Abstract

Drug-induced hepatotoxicity is well recognized but can cause some diagnostic problems, particularly if not previously reported. The present case involves a 22-year-old male who presented with jaundice and elevated liver enzymes after a course of cefdinir (Omnicef®) for streptococcal pharyngitis. A diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury was suspected but a liver biopsy was required after his jaundice worsened despite cessation of the presumed offending agent. A short course of steroids was initiated and eventually the jaundice resolved. This case highlights the need to suspect medication-induced liver injury in cases of jaundice, even if not previously reported. In addition, it illustrates the potential for adverse outcomes in situations where antibiotics are used inappropriately or where first line antibiotics are not used for routine infections. We report a case of a young male who developed jaundice associated with cefdinir use with pathological confirmation of moderate cholestasis with portal and lobular mixed inflammation and focal bile duct injury consistent with drug-induced liver injury.

KEY WORDS: hepatotoxicity, cholestasis, cefdinir

INTRODUCTION

Cefdinir (Omnicef®) is an extended spectrum third generation cephalosporin approved by the Food and Drug Association in December 1997, for use in otitis media, soft tissue infections and respiratory tract infections, such as community-acquired pneumonia, bronchitis and acute sinusitis, caused by several gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria.1 It is a generally well tolerated antibiotic, with most adverse effects being mild and self-limiting. Common adverse effects of cefdinir that have been reported include gastrointestinal disturbances,1–3 such as diarrhea and nausea in 18% of people who reported adverse events in a clinical trial, headache, vaginitis, and rash.2 Abnormal laboratory values that were observed in the clinical trials more frequently include urine leukocytes, proteinuria, elevated gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGTP) and lymphocyte levels and microhematuria.1 There have been no published reports of hepatotoxicity associated with cefdinir.

We report a case of a young male who developed jaundice associated with cefdinir use with pathological confirmation of moderate cholestasis with portal and lobular mixed inflammation and focal bile duct injury consistent with drug-induced liver injury. It highlights the potential for adverse events when antibiotics are used injudiciously.

Case Report

A 22-year-old Caucasian male was admitted with a five-day history of painless jaundice and pruritus. His past medical history was only remarkable for an appendectomy and a recent presumptive diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis by his primary care physician that was treated with a 10-day course of oral cefdinir 300 mg twice a day, which he completed five days prior to presentation. The reason for the choice of antibiotic was unclear.

One month prior he had returned from a 3-month trip to Europe where he had unprotected sexual intercourse with men. He denied significant alcohol or recreational drug use and was not taking any non-prescription or herbal medications. There was no history of sexually transmitted diseases. He had no relevant family history.

Physical examination was remarkable for morbid obesity (body mass index of 45 kg/m2), scleral icterus and jaundice. Abdominal examination demonstrated a soft, obese abdomen without hepatosplenomegaly.

Laboratory evaluations revealed a total bilirubin of 15.7 mg/dl, conjugated bilirubin of 12.5 mg/dl, ALT of 96 IU/L, AST of 66 IU/L, ALP of 175 IU/L, and GGTP of 77 IU/L. His liver synthetic function, renal function and hemoglobin remained normal. Urine toxicology screen was negative and serum acetaminophen level was undetectable. Initially his international normalized ratio (INR) was normal but rose to 1.5 three weeks after presentation, and his total bilirubin increased to 41.4 mg/dl and conjugated bilirubin to 25.1 mg/dl, while AST and ALT levels normalized. Serological markers for acute viral hepatitis were negative with a negative anti-hepatitis A IgM, negative anti-hepatitis B core IgM and negative hepatitis B surface antigen. Hepatitis C and HIV antibodies were negative. Liver ultrasound was unremarkable. Markers for autoimmune hepatitis and metabolic liver disease including anti-nuclear antibody and smooth muscle antibody were negative with normal serum immunoglobulins. Ceruloplasmin, alpha-1-antitrypsin and ferritin levels were all in the normal range.

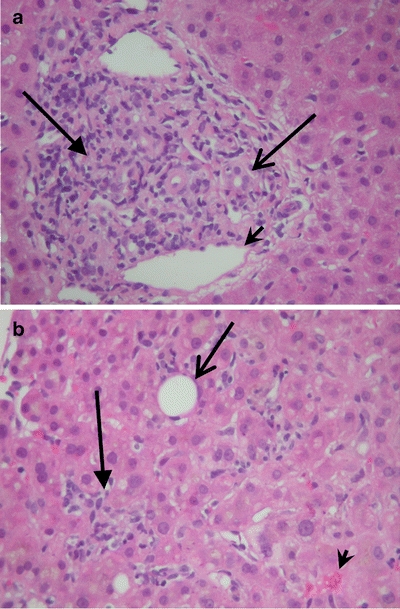

Due to the worsening hyperbilirubinemia, a liver biopsy was performed five days after presentation (Fig. 1 a,b). There was moderate cholestasis with portal and lobular mixed inflammation and focal bile duct injury, consistent with drug-induced liver injury. Histological features typical for autoimmune hepatitis were not seen and immunochemical stains for CMV, EBV, herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, hepatitis B surface and core antigens were negative.

Figure 1.

a Liver biopsy demonstrating mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the portal area with neutrophils, plasma cells, lymphocytes and occasional eosinophils. There are areas of bile ductular injury. (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 200x magnification). (Arrow = inflammatory cells in portal tract, open arrow = bile duct, arrowhead = portal vein). b Liver biopsy demonstrating mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the lobule with mild central venulitis and moderate hepatocellular and canalicular cholestasis. (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 200x magnification). (Arrow = inflammatory cells in lobule, open arrow = central vein, arrowhead = bile plugs).

The patient’s pruritus persisted despite symptomatic treatment with cholestyramine and hydroxyzine and a short prednisone taper was initiated three weeks after initial presentation. Within seven weeks from admission, his symptoms had resolved and the bilirubin levels returned to normal (Table 1).

Table 1.

Liver Injury Tests During the Patient’s Clinical Course

| Days from presentation | Total bilirubin (mg/dl) normal 0.3–1.5 | Direct bilirubin (mg/dl) normal 0.0–0.3 | AST (IU/L) normal 10–40 | ALT (IU/L) normal 10–40 | ALP (IU/L) normal 40–125 | GGTP (IU/L) normal 10–40 | INR normal 0.9–1.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission | 15.7 | 12.5 | 66 | 96 | 175 | 77 | 1.0 |

| 2 | 15.8 | 12.4 | 57 | 87 | 148 | 66 | |

| 3 | 16.7 | 56 | 79 | 145 | 58 | ||

| 7 | 26.9 | 22.5 | 55 | 73 | 165 | 45 | 1.1 |

| 9 | 32.8 | 60 | 79 | 190 | 42 | 1.4 | |

| 15 | 31.9 | 20.4 | 48 | 57 | 194 | 39 | 1.5 |

| 22 (Started prednisone) | 41.4 | 25.1 | 48 | 57 | 191 | 41 | 1.3 |

| 30 | 25.9 | 18.0 | 60 | 103 | 200 | 57 | 1.3 |

| 36 | 14.6 | 7.2 | 83 | 185 | 151 | 69 | 1.0 |

| 42 | 8.8 | 3.4 | 79 | 192 | 153 | 144 | 0.9 |

| 56 | 2.7 | <0.1 | 87 | 266 | 144 | 157 | 0.9 |

| 70 | 1.2 | <0.1 | 32 | 67 | 92 | 118 | 1.0 |

| 77 | 0.8 | <0.1 | 24 | 45 | 93 | 99 | 1.0 |

DISCUSSION

This case report of hepatotoxicity associated with cefdinir illustrates the potential for adverse outcomes in situations where first line antibiotics are not used for routine infections. Acute pharyngitis is a commonly encountered condition in primary care and antibiotics can be used if group A streptococcal infection is suspected, since the duration of illness can be shortened and potential complications may be avoided. Penicillin is the drug of choice, but guidelines suggest avoiding antibiotic use in most cases unless throat culture is positive.4 Studies demonstrate that as well as inappropriate antibiotic use, unnecessary broader spectrum agents are often used.5 The only indication to use a third generation cephalosporin would be if gonococcal pharyngitis was suspected and ceftriaxone intramuscularly is recommended as first line.6

Drug-induced hepatic injury is under-recognized but is seen with a variety of medications and can present in a spectrum ranging from asymptomatic biochemical abnormalities to jaundice or acute liver failure.7,8 There are only a few case reports implicating other cephalosporins as the cause of isolated hyperbilirubinemia in adults. Our patient was treated with cefdinir for his presumed streptococcal pharyngitis. After completion of the antibiotics, he developed jaundice and pruritus that was treated with bile acid binders and antihistamines; however his symptoms persisted and the patient was placed on a course of oral corticosteroids. The close temporal relationship between the start of the cefdinir and the onset of the symptoms, and the lack of any other potentially hepatototoxic drugs, combined with the biopsy findings and lack of biliary dilation on imaging, strongly suggest that cefdinir caused the development of hepatotoxicity in this patient.

Interestingly, the patient’s bilirubin level was markedly elevated in the setting of only mildly elevated cholestatic enzymes but still fulfilled criteria for cholestatic injury since the ALT/ALP ratio (defined as the ALT/upper limit of normal ALT divided by the ALP/upper limit of normal ALP) was less than or equal to two.9 His mildly elevated INR was likely a reflection of decreased vitamin K absorption rather than impaired liver synthetic function given the relative paucity of hepatocyte injury on biopsy and only mildly elevated ALT.

The patient had other risk factors for hepatotoxicity. Hepatitis B was a concern when the patient first presented due to the history of unprotected intercourse with men, but serology for hepatitis B was negative. Undiagnosed HIV infection and even AIDS was a possibility given the patient’s risk factors for sexually transmitted disease. Hence the differential diagnosis included opportunistic infections, particularly atypical mycobacteria, cytomegalovirus and AIDS cholangiopathy.

The patient’s morbid obesity raised the possibility of an acute insult on the background of underlying fatty liver disease. However his liver biopsy demonstrated less than 5% steatosis. First presentation of autoimmune or metabolic liver disease, such as Wilson disease or autoimmune hepatitis, remained in the differential diagnosis, but serology for these causes of liver disease were negative and the liver biopsy confirmed drug-induced cholestasis, most consistent with the hepatocanalicular type, with prominent cholestasis but also inflammatory activity.10

Cefdinir is an oral third-generation cephalosporin that is highly active against many gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. It is generally well tolerated with minimal adverse effects. The most common adverse effect is gastrointestinal disturbances, such as diarrhea and nausea.1,3. Cefdinir is not metabolized appreciably and the activity is primarily due to the parent drug. It is renally eliminated and a small portion of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine. The pharmacokinetics of cefdinir have not been studied in patients with hepatic dysfunction, because the drug does not undergo hepatic metabolism and it is not expected to alter its pharmacokinetic profile.1,2 Niwa et al. concluded that cefdinir was not metabolized by human hepatic microsomes; thus it should not have significant interactions with other drugs that were metabolized by this pathway. 11

There have been several cases of hepatotoxicity related to other cephalosporins. Eggleston et al. documented two cases of jaundice in patients who were taking cefamandole and cephalothin, with resolution of the symptoms when the antibiotics were discontinued.12 Ceftriaxone, a third-generation cephalosporin, has been associated with biliary sludge and hyperbilirubinemia.13 Cholestatic jaundice was also associated with cephalexin and cefazolin.14,15 A newer third-generation cephalosporin, cefproxil, similar to cefdinir in its pharmacokinetics and adverse effect profile has been associated with hepatitis.16 Cephalosporins are not typically known to be hepatotoxic; therefore the mechanism continues to be poorly understood, although hypersensitivity has been postulated.17 In all these cases, jaundice was mild and self-limited upon the discontinuation of the therapy, though it took several weeks to improve. Other drugs causing cholestatic injury can interfere with hepatocyte secretion of bile constituents and the effect is characteristic and typically dose-related as seen with chlorpromazine, nafcillin, rifampin, estradiol and erythromycin estolate.9

In comparison with other cases of cephalosporin-induced jaundice, our patient had a similar but more prolonged course. The reasons for this are unclear but may have been related to his morbid obesity, and hence possible metabolic syndrome.

In conclusion, clinicians should be aware of the risk of hepatotoxicity with the use of cefdinir, and recognize that injudicious use of antibiotics can lead to significant adverse events.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- EBV

Epstein–Barr virus

- GGTP

gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase

References

- 1.Food and Drug Admistration. Cefdinir. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/SAFETY/2004/sep_PI/Omicef_PI.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2008.

- 2.Perry CM, Scott LJ. Cefdinir: A review of its use in the management of mild-to-moderate bacterial infections. Drugs. 2004;64:1438–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Arguedas A, Dagan R, Leibovitz E, Hoberman A, Pichichero M, Paris M. A multicenter, open label, double tympanocentesis study of high dose cefdinir in children with acute otitis media at high risk of persistent or recurrent infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:211–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.McIsaac WJ, Kellner JD, Aufricht P, Vanjaka A, Low DE. Empirical validation of guidelines for the management of pharyngitis in children and adults. JAMA. 2004;291:1587–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Linder JA, Stafford RS. Antibiotic treatment of adults with sore throat by community primary care physicians: a national survey, 1989–1999. JAMA. 2001;286:1181–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–94. [PubMed]

- 7.Sgro C, Clinard F, Ouazir K, Chanay H, Allard C, Guilleminet C, Lenoir C, Lemoine A, Hillon P. Incidence of drug-induced hepatic injuries: a French population-based study. Hepatology. 2002;36:451–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Lee WM. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:474–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kaplowitz N. Drug- induced liver injury. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(Suppl 2):S44–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Larrey D. Drug-induced liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2000;321 (Suppl):77–88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Niwa T, Shiraga T, Hashimoto T, Kagayama A. Effect of Cefixime and Cefdinir, Oral Cephalosporins, on Cytochrome P450 Activities in Human Hepatic Microsomes. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:97–9. Jan. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Eggleston SM, Belandres MM. Jaundice Associated with Cephalosporin therapy. Drug Intell Clin Pharmacy. 1985;19:553–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Bickford CL, Spencer AP. Biliary Sludge and Hyperbilirubinemia Associated with Ceftriaxone in an Adult: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25(10):1389–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Skoog S, Smyrk T, Talwalker J. Cephalexin-induced cholestatic hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:833. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Pacik PT. Augmentation mammaplasty: postoperative cephalosporin-induced hepatitis. Plastic Reconstruct Surg. 2007;119(3):1136–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Bilici A, Karaduman M, Cankir Z. A rare case of hepatitis associated with cefprozil therapy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39:190–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Lambert DH. Cephalosporin hepatitis. Anesth Analg. 1980;59:806. [DOI] [PubMed]