1998;8:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Koka PS, Brooks DG, Razai A, Kitchen CM, Zack JA. HIV type 1 infection alters cytokine mRNA expression in thymus. AIDS research and Human Retroviruses. 2003;19(1):1–12. doi: 10.1089/08892220360473916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Van Overstraeten-Schlogel N, Beguin Y, Gothot A. Role of stromal-derived factor-1 in the hematopoietic-supporting activity of human mesenchymal stem cells. Eur. J. Haematol. 2006 Feb 23; doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2006.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Koka PS, Kitchen CMR, Reddy ST. targeting c-Mpl for revival of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-induced hematopoietic inhibition when CD34+progenitor cells are re-engrafted into a fresh stromal microenvironment in vivo. J. Virol. 2004;78(20):11385–11392. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11385-11392.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Zweegman S, Van Den Born J, Mus AM, Kessler FL, Janssen JJ, Netelenbos T, Huijgens PC, Drager AM. Bone marrow stromal proteoglycans regulate megakaryocytic differentiation of human progenitor cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2004 Oct 1;299(2):383–92. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zauli G, Re MC, Gugliotta L, Visani G, Vianelli N, Furlini G, La Placa M. Lack of compensatory megakaryopoiesis in HIV-1-seropositive thrombocytopenic individuals compared with immune thrombocytopenic purpura patients. AIDS. 1991;5(11):1345–50. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Miguez MJ, Rodriguez A, Hadrigan S, Asthana D, Burbano X, Fletcher MA. Interleukin-6 and platelet protagonists in T lymphocyte and virological response. Platelets. 2005;16(5):281–6. doi: 10.1080/09537100400028727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Van Wyk V, Kotze HF, Heyns AP. Kinetics of indium-111-labelled platelets in HIV-infected patients with and without associated thrombocytopaenia. Eur. J. Haematol. 1999 May;62(5):332–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1999.tb01911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ballem PJ, Belzberg A, Devine DV, Lyster D, Spruston B, Chambers H, Doubroff P, Mikulash K. Kinetic studies of the mechanism of thrombocytopenia in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992 Dec 17;327(25):1779–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212173272503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Dominguez A, Gamallo G, Garcia R, Lopez-Pastor A, Pena JM, Vazquez JJ. Pathophysiology of HIV related thrombocytopenia: an analysis of 41 patients. J. Clin. Pathol. 1994;47(11):999–1003. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.11.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Aboulafia DM, Bundow D, Waide S, Bennet C, Kerr D. Initial observations on the efficacy of highly active antiretroviral therapy in the treatment of HIV-associated autoimmune thrombocytopenia. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2000;320(2):117–23. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200008000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Grelli S, d’Ettorre G, Lauria F, Montella F, Di Traglia L, Lichtner M, Vullo V, Favalli C, Vella S, Mastino A. Inverse correlation between CD8+ lymphocyte apoptosis and CD4+ cell counts during potent antiretroviral therapy in HIV patients. J. Antimicrob Chemother. 2004 Mar;53(3):494–500. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Weinberg K, Annett G, Kashyap A, Lenarsky C, Forman SJ, Parkman R. The effect of thymic function on immunocompetence following bone marrow transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 1995;1:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Bolotin E, Smogorzewska M, Smith S, Widmer M, Weinberg K. Enhancement of thymopoiesis after bone marrow transplant by in vivo interleukin-7. Blood. 1996;88:1887–1894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Bolotin E, Annett G, Parkman R, Weinberg K. Serum levels of IL-7 in bone marrow transplant recipients: relationship to clinical characteristics and lymphocyte count. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:783–788. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Napolitano LA, Grant RM, Deeks SG, et al. Increassed production of IL-7 accompanies HIV-1-mediated T-cell depletion: implications for T-cell homeostasis. Nat. Med. 2001;7:73–79. doi: 10.1038/83381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Korin YD, Zack JA. Progression to the G1b phase of the cell cycle is required for completion of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcription in T cells. J. Virol. 1998;72:3161–3168. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3161-3168.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Uittenbogaart CH, Anisman DJ, Zack JA, Economides A, Schmid I, Hays EF. Effects of cytokines on HIV-1 production by thymocytes. Thymus. 1995;23:155–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Uittenbogaart CH, Boscardin WJ, Anisman-Posner DJ, Koka PS, Bristol G, Zack JA. Effect of cytokines on HIV-induced depletion of thymocytes in vivo. AIDS. 2000 Jul 7;14(10):1317–25. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200007070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Chun TW, Engel D, Mizell SB, Hallahan CW, Fischette M, Park S, Davey RT, Jr, Dybul M, Kovacs JA, Metcalf JA, Mican JM, Berrey MM, Corey L, Lane HC, Fauci AS. Effect of interleukin-2 on the pool of latently infected, resting CD4+ T cells in HIV-1-infected patients receiving highly active anti-retroviral therapy. Nat. Med. 1999;5:651–655. doi: 10.1038/9498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Stellbrink HJ, van Lunzen J, Westby M, O’Sullivan E, Schneider C, Adam A, Weitner L, Kuhlmann B, Hoffmann C, Fenske S, Aries PS, Degen O, Eggers C, Petersen H, Haag F, Horst HA, Dalhoff K, Mocklinghoff C, Cammack N, Tenner-Racz K, Racz P. Effects of interleukin-2 plus highly active antiretroviral therapy on HIV-1 replication and proviral DNA (COSMIC trial) AIDS. 2002;26:1479–1487. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207260-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Kulkosky J, Nunnari G, Otero M, Calarota S, Dornadula G, Zhang H, Malin A, Sullivan J, Xu Y, DeSimone J, Babinchak T, Stern J, Cavert W, Haase A, Pomerantz RJ. Intensification and stimulation therapy for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reservoirs in infected persons receiving virally suppressive highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;186:1403–1411. doi: 10.1086/344357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Emery S, et al. Pooled analysis of 3 randomized, controlled trials of interleukin-2 therapy inadult human immunodeficiency virus type 1 disease. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;182:428–434. doi: 10.1086/315736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Pandolfi F, Pierdominici M, Marziali M, Livia Bernardi M, Antonelli G, Galati V, D’Offizi G, Aiuti F. Low-dose IL-2 reduces lymphocyte apoptosis and increases naive CD4 cells in HIV-1 patients treated with HAART. Clin. Immunol. 2000;94:153–159. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Pett SL, Emery S. Immunomodulators as adjunctive therapy for HIV-1 infection. J. Clin. Virol. 2001;22:289–295. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(01)00201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Tambussi G, Ghezzi S, Nozza S, Vallanti G, Magenta L, Guffanti M, Brambilla A, Vicenzi E, Carrera P, Racca S, Soldini L, Gianotti N, Murone M, Veglia F, Poli G, Lazzarin A. Efficacy of low-dose intermittent subcutaneous interleukin (IL)-2 in antiviral drug-experienced human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons with detectable virus load: a controlled study of 3 IL-2 regimens with antiviral drug therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2001;183:1476–1484. doi: 10.1086/320188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Llano A, Barretina J, Gutierrez A, Blanco J, Cabrera C, Clotet B, Este JA. Interleukin-7 in plasma correlates with CD4 T-cell depletion and may be associated with emergence of syncytium-inducing variants in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-positive individuals. J. Virol. 2001;21:10319–10325. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10319-10325.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Resino S, Galan I, Correa R, Pajuelo L, Bellon JM, Munoz-Fernandez MA. Homeostatic role of IL-7 in HIV-1 infected children on HAART: association with immunological and virological parameters. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94(2):170–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Swiss Group for the Clinical Studies on AIDS Zidovudine for the treatment of thrombocytopenia associated with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Annals of Internal Medicine. 1988;109:718–721. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-9-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Jackson GG, Paul DA, Falk LA, Rubenis M, Despotes JC, Mack D, Knigge M, Emeson EE. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antigenemia (p24) in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and the effect of treatment with zidovudine (AZT) Ann. Intern. Med. 1988 Feb;108(2):175–80. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-2-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Servais J, Lambert C, Fontaine E, Plesseria JM, Robert I, Arendt V, Staub T, Schneider F, Hemmer R, Burtonboy G, Schmit JC. HIV-associated hematologic disorders are correlated with plasma viral load and improve under highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 2001 Nov 1;28(3):221–5. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200111010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Burbano X, Miguez MJ, Lecusay R, Rodriguez A, Ruiz P, Morales G, Castillo G, Baum M, Shor-Posner G. Thrombocytopenia in HIV-infected drug users in the HAART era. Platelets. 2001 Dec;12(8):456–61. doi: 10.1080/09537100120093956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Carbonara S, Fiorentino G, Serio G, Maggi P, Ingravallo G, Monno L, Bruno F, Coppola S, Pastore G, Angarano G. Response of severe HIV-associated thrombocytopenia to highly active antiretroviral therapy including protease inhibitors. J. Infect. 2001 May;42(4):251–6. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2001.0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Rarick MU, Burian P, de Guzman N, Espina B, Montgomery T, Jamin D, Levine AM. Intravenous immune globulin use in patients with human immunodeficiency virus-related thrombocytopenia who require dental extraction. West J. Med. 1991 Dec;155(6):610–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Stellini R, et al. Interferon therapy in intravenous drug users with HIV-associated idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Haematologica. 1992;77:418–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Vianelli N, et al. Recombinant alpha-interferon 2b in the treatment of HIV-related thrombocytopenia. AIDS. 1993;7:823–827. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199306000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Bain BJ. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of anemia in HIV infection. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 1999 Mar;6(2):89–93. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Sipsas NV, Kokori SI, Ioannidis JP, Kyriaki D, Tzioufas AG, Kordossis T. Circulating autoantibodies to erythropoietin are associated with human immunodeficiency virus type 1-related anemia. J. Infect. Dis. 1999;180(6):2044–7. doi: 10.1086/315156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Fangman JJ, Scadden DT. Anemia in HIV-infected adults: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical management. Curr. Hematol. Rep. 2005 Mar;4(2):95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Levy JA. HIV-1 hitching a ride on erythrocytes. Lancet. 2002;359:2212–2213. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Hess C, Klimkait T, Schlapbach L, Del Zenero V, Sadallah S, Horakova E, Balestra G, Werder V, Schaefer C, Battegay M, et al. Association of a pool of HIV-1 with erythrocytes in vivo: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002;359:2230. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Cameron PU, Freudenthal PS, Barker JM, Gezelter S, Inaba K, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells exposed to human immunodeficiency virus type-1 transmit a vigorous cytopathic infection to CD4+ T cells. Science. 1992;257:383–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1352913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Pohlmann S, Leslie GJ, Edwards TG, et al. DC-SIGN interactions with human immunodeficiency virus; virus binding and transfer are dissociable functions. J. Virol. 2001;75:10523–26. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10523-10526.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Jakubik JJ, Saifuddin M, Takefman DM, Spear GT. Immune complexes containing human immunodeficiency type 1 primary isolates bind to lymphoid tissue B lymphocytes and are infectious for T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 2000;74:552–55. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.552-555.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Olinger GG, Saifuddin M, Spear GT. CD-4 negative cells bind human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and efficiently transfer virus to T cells. J. Virol. 2000;74:8550–57. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8550-8557.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Moir S, Malaspina A, Li Y, et al. B cells of HIV-1-infected patients bind virions through CD21-complement interactions and transmit infectious virus to activated T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:637–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Hess C, Klimkait T, Schlapbach L, Del Zenero V, Sadallah S, Horakova E, Balestra G, Werder V, Schaefer C, Battegay M, Schifferli JA. Association of a pool of HIV-1 with erythrocytes in vivo: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002 Jun 29;359(9325):2230–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Horakova E, Gasser O, Sadallah S, Inal JM, Bourgeois G, Ziekau I, Klimkait T, Schifferli JA. Complement mediates the binding of HIV to erythrocytes. J. Immunol. 2004 Sep 15;173(6):4236–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Sullivan PS, Hanson DL, Chu SY, Jones JL, Ward JW. Epidemiology of anemia in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected persons: results from the multistate adult and adolescent spectrum of HIV disease surveillance project. Blood. 1998;91(1):301–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Mauss S, Steinmetz HT, Willers R, Manegold C, Kochanek M, Haussinger D, Jablonowski H. Induction of Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor by Acute Febrile Infection but Not by Neutropenia in HIV-Seropositive Individuals. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 1997 April 15;14(5):430–434. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199704150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Moore DA, Sullivan A, Hilstead P, Gazzard BG. A retrospective study of neutropenia in HIV disease. Int. J. STD. AIDS. 2000;11(1):8–14. doi: 10.1258/0956462001914832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Meynard JL, Guiguet M, Arsac S, Frottier J, Meyohas MC. Frequency and risk factors of infectious complications in neutropenic patients infected with HIV. AIDS. 1997 Jul;11(8):995–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Costantini A, Giuliodoro S, Mancini S, Butini L, Regnery CM, Silvestri G, Greco F, Leoni P, Montroni M. Impaired in-vitro growth of megakaryocytic colonies derived from CD34 cells of HIV-1-infected patients with active viral replication. AIDS. 2006 Aug 22;20(13):1713–20. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000242817.88086.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Kline MW, Blanchard S, Fletcher CV, Shenep JL, McKinney RE, Jr, Brundage RC, Culnane M, Van Dyke RB, Dankner WM, Kovacs A, McDowell JA, Hetherington S, AIDS Clinical Trials Group 330 Team A phase I study of abacavir (1592U89) alone and in combination with other antiretroviral agents in infants and children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatrics. 1999 Apr;103(4):e47. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.4.e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Grella M, Ofosu JR, Klein BL. Prolonged oral acyclovir administration associated with neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1998 Jul;16(4):396–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(98)90138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Joly V, Geoffray C, Reynes J, Goujard C, Mechali D, Maslo C, Raffi F, Yeni P. Amphotericin B in a lipid emulsion for the treatment of cryptococcal meningitis in AIDS patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1996 Jul;38(1):117–26. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Safrin S, Finkelstein DM, Feinberg J, Frame P, Simpson G, Wu A, Cheung T, Soeiro R, Hojczyk P, Black JR, ACTG 108 Study Group Comparison of three regimens for treatment of mild to moderate Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with AIDS. A double-blind, randomized, trial of oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, dapsone-trimethoprim, and clindamycin-primaquine. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996 May 1;124(9):792–802. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-9-199605010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Freund YR, Dousman L, Riccio ES, Sato B, MacGregor JT, Mohagheghpour N. Immunohematotoxicity studies with combinations of dapsone and zidovudine. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2001 Nov;1(12):2131–41. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Valganciclovir: new preparation. CMV retinitis: a simpler, oral treatment. Prescrire Int. 2003 Aug;12(66):133–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Sattler FR, Allegra CJ, Verdegem TD, Akil B, Tuazon CU, Hughlett C, Ogata-Arakaki D, Feinberg J, Shelhamer J, Lane HC, et al. Trimetrexate-leucovorin dosage evaluation study for treatment of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 1990 Jan;161(1):91–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Martinez E, Collazos J, Mayo J. Hypersensitivity reactions to rifampin. Pathogenetic mechanisms, clinical manifestations, management strategies, and review of the anaphylactic-like reactions. Medicine (Baltimore) 1999 Nov;78(6):361–9. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199911000-00001. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Nicolau DP, Ross JW, Quintiliani R, Nightingale CH. Pharmacoeconomics of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in HIV-infected and HIV-noninfected patients. Pharmacoeconomics. 1996 Jul;10(1):72–8. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199610010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Gordin FM, Simon GL, Wofsy CB, Mills J. Adverse reactions to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann. Intern. Med. 1984 Apr;100(4):495–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-4-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]