Abstract

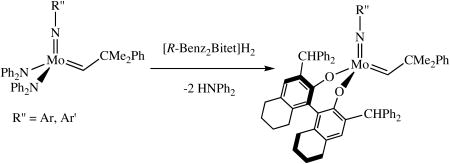

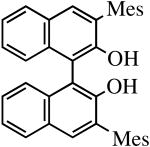

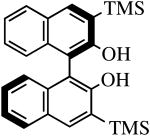

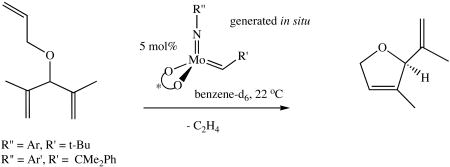

We have found that Mo(NAr)(CHR′)(NPh2)2 (R′ = t-Bu or CMe2Ph) and Mo(NAr′)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 (Ar = 2,6-i-Pr2C6H3; Ar′ = 2,6-Me2C6H3) can be prepared through addition of two equivalents of LiNPh2 to Mo(NR″)(CHR′)(OTf)2(dme) species (R″ = Ar or Ar′ dme = 1,2-dimethoxyethane), although yields are low. A high yield route consists of addition of LiNPh2 to bishexafluro-t-butoxide species. An X-ray structure of Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 reveals that the two diphenylamido groups are oriented in a manner that allows an 18 electron count to be achieved. The diphenylamido complexes react readily with t-BuOH and (CF3)2MeCOH, but not readily with the sterically demanding biphenol H2[Biphen] (Biphen2- = 3,3′-Di-t-butyl-5,5′,6,6′-tetramethyl-1,1′-Biphenyl-2,2′-diolate). The diphenylamido complexes do react with various 3,3′-disubstituted binaphthols to yield binaphtholate catalysts that can be prepared in situ and employed for a simple asymmetric ring-closing metathesis reaction. In several cases conversions and enantioselectivities were comparable to reactions in which isolated catalysts were employed.

Introduction

We have been searching for methods of synthesizing Mo(NR)(CHR′)(OR″)2 species (or related species that contain enantiomerically pure biphenolate or binaphtholate ligands1) in situ. The main reason is that an increasing number of applications (e.g., asymmetric olefin metathesis1) require an evaluation of many catalysts having different combinations of imido and alkoxide ligands for a given chemical transformation and therefore the synthesis, isolation, and storage of many catalysts. It also would be desirable to synthesize well-defined supported catalysts (e.g., on partially dehydroxylated silica2). We have reported the synthesis of catalysts in situ in a manner that is essentially the same as that employed to prepare and isolate each catalyst, i.e., addition of the potassium salt of a biphenolate or a binaphtholate to a Mo(NR)(CHR′)(OTf)2(dme) species in THF.3 However, the most attractive goal would be to prepare a Mo(NR)(CHR′)X2 precursor that could be transformed readily into Mo(NR)(CHR′)(OR″)2 (or a related biphenolate or binaphtholate species) simply through addition of the monoalcohol or diol to the Mo(NR)(CHR′)X2 precursor. This method would require that the HX product of this reaction not interfere to any significant degree with subsequent reactions that involve Mo(NR)(CHR′)(OR″)2, and also not react with any organic species in the reaction. A wide variety of Mo(NR)(CHR′)(OR″)2 catalysts then could be generated in situ and evaluated relatively rapidly. We first focused on species in which X = CH2CMe3, but we found that Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(CH2-t-Bu)2 and related species react with only one equivalent of alcohols to yield complexes of the type Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(CH2-t-Bu)(OR), or precursors to them, Mo(NAr)(CH2-t-Bu)3(OR) spercies,4 even on silica surfaces.5 Although Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(CH2-t-Bu)(OR) and related species are surprisingly active catalysts and are of fundamental interest in their own right, we had to reevaluate our approach to bisalkoxide precursors.

Amido groups have been employed extensively in transition metal chemistry, especially early metal chemistry, and it is well known that they often can be protonated readily.6 Some high oxidation state Mo chemistry reported by Cummins is especially noteworthy. He and his group have prepared trisalkoxide complexes of the type Mo(X)(OAd)3 through addition of three equivalents of adamantanol to Mo(X)[N(i-Pr)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]3 species (X = CCH2SiMe37, N8, P9). Moore has extended this approach in order to prepare alkylidyne catalysts of molybdenum for the metathesis of alkynes.10 Therefore we turned to the possibility of preparing bisamido catalyst precursors, Mo(NR)(CHR′)(amido)2.

The only known M(NR)(CHR′)(amido)2 (M = Mo or W) species is W(NAr)(CHEt)(NPh2)2, which was prepared in 73% yield as golden-orange crystals upon treating W(CHEt)(NAr)[OCMe(CF3)2]2(3-hexene)0.8 with 2 equivalents of LiNPh2.11 (W(CHEt)(NAr)[OCMe(CF3)2]2(3-hexene)0.8 is believed to be a mixture of a propylidene complex and a triethylmetallacyclobutane complex.) Complexes that contain chelating (diamido) ligands are known, e.g., molybdenum complexes that contain a N,N′-disubstituted-2,2′-bisamido-1,1′-binaphthyl ligand.12 Boncella has isolated M(NPh)(CH-t-Bu)[o-(Me3SiN)2C6H4](PMe3) (M = Mo, W) species as the products of the reactions between M(NPh)(CH2-t-Bu)2[o-(Me3SiN)2C6H4] (M = Mo, W) and 5 equivalents of PMe3, and other chemistry of both Mo and W compounds that contain the [o-(Me3SiN)2C6H4]2- diamido ligand has been published.13,14 In view of the existence of W(NAr)(CHEt)(NPh2)2 we therefore first sought to prepare Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(NPh2)2 and to employ it as a precursor for the in situ synthesis of asymmetric metathesis catalysts. This paper reports the results of these and related studies.

Results

Synthesis of bisdiphenylamido species

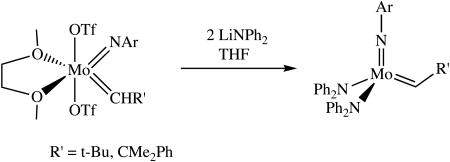

Addition of a cold suspension of two equivalents of LiNPh2 in THF or toluene to a stirred suspension of Mo(NAr)(CHR′)(OTf)2(dme) (R′ = t-Bu, CMe2Ph) in THF at -25 to -30 °C produced Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(NPh2)2 as a red solid, but the isolated yield was only 12%. The yield in the case of Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 was 35%. In both cases much manipulation was required to isolate a solid product. Alkylidene proton resonances for Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(NPh2)2 and Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 in benzene-d6 are found at 10.96 ppm and 11.18 ppm, respectively, and alkylidene carbon resonances were found at 294.8 and 292.6 ppm, respectively. The JCH values (117 and 119 Hz, respectively) are consistent with a syn orientation of the alkylidene.15,16 In the case of Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2, a second minor alkylidene proton resonance is observed at 11.78 ppm (∼5% of the total). We ascribe this resonance to the anti isomer, although we have not proven that to be the case through a determination of the value for JCH.

(1).

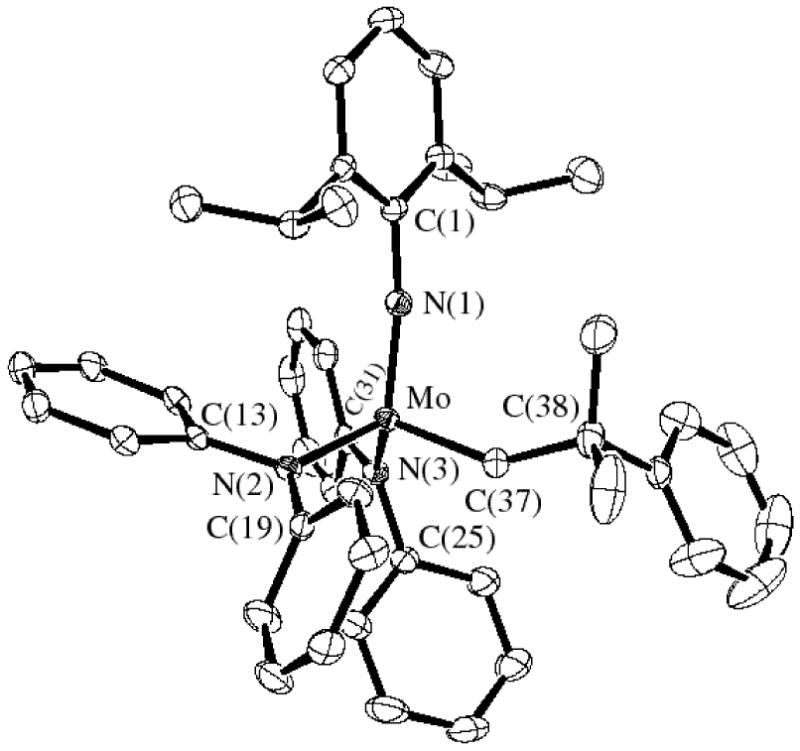

Single crystals of Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 suitable for X-ray crystallographic studies were obtained by layering a concentrated solution of the complex in dichloromethane with a minimum amount of pentane and storing the sample at -30 °C. In the solid state Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 has a pseudo tetrahedral geometry about the metal with the alkylidene ligand in the syn orientation, as expected (Figure 1). The Mo-C(37) double bond distance (1.877(3) Å) and the Mo-C(37)-C(38) bond angle (146.2(3)°) are typical of those found in a syn complex of this general type.15,16 The Mo-Namide bond lengths (2.009(3) Å and 2.007(3) Å) are similar to those found in a complex that contains a chelating diamido ligand, Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)[BINA(N-i-Pr)2] (Mo-Namide = 1.993 Å; [BINA(N-i-Pr)2]2- = N,N′-diisopropyl-2,2′-bisamido-1,1′-binaphthyl).12 The amido nitrogen atoms are essentially planar, as expected, and the two amido planes are virtually perpendicular to one another, as in Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)[BINA(N-i-Pr)2]. Therefore the lone pairs from both amido nitrogens can be donated to the metal and the total electron count at the metal can be said to be 18.

Figure 1.

Thermal ellipsoid drawing (50%) of Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2. (Hydrogen atoms are removed for clarity.)

The main problem with the route shown in equation 1 appears to be deprotonation of the alkylidene to yield a mixture of alkylidyne and other species, and diphenylamine. This type of side reaction has been documented in some cases,17 but not for reactions that involve amides. Since diphenylamine is extremely difficult to separate from the desired products, we believe that it is the presence of diphenylamine, rather than an inherently low yield, that limits how much pure product can be isolated, a statement that is supported by NMR analysis of crude reaction mixtures. In view of the reported synthesis of W(NAr)(CHEt)(NPh2)211 (vide supra) we therefore explored bishexafluoro-t-butoxides as starting materials.

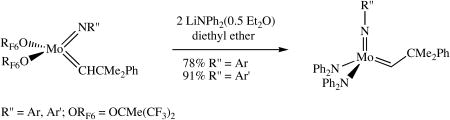

Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)[OCMe(CF3)2]2 can be obtained as yellow crystals in ∼85% yield in the reaction between Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(OTf)2(dme) and 2 equivalents of LiOCMe(CF3)2 in diethyl ether.18 (Hexafluoro-t-butoxide is a relatively weak base that does not deprotonate the alkylidene.) Treating a prechilled solution (-30 °C) of Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)[OCMe(CF3)2]2 in diethyl ether with two equivalents of LiNPh2(0.5 Et2O) afforded Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 as bright orange crystals in 78% isolated yield (equation 2). Mo(NAr′)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 can be prepared similarly as red-orange crystals in 91% yield starting from

(2).

Mo(NAr′)(CHCMe2Ph)[OCMe(CF3)2]2. The complexes prepared in this manner are identical to the samples obtained directly from the bistriflate species. In spite of the extra step (synthesis of hexafluoro-t-butoxides), this is the preferred method of producing pure product in high yield relatively quickly. It is known that the acidity of an alkylidene proton is reduced dramatically in alkoxide (even hexafluoro-t-butoxide) complexes compared to what it is in (e.g.) a triflate or a chloride complex,15 so deprotonation of the alkylidene is no longer problematic relative to substitution of the alkoxide.

Synthesis of Mo[N(R1)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2 complexes

Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)[N(R1)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2 (R1 = t-Bu, i-Pr) can be synthesized by treating a pre-chilled solution (-30 °C) of Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(OTf)2(dme) in diethyl ether or toluene with two equivalents of the corresponding LiN(R1)(3,5-C6H3Me2)(ether) salt. We believe that the yields again are compromised as a consequence of deprotonation of alkylidenes and consequent contamination of the product with the relatively high boiling parent amine. For example, Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)[N(t-Bu)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2 can be prepared and isolated in pure form as an orange-red crystalline solid in 34% yield. Proton and carbon NMR data (Table 3) are those expected for syn isomers. No alkylidene resonance for the anti isomer of Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)[N(t-Bu)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2 could be found at 22 °C. The 3,5-Me2C6H3 ring was found to be freely rotating on the NMR timescale. On the other hand, solid Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)[N(i-Pr)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2 could not be isolated free of HN(i-Pr)(3,5-C6H3Me2) in spite of repeated attempts at triturating the oily material with cold pentane or lyophilizing it in benzene. No improvement in the yield and purity of the desired product was observed when the different solvents (toluene, THF) and/or lower temperatures (-78 °C) were employed.

Table 3.

NMR data for bisamido complexes in benzene-d6 at 22 °C.

| Compound | δHα | δCα | JCH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)[N(t-Bu)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2 | 10.71 | 293.0 | 120 |

| Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)[N(i-Pr)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2 | 11.10 | 285.5 | 119 |

| Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(NPh2)2 | 10.96 | 294.8 | 117 |

| Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 | 11.18 | 292.6 | 119 |

| Mo(NAr′)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 | 11.08 | 292.5 | 122 |

Attempted syntheses of bisdimethylamido complexes from either Mo(NAr) or Mo(NAr′) triflates failed. Complex oily mixtures were obtained from which the pure products could not be isolated. Bright orange Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NMe2)2 could be obtained in a reaction between 2 equivalents of LiNMe2 and Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)[OCMe(CF3)2]2, but only in 16% yield (δHα = 10.69 ppm, δCα = 270.1 ppm). Since this synthesis is not viable in the long run this compound was not fully characterized.

Reactions of Mo(NR″)(CHR′)(NR2)2 complexes

None of the bisamido complexes reacted readily with simple olefins like ethylene and diallylether, or with benzaldehyde (e.g., several equivalents at room temperature over a period of 10 h), behavior which is similar to that found for [BINA(NR)2]2- complexes.12 Although steric factors are significant, the primary reason we believe to be an 18 electron count at the metal center (vide infra).

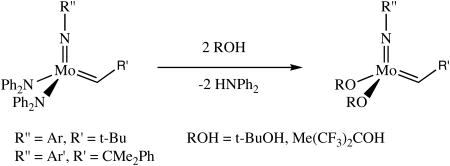

Both Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(NPh2)2 and Mo(NAr′)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 react readily with t-BuOH and (CF3)2MeCOH. Upon addition of the alcohol to 30 mM benzene solutions of the bisamide complexes, the bisalkoxide species, Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(OR)2 and Mo(NAr′)(CHCMe2Ph)(OR)2 (OR = O-t-Bu, OCMe(CF3)2), are obtained within 10 minutes

(3).

along with the expected amount of the free amine Ph2NH (equation 3). There was no indication that diphenylamine bound to the metal to give an adduct in either case, i.e., the chemical shift of the alkylidene proton is identical to that published for the base-free compounds. There is no evidence of any irreversible protonation of either the imido or the alkylidene ligand.

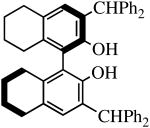

Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 and Mo(NAr′)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 (27 mM in benzene-d6) also react with one equivalent of H2[R-Benz2Bitet] to give the known Benz2Bitet complexes (equation 4). The two reactions proceed ∼90% to completion in 15 h at room temperature, with

(4).

the reaction involving Mo(NAr′)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 proceeding about twice as fast as that involving Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 and the conversion being slightly higher, presumably as a consequence of the lower steric demands of the 2,6-dimethylphenylimido ligand.

Reactions between Mo(NR″)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 (NR″ = NAr, NAr′) and the sterically demanding biphenol H2[Biphen] (Biphen2- = 3,3′-Di-t-butyl-5,5′,6,6′-tetramethyl-1,1′-Biphenyl-2,2′-diolate) were slow and incomplete and in some cases produced byproducts. For example, no reaction was observed when H2[Biphen] was added to a benzene-d6 (0.1 M) solution of Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 over a period of 2 days at room temperature. Heating the solution at 50 °C for 1 day shows 44% conversion to the desired Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)[Biphen] species but also four new alkylidene resonances appeared in the 11.40-11.80 ppm region (a total 20% of the mixture). The nature of the complex or complexes responsible for the new alkylidene resonances is (are) not known. When Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 was added to a benzene solution of H2[Biphen], the extra alkylidene peaks amount to less than 8% of the reaction mixture. However, complete conversion again was not observed. The reaction between H2[Biphen] and Mo(NAr′)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 was also slow, with only 64% conversion to Mo(NAr′)(CHCMe2Ph)[Biphen] observed in 7 days at 50 °C at concentrations of ∼0.1M.

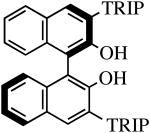

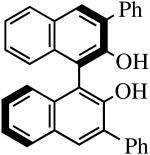

The binaphthols H2[R-TRIP2BINO],19 H2[R-Ph2BINO],20 H2[rac-Mes2BINO],20 and H2[R-TMS2BINO],21 react more readily with Mo(NR″)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2 (NR″ = NAr, NAr′) species than does H2[Biphen] (Table 4), but still not immediately. The reactions shown in Table 4 were carried out by adding the bisdiphenylamido complex to the diol in 2 drops of benzene-d6 (0.3 M). After heating the reaction mixtures for the stipulated time, more solvent was added and the % conversion and % product were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy versus an internal standard. Good to excellent conversions were found for virtually all the reactions, although the product mixture in some cases was found to contain small amounts (5-10%) of unidentified new alkylidenes along with the desired diolate product. The impurities amounted to ∼25% when the diol employed was H2[R-TMS2BINO], the dianion of which has not been studied extensively in the context of Mo(NR″)(CHCMe2Ph)(diolate*) chemistry.

Table 4.

Generation of binaphtholate catalysts in situ and conversions (ee) for asymmetric ring closing metathesis (equation 5).

| time (h), temp (°C) | % amide conv (% catalyst) | % substrate conv (% ee) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2[R-Benz2Bitet] |

|

R″ = Ar | 8.0, 50 | 100(81) | 77(94)a |

| R″ = Ar′ | 1.0, 70 | 100(100) | 99(97) | ||

| H2[R-TRIP2BINO] |

|

R″ = Ar | 48.0, 60 | 100(100) | 82(95) |

| R″ = Ar′ | 48.0, 60 | 100(100) | 99(96) | ||

| H2[R-Ph2BINO] |

|

R″ = Ar | 0.5, 50 | 100(100) | 90(68)b |

| R″ = Ar′ | 1.0, 70 | 100(100) | 95(87) | ||

| H2[rac-Mes2BINO] |

|

R″ = Ar | 14.0, 70 | 100(100) | 75c |

| R″ = Ar′ | 14.0, 70 | 91(86) | 93 | ||

| H2[R-TMS2BINO] |

|

R″ = Ar | 8.0, 50 | 82(56) | 92(72) |

| R″ = Ar′ | 36.0, 70 | 90(90) | 99(56) |

Reactions between alcohols and Mo(NAr)(CHR′)[N(R1)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2 complexes proceeded only very slowly (according to NMR studies) or not at all compared to similar reactions with Mo(NAr)(CHR′)(NPh2)2 species, probably largely for steric reasons. Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)[N(t-Bu)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2 reacted at room temperature with (CF3)2MeCOH in benzene-d6 (28 mM) to give the bisalkoxide within 10 minutes. However, the analogous reaction proceeded very slowly (∼ 12-15 h) when t-BuOH was employed. Reactions involving Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)[N(i-Pr)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2 with both (CF3)2MeCOH and t-BuOH were complete in 10 minutes under conditions noted above. All Mo(NAr)(CHR′)[N(R1)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2 complexes showed virtually a complete lack of reactivity toward the enantiomerically pure diols shown in Table 4.

Conversions and enantioselectivities in a simple asymmetric ring-closing metathesis reaction (equation 5) are also listed in Table 4. Conversions of the substrate range from 56% to 97% with the highest ee being 97%. For the first22 and third20 entries the ring-closing

(5).

also has been carried out with isolated catalyst. The results for the in situ generated catalyst and for the isolated catalyst are comparable. In particular the %ee's are essentially the same. The in situ catalyst appears to be somewhat slower (first and fourth entries) versus the isolated catalysts, although detailed studies have not been carried out. It should be noted that the first three in situ catalysts that contain a 2,6-dimethylphenyl imido ligand are slightly superior in terms of %ee than catalysts that contain the 2,6-diisopropylphenyl imido ligand; the 2,6-diisopropylphenyl imido derivatives were the only isolated catalysts that were examined.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that bisamido complexes can be prepared starting from bistriflate complexes, although yields are low and the products are difficult to isolate. In some cases yields can be improved through the use of Mo(NR″)(CHR′)[OCMe(CF3)2]2 complexes as starting materials. Reactions in which bisdiphenylamido complexes are prepared from hexafluoro-t-butoxide species are high yielding and clean, and for this reason are preferred over reactions that start with bistriflates. On the basis of preliminary studies, NAr and NAr′ complexes containing NPh2 ligands react with a variety of enantiomerically pure binaphthols to give the desired chiral catalysts in situ, the exception being H2[Biphen], which is the most sterically demanding. In these reactions diphenylamine apparently does not bind to the metal, nor does it hinder asymmetric reactions (to the degree that we have explored for one substrate) in terms of either substrate conversion or %ee. Therefore this approach to in situ catalyst generation and use is an attractive one, especially if a nitrogen-based anionic ligand can be found that produces a catalyst precursor in high yield and if that catalyst precursor were to react with even the most sterically demanding biphenols or binaphthols. In this manner we hope to be able to reduce the problem of catalyst evaluation to the synthesis and storage of a few Mo(NR″)(CHR′)X2 precursors.

Experimental Section

General

All operations were performed under a nitrogen atmosphere in the absence of oxygen and moisture in a Vacuum Atmospheres glovebox or using standard Schlenk procedures. All glassware, including NMR tubes, were flame- and/or oven-dried prior to use. Ether, pentane, toluene, and benzene were degassed with dinitrogen and passed through activated alumina columns. Dimethoxyethane was distilled from a dark purple solution of sodium benzophenone ketyl and degassed three time by freeze-pump-thaw techniques. Dichloromethane was distilled from CaH2 under N2. All dried and deoxygenated solvents were stored over 4 Å molecular sieves in a nitrogen-filled glovebox. 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra were acquired at room temperature (unless otherwise noted) using Varian Mercury (1H 300 MHz, 13C 75 MHz, 19F 282 MHz) or Varian Inova (1H 500 MHz, 13C 125 MHz) spectrometers and referenced to the residual protio solvent resonances or external C6F6 (-163.0 ppm). Elemental Analyses were performed by H. Kolbe Mikroanalytisches Laboratorium, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany. Mo(NR″)(CHR′)(OTf)2(dme) complexes, LiN(i-Pr)(3,5-C6H3Me2), and LiN(t-Bu)(3,5-C6H3Me2) were prepared as described in the literature.18,23,24,25 LiNPh2 was prepared by reacting HNPh2 with n-BuLi (1.6 M in hexane) in toluene. LiNPh2(0.5 ether) was obtained by crystallizing LiNPh2 from diethyl ether. LiNMe2 was prepared by reacting HNMe2 with n-BuLi (1.6 M in hexane) in toluene. All other chemicals were procured from commercial sources and used as received.

Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(NPh2)2

A solution of Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(OTf)2(dme) (6.00 g, 8.22 mmol) in 80 mL THF at -30 °C was treated with a pre-chilled solution of LiNPh2 (2.88 g, 16.44 mmol) in 20 mL THF. The color changed from yellow to red immediately. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1h and allowed to warm to room temperature. The volatiles were removed in vacuo and the residue was extracted with pentane. The extracts were filtered through Celite and the solvents again were removed in vacuo to give an oil that was triturated with minimal pentane. Filtration yielded an orange-red powder in 12 % yield (669 mg). The remaining pentane-soluble red oil was found to consist mostly of the desired complex according to proton NMR: 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 10.96 (s, 1, CHCMe3, JCH = 117 Hz), 7.12 -6.83 (overlapping peaks, 23, ArH, NPh2), 3.90 (sept, 2, CHMe2), 1.81 (d, 12, CHMe2), 0.98 (s, 9, CHCMe3); 13C NMR (C6D6) δ 294.8. Anal. Calcd for C41H47MoN3: C, 72.66; H, 6.99; N, 6.20. Found: C, 72.52; H, 7.08; N, 6.11.

Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2

Method A

Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(OTf)2(dme) (500 mg, 0.63 mmol) was dissolve in 8mL of THF and the solution was cooled to -30 °C. A pre-chilled solution of LiNPh2 (221 mg, 1.26 mmol) in 2mL THF was added to the above solution in a drop-wise fashion to immediately afford a red solution. After 1 hour the volatiles were removed in vacuo to give a red foam which was extracted with pentane. The extract was filtered through Celite and the filtrate was concentrated to dryness to yield a red oil. The oil was triturated with cold pentane several times to give 163 mg of an orange-red powder (35% yield).

Method B

A yellow solution of Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)[OCMe(CF3)2]2 (505 mg, 0.66 mmol) in 50 mL ether was cooled to -30 °C. Gradual addition of 2 equivalents of LiNPh2(Et2O)0.5 (280 mg, 1.32 mmol) to the above reaction resulted in a change in color from yellow to orange to red as the reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h. The solvents were partially removed and the concentrated solution layered with 5 mL pentane; bright orange product crystallized out. The orange crystals were washed with 5 mL of cold pentane (-30 °C) to afford the desired complex in 78% yield (380 mg) in two crops: 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 11.78 (s, 0.04, anti CHCMe2Ph), 11.18 (s, 1, syn CHCMe2Ph, JCH = 119 Hz), 7.10-6.79 (overlapping peaks, 28, ArH, NPh2), 3.86 (sept, 2, CHMe2), 1.45 (s, 6, CHCMe2Ph), 1.61 (d, 12, CHMe2); 13C NMR (C6D6) δ 292.6, 155.5, 154.1, 148.5, 146.3, 129.9, 128.9, 127.8, 126.5, 126.4, 124.6, 123.9, 123.6, 55.7, 31.0, 28.6, 24.7. Anal. Calcd for C46H49MoN3: C, 74.68; H, 6.68; N, 5.68. Found: C, 74.57; H, 6.62; N, 5.69.

Mo(NAr′)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2

Mo(NAr′)(CHCMe2Ph)[OCMe(CF3)2]2 (539 mg, 0.76 mmol) in 55 mL ether was chilled to -30 °C. Gradual addition of 2 equivalents of LiNPh2(Et2O)0.5 (322 mg, 1.52 mmol) to the above reaction resulted in a change in color from yellow to orange to red-orange as the reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h and the solvents were partially removed in vacuo. The concentrated solution was layered with 5 mL pentane. Bright red-orange solid crystallized out and was washed with 3 mL of cold (-30 °C) pentane; yield 475 mg (91%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 11.08 (s, 1, CHCMe2Ph, JCH = 122 Hz), 7.10-6.81 (overlapping peaks, 28, ArH, NPh2), 2.33 (s, 6, CHCMe2Ph), 1.37 (s, 6, Ar′Me2); 13C NMR (C6D6) δ 292.5, 157.2, 155.2, 148.4, 135.4, 129.9, 128.8, 126.8, 126.5, 126.4, 124.5, 123.6, 55.3, 30.5, 19.6. Anal. Calcd for C42H41MoN3: C, 73.78; H, 6.04; N, 6.15. Found: C, 73.59; H, 6.12; N, 6.02.

Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)[N(t-Bu)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2

LiN(t-Bu)(3,5-C6H3Me2)(ether) (330 mg, 1.28 mmol) was added to a suspension of Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(OTf)2(dme) (468 mg, 0.64 mmol) in 30 mL ether at -30 °C. The red solution was stirred at ambient temperature for 1.5 h. The volatiles were removed in vacuo and the residue was extracted into pentane. The pentane was removed in vacuo to give a red oil. Extensive trituration with cold pentane gave a waxy red solid. The waxy solid was dissolved in a minimum amount of pentane and the solution was stored at -30 °C overnight to give 152 mg (34%) of the product as orange-red crystals: 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 10.71 (s, 1, CHCMe3, JCH = 120 Hz), 7.17 (br s, 2, ArH), 7.09 (br s, 5, ArH), 6.68 (br s, 2, ArH), 4.58 (sept, 2, CHMe2), 2.22 (s, 12, C6H3Me2), 1.38 (d, 12, CHMe2), 1.34 (s, 18, NCMe3), 0.98 (s, 9, CHCMe3); 13C NMR (C6D6) δ 293.0, 157.2, 153.9, 144.9, 137.9, 129.7, 126.6, 126.2, 124.3, 59.5, 48.7, 32.3, 31.5, 27.6, 24.6, 21.7. Anal. Calcd for C41H63N3Mo: C, 70.97; H, 9.15; N, 6.06. Found: C, 71.06; H, 9.06; N, 5.97.

Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)[N(i-Pr)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2

An ether solution of LiN(i-Pr)(3,5-C6H3Me2)(ether) (343 mg, 1.41 mmol) was added to a suspension of Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)(OTf)2(dme) (6.00 g, 8.22 mmol) in 40 mL of ether at -30 °C. The deep red reaction mixture at room temperature for 1 h and all solvents were removed under reduced pressure. The residue was extracted with pentane and the extract was filtered through Celite to yield a red liquid which was concentrated in vacuo to yield a red oil that contained 70% Mo(NAr)(CH-t-Bu)[N(i-Pr)(3,5-C6H3Me2)]2 and 30% HN(i-Pr)(3,5-C6H3Me2) that could not be removed on a high vacuum line, or by heating the oil under reduced pressure: 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 11.10 (s, 1, CHCMe3, JCH = 119 Hz), 7.07 (br s, 3, ArH), 6.85 (br s, 4, ArH), 6.56 (br s, 2, ArH), 4.25 (sept, 2, CHMe2), 4.01 (sept, 2, CHMe2), 2.14 (s, 12, C6H3Me2), 1.26 (d, 12, CHMe2), 1.23 (d, 12, CHMe2), 1.19 (s, 9, CHCMe3); 13C NMR (C6D6): δ 285.2, 154.9, 145.0, 138.5, 126.4, 125.0, 123.7, 123.2, 58.6, 48.4, 32.2, 28.2, 25.4, 25.0, 24.9, 21.9.

Representative method for generating Mo(NR″)(CHCMe2Ph)(diolate*) and using it as a catalyst for ring-closing

The bisamido precursor (10-20 mg) was added to a solution of the enantiomerically pure diol in 0.5 mL drops of benzene-d6 in a J-Young tube. The reaction mixture was heated at 60 °C till the starting materials were consumed. The progress of the reaction was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy versus an internal standard.

To the Mo(NR″)(CHCMe2Ph)(diolate*) species generated as described above, 20 equivalents of the substrate was added. The conversion was followed by 1H NMR spectroscopy and the enantiomeric excess was determined with a GC equipped with a Chiraldex column.

Supplementary Material

Crystal data and structure refinement, atomic coordinates and equivalent isotropic displacement parameters, bond lengths and angles, anisotropic displacement parameters, hydrogen coordinates, and isotropic displacement parameters for Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2. Supporting Information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. Data for the structure (04220) are also available to the public at http://www.reciprocalnet.org/.

Table 1.

Crystal data and structure refinement for Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2.

| Empirical formula | C46H49N3Mo | |

| Formula weight | 739.82 | |

| Temperature | 100(2) K | |

| Wavelength | 0.71073 Å | |

| Crystal system | Triclinic | |

| Space group | P1̄ | |

| Unit cell dimensions | a = 9.279(3) Å | α = 79.848(6) ° |

| b = 20.158(7) Å | β = 89.997(6) ° | |

| c = 20.739(8) Å | γ = 83.507(6) ° | |

| Volume | 3793(2) Å 3 | |

| Z | 4 | |

| Density (calculated) | 1.296 Mg/m3 | |

| Absorption coefficient | 0.382 mm-1 | |

| F(000) | 1552 | |

| Crystal size | 0.20 × 0.15 × 0.05 mm3 | |

| Theta range for data collection | 1.00 to 28.49° | |

| Index ranges | -12 ≤ h ≤12, -26 ≤ k ≤27, 0 ≤ l ≤27 | |

| Reflections collected | 23610 | |

| Independent reflections | 23612 [non-merohedral twin] | |

| Completeness to theta = 28.49° | 97.2 % | |

| Absorption correction | Semi-empirical from equivalents | |

| Max. and min. transmission | 0.9812 and 0.9276 | |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 | |

| Data / restraints / parameters | 23612 / 0 / 914 | |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.020 | |

| Final R indices [I>2sigma(I)] | R1 = 0.0486, wR2 = 0.1032 | |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0726, wR2 = 0.1119 | |

| Largest diff. peak and hole | 0.946 and -0.517 e. Å-3 |

Table 2.

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°] for Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2.

| Mo-N(1) | 1.739(3) | Mo-C(37) | 1.877(3) |

| Mo-N(3) | 2.007(3) | Mo-N(2) | 2.009(3) |

| N(1)-C(1) | 1.406(4) | N(1)-Mo-C(37) | 103.98(13) |

| N(1)-Mo-N(2) | 114.03(11) | N(1)-Mo-N(3) | 116.34(11) |

| N(2)-Mo-N(3) | 110.32(10) | N(2)-Mo-C(37) | 104.07(12) |

| N(3)-Mo-C(37) | 106.86(12) | Mo-C(37)-C(38) | 146.2(3) |

| Mo-N(1)-C(1) | 169.0(2) | C(13)-N(2)-C(19) | 115.2(2) |

| C(13)-N(2)-Mo | 118.61(19) | C(19)-N(2)-Mo | 125.61(19) |

| C(31)-N(3)-C(25) | 117.6(3) | C(31)-N(3)-Mo | 132.3(2) |

| C(25)-N(3)-Mo | 110.1(2) |

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the NIH (GM-59426 to A.H.H. and R.R.S.) and the National Science Foundation (CHE-0138495 to R.R.S.). A.S. thanks Zachary Tonzetich for the gift of LiNMe2 and Adam Hock for the gift of LiN(t-Bu)(3,5-Me2C6H3) etherate.

References

- 1.Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:4592. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Copéret C, Chabanas M, Saint-Arroman RP, Basset JM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:156. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teng X, Cefalo DR, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10779. doi: 10.1021/ja020671s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinha A, Lopez LPH, Schrock RR, Hock AS, Müller P. Organometallics. 2006;25:1412. doi: 10.1021/om060430j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanc F, Baudouin A, Copéret C, Thivolle-Cazat J, Basset JM, Lesage A, Emsley L, R SR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:1216. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gade LH, Mountford P. Coord Chem Rev. 2001;216-217:65. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai YC, Diaconescu PL, Cummins CC. Organometallics. 2000;19:5260. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherry JPF, Stephens FH, Johnson MJA, Diaconescu PL, Cummins CC. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:6860. doi: 10.1021/ic015592g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephens FH, Figueroa JS, Diaconescu PL, Cummins CC. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9264. doi: 10.1021/ja0354317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Zhang W, Kraft S, Moore JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:329. doi: 10.1021/ja0379868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Weissman H, Plunkett KN, Moore JS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:585. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhang W, Kraft S, Moore JS. Chem Commun. 2003:832. doi: 10.1039/b212405j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schrock RR, DePue RT, Feldman J, Yap KB, Yang DC, Davis WM, Park LY, DiMare M, Schofield M, Anhaus J, Walborsky E, Evitt E, Krüger C, Betz P. Organometallics. 1990;9:2262. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamieson JY, Schrock RR, Davis WM, Bonitatebus PJ, Zhu SS, Hoveyda AH. Organometallics. 2000;19:92. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortiz CG, Abboud KA, Boncella JM. Organometallics. 1999;18:4253. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) VanderLende DD, Abboud KA, Boncella JM. Organometallics. 1994;13:3378. [Google Scholar]; (b) Vaughan WM, Abboud KA, Boncella JM. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:11015. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang SYS, VanderLende DD, Abboud KA, Boncella JM. Organometallics. 1998;17:2628. [Google Scholar]; (d) Vaughan WM, Abboud KA, Boncella JM. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:11015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman J, Schrock RR. Prog Inorg Chem. 1991;39:1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schrock RR. Chem Rev. 2002;102:145. doi: 10.1021/cr0103726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schrock RR, Jamieson JY, Araujo JP, Bonitatebus PJ, Jr, Sinha A, Lopez LPH. J Organomet Chem. 2003;684:56. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schrock RR, Murdzek JS, Bazan GC, Robbins J, DiMare M, O'Regan M. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:3875. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu SS, Cefalo DR, La DS, Jamieson JY, Davis WM, Hoveyda AH, Schrock RR. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:8251. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsang WCP, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Organometallics. 2001;20:5658. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Totland KM, Boyd TJ, Lavoie GG, Davis WM, Schrock RR. Macromolecules. 1996;29:6114. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrock RR, Jamieson JY, Dolman SJ, Miller SA, Bonitatebus PJ, Jr, Hoveyda AH. Organometallics. 2002;21:409. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oskam JH, Fox HH, Yap KB, McConville DH, O'Dell R, Lichtenstein BJ, Schrock RR. J Organomet Chem. 1993;459:185. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai YC, Stephens FH, Meyer K, Mendiratta A, Gheorghiu MD, Cummins CC. Organometallics. 2003;22:2902. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Micovic IV, Ivanovic MD, Piatak DM, Bojic VJ. Synthesis. 1991:1043. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Crystal data and structure refinement, atomic coordinates and equivalent isotropic displacement parameters, bond lengths and angles, anisotropic displacement parameters, hydrogen coordinates, and isotropic displacement parameters for Mo(NAr)(CHCMe2Ph)(NPh2)2. Supporting Information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. Data for the structure (04220) are also available to the public at http://www.reciprocalnet.org/.