Abstract

Inward-rectifier potassium (Kir) channels differ from the canonical K+ channel structure in that they possess a long extended pore (∼85 Å) for ion conduction that reaches deeply into the cytoplasm. This unique structural feature is presumably involved in regulating functional properties specific to Kir channels, such as conductance, rectification block, and ligand-dependent gating. To elucidate the underpinnings of these functional roles, we examine the electrostatics of an ion along this extended pore. Homology models are constructed based on the open-state model of KirBac1.1 for four mammalian Kir channels: Kir1.1/ROMK, Kir2.1/IRK, Kir3.1/GIRK, and Kir6.2/KATP. By solving the Poisson-Boltzmann equation, the electrostatic free energy of a K+ ion is determined along each pore, revealing that mammalian Kir channels provide a favorable environment for cations and suggesting the existence of high-density regions in the cytoplasmic domain and cavity. The contribution from the reaction field (the self-energy arising from the dielectric polarization induced by the ion's charge in the complex geometry of the pore) is unfavorable inside the long pore. However, this is well compensated by the electrostatic interaction with the static field arising from the protein charges and shielded by the dielectric surrounding. Decomposition of the static field provides a list of residues that display remarkable correspondence with existing mutagenesis data identifying amino acids that affect conduction and rectification. Many of these residues demonstrate interactions with the ion over long distances, up to 40 Å, suggesting that mutations potentially affect ion or blocker energetics over the entire pore. These results provide a foundation for understanding ion interactions in Kir channels and extend to the study of ion permeation, block, and gating in long, cation-specific pores.

INTRODUCTION

The central issue underlying biological ion permeation is how a protein facilitates the passage of a charged ion across the high-energy barrier of the lipid bilayer. A variety of solutions to this problem are exemplified by the different types of ion channels observed in nature (Hille, 2001; Jackson, 2006). Bacterial porins and mechanosensitive channels use a straightforward approach by construction of a wide water-filled pore enabling a nonselective conductance with nearly ohmic behavior. At the other end of complexity is the potassium channel, which contains a series of binding sites forming a “selectivity filter” that spans halfway across the membrane enabling a K+ selective conductance with high flux due to multi-ion coupling between these sites. The other half of the transmembrane channel structure forms an aqueous cavity, which stabilizes an ion via long-range electrostatic interactions from the protein (Roux and MacKinnon, 1999). This combination of features provides the principal template for ion conduction that is conserved among all K+ selective channels. The diversity between different K+ channel families occurs in part through structural amendments to this basic template. A prime example of this is found in the family of inward-rectifier potassium (Kir) channels, so named for their characteristic inhibition of outward current due to voltage-dependent block by cytoplasmic polyvalent cations (Nichols and Lopatin, 1997; Lu, 2004). In 2003, Kuo et al., determined the first full-length structure of a bacterial Kir homologue KirBac1.1, revealing that Kir channels contain a transmembrane domain very similar to the ∼30-Å KcsA channel, as well as a long cytoplasmic domain that extends the ion conduction pore to >∼85 Å (Kuo et al., 2003).

Within the Kir family, channels show strong similarities in both sequence and structure, yet a remarkable diversity in function (Bichet et al., 2003). For instance, there are strong rectifiers such as Kir2.1/IRK1 in muscle and Kir3.1/GIRK in neurons that inhibit nearly all of the outward current except for conductance just positive to the reversal potential. This is important in excitable cells as it shuts off inhibitory K+ currents during the action potential yet assists in maintaining the resting membrane potential during the repolarization phase. Other Kir channels tend to be weakly rectifying but highly regulated, for example Kir1.1/ROMK in the kidneys and Kir6.2/KATP in pancreatic β cells. Factors that modulate Kir gating include pH in Kir1.1/ROMK, G proteins in Kir3.1/GIRK, ATP in Kir6.2/KATP, and PIP2 in all Kir channels. The breadth of differences presents the question of how these channels create functional diversity on a structurally similar template.

Experimental studies have shed light on some of the molecular components involved. The availability of a diverse set of proteins within the same family allowed for the construction of chimeras to exchange functional effects, resulting in the identification of key residues involved in rectification, conductance, and gating. Two negatively charged residues in Kir2.1/IRK, D172 in the cavity and E224 in the cytoplasmic domain, were found to be important for strong rectification and not present in Kir1.1/ROMK. Introduction of the cavity aspartate at the corresponding position in Kir1.1/ROMK (N171D) confers rectification behavior (Lu and MacKinnon, 1994; Stanfield et al., 1994; Wible et al., 1994; Taglialatela et al., 1995; Yang et al., 1995). The role of the C-terminal negative charge is more complex; introducing the glutamate in Kir1.1/ROMK (G223E) did not increase rectification, whereas substitution of the entire C terminus of Kir2.1/IRK did produce strong inward rectification (Taglialatela et al., 1994, 1995). Thus, other residues, and perhaps the entire structure of the cytoplasmic domain, must be involved. Similar studies have revealed residues selective in regulating conductance and not rectification, for instance R260 in Kir2.1/IRK that reduces the conductance when mutated at the corresponding position, N259R in Kir1.1/ROMK (Zhang et al., 2004). With respect to gating, many residues have been shown to be involved with the binding and activation by PIP2, with as many as 12 positively charged residues per subunit in Kir2.1/IRK (Lopes et al., 2002). In addition, pH gating of Kir1.1/ROMK has been attributed to a functional triad of three positively charged residues at several positions within the channel, R41/K80/R311 (Schulte et al., 1999). This represents a small fraction of the mutagenesis information available, yet it demonstrates the underlying trend that charged residues play key roles in modulating Kir channel behavior. What is yet to be understood is how these charged residues affect specific properties of different ions inside the long, extended pore to bring about such a wide range of effects in conductance, rectification, and even gating.

This study investigates the hypothesis that this variation in Kir channel behavior occurs primarily through electrostatic modulation along the extended pore. Based on the open-channel model of KirBac1.1 (Kuo et al., 2005; Domene et al., 2005), we construct homology models of four mammalian Kir channels in the open state: Kir1.1/ROMK1, Kir2.1/IRK1, Kir3.1/GIRK1, and Kir6.2/KATP. We then calculate the electrostatic free energy of an ion along the central pore by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation to determine the robust electrostatic features characteristic of each Kir channel. Further decomposition of the ion interaction energies allows us to attribute these features to architectural components or specific sequence variations within each channel. The strong correlation of electrostatics results with past experimental data demonstrates that this characterization of the simpler single-ion electrostatics is a fundamental first step in understanding the more complicated mechanisms of conductance, rectification, and gating.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Homology Modeling of Mammalian Kir Channels

Sequence alignments of Kir1.1/ROMK1, Kir2.1/IRK1, Kir3.1/GIRK1, and Kir6.2/KATP1 with KirBac1.1 were determined using clustalw (Chenna et al., 2003) and manually adjusted using the sequence alignment editor jalview (Clamp et al., 2004) to limit insertions and deletions to the loop regions. Using different strategies, three alignments were constructed for each channel: (1) pairwise alignment with KirBac1.1, (2) multiple alignment of all four Kirs with KirBac1.1, and (3) multiple alignment in (2) with a shift in the insertions. The template structure was the KirBac1.1 open model based on the 2D electron crystallography data of a putative open state of KirBac3.1 (Kuo et al., 2005; Domene et al., 2005). Building and refinement of the models were performed using the molecular modeling program CHARMM (MacKerell et al., 1998). Backbone coordinates and similar side chain atoms were copied exactly from the template structure for all residues not in the inserted and deleted regions. To create the insertions, Cα atoms were built every 2.5 Å forming a hairpin loop in between flanking residues. The deletions consisted of removing residues from the template and then translating the coordinates of the flanking residues to bridge the gap. Any atoms still missing from the target structure were built from the internal coordinate table. Side chains of dissimilar residues were optimized using the side chain rotamer library SCWRL (Canutescu et al., 2003). The minimization procedure began with relaxation of the inserted and deleted regions with the rest of the protein fixed. The constraints were gradually removed until the entire protein was free except for constraints on the selectivity filter backbone atoms and ions in S1 and S3 (S1z = 15 Å, S3z = 9 Å, and cavityz = 0). These structures formed the first set of homology models used in the calculations. The second set imposed two experimental distance restraints: (1) a glutamate-arginine salt bridge behind the selectivity filter corresponding to E138/R148 in Kir2.1/IRK (Yang et al., 1997) and (2) a disulfide bond between two cysteine residues in the extracellular loops of each subunit corresponding to C122/C154 in Kir2.1/IRK (Leyland et al., 1999; Cho et al., 2000). To equilibrate the side chains in appropriate solvent environments, short langevin dynamics simulations (100 ps) were performed on both sets of structures using a Generalized Born implicit-solvent model (Im et al., 2003), with the solvent represented as a dielectric of 80 and membrane as a dielectric slab of 2. Except for the atoms in the loop regions, a 5 kBT restraint was placed on all Cα atoms preventing any large structural changes. Electrostatics calculations are particularly sensitive to the charge distribution in regions in the low dielectric, and the channels contain an aspartate/asparagine inside the transmembrane cavity that is built predominantly in one rotameric state. To introduce some variability of the charge distribution at this position, additional sets of structures were constructed based on the first two sets in which the χ1 dihedral angle of the residue corresponding to D172 in Kir2.1/IRK was rotated 180° to change its orientation relative to the pore. In summary, four different sets of models were constructed for each of the sequence alignments resulting in a total of 12 models for each Kir channel. Fig. 1 A shows an example of each of the four mammalian Kir channels overlapped onto the KirBac1.1 template.

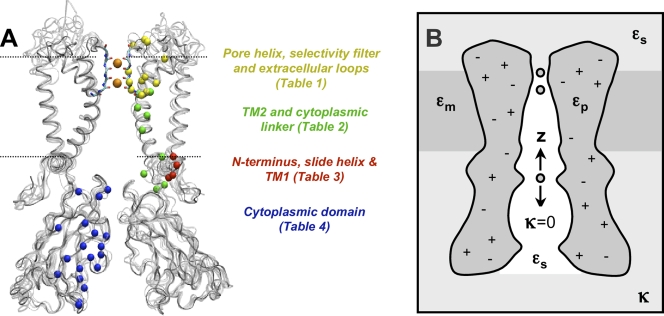

Figure 1.

Homology models of Kir channels and PB system definition. (A) Structures of KirBac1.1, Kir1.1/ROMK, Kir2.1/IRK, Kir3.1/GIRK, and Kir6.2/KATP are overlaid in gray for comparison. Two subunits are removed for clear view of the open pore. The backbone of the selectivity filter is shown explicitly with two potassium ions in the pore. The membrane is centered at the cavity and is designated by the dashed lines. The positions of electrostatically significant residues are depicted by the colored spheres according to structural domains, which are listed in the corresponding tables: (I) pore helix, selectivity filter, and extracellular loops (yellow), (II) TM2 (green), (III) cytoplasmic membrane interface (blue), and (IV) cytoplasmic domain (red). (B) System definition for PB calculations. The channel pore is defined along the z axis with the membrane between −12.5 Å < z < 12.5 Å and dielectric constant εm. The protein dielectric is defined as εp and the solvent as εs. Debye-Hückel factor κ is 0 inside the pore.

PB Calculations

The PB equation:

|

(1) |

describes the electrostatic potential φ(r) created by a distribution of charges, ρ(r), and Debye-Hückel ionic screening, κ2(r), in a dielectric continuum, ε(r). For complex irregular geometries, a numerical solution of the potential field can be determined by mapping the system onto a 3D grid and using a finite-difference algorithm to obtain the solution to the differential equation. Details about these methods can be found in numerous papers (Warwicker and Watson, 1982; Honig and Nicholls, 1995; Im et al., 1998). In brief, the PB equation is formally rewritten as a Green's function,

|

(2) |

where the matrix M−1 represents the finite-difference form of the differential operator of Eq. 1 at every grid point, and φ is the numerical solution obtained iteratively across the entire system. For a system of n charges (q1,…,qn) the electrostatic potential energy for the entire system is:

|

(3) |

such that Mijqj is the electrostatic potential created by charge qj at the position of the charge qi, and the 1/2 term in front accounts for duplicate counting of the charges.

With these formal definitions, the electrostatic free energy of interaction corresponding to the energy of transferring an ion from the bulk into the channel pore can be determined by finding the difference in electrostatic energy between three separate systems:

|

(4) |

where IC represents the ion–channel complex, C represents the channel alone, and I represents the ion alone in bulk. This electrostatic interaction free energy can be decomposed into a more physically meaningful form if we expand each term into its matrix components. For a system of one free ion in the channel, q1 and the channel charges (q2,…,qn):

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

Rewriting this as a function of the free ion q1=Qion:

|

(7) |

The first energetic term, ΔGRF-PROT = 1/2AQion2, is the energy that an ion experiences due to the reaction field created by the protein dielectric in response to the ion charge. The second term, ΔGSF = BQion, is the energy of the ion in the static field established by the protein charges. Finally, the last term, ΔGRF-ION = C, reflects the energy due to the reaction field created by the ion dielectric in response to the protein charges. The complete energetic balance of an ion in the channel depends on the sum of these three terms, and follows a quadratic dependency on the ion charge (Roux and MacKinnon, 1999; Roux et al., 2000; Faraldo-Gomez and Roux, 2004; Jogini and Roux, 2005).

All of the electrostatics calculations presented here were performed using the PBEQ module in CHARMM (version C32a2). The system was set up as shown in Fig. 1 B, such that the pore axis was aligned lengthwise along the z axis and the selectivity filter binding sites positioned at S1z = 15 Å and S3z = 9 Å, which centers the cavity at z = 0 Å. The membrane was represented as a low-dielectric slab (εm = 2) of 25-Å thickness and centered at z = 0 Å. For all calculations, the protein dielectric was set to εp = 2 and the solvent was set to εs = 80. Calculations were also performed with εp = 10, changing magnitudes but not the qualitative features of the energy and therefore are reported in the online supplemental material (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200810068/DC1). The aqueous pore was defined with a dielectric εs = 80 and no Debye-Hückel ionic screening, i.e., κ = 0. Outside of the pore, an ionic concentration corresponding to 150 mM KCl was defined to consider long-range screening in the bulk solution. Dielectric boundaries were defined by a reentrant surface with a water probe of 1.4 Å. The grid was defined with ∼241 × 241 × 439 grid points and cell size 1.0 Å, focused to 0.5 Å. All calculations were performed with K+ ions in the S1/S3 sites of the selectivity filter. Note that we limit our calculations to regions that are wide enough to properly define the dielectric boundaries, i.e from the cytoplasmic domain to the cavity. The use of the PB equation is not appropriate in confined regions such as the selectivity filter (Allen et al., 2004).

Online Supplemental Material

Variables that have the ability to affect the electrostatic calculations are investigated in the online supplemental material. First, the effect of the protein dielectric constant is considered by calculating the total electrostatic free energy for K+ along the pore of Kir1.1/ROMK, with εP = 2 and εP = 10 for each of the 12 models (Fig. S1). The decomposition of the static field by residue for each z position is also calculated. In general, the magnitudes are slightly less with the increased protein dielectric; however, the qualitative features of the profiles and static field decay are not strongly affected. Another variable that is considered is the ion configuration within the selectivity filter (Fig. S2). The interaction energies of K+ and SPM4+ are calculated along the Kir2.1/IRK pore for three configurations: S1 (z = 15 Å) and S3 (z = 9 Å), S2 (z = 12 Å) and S4 (z = 6 Å), or no ions in the filter. As expected, ions in S2/S4 provide stronger repulsion for another ion along the pore. In the case of spermine (SPM4+) interaction, even when ions are completely removed from the filter, the K+ energy is still more favorable than SPM4+. Therefore, our results are not strongly dependent on the configuration of ions inside the filter, and so we limit our calculations to structures with ions in S1/S3.

RESULTS

Ion permeation is a kinetic process that is largely controlled by the relative thermodynamic free energies of ions in bulk solution and inside a channel pore. Therefore, a study of the electrostatics involved in ion permeation in any ion channel must consider the full electrostatic free energy. As outlined in Materials and methods, this energy includes the interaction of an ion with the protein charges shielded by the surrounding dielectric (static field) and the self-energy that arises from the polarization of the dielectric induced by nearby charges (reaction fields). At a simpler level, electrostatics analysis may consider only the static field and neglect the contribution of the reaction fields. Although this is suitable for analyzing structural features of the charge distribution, it is missing key information that relates electrostatics to the behavior of ion permeation. In the following analysis, we calculate the full electrostatic free energies for a single ion along the channel pore and proceed to decompose the static and reaction field contributions to understand the electrostatic features that regulate ion permeation in Kir channels.

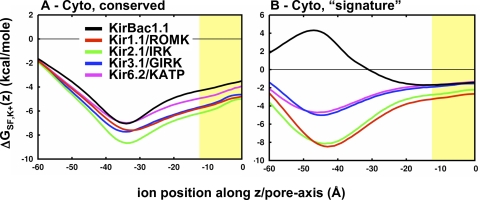

Electrostatic Free Energy of K+ along the Kir Channel Pore

The electrostatic free energy of transferring a K+ ion from the bulk and into the center of the pore is calculated for each of the different Kir channels and is shown in Fig. 2. These profiles are averaged over 12 different models of each channel, and the error bars represent the standard deviation of the calculations. These profiles depict the general electrostatic architecture along the inward-rectifier pore and how the different channels modulate the overall energetic landscape. From this, three electrostatic domains are observed: (1) the cytoplasmic domain, (2) the cytoplasmic–transmembrane linker, and (3) the channel cavity at the center of the membrane.

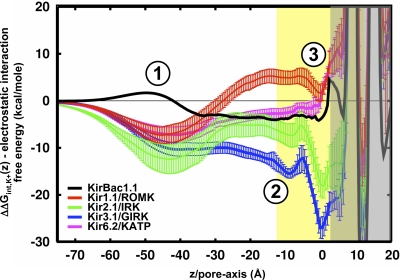

Figure 2.

Electrostatic interaction free energy of K+ along the Kir channel pore. Average ΔΔGint,K+(z) profiles for KirBac1.1 (black; n = 1), Kir1.1/ROMK (red; n = 12), Kir2.1/IRK (green; n = 12), Kir3.1/GIRK (blue; n = 12), and Kir6.2/KATP (magenta; n = 12). The error bars represent standard deviation on the mean. The position of the membrane is represented by the yellow slab. The gray, shaded region shows where the PB solution is not well defined. The profiles show three major modulatory electrostatic domains in Kirs: (1) the cytoplasmic domain, (2) the membrane interface, and (3) the cavity.

The cytoplasmic domain resides approximately between −60 Å < Z < −30 Å and in the case of the mammalian Kirs, provides an appropriate electrostatic environment for the stabilization of cations. The prokaryotic KirBac1.1 differs from the mammalian channels, showing minimal stabilization and even a small barrier at the cytoplasmic entrance (Robertson and Roux, 2005). The second electrostatically significant region is located from −30 Å < Z < −10 Å, coinciding with the cytoplasmic–membrane interface and appearing in the electrostatic profile as an energetic plateau that supports cation binding. Kir1.1/ROMK is an exception to this, with a repulsive barrier that might conflict with K+ conduction through the channel. The question of whether the Kir1.1/ROMK model represents a conductive state of the channel will be addressed later upon dissection of the molecular components involved. The final electrostatic domain is the transmembrane cavity, centered at Z = 0 Å and a high-affinity site for K+ in the strong rectifiers (Kir2.1/IRK and Kir3.1/GIRK), but it shows no cation stabilization in the weak rectifiers (KirBac1.1, Kir1.1/ROMK and Kir6.2/KATP). We now extend the electrostatic analysis of these structures further to dissect the molecular components involved in defining these profiles.

Reaction Field Energies in Kir Channels

We first calculate the electrostatic contribution of reaction fields in the ion channel environment. A reaction field occurs when a charge polarizes a high-dielectric medium thereby establishing a repulsive electric field at nearby low-dielectric interfaces. In the case of an ion channel system, there are two reaction field terms that can be separated from the PB equation.

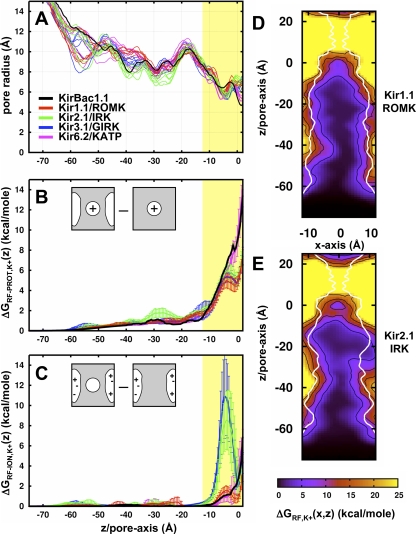

The first is the field created by the protein dielectric in response to the ion charge and can be calculated directly by solving the potential field for an ion in the channel plus membrane with all of the protein charges turned off, then subtracting the field created by the ion alone in the high dielectric. This energy is equal to ΔGRF-PROT = 1/2A(z)Qion2, where A(z) is a position-dependent function affected by the geometry of the channel plus membrane. The pore geometry is calculated for each channel in Fig. 3 A, showing similar profiles because they were all built on the same structural template. The ΔGRF-PROT energy profiles are in Fig. 3 B and show little energy contribution wherever the pore radius is wider than 7 Å. One position, Z = −30 Å, shows a slight increase in the reaction field energy in Kir2.1/IRK, corresponding to the “G-loop” constriction in the cytoplasmic domain (Pegan et al., 2005). This is partly because the channel contains a bulkier methionine at position 301, as opposed to the smaller alanine in Kir1.1/ROMK, changing the dielectric boundary enough to produce a difference both in the radius and ΔGRF-PROT profiles. There is a gradual increase in repulsive energy as the ion approaches the low-dielectric membrane slab. At the center of the cavity, the reaction field contribution is considerable, leading to a destabilization of ion binding at this position. Kir6.2/KATP shows a more pronounced repulsion due to a bulkier L157 that is not present in the other channels. Even though the putative open state of these channels forms a high-dielectric cavity inside the membrane, it is only wide enough to partially reduce the energetic penalty of transferring an ion into the low dielectric. This is expected of most ion channels and is in accord with previous electrostatic analysis of open K+ channel models (Jogini and Roux, 2005).

Figure 3.

Reaction field energetics of K+ in the Kir channel pore. (A) Radius profiles along the pore of the Kir channel models as calculated by the method described by Jogini and Roux (2005). The position of the membrane is depicted by the yellow slab. (B) Average reaction field energy profiles due to the ion charge on the protein dielectric, ΔGRF-PROT,K+(z) (n = 1 for KirBac1.1, n = 12 for mammalian Kirs, and error bars represent standard deviation). This energy is calculated by the solution of two PB calculations as depicted in the cartoon, that of the ion in the channel dielectric (Qchannel = 0) minus that of the ion alone in the solvent. (C) Average reaction field energy profiles due to the protein charge on the ion dielectric, ΔGRF-ION,K+(z). This energy is that of an ion dielectric (Qion = 0) in the channel minus that of the channel alone. (D and E) Total reaction field energies along the XZ cross section of (D) Kir1.1/ROMK (n = 1) and (E) Kir2.1/IRK (n = 3). A representative radius profile is plotted in white. Contour lines are plotted in black for 5, 10, 15, and 20 kcal/mole.

The second reaction field is the effect of the ion dielectric (εion = εprotein) in response to the protein charges and is calculated by determining the potential field for a neutralized ion in the charged channel system, then subtracting the field of the charged channel alone. The resultant energy shown in Fig. 3 C is not a function of ion charge, i.e., ΔGRF-ION = C(z), but is dependent on the ion dielectric and its proximity to protein charges. Typically, this energy term is negligible inside K+ channel pores (Roux and MacKinnon, 1999; Jogini and Roux, 2005). However, strongly rectifying Kir channels such as Kir2.1/IRK and Kir3.1/GIRK contain four aspartate residues in the cavity that are close enough to produce a significant reaction field. In this case, the charged residues close to the ion destabilize it slightly, resulting in the small barrier that is observed just below the cavity well in the total electrostatic interaction free energies of the strong rectifiers in Fig. 2. Because this electrostatic term depends on the proximity of the ion to the protein charges, it is sensitive to nearby structural variations. To ascertain the effect of those variations, an effort was made during the construction of the models to consider multiple positions for these charged residues (see Materials and methods). As is demonstrated by the large standard deviations observed in these profiles, changes in the position of these charged side chains yield substantial differences in the electrostatic energy. However, even with these deviations, the profiles of the strong rectifiers are still significantly different than those of the weak rectifiers. The results demonstrate that there is an energetic cost to bringing a positive ion into a cavity with negative charges, a feature that is selectively present in the strong rectifier channels.

Fig. 3 (D and E) shows the sum of these two reaction field energies, ΔGRF = 1/2A(x,z)Qion2 + C(x,z), for K+ along the XZ cross sections of the Kir1.1/ROMK and Kir2.1/IRK pore. The reaction field contribution increases as the ion moves off the central axis and closer to the protein, particularly in constricted regions such as the upper entrance of the cytoplasmic domain and the transmembrane cavity. At the center of the cavity, the combined reaction fields alone define an ion-localization site in Kir2.1/IRK that is not observed in the weak rectifier Kir1.1/ROMK. In general, the single-ion reaction field energy landscape effectively restricts the ion-accessible volume by creating a repulsive energetic buffer at the protein boundaries and in the strong rectifiers, a localizing site inside the cavity. This acts on the ions to push them away from the protein toward the center of the pore, potentially acting as a driving force promoting single filing. We do not believe that this repulsion is strong enough to account for the full single-filing behavior expected in the long-pore of Kir channels (Shin et al., 2005), but it does bring attention to one repulsive electrostatic component that is involved. Ultimately, multi-ion simulations must be performed and equilibrium ion distributions determined to examine the full nature of single filing in Kir pores.

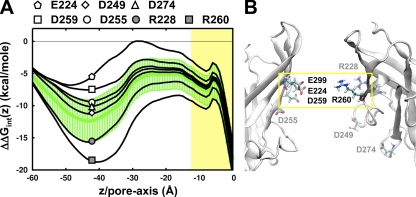

The Protein Static Field in Kir Channels

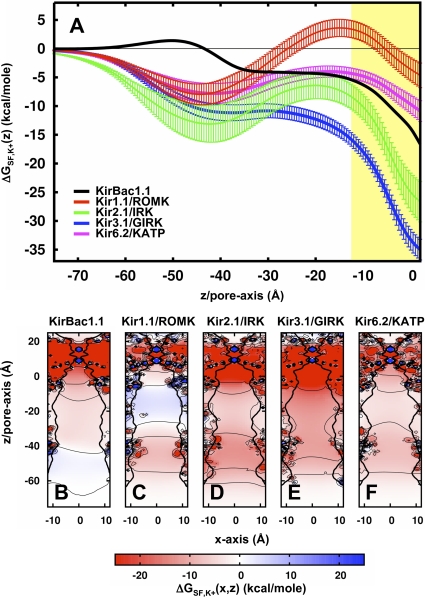

The remaining component of the electrostatic free energy is the dominant effect that comes from the potential field that is established by the static protein charge distribution. This is calculated by solving the PB equation for the channel system alone with all of the protein charges defined. The energy of an ion in that static field, ΔGSF, is then obtained by multiplying the charge of the ion by the value of this field at a given position. The ΔGSF profiles for K+ along the z axis of each Kir channel are calculated and shown in Fig. 4 A, and the maps along the XZ plane are shown in Fig. 4 (B–F). From the cytoplasmic domain to the membrane interface, the profiles are comparable to the total interaction energies shown in Fig. 2. Therefore, the general variability in the profiles, notably the repulsive energetics of Kir1.1/ROMK, is a consequence of differences in charge distribution through sequence variation. At the cavity, the static field is always stabilizing for K+, the strength of which shows a clear relationship with strength of rectification: Kir3.1/GIRK < Kir2.1/IRK < KirBac1.1 < Kir6.2/KATP < Kir1.1/ROMK. In the case of the weak rectifiers, the static field just balances the repulsive reaction field, enabling K+ to enter the transmembrane pore. For the strong rectifiers, there is an excess static field resulting in the formation of a strongly favorable binding site for K+ in the cavity. To investigate how sequence variation affects these features of the static field profile, we separate the static field energetics into contributions from each residue.

Figure 4.

Static field energetics of K+ in the Kir channel pore. (A) Average static field energy of K+ along the pore, ΔGSF,K+(z) (n = 1 for KirBac1.1, n = 12 for mammalian Kir channels, and error bars represent the standard deviation). The yellow slab depicts the membrane position along the pore. (B–F) Static field energy maps along the XZ cross section of each channel (n = 1 for KirBac1.1, n = 12 for mammalian Kirs). Contour lines are plotted with thin black lines for −20, −10, 0, 10, and 20 kcal/mole. Representative radius profiles are plotted with a thick black line.

Static Field Decomposition by Domain

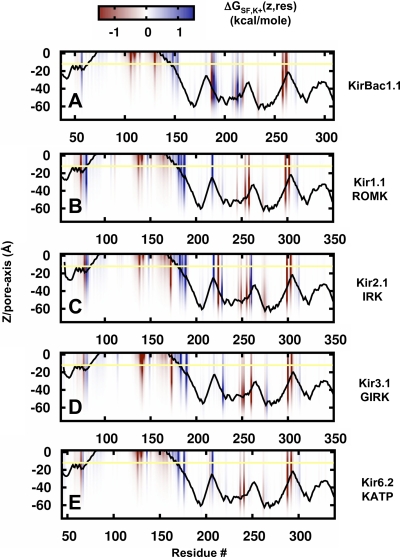

The total static field energy can be expressed as a sum of the energies of the ion in the individual field created by every charged atom in the system (Faraldo-Gomez and Roux, 2004; Jogini and Roux, 2005). From this, the static field energy contribution for each residue in the channel, ΔGSF(res,z), can be isolated from the total energy. This decomposition is performed for each residue at every position along the pore and is shown in Fig. 5 (A–E). One may note that ΔGSF(res,z) represents the sum of the static field energy from four residues, one from each subunit arranged symmetrically around the pore. At first sight, these plots look very similar for the different Kir channels, indicating a common electrostatic “footprint” along the pore. Presumably, this reflects the existence of a conserved set of charged residues among the channels that is likely necessary for maintaining structural features as well as for basic K+ conduction properties. Another observation is that individual residues contribute to the pore electrostatics over extended distances, indicated by the vertical span of colored bars in the figure, which persists when the protein dielectric constant is increased to 10 (Fig. S1). A list of all residues contributing >1.0 kcal/mole is listed in bold in Tables I–IV, organized according to their position in the channel structure. From this analysis, a total of 43 positions can be described as electrostatically active in Kir (as depicted in Fig. 1 A). Among these, fewer than half are conserved at the level of 80%, leaving the remaining residues as modulatory or discriminating sites. We proceed with a detailed analysis of each domain to determine the electrostatic formula that defines the ion energetics in each channel.

Figure 5.

Static field decomposition per residue along the pore. (A–E) The static field energy is plotted as a function of residue number and ion position along the pore, ΔGSF,K+(z,res). The contribution of each residue in the sequence is displayed in a red-to-blue smear according to the magnitude of the energy contribution at the different position z along the pore axis (n.b., the energy represents the sum contribution from four residues, one from each subunit). For example, in Kir1.1/ROMK, residue K80 makes an unfavorable contribution (blue) for positions extending from z = 0 to z = −62 Å; in Kir2.1/IRK, residue D172 makes a favorable contribution (red) for positions extending from z = 0 to z = −55 Å. The results represent averages over 12 structures for the mammalian Kir channels, where n = 1 for KirBac1.1. The yellow line represents the position of the cytoplasmic membrane interface.

TABLE I.

Pore Helix, Selectivity Filter, and Extracellular Loop Residues Contributing >1 kcal/mole Static Field Energy to the Interaction of K+ along the Pore for Z < 0 Å

| Pore helix, selectivity filter, and extracellular loops | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KirBac1.1 | I89 | V105 | E106 | T107 | L108 | A109 | T110 | V111 | D115 | M116 | P118 |

| Kir1.1 | E111 | L136 | E137 | T138 | Q139 | V140 | T141 | I142 | F146 | R147 | E151 |

| Kir2.1 | A115 | I137 | E138 | T139 | Q140 | T141 | T142 | I143 | F147 | R148 | D152 |

| Kir3.1 | K114 | I138 | E139 | T140 | E141 | A142 | T143 | I144 | Y148 | R149 | D153 |

| Kir6.2 | P102 | I125 | E126 | V127 | Q128 | V129 | T130 | I131 | G135 | R136 | E140 |

Residues are aligned across the five Kir channels to show the variation at each position between strongly contributing residues (bold) and non-electrostatic counterparts (italics). The yellow spheres in Fig. 1 A highlight the positions of these 11 sites.

TABLE II.

TM2 Residues Contributing >1 kcal/mole Static Field Energy to the Interaction of K+ along the Pore for Z < 0 Å

| TM2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KirBac1.1 | E130 | I131 | M135 | I138 | T142 |

| Kir1.1 | Q163 | S164 | V168 | N171 | C175 |

| Kir2.1 | Q164 | S165 | C169 | D172 | I176 |

| Kir3.1 | Q165 | S166 | S170 | D173 | I177 |

| Kir6.2 | Q152 | N153 | L157 | N160 | L164 |

Residues are aligned across the five Kir channels to show the variation at each position between strongly contributing residues (bold) and non-electrostatic counterparts (italics). The green spheres in Fig. 1 A highlight the positions of these five sites.

TABLE III.

Cytoplasmic Membrane Interface Residues Contributing >1 kcal/mole Static Field Energy to the Interaction of K+ along the Pore for Z < 0 Å

| Cytoplasmic membrane interface | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KirBac1.1 | K57 | S59 | P61 | F63 | R148 | R151 | — | R153 | Q182 |

| Kir1.1 | D74 | K76 | R78 | K80 | K181 | R184 | K187 | R188 | K218 |

| Kir2.1 | D78 | R80 | R82 | M84 | K182 | K185 | K188 | R189 | K219 |

| Kir3.1 | D77 | K79 | R81 | N83 | K183 | Q186 | K189 | R190 | N220 |

| Kir6.2 | D65 | K67 | P69 | T71 | K170 | Q173 | R176 | R177 | K207 |

Residues are aligned across the five Kir channels to show the variation at each position between strongly contributing residues (bold) and non-electrostatic counterparts (italics). The blue spheres in Fig. 1 A highlight the positions of these nine sites.

TABLE IV.

Cytoplasmic Domain Residues Contributing >1 kcal/mole Static Field Energy to the Interaction of K+ along the Pore for Z < 0 Å

| Cytoplasmic domain | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KirBac1.1 | E187 | R189 | K191 | K208 | — | D211 | K213 | V215 | R216 | |||||||||

| Kir1.1 | G223 | H225 | Y227 | L244 | N248 | N250 | V252 | D254 | A255 | |||||||||

| Kir2.1 | E224 | H226 | R228 | L245 | D249 | N251 | G253 | D255 | S256 | |||||||||

| Kir3.1 | S225 | Q227 | R229 | L246 | E250 | D252 | G254 | S256 | T257 | |||||||||

| Kir6.2 | S212 | T214 | H216 | L233 | D237 | P239 | E241 | G243 | V244 | |||||||||

| Cytoplasmic domain

|

||||||||||||||||||

| KirBac1.1 | E218 | H219 | P220 | D233 | S235 | E258 | D261 | E262 | R271 | |||||||||

| Kir1.1 | N257 | E258 | N259 | D273 | N275 | D298 | V301 | E302 | R311 | |||||||||

| Kir2.1 | I258 | D259 | R260 | D274 | D276 | E299 | V302 | E303 | R312 | |||||||||

| Kir3.1 | A259 | D260 | Q261 | D275 | K277 | E300 | V303 | E304 | R313 | |||||||||

| Kir6.2 | G246 | N247 | S248 | D262 | N264 | E288 | V291 | E292 | R301 | |||||||||

Residues are aligned across the five Kir channels to show the variation at each position between strongly contributing residues (bold) and non-electrostatic counterparts (italics). The red spheres in Fig. 1 A highlight the positions of these 18 sites.

I. The Pore

The pore contains 11 residues that contribute strongly to ion energetics along the central permeation axis (Table I and Fig. 1 A, yellow spheres). The sum of the energy profiles from these components creates a long-range attractive potential that stabilizes the ion as it approaches the low-dielectric membrane (Fig. 6 A). This is present in each of the Kir channels, demonstrating a conservation of favorable static field in the cavity that offsets the repulsive energy conferred by the reaction fields (Fig. 3, B and C). This effect corresponds to the electrostatic stabilization that is present in the cavity of KcsA (Roux and MacKinnon, 1999; Jogini and Roux, 2005). Most of the residues involved are located in the pore helix or bottom of the selectivity filter and are in close proximity with the cavity. Although these residues are uncharged, their position still allows for significant electrostatic effects from side chain or backbone partial charges. In general, the effects from these residues are much more subtle and closer to the arbitrary 1.0 kcal/mole cutoff, which is why certain residue positions exhibit a remarkable ability to distinguish between very similar side chains. For example, T141 in Kir2.1/IRK falls just below the cutoff compared with valine at the same position in other channels. Although both side chains are similar in size and overall neutral, there is a focused positive charge on the hydroxyl group of threonine, which in turn produces a difference in the static field effect compared with valine. Numerous mutagenesis studies have demonstrated that these residues modulate ion energetics, either through permeation or divalent blockade (Zhou et al., 1996; Chatelain et al., 2005), in agreement with our analysis of the electrostatic significance of residues at these positions.

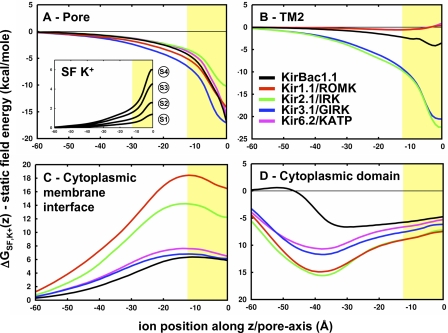

Figure 6.

Strong static field profiles in each structural domain. The sum profile of the strongly contributing residues is divided into the following structural domains: (A) the pore, (B) TM2, (C) the membrane interface, and (D) the cytoplasmic domain. The inset in A shows the contribution from an ion in each selectivity filter binding site. The profiles are averages for the mammalian Kir channels (n = 12). The yellow slab depicts the position of the membrane along the pore.

There are also several charged residues present in the Kir pore that are not typically present in other K+ channels. As mentioned previously, there is a putative glutamate/arginine pair (e.g., E138/R148 in Kir2.1/IRK) in the mammalian Kir channels (Yang et al., 1997) that strongly affects the electrostatics near the pore. Note that we imposed the salt bridge in only half of our models (see Materials and methods), indicating that the overall result is not dependent on the precise structure of these residues. In contrast, the prokaryotic KirBac1.1 does not contain the extracellular arginine and instead has a glutamate/aspartate pair (E106/D115) that is homologous to KcsA (Berneche and Roux, 2000; Zhou et al., 2001). From this, we expect that one of these residues is protonated and involved in a hydrogen-bonded interaction behind the pore, resulting in the destabilization of the electrostatic energy for K+ in the cavity of KirBac1.1. One other charged residue exists, E141 in the lower pore helix of Kir3.1/GIRK, but it is specific to this channel. Mutagenesis studies at this position suggest that its principal role is in gating (Guo and Kubo, 1998; Alagem et al., 2003) and that it does not affect K+ permeation or selectivity, in contrast with what would be expected for a charged residue so close to the pore. It is possible that this residue is either in its neutral protonated form or that structural perturbation by the mutation changes its electrostatic significance.

There is an additional key pore contribution present in all K+ channels: the ions inside the selectivity filter. A K+ ion in any of the four binding sites has an effect on the electrostatic energy of other ions inside the channel (Fig. 6 A, inset). From this, it can be seen that an ion at the cavity with filter configuration S1/S3 is stabilized by ∼2.5 kcal/mole compared with filter ions in S2/S4. Here, we limit our calculations to S1/S3 configurations.

II. TM2

There are five residues in TM2 that contribute strongly to the electrostatic profile along the pore (Table II and Fig. 1 A, green spheres). The sum potential from these residues differentiates Kir channels into two types of TM2 electrostatics: weak or strong attractors that correspond to their physiological rectification strength (Fig. 6 B). The favorable electrostatics in the strong rectifiers comes from a well-known negatively charged residue D172 in Kir2.1/IRK and D173 in Kir3.1/GIRK, which in experiments has been identified as a key rectification controller and putative site for blocker binding (Lu and MacKinnon, 1994; Stanfield et al., 1994; Wible et al., 1994). The absence of favorable TM2 electrostatics is a feature of the weak rectifiers, which leads to the prediction that KirBac1.1 is also a weak rectifier. However, it may not be this simple because KirBac1.1 contains an additional charge in the upper TM2, E130, which is present as glutamine in all of the mammalian channels. This residue is farther from the pore compared with the strong rectifier cavity aspartates, and thereby contributes weaker stabilization along the pore. Still, the profile is more favorable than the weak rectifiers and it would be interesting to examine the role of this residue and the significance of the extra negative field on ion permeation or block. The remaining three cavity-lining residues at positions 165, 169, and 176 in Kir2.1/IRK are uncharged but close enough to contribute significant electrostatic effects. Extensive studies of mutations at these positions support the collective argument that the residues in TM2 near the cavity are in position to affect ion energetics and block (Minor et al., 1999; Thompson et al., 2000; Fujiwara and Kubo, 2002; Chatelain et al., 2005).

III. The Membrane Interface

At the cytoplasmic membrane interface, there are nine residue positions on the channel exterior that exert a significant effect on ion energetics inside the pore (Table III and Fig. 1 A, blue spheres). These residues come from the N terminus/slide helix, TM1, TM2 cytoplasmic linker, and a residue from the outside of the cytoplasmic domain. The sum from these residues produces a strongly repulsive profile that is centered at the cytoplasmic membrane interface (Fig. 6 C).

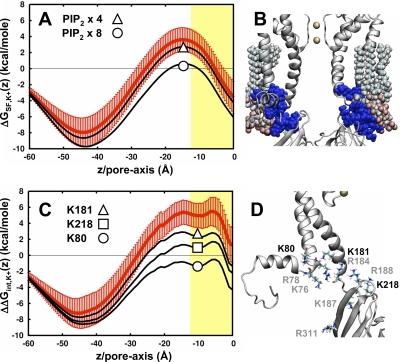

Out of the nine, five are positively charged residues that have been experimentally identified as interaction partners with PIP2, a modulator of gating in all Kir channels (Huang et al., 1998; Hilgemann et al., 2001; Lopes et al., 2002). If these residues form a binding interface, it is possible that PIP2 (charge = −4) interacts and shields the repulsive electrostatics inside the pore. To examine this, PIP2 is modeled onto Kir1.1/ROMK by positioning the phosphoinositol head group at the center of mass of the positively charged residues, followed by a minimization while spherically restraining the movement of the lipid. The static field along the pore is then calculated with four or eight PIP2 molecules per channel (Fig. 7 A). We find that the addition of PIP2 does not substantially affect the barrier until two molecules are added per subunit (Fig. 7 B). This corresponds to the fact that there is an excess of positively charged residues in this region, and that PIP2 interacting with the channel from the outside has weaker electrostatic effects than the charges directly on the channel. This is only a cursory examination into the electrostatic effects of PIP2, and atomic-level resolution of the binding structure is required for proper study of this question. Recently, a structure of the chimera of Kir3.1/GIRK and KirBac3.1 was determined at high resolution with PIP2 analogues bound to the putative binding pocket (Nishida et al., 2007). However, this channel is believed to be in a closed state, and the PIP2 positions are not necessarily relevant to the open state modeled here.

Figure 7.

Electrostatic modulation at the membrane interface of Kir1.1/ROMK. (A) Static field profiles in the presence of PIP2. (B) Kir1.1/ROMK pore with two PIP2 molecules “bound” to each subunit. Two subunits are removed for clarity of the pore. The positively charged residues that contribute to the repulsive electrostatics at the membrane interface are shown in blue. (C) The static field contributions from several positive residues are subtracted from the total interaction energy (red): K181 (triangle), K218 (square), and K80 (circle). The values subtracted are averaged over 12 different calculations. (D) A single subunit of Kir1.1/ROMK, focusing on the positive residues near the membrane interface. The residues “mutated” in A are shown in bold text, whereas the residues shown in gray contribute less than that of K181.

As shown in Figs. 4 and 6, there is a repulsive static field barrier, ∼4 kcal/mole, at the membrane interface that is specific to Kir1.1/ROMK. Out of the five channels, Kir1.1/ROMK is the only one to contain a positive charge at the location of residue K80 located at the base of TM1. Identification of this particular residue in the electrostatics is of significant interest because in experiments, K80 has shown to be one of the key regulators of pH-induced closure in Kir1.1/ROMK (Fakler et al., 1996; Choe et al., 1997; Leng et al., 2006). The electrostatic effect of neutralizing this residue (Fig. 7 C) shows that subtraction of this contribution is enough to cancel the barrier in the total interaction energy of Fig. 2 and thus produce an energetic profile that stabilizes K+ along the entire pore. Examining the effect of all other positive residues in the channel, including those involved with PIP2 binding, reveals that K80 is unique in its ability to remove the barrier, although K218 on the cytoplasmic domain results in a considerable reduction as well.

The repulsive effect of K80 on the pore electrostatics suggests that it might be neutral in the conductive channels. To examine this further, the ΔpKa values were calculated as described by Jogini and Roux (2005). In the current system definition, there is little shift in the pKa, suggesting that the lysine remains in its charged state. This is because the residue is exactly at the membrane interface (see Cα(z) profile in Fig. 5 B), and the side chain of the lysine preferentially partitions into the high dielectric during the model construction. Burying the residue by changing the membrane definition from −12.5 Å < Z < 12.5 Å to −20 Å < Z < 12.5 Å results in a shift of the pKa to ∼7, indicating that it could be neutral depending on the structure of the low dielectric in this region. The 25-Å initial width of the membrane is only an approximation, and a 7.5-Å increase of the hydrophobic core is within reason as biological membrane thickness can increase depending on the lipid composition as well as structural accommodation around proteins. Collectively, our results suggest that both protonation states of K80 are possible depending on the local geometry of the membrane, and that the stabilization of an ion inside the pore is strongly coupled to the charge state of this residue.

IV. The Cytoplasmic Domain

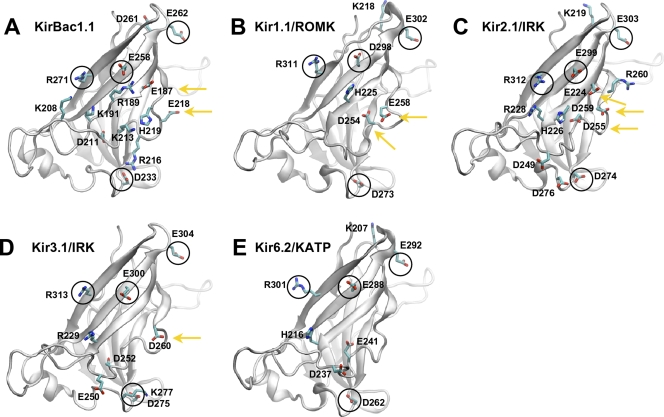

The cytoplasmic domain contains the majority of strongly contributing residues, with 18 positions distributed across the five channels (Table IV and Fig. 1 A, red spheres). Collectively, these residues produce a favorable electrostatic environment for cations inside the cytoplasmic pore of the mammalian channels, but not in the prokaryotic KirBac1.1 (Fig. 6 D). The positions of these residues along the pore-lining surface are shown on a single subunit of each channel in Fig. 8 (A–E). From this, it can be seen that four of these residues (D233, E258, E262, and R271 in KirBac1.1; Fig. 8, circled residues) are completely conserved. The sum of their contributions accounts for the general favorability found inside the cytoplasmic pore, producing a chevron-like profile of favorable static field energy stabilizing K+ along the entire length of the channel (Fig. 9 A).

Figure 8.

Strongly contributing residues in the cytoplasmic domain. (A–E) Strongly contributing residues are mapped onto a single subunit of the cytoplasmic domain for each Kir channel. The identities of the residues are labeled as shown. The black circles designate the residues that are conserved across each of the channels. Residues highlighted by the yellow arrows are the strongest negatively charged contributors located in the central core of the domain. Histidines are highlighted for reference, although they are neutral in these calculations.

Figure 9.

Conserved and “signature” electrostatics in the cytoplasmic domain. The cytoplasmic profile from Fig. 6 D is further separated into the contribution from conserved residues (A) and the “signature” profile comprised of the remaining strong residues individual to each channel (B). The profiles are averages for the mammalian Kir channels (n = 12). The yellow slab depicts the position of the membrane along the pore.

The remaining strongly contributing, nonconserved residues in the cytoplasmic domain comprise a profile that we refer to as the “cytoplasmic signature” that is specific to each channel (Fig. 9 B). Here, we see that KirBac1.1 is distinctively different from the mammalian Kir channels, yielding a repulsive profile that is brought about due to an excess of positively charged residues throughout the pore: R189, K191, K208, K213, and R216 (Fig. 8 A). In contrast, all of the mammalian profiles are favorable and can be separated into two subgroups of cytoplasmic stabilization, with Kir1.1/ROMK and Kir2.1/IRK more favorable than Kir3.1/GIRK and Kir6.2/KATP. In the case of Kir6.2/KATP, only two negative residues at the inner opening of the cytoplasmic domain, D237 and E241, contribute to form the weaker profile in Fig. 9 B. Residues like these located at the cytoplasmic entrance (Z < −40 Å) are farther away from the pore (see radius profiles in Fig. 3 A), more exposed to the bulk, and shielded by the high dielectric. In contrast, even though the profile of Kir1.1/ROMK is also composed of just two residues, D254 and E258 (Fig. 8 B), they are located inside the central pore (−40 Å < Z <−30 Å) of the cytoplasmic domain resulting in the stronger stabilization. Because this region is more enclosed by the low-dielectric protein, the static fields from residues in these positions are stronger than those at the cytoplasmic entrance. Kir3.1/GIRK modulates the distribution of charges between these two regions, with one negative residue in the central pore (D260) and three in the cytoplasmic entranceway (E250, D252, and D275). However, it has an additional positive residue, R229, lining the pore (Fig. 8 D). The low density of negative residues in the center of the pore, along with the contribution from the positive charge, results in a weaker profile that is more similar to that of Kir6.2/KATP. Among the four channels, Kir2.1/IRK has the most electrostatically complex cytoplasmic domain, with seven residues contributing to its “signature” profile. It contains a high density of negative residues in the central pore (E224, D255, and E258), two negative residues in the cytoplasmic entrance (D249 and D274), and two positive residues throughout (R228 and R260; Fig. 8 C).

The significance of residue position and its impact on the electrostatic profile is best demonstrated by looking at the effect of in silico mutations in a strongly charged channel like Kir2.1/IRK (Fig. 10). Here, we approximate the effect of neutralizing a charged residue by subtracting that contribution from the total electrostatic interaction energy profile. The “mutation” of residues around the cytoplasmic entrance (D249, D274, and D255) results in a mild destabilization that is isolated to the central pore. The results correspond with the experimental findings that these residues have little effect on rectification affinity and are therefore not part of the actual blocking site (Taglialatela et al., 1995; Pegan et al., 2005; Fujiwara and Kubo, 2006). Recently, it was determined that D255 affects the kinetics of rectification block (Kurata et al., 2007), indicating that these residues might participate in increasing the local concentration of blocker cations. In contrast, residues inside the central pore, such as D259, E224, and E299, have significant long-range effects on the electrostatic profile throughout the channel. In particular, E224, one of the first cytoplasmic residues found to affect rectification affinity (Taglialatela et al., 1995; Yang et al., 1995), appears to be in a critical position for defining pore electrostatics. Removal of negative charge at this particular position not only destabilizes K+, but also changes the qualitative features of the landscape and even introduces a barrier around Z = −30 Å. D259, which destabilizes but still preserves the overall energetic landscape, has been experimentally shown to affect rectification affinity, but less so compared with E224 (Pegan et al., 2005; Fujiwara and Kubo, 2006). For the positive residues in the pore, subtraction of their contributions produces an increased stabilization with both R228 and R260, although R260 is much more substantial as it is situated close to E224 and E299 in the central core of the domain. Experimental studies involving mutations of these positive charges show little effect on rectification (Zhang et al., 2004; Pegan et al., 2005; Fujiwara and Kubo, 2006), although conductance changes have been observed with neutralization of R260 (Zhang et al., 2004). The modulation of conductance is in line with a change in electrostatics in the pore, but it is surprising that these perturbations do not affect rectification as well (see Discussion).

Figure 10.

In silico mutagenesis in the cytoplasmic domain of Kir2.1/IRK. (A) The effect of in silico mutations of key cytoplasmic domain residues on the interaction energy along the pore of Kir2.1/IRK. (B) Significant electrostatic residues inside the cytoplasmic pore. Two subunits are removed for clarity. The yellow box designates the central core of the cytoplasmic domain.

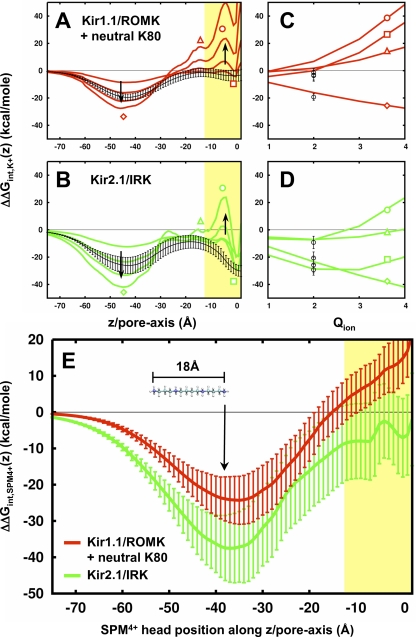

Multivalent Ion Energetics in Kir Channels: Electrostatic Implications on Nonspecific Charge Selectivity and Rectification Block

The analysis up until now has been for monovalent K+, but these results can be extended to examine the energetics of ions with higher charge. As described previously, the electrostatic interaction energy of a single ion is a quadratic function of the ion charge, ΔΔGint = 1/2AQion2 + BQion + C (Eq. 7, Materials and methods). We have already calculated the parameter fields for a K+ ion along the pore axis of each channel: A(z), protein reaction field (Fig. 3 B); B(z), protein static field (Fig. 4 A); and C(z), ion reaction field (Fig. 3 C). By plugging these functions into the above ΔΔGint equation, we can determine the energy profiles for similar probe ions with different magnitudes of charge. The electrostatic interaction energy profiles for ions of charge Qion = 1 to Qion = 4 are shown for Kir1.1/ROMK plus neutral K80 (Fig. 11 A) and Kir2.1/IRK (Fig. 11 B). In addition, the energy as a function of charge is plotted for both channels for an ion at different positions along the pore: the cytoplasmic domain (Z = −45 Å), the membrane interface (Z = −20 Å), the entrance to the cavity (Z = −5 Å), and the cavity (Z = 0 Å; Fig. 11, C and D).

Figure 11.

Multivalent ion energetics in Kir. (A and B) Interaction energy profiles are shown for an ion (radius equal to rK+) of charge Qion = 1 to Qion = 4 for Kir1.1/ROMK plus neutral K80 (A) and Kir2.1/IRK (B). The arrows show the direction of increasing charge. The black curve in each plot represents the average interaction energy for a smaller Mg2+ ion along the pore. (C and D) The interaction energy versus charge (Qion) relationship is plotted for Kir1.1/ROMK plus neutral K80 (C) and Kir2.1/IRK (D). The curves correspond to different positions along the pore as designated by the following symbols: z = −45 Å (diamond), z = −15 Å (triangle), z = −5 Å (circle), and z = 0 Å (square). The actual interaction energy for Mg2+ is plotted at Qion = 2 for comparison. (E) The electrostatic interaction energy for SPM4+ along the pore of Kir1.1/ROMK plus neutral K80 and Kir2.1/IRK. SPM4+ is in its extended form (∼18 Å in length) and is aligned along the z axis, where the z-value corresponds to the position of the SPM4+ head group. All profiles are averages over n = 12, with the error bars representing standard deviation on the mean.

Both channels show a preference for higher charge species inside the cytoplasmic domain. At Z = −45 Å, the energy versus charge relationship is negative and linear, indicating that the static field dominates the overall energetics. For the TM pore in Kir1.1/ROMK plus neutral K80, the reaction field is the dominating term and contributes an increasing energetic penalty for transferring ions with charge Qion > 1 into the channel. Alternatively, there is a balance in the reaction and static field contributions in the cavity of Kir2.1/IRK, resulting in stabilization of a range of charges from Qion = 1 to Qion = 4. The reaction field in both channels introduces a barrier before the cavity when the charge of the ion is increased, which might correspond to kinetic differences between conducting ions and blockers of different charge (Lu, 2004). Based on these results, Kir1.1/ROMK plus neutral K80 is electrostatically suited for the interaction of K+ but not higher charges, whereas Kir2.1/IRK can accommodate charges up to Qion = 4. Kir3.1/GIRK and Kir6.2/KATP show similar results corresponding to their strength in rectification (not depicted). This demonstrates an electrostatic mechanism of nonspecific charge selectivity for ions near the cavity region of weak and strong rectifier channels.

The Mg2+ interaction energy profiles are shown in black in Fig. 11 (A and B) and correspond generally to the Qion = 2 profiles, with small deviations as the ion approaches the TM cavity. The reason for this is that the Mg2+ ion has a smaller Born radius, which results in a smaller ion dielectric–dependent reaction field energy (Fig. 11, C and D, black circles). The charge dependency of Kir1.1/ROMK for Z > −25 Å suggests that K+ is able to compete with Mg2+ throughout the TM pore. On the other hand, the strong rectifier Kir2.1/IRK shows a preferential interaction of Mg2+ over K+ at the cavity, which supports the hypothesis that this is a Mg2+ block site (Lu and MacKinnon, 1994).

The relationship shown in Fig. 11 D indicates that an ion with a valence of Qion = 4 does not interact more favorably than a monovalent ion inside the cavity. Of course, rectification polyamines like SPM4+ are long (∼18 Å) and more complex than a simple point charge. Nevertheless, simple electrostatic considerations do not readily explain why a strongly charged species binds competitively over K+ at the cavity. The electrostatic interaction free energy of an extended SPM4+ molecule is calculated along the pore of Kir1.1/ROMK plus neutral K80 and Kir2.1/IRK and is shown in Fig. 11 E. In both channels, the profiles show a global minimum inside the cytoplasmic domain that is significantly more favorable than any other position along the pore. In Kir1.1/ROMK, there is a barrier for SPM4+ entry as it approaches the membrane, whereas Kir2.1/IRK provides some stabilization at the center of the cavity. However, the interaction energy for the extended SPM4+ is still less favorable than K+ (Fig. 2). To examine whether different ion configurations in the filter might affect these results, the Kir2.1/IRK profiles for K+ and SPM4+ are also calculated with ions in S2/S4 as well as no ions in the filter (Fig. S2, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200810068/DC1). The preference for K+ at the cavity is consistent for all filter configurations; however, SPM4+ begins to approach K+ energy values when ions are removed from the filter. Therefore, the binding energy appears dependent on filter occupancy, corresponding to both voltage dependence and external K+ competition that is characteristic of strong rectification (Hille and Schwarz, 1978; Hille, 2001), but it does not change the overall result that K+ is electrostatically favored over SPM4+. Experimental studies of gated access and polyamine trapping demonstrate that these rectification blockers interact inside the cavity (Kurata et al., 2006). Therefore, it is likely that changes in conformation of SPM4+ in the blocked state, direct protein–SPM4+ interactions, conformational changes of the channel, and perturbations of the multi-ion distribution inside the channel are also important to consider when calculating the binding energies of blockers.

DISCUSSION

Advantages and Limitations of Continuum Electrostatics Calculations

The PB calculations reported here connect the structural features of Kir channels to the energetics of an ion inside the pore, providing the necessary groundwork for investigating more complicated functions such as conduction and rectification blockade. The overall agreement with experimental mutational data supports the models and results; however, it is evident that the study has certain limitations. First, the structures are homology models based on a template with <30% sequence identity, entailing an inherent level of uncertainty. Furthermore, the template is a closed-state crystal structure of 3.65-Å resolution (Kuo et al., 2003), fit onto a 9-Å resolution 2D electron crystallography density of the open state (Kuo et al., 2005). Other groups have attempted to study similar models with full atomistic molecular dynamics simulations (Domene et al., 2005, 2008; Haider et al., 2007), inferring results about conformational dynamics and specific residue interactions. However, it is difficult to be confident about such results because the low resolution of the initial structures makes it implausible to draw conclusions at the atomic level. On the other hand, it should be emphasized that continuum PB calculations depend mainly on the long-range electrostatic features of a system and are not particularly sensitive to small angstrom–scale details. This is indicated by the fact that our calculations are based on 12 structural models for each channel, spanning an rmsd of ∼3–4 Å, yet in most cases, the standard deviation on the mean is still sufficiently small enough to allow us to determine significant differences in key features of the various profiles. The accuracy of the calculations is optimized by limiting the analysis to appropriately wide regions of the channel where the calculations are well defined, as discussed in Allen et al. (2004). Finally, we interpret our results comparatively, with the results of each Kir channel effectively acting as a control for the others. By choosing a modeling approach justified for the level of detail of our models and applying our analysis within appropriate limits, we have been able to demonstrate key physical features of Kir channels that we believe are valid even with limited structural information.

The Cytoplasmic Domain

The electrostatics analysis suggest that the cytoplasmic domain is an important component of the ion conducting pathway that extends the low dielectric into the cytoplasm, potentiating the pore electrostatics and providing a scaffold for charged residues to focus a strong negative static field. Recently, high-resolution x-ray crystal structures of inward rectifiers have shown localized ion densities around the cytoplasmic pore. First, the KirBac3.1/Kir3.1-GIRK chimera shows ions in the selectivity filter, cavity, and two densities close to the upper opening of the cytoplasmic domain, referred to as the “G-loop” (Nishida et al., 2007). It is not well understood how these ions are localized because nearby residues are uncharged. Still, the cytoplasmic domain in these structures is more constricted compared with our models and may allow for some specific coordination. An additional study of the excised cytoplasmic domain of Kir2.1/IRK shows a K+ ion with its hydration shell at the inner entrance near residue D255 (Pegan et al., 2006). In general, the isolated cytoplasmic domains exhibit a more compact, collapsed structure compared with when it is intact with the transmembrane domain. In our models of Kir2.1/IRK, D255 does contribute a significant effect but is still too far from the pore to specifically coordinate an ion. Because these recent structures do not reflect the open state of the channels, we did not study them here.

The fact that the pore radius is so large in the open state suggests that this is a concentrating region of the pore rather than a specific binding site for K+. Increasing the local concentration of K+ in the cytoplasm is beneficial in enhancing the physiological outward conductance. However, this domain is likely nonspecific because of its size and charge and could potentially collect other ions, such as Na+, that would inhibit conductance. In typical cells where these channels are expressed, the intracellular ratio of K+/Na+ is ∼10:1 (Hille, 2001). Assuming that there is no selectivity for one ion over the other, K+ will be the preferential monovalent occupying the pore. In the case of multivalent ions, the wide, strongly charged pore of the cytoplasmic domain shows electrostatic preference for higher charged species (Fig. 11). Intracellular concentrations of Ca2+ are very small (∼μM), whereas the ratio of K+/Mg2+ and K+/SPM4+ in the cytoplasm is ∼100:1 and 1,000:1, respectively. The electrostatic charge preference may be one factor that supports the sequestration of higher charged ions inside the pore over monovalent K+, which otherwise would be statistically uncommon in physiological ion conditions.

One interesting feature that arises from our analysis is that the cytoplasmic electrostatics for the weak rectifier Kir1.1/ROMK and strong rectifier Kir2.1/IRK are similar (Figs. 6 and 9). Experiments show that exchanging the two domains confers strong rectification to ROMK (Lu and MacKinnon, 1994; Taglialatela et al., 1994, 1995), which was largely attributed to residue E224 in Kir2.1/IRK that is present as G223 in Kir1.1/ROMK. Mutation of E224 to glycine substantially reduces rectification affinity for both Mg2+ and SPM4+ in Kir2.1/IRK; however, introduction of a glutamic acid at G223 in Kir1.1/ROMK has no clear effect (Taglialatela et al., 1995). Our analysis shows that these substitutions have quite different results on the electrostatics of the pore. The neutralization of E224 in Kir2.1/IRK removes an electrostatically stabilizing environment; however, because Kir1.1/ROMK is already favorable, the introduction of the additional negative charge into the pore does not confer stabilization but makes an already negative environment much more so. This also holds for mutations of positively charged residues R228 and R260 in Kir2.1/IRK, in which neutralization enhances the favorable energetics inside the cytoplasmic domain (Fig. 10). Experiments show little effect of these mutations on rectification (Pegan et al., 2005; Fujiwara and Kubo, 2006) and instead, R260 affects single-channel conductance (Zhang et al., 2004). It appears that removal of negative electrostatics in the cytoplasmic domain is capable of reducing rectification, but that increasing electronegativity does not have the corresponding effect. This suggests that in wild-type Kir1.1/ROMK and Kir2.1/IRK, the rectification mechanism is saturated with respect to the electrostatic potential in the cytoplasmic domain. Alternatively, it may reflect a more specific molecular interaction between the blockers and the pore. Kir1.1/ROMK and Kir2.1/IRK have similar cytoplasmic electrostatics but achieve this through very different molecular compositions (Fig. 8, B and C). Such interactions are beyond the scope of this study.

Pore Electrostatics at the Membrane Interface

The closed to open gating transition in potassium channels involves a conformational change in the lower transmembrane helices and formation of a pathway for the ion across the membrane (Jiang et al., 2002; Kuo et al., 2005). However, to support the high-throughput conductance that is present in these channels, it is not enough for the pathway to be sterically open; it must be electrostatically stabilizing for ions as well. In previous studies, it was shown that closing of the helices brings about a strong electrostatic repulsion at the membrane interface by way of the reaction field (Jogini and Roux, 2005; Robertson and Roux, 2005). In our open-state models, the reaction field energy is reduced enough in most cases to stabilize ions along the transmembrane pore. However, in Kir1.1/ROMK, we find an additional repulsive barrier due to the static field from a high density of positive charges, including K80, concentrated at the cytoplasmic membrane interface. As already mentioned, this residue is involved in PIP2 and pH-dependent gating, which is thought to entail a conformational change in the lower transmembrane helices (Schulte et al., 1998; Sackin et al., 2006), possibly involving changes in inter-helix hydrogen bonding (Rapedius et al., 2006, 2007). The lysine at position 80 is not necessary for pH gating per se, but it does affect the sensitivity to H+, bringing it into the physiological range. This modulation of the gating process might involve titration of the amino acid side chain, but our estimates of the pKa of K80 are not precise enough to verify this idea directly. Such a mechanism suggests the existence of titratable subconductance states. In fact, such states exist in both Kir.1.1/ROMK and Kir2.1/IRK with PIP2 depletion (Leung et al., 2000; Xie et al., 2008), and subconductances have been observed to occur during pH gating, although they have not been studied in detail (Choe et al., 1997). Despite these uncertainties, it is clear that the Kir1.1/ROMK channel will not conduct ions very well unless this residue is neutralized, either by increased cytoplasmic pH or by the presence of anionic phospholipids such as PIP2 (Fig. 7).

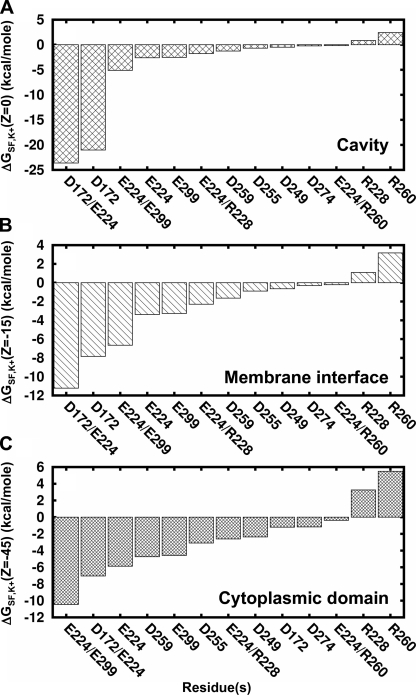

Implications of Long-range Electrostatics in Kir Channels

It is well known that long-ranged electrostatics is a key factor governing the behavior of ions inside channels (von Kitzing, 1999; Roux et al., 2000; Bichet et al., 2006). Electrostatics effects are, however, often difficult to grasp intuitively except in the case of the simplest geometries. For this reason, many aspects are not readily understood. Most experiments involving mutations of charged residues are interpreted by assuming that this type of perturbation is local, but our results imply that this assumption is not generally valid. In our static field decomposition shown in Fig. 5, we demonstrate that residues along the Kir channel pore can exert considerable effects, even up to 40 Å away. One reason for this is that the long pore of the Kir channel extends the low dielectric into the cytoplasm, potentiating the static field even though there is high-dielectric screening inside the pore. The effect persists, albeit with a reduced magnitude, even when the protein dielectric constant is increased to 10 (Fig. S1).

The electrostatic energy at any position within the pore must therefore be considered as a function of all of the other residues in the channel, not just those that are local to the region. For example, in the cytoplasmic domain analysis, the “signature profiles” for Kir1.1/ROMK and Kir2.1/IRK are nearly identical (Fig. 9), but the total static field in Kir2.1/IRK is more favorable (Fig. 4). Most of this difference comes from long-range contributions from TM2 (Fig. 6 B) and residues at the membrane interface (Fig. 6 C). In addition, Kir2.1/IRK contains a high density of negative residues near the cytoplasmic entrance (D205, D272, D275, and D276) that are far from the pore axis and thereby too weak to be considered individually as strong contributors but altogether produce a significant effect. This is important to consider, especially in the interpretation of previous chimera studies that typically exchange sequential parts of the gene rather than conserved electrostatic regions (Taglialatela et al., 1994, 1995; Zhang et al., 2004). This may explain why replacing the total cytoplasmic domains confers rectification and conduction behavior more accurately than do point mutations.

A final consideration is the impact of long-range electrostatics on the interpretation of residues affecting rectification affinity. Residues in the cytoplasmic domain and cavity are key controllers of rectification blockade. It was shown that the energetic contribution from these residues is additive and independent, i.e., they do not interact together to form a single binding site (Yang et al., 1995). This was further substantiated when the structure of a full-length Kir channel showed that these residues are ∼40 Å apart (Kuo et al., 2003). Our study demonstrates that long-range electrostatics could account for these experimental results. In Fig. 12, we plot the contributions of experimentally significant charged Kir2.1/IRK residues at three positions along the pore: the cavity (z = 0 Å), the membrane interface (z = −15 Å), and the cytoplasmic domain (z = −45 Å). At all positions, the general trend is that residues known to affect rectification (D172/E224, E224, E299, D172, and D259) contribute the strongest electrostatics, whereas those that do not (D255, D249, and D274) are consistently weakest. As previously discussed, the positive residues do not fit the general electrostatic trend.

Figure 12.

Long-range electrostatic contributions of experimentally studied rectification and conductance residues in Kir2.1/IRK. The static field contributions of key determinants of rectification and conductance are shown in decreasing negative magnitude at three positions along the pore: (A) the cavity, (B) the membrane interface, and (C) the cytoplasmic domain. Neutralization of D172, E224, E299, D259, and corresponding double mutations has been shown in experiments to significantly affect rectification affinity while the other residues do not. The strongly positive residue R260 does not strongly influence rectification but affects conductance instead. Please see text for references.

How these different residues come together to confer the property of inward rectification is still unclear. The major blocking site for polyamines and Mg2+ is believed to be within the transmembrane pore, and negative charges lining this cavity clearly enhance the apparent affinity of block through electrostatic interactions (Lu and MacKinnon, 1994; Stanfield et al., 1994; Wible et al., 1994; Kurata et al., 2004). It is less obvious how charges in the cytoplasmic domain affect the process. Although the electrostatic field from these residues does propagate into the cavity region, it does not appear to do so with enough strength to alter the energetics of block at this location to a significant extent. The existence of two blocking sites has been suggested (Shin et al., 2005), and although the cytoplasmic domain itself could bind blockers, the pore is sufficiently wide to still allow ion flow. However, conformational changes in the cytoplasmic domain could occur upon binding and result in a new state that occludes the pore. In fact, the x-ray structures of the cytoplasmic domain have been determined in several different pore conformations (Nishida and MacKinnon, 2002; Kuo et al., 2003, 2005; Pegan et al., 2005; Nishida et al., 2007) that could be indicative of conformational flexibility in the physiological state as well. The membrane–cytoplasm interface represents a third potential blocking site. The electrostatic field in this region is affected by charges in both the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains (Fig. 12). This part of the channel may play a role in rectification as well as in the gating process (Pegan et al., 2005).

Summary

A comparative analysis of the electrostatics of five open-state models reveals that the extended mammalian Kir channel pore is a favorable pathway for cation interaction, demonstrating a diversity of electrostatic modulation in line with their functional differences. The cytoplasmic domain is a broad attractor for cations in all of the mammalian channels, whereas the cavity is a cation localization site only in the strong rectifiers. The present analysis indicates that residues along the long extended pore can exert considerable effects, up to 40 Å away. Therefore, electrostatics interactions act at unusually long-ranged distance in Kir channels, and could affect things like rectification affinity, even when far away from the binding site. The linker in between is particularly sensitive to the electrostatics in either domain and to external stimuli (e.g., PIP2 interactions and protonation state of K80 in Kir1.1/ROMK). Decomposition of the electrostatic contribution allows for identification of residues that are important for channel behavior and is a useful predictive tool for mutations in channels that have been less studied. These calculations lay down the groundwork for future studies in the multi-ion phenomenon of conduction and inward rectification block.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Declan Doyle for providing us with the KirBac1.1 open model. We acknowledge the help of Dr. Jose Faraldo-Gomez and Dr. Marta Murcia in the construction of the homology models, Dr. Vishwanath Jogini for his advice on the electrostatics calculations, Dr. Sergei Noskov and Dr. Diana Murray for the SPM4+ and PIP2 parameters, respectively, and Dr. Deniz Sezer for useful discussions.