Abstract

Objective

Infobuttons are decision support tools that provide links within electronic medical record systems to relevant content in online information resources. The aim of infobuttons is to help clinicians promptly meet their information needs. The objective of this study was to determine whether infobutton links that direct to specific content topics (“topic links”) are more effective than links that point to general overview content (“nonspecific links”).

Design

Randomized controlled trial with a control and an intervention group. Clinicians in the control group had access to nonspecific links, while those in the intervention group had access to topic links.

Measurements

Infobutton session duration, number of infobutton sessions, session success rate, and the self-reported impact that the infobutton session produced on decision making.

Results

The analysis was performed on 90 subjects and 3,729 infobutton sessions. Subjects in the intervention group spent 17.4% less time seeking for information (35.5 seconds vs. 43 seconds, p = 0.008) than those in the control group. Subjects in the intervention group used infobuttons 20.5% (22 sessions vs. 17.5 sessions, p = 0.21) more often than in the control group, but the difference was not significant. The information seeking success rate was equally high in both groups (89.4% control vs. 87.2% intervention, p = 0.99). Subjects reported a high positive clinical impact (i.e., decision enhancement or knowledge update) in 62% of the sessions.

Limitations

The exclusion of users with a low frequency of infobutton use and the focus on medication-related information needs may limit the generalization of the results. The session outcomes measurement was based on clinicians' self-assessment and therefore prone to bias.

Conclusion

The results support the hypothesis that topic links are more efficient than nonspecific links regarding the time seeking for information. It is unclear whether the statistical difference demonstrated will result in a clinically significant impact. However, the overall results confirm previous evidence that infobuttons are effective at helping clinicians to answer questions at the point of care and demonstrate a modest incremental change in the efficiency of information delivery for routine users of this tool.

Introduction

Clinicians often face information needs in the course of patient care and most of these needs are left unsatisfied. 1–8 In 1985, Covell observed that physicians raised two questions for every three patients seen in an outpatient setting. 1 In 70% of the cases, these questions were not answered. More recent studies have had similar results, indicating that there has been little improvement in the three decades since Covell's seminal study was published. 5,7,8

With the advent of the World Wide Web, numerous online health information resources have become available. 9 These resources have demonstrated great potential to resolve many of the physicians' information needs, especially those related to knowledge gaps. 10,11 Yet, a number of barriers, notably lack of time, lack of seamless access to resources, resource deficiencies, and clinicians' suspicions that an answer does not exist or cannot be easily found, hinder more frequent and efficient attempts to fulfill information needs that arise at the point of care. 5,8,9

A subset of the approaches to reducing those barriers and increasing the use of information resources during the course of patient care rely on the theory that the context of a particular problem dictates workers' information needs. 12 It would follow that information needs can be predicted in the context of an interaction between a clinician and a computer. “Infobuttons” are information retrieval tools that use the context of this interaction to predict the most likely information needs and to offer a list of links to resources and content topics that may fulfill them. 13–15 Several healthcare organizations have implemented infobuttons in their electronic medical record (EMR) systems. Assessments of these implementations have shown that infobutton users were able to quickly answer their questions and that these answers positively affected patient care decisions. 16–18

Infobuttons are typically implemented using a software component called an “Infobutton Manager.” 15 Infobutton Managers have a knowledge base that represents both the types of information needs that are most likely to arise in a particular context, and the available information resources that could fulfill them. 14,16 When an infobutton is clicked, context attributes are sent to the Infobutton Manager. Examples of context attributes include the clinical data element that is associated with the infobutton (e.g., a medication, a problem list item), the task or action that a user is performing in the EMR (e.g., medication order entry, laboratory results review), and data about the infobutton user (e.g., discipline) and the patient (e.g., age, gender). The Infobutton Manager responds with a web page that contains links to information resources that may be relevant in the particular context (▶). These links send a request containing a set of context parameters that are used by the target information resource to retrieve potentially relevant content. These links may also indicate the specific question or content topic in which the user is interested (e.g., dose of drug X as opposed to just drug X). In this report, we refer to the latter links as “topic links” and to those that do not specify a topic as “nonspecific links.”

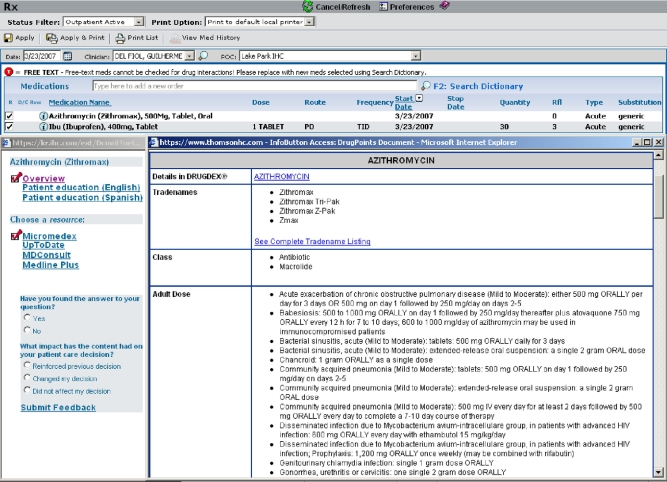

Figure 1.

A medication order entry infobutton screen showing the resulting page when an infobutton next to the medication “Azithromycin” is selected. The left panel allows users to navigate to different resources and topics (e.g., dose, adverse effects, patient education).

By using “topic links”, Infobutton Managers may further constrain the retrieved content to more closely match the clinician's implied question. As suggested by authors of previous studies, links pointing to specific topics may be more effective than nonspecific links. 18,19 However, the differences between topic links and nonspecific links have not been assessed and quantified.

The comparison between these types of links is important, especially because topic links are more difficult to implement than nonspecific links. To implement topic links, Infobutton Managers need to “wisely choose” from a potentially long list of topics those few instances that are most likely to be relevant in a given context. The knowledge that drives this decision typically relies on labor intensive studies of information needs in the context of EMR use. 6,20,21 Also, information resources need to be structured and indexed in a way to identify content relevant to the topic specified in the infobutton request. This requirement is difficult to implement and most currently available information resources do not meet it.

In this study, we assess whether topic links are more effective than nonspecific links at answering clinicians' questions at the point of care. More specifically, we test the hypothesis that topic links allow infobutton users to find answers to their questions more quickly and more reliably than nonspecific links.

Methods

Study Environment

This study was conducted at Intermountain Healthcare (“Intermountain”), an integrated delivery system of 21 hospitals and over 120 outpatient clinics located in Utah and southeastern Idaho. Clinicians at Intermountain have access to a web-based EMR system called HELP2 Clinical Desktop that offers a wide variety of modules, including laboratory results, problem list, and medication order entry. 22 These modules have had infobutton links since September 2001 (▶). From January to October, 2007, an average of approximately 900 clinicians clicked on infobuttons at least once every month. Infobuttons at Intermountain are implemented using an Infobutton Manager. This application is similar in concept and functionality to other implementations that have been previously reported. 14,15,18 The Intermountain Infobutton Manager knowledge base contains a set of rules that define the content topics and resources that are thought to be relevant in various contexts. Specific details of the Infobutton Manager implementation at Intermountain have been described elsewhere. 14,16

Study Design

In this study, we assessed the relative effectiveness of two configurations of Intermountain's medication order entry infobuttons. The medication order entry module is used in most outpatient clinics at Intermountain and hosts the most popular of the infobutton implementations. This application accounted for approximately 70% of the infobutton sessions conducted in 2007.

The study was designed as a randomized controlled trial. Subjects were allocated to a control group with access to nonspecific links or to an intervention group with access to topic links. Although clinicians had access to five different information resources when clicking on medication order entry infobuttons, only Micromedex® (Thomson Healthcare, Englewood, CO) provided access to topic links. As a result, links to the other four resources were identical in the control and intervention groups. The study occurred between May and November, 2007.

Topics

To determine the most important topics and the order in which to display them for this study, we used a focus group composed of seven users of the HELP2 medication order entry module. A list of 17 content topics available in the Micromedex® Infobutton Access™ (Montvale, NJ) API (application program interface) was presented and each member was asked to select and rank the topics that reflected the five most common information needs that arise while entering medication orders. The outcome of this focus group was used to determine the topics displayed as a part of the intervention group's user interface.

During the study, for the intervention group, a maximum of five topics were displayed in the navigation panel, along with a link to display “more topics.” Two additional rules were implemented to further constrain the list of topics offered: 1) “pediatric dose” was displayed only in the case of patients younger than 12 years old; 2) “breastfeeding” and “pregnancy category” were restricted to females in a typical reproductive age (i.e., between 12 and 45 years old). Once an infobutton was clicked, subjects were automatically led to a screen with the topic navigation panel and a content window showing the default topic, “adult dose.” Users could navigate to different topics using the navigation panel. Typically, the topic's content in Micromedex® was not longer than a few “bullet items,” which could fit in one computer screen.

Nonspecific Links

In the configuration used in the control group, a link labeled “overview” was displayed at the top of the list in the navigation panel. Once an infobutton was clicked, subjects were directed to the top of a complete drug summary document in Micromedex®, which covered a series of topics that were relevant to the drug. In the drug summary, users had to browse the content (i.e., scroll) to find the topic of interest, since the drug summary documents were generally several paragraphs long, generally spanning through several computer screens.

Subject Selection Criteria

Clinicians who had conducted a minimum of 10 medication infobutton sessions within the three-month period preceding the enrollment time were considered eligible for this study. A subset of users was still using an older version of the medication order entry module, which provided access to a prior version of infobuttons that did not have the necessary monitoring infrastructure for this study. These users were not considered eligible. A number of users transitioned from the old to the new version during the study period, becoming eligible for the study. These users were enrolled and assigned to one of the study groups in batches whenever a minimum of four eligible users became available.

Measurements

The study's dependent variables were 1) time spent seeking information (infobutton session duration); 2) the number of infobutton sessions conducted in the study period; and 3) the outcome and impact of the information seeking.

A session was timed from the moment the infobutton was clicked to the point when the user closed the navigation panel or the content page. The pretest data showed the presence of important outliers, where sessions were either too short to allow content to be loaded and some time for reading or too long to be reasonably conducted in a busy point of care environment. To minimize the noise caused by these outliers, ad hoc thresholds were determined and used to limit the sessions collected for analysis. The lower threshold (six seconds) was based on the minimum time needed to load the content and to allow glancing through a list with a few bullet items. The upper threshold (10 minutes) was set at a point where approximately 90% of the sessions in the pretest period were considered eligible.

A post-session questionnaire was adapted from an instrument suggested by Pluye et al. 23 The questionnaire contained two questions which measured 1) the outcome of the information seeking, and 2) the impact of the information found on the clinician. The first question was analyzed as a binary outcome (i.e., yes or no). Responses where users answered “not applicable” to the first question were excluded from the analysis. The second question was translated into the scale proposed by Pluye et al., where session impact was assigned a score from one (no impact, extreme frustration) to seven (decision enhancement). The questionnaire was presented to users immediately after an infobutton session ended. To minimize disruption in the participants' workflow, the questionnaire was displayed randomly in only 30% of the sessions.

All study data, including responses to the post-session questionnaire, were stored in the infobutton monitoring log, a database that captures detailed records of the interactions between users and infobuttons.

Randomization Procedure

Subjects were matched according to their median session duration (main outcome variable) and total number of sessions conducted during the 3-month pretest period. Next, members of each pair were randomly allocated to the study groups, so that each subject in the intervention group had a corresponding match the control group. The goal was to guarantee the composition of two groups with very similar pretest measurements on the two main outcome variables.

Analysis

For the session time analysis, the median duration of the sessions conducted by each subject was calculated. Next, the medians in each pair were compared to assess differences between the two groups. This procedure was followed to minimize outliers and to combine multiple session duration measurements into a single aggregated measurement for each subject. The permutation test was used to determine whether there was a statistical difference between the medians of each subject pair. Similarly, the permutation test was used to analyze the difference between the total number of sessions per subject in each pair. The chi-square test was used to compare session outcomes (i.e., successful vs. not successful). The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare session impact scores.

Descriptive statistics and qualitative data regarding the following items were also reported: 1) Description of unsuccessful sessions according to the post-session survey; 2) analysis of sessions in the intervention group where subjects clicked on a topic different than the default one; and 3) frequency of infobutton sessions by topic in the intervention group.

Statistical analyses were performed using R 2.5.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Utah (IRB_00020124) and Intermountain Healthcare (RMS 1000660).

Results

A total of 104 subjects were eligible for the study. These subjects were enrolled in four batches as new users began using the new medication order entry module: 1) First batch, 56 subjects, May 15th, 2007; 2) Second batch, eight subjects, July 2nd, 2007; 3) Third batch, six subjects, August 3rd, 2007; 4) Fourth batch, 16 subjects, August 28th, 2007; 5) Fifth batch, eighteen subjects, September 25th, 2007.

The study subjects conducted 4,101 sessions in the study period. Out of these, 3,729 (90%) met the session duration eligibility range. Of the 104 enrolled subjects, 90 (87%) used the infobuttons at least once (half from each group). Further analysis showed that 12 (86%) of the 14 users who did not use infobuttons in the study period never accessed the medication order entry module of the HELP2 EMR during the study period and hence were not exposed to the medication infobuttons. Of the study subjects who accessed the medication order entry module, 98% (102 out of 104) also accessed infobuttons.

Since the analysis of session duration and number of sessions was based on paired subjects, only those pairs where both subjects conducted at least one session during the study period were included in the analysis. There were 40 pairs (77% of the total number of pairs) where both subjects had at least one session. These pairs conducted 3,260 sessions during the study period (1,792 control vs. 1,468 intervention).

Session Duration and Number of Sessions

▶ shows the median session duration and median number of sessions conducted in each group during the pretest period and study period. In the pretest period, no significant difference was found between pairs in the two groups regarding the session duration and number of sessions.

Table 1.

Table 1 Median Session Duration and Number of Sessions Conducted per Group in the Pretest Period and Study Period

| Measurement | Control | Intervention | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest period | |||

| Median session duration (seconds) | 40.5 | 39.5 | 0.35 |

| Median number of sessions | 11.5 | 12 | 0.6 |

| Study period | |||

| Median session duration (seconds) | 43 | 35.5 | 0.008 ∗ |

| Median number of sessions | 17.5 | 22 | 0.21 |

∗ Statistically significant.

In the data collected during the study, the median session duration was 17% shorter in the intervention than in the control group (35.5 seconds vs. 43 seconds respectively, p = 0.008). Subjects in the intervention group tended to use the infobuttons 21% more often than the ones in the control group, though this difference was not statistically significant (22 sessions vs. 17.5 sessions respectively, p = 0.21) (▶).

Session Outcome and Impact

Twenty five subjects (14 from the control group and 11 from the intervention group) answered the post-session survey at least once, with a total of 115 (9.9%) individual responses out of 1,161 sessions after which the survey was displayed. Out the 115 responses, 68 (58%) were from the control group and 47 (42%) from the intervention group. Two (1.7%) responses, both from the control group, were answered “not applicable” to the first question and were excluded from the analysis.

In the control group, 59 (89%) of the responses indicated that the information being sought was found compared to 41 (84%) in the intervention group (p = 0.9). The average impact score of the infobutton session was similar in the control and the intervention groups (5.3 vs. 5.5; p = 0.99). Overall, subjects reported that the information found produced a high impact (i.e., decision enhancement or learning) in 62% of the responses associated with a successful session. Conversely, subjects reported a moderate or high level of frustration in 80% of the responses associated with unsuccessful sessions. The frequency of responses by session impact category in each study group is provided in ▶.

Table 2.

Table 2 Session Impact Frequency Distribution

| Control (n = 66) | Intervention (n = 47) | Overall (N = 113) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative impact | |||

| No impact, extremely frustrated | 3 (4.5%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| No impact, moderately frustrated | 2 (3.0%) | 3 (6.4%) | 5 (4.4%) |

| No impact, no frustration | 3 (4.5%) | 4 (8.5%) | 7 (6.2%) |

| Moderate positive impact | |||

| Reinforced or confirmed previous decision | 14 (21%) | 5 (11%) | 19 (17%) |

| Recalled something I had forgotten | 6 (9.1%) | 4 (8.5%) | 10 (8.8%) |

| High positive impact | |||

| Learned something or updated my knowledge | 12 (18%) | 9 (19%) | 21 (19%) |

| Enhanced my decision | 23 (35%) | 18 (38%) | 41 (36%) |

| Did not answer | 3 (4.5%) | 4 (8.5%) | 7 (6.2%) |

Analysis of Unsuccessful Sessions

Subjects reported an unsuccessful infobutton session in 13 (12%) of the responses. In 8 (62%) of these 13 sessions, Micromedex® did not retrieve content that matched the infobutton search criteria. Further infobutton log analysis showed that Micromedex® did not retrieve any content in 147 (4%) of the 3,729 eligible study sessions. These cases were distributed similarly across both groups: 4.1% of these sessions occurred in the control group versus 4.25% in the intervention group. The primary reasons for failure to retrieve content were: 1) inaccurate or absent mappings between medication codes used at Intermountain and NDC codes used by infobuttons to request content from Micromedex® and 2) absence of content in Micromedex®. For the remaining five unsuccessful sessions in which relevant drug summaries were retrieved from Micromedex®, the reasons for failure is not known. Users closed their sessions without trying different topics or resources offered in the navigation panel in 11 (84.6%) of the unsuccessful sessions.

Topics Selected in the Intervention Group

▶ shows how many times each topic was selected as the first content option in intervention group sessions as well as the ranking according to the focus group. The popularity of each topic was generally similar to the ranking suggested by the focus group, except that “patient education” was selected more frequently than the focus group would have predicted and “breast feeding” less frequently. ▶ also indicates that the default option, i.e., “adult dose,” was overridden (i.e., users selected a different topic) in 32.7% of the sessions.

Table 3.

Table 3 Number of Times Each Topic was Selected as the First Option in a Session for the Intervention Group

| Topic | Number of Sessions (% of total number of sessions) N = 1,498 | Ranking According to Focus Group (1 to 12) |

|---|---|---|

| Adult Dose | 1,008 (67.3%) | 1 |

| Adverse Effects | 224 (15.0%) | 3 |

| Patient Education | 64 (4.3%) | 10 |

| Pediatric Dose | 64 (4.3%) | 2 |

| Precautions | 31 (2.1%) | 9 |

| Contraindications | 29 (1.9%) | 5 |

| Drug Interaction | 26 (1.7%) | 7 |

| Pregnancy Category | 20 (1.3%) | 6 |

| How Supplied | 16 (1.1%) | 8 |

| Class | 10 (0.7%) | 11 |

| Breast Feeding | 4 (0.3%) | 4 |

| Dose Adjustments | 2 (0.1%) | 12 |

Discussion

This study compared two approaches to infobutton links (i.e., topic links and nonspecific links) regarding information seeking effort and success rate. To our knowledge, this is the first study to make this comparison.

The study presents evidence to support the study alternate hypothesis that session length was shorter in intervention group. In fact, users spent 17% less time on their information seeking efforts when provided with links that attempt to lead them to content that more specifically addressed their questions. On one hand, this difference may be deemed an important finding, given that lack of time and seamless access are among the main barriers to the use of online health information resources at the point of care 1,5 and one of the key motivations of infobuttons is to reduce these barriers. 14,17,18 On the other hand, it may be argued that the absolute session length difference between the control and intervention groups was not large enough to produce an impact that is clinically significant.

In theory, the idea behind topic links is that these links lead clinicians to content subsections that are likely to be more closely related to the clinician's question, reducing exposure to unnecessary information and minimizing cognitive effort. Cognitive psychology theories support the notion that information systems should minimize cognitive overload, providing the minimal amount of information to support decisions. This view has been well elaborated in a study by Weir et al., who stated that “any computerized information system needs to be designed to support strategies that allow for ‘fast and frugal’ decision-making. These strategies are often used by decision-makers in the real world. They include multiple methods for rapidly identifying the minimally sufficient data to support a decision, attempts to efficiently balance accuracy versus speed, and creating personal information displays that support recognition-primed actions.” 29 Therefore, topic links may have reduced clinicians' cognitive workload when compared to unspecific links. Yet, the present study has not aimed at proving such an impact. Future studies, with a stronger qualitative focus, may be necessary to address this question more appropriately.

A more pronounced difference may have been observed if, instead of fixing the default topic to “adult dose,” a more accurate prediction method were employed to determine the topic that is most likely to match the clinician's information need in a given context. In the intervention group, users frequently had to override the default topic, a task that demands additional cognitive effort and time from users. This overhead can be minimized if the default topic is accurately predicted. In a previous study, we have demonstrated that accurate prediction models can be derived from data of previous infobutton sessions using machine learning methods, suggesting this to be a sound alternative for further improvement of infobuttons. 24,25

No statistical difference was found regarding infobutton usage. According to the technology acceptance model, perceived usefulness and ease of use of a technology are the main determinants of actual use. 26 Therefore, it is possible that users may have not perceived the relative advantage of topic links regarding usefulness and ease of use when compared to nonspecific links. Another potential explanation is that the study subjects, who were all frequent users, already used infobuttons whenever a need was perceived. Finally, a significant difference might have been detected if the study were conducted for a longer period of time, giving users sufficient experience with the improved functionality to affect their perceived usefulness and ease of use. The fact that almost half of the subjects were enrolled during the course of the study and therefore had even less time to interact with topic links would have contributed to this.

There was no significant difference in terms of information seeking success rate and impact. This may be explained by the fact that the baseline success rate and impact were already very high, leaving little room for improvement, at least within the context of medication order entry. Other infobutton studies have also shown high session success rates, supporting this hypothesis. 17,18

The analysis of unsuccessful sessions raised two important points. First, users tended to quit their search effort very quickly without looking at different topics and information resources that were offered. The results were more pronounced than those of general purpose search engines, where the majority of users perform up to two queries and view up to two web sites when searching for content. 27 The difference may be explained by the busier nature of patient care settings and highlights the importance of information resources providing clinicians with content that rapidly addresses their questions. 5

Second, a high percentage of the reported unsuccessful sessions was due to issues related to the use of inappropriate drug codes in infobutton requests, reflecting incomplete content indexing. Once identified, these issues were all fixed, so that, in the future, similar requests will successfully retrieve content. Therefore, these issues underscore the importance of continuous monitoring of infobutton sessions as a good knowledge management practice. 28 Continuous monitoring allows problems with code mapping, content indexing, lack of content, and changes to the information resource APIs to be identified and fixed in the Infobutton Manager infrastructure or by the content provider. For example, reports of unsuccessful content requests could be shared with content providers so they can optimize content indexing or decide how to allocate content development resources.

A number of studies have assessed the effectiveness of information resources at the point of care. 30 However, differences in methodology, study population, clinical setting, goals of the information retrieval tool, and types of information needs make a comparison among these and the present study difficult and some times inappropriate. Therefore, comparisons should be considered with caution, considering the lack of a uniform methodology.

In our study, clinicians reported that they were able to find answers to their questions in 88.5% of the infobutton sessions and improved their decisions in 36.3% of these sessions. In a study conducted by Mabrabi et al., physicians reported that their questions were completely or partially answered in 73% of the information seeking sessions conducted via Quick Clinical, an online evidence system. 31 Yet, physicians in the Quick Clinical study used the tool for a variety of clinical questions including types of questions that were probably more complex. Conversely, the present study focused solely on medication-related queries.

A mixed method study conducted by Pluye et al. revealed that residents perceived that information accessed via a tool called InfoRetriever was relevant to their search objectives in 85.9% of the searches. 32 However, the concept of “relevancy” in the Pluye et al. study, did not have the same meaning as “success” in the present study, since the former does not necessarily indicate that a question has actually been answered.

A systematic review of studies that evaluated the impact of clinical information retrieval technology on physicians found that 20 to 82% of searches produced any type of positive impact on physicians. Yet, according to the authors of the review, the higher estimates were subject to recall bias, which tend to overestimate impact. Therefore, the most plausible estimates ranged from 20 to 39%. 30 In the present study, a positive impact was found in 63.7% of the infobutton sessions. Since the post-session survey was prompted immediately after the conclusion of infobutton sessions, recall bias was not likely to be an important factor in our results.

Not many studies evaluated applications that enable context-sensitive access to information resources within EMR systems. 33 In a study conducted by Maviglia et al., users were able to meet their medication-related information needs in 84% and enhanced their decisions in 15% of the sessions. 18 However, users in the present study were likely to be more experienced with infobuttons than those in the former study. While the former study included all users of a medication order entry system, our study selected a subpopulation of frequent infobutton users. In addition, the present study was performed five years after the initial release of infobuttons, while the former study was initiated once infobuttons were firstly released at their institution.

The present study found an overall median session duration of 39.3 seconds and 35.5 seconds in the intervention group. Users in the study conducted by Maviglia et al. spent 25 seconds looking for information. 18 However, the session time measurement method was different in these two studies. Session duration in the present study was measured from the infobutton click event to the content window close event, therefore the entire session was captured. Maviglia et al., on the other hand, stopped the timer when the last page viewed in a session was opened. The authors of that study estimated that users may have spent approximately 21 seconds on this last page. Therefore, their total session time can be estimated to be roughly 45 seconds, which is very similar to the median session length in our control group. Interestingly, the infobuttons in the Maviglia et al., study did not provide a topic links functionality, otherwise it is conceivable that they would have observed session lengths similar to the ones observed in the intervention group of the present study.

Cimino conducted a survey to assess the overall user satisfaction and effectiveness of infobuttons at Columbia University. Among the respondents, 74% indicated that infobuttons produced a positive effect on patient care decisions and 20% reported positive impact on patient care. 17 Differences in methodology preclude a more direct comparison between the present and Cimino's results. However, both studies provide evidence that supports the usefulness of infobuttons.

In a randomized trial, Rosembloom et al. compared two user interfaces that enabled context-sensitive access to educational material in a computerized provider order entry system (CPOE). 33 Control subjects could access educational content from a menu in the standard CPOE interface. Intervention subjects had access to an improved version, where links to educational material were visibly highlighted in the interface analogously to an automobile dashboard. The usage rate of the improved version was approximately 9 times higher than of the control group, illustrating the importance of user interface in the on-demand delivery of decision support. In our study, the improved version of infobuttons (i.e., topic links) was not associated with an increased usage. Notably, our improved version focused on promoting quicker access to relevant information as opposed to drawing attention to the availability of infobutton links. On the other hand, the results reported by Rosembloom et al. suggest that improved visibility may hold the answer to increasing the usage of infobuttons.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, since the study subjects were selected from a pool of frequent and probably enthusiastic infobutton users, the measurement of session success rate and outcome may have been overestimated for the larger group of all infobutton users. 34 Therefore, the high session success rate and outcome observed in this study cannot be generalized to low frequency infobutton users. Nevertheless, the authors believe that the current study results should generalize to high-frequency, medication-related infobutton users in other institutions. This belief is based in part on the observation that the current study results are comparable with the success rates reported in a similar study that included an entire EMR user population. 18 In addition, due to the randomization procedure, it is unlikely that the subject selection strategy has biased the comparison between the control and intervention group regarding session success rate and outcome.

Second, as previously discussed in the present report, the session length difference between the control and intervention group, though statistically significant, was not necessarily impressive in absolute terms. Our study was not able to determine whether this statistical difference was also associated with a clinically significant impact.

Third, only one information resource that provided access to topic specific medication content was available at our institution. Therefore, it is possible that variations in the information resource implementations, such as user interface, content depth, and content coverage would lead to different results. Further studies are necessary to investigate whether specific characteristics of an information resource influence the effectiveness of infobuttons.

Fourth, this study was limited to the context of medication order entry and consequently to questions related to medications. Medication questions, such as those related to dosing, drug interactions, and pregnancy category, may be more easily answered straightforwardly and objectively. On the other hand, questions related to the diagnosis, etiology, or prognosis of diseases may entail more extensive and subjective answers. Therefore, the session length, success rate, and outcome reported in the present study cannot be generalized to other EMR contexts, such as problem list review or laboratory results review.

Fifth, infobutton session success rate and outcome were measured based on clinicians' self assessment, i.e., their own perceptions and judgments which may not always be correct. Westbrook et al., for example, found out that many clinicians placed confidence in information that actually led them to incorrect answers. 35 Therefore, it is not possible to determine whether a self reported “decision enhancement” was in truth associated with a better clinical decision. Further investigation is required to objectively assess this possibility. A mixed-method approach, including techniques such as critical incidents and journey mapping, combined with log data analysis, is a promising strategy to overcome this limitation. 32,36

Last, a potentially negative side of the proposed approach is that topic links may hide pieces of information that, though not actively sought by the clinician, might still be useful, reducing the opportunities for serendipitous learning. Yet, the overall short session length associated with a high success rate in both control and intervention groups suggests that infobuttons are being used to answer very specific questions in situations where there is very little time for looking at content that does not directly answer these questions.

Future Studies

As previously noted, this study focused on one single information resource and medication order entry infobuttons. Future studies are necessary to assess whether the similar results can be observed with different information resources and different EMR contexts. Another potential area of future research is the development and evaluation of methods that are able to more accurately predict the information needs that arise in a given context as well as the resources that are most likely to fulfill these needs.

Conclusion

This study suggests that topic links allow users to find answers to their medication-related questions more quickly than nonspecific links, yet with a similar success rate. These findings are especially relevant in terms of guiding infobutton and content provider development efforts. The results also support previous studies that indicated that infobuttons are able to quickly answer clinicians' medication questions with a high success rate. 17,18 Further research is necessary to assess the effectiveness of infobuttons and, more specifically, topic links in other EMR contexts, such as problem lists and laboratory results.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gregg Snow for his support on the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

This project was supported in part by National Library of Medicine Training Grant 1T15LM007124-10 and National Library of Medicine Grant R01-LM07593.

References

- 1.Covell DG, Uman GC, Manning PR. Information needs in office practice: are they being met? Ann Intern Med 1985;103(4):596-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorman PN. Information needs in primary care: A survey of rural and nonrural primary care physicians Medinfo 2001;10:338-342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos K, Linscheid R, Schafer S. Real-time information-seeking behavior of residency physicians Fam Med 2003;35:257-260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng GY. A study of clinical questions posed by hospital clinicians J Med Libr Assoc 2004;92:445-458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Chambliss ML, Ebell MH, Rosenbaum ME. Answering physicians' clinical questions: obstacles and potential solutions J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005;12(2):217-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Currie LM, Graham M, Allen M, Bakken S, Patel V, Cimino JJ. Clinical information needs in context: an observational study of clinicians while using a clinical information system Proc AMIA Annu Symp 2003:190-194. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Graber MA, Randles BD, Monahan J, et al. What questions about patient care do physicians have during and after patient contact in the ED?. The taxonomy of gaps in physician knowledge. Emerg Med J 2007;24(10):703-706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norlin C, Sharp AL, Firth SD. Unanswered questions prompted during pediatric primary care visits Ambul Pediatr 2007;7(5):396-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hersh WR, Hickam DH. How well do physicians use electronic information retrieval systems?. A framework for investigation and systematic review. JAMA 1998;280(15):1347-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magrabi F, Coiera EW, Westbrook JI, Gosling AS, Vickland V. General practitioners' use of online evidence during consultations Int J Med Inform 2005;74(1):1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westbrook JI, Coiera EW, Gosling AS. Do online information retrieval systems help experienced clinicians answer clinical questions? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005;12(3):315-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer G, Ostwald J. Knowledge management: problems, promises, realities, and challenges IEEE Intelligent Systems 2001:60-72.

- 13.Cimino JJ, Elhanan G, Zeng Q. Supporting Infobuttons with terminological knowledge Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp 1997:528-532. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Cimino JJ, Del Fiol G. Infobuttons and Point of Care Access to KnowledgeIn: Greenes RA, editor. Clinical decision support: the road ahead. Academic Press; 2006.

- 15.Cimino JJ, Li J, Bakken S, Patel VL. Theoretical, empirical and practical approaches to resolving the unmet information needs of clinical information system users Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp 2002:170-174. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Del Fiol G, Rocha R, Clayton PD. Infobuttons at Intermountain Healthcare: Utilization and Infrastructure Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp 2006:180-184. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Cimino JJ. Use, usability, usefulness, and impact of an infobutton manager Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp 2006:151-155. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Maviglia SM, Yoon CS, Bates DW, Kuperman G. Knowledge-Link: Impact of context-sensitive information retrieval on clinicians' information needs J Am Med Inf Assoc 2006;13:67-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reichert JC, Glasgow M, Narus SP, Clayton PD. Using LOINC to link an EMR to the pertinent paragraph in a structured reference knowledge base Proc AMIA Symp 2002:652-656. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Cimino JJ, Li J, Graham M, et al. Use of online resources while using a clinical information system AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2003:175-179. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Allen M, Currie LM, Graham M, Bakken S, Patel VL, Cimino JJ. The classification of clinicians' information needs while using a clinical information system AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2003:26-30. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Clayton PD, Narus SP, Huff SM, et al. Building a comprehensive clinical information system from components. The approach at Intermountain Health Care. Methods Inf Med 2003;42:1-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pluye P, Grad RM. How information retrieval technology may impact on physician practice: An organizational case study in family medicine J Eval Clin Pract 2004;10:413-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Del Fiol G, Haug PJ. Use of Classification Models Based on Usage Data for the Selection of Infobutton Resources AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2007:171-175. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Del Fiol G, Haug PJ. Infobuttons and classification models: a method for the automatic selection of online information resources to fulfill clinicians' information needs J Biomed Inform 2008;41:655-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis FD, Bagozzi RP, Warshaw PR. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models Manag Sci 1989;35(8):982-1003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jansen BJ, Spink A, Saracevic T. Real life, real users, and real needs: a study and analysis of user queries on the web Info Proc Manag 2000;36:207-227. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Cimino JJ. Auditing Dynamic Links to Online Information Resources AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2007:448-452. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Weir CR, Nebeker JJ, Hicken BL, Campo R, Drews F, Lebar B. A cognitive task analysis of information management strategies in a computerized provider order entry environment J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007;14(1):65-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pluye P, Grad RM, Dunikowski L, Stephenson R. Impact of clinical information-retrieval technology on physicians: a literature review of quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies Int J Med Inform 2005;74:745-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magrabi F, Coiera EW, Westbrook JI, Gosling AS, Vickland V. General practitioners' use of online evidence during consultations Int J Med Inform 2005;74(1):1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pluye P, Grad RM, Mysore N, et al. Systematically assessing the situational relevance of electronic knowledge resources: a mixed methods study J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007;14(5):616-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenbloom ST, Geissbuhler AJ, Dupont WD, et al. Effect of CPOE user interface design on user-initiated access to educational and patient information during clinical care J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005;12(4):458-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magrabi F, Westbrook JI, Coiera EW. What factors are associated with the integration of evidence retrieval technology into routine general practice settings? Int J Med Inform 2007;76(10):701-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Westbrook JI, Gosling AS, Coiera EW. The impact of an online evidence system on confidence in decision making in a controlled setting Med Decis Making 2005;25(2):178-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westbrook JI, Coiera EW, Gosling AS, Braithwaite J. Critical incidents and journey mapping as techniques to evaluate the impact of online evidence retrieval systems on health care delivery and patient outcomes Int J Med Inform 2007;76(2–3):234-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]