Abstract

Dopamine (DA) reuptake terminates dopaminergic neurotransmission and is mediated by DA transporters (DATs). Acute protein kinase C (PKC) activation accelerates DAT internalization rates, thereby reducing DAT surface expression. Basal DAT endocytosis and PKC-stimulated DAT functional downregulation rely on residues within the 587–596 region, although whether PKC-induced DAT downregulation reflects transporter endocytosis mechanisms linked to those controlling basal endocytosis rates is unknown. Here, we define residues governing basal and PKC-stimulated DAT endocytosis. Alanine substituting DAT residues 587–590 1) abolished PKC stimulation of DAT endocytosis, and 2) markedly accelerated basal DAT internalization, comparable to that of wildtype DAT during PKC activation. Accelerated basal DAT internalization relied specifically on residues 588–590, which are highly conserved among SLC6 neurotransmitter transporters. Our results support a model whereby residues within the 587–590 stretch may serve as a locus for a PKC–sensitive braking mechanism that tempers basal DAT internalization rates.

INTRODUCTION

DA is a major central nervous system neurotransmitter that is required for appropriate motor function (Brooks, 2001) and rewarding behaviors (Wise, 1996; Nestler, 2005; Hyman et al., 2006). DA signaling is implicated in schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and treatments targeting these disorders modulate dopaminergic neurotransmission (De Oliveira and Juruena, 2006; Runyon and Carroll, 2006; Carlsson et al., 2007). Extracellular DA levels are regulated by the plasma membrane DAT, which removes DA from the synaptic cleft thereby temporally and spatially constraining DA availability. Disrupting DAT function either by genetic or pharmacological means has significant physiological consequences. DAT (−/−) and knockdown mice exhibit sustained extracellular DA levels following evoked release (Giros et al., 1996; Zhuang et al., 2001), and have significantly reduced DA tissue levels (Jones et al., 1998), consistent with DAT’s role in neurotransmission and in maintaining normal dopaminergic tone. Addictive psychostimulants such as cocaine and amphetamines competitively inhibit DAT (Amara and Sonders, 1998; Rothman and Baumann, 2003), leading to elevated extraneuronal DA levels and enhanced synaptic responses. Moreover, a recent knock-in mouse study using a cocaine-insensitive DAT mutant demonstrated a critical role for DAT in establishing conditioned place preference to cocaine (Chen et al., 2006).

DAT is a member of high affinity sodium- (Na+) and chloride (Cl−)-dependent SLC6 transporter gene family, which also includes transporters for neurotransmitters serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine (NE), γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) and glycine (Chen et al., 2004; Gether et al., 2006). All members of the family share a similar predicted topology of twelve transmembrane domains, cytoplasmic amino- and carboxy- terminals, a large second extracellular loop with multiple N-linked glycosylation sites, and cytoplasmic phosphorylation sites. Recent crystallographic studies focusing on LeuTAa, a bacterial SLC6 transporter homolog, support the predicted DAT topology and reveal a dimeric transporter assembly (Yamashita et al., 2005), consistent with FRET and co-immunoprecipitation studies that suggest SLC6 transporter homooligomerization (Schmid et al., 2001; Scholze et al., 2002; Sorkina et al., 2003; Torres et al., 2003b).

Recent reports indicate that DAT is not static at the cell surface; rather DAT dynamically cycles to and from the plasma membrane under basal conditions as observed in PC12 (Loder and Melikian, 2003; Holton et al., 2005; Boudanova, 2008), PAE (Sorkina et al., 2005), and HEK (Li et al., 2004) cell lines. In PC12 and HEK cell lines, DAT basally internalizes at rates of 2–3% per minute, which corresponding to a surface t1/2 ~13 minutes (Loder and Melikian, 2003; Li et al., 2004; Boudanova, 2008). Acute PKC activation decreases DAT surface levels by increasing DAT endocytic rates (Loder and Melikian, 2003; Sorkina et al., 2005) and, in parallel, decreasing DAT recycling rates (Loder and Melikian, 2003). Recent siRNA studies suggest that both constitutive and PKC-stimulated DAT endocytosis are clathrin-mediated (Sorkina et al., 2005), and that Nedd 4-2-dependent DAT ubiquitination on amino terminal residues is also required for PKC-stimulated DAT internalization (Sorkina et al., 2006; Miranda et al., 2007). In a previous report from our laboratory, we demonstrated that constitutive DAT endocytosis and PKC-mediated DAT downregulation rely on overlapping, but distinct, endocytic signals encoded by DAT carboxy terminal amino acids 587–596 (Holton et al., 2005). The DAT endocytic signal does not conform to classic dileucine- and/or tyrosine-based endocytic motifs, and is conserved among mammalian SLC6 neurotransmitter transporters, suggesting that specialized endocytic mechanisms may facilitate DAT internalization. Although the previous study identified DAT residues required for PKC-induced DAT downregulation, it did not specify endocytosis as the mechanism for downregulation nor how these relate to basal endocytosis determinants. Here we used site-directed mutagenesis to define the determinants of basal and PKC-stimulated DAT endocytosis Our results suggest that basal and PKC-stimulated DAT internalization may not occur by separate cellular mechanisms. Rather, a molecular brake is likely to temper basal DAT endocytic rates and PKC activation accelerates DAT endocytosis by relieving this braking mechanism.

RESULTS

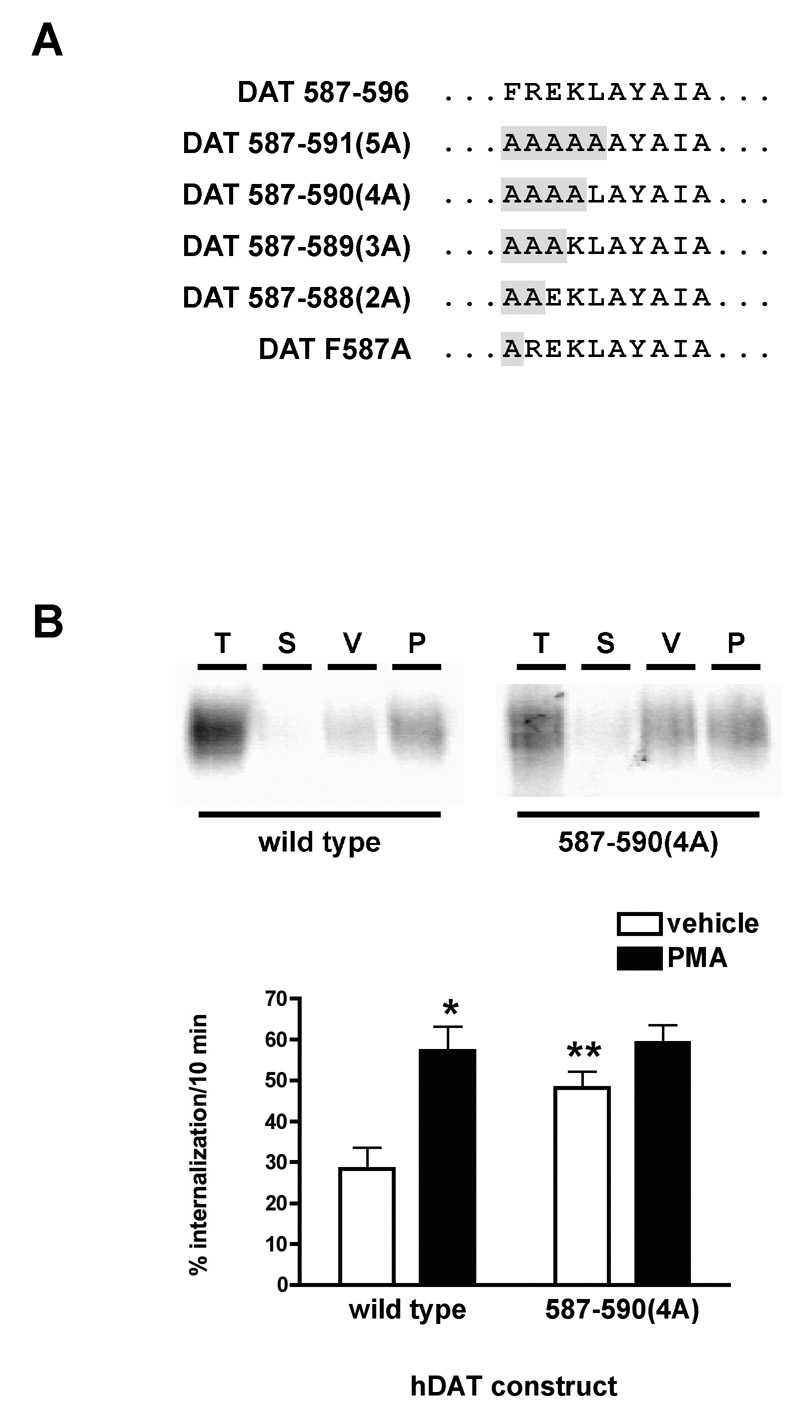

We previously reported that DAT carboxy terminal residues 587–596 were sufficient to drive endocytosis of the reporter molecule, Tac, and that residues L591, Y593 and I595 within the 587–596 span were required for basal DAT endocytosis, but not PKC-mediated DAT functional downregulation and intracellular sequestration (Holton et al., 2005). Moreover, alanine substitution of either residues 587–596 (FREKLAYAIA) or 587–591 (FREKL) completely abolished PKC-mediated DAT functional downregulation as assessed by [3H]DA uptake assay. Although PKC-modulated DAT endocytosis was not assessed in our prior study, it seemed possible that distinct but overlapping endocytic signals could be contained within FREKLAYAIA, such that separate endocytic mechanisms could facilitate basal and PKC-stimulated DAT internalization. We sought to determine whether the basal and PKC-sensitive DAT endocytic signals were entirely independent or, alternatively, were synergistic. Since the 587–591 alanine substitution included L591, a residue also required for basal DAT internalization, we first generated a DAT mutant in which only residues 587–590 were alanine substituted (DAT 587–590(4A), see Fig. 1A), and tested whether PKC activation accelerated the endocytic rate of this mutant comparable to wildtype DAT. Using a reversible biotinylation approach, we measured wildtype and 587–590(4A) internalization over a 10 minute time period ±1µM PMA in pooled, stably transfected PC12 cell lines. Consistent with previous reports (Loder and Melikian, 2003; Holton et al., 2005), wildtype DAT constitutively internalized at 28.3 ±5.3%/10 min (Fig. 1B). PKC activation significantly increased DAT internalization rates to 57.2 ±6.0%/10 min, which translates into a 124.4 ±33.3% increase in the DAT endocytic rate (Fig. 1B). Surprisingly, alanine substitution of DAT residues 587–590 significantly increased basal DAT endocytic rates as compared to wildtype DAT, to 48.1 ±4.1%/10 min (Fig. 1B). The increased 587–590(4A) basal internalization rate was not significantly different to that observed for wildtype DAT following PKC activation (p>0.05, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison test, n=6–7), and PKC activation did not further increase 587–590(4A) endocytic rates over its basal rate (p>0.05, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison test, n=7).

Figure 1. Alanine substitution of DAT residues 587–590 (FREK) increases basal, and abolishes PKC-accelerated, DAT endocytosis.

A) Model illustrating the DAT endocytic signal spanning carboxy terminal residues 587–596 (FREKLAYAIA), and the alanine substitution mutants generated. B) Internalization assay. Stably transfected PC12 cells were biotinylated at 4°C and internalization was monitored for 10 min, 37°C, ±1 µM PMA, as described in Experimental Methods. Top: Representative immunoblots displaying total surface DAT at time zero (T), Strip controls (S), and amount of DAT internalized (10 min, 37°C) in the presence of either vehicle (V) or 1µM PMA (P). Bottom: Averaged data. Values indicate the %surface DAT internalized over 10 min ±S.E.M. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from wildtype internalization in the presence of vehicle. *p<0.01, **p<0.05, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Test, n=6–7.

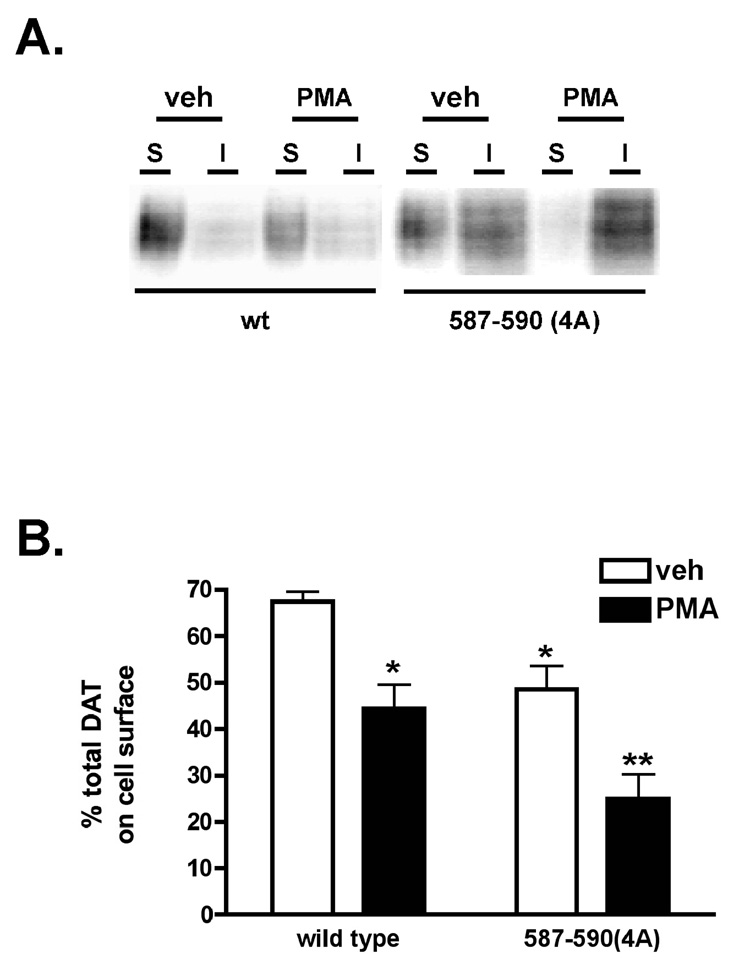

Given that 587–590(4A) endocytic rates do not appreciably increase in response to PKC activation, we used cell surface biotinylation to ask whether PKC activation induced losses in 587–590(4A) surface expression. PKC activation significantly reduced wildtype DAT surface levels from 67.4±2.2% to 44.4±5.2% total DAT, with translates into a 37.2±6.7% loss of surface protein (Fig. 2). Under basal conditions, significantly less 587–590(4A) was expressed on the cell surface as compared to wildtype DAT (67.4± 2.2% total wildtype vs. 48.5±5.1% total 587–590(4A), p<.05, Student’s t test, n=4), and PKC activation significantly decreased 587–590(4A) surface levels to 25±5.4% of total DAT, which translates into a 48.7±7.9% loss of surface DAT (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. DAT residues 587–590 (FREK) are not required for PKC-mediated DAT sequestration and PKC-induced functional downregulation.

Cell surface biotinylation. PC12 cells stably transfected with the indicated cDNAs were treated ±1µM PMA, 30 min, 37°C followed by cell surface biotinylation as described in Experimental Methods. Top: Representative immunoblots displaying surface (S) and intracellular (I) DAT fractions following treatment with either vehicle (veh) or PMA. Bottom: Averaged data. Bars represent %total DAT on cell surface ± S.E.M. *Significantly different from vehicle-treated wildtype DAT, **Significantly different from vehicle-treated DAT 587–590(4A) (p<0.05, One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison test, n=4–9).

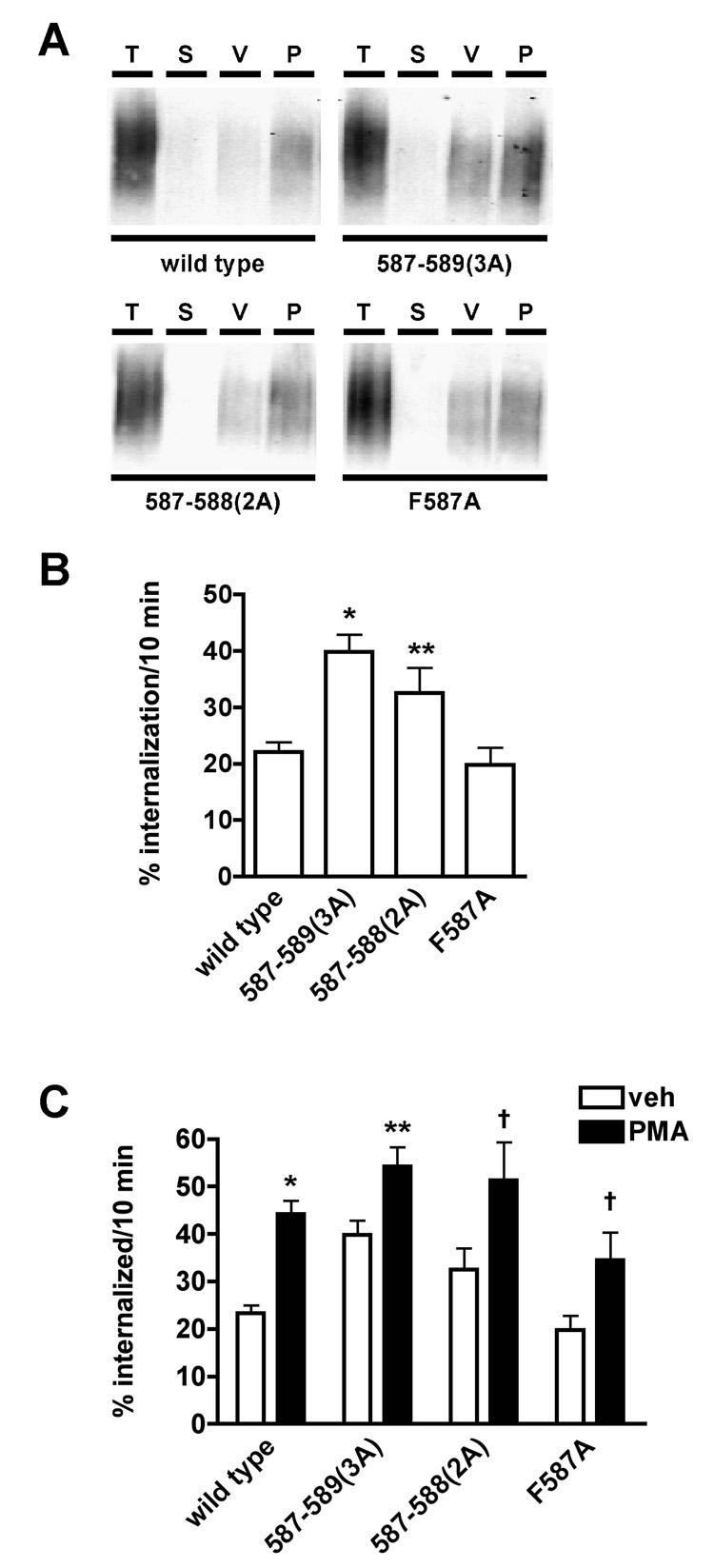

Given that the FREK residues are highly conserved in the SLC6 transporter gene family, we next used mutagenesis to test which residues within the 587–590 stretch were specific determinants of 1) the DAT basal endocytic rate and 2) PKC-accelerated DAT endocytosis. We serially restored one amino acid at a time to the 587–590(4A) mutant (see schematic, Fig. 1A), and measured the resulting mutant DAT internalization rates, under both basal and PKC-activated conditions in transiently transfected PC12 cells. Addition of K590 and E589 was not sufficient to restore DAT basal endocytic rates back to wildtype levels, as both the DAT 587–589(3A) and 587–588(2A) mutants exhibited significantly higher basal endocytic rates than wildtype DAT (Fig. 3A, 3B), and which were not significantly different from those of wildtype DAT during PKC activation (Fig. 3C, p<.05, One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison test, n=11–28). Further addition of R588 (F587A) yielded a mutant DAT with basal endocytic rates that were comparable to wildtype levels (p>0.05, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, n=11–25), and that were significantly lower than both 587–588(2A) and 587–589(3A) (Fig. 3B).We next tested whether residues within the 587–589 stretch were required for PKC stimulated endocytic rates. Addition of K590 was sufficient to restore DAT PKC sensitivity, as the DAT 587–589(3A), 587–588(2A) and F587A mutants all exhibited significant PKC-enhanced endocytosis (Fig. 3C). Moreover, there was no significant difference in the magnitude of the PKC effect on any of the mutants, as compared to wildtype (p>.05, One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, n=9–22). Identical results were obtained for basal and PKC-stimulated endocytosis of wildtype, 587–589(3A) and F587A DAT in stably transfected cells lines (DAT 587–588(2A) not assessed in stable cell lines). Taken together with our 587–590(4A) internalization results, these data reveal an overlapping, but distinct dependence on structural aspects in the 587–590 region in mediating basal versus PKC-accelerated DAT endocytosis.

Figure 3. Amino acids with the DAT 587–589 region influence constitutive and PKC-stimulated DAT endocytosis.

Internalization assays. PC12 cells transfected with the indicated DAT constructs were biotinylated at 4°C and internalization was monitored for 10 min, 37°C ±1µMPMA as described in Experimental Methods. A) Representative immunoblots displaying total surface DAT at time zero (T), strip controls (S), and amount of DAT internalized (10 min, 37°C) in the presence of either vehicle (V) or 1µM PMA (P) for wildtype and the indicated DAT mutants. B) Basal internalization rates. Averaged data are shown and values indicate the endocytic rate a% surface internalized over 10 min ±S.E.M. in the presence of vehicle. *Significantly different from wildtype and F587A, p<.001; **Significantly different from wildtype and F587A, p<.05; One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Test, n=11–25. C) The effect of PKC stimulation on DAT endocytic rates. Averaged data are shown and values indicate the % internalized from the surface over 10 min ±S.E.M following treatment with either vehicle (veh, open bars) or PMA (PMA, filled bars). Symbols indicate significantly different from vehicle-treated control: *p<.0001, **p<.01, =p<.05, Student’s t test, n=9–22.

To assure that the trafficking differences observed were not due to altered surface expression, we also measured DAT kinetic values for F587A, 587–589(3A) and 587–590(4A) DAT mutants as compared to wildtype DAT in stably transfected cells lines. These results are presented in Table I. The 587–590(4A) mutation significantly decreased DAT Vmax values, as compared to wildtype, whereas neither the F87A nor 587–589(3A) mutations significantly affected DAT Vmax values, although there was a trend for a decreased 587–589(3A) Vmax value. Km values for all the mutants were not significantly different from wildtype (p>.05, One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison test, n=4–11). Similar results were obtained in transiently transfected cells (not shown).

Table I.

Kinetics analysis of DAT mutants expressed in PC12 cells

| DAT construct | Vmax (pmole/min/mg) | Km (µM) | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| wild type | 14.3 ± 2.36 | 1.35 ± 0.08 | 11 |

| F587A | 21.2 ± 3.89 | 1.41 ± 0.20 | 5 |

| 587–589(3A) | 6.4 ± 0.84 | 1.08 ± 0.13 | 5 |

| 587–590(4A) | 2.3 ± 1.12* | 1.66 ± 0.55 | 4 |

Significantly different from wild type, p<.05, One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison test

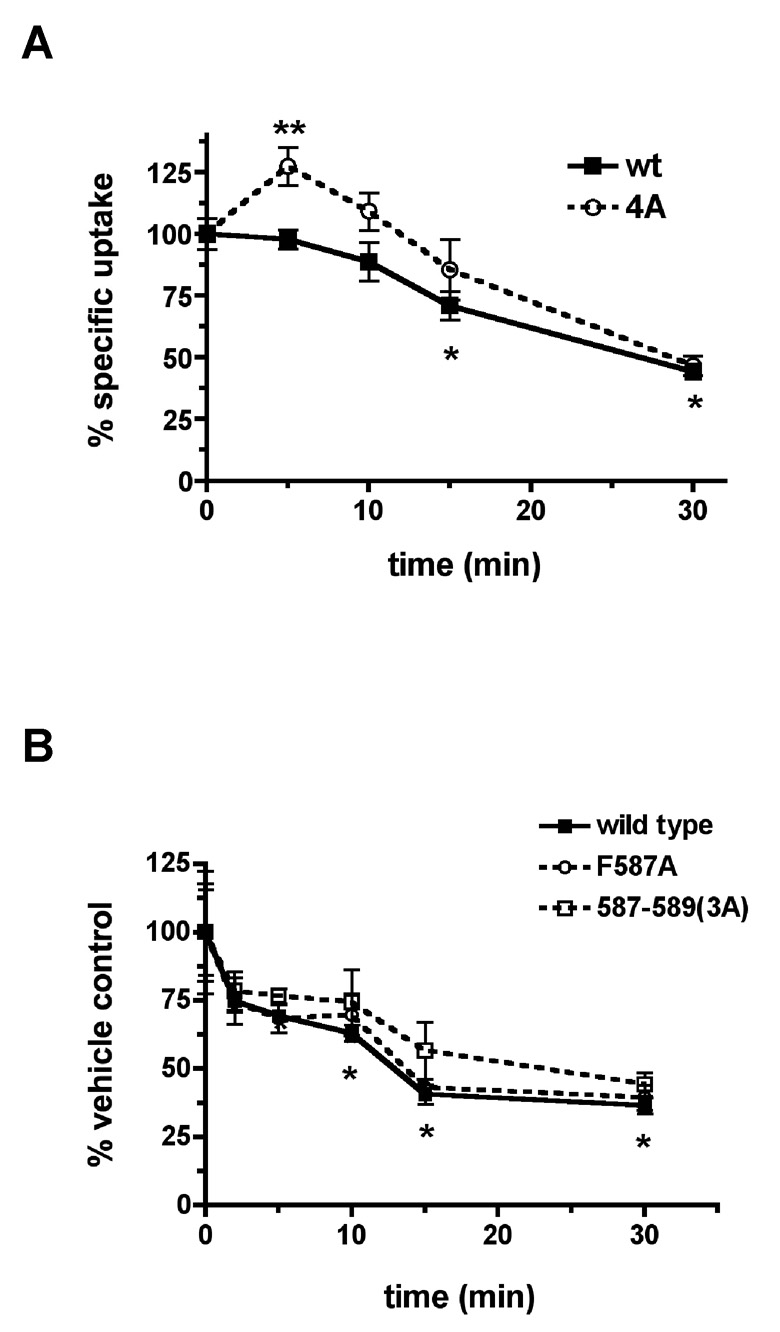

We next asked whether the loss of PKC-enhanced endocytosis was sufficient to abolish PKC-mediated DAT downregulation measured by [3H]DA uptake timecourses. We first assessed whether the 587–590 region was required for PKC-mediated downregulation by comparing wildtype vs. 587–590(4A) DAT. The results are shown in Figure 4A. Wildtype DAT significantly downregulated 15 minutes following PKC activation and achieved a 55.7% downregulation 30 minutes after PKC activation. The DAT 587–590(4A) mutant exhibited a significant increase in uptake (to 127.4% of baseline) as compared to wildtype 5 minutes after PKC activation, and then downregulated similarly to wildtype at the subsequent timepoints. Uptake assays comparing F587A and 587–589(3A) DAT mutants to wildtype revealed wildtype DAT was significantly downregulated 10 minutes following PKC activation, and achieved a 63.5% downregulation 30 minutes after PKC activation. Both F587A and 587–589(3A) DAT mutants downregulated similarly to wildtype at all timepoints measured (Fig. 4B). Thus, while residues within the 587–590 region play a role in maintaining the basal DAT endocytic rate, they are not required for PKC-mediated DAT downregulation.

Figure 4. DAT residues 587–590 are not required for PKC-mediated functional downregulation.

[3H]DA uptake assay. PC12 cells transfected with the indicated DAT constructs were treated with either vehicle or 1µM PMA for the indicated times and [3H]DA uptake was measured as described in Experimental Methods. Values are averaged data and indicate %specific DA uptake ±S.E.M. as compared to vehicle-treated controls for each construct. (A) Wild-type vs. DAT 587–590(4A). *Applies to the wildtype curve and indicates significantly less uptake than at t=0 (p<.01, One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison test, n=3). **Significantly different from wildtype, p<.03, Student’s t test, n=3. (B) Wild-type vs. DAT F587A, 587–589(3A). *Applies to the wildtype curve and indicates significantly less uptake than at t=0 (p<.05, One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison test, n=3).

DISCUSSION

Although it is well established that PKC activation acutely downregulates DAT (Zahniser and Doolen, 2001; Robinson, 2002; Torres et al., 2003a; Melikian, 2004), the specific mechanisms mediating PKC-induced losses in DAT function are not well defined. Numerous studies from both our laboratory (Melikian and Buckley, 1999; Loder and Melikian, 2003; Holton et al., 2005) and others (Zhu et al., 1997; Granas et al., 2003; Sorkina et al., 2005) have demonstrated a clear role for endocytic trafficking in maintaining basal DAT surface levels and mediating PKC-induced DAT downregulation. Previous results from our laboratory revealed that DAT carboxy terminal residues L591, Y593 and I595 are necessary for basal DAT endocytosis, whereas residues 587–591 (FREKL) are required for PKC-mediated DAT downregulation (Holton et al., 2005). These data raised the possibility that two independent mechanisms may govern constitutive and PKC-stimulated DAT internalization. However, while our previous study defined amino acids critical for PKC effects on DAT function, it did not directly examine which residues are integral to PKC-stimulated DAT endocytosis. In the current study, we used site-directed mutagenesis to specifically define the residues within FREKLAYAIA that play a role in PKC-stimulated DAT endocytosis and downregulation.

To our surprise, alanine substituting either 587–590 (FREK), 587–589 (FRE) or 587–588 (FR) significantly enhanced basal DAT internalization rates, to levels comparable to those of wildtype during PKC activation. These results suggest that DAT residues 587–590 (FREK) play a critical role in mediating DAT endocytic rates and may be integral to a negative regulatory, PKC-sensitive braking mechanism that tempers DAT endocytic rates under basal conditions, but is released upon PKC activation. Moreover, residues 587–590 were absolutely required for PKC acceleration of DAT endocytosis, while addition of K590 restored PKC sensitivity (Fig. 1B and Fig. 3C). While these results suggest that K590 is necessary for PKC-stimulated endocytosis, another possible interpretation of these results is that we have reached an “endocytic ceiling”, and cannot further increase DAT’s endocytic rate. However, we believe that this is not the case, as a recent report from our laboratory indicated that acute amphetamine exposure accelerates 587–590(4A) mutant endocytosis comparable to wildtype (Boudanova, 2008). It is also possible that differential expression levels of the mutant DATs may underlie their trafficking defects. To address this possibility, we compared Vmax values for wildtype, F587A, 587–589(3A) and 587–590(4A). Only the DAT 587–590(4A) mutant exhibited a significantly decreased Vmax value as compared to wildtype DAT (~6-fold lower). Given that both the 587–590(4A) and 587–589(3A) mutants exhibited enhanced basal endocytic rates, but that only 587–590(4A) surface expression differed from wildtype, it is not likely that DAT surface expression levels contribute to its endocytic rate. Previous work from our laboratory also supports this conclusion (Loder and Melikian, 2003). In our previous report, we compared basal DAT endocytic rates across clonal stably transfected PC12 cell lines and found no difference in DAT endocytic rates, despite a 50-fold difference in DAT expression levels.

Interestingly, the loss of PKC-stimulated endocytosis in the 587–590(4A) mutant did not abolish either PKC-induced functional downregulation or PKC-induced decreased DAT surface expression (Fig. 2). We previously reported that PKC activation both increases DAT endocytic rates, and decreases DAT recycling back to the plasma membrane (Loder and Melikian, 2003). Given that the DAT 587–590(4A) endocytic rate is comparable to that of wildtype during PKC activation, it is likely that its rapid basal endocytic rate of the 587–590(4A) mutant, coupled with PKC effects on recycling, are sufficient to retain the 587–590(4A) mutant intracellularly, thereby reducing surface levels and function. In support of this hypothesis, we measured 587–590(4A) recycling rates and found that they did not differ significantly from wildtype (results not shown). We also observed a significant increase in 587–590(4A) activity 5 minutes after phorbol ester application, but which did not persist throughout the timecourse (Fig. 4A). This may reflect PKC effects on DAT intrinsic activity, or differential effects on DAT internalization and recycling not detectable by our biochemically based assays. Future experiments will investigate this phenomenon in greater detail.

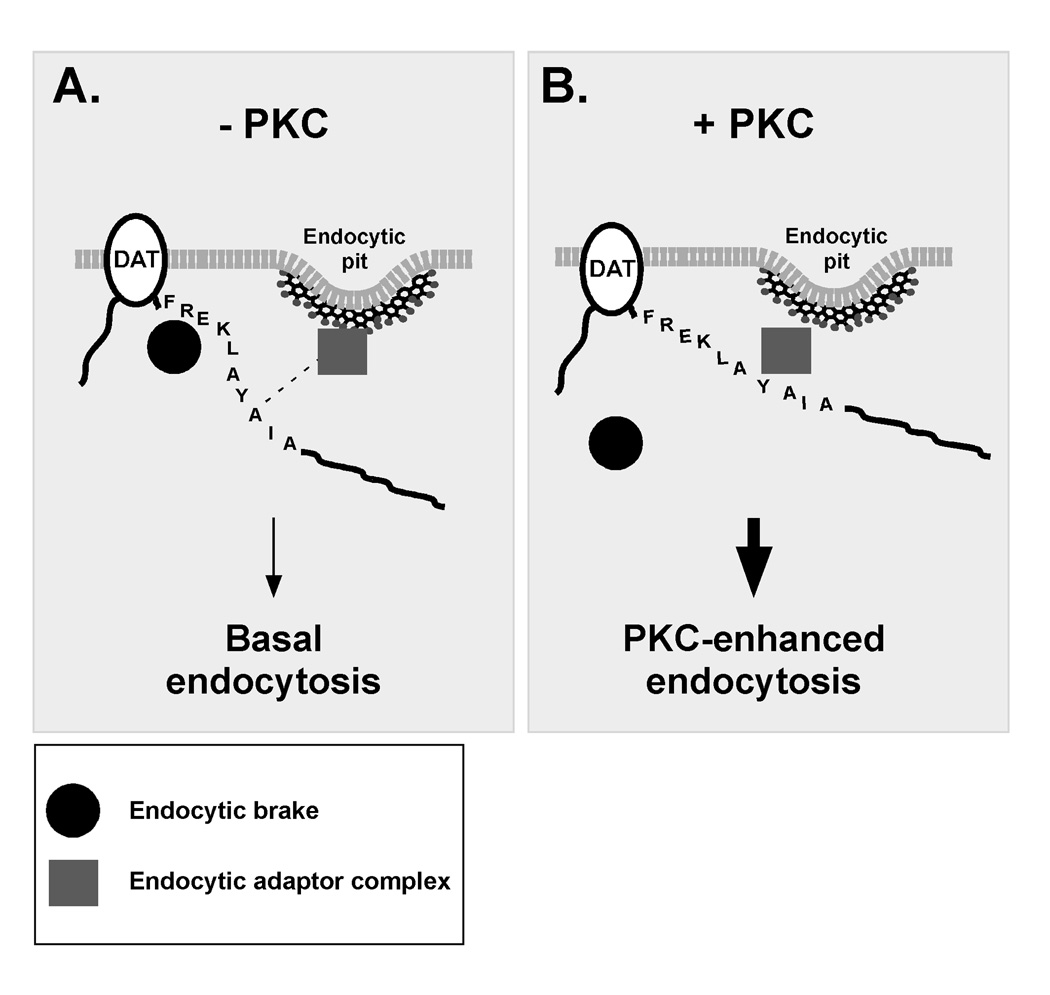

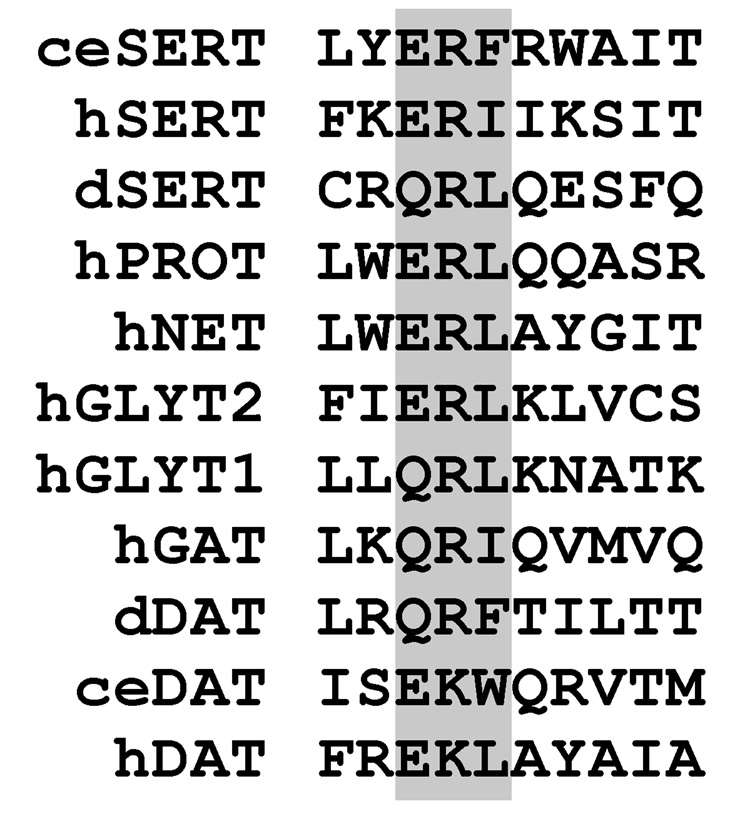

Based on our current and previous (Holton et al., 2005) findings, we propose that a synergistic braking mechanism is likely to modulate DAT endocytosis (see model, Fig. 5). In this model, an endocytic adaptor complex binds to or requires the DAT 591–596 region (LAYAIA), but a braking mechanism slows the rate of DAT internalization in a manner that requires DAT residues 587–590 (FREK). Mutating either L591, Y593 or I595 decreases the interaction with the endocytic machinery sufficiently to disrupt basal endocytosis. When PKC is activated, the braking mechanism dissociates, and DAT interactions with the endocytic machinery are strengthened, leading to enhanced endocytic rates. This strengthening is apparently capable of overcoming the influence of either L591, Y593 or I595 mutations, since these mutants still sequester in response to PKC activation (Holton et al., 2005). Given that residues 588–590 (REK) were required to temper basal DAT endocytic rates, it is likely that they play an important role in mediating endocytic braking. An alignment of SLC6 neuronal transporters reveals that all transporters within the gene family encode either a glutamate or glutamine at the position orthologous to DAT E589, while basic amino acids (arginine or lysine) are encoded across the gene family at the positions aligned to DAT K590 (Fig. 6). This conservation suggests that size, rather than charge, at position 589 is likely to be important for the brake’s actions, while charge is more likely to be a factor at position 590. We also note that a large, bulky hydrophobic residue at DAT residue L591, required for basal endocytosis (Holton et al., 2005), is conserved across the gene family. Additionally, although large bulky hydrophobic amino acids at DAT positions Y593 and I595 are conserved among GABA, DA, NE and 5-HT mammalian transporters, they are not conserved in glycine, proline and invertebrate carriers. This suggests that L591 may play a more critical role in basal endocytosis, or that other factors may contribute to regulating trafficking of other transporters in the gene family.

Figure 5. Model for a molecular brake that regulates DAT endocytic rates.

We predict that under basal conditions (A) DAT endocytic rates are tempered by a brake mechanism that binds to DAT residues 587–590 (FREK) and decreases the affinity between DAT residues 591–596 (LAYAIA) and an endocytic adaptor protein or protein complex. PKC stimulation (B) causes the brake to dissociate from DAT. With the brake dissociated, the affinity between LAYAIA and endocytic adaptor complex increases, significantly accelerating DAT internalization.

Figure 6. DAT residues within the 587–590 (FREK) region are highly conserved across the SLC6 transporter gene family.

Clustal alignment of hDAT587–596 region with neuronal SLC6 gene family members. ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; d, Drosophila melanogaster; h, human. The shaded box highlights residues orthologous to DAT 589–591. Note conservation of size for E589 (E or Q across the gene family) and charge for K590 (K or R across the gene family), as well as conservation of a large, bulky hydrophobic amino acid at position L591.

While the DAT carboxy terminus is clearly important for basal and PKC-induced DAT endocytosis, recent studies also point to a central role for the DAT amino terminus in these processes. PKC activation leads to increases in DAT ubiquitination (Miranda et al., 2005) that rely on the ubiquitin ligase Nedd 4-2 (Sorkina et al., 2006), and several ubiquitination sites in the DAT amino terminus appear to be required for PKC-induced DAT sequestration from the plasma membrane (Miranda et al., 2007). Currently it is not known whether the DAT amino and carboxy termini operate together or autonomously to facilitate constitutive and PKC-modulated DAT endocytosis.

We also observed a high proportion of immature, EndoH-sensitive DAT in cells expressing the 587–590(4A) mutant (data not shown). This is likely due to a slow ER exit for this mutant. Indeed, a role for K590 and L591 in sec24D binding and ER export has recently been reported for DAT, SERT and GAT (Farhan et al., 2007). It is interesting that the highly conserved K590 appears to play an important trafficking role, both at the level of ER exit and for regulated endocytosis. This may reflect biological redundancy, or may point to potential common mechanisms in recruiting coat proteins for membrane invagination and/or fission.

What cellular factors target the FREK region? The DAT carboxy terminus is a locus for a number of binding proteins that play a role in membrane targeting and regulation. However, DAT-interacting proteins identified thus far do not bind at or near the FREK stretch. PICK1 is known to bind to the distal region of the carboxy terminus (Torres et al., 2001; Bjerggaard et al., 2004), although its role in DAT trafficking is not well defined. Hic-5 binds to the DAT carboxy terminus in the 571–580 region, closely upstream of the FREKLAYAIA domain (Carneiro et al., 2002), and a recent study revealed a likely role for Hic-5 in PKC-mediated SERT downregulation (Carneiro and Blakely, 2006). A recent study also elegantly demonstrated PKC-modulated binding of CamKII to the DAT carboxy terminus that is necessary for amphetamine-induced DA efflux via DAT (Fog et al., 2006). However, CamKII binding was mapped to the distal region of the DAT carboxy terminus, and thus does not likely target the FREK region. Although the currently known DAT interactors are not likely candidates involved in governing DAT endocytic rates, future studies aimed at identifying FREKLAYAIA interacting proteins should reveal critical factors involved in this process.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Materials

Monoclonal rat anti-DAT antibodies were from Chemicon (Temecula, CA) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). [3H]DA (dihydroxyphenylethylamine 3,4-[ring-2,5,6,-3H] was from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA) and sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin was from Pierce (Rockford, IL). All other chemicals and reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and were of the highest grade possible.

cDNA constructs

hDAT cDNA were cloned into pcDNA 3.1(+) as previously described (Holton et al., 2005). Mutagenesis was performed with the Quikchange site-directed mutagenesis system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). All mutants were subcloned back into the parental hDAT plasmid at the ClaI/XbaI site. Sequences were verified by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Nucleic Acid Facility.

Cell culture, transfection, and stable cell lines

PC12 cells were maintained as previously described (Loder and Melikian, 2003) and were transiently transfected by electroporation. 1.1 × 107 cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 0.75 ml electroporation buffer (137 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM KCl, 0.7 mM Na2HPO4, 6.0 mM glucose, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.05) and were mixed with 18.2µg of the indicated plasmids. Cells were electroporated at 300mV, 500µF, with an exponential decay protocol, using a GenePulser Xcell unit (Biorad, Hercules, CA) with a CE module and 4.0 mm cuvettes. Following 30 min recovery in PC12 media containing 3 mM EGTA, cells were plated onto poly-D-lysine coated plates. All transfected cells were assayed 48–72 hrs post-transfection. For pooled stable PC12 cell lines, cells were transfected as indicated, above, and stable transformants were selected in the presence of 0.5 mg/ml geneticin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Pooled cell lines were maintained under selective pressure with 0.2 mg/ml geneticin.

[3H]DA uptake assay

Cells were washed in Krebs-Ringers-HEPES (KRH) buffer (120 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) and incubated for 30 min, 37 °C in KRH buffer containing 0.18% glucose and either vehicle or the indicated drugs/times. All uptake conditions contained 100 nM desipramine to eliminate DA uptake by the endogenous NE transporter. Uptake was initiated by addition of 1 µM [3H]DA, proceeded for 10 min, and was terminated by rapidly washing three times with ice-cold KRH buffer. Non-specific uptake was defined in the presence of 10 µM GBR12935. Cells were solubilized in liquid scintillant, and accumulated radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting in a Wallac Microbeta scintillation plate reader (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA).

Cell-surface biotinylation

Cells were washed with and incubated in PBS2+/BSA/glucose (PBS supplemented with 1.0 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.2% bovine serum albumin, 0.18% glucose) ± 1 µM PMA for 30 min at 37 °C. Incubation was rapidly stopped by placing cells on ice and washing them with ice-cold PBS2+. Cells were surface biotinylated with 1.0 mg/ml sulfo NHS-SS-biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL) as described previously (Loder and Melikian, 2003; Holton et al., 2005). Cells were subsequently washed in PBS2+ and lysed in RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1.0% Triton X-100, and 1.0% sodium deoxycholate) with protease inhibitors (1.0 mM PMSF, 1.0 µg/ml aprotinin, 1.0 µg/ml pepstatin, and 1.0 µg/ml leupeptin). Protein concentrations were determined using the BSA protein assay kit (Pierce). Biotinylated and non-biotinylated proteins were separated by streptavidin affinity chromatography from equivalent amounts of cellular proteins, and samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot. Immunoreactive bands were detected with SuperSignal West Dura Extended substrate (Pierce). Non-saturating, immunoreactive bands were captured using a CCD camera gel documentation system and bands in the liner range of detection were quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Internalization assay

Relative endocytic rates over an initial 10 minute internalization time were measured using reversible surface biotinylation as previously described (Loder and Melikian, 2003; Holton et al., 2005). Briefly, cells were surface biotinylated with 2.5 mg/ml sulfo NHS-SS-biotin. To initiate endocytosis, cells were repeatedly washed with prewarmed PBS2+/BSA/glucose and incubated in the same solution for 10 min at 37 °C. Endocytosis was rapidly stopped by placing cells on ice and washing them with ice-cold NT Buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2% bovine serum albumin, 20 mM Tris, pH 8.6). Residual surface biotin was stripped by reducing surface disulfide bonds in freshly prepared 50 mM TCEP (Pierce) in NT buffer, 20 min, 4°C × 2. Strip efficiencies were determined for each experiment on biotinylated cells kept in parallel at 4 °C and averaged >90%. Cells were subsequently lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors, and biotinylated proteins were isolated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot as described above. Internalization was measured as the %DAT biotinylated (internalized) compared to control samples kept in parallel at 4°C.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. William Kobertz, Mary Munson, Paul Gardner and Andrew Tapper for helpful and insightful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grant #DA15169 to H.E.M.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Amara SG, Sonders MS. Neurotransmitter transporters as molecular targets for addictive drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerggaard C, Fog JU, Hastrup H, Madsen K, Loland CJ, Javitch JA, Gether U. Surface targeting of the dopamine transporter involves discrete epitopes in the distal C terminus but does not require canonical PDZ domain interactions. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7024–7036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1863-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudanova E, Navaroli DM, Melikian HE. Amphetamine-induced decreases in dopamine transporter surface expression are protein kinase C-independent. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DJ. Functional imaging studies on dopamine and motor control. J Neural Transm. 2001;108:1283–1298. doi: 10.1007/s007020100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson T, Bjorklund T, Kirik D. Restoration of the Striatal Dopamine Synthesis for Parkinsons Disease:Viral Vector-Mediated Enzyme Replacement Strategy. Current Gene Therapy. 2007;7:109–120. doi: 10.2174/156652307780363125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro AM, Blakely RD. Serotonin-, protein kinase C-, and Hic-5-associated redistribution of the platelet serotonin transporter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24769–24780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603877200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro AM, Ingram SL, Beaulieu J-M, Sweeney A, Amara SG, Thomas SM, Caron MG, Torres GE. The Multiple LIM Domain-Containing Adaptor Protein Hic-5 Synaptically Colocalizes and Interacts with the Dopamine Transporter. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7045–7054. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07045.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen NH, Reith ME, Quick MW. Synaptic uptake and beyond: the sodium- and chloride-dependent neurotransmitter transporter family SLC6. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:519–531. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Tilley MR, Wei H, Zhou F, Zhou FM, Ching S, Quan N, Stephens RL, Hill ER, Nottoli T, Han DD, Gu HH. Abolished cocaine reward in mice with a cocaine-insensitive dopamine transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9333–9338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600905103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira IR, Juruena MF. Treatment of psychosis: 30 years of progress. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2006;31:523–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2006.00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhan H, Reiterer V, Korkhov VM, Schmid JA, Freissmuth M, Sitte HH. Concentrative export from the endoplasmic reticulum of the gamma-aminobutyric acid transporter 1 requires binding to SEC24D. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7679–7689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609720200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fog JU, Khoshbouei H, Holy M, Owens WA, Vaegter CB, Sen N, Nikandrova Y, Bowton E, McMahon DG, Colbran RJ, Daws LC, Sitte HH, Javitch JA, Galli A, Gether U. Calmodulin kinase II interacts with the dopamine transporter C terminus to regulate amphetamine-induced reverse transport. Neuron. 2006;51:417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gether U, Andersen PH, Larsson OM, Schousboe A. Neurotransmitter transporters: molecular function of important drug targets. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2006;27:375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giros B, Jaber M, Jones SR, Wightman RM, Caron MG. Hyperlocomotion and indifference to cocaine and amphetamine in mice lacking the dopamine transporter. Nature. 1996;379:606–612. doi: 10.1038/379606a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granas C, Ferrer J, Loland CJ, Javitch JA, Gether U. N-terminal Truncation of the Dopamine Transporter Abolishes Phorbol Ester- and Substance P Receptor-stimulated Phosphorylation without Impairing Transporter Internalization. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4990–5000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holton KL, Loder MK, Melikian HE. Nonclassical, distinct endocytic signals dictate constitutive and PKC-regulated neurotransmitter transporter internalization. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:881–888. doi: 10.1038/nn1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. NEURAL MECHANISMS OF ADDICTION: The Role of Reward-Related Learning and Memory. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2006;29:565–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SR, Gainetdinov RR, Jaber M, Giros B, Wightman RM, Caron MG. Profound neuronal plasticity in response to inactivation of the dopamine transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4029–4034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LB, Chen N, Ramamoorthy S, Chi L, Cui XN, Wang LC, Reith ME. The role of N-glycosylation in function and surface trafficking of the human dopamine transporter. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21012–21020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loder MK, Melikian HE. The dopamine transporter constitutively internalizes and recycles in a protein kinase C-regulated manner in stably transfected PC12 cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22168–22174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301845200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melikian HE. Neurotransmitter transporter trafficking: endocytosis, recycling, and regulation. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;104:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melikian HE, Buckley KM. Membrane trafficking regulates the activity of the human dopamine transporter. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7699–7710. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-07699.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda M, Dionne KR, Sorkina T, Sorkin A. Three ubiquitin conjugation sites in the amino terminus of the dopamine transporter mediate protein kinase C-dependent endocytosis of the transporter. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:313–323. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda M, Wu CC, Sorkina T, Korstjens DR, Sorkin A. Enhanced ubiquitylation and accelerated degradation of the dopamine transporter mediated by protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35617–35624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506618200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Is there a common molecular pathway for addiction? Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1445–1449. doi: 10.1038/nn1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MB. Regulated trafficking of neurotransmitter transporters: common notes but different melodies. J Neurochem. 2002;80:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH. Monoamine transporters and psychostimulant drugs. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;479:23–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyon SP, Carroll FI. Dopamine Transporter Ligands: Recent Developments and Therapeutic Potential. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;6:1825–1843. doi: 10.2174/156802606778249775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid JA, Scholze P, Kudlacek O, Freissmuth M, Singer EA, Sitte HH. Oligomerization of the human serotonin transporter and of the rat GABA transporter 1 visualized by fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy in living cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3805–3810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholze P, Freissmuth M, Sitte HH. Mutations within an Intramembrane Leucine Heptad Repeat Disrupt Oligomer Formation of the Rat GABA Transporter 1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:43682–43690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkina T, Hoover BR, Zahniser NR, Sorkin A. Constitutive and protein kinase C-induced internalization of the dopamine transporter is mediated by a clathrin-dependent mechanism. Traffic. 2005;6:157–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkina T, Doolen S, Galperin E, Zahniser NR, Sorkin A. Oligomerization of dopamine transporters visualized in living cells by fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28274–28283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkina T, Miranda M, Dionne KR, Hoover BR, Zahniser NR, Sorkin A. RNA Interference Screen Reveals an Essential Role of Nedd4-2 in Dopamine Transporter Ubiquitination and Endocytosis. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8195–8205. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1301-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GE, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Plasma membrane monoamine transporters: structure, regulation and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003a;4:13–25. doi: 10.1038/nrn1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GE, Carneiro A, Seamans K, Fiorentini C, Sweeney A, Yao W-D, Caron MG. Oligomerization and Trafficking of the Human Dopamine Transporter. MUTATIONAL ANALYSIS IDENTIFIES CRITICAL DOMAINS IMPORTANT FOR THE FUNCTIONAL EXPRESSION OF THE TRANSPORTER. J Biol Chem. 2003b;278:2731–2739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GE, Yao WD, Mohn AR, Quan H, Kim KM, Levey AI, Staudinger J, Caron MG. Functional interaction between monoamine plasma membrane transporters and the synaptic PDZ domain-containing protein PICK1. Neuron. 2001;30:121–134. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Addictive drugs and brain stimulation reward. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:319–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita A, Singh SK, Kawate T, Jin Y, Gouaux E. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporters. 2005;437:215–223. doi: 10.1038/nature03978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahniser NR, Doolen S. Chronic and acute regulation of Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporters: drugs, substrates, presynaptic receptors, and signaling systems. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2001;92:21–55. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SJ, Kavanaugh MP, Sonders MS, Amara SG, Zahniser NR. Activation of protein kinase C inhibits uptake, currents and binding associated with the human dopamine transporter expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:1358–1365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang X, Oosting RS, Jones SR, Gainetdinov RR, Miller GW, Caron MG, Hen R. Hyperactivity and impaired response habituation in hyperdopaminergic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1982–1987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]