Abstract

Accumulating evidence suggests the endocannabinoid system modulates environmental cues’ ability to induce seeking of drugs, including nicotine and alcohol. However, little attention has been directed toward extending these advances to the growing problem of cannabis-use disorders. Therefore, we studied intravenous self-administration of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive constituent of marijuana, using a second-order schedule of drug seeking. Squirrel monkeys’ lever responses produced only a brief cue light until the end of the session, when the final response delivered THC along with the cue. When a reinstatement procedure was used to model relapse following a period of abstinence, THC-seeking behavior was robustly reinstated by the cue or by pre-session administration of THC, other cannabinoid agonists, or morphine, but not cocaine. The cannabinoid antagonist rimonabant blocked cue-induced drug seeking, THC-induced drug seeking, and the direct reinforcing effects of THC. Thus, rimonabant and related medications might be effective as treatments for cannabinoid dependence.

Keywords: cannabinoids, drug seeking, reinstatement, rimonabant, second-order schedule, self-administration

INTRODUCTION

Cannabinoid research is currently one of the most active areas of neuroscience, largely because drugs acting on the cannabinoid system may be beneficial for treating a wide variety of disorders, including substance abuse. This system appears to be capable of modulating the rewarding effects of many drugs of abuse, including opioids (De Vries et al, 2003; Navarro et al, 2001; Solinas et al, 2003), nicotine (Cohen et al, 2002; Le Foll and Goldberg, 2005) and alcohol (De Vries and Schoffelmeer, 2005; Economidou et al, 2006). Ironically, little attention has been focused on potential pharmacotherapies specifically targeting the substantial and growing problem of cannabis use disorders (Compton et al, 2004). General population household survey data showed that annual prevalence of cannabis use in the USA in 2006 was 10.3% of the population (compared with 2.5% for cocaine) and 1.2 million people reported receiving treatment for cannabis use (compared with 928,000 for cocaine) (SAMHSA, 2007). Moreover, primary cannabis admissions are on the rise. For example, in New York City, the primary cannabis admissions to all treatment programs increased from less than 5% in 1991, to 24.3% in 2003, and to 27.8% in 2006 (CEWG, 2004; CEWG, 2007). In the past, one obstacle to finding new pharmacotherapies has been the lack of animal models of cannabis abuse (Justinova et al, 2005a). However, we have recently developed procedures for establishing robust self-administration of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC, the main psychoactive constituent of marijuana) and other cannabinoid agonists in squirrel monkeys (Justinova et al, 2003; Justinova et al, 2004; Justinova et al, 2005b; Tanda et al, 2000).

An advantage of drug self-administration as an animal model of human drug abuse is that it can be modified in various ways to concentrate on specific components of drug abuse (Panlilio and Goldberg, 2007). One particular type of self-administration procedure, the second-order schedule (Goldberg et al, 1975; Schindler et al, 2002), has been strongly advocated as the most advantageous animal model of drug-seeking behavior (Arroyo et al, 1998; Everitt and Robbins, 2000). This drug-seeking schedule has many advantages related to its incorporation of drug-related stimuli, which model the environmental cues that can maintain drug seeking and induce drug craving and relapse in humans. Thus, this procedure makes it possible to evaluate treatments that target drug seeking, per se, in a drug-free state, as opposed to treatments that only block the effects of a drug after it has been taken. This is important because treatments that reduce drug seeking might provide an especially effective means of achieving and maintaining drug abstinence. The second-order drug-seeking schedule can also be used to study relapse induced by drug-related cues, as well as relapse caused by re-exposure to the abused drug or exposure to other drugs (Spealman et al, 1999). Relapse is one of the defining features of addiction, and perhaps the most important impediment to effective treatment (O’Brien, 2001).

In the present study, we provide the first demonstration of THC self-administration utilizing this drug-seeking procedure. Under this procedure, squirrel monkeys’ drug-seeking behavior (lever-pressing) intermittently produced only brief presentations of a visual stimulus, until the end of the 30 minute session, when the last response of the session produced both the stimulus and an the intravenous delivery of THC. Thus, all drug-seeking behavior occurred prior to drug delivery, and — unlike other self-administration procedures — this behavior was not influenced by other pharmacological effects of the drug, such as behavioral stimulation or depression. Importantly, the behavior was influenced by the drug-paired stimulus (cue), which is intended to model the effects of drug-associated environmental stimuli that may maintain drug seeking in humans. Thus, it was possible to study the effects of potential treatment drugs specifically on THC seeking. The drug-seeking procedure was also used to model cue-induced relapse by measuring the ability of the drug-paired stimulus to reinstate drug seeking after a period of abstinence from THC. The ability of THC, several other cannabinoid drugs, cocaine and morphine to reinstate drug seeking was also studied, as was the ability of the potential treatment drugs rimonabant (SR141716A, a cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist) and naltrexone (an opioid antagonist) to block this drug-induced reinstatement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Male squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) weighing 0.8 to 1.2 kg were housed in individual cages in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room with unrestricted access to water. Monkeys were fed (~2 hours after the session) 5 biscuits of high protein monkey diet (Lab Diet 5045, PMI Nutrition International, Richmond, Indiana) and 2 pieces of Banana Softies (Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ) to maintain their body weights at a stable level throughout the study. Fresh fruit, vegetables and environmental enrichment were also provided daily. The facilities are fully accredited by AAALAC, and experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the NIDA Intramural Research Program and conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (National Research Council 2004). Five monkeys (23–90, 5–91, 1551, 1577 and 1584) were used in these experiments. Two monkeys (23–90 and 5–91) had previous experience self-administering i.v. amphetamine under the second-order schedule, and the other three had experience with fixed-ratio schedules of cocaine self-administration (1577 and 1584) or food reinforcement (1551). Prior to training with the second-order drug-seeking procedure, all monkeys had prior experience with extinction (non-reinforcement), including 10 sessions immediately before the start of THC self-administration training.

Apparatus

Experimental chambers were previously described in detail (Justinova et al, 2003). The sound-attenuating isolation chambers were equipped with a white house light and white noise for masking of external sound and contained a Plexiglas chair. The chair had a response lever mounted on a transparent front wall and pairs of green and amber stimulus lights, mounted behind the transparent wall of the chair, which could be illuminated and used as visual stimuli. Monkeys were prepared with chronic indwelling venous catheters (polyvinyl chloride), as described previously (Goldberg, 1973). The monkey’s catheter was connected to polyethylene tubing, which passed out of the isolation chamber and attached to a motor-driven syringe pump. Before the start of each session, monkeys were placed into chairs and lightly restrained in the seated position by waist locks.

Drug-seeking procedure

Under the drug-seeking schedule, a green light was presented, and every 10th lever-press during a 30-minute fixed-interval of time (FI 30′) changed the green light to amber (the brief stimulus) for 2 s (10-response fixed-ratio schedule of reinforcement; FR 10). The first FR 10 completed after the 30-min fixed-interval elapsed produced ten consecutive injections of THC (0.2 ml delivered over 0.2 s, with 10 s between injections), each paired with a 2-s presentation of the amber light. In standard nomenclature (Schindler et al, 2002), this was a FI 30′ (FR 10: S) schedule. THC administration occurred only at the end of each daily session (Monday to Friday). Drug seeking was shaped under the second-order schedule by slowly increasing the length of the FI [from FI 2′ (FR 10: S) to FI 30′ (FR 10: S)]. Sessions typically lasted about 32 minutes, and after the FI elapsed, adequate time (up to 30 min) was always allowed for completion of the final FR and drug delivery. THC injection doses of 1, 2, 4 and 8 μg/kg were used to give total end-of-session doses of 10, 20, 40 and 80 μg/kg, respectively. Each of these doses of THC was tested for 9–10 consecutive sessions, preceded by 9–10 sessions in which vehicle was delivered at the end of the session instead of THC (extinction).

The effects of pre-session intramuscular (IM) treatment with rimonabant were determined using the following procedure, in which THC (40 μg/kg) was delivered at the end of each session. First, vehicle was administered IM 60 min before each of at least 10 consecutive sessions. Then 0.3 mg/kg of rimonabant was administered IM 60 min before each session for 10 consecutive sessions. Finally, IM vehicle injections were administered before each session for 10 sessions. After testing with rimonabant, a similar procedure was used with pre-session injections of naltrexone (0.1 mg/kg IM), given 15 min before the session.

The effects of brief-stimulus presentations were assessed by discontinuing the stimulus (but still delivering end-of session THC) for 10 sessions. These no-stimulus test sessions were preceded by 10 sessions in which brief stimuli were presented and THC (40 μg/kg) was delivered at the end of each session. (Brief stimulus presentations were only discontinued during the 30-minute drug seeking period; the stimulus always accompanied the 10 end-of session i.v. injections.)

Cue-induced reinstatement was studied by first discontinuing both the brief stimulus and THC delivery for 5–10 sessions, then reintroducing the stimulus during a test session. Test sessions for cue-induced reinstatement were each separated by two to three intervening sessions without the stimulus. No end-of-session THC was delivered during these test sessions or intervening sessions. The procedure used to test for drug-induced reinstatement was similar, except brief stimulus presentations and end-of-session THC delivery were discontinued during the test session and at least two preceding sessions, and THC (10–80 μg/kg), morphine (0.19–1.50 mg/kg), anandamide (30–560 μg/kg), methanandamide (3–100 μg/kg), AM404 (0.3–3 mg/kg) or cocaine (0.03–1.0 mg/kg) were administered i.v. by the experimenter immediately before the start of the test session. The ability of an opioid antagonist (naltrexone; 0.1 mg/kg, given IM 15 min before the session) or cannabinoid antagonist (rimonabant; 0.3 mg/kg, given IM 60 min before the session) to block reinstatement induced by THC (40 μg/kg) or morphine (0.75 mg/kg) was also tested.

Drugs

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; Research Triangle, NIH), anandamide (N-Arachidonylethanolamide; Tocris Cookson, USA), methanandamide (Tocris Cookson, USA) and AM404 (Tocris Cookson, USA) were dissolved in a vehicle containing 0.125% – 4% ethanol and 0.125% – 4% Tween 80 and saline. Rimonabant (SR141716; Research Triangle, NIH) was dissolved in a vehicle containing 1% ethanol and 1% Tween 80 and saline. (−)-Cocaine HCl (Sigma, USA), naltrexone HCl (Sigma, USA) and morphine sulfate (NIH) were dissolved in saline.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed on the total number of THC-seeking responses per session. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. For the THC dose-response function (Fig. 1), the last three sessions for each subject under each dose were averaged. Statistical analysis was done using single-factor repeated measures ANOVA (data met the assumptions of the test) to assess differences between vehicle and test-drug pretreatment conditions or between different doses of THC and vehicle, as well as between different doses of drugs and vehicle during reinstatement experiments. Paired comparisons were performed using Dunnett’s or Bonferroni procedures. Statistical significance was accepted at the P < 0.05 level. SigmaStat software (http://www.systat.com) was used for all statistical analyses.

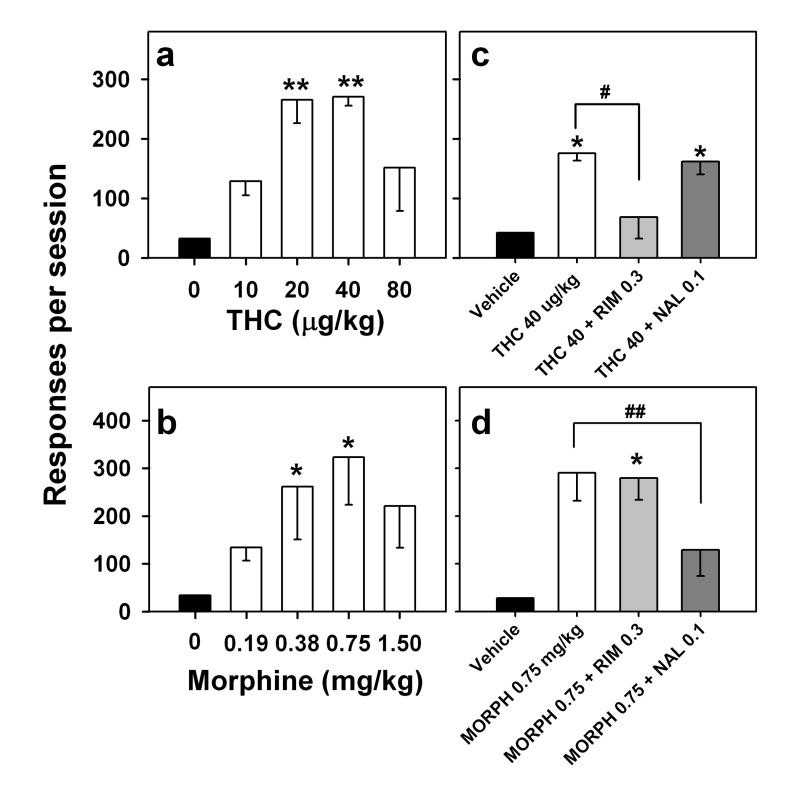

Figure 1.

THC dose-effect function (a). Number of responses per session is shown as a function of dose of THC under a second-order schedule of THC seeking, in which each 10th response produced a brief presentation of a visual stimulus. Each symbol represents the mean ± S.E.M. of the last three sessions within the block of 10 sessions in which each dose of THC or vehicle was tested (n = 5). **P < 0.01, post-hoc comparisons with vehicle self-administration (ANOVA, Dunnett’s test). Vehicle extinction (b). Number of THC-seeking responses per session during consecutive sessions before, during and after nine sessions in which vehicle injections were substituted for end-of-session THC injections. Each point represents the mean ± S.E.M. for 5 monkeys. **P < 0.01, post-hoc comparisons with session 4, the last THC session before vehicle extinction (ANOVA, Dunnett’s test).

RESULTS

THC seeking under the second-order schedule

Drug seeking under the second-order schedule (Fig. 1a) was dose dependent (F4,16 = 14.82, p < 0.001), with THC doses of 20, 40, and 80 μg/kg, but not 10 μg/kg, maintaining significantly more responding than vehicle. The dose-effect function had an inverted-U shape, with the highest level of drug seeking occurring when the end-of-session dose of THC was 40 μg/kg.

When vehicle was substituted for 40 μg/kg of THC (Fig. 1b), drug seeking was significantly decreased starting the second session (session 6 on the figure) and continued to occur at a low rate during the sessions that followed (F9,36 = 7.73, P < 0.001). When end-of-session delivery of THC was resumed, THC seeking stayed low during the first session (session 14 on the figure), increased substantially in the next session and returned to baseline levels within three sessions (F5,19 = 6.60, P = 0.001).

Effects of the cannabinoid receptor antagonist rimonabant and the opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone on THC seeking

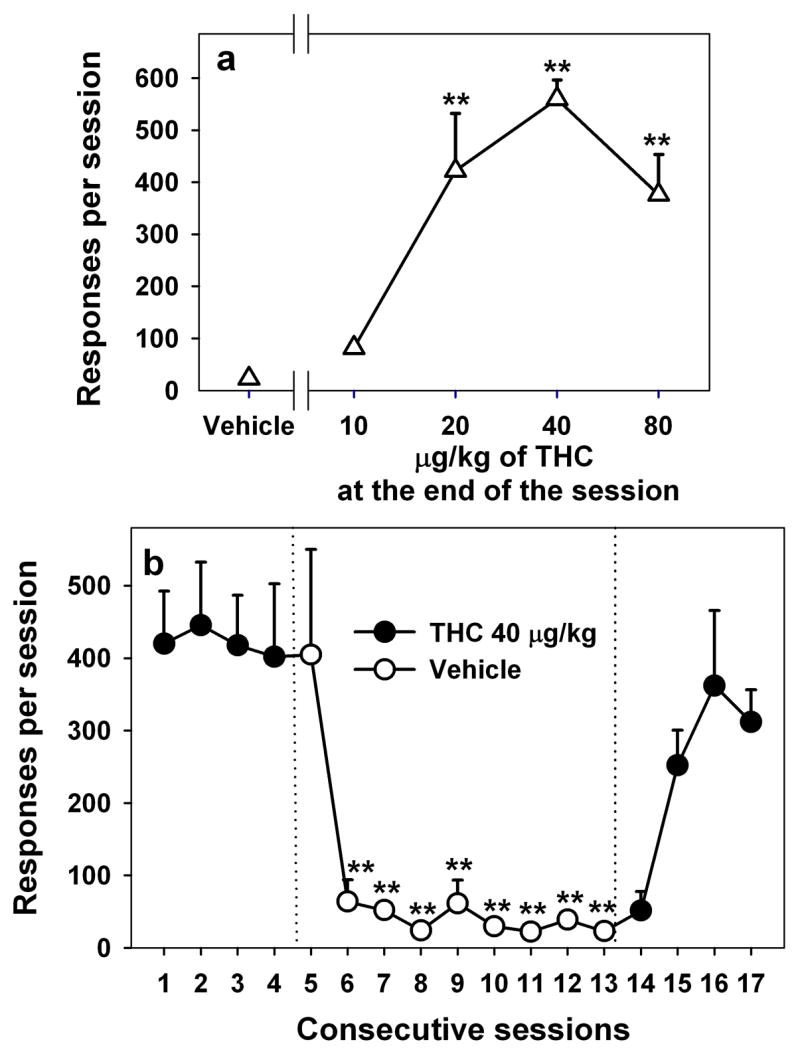

The cannabinoid antagonist, rimonabant (0.3 mg/kg), which earlier was found to block drug taking under a simple fixed-ratio schedule of THC self-administration (Tanda et al, 2000), significantly decreased THC seeking under the second-order schedule in the present study (F10,30 = 10.45, P < 0.001; Fig. 2a). This decrease was significant starting with the first session of rimonabant treatment and remained significant throughout the 10-day course of treatment, during which the average level of responding was 78% lower than baseline. Pretreatment with the opioid antagonist, naltrexone (0.1 mg/kg), also decreased THC seeking (F9,18 = 2.82, P = 0.029; Fig. 2b). Although naltrexone, like rimonabant, decreased THC seeking in the first two sessions, this effect became weaker during the next 7 sessions of naltrexone treatment, during which the average level of THC seeking was 42% lower than baseline. When treatment with either rimonabant or naltrexone ended, THC seeking gradually resumed over 2–3 sessions.

Figure 2.

Effects of pretreatment with the selective cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant (a) and opioid antagonist naltrexone (b) on THC-seeking behavior. A dose of 0.3 mg/kg rimonabant was given IM 60 minutes before each of ten consecutive sessions, or a dose of 0.1 mg/kg naltrexone was given IM 15 minutes before each of nine consecutive sessions. Each point represents the mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, post-hoc comparisons with the last THC session with vehicle pretreatment (session 4) (ANOVA, Dunnett’s test).

Effects of omitting brief-stimulus presentations

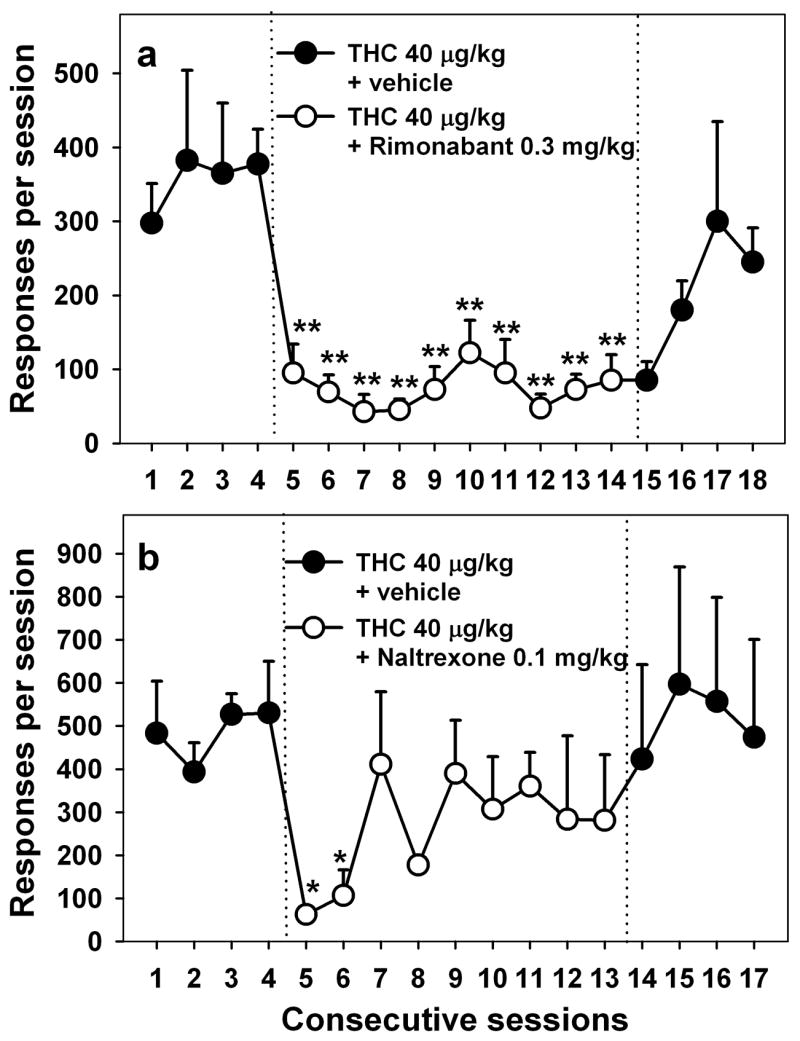

Although brief-stimulus presentations alone did not maintain responding when end-of-session THC delivery was discontinued for repeated sessions (as seen in Fig. 1b), the brief stimulus nonetheless played a critical role in maintaining the high rates of drug seeking seen under baseline conditions (i.e., when both the stimulus and end-of-session THC were presented). This contribution is clear from the results obtained when brief stimulus presentation was discontinued but end-of-session THC was still delivered. Under these conditions, there was an 85% decrease in THC seeking compared to baseline (F10,30 = 21.31, P = 0.029; Fig. 3a). This decrease was significant starting with the first session without the brief stimulus. Even though THC continued to be delivered at the end of each session for 10 days, THC seeking showed no sign of recovering until the brief-stimulus presentations were resumed, at which point THC seeking immediately recovered (F5,15 = 7.58, P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Effects of omitting brief-stimulus presentations under the THC-seeking schedule (a). Circles represent the mean number of responses per session (n = 4) before, during and after each of ten sessions in which brief stimuli were not presented during the session, although the 10 end-of-session THC injections were always paired with the stimulus. **P < 0.01, post-hoc comparisons with the last THC session (session 4) with brief stimulus present (ANOVA, Dunnett’s test). Cue-induced reinstatement (b). Stimulus presentation and end-of-session delivery of THC were discontinued until THC seeking only occurred at low levels (black bars represent average responding on a day immediately preceding a reinstatement test). Then, brief-stimulus presentations were resumed during three test sessions (white bars) separated by two to three sessions with no brief-stimulus presentations. Each bar represents an average from four monkeys. *P < 0.05, paired comparisons with a respective day before each test (ANOVA, Bonferroni test). Effect of daily pretreatment with rimonabant (0.3 mg/kg) on cue-induced reinstatement (c). White bars represent an average (n = 3) of all reinstatement tests with brief stimulus present either after pretreatment with vehicle or rimonabant. Black bars represent average (n = 3) responding on days immediately preceding a reinstatement test. *P < 0.05, paired comparisons with a respective day before the reinstatement test (ANOVA, Bonferroni test).

Cue-induced reinstatement of THC seeking

When both the brief stimulus and THC delivery were simultaneously discontinued, THC seeking occurred at very low levels (Fig. 3b). However, after repeated sessions in which no brief stimuli were presented, reintroduction of the brief stimulus dramatically reinstated THC seeking. This sequence — two to three sessions with no stimulus and no THC, followed by reintroduction of the brief stimulus (but not end-of-session THC) during a test session — was repeated three times in each monkey, and the cue continued to reinstate THC seeking (1st test: F1,3 = 24.51, P = 0.016; 2nd test: F1,3 = 11.23, P = 0.044; 3rd test: F1,3 = 12.54, P = 0.038).

When the monkeys received a daily pretreatment with rimonabant (0.3 mg/kg) for nine to ten consecutive sessions while brief stimulus and THC delivery were discontinued, the reintroduction of brief-stimulus presentations failed to reinstate THC seeking (Fig. 3c; F1,2 = 3.19, P = 0.22). The testing sequence consisted of several days with no stimulus and no THC, followed by reintroduction of the brief-stimulus (but no THC) during the test session. The sequence was repeated one to three times in each monkey, and figure 3c shows averaged data for all three monkeys. The testing sequence with vehicle pretreatment was performed within four weeks of the rimonabant testing and shows that brief-stimulus presentations (repeated three times in each monkey), in the absence of rimonabant, continued to significantly reinstate THC seeking (Fig. 3c; F1,2 = 23.16, P = 0.04).

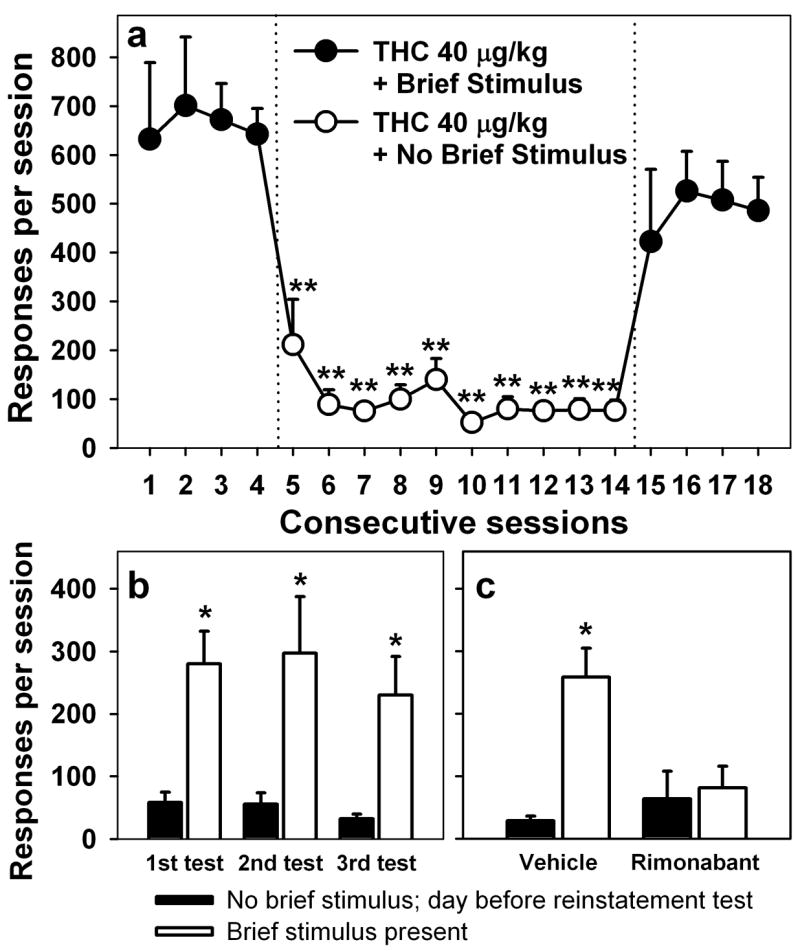

Drug-induced reinstatement of THC seeking by THC and morphine

The effects of pre-session priming injections with THC and morphine were also studied during a phase in which brief stimuli and end-of-session THC delivery were discontinued. THC seeking was robustly reinstated in a dose dependent fashion by pre-session treatment with 20 or 40 μg/kg THC (F4,16 = 18.08, P < 0.001, Fig. 4a), but not by the lowest dose (10 μg/kg) or the highest dose (80 μg/kg, which may have had satiating or behaviorally disruptive effects). Morphine dose-dependently reinstated THC seeking, with the 0.75 mg/kg dose of morphine producing the strongest effect (F4,8 = 4.65, p = 0.031; Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

Drug-induced reinstatement. Effects of passive intravenous exposure to different doses of THC (a) and morphine (b) on THC seeking during sessions in which the brief stimulus was not presented and end-of-session THC was not delivered. Each bar represents mean ± S.E.M. of number of responses per session from five (THC) or three (morphine) monkeys. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, post-hoc comparisons with vehicle extinction (dose 0 mg/kg) (ANOVA, Dunnett’s test). Effects of a cannabinoid antagonist and an opioid antagonist on THC- (c) and morphine-induced (d) reinstatement of THC seeking. Rimonabant (RIM; IM, 60 min before session) or naltrexone (NAL; IM, 15 min before the session) was injected, and then THC or morphine (MORPH) was injected i.v. immediately before the session. The brief stimulus was not presented and end-of-session THC was not delivered. Each bar represents mean ± S.E.M. of number of responses per session from three monkeys. *P < 0.05, paired comparisons with vehicle; # P < 0.05, paired comparisons with THC reinstatement; ## P < 0.01, paired comparisons with morphine reinstatement (ANOVA, Bonferroni test).

Blockade of THC- and morphine-induced reinstatement

The ability of a cannabinoid antagonist (rimonabant, 0.3 mg/kg) and an opioid antagonist (naltrexone, 0.1 mg/kg) to alter the reinstatement induced by pre-session injections of THC (40 μg/kg) or morphine (0.75 mg/kg) was also tested (Fig. 4). Rimonabant blocked THC-induced reinstatement (Fig. 4c; F1,2 = 20.27, P = 0.046, paired comparisons with THC 40 μg/kg) but not morphine-induced reinstatement (Fig. 4d; F1,2 = 0.03, P = 0.88, paired comparisons with morphine 0.75 mg/kg; F1,2 = 26.90, P = 0.035, paired comparisons with vehicle). Naltrexone blocked morphine-induced reinstatement (Fig. 4d; F1,2 = 273.84, P = 0.004, paired comparisons with morphine 0.75 mg/kg), but failed to affect THC-induced reinstatement (Fig. 4c; F1,2 = 2.03, P = 0.29, paired comparisons with THC 40 μg/kg; F1,2 = 19.31, P = 0.048, paired comparisons with vehicle).

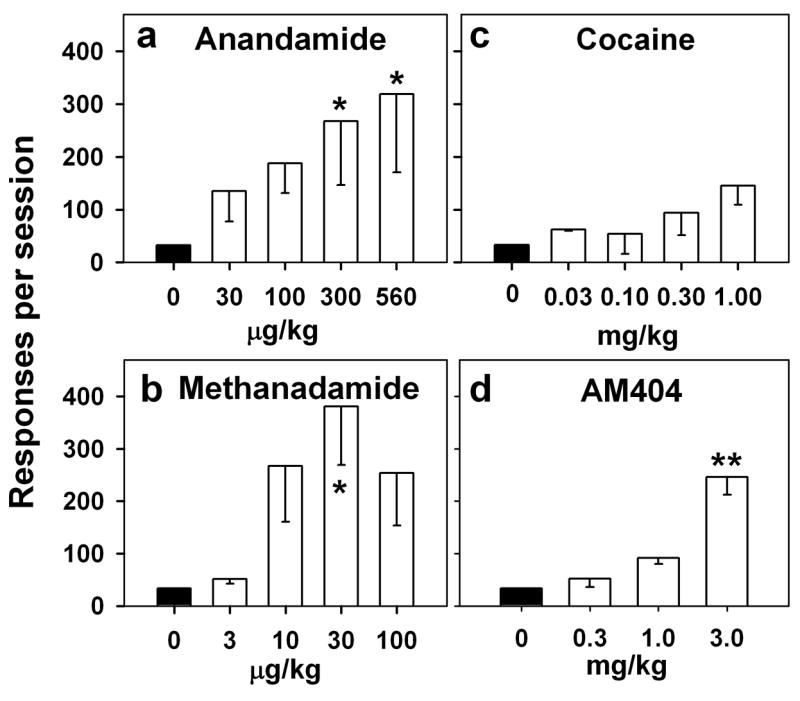

Reinstatement by other drugs

Pre-session injections of other drugs of abuse like the psychostimulant cocaine, other cannabinoid agonists (anandamide and methanandamide), and an anandamide transport inhibitor (AM404) were also tested for their ability to reinstate THC seeking. The test sequence was the same as that described above. Over a wide range of doses, cocaine (0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1.00 mg/kg) failed to reinstate THC seeking (F4,8 = 1.81, p = 0.22; Figure 5c). Pre-session treatment with the endogenous cannabinoid agonist, anandamide (F4,8 = 4.43, p = 0.035; Figure 5a), or its longer-acting congener, methanandamide (F4,8 = 4.05, p = 0.044; Figure 5b), produced dose-dependent reinstatement of THC seeking. AM404 (0.3, 1 and 3 mg/kg) also produced significant reinstatement, but only at the highest dose tested (F3,6 = 18.19, p = 0.002; Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Drug-induced reinstatement. Effects of passive intravenous exposure (immediately before the session) to cocaine (c), anandamide (a), methanandamide (b), and AM404 (d) on THC seeking during sessions in which the brief stimulus was not presented and end-of-session THC was not delivered. Each bar represents mean ± S.E.M. of number of responses per session from three monkeys. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, post-hoc comparisons with vehicle extinction (dose 0 mg/kg) (ANOVA, Dunnett’s test).

DISCUSSION

Monkeys’ THC-seeking behavior occurred at a high rate even though the drug was not delivered until the end of the session. This behavior depended on both the delivery of THC and response-contingent presentations of the drug-paired stimulus, which is intended to model the effects of environmental cues in the human drug-abuse environment. When the stimulus was not presented, THC seeking decreased abruptly and continued to occur at a low rate even when THC was still delivered at the end of each session. Moreover, in the relapse procedure, when the stimulus and THC delivery were both discontinued, restoring just the stimulus caused the monkeys to immediately resume THC seeking. Thus, like re-exposure to the drug, re-exposure to THC-associated cues represents an important trigger for relapse following a period of abstinence.

However, high levels of THC seeking were only maintained over repeated sessions when the cues were presented and a reinforcing dose of THC was delivered at the end of the previous session. Neither vehicle nor a low dose (10 μg/kg) of THC maintained responding over repeated days, even when the cues continued to be presented. Although response-contingent cues can sometimes maintain drug-seeking behavior for many sessions in the absence of drug delivery (Schindler et al, 2002), this is not always the case, particularly in subjects with previous exposure to extinction procedures. Thus, the decrease in drug seeking when end-of-session THC delivery was discontinued but the cue was still presented is not a unique effect associated with cannabinoid seeking; this effect was similar to that observed under similar schedules of cocaine- or food-seeking (Goldberg and Tang, 1977) and can be attributed to the monkeys of the present study having had extensive experience with extinction.

When the THC-seeking procedure was used to evaluate the effects of potential therapeutic treatments, it was found that the cannabinoid CB1-receptor antagonist, rimonabant, was highly effective in reducing the drug-seeking response. Importantly, treatment with rimonabant produced an immediate decrease in THC seeking, indicating that rimonabant blocked the ability of the stimulus to maintain THC seeking. This effect cannot be attributed to non-specific reductions of response rate since the rimonabant dose 0.3 mg/kg was well below doses that disrupt behavior in squirrel monkeys (3.2 mg/kg; Nakamura-Palacios et al, 2000). This finding is consistent with a number of studies showing that rimonabant can reduce the behavioral effects of stimuli associated with other drugs of abuse, including nicotine, alcohol, cocaine, and heroin (Cohen et al, 2005; De Vries and Schoffelmeer, 2005; Fattore et al, 2007a; Le Foll and Goldberg, 2005; Maldonado et al, 2006), as well as the effects of similar cues under second-order food-seeking procedures (Evenden and Ko, 2007; Thornton-Jones et al, 2005). Thus, this effect of rimonabant on responding maintained by drug-paired cues appears to be a general effect, unlike its ability to reduce drug-taking behavior, which seems to be limited to specific drugs (De Vries and Schoffelmeer, 2005). This suggests that the ability to block both drug seeking (behavior reinforced by drug-related cues) and drug taking (behavior reinforced directly by the drug) (Tanda et al, 2000) might make rimonabant and similar drugs especially useful for treating cannabinoid use disorders.

In contrast with rimonabant, treatment with the opioid antagonist, naltrexone, had a more limited effect. In a previous study of (Justinova et al, 2004), naltrexone produced a partial reduction (about 40%) in THC taking over most of a five-day course of treatment. However, in the present study, naltrexone only decreased THC seeking during the first two days of treatment. These results might suggest that, like rimonabant, naltrexone can alter both THC seeking and THC taking, but that naltrexone only partially blocks the reinforcing effects of THC. This finding is consistent with the many studies showing functional interactions between the cannabinoid and opioid systems, but it appears that an opioid antagonist alone might not provide significant protection against drug seeking induced by THC-related environmental cues.

The results of this study demonstrate that this second-order schedule can be used to study not only THC seeking behavior but both drug- and cue-induced reinstatement of THC seeking. In this model of relapse, we found that drug seeking was reinstated when the monkeys were passively exposed to THC, the endocannabinoid anandamide, or its longer-acting congener, methanandamide. Reinstatement was also produced by the anandamide transport inhibitor, AM404, which has been shown to increase brain levels of endogenous anandamide in rodents (Bortolato et al, 2006). Also, consistent with evidence for functional links between the cannabinoid and opioid systems (De Vries et al, 2003; Fattore et al, 2007b), passive exposure to morphine increased THC seeking after a period of abstinence. Although it has been shown that passive cannabinoid exposure can reinstate cocaine seeking in rats (De Vries et al, 2001; Xi et al, 2006), cocaine did not reinstate THC seeking, even though these monkeys had a history of psychostimulant self-administration. This finding is consistent with those of Spano et al (2004), who found that the cannabinoid agonist, WIN 55,212-2, or heroin, reinstated seeking of WIN 55,212-2 in rats, but cocaine did not.

When we tested the ability of rimonabant and naltrexone to block the reinstating effects of passive exposure to THC or morphine, we found that the cannabinoid antagonist only blocked the effects of the cannabinoid agonist, and the opioid antagonist only blocked the effects of the opioid agonist. These findings contrast with those of Spano et al (2004) that rimonabant and the opioid antagonist, naloxone, were both capable of preventing WIN 55,212-2-induced as well as heroin-induced reinstatement of WIN 55,212-2 seeking in rats. This discrepancy could be due to differences between rats and monkeys, or due to differences between THC and WIN 55,212-2, which show different profiles of non-cannabinoid receptor binding.

In conclusion, THC, the main psychoactive ingredient in cannabis, has been shown to have strong reinforcing effects in a non-human primate, the squirrel monkey, under procedures that now include fixed-ratio drug-taking and second-order drug-seeking. Extended sequences of drug-seeking behavior can be maintained by THC-associated environmental cues, even when THC is not delivered until the end of the experimental session. This allows the study of THC-seeking behavior that occurs in the absence of direct effects of THC. The maintenance of high rates of THC seeking depended on both the presentation of the cues and the delivery of THC at the end of recent sessions. When both the cue presentations and THC delivery were discontinued, THC seeking occurred only at very low levels. After such a period of abstinence, THC seeking could be reinstated either by presentations of the stimulus or by passive exposure to THC, other cannabinoid receptor agonists, the endocannabinoid uptake inhibitor AM404 or morphine, but not by cocaine. This represents the first demonstration of cue- and drug-induced reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking in non-human primates. The cannabinoid antagonist, rimonabant, produced decreases in THC seeking for as long as the rimonabant treatment continued. In contrast, the opioid antagonist, naltrexone, decreased THC seeking only during the first two sessions of treatment. Rimonabant has received attention as a candidate medication for preventing the behavioral effects of drug-related and feeding-related cues in general. The ability of rimonabant to block both cue-induced THC seeking and the direct reinforcing effects of THC in a non-human primate model of cannabinoid dependence suggests that rimonabant, or other cannabinoid antagonists, may be particularly efficacious for the treatment of cannabinoid abuse, helping to both achieve and maintain abstinence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH, DHHS. We thank Eric Thorndike for programming assistance and Kathleen Stillwell and Dr. Ira Baum for their excellent surgical assistance with catheter implantation and maintenance.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES/CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that over the past 5 years, P.M. has received compensation from Alexza Pharmaceuticals. There is no conflict of interest for any of the other authors listed in this manuscript.

References

- Arroyo M, Markou A, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Acquisition, maintenance and reinstatement of intravenous cocaine self-administration under a second-order schedule of reinforcement in rats: effects of conditioned cues and continuous access to cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;140:331–344. doi: 10.1007/s002130050774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolato M, Campolongo P, Mangieri RA, Scattoni ML, Frau R, Trezza V, La RG, Russo R, Calignano A, Gessa GL, Cuomo V, Piomelli D. Anxiolytic-like properties of the anandamide transport inhibitor AM404. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2652–2659. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CEWG. Proceedings of the Community Epidemiology Work Group. II. National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH Publication No 05-5365A,; Bethesda, MD: 2004. Epidemiologic Trends in Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- CEWG. Proceedings of the Community Epidemiology Work Group. Highlights and Executive Summary. National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH Publication No 07-6200; Bethesda, MD: 2007. Epidemiologic Trends in Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen C, Kodas E, Griebel G. CB1 receptor antagonists for the treatment of nicotine addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen C, Perrault G, Voltz C, Steinberg R, Soubrie P. SR141716, a central cannabinoid (CB(1)) receptor antagonist, blocks the motivational and dopamine-releasing effects of nicotine in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2002;13:451–463. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200209000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, Glantz MD, Stinson FS. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries TJ, Homberg JR, Binnekade R, Raaso H, Schoffelmeer AN. Cannabinoid modulation of the reinforcing and motivational properties of heroin and heroin-associated cues in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:164–169. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries TJ, Schoffelmeer AN. Cannabinoid CB1 receptors control conditioned drug seeking. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries TJ, Shaham Y, Homberg JR, Crombag H, Schuurman K, Dieben J, Vanderschuren LJ, Schoffelmeer AN. A cannabinoid mechanism in relapse to cocaine seeking. Nat Med. 2001;7:1151–1154. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economidou D, Mattioli L, Cifani C, Perfumi M, Massi M, Cuomo V, Trabace L, Ciccocioppo R. Effect of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR-141716A on ethanol self-administration and ethanol-seeking behaviour in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;183:394–403. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden J, Ko T. The effects of anorexic drugs on free-fed rats responding under a second-order FI15-min (FR10:S) schedule for high incentive foods. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:61–69. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32801456c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Second-order schedules of drug reinforcement in rats and monkeys: measurement of reinforcing efficacy and drug-seeking behaviour. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;153:17–30. doi: 10.1007/s002130000566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattore L, Spano MS, Deiana S, Melis V, Cossu G, Fadda P, Fratta W. An endocannabinoid mechanism in relapse to drug seeking: a review of animal studies and clinical perspectives. Brain Res Rev. 2007a;53:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattore L, Vigano D, Fadda P, Rubino T, Fratta W, Parolaro D. Bidirectional regulation of mu-opioid and CB1-cannabinoid receptor in rats self-administering heroin or WIN 55,212-2. Eur J Neurosci. 2007b;25:2191–2200. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SR. Comparable behavior maintained under fixed-ratio and second-order schedules of food presentation, cocaine injection or d-amphetamine injection in the squirrel monkey. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1973;186:18–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SR, Kelleher RT, Morse WH. Second-order schedules of drug injection. Fed Proc. 1975;34:1771–1776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SR, Tang AH. Behavior maintained under second-order schedules of intravenous morphine injection in squirrel and rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1977;51:235–242. doi: 10.1007/BF00431630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justinova Z, Goldberg SR, Heishman SJ, Tanda G. Self-administration of cannabinoids by experimental animals and human marijuana smokers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005a;81:285–299. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justinova Z, Solinas M, Tanda G, Redhi GH, Goldberg SR. The endogenous cannabinoid anandamide and its synthetic analog R(+)-methanandamide are intravenously self-administered by squirrel monkeys. J Neurosci. 2005b;25:5645–5650. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0951-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justinova Z, Tanda G, Munzar P, Goldberg SR. The opioid antagonist naltrexone reduces the reinforcing effects of Delta 9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in squirrel monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;173:186–194. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1693-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justinova Z, Tanda G, Redhi GH, Goldberg SR. Self-administration of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) by drug naive squirrel monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;169:135–140. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1484-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Goldberg SR. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists as promising new medications for drug dependence. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:875–883. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.077974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado R, Valverde O, Berrendero F. Involvement of the endocannabinoid system in drug addiction. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura-Palacios EM, Winsauer PJ, Moerschbaecher JM. Effects of the cannabinoid ligand SR 141716A alone or in combination with delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol or scopolamine on learning in squirrel monkeys. Behav Pharmacol. 2000;11 :377–386. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro M, Carrera MR, Fratta W, Valverde O, Cossu G, Fattore L, Chowen JA, Gomez R, del AI, Villanua MA, Maldonado R, Koob GF, Rodriguez de Fonseca F. Functional interaction between opioid and cannabinoid receptors in drug self-administration. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5344–5350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05344.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien C. Drug addiction and drug abuse. In: Hardman J, Limbird L, Gilman AG, editors. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. pp. 621–642. [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Goldberg SR. Self-administration of drugs in animals and humans as a model and an investigative tool. Addiction. 2007;102:1863–1870. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CW, Panlilio LV, Goldberg SR. Second-order schedules of drug self-administration in animals. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:327–344. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinas M, Panlilio LV, Antoniou K, Pappas LA, Goldberg SR. The cannabinoid CB1 antagonist N-piperidinyl-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl) -4-methylpyrazole-3-carboxamide (SR-141716A) differentially alters the reinforcing effects of heroin under continuous reinforcement, fixed ratio, and progressive ratio schedules of drug self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:93–102. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.047928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spano MS, Fattore L, Cossu G, Deiana S, Fadda P, Fratta W. CB1 receptor agonist and heroin, but not cocaine, reinstate cannabinoid-seeking behaviour in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:343–350. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spealman RD, Barrett-Larimore RL, Rowlett JK, Platt DM, Khroyan TV. Pharmacological and environmental determinants of relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:327–336. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-32, DHHS Publication No SMA 07-4293; Rockville, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Munzar P, Goldberg SR. Self-administration behavior is maintained by the psychoactive ingredient of marijuana in squirrel monkeys. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1073–1074. doi: 10.1038/80577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton-Jones ZD, Vickers SP, Clifton PG. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A reduces appetitive and consummatory responses for food. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179:452–460. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Gilbert JG, Peng XQ, Pak AC, Li X, Gardner EL. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 inhibits cocaine-primed relapse in rats: role of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8531–8536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0726-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]