Abstract

Background

It is unknown whether health-related media stories reach diverse older adults and influence advance care planning (ACP).

Objective

To determine exposure to media coverage of Terri Schiavo (TS) and its impact on ACP.

Design and Participants

Descriptive study of 117 English/Spanish-speakers, aged ≥50 years (mean 61 years) from a county hospital, interviewed six months after enrollment into an advance directive study.

Measurements

We assessed whether participants had heard of TS and subject characteristics associated with exposure. We also asked whether, because of TS, subjects engaged in ACP.

Main Results

Ninety-two percent reported hearing of TS. Participants with adequate literacy were more likely than those with limited literacy to report hearing of TS (100% vs. 79%, < .001), as were participants with ≥ a high school vs. < high school education (97% vs. 82%, = .004), and English vs. Spanish-speakers (96% vs. 85%, = .04). Because of TS, many reported clarifying their own goals of care (61%), talking to their family/friends about ACP (66%), and wanting to complete an advance directive (37%).

Conclusions

Most diverse older adults had heard of TS and reported that her story activated them to engage in ACP. Media stories may provide a powerful opportunity to engage patients in ACP and develop public health campaigns.

KEY WORDS: mass media, public health, advance care planning, health literacy, vulnerable populations

INTRODUCTION

Media health campaigns and direct-to-consumer advertising can increase health knowledge and activate patients to seek care and change behavior,1,2 although less consistently among minority groups.1,3,4 Unlike health campaigns, news coverage of health-related stories, such as Terri Schiavo’s (TS), do not always have a clear health-related message.5,6 However, just as the “Katie Couric effect” increased colon cancer screening, health-related stories may activate patients for behavior change.1,7

TS was a 41-year-old woman who was in a persistent vegetative state after suffering a cardiac arrest in 1991. After a prolonged legal battle, her feeding tube was removed on March 18, 2005 and she died on March 31.8 There was extensive news coverage of TS’s story while we were administering a follow-up questionnaire for an advance directive preference study among English-speaking and Spanish-speaking older adults. Therefore, we took the opportunity to determine the reach of the media coverage of TS’s story within our sample. Given historically low penetration of health-related information among minorities and patients of lower socioeconomic status,3,4 we assessed the influence of literacy, education, and language on the reach of TS’s story. We also explored whether hearing about TS influenced engagement in advance care planning (ACP).

METHODS

In this descriptive study, participants were part of an on-going advance directive preference study.9 Subjects were recruited between August and December 2004, using convenience sampling, from an urban, county general medicine clinic in San Francisco. Participants were eligible if they were 50 years of age or older and reported fluency in English or Spanish. Participants were excluded if they had dementia, or were deaf, delirious, or acutely ill.

In February 2005, we began administering a six-month follow-up telephone questionnaire to assess whether participants had engaged in ACP. Because of the concurrent TS media coverage, on April 13, 2005 we added six questions concerning TS to our questionnaire. This study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

To assess the reach of TS’s story we asked “Have you heard about Terri Schiavo? She was the woman with brain damage from Florida who recently had her feeding tube removed and she died?”

We then asked participants who reported having heard of TS whether her story motivated them to clarify their values and become “more sure” of their own treatment wishes. We also asked whether TS led participants to discuss their own health care wishes with their family or friends, to want to complete an advance directive, to discuss their health care wishes with physicians (excluding 32 participants who had not seen their doctor), or to complete an advance directive (excluding ten participants who had previously completed one). These questions were asked to capture multiple steps in the ACP process.10

We obtained self-reported age, race/ethnicity, gender, income, educational attainment, religiosity, and self-rated health. Personal end-of-life experience was defined as any previous personal or family/friend admittance to an ICU or having helped someone complete an advance directive. For multivariable analysis, we created a composite measure based on affirmative responses to any of these end-of-life indicators. We measured literacy using the short form Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults dichotomized into adequate literacy (scores > 22/36) and limited literacy (≤22/36).11 We searched the LexisNexis and English and Spanish television news archive databases with the search term “Terri Schiavo” to determine the height of both print and television TS media coverage and the time from the height of the coverage to the study interview (methods further described in Fig. 1).12–14

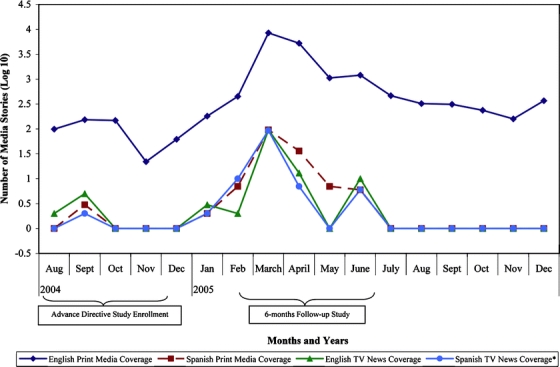

Figure 1.

Print and television media coverage of Terri Schiavo. Footnote: Because the impact of the TS case could have waned over time, we measured the number of days from the height of the TS media coverage until participants were interviewed. To estimate the height of the media coverage and determine its trajectory, we searched the LexisNexis database for all English news full-text articles and all major world publications in non-English (searching for Spanish publications) with the search term “Terri Schiavo”.12 We also searched the Vanderbilt University Television News Archives database, which included evening news coverage for all major English U.S. television news stations,13 and the archives database of Univision, a major U.S Spanish television station, using the search term “Terri Schiavo”. All print or television data where TS was mentioned were captured and categorized by month and year. * Results obtained from Univision™, one of the largest Spanish television stations in the U.S.

Data Analysis

The associations between subject characteristics and the reach of TS’s story were assessed with χ2 tests, Fisher’s exact tests, t-tests, and stepwise multivariate logistic regression. All subject characteristics associated with the outcome at < .05 were retained in the final multivariate model.

RESULTS

Due to the timing of TS’s story relative to our follow-up questionnaire for the advance directive preference study, 117/173 (68%) eligible subjects were asked additional questions about TS.

Demographic characteristics of participants are listed in Table 1. Participants were interviewed a mean of 72 days (range 43–134) after March 1, 2005, the date roughly corresponding to the accelerated phase of the TS media coverage (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics, = 117

| % or mean (±SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 61 years (±8) |

| Women | 53 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 20 |

| White, Hispanic (Latino) | 41 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 21 |

| Asian | 7 |

| Multi-racial/ethnic, Other | 11 |

| Income < $10,000/yr | 47 |

| Less than high school education | 38 |

| Limited Literacy* | 40 |

| Spanish-speaking | 39 |

| Very to extremely religious | 45 |

| Fair to poor self-rated health | 71 |

| Personal end-of-life experience | |

| Previously filled out an advance directive | 10 |

| Previously admitted to ICU | 33 |

| Had friends/family admitted to ICU | 58 |

| Helped others fill out an advance directive | 13 |

| Days interviewed since Terri Schiavo’s death | 72 (±18) |

† Literacy was assessed using the short form test of Functional Literacy in Adults (s-TOFHLA), a 36-item, timed reading comprehension test. Participants with scores ≤ 22 (possible range of 0–36) were considered to have limited literacy or an approximate reading level of ≤ 8th grade.

One hundred and seven participants (92%) reported hearing of TS. Participants with adequate literacy were more likely than those with limited literacy to hear of TS’s story (100% vs. 79%, < .001), as were subjects with ≥ a high school education versus < a high school education (97% vs. 82%, = .004). English speakers were also more likely to hear of TS’s story compared to Spanish-speakers (96% vs. 85%, = .04), as were participants who were < 65 years versus ≥ 65 years (97% vs. 86%, = .03). Only literacy was associated with an increased odds of hearing of TS’s story after stepwise multivariate analysis adjusted for age and language (OR 1.21 for every one-point increase in literacy score; 95% CI 1.07–1.37).

Among participants who had heard of TS ( = 107), a significant proportion reported that her story activated them to engage in ACP: 61% reported feeling more sure about the type of medical care they would want if they became sick or were near the end of their lives; 66% talked to their family or friends about what they would want done were they in TS’s situation; 37% reported wanting to fill out an advance directive; 8% talked to their doctor about ACP; and 3% completed an advance directive.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates the power of the mass media to reach a substantial portion of diverse older adults with health-related information. In this diverse older sample, almost all participants reported hearing about TS’s story. While the reach was lower for those with limited literacy, lower education, and Spanish-speakers, the vast majority of subjects in these groups reported hearing about her story.

There was also substantial engagement in ACP as a result of exposure to TS’s story among this diverse, socioeconomically vulnerable sample, populations who historically have had low rates of ACP engagement.15,16 Of subjects who reported being reached by the media, a majority felt “more sure” of their goals of care because of TS’s story, had discussed with family and friends what they would want were they in TS’s situation, and many wanted to fill out an advance directive. In contrast, very few subjects reported having spoken to their doctors or completing a written advance directive.

The substantial television coverage of TS may help explain both the reach of the TS case and its effects on ACP engagement. The broad reach of TS’s story may reflect the fact that a majority of older adults, regardless of literacy or education, obtain health-related information from television.17 The power of visual images may further explain why TS’s story resulted in substantial ACP engagement. A recent study found that video images of advanced Alzheimer’s disease activated patients to change their care preferences, especially among minorities and those of lower education and literacy.18

Low rates of discussions with clinicians and advance directive documentation may represent missed opportunities to harness the media coverage of TS to promote ACP. According to an Associated Press report, visits to the U.S. Living Will Registry and the Aging with Dignity websites resulted in over a 1000-fold increase in downloads of living wills at the time of TS’s death, and remained twice what they had been the year after her death.19 TS’s continued coverage in the media today suggests that her story may yet be a powerful tool to use in ACP campaigns.12,13

Because news stories can contain biased or inaccurate information,5,6 it is possible that some subjects may have misunderstood the facts or had misperceptions regarding how TS’s story should have been integrated into their own decision-making. Physicians may need to clarify and interpret health-related news stories, particularly among patient populations with historically high degrees of mistrust in the medical system.20

Limitations of this study include the inability to distinguish activation in ACP due to TS’s story or due to the added effect of prior exposure to an advance directive (although we asked subjects to focus solely on the effect of TS’s story). Additional limitations include compromised generalizability due to completing the study in one region of the country, limited power due to the small sample size, and the lack of information about patient/provider language discordance, which may have contributed to low rates of ACP for some participants.

In conclusion, we found that a majority of diverse older adults reported hearing of the Terri Schiavo story and that her case activated them to engage in ACP. Although nearly all subjects had heard of TS, the reach of the media was less comprehensive for subjects with limited literacy and for Spanish-speakers. Media stories, such as the TS case, may represent unique opportunities for clinicians to initiate difficult discussions about ACP, clarify misperceptions of media stories, elicit patients’ values for care, provide context to help patients integrate the information into their own decision-making, and may be used to develop ACP campaigns.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Sudore and this study were supported by the American Medical Association Foundation; the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging K07 AG000912; the National Institutes of Health Research Training in Geriatric Medicine Grant: AG000212; the Pfizer Fellowship in Clear Health Communication; the NIH Diversity Investigator Supplement 5R01AG023626–02; and an NIA Mentored Clinical Scientist Award K-23 AG030344–01. Dr. Schillinger was supported by an NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1 RR024131.

The abstract of this paper was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine conference in April 2007.

Conflict of Interest Statement Dr. Sudore is funded in part by the Pfizer Foundation through the Clear Health Communication Fellowship. The Pfizer foundation was not involved in the design, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of the results, or the writing of this manuscript. No other authors report a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Grilli R, Ramsay C, Minozzi S. Mass media interventions: effects on health services utilisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002(1):CD000389. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Feldman MD, et al. Influence of patients’ requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(16):1995–2002. Apr 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Mosca L, Mochari H, Christian A, et al. National study of women’s awareness, preventive action, and barriers to cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2006;113:525–34. Jan 31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Frates J, Bohrer GG, Thomas D. Promoting organ donation to Hispanics: the role of the media and medicine. J Health Commun. 2006;11(7):683–98. Oct-Nov. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Moynihan R, Bero L, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Coverage by the news media of the benefits and risks of medications. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(22):1645–50. Jun 1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. News media coverage of screening mammography for women in their 40s and tamoxifen for primary prevention of breast cancer. JAMA. 2002;287(23):3136–42. Jun 19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Cram P, Fendrick AM, Inadomi J, Cowen ME, Carpenter D, Vijan S. The impact of a celebrity promotional campaign on the use of colon cancer screening: the Katie Couric effect. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(13):1601–5. Jul 14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Annas GJ. “Culture of life” politics at the bedside-the case of Terri Schiavo. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(16):1710–15. Apr 21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Barnes DE, et al. An advance directive redesigned to meet the literacy level of most adults: a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69(1–3):165–95. Dec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Sudore RL, Schickedanz AD, Landefeld CS, et al. Engagement in multiple steps of the advance care planning process: a descriptive study of diverse older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):1006–13, Apr 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38(1):33–42. Sep. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lexisnexis Academic Database. Search terms: “Terri Schiavo” for all English, full-text articles within the Major U.S. and World Publications search category and all non-English full-text publications within the major world publications search category. http://academic.lexisnexis.com. Accessed June 27, 2008.

- 13.Vanderbilt Television News Archives. Search Terms: “Terri Schiavo” for all evening news coverage for ABC, CBS, NBC, CNN, PBS, FOX, MSNBC,CSPAN, and CNBC. http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu. Accessed June 27, 2008.

- 14.Eisemann M, Richter J. Relationships between various attitudes towards self-determination in health care with special reference to an advance directive. J Med Ethics. 1999;25(1):37–41. Feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Hofmann JC, Wenger NS, Davis RB, et al. Patient preferences for communication with physicians about end-of-life decisions. SUPPORT investigators. Study to understand prognoses and preference for outcomes and risks of treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(1):1–12. Jul 1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hanson LC, Rodgman E. The use of living wills at the end of life. A national study. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(9):1018–22. May 13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Weiss BD, Reed RL, Kligman EW. Literacy skills and communication methods of low-income older persons. Patient Educ Couns. 1995;25(2):109–19. May. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK. Health literacy, health inequality and a just healthcare system. Am J Bioeth. 2007;7(11):5–10. Nov. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Stacy M. More living wills is lasting legacy of Schiavo drama. The Associated Press State and Local Wire, March 20, 2006.

- 20.Smith WR, Betancourt JR, Wynia MK, et al. Recommendations for teaching about racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):654–65. Nov 6. [DOI] [PubMed]