Abstract

Objective

Endotoxin (LPS) enhances microvascular thrombosis in mouse cremaster venules. Since von Willebrand factor (VWF) and P-selectin are suggested to mediate LPS-induced platelet-microvessel interactions, we determined whether VWF and P-selectin contribute to microvascular thrombosis in endotoxemia.

Methods and results

A light/dye-induced thrombosis model was used in cremaster microvessels of saline or LPS-injected mice (wild type, P-selectin-deficient, VWF-deficient, or littermate controls). In each strain except VWF-deficient mice, LPS enhanced thrombosis in venules, resulting in ∼30-55% reduction in times to thrombotic occlusion. LPS had no effect on thrombosis in VWF-deficient mice, although these mice had similar systemic responses to LPS (tachycardia, thrombocytopenia, and plasma coagulation markers). VWF-deficient mice demonstrated prolonged times to thrombotic occlusion relative to littermates. LPS increased plasma VWF in each strain studied. While immunofluorescence in wild type mice failed to detect LPS-induced differences in microvascular VWF expression, it revealed markedly higher VWF expression in venules relative to arterioles.

Conclusions

VWF mediates light/dye-induced microvascular thrombosis and endotoxin-induced enhancement of thrombosis in mouse cremaster venules; P-selectin is not required for enhanced thrombosis in response to endotoxin. Enhanced VWF expression in venules relative to arterioles has potential implications for the differences in thrombotic responses among these microvessels.

Keywords: Endotoxin, platelets, venules, intravital microscopy, sepsis

Sepsis, a systemic response to infection, is a major contributor to mortality in intensive care units1, associated with endothelial dysfunction and a prothrombotic state2. Endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) is a cell wall component of gram-negative bacteria, which reproduces many manifestations of gram-negative sepsis3,4 and is used frequently in experimental sepsis models. Endotoxemia promotes platelet adhesion to microvessels in vivo5-7, microvascular thrombosis8-10, and enhances light/dye-induced microvascular thrombosis6,11. While the mechanisms responsible for prothrombotic manifestations of endotoxemia remain to be fully understood, suggested mediators include P-selectin and von Willebrand factor (VWF). P-selectin is expressed on the surface of activated endothelial cells and platelets12 and may contribute to a prothrombotic state by several mechanisms. These include: a) mediating leukocyte-dependent platelet adhesion to microvessels via its ligand P-selectin glycoprotein-1 (PSGL-1)13, b) mediating adhesion of ultralarge VWF multimers to endothelium14, c) recruiting microparticles bearing tissue factor and PSGL-1 to developing thrombi15, d) promoting shear-dependent platelet aggregation16, and e) promoting a systemic prothrombotic state via its soluble form17. P-selectin expression is increased in various tissues in endotoxemia18 and has been implicated as a mediator of platelet-microvessel interactions in this and various other inflammatory conditions7,19.

Another potential mediator of these responses is VWF, a multimeric protein produced by endothelial cells and megakaryocytes20. VWF is stored in Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells and alpha granules of platelets. In the circulation, or when released from storage granules, VWF may bind to various receptors or counter-ligands relevant to hemostasis and thrombosis, including Factor VIII, glycoprotein Ibα, integrin αIIbβ3, collagen21, and P-selectin22. Endothelial VWF release, especially in the hyperactive ultra-large (UL) forms, is enhanced by various inflammatory stimuli, including endotoxin23-25. Further, administration of endotoxin enhances plasma VWF levels in mice26 and humans27. A reactive multimeric form of this molecule, ULVWF, mediates microvascular thrombosis in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura28. ULVWF multimers have also been described in clinical cases of severe sepsis29,30, suggesting a potential role for VWF in microvascular thrombosis in this entity. Given these findings, we tested the hypotheses that VWF and P-selectin mediate the enhanced microvascular thrombosis induced by endotoxin.

Materials and Methods

Male mice, ∼30 g of weight, were studied; all protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Baylor College of Medicine. We studied C57BL/6J (wild type), P-selectin-deficient31, VWF-deficient32 mice, and their littermate controls. P-selectin-deficient mice have been backcrossed onto a C57BL6/J background for at least 10 generations33, prior to homozygous breeding. VWF-deficient mice and their littermate controls (backcrossed on a C57BL/6J background for >8 generations) were generated by heterozygous breeding. Strains originated from the Jackson Laboratories; P-selectin- and VWF-deficient mice were genotyped by PCR analysis of tail clippings.

Animal preparation

Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of pentobarbital (50 mg/kg), with additional doses (12.5 mg/kg) as needed. The mice were then placed on a custom Plexiglas tray and maintained at 37 °C with a homeothermic blanket, monitored with a rectal temperature probe (F.H.C., MA). A tracheotomy was performed to facilitate breathing, an internal jugular vein was cannulated for intravenous drug administration, and a carotid artery was cannulated for blood pressure and heart rate measurement. The cremaster muscle was exteriorized and prepared for intravital microscopy as described previously6,34.

Intravital microscopy and microvascular thrombosis model

The preparation was placed under an upright microscope (BX-50, Olympus, NY) and observed with a 40X water immersion objective (N.A. 0.8) and allowed to equilibrate for 30 minutes. After the equilibration period, FITC-dextran (150 kD, 10 ml/kg of a 5% solution) was injected via the venular catheter and allowed to circulate for ∼10 minutes. Thereafter, venular diameter was measured (image 1.6, NIH, public domain software) as well as mean blood cell velocity (Vdoppler, using an optical Doppler velocimeter, Cardiovascular Research Institute, Texas A&M University). Venular wall shear rate (γ) was calculated as 8(Vdoppler/1.34)/diameter35.

Following those measurements, light/dye-induced injury was begun by exposing ∼100 μm of a venule length to epi-illumination, with a 175W xenon lamp (Lambda LS, Sutter, CA) and a fluorescein filter cube (HQ-FITC, Chroma, VT). Excitation light was monitored daily (IL 1700 Radiometer, SED-033 detector, International Light, MA) and maintained at 0.6 W/cm2 as described6. Epi-illumination was applied continuously and the following times were recorded: 1) Time of onset of platelet aggregates and 2) Time of flow cessation, for at least 60 seconds. In some cases, following venular flow cessation, an arteriole was selected and the measurements repeated as outlined above.

Platelet counts

In several experiments as indicated in the text, ∼400 μl of blood were collected via the arterial catheter and placed in an EDTA-coated blood collection tube (Baxter, IL). Blood was diluted with a Unopette™ collection system (Becton Dickinson, NJ) per the manufacturer's instructions and platelets were counted with a hemocytometer.

VWF and P-selectin expression

Expression of VWF protein in cremaster venules and arterioles (identified by smooth muscle α-actin staining) was assessed by immunofluorescence. Mouse cremasters were excised and fixed in cold acetone (-20°C) for 20 minutes, washed in PBS, permeabilized in PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X 100, and blocked in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin for 15 minutes. The tissue was then co-incubated with FITC-labeled antibody against smooth muscle α-actin (Sigma, MO) and unlabeled rabbit polyclonal antibody against VWF (Dako, CA). Subsequent incubation in Texas Red-labeled goat-anti-rabbit IgG was used for secondary detection of bound anti-VWF antibody. Non-immune IgG species-matched equivalents were used in place of primary antibody for determination of non-specific background fluorescence. Labeled cremasters were mounted in Airvol (Air Products and Chemicals, PA) and digital images were captured on a DeltaVision microscope (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA) using a 40X oil immersion lens. Fluorescence intensity values for VWF labeling were evaluated using SoftWorx software (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA). For each vessel we obtained 5 measures of vascular fluorescence intensity, placing a 10 × 10 μm window on the center of the vessel, and 5 measures of interstitial fluorescence (placing the window 10 μm away from the vessel wall). Final measures were obtained by subtracting background and interstitial from vascular fluorescence values.

Measurement of plasma VWF and coagulation markers

Plasma VWF was measured with a commercially available ELISA kit (Ramco Laboratory, TX), according to the manufacturer's instructions. This kit was developed for human VWF, but the goat anti-human antibody used in the kit cross-reacts with mouse VWF. Plasma VWF was measured in saline- and LPS-injected mice of each strain except VWF-deficient mice. For these experiments, mice did not receive FITC-dextran and did not undergo light/dye-induced thrombosis.

Plasma coagulation markers were measured in saline- and LPS-injected mice of each strain. Prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) were measured using a STAGO STA-R analyzer (Diagnostica Stago, NJ). Plasma fibrinogen levels were determined using STA Fibrinogen Kit (Diagnostica Stago, NJ), thrombin-antithrombin (TAT) complexes were obtained using a commercially available ELISA kit (Enzygnost, Siemens, IL), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The TAT kit uses anti-human antibodies; however, there is cross-reactivity with murine specimens. As in the case of plasma VWF measurements, these mice did not receive FITC-dextran and did not undergo light/dye-induced thrombosis protocols.

Experimental groups

To determine the influence of endotoxemia on microvascular thrombosis, mice were injected intraperitoneally with either endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) from Escherichia coli serotype 0111:B4 (Sigma #L3024, endotoxin content 1 × 106 EU/mg) at 4 or 5 mg/kg in 0.5 ml of sterile, pyrogen-free isotonic saline, 4 hours prior to photoactivation.

For all experiments, the investigator performing intravital microscopy was blinded with regards to the injected agent (saline vs. LPS). In all cases except experiments done in P-selectin deficient mice, the investigator was also blinded to the mouse genotype, since the microvascular phenotype of P-selectin-deficient mice precluded blinding (i.e., virtual absence of rolling leukocytes in venules).

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean +/- SE except for data not distributed normally, which are shown as median ± interquartile range. Comparisons by genotype within each test group (i.e.- LPS vs. saline) were done with one-way analysis of variance with Fisher's post-hoc test, and non-parametric Mann Whitney U test, as appropriate, using Statview 5.01 statistical software (SAS Institute, NC). A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Intravital microscopy was performed on 72 mice with weight of 29.6 ± 0.5 g, venule diameter of 44.4 ± 0.3 μm and wall shear rate of 465 ± 13 s-1. There were no statistical differences in weight, microvessel diameters and wall shear rates within each comparison group (data not shown).

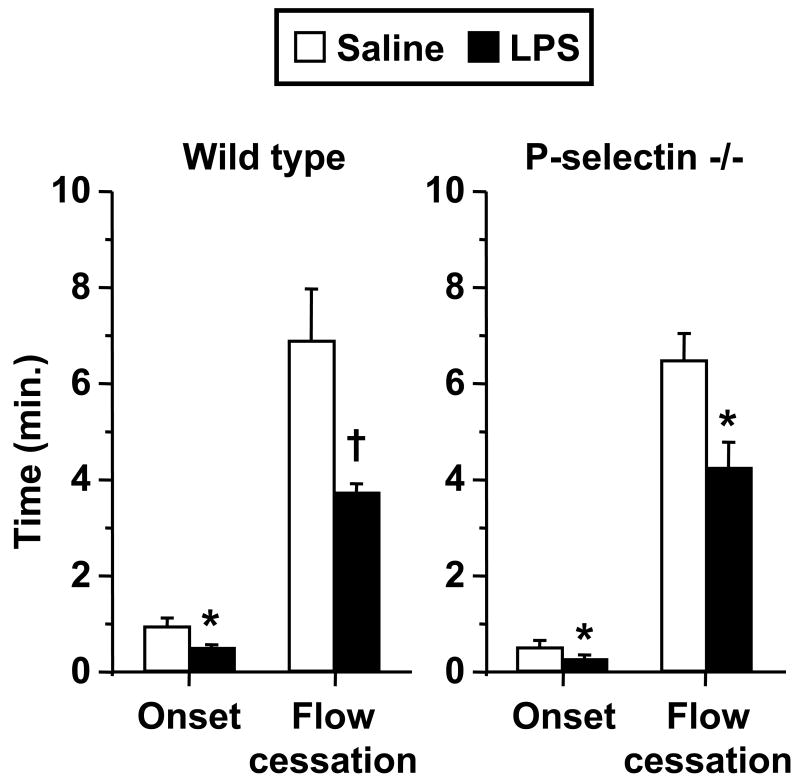

Endotoxemia enhanced microvascular thrombosis independent of P-selectin

Figure 1 depicts the influence of endotoxin on kinetics of light/dye-induced thrombosis in venules of both wild type (WT) and P-selectin-deficient mice. In WT mice, LPS enhanced both the time of onset and time to flow cessation as shown previously6. In P-selectin-deficient mice, preliminary experiments revealed lower success using the same LPS dose as in WT mice, due to frequent cremaster preparations with sluggish microvascular flow, hypotension, and/or mortality. However, a 20% lower dose of LPS was not associated with the above-mentioned problems in P-selectin-deficient mice, and resulted in enhanced microvascular thrombosis, both in time of onset and flow cessation, as shown in Figure 1. Mean arterial pressure did not differ statistically between the saline- and LPS-treated mice shown in Figure 1, although heart rate was ∼30-40% higher in LPS-treated mice in both genotypes (p < 0.01 in each case).

Figure 1.

Thrombotic responses in saline- and LPS-treated wild type (n = 10 per group) and P-selectin-deficient mice (n = 6 per group). Data shown as mean ± SE. *: p < 0.05, †: p< 0.005, for comparison with saline group.

To determine whether LPS-induced enhancement of thrombosis occurred in arterioles in a manner analogous to venules, thrombotic responses of arterioles in saline- and LPS-treated wild type mice (with similar wall shear rate of 1411 ± 105 s-1 and 1438 ± 127 s-1, respectively) were compared. Endotoxin resulted in a 24% reduction in time to flow cessation (from 32 ± 2.5 min to 24.5 ± 2.8 min, p < 0.05) with no difference in time of onset of thrombosis. Given the predominance of LPS-induced responses in venules as compared to arterioles, also noted previously6,11, subsequent assessments of the influence of LPS on thrombosis was limited to venules.

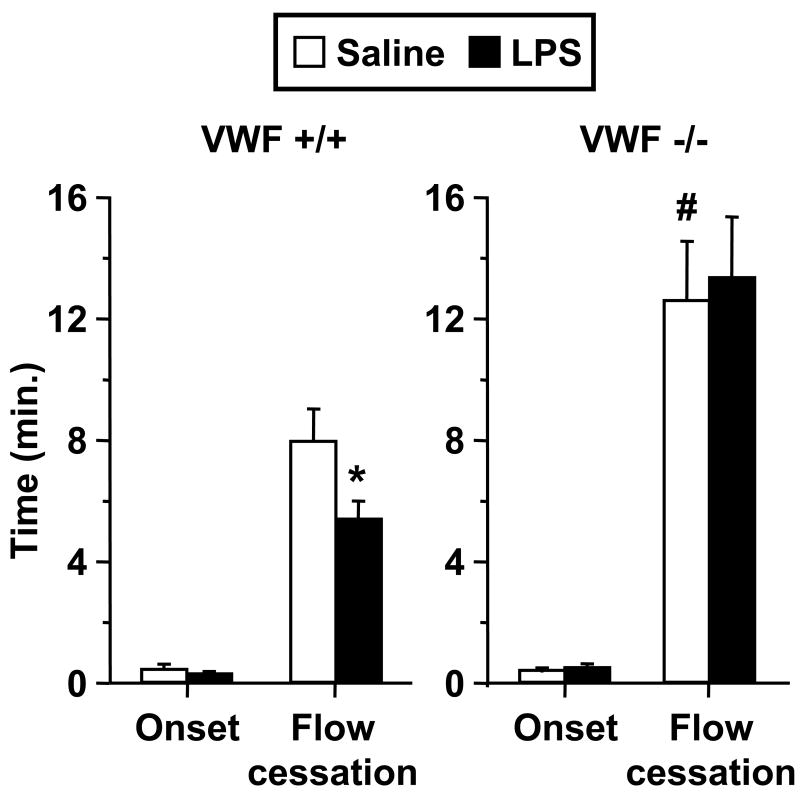

Role of VWF in microvascular thrombosis in endotoxemia

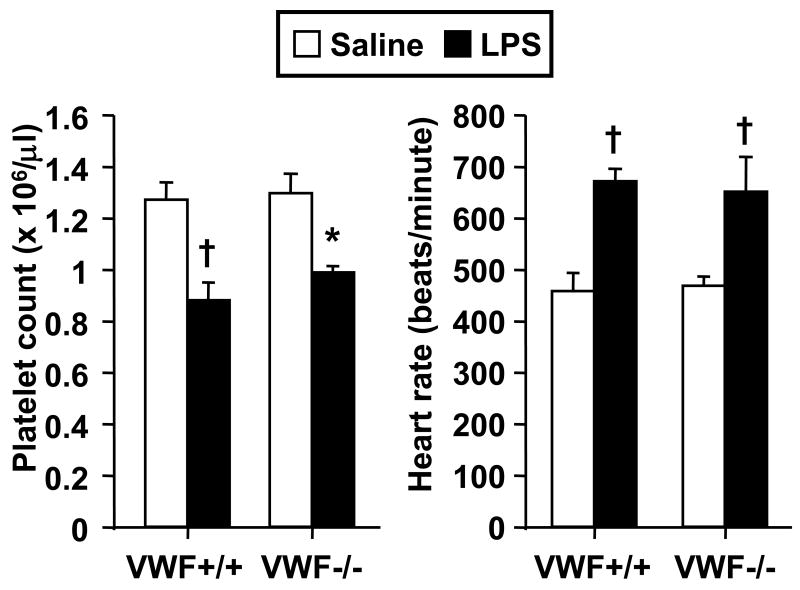

Figure 2 illustrates thrombotic responses in venules of VWF-deficient (VWF-/-) mice and littermate controls (VWF+/+). Saline-injected VWF-/- mice demonstrated significant delay in times to thrombotic occlusion as compared to littermates. Further, endotoxin had no effect on microvascular thrombosis in VWF-/- mice, while it enhanced thrombosis in VWF+/+ mice. Despite a lack of a prothrombotic response in LPS-injected VWF-/- mice, these mice had comparable systemic responses to LPS as their littermate controls with regards to reductions in circulating platelet counts and enhanced heart rate (Figure 3). Mean arterial pressure did not differ between saline- and LPS-injected mice (data not shown), consistent with prior data in this model of endotoxemia6. To exclude the possibility that the reduction in platelet counts was influenced by the light/dye-induced thrombosis model, we measured platelet counts twice in a separate group of 8 mice, first during the equilibration phase and again at the conclusion of the experiments. Platelet counts were unaffected by the thrombosis protocol, platelet counts expressed as a pre-to-post thrombosis ratio were 1.02 ± 0.05 (N.S.). Further, we measured platelet counts in a separate group of 12 saline- and LPS-injected wild type mice, which did not receive FITC-dextran or light/dye-induced thrombosis; LPS resulted in a 20% reduction in platelets at 4 hours in these mice (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Thrombotic responses in saline- and LPS-treated VWF-deficient mice (VWF-/-, n = 6 per group) and their littermate controls (VWF+/+, n = 8 per group). Data shown as mean ± SE. *: p < 0.05 for comparison with saline group, #: p < 0.05 for comparison with saline-treated VWF+/+ mice. Note different ordinate scale as compared to Figure 1.

Figure 3.

Influence of LPS on heart rate and platelet counts in VWF-deficient mice (VWF-/-, n = 6 per group) and their littermate controls (VWF+/+, n = 8 per group). Data shown as mean ± SE. *: p < 0.05, †: p< 0.005, for comparison with saline group.

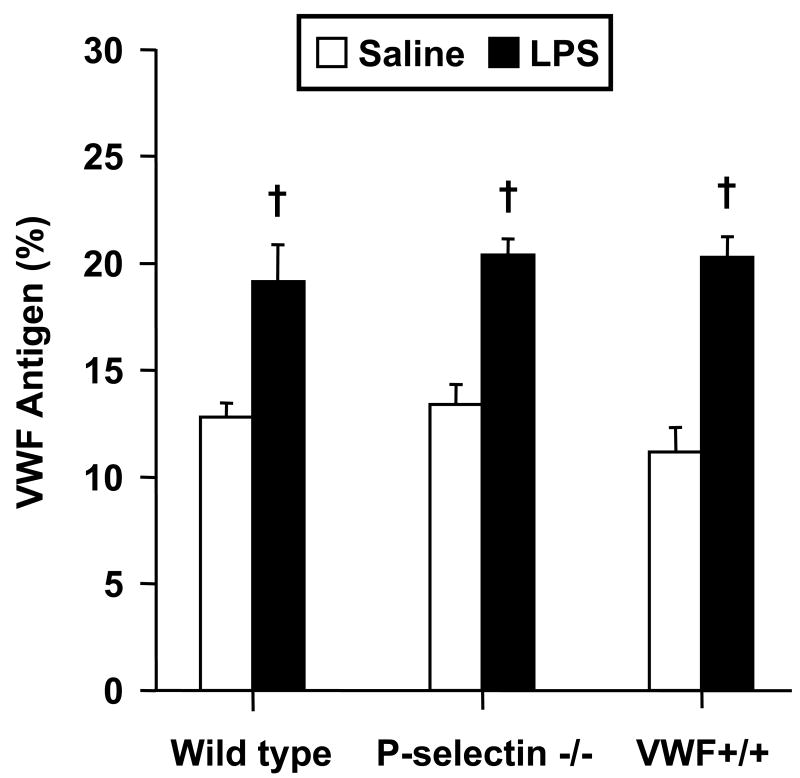

Influence of endotoxin on plasma VWF and coagulation markers

Based on the lack of endotoxin-enhanced thrombosis in VWF-deficient mice, we determined whether the present model of endotoxemia results in increased plasma VWF, as described by others26. As shown in Figure 4, LPS resulted in significant increases in plasma VWF in each genotype (not done in VWF-/- mice) 4 hours following injection, the time at which mice were studied for microvascular thrombosis. To determine whether systemic coagulation responses to LPS differed among the various groups, we measured plasma PT, aPTT, fibrinogen, and thrombin-antithrombin complexes (TAT) in saline- and LPS-treated mice of each genotype. As shown in Table 1, LPS resulted in prolonged aPTT and markedly enhanced TAT levels in each genotype. Although mean PT was slightly prolonged in LPS-treated mice of each genotype, the difference was only statistically significant in WT mice. LPS had no significant effect on plasma fibrinogen in any of the groups.

Figure 4.

Influence of LPS on plasma VWF in wild type, P-selectin-/- and VWF+/+ mice (n = 6-7 per group). Data shown as mean ± SE. †: p< 0.005 for comparison with saline group.

Table 1.

Changes in coagulation markers in Wild type, P-selectin -/-, VWF +/+ and VWF -/- mice exposed to LPS or saline.

| PT, sec | aPTT, sec | Fibrinogen, mg/dl | TAT, μg/L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | ||||

| Saline | 13.3 ± 0.3 | 26.6 ± 0.8 | 163.9 ± 5.2 | 5.5 ± 2.0 |

| LPS | 14.9 ± 0.4 * | 35.9 ± 2.0* | 167.7 ± 4.6 | 20.5 ± 2.3 † |

| P-Selectin -/- | ||||

| Saline | 12.2 ± 0.2 | 24.7 ± 0.6 | 171.7 ± 4.8 | 9.4 ± 2.7 |

| LPS | 12.8 ± 0.3 | 28.6 ± 1.2 * | 207.2 ± 16.2 | 30.3 ± 1.7 † |

| VWF +/+ | ||||

| Saline | 12.3 ± 0.3 | 24.9 ± 1.1 | 191.5 ± 5.9 | 9.0 ± 2.7 |

| LPS | 13.5 ± 0.3 | 32.1 ± 2.6 * | 218.8 ± 11.5 | 31.1 ± 10.5 * |

| VWF -/- | ||||

| Saline | 12.7 ± 0.2 | 30.9 ± 1.1 | 174.3 ± 14.3 | 5.1 ± 1.5 |

| LPS | 13.5 ± 0.4 | 39.3 ± 3.5 * | 201.4 ± 12.0 | 29.9 ± 10.3 * |

Data shown as mean ± SE of plasma prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), fibrinogen, and thrombin-antithrombin complexes (TAT).

p < 0.05,

p< 0.005, for comparison with saline group.

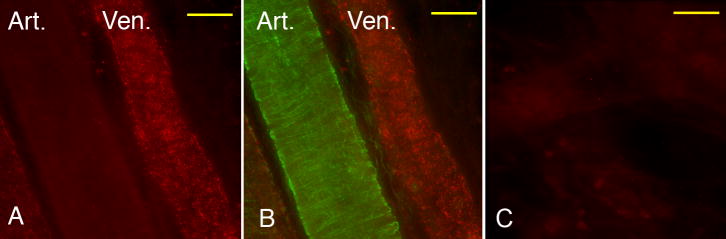

VWF expression in cremaster venules and arterioles

Using immunofluorescence, we assessed microvascular expression of VWF in saline- and LPS-injected wild type mice, obtaining 75 measures from 5 individual cremaster venules from each of 3 mice. The distribution of fluorescence intensity values (in arbitrary units, expressed as median and [interquartile range]) was extremely broad in both saline- (834 [479-1164]) and LPS-injected mice (874 [486-1362]), and thus this method precluded determining whether LPS enhanced VWF expression in cremaster microvessels. However, immunofluorescence data demonstrated that in all cremaster tissues examined, venules consistently had much higher VWF expression than arterioles (Figure 5). In view of the marked differences identified in VWF expression between venules and arterioles, we performed an additional set of experiments to determine whether thrombotic responses in arterioles differed in VWF-/- mice under control conditions (saline injected mice, n = 6 in each group). VWF-deficient mice had comparable times to onset of thrombosis as their littermate counterparts (3.6 ± 1.2 vs. 5.7 ± 0.6 min, N.S). However, VWF-deficient mice had ∼2-fold delay in time to thrombotic occlusion in arterioles as compared to littermate controls (52.0 ± 5.7 vs. 26.4 ± 2.0 min., P < 0.005)

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence staining for VWF in a cremaster venule and arteriole obtained from an LPS-treated mouse. A) Red fluorescence (VWF) demonstrates markedly greater expression in venule. B) Superimposed Green (smooth muscle alpha-actin) and Red fluorescence of the same image shown in panel A confirms smooth muscle content of arteriole. C) IgG control, red fluorescence. Bar = 30 μm.

Discussion

The primary finding of this study is a key role for von Willebrand factor in microvascular thrombosis in endotoxemia, determined in a mouse cremaster light/dye-induced thrombosis model. While LPS enhanced thrombosis in WT and P-selectin-deficient mice, it had no effect on microvascular thrombosis in VWF-/- mice. However, VWF-/- mice had comparable systemic responses to LPS as VWF+/+ mice, with regards to platelet counts and heart rate, consistent with a recent report36. Similarly, VWF-/- mice had comparable LPS-induced changes in systemic coagulation markers as the other mouse genotypes. Thus, the role of VWF in microvascular thrombosis appears distinct from the systemic coagulation changes evident in endotoxemia. The enhanced plasma levels of VWF in WT mice at the time of thrombosis induction are also consistent with a role for VWF in enhanced thrombosis in this model. A role for VWF in enhanced thrombosis in endotoxemia is supported by the observation that LPS administration to healthy humans results in enhanced plasma VWF and ULVWF27. Similarly, enhanced levels of ULVWF have been described in both adult29 and pediatric30 patients with sepsis and ischemic organ failure. Whether ULVWF newly secreted from endothelium, as opposed to plasma VWF, mediates the enhanced thrombosis to LPS could not be distinguished in the present study.

In addition to a lack of response to endotoxin, VWF-/- mice had delayed microvascular thrombosis under control conditions, consistent with data obtained in a ferric chloride model of thrombosis with this strain32, and those obtained with mice deficient in the VWF receptor GPIbα37. The findings of this study support the hypothesis that VWF mediates light/dye-induced microvascular thrombosis, as suggested previously in a rat mesentery model38. In our experiments, VWF-/- mice demonstrated delayed times to thrombotic occlusion, but comparable times of onset of thrombosis. These findings are consistent with data obtained in a laser injury model, in which VWF was not required for platelet activation, but participated in platelet accumulation in a tissue factor-mediated pathway39. Further, the greater VWF expression of mouse cremaster venules relative to arterioles (Figure 5) is consistent with the known predisposition of mouse cremaster venules to light/dye-induced thrombosis described previously19,34,40. Of interest, despite the low VWF expression in arterioles of WT mice, VWF-/- mice demonstrated prolonged times to thrombotic occlusion in arterioles as compared to littermates. While these findings are consistent with a role for plasma (and/or platelet) VWF in this model of microvascular thrombosis, we cannot exclude a contribution of arteriolar endothelial cell VWF in these responses. Differential VWF expression in mouse venules and arterioles has been identified in other vascular beds26. It is interesting to speculate that the predominance of VWF expression in cremaster venules may be related to the enhanced venular thrombotic response to LPS described in this study and previously6,11.

The observation that P-selectin is not required for enhanced microvascular thrombosis in endotoxemia is interesting, given findings that P-selectin mediates endotoxin-induced platelet-microvessel recruitment7 as well as the procoagulant activity associated with its soluble form17. The results appear to contradict previous studies showing that recruitment of platelets to inflamed microvessels in endotoxemia (in the absence of light/dye-injury) depend on adherent leukocytes, primarily neutrophils5,6. However, we showed recently that neutrophils were not required for LPS-induced enhancement of microvascular thrombosis in mouse cremaster venules6. Further, the magnitude of leukocyte-dependent platelet adhesion in mouse cremaster venules was estimated to result in ∼2% of endothelial surface covered by platelets6, likely having a minimal contribution to light/dye-induced occlusive thrombi. Of interest, Falati et al. described a role for P-selectin in a laser-induced model of microvascular thrombosis15, via PSGL-1 and tissue factor-bearing microparticles. In that report, P-selectin-deficient mice had impaired deposition of tissue factor and fibrin into developing thrombi, although platelet recruitment appeared comparable. The data shown in Figure 1 in P-selectin-deficient and WT mice suggest that P-selectin does not appear to play a prominent role in thrombosis in the present model and may reflect differences in thrombotic mechanisms between light/dye- and laser-induced models of endothelial injury, as suggested previously19. In our experiments, we used P-selectin-deficient mice that were backcrossed for 10 generations onto a C57BL6/J background33, and subsequently the strain has been maintained by homozygote breeding. While a 20% lower LPS dose was required for successful experimentation in these mice, we cannot conclude that absence of P-selectin enhances susceptibility to LPS based solely on these observations. A more thorough dose-response evaluation of the systemic responses to LPS in both P-selectin-deficient and littermate controls seems warranted to fully address this question. However, the data shown in Figure 1 demonstrate that P-selectin is not required for the enhanced microvascular thrombosis induced by LPS.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate a differential role of VWF and P-selectin in microvascular thrombosis in endotoxemia in a light/dye-induced model in mouse cremaster venules. The findings support an important role for VWF in the endotoxin-induced enhancement of thrombosis, which is independent of P-selectin. The influence of VWF on microvascular thrombosis in clinical sepsis remains to be clarified.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL-079368 (R.E.R.), EY-017120 (A.R.B.), EY-018239 (R.E.R. & A.R.B), and a Merit Review grant from The Department of Veterans Affairs (R.E.R.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an un-copyedited author manuscript that was accepted for publication in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, copyright The American Heart Association. This may not be duplicated or reproduced, other than for personal use or within the “Fair Use of Copyrighted Materials” (section 107, title 17, U.S. Code) without prior permission of the copyright owner, The American Heart Association. The final copyedited article, which is the version of record, can be found at Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. The American Heart Association disclaims any responsibility or liability for errors or omissions in this version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the National Institutes of Health or other parties.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aird WC. The role of the endothelium in severe sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Blood. 2003;101:3765–3777. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suffredini AF, Fromm RE, Parker MM, Brenner M, Kovacs JA, Wesley RA, Parrillo JE. The cardiovascular response of normal humans to the administration of endotoxin. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:280–287. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908033210503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pernerstorfer T, Stohlawetz P, Hollenstein U, Dzirlo L, Eichler HG, Kapiotis S, Jilma B, Speiser W. Endotoxin-induced activation of the coagulation cascade in humans: effect of acetylsalicylic acid and acetaminophen. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2517–2523. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.10.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerwinka WH, Cooper D, Krieglstein CF, Ross CR, McCord JM, Granger DN. Superoxide mediates endotoxin-induced platelet-endothelial cell adhesion in intestinal venules. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H535–H541. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00311.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rumbaut RE, Bellera RV, Randhawa JK, Shrimpton CN, Dasgupta SK, Dong JF, Burns AR. Endotoxin enhances microvascular thrombosis in mouse cremaster venules via a TLR4-dependent, neutrophil-independent mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1671–1679. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00305.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katayama T, Ikeda Y, Handa M, Tamatani T, Sakamoto S, Ito M, Ishimura Y, Suematsu M. Immunoneutralization of glycoprotein Ibalpha attenuates endotoxin-induced interactions of platelets and leukocytes with rat venular endothelium in vivo. Circ Res. 2000;86:1031–1037. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.10.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman ML, Way BA, Irwin JW. The inflammatory response to endotoxin. J Pathol. 1979;128:7–14. doi: 10.1002/path.1711280103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaub RG, Ochoa R, Simmons CA, Lincoln KL. Renal microthrombosis following endotoxin infusion may be mediated by lipoxygenase products. Circ Shock. 1987;21:261–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor FBJ. Staging of the pathophysiologic responses of the primate microvasculature to Escherichia coli and endotoxin: examination of the elements of the compensated response and their links to the corresponding uncompensated lethal variants. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S78–S89. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anthoni C, Russell J, Wood KC, Stokes KY, Vowinkel T, Kirchhofer D, Granger DN. Tissue factor: a mediator of inflammatory cell recruitment, tissue injury, and thrombus formation in experimental colitis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1595–1601. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McEver RP, Beckstead JH, Moore KL, Marshall-Carlson L, Bainton DF. GMP-140, a platelet alpha-granule membrane protein, is also synthesized by vascular endothelial cells and is localized in Weibel-Palade bodies. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:92–99. doi: 10.1172/JCI114175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper D, Chitman KD, Williams MC, Granger DN. Time-dependent platelet-vessel wall interactions induced by intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G1027–G1033. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00457.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padilla A, Moake JL, Bernardo A, Ball C, Wang Y, Arya M, Nolasco L, Turner N, Berndt MC, Anvari B, Lopez JA, Dong JF. P-selectin anchors newly released ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers to the endothelial cell surface. Blood. 2004;103:2150–2156. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falati S, Liu Q, Gross P, Merrill-Skoloff G, Chou J, Vandendries E, Celi A, Croce K, Furie BC, Furie B. Accumulation of tissue factor into developing thrombi in vivo is dependent upon microparticle P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 and platelet P-selectin. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1585–1598. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merten M, Chow T, Hellums JD, Thiagarajan P. A new role for P-selectin in shear-induced platelet aggregation. Circulation. 2000;102:2045–2050. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.17.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andre P, Hartwell D, Hrachovinova I, Saffaripour S, Wagner DD. Pro-coagulant state resulting from high levels of soluble P-selectin in blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13835–13840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250475997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eppihimer MJ, Wolitzky B, Anderson DC, Labow MA, Granger DN. Heterogeneity of expression of E- and P-selectins in vivo. Circ Res. 1996;79:560–569. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rumbaut RE, Slaff DW, Burns AR. Microvascular thrombosis models in venules and arterioles in vivo. Microcirculation. 2005;12:259–274. doi: 10.1080/10739680590925664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sporn LA, Chavin SI, Marder VJ, Wagner DD. Biosynthesis of von Willebrand protein by human megakaryocytes. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1102–1106. doi: 10.1172/JCI112064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadler JE. Biochemistry and genetics of von Willebrand factor. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:395–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michaux G, Pullen TJ, Haberichter SL, Cutler DF. P-selectin binds to the D′-D3 domains of von Willebrand factor in Weibel-Palade bodies. Blood. 2006;107:3922–3924. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schorer AE, Moldow CF, Rick ME. Interleukin 1 or endotoxin increases the release of von Willebrand factor from human endothelial cells. Br J Haematol. 1987;67:193–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1987.tb02326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reidy MA, Chopek M, Chao S, McDonald T, Schwartz SM. Injury induces increase of von Willebrand factor in rat endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 1989;134:857–864. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernardo A, Ball C, Nolasco L, Moake JF, Dong JF. Effects of inflammatory cytokines on the release and cleavage of the endothelial cell-derived ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers under flow. Blood. 2004;104:100–106. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto K, de Waard V, Fearns C, Loskutoff DJ. Tissue distribution and regulation of murine von Willebrand factor gene expression in vivo. Blood. 1998;92:2791–2801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reiter RA, Varadi K, Turecek PL, Jilma B, Knobl P. Changes in ADAMTS13 (von-Willebrand-factor-cleaving protease) activity after induced release of von Willebrand factor during acute systemic inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:554–558. doi: 10.1160/TH04-08-0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moake JL, Rudy CK, Troll JH, Weinstein MJ, Colannino NM, Azocar J, Seder RH, Hong SL, Deykin D. Unusually large plasma factor VIII:von Willebrand factor multimers in chronic relapsing thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1432–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198212023072306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ono T, Mimuro J, Madoiwa S, Soejima K, Kashiwakura Y, Ishiwata A, Takano K, Ohmori T, Sakata Y. Severe secondary deficiency of von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease (ADAMTS13) in patients with sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation: its correlation with development of renal failure. Blood. 2006;107:528–534. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen TC, Liu A, Liu L, Ball C, Choi H, May WS, Aboulfatova K, Bergeron AL, Dong JF. Acquired ADAMTS-13 deficiency in pediatric patients with severe sepsis. Haematologica. 2007;92:121–124. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bullard DC, Qin L, Lorenzo I, Quinlin WM, Doyle NA, Bosse R, Vestweber D, Doerschuk CM, Beaudet AL. P-selectin/ICAM-1 double mutant mice: acute emigration of neutrophils into the peritoneum is completely absent but is normal into pulmonary alveoli. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1782–1788. doi: 10.1172/JCI117856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denis C, Methia N, Frenette PS, Rayburn H, Ullman-Cullere M, Hynes RO, Wagner DD. A mouse model of severe von Willebrand disease: defects in hemostasis and thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9524–9529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Rumbaut RE, Burns AR, Smith CW. Platelet response to corneal abrasion is necessary for acute inflammation and efficient re-epithelialization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4794–4802. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rumbaut RE, Randhawa JK, Smith CW, Burns AR. Mouse cremaster venules are predisposed to light/dye-induced thrombosis independent of wall shear rate, CD18, ICAM-1, or P-selectin. Microcirculation. 2004;11:239–247. doi: 10.1080/10739680490425949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis MJ. Determination of volumetric flow in capillary tubes using an optical Doppler velocimeter. Microvasc Res. 1987;34:223–230. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(87)90055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chauhan AK, Walsh MT, Zhu G, Ginsburg D, Wagner DD, Motto DG. The combined roles of ADAMTS13 and VWF in murine models of TTP, endotoxemia, and thrombosis. Blood. 2008;111:3452–3457. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konstantinides S, Ware J, Marchese P, Almus-Jacobs F, Loskutoff DJ, Ruggeri ZM. Distinct antithrombotic consequences of platelet glycoprotein Ibalpha and VI deficiency in a mouse model of arterial thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:2014–2021. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lominadze D, Saari JT, Miller FN, Catalfamo JL, Schuschke DA. Von Willebrand factor restores impaired platelet thrombogenesis in copper-deficient rats. J Nutr. 1997;127:1320–1327. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.7.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubois C, Panicot-Dubois L, Gainor JF, Furie BC, Furie B. Thrombin-initiated platelet activation in vivo is vWF independent during thrombus formation in a laser injury model. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:953–960. doi: 10.1172/JCI30537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thorlacius H, Vollmar B, Seyfert UT, Vestweber D, Menger MD. The polysaccharide fucoidan inhibits microvascular thrombus formation independently from P- and L-selectin function in vivo. Eur J Clin Invest. 2000;30:804–810. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2000.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]