Abstract

Human bestrophin-1 (hBest1), which is genetically linked to several kinds of retinopathy and macular degeneration in both humans and dogs, is the founding member of a family of Cl− ion channels that are activated by intracellular Ca2+. At present, the structures and mechanisms responsible for Ca2+ sensing remain unknown. Here, we have used a combination of molecular modeling, density functional–binding energy calculations, mutagenesis, and patch clamp to identify the regions of hBest1 involved in Ca2+ sensing. We identified a cluster of a five contiguous acidic amino acids in the C terminus immediately after the last transmembrane domain, followed by an EF hand and another regulatory domain that are essential for Ca2+ sensing by hBest1. The cluster of five amino acids (293–308) is crucial for normal channel gating by Ca2+ because all but two of the 35 mutations we made in this region rendered the channel incapable of being activated by Ca2+. Using homology models built on the crystal structure of calmodulin (CaM), an EF hand (EF1) was identified in hBest1. EF1 was predicted to bind Ca2+ with a slightly higher affinity than the third EF hand of CaM and lower affinity than the second EF hand of troponin C. As predicted by the model, the D312G mutation in the putative Ca2+-binding loop (312–323) reduced the apparent Ca2+ affinity by 20-fold. In addition, the D312G and D323N mutations abolished Ca2+-dependent rundown of the current. Furthermore, analysis of truncation mutants of hBest1 identified a domain adjacent to EF1 that is rich in acidic amino acids (350–390) that is required for Ca2+ activation and plays a role in current rundown. These experiments identify a region of hBest1 (312–323) that is involved in the gating of hBest1 by Ca2+ and suggest a model in which Ca2+ binding to EF1 activates the channel in a process that requires the acidic domain (293–308) and another regulatory domain (350–390). Many of the ∼100 disease-causing mutations in hBest1 are located in this region that we have implicated in Ca2+ sensing, suggesting that these mutations disrupt hBest1 channel gating by Ca2+.

INTRODUCTION

Mutations in human bestrophin-1 (hBest1) have been shown to be responsible for several retinopathies including Best vitelliform macular dystrophy (Petrukhin et al., 1998; Marquardt et al., 1998), adult-onset macular dystrophy (Seddon et al., 2001), autosomal dominant vitreochoidopathy (Yardley et al., 2004), autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy (Burgess et al., 2008), and canine multifocal retinopathy (Guziewicz et al., 2007). hBest1 is a Cl− ion channel that is activated by intracellular Ca2+ with a Kd of ∼150 nM (for review see Hartzell et al., 2008). The structures and mechanisms responsible for Ca2+ sensitivity, however, remain unknown. It seems likely that activation of the bestrophin channel is mediated by Ca2+ binding directly to the channel or to an accessory Ca2+-binding subunit, such as calmodulin (CaM), because channels are activated in excised patches containing hBest4 or dBest1 in the absence of ATP (Chien et al., 2006; Tsunenari et al., 2006). In this article, we focus on the potential role of a conserved region in the cytoplasmic C terminus immediately after the last predicted transmembrane domain in regulation of hBest1 by Ca2+.

The most common and well-understood kind of Ca2+-binding sites in proteins are EF hand motifs (for review see Nelson and Chazin, 1998; Lewit-Bentley and Rety, 2000; and Gifford et al., 2007). These are subdivided into the canonical EF hand as found in the CaM family and the pseudo–EF hand structures as found in the S100-like family. The Ca2+-binding loop of the canonical EF hand is formed primarily by side chain oxygens, whereas the pseudo–EF hand Ca2+-binding site is formed primarily by backbone carbonyl oxygens. In addition, there are other Ca2+-binding motifs, like the C2 domain, which have a less well-defined primary structure (Brose et al., 1995). The fact that Ca2+ can be coordinated by backbone carbonyl oxygens as well as by side chain oxygens means that at the present time prediction of Ca2+-binding sites from primary sequence data is challenging (Zhou et al., 2006). In any case, there are no obvious canonical EF hand motifs detected in hBest1 by motif-searching algorithms such as Pfam 22 (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/).

In trying to fathom the Ca2+-binding site of bestrophins, it has been noted that bestrophins exhibit a highly conserved region immediately after the last predicted transmembrane domain that contains a high concentration of acidic amino acids that might be involved in Ca2+ binding (Fig. 1) (Tsunenari et al., 2006; Hartzell et al., 2008). This region exhibits some similarity to the “Ca2+ bowl” of the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channel (Schreiber and Salkoff, 1997). The Ca2+ bowl was originally defined as a contiguous 28–amino acid sequence rich in negatively charged amino acids (glutamate and aspartate) and other amino acids with oxygen-containing side chains (asparagine or glutamine) that could coordinate Ca2+. There is compelling data that the Ca2+ bowl is involved in Ca2+ sensing by the BK channel. This region directly binds Ca2+ (Bian et al., 2001; Braun and Sy, 2001; Bao et al., 2004; Sheng et al., 2005), and replacing the five aspartic acids in the Ca2+ bowl with asparagines significantly reduces the regulation of the channel by Ca2+, especially at low Ca2+ concentrations (Schreiber and Salkoff, 1997; Bian et al., 2001; Xia et al., 2002). Furthermore, a transplanted Ca2+ bowl can confer Ca2+ sensitivity to a Ca2+-insensitive K+ channel (Schreiber et al., 1999). However, the Ca2+ bowl is only one of several loci involved in BK channel regulation by divalent cations. Each BK channel subunit contains two interacting regulator of conductance for K+ (RCK) domains (Qian et al., 2006; Yusifov et al., 2008). The Ca2+ bowl is located in RCK2, but several acidic amino acids in RCK1 contribute significantly to Ca2+ sensing (Shi and Cui, 2001; Zhang et al., 2001; Shi et al., 2002; Xia et al., 2002). The role of RCK domains in channel gating has been advanced by the crystallization of a bacterial Ca2+-activated K+ channel, MthK (Jiang et al., 2002; Qian et al., 2006; Lingle, 2007; Yusifov et al., 2008). In MthK, Ca2+ is thought to open the channel by binding to an octameric assembly of RCK domains. It is proposed that RCK1 and RCK2 interact via the αG-helix turn αF-helix to gate the channel. In addition to the RCK domains, it has also been suggested that there is a potential EF hand–like structure adjacent to the Ca2+ bowl, but mutation of key Ca2+-coordinating residues in the putative EF hand has small effect compared with mutations in the downstream acidic residues of the Ca2+ bowl (Braun and Sy, 2001; Sheng et al., 2005).

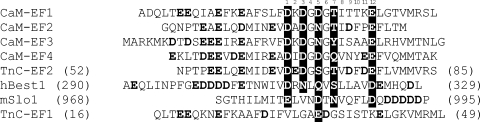

Figure 1.

Alignment of the BK channel (mslo1) with two acidic domains of hBest1. The alignment was done manually to emphasize the similarity in acidic amino acids. Acidic amino acids are bold.

The acidic domain of the bestrophins resembles the Ca2+ bowl in that it contains five contiguous acidic residues (EDDDD) (Fig. 1). This acidic region is adjacent to a region that we believe may resemble a Ca2+-binding EF hand. We have mutated amino acids in this region in an attempt to define the Ca2+-binding motif of hBest1. We find that this acidic cluster, the predicted EF hand, and another nearby acidic amino acid–rich domain are involved in Ca2+-dependent regulation of hBest1. Because many disease-causing mutations in hBest1 are located in this region, we conclude that this region is crucial for gating the channel by Ca2+.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs and Molecular Biology

hBest1 tagged with the myc epitope at the C terminus in pRK5 was obtained from J. Nathans (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) (Sun et al., 2002). Site-specific mutations were generated using PCR-based mutagenesis (Quickchanger; Agilent Technologies) (Qu et al., 2006a). All constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK cells were cultured as described previously (Yu et al., 2006). For electrophysiology experiments, low-passage HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected using Fugene-6 (Roche) with 1 μg hBest1 per 35-mm dish. Cells were also transfected with 0.2 μg pEGFP for fluorescent detection of transfected cells. Cotransfection of wild-type or mutant hBest1 with enhanced green fluorescent protein was performed at a ratio of 5:1. Transfected cells were plated at low density and investigated between 24 and 72 h after transfection.

Electrophysiology

Within 48–72 h after transfection, single cells identified by enhanced green fluorescent protein fluorescence were used for whole cell patch-clamp recording with an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier. The zero-Ca2+ pipette solution contained (in mM): 146 CsCl, 2 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 10 sucrose, and 8 HEPES, pH 7.3, adjusted with NMDG. The “high” Ca2+ pipette solution contained 5 mM (Ca2+)-EGTA, which supplied free Ca2+ of ∼11 μM. Solutions containing different free Ca2+ concentrations were obtained by mixing the zero-Ca2+ and high Ca2+ solutions (Tsien and Pozzan, 1989). The 200 μM of free Ca2+ solution contained (in mM): 146 CsCl, 1.89 CaCl2, 4.82 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 citric acid, pH. 7.3, with CsOH. Free Ca2+ concentrations were calculated with MaxChelator (Patton et al., 2004) and verified using Fura-2 or Fura-6F (Invitrogen). Osmolarity was adjusted with sucrose to 305 mOsm for all solutions. Electrode resistances were typically 2–3 MΩ in the bath solution. Voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV with a duration of 750 msec were given from a holding potential of 0 mV at 10-s intervals. Data analyses were done with Clampfit 9 (MDS Analytical Technologies) and Origin 7 software. The time constant of current rundown was determined by fitting the change in current amplitude with time to a single exponential, using data points after the current had reached a maximum. Because rundown may occur simultaneously with current activation, it is possible that the peak current in the absence of rundown would be larger than measured. We did not correct the peak currents for rundown because we do not know whether rundown begins immediately or whether there is some lag. All averaged data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance of differences (defined as P < 0.05) between groups was determined by one-way ANOVA or Student's t test as indicated.

Molecular Modeling

A three-dimensional homology model for hBest1 was built based on the coordinates of the third EF hand in human CaM (1cll.pdb) using Swiss-Model (Peitsch et al., 1995; Guex and Peitsch, 1997; Schwede et al., 2003). Amino acids 300–335 of hBest1 were first aligned manually with the four EF hands of CaM as shown in Fig. 4. The third EF hand of CaM (amino acids 81–116) was then used as the template in Swiss-Model to build the hBest1 homology model. The complex was minimized to convergence using Macromodel 9.5 (Schrödinger Inc.) with the OPLS2005 force field (Jorgensen and Tirado-Rives, 1988; Kaminski et al., 1994; Kaminski et al., 2001) and GB/SA water solvation (Still et al., 1990), while holding the backbone atoms of the helices fixed and all other atoms unrestrained. To model the D312G mutation in hBest1, the mutation was made in the initial Swiss-Model result and the structure was subjected to the same minimization protocol. The apo structures were obtained by removing Ca2+ from the initial Swiss-Model result and then minimizing as above. Uncorrected binding energies (EBIND) of Ca2+ to wild-type hBest1 and hBest1-D312G were determined by performing single point energy calculations (Eq. 1) using Jaguar 7.0 (Schrödinger Inc.) with Becke3LYP (Becke, 1993; Stephens et al., 1994), LACVP* (Hay and Wadt, 1985), and Poisson-Boltzmann water solvation (Tannor et al., 1994; Marten et al., 1996).

Figure 4.

Alignment of the four EF hands of CaM (1cll.pdb), the first and second EF hands of TnC (1dtl.pdb), the predicted EF hand of hBest1 C terminus (amino acids 290–329), and the Ca2+ bowl (amino acids 979–1,019) of the BK channel (Q08460). Amino acids in the Ca2+-binding loop are numbered 1–12. Amino acids that are known to coordinate Ca2+ in the crystal structure of CaM, TnC, and the predicted Ca2+-coordinating residues in first EF hand of hBest1 are white with a black background. Other negatively charged amino acids are bold. EF1 of TnC does not bind Ca2+.

To calculate the Ca2+ binding energy, single point energy calculations were made for (1) the minimized Ca2+–protein complex (ECOMPLEX), (2) the minimized Ca2+-free protein (EAPO), and (3) free Ca2+ (ECa).

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

These density-functional calculations were made tractable by removing residues outside the Ca2+-binding loop (hBest1 312–323) and capping the N and C termini with acetyl and N-methyl amide groups, respectively. Uncorrected binding energies were corrected by the counterpoise correction (ΔECP; Eq. 2) (Boys and Bernardi, 1970), determined by performing single-point energy calculations as above for the apo protein in the complex's geometry (EAPO|COMPLEX GEOMETRY), the complex with ghost orbitals on all atoms except Ca2+ (EGHOST,OTHER), and the complex with ghost orbitals only on Ca2+ (EGHOST,Ca). The corrected binding energy (ECORR) is then given by Eq. 3. To verify the suitability of this method, the same minimization and density functional calculations were done on the excised third EF hand of CaM containing Ca2+ (1cll.pdb, residues 81–116 for minimization, residues 93–104 for density functional calculations) and the excised first and second EF hands of cardiac troponin C (TnC; 1dtl.pdb, residues 16–51 and 52–85 for minimization, residues 28–40 and 65–76 for density functional calculations, respectively). For some calculations, an explicit water molecule was added to the model at the same position as the water located closest to Ca2+ in CaM. The structure was then minimized as described above.

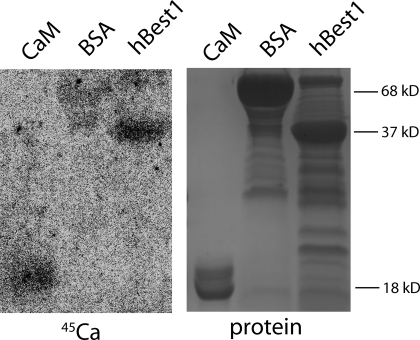

45Ca Overlay

An hBest1 fusion protein was constructed by amplifying the nucleotides encoding amino acids 289–585 of hBest1 cDNA by PCR with Pfu polymerase and subcloning the resulting PCR product into the XmaI-SacI sites of pET-52b (EMD). The resulting fusion protein contained a Strep-tag on the N-terminal end and a His(10) tag on the C terminus. 45Ca2+ overlay assays were done as described previously (Maruyama et al., 1984). After SDS-PAGE, proteins were electroblotted into a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was washed at room temperature three times for 20 min each in 30 ml wash buffer (60 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM imidazole, pH 6.8, treated with 1 g/liter Chelex-100 [Sigma-Aldrich] to remove contaminating divalent cations). The membrane was then incubated in 10 ml of wash buffer containing 0.2 μCi/ml 45Ca2+ (45Ca2+ concentration was 400 nM) for 20 min. The membrane was rinsed with 50% ethanol for 3 min, dried, and exposed to a phosphoscreen overnight. Bands were detected by the PhosphorImager system (GE Healthcare).

Cell Surface Biotinylation

The expression of hBest1 in the plasma membrane was examined with cell surface biotinylation as described previously (Yu et al., 2007). In brief, cells transfected with wild-type and mutant hBest1 and nontransfected cells were placed on ice, washed three times with PBS, and biotinylated with 0.5 mg/ml Sulfo-NHS-LC Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in PBS for 30 min. The cells were washed, collected, and suspended in lysis buffer (250 μl; 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM HEPES, pH7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% protease inhibitor cocktail III [EMD], and 10 μM PMSF per 100-mm dish). The extract was clarified at 10,000 g for 15 min. Biotinylated proteins were isolated by incubation of 200 μl of extract with 100 μl of streptavidin beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight with gentle agitation. The beads were collected and washed four times with 0.6 ml lysis buffer plus 200 mM NaCl. Bound biotinylated proteins were eluted, run on SDS-PAGE gels, and probed with anti-myc and anti-GAPDH antibodies, followed by secondary anti–mouse IgG. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL kit; GE Healthcare).

RESULTS

A Potential Ca2+ Sensor in the C Terminus of hBest1

The C terminus of hBest1 shares some similarities to the Ca2+ bowl region of the BK channel (mSlo1) known to be involved in Ca2+ sensing. In Fig. 1, the amino acid sequence of the Ca2+ bowl of the BK channel is aligned with two segments of the C terminus of hBest1 (amino acids 288–329 and 369–394). Both hBest1 segments have similarity to the BK Ca2+ bowl in that they contain five contiguous acidic amino acids (positions 300–304 and 380–384) flanked by several additional acidic residues. We have previously referred to the first group of acidic amino acids as the “acidic cluster” (Hartzell et al., 2008), and this region was proposed as a potential Ca2+-binding site by Tsunenari et al., (2006). Here, we have made point mutations in 20 amino acids between 293 and 323, with a focus on the acidic cluster and the region immediately after it (Fig. 2). Each amino acid was mutated to at least one other amino acid. All mutations except at positions 298, 307, 312, 316, 320, and 323 produced channels that were essentially nonfunctional. The acidic domain (293–308) in particular was very sensitive to mutation. Only two (F298W and T307S) of the 35 mutations (not all are depicted) in this region produced functional channels (Fig. 2 A). The high sensitivity of this region to mutation suggests that, like the Ca2+ bowl in the BK channel, the acidic cluster in hBest1 is extremely important in channel gating. To determine whether mutations in the acidic cluster altered protein expression or trafficking, we measured the amount of protein on the plasma membrane by cell surface biotinylation (Fig. 2 B). These data show that, at least qualitatively, mutations in the acidic domain did not significantly alter protein expression or trafficking.

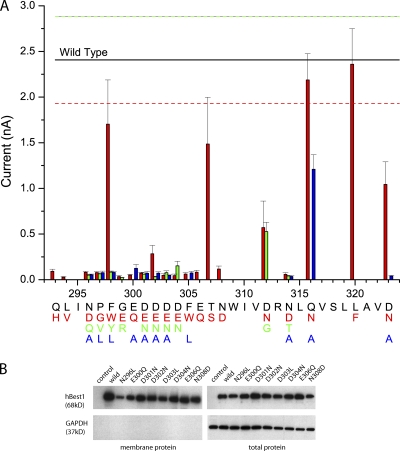

Figure 2.

Effects of mutations in the hBest1 C terminus on channel function. (A) Current amplitudes of point mutants in the C-terminal acidic region (amino acids 293–308) and the putative EF hand loop (amino acids 312–323). Each amino acid (in black) and its position in the C terminus are indicated along the axis. The corresponding mutations are colored red, green, and blue. Each data point represents four to nine cells. The solid line indicates the average current amplitude of wild type (n = 8), and the dashed lines represent the standard error. (B) Expression of hBest1 mutants in the plasma membrane of HEK cells. Wild-type, N296L, E300Q, D301N, D302N, D303L, D304N, E306Q, and N308D mutant-transfected and nontransfected cells were exposed to membrane-impermeable Sulfo-NHS-LC biotin. Biotinylated membrane proteins (20 μl; left) purified with streptavidin resin and total proteins (5 μl; right) were probed with antibodies to the myc tag on hBest1 (68-kD band; top) and with antibodies to intracellular protein GAPDH (37-kD band; bottom).

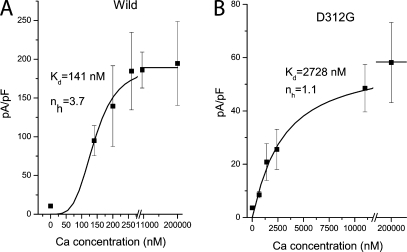

Mutations at positions 312, 316, 320, and 323 produced functional channels, and several mutations at these positions produced currents that differed in interesting ways from wild-type currents, as described below. In particular, we noticed that substitution of D312 with N or G reduced the EC50 for channel activation by intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 3). Wild-type hBest1 was activated by Ca2+ with an EC50 of 141 nM, whereas the D312G mutant was ∼20-fold less sensitive, with an EC50 of 2.7 μM. Furthermore, the Hill coefficient for Ca2+ binding was reduced from 3.7 to 1.1. This suggests that Ca2+ binding to the wild-type channel occurs cooperatively, possibly as a consequence of the putative tetrameric nature of the channel (Sun et al., 2002). In contrast, binding of Ca2+ to the D312G mutant channel was not appreciably cooperative.

Figure 3.

D312G mutant has reduced Ca2+ sensitivity. The current densities at +100 mV from wild-type (A) and D312G mutant (B) are plotted versus free [Ca2+]i. The plots were fitted to the Hill equation (Kd's were 141 and 2,728 nM for wild-type and D312G mutant, respectively; nH's were 3.7 and 1.1 for wild-type and D312G mutant, respectively). Each data point represents five to nine cells.

In examining the sequence surrounding D312, we noticed a pattern of amino acids that suggested the possibility that D312 was located in a non-canonical EF hand structure. In Fig. 4, hBest1 amino acids 290–329 are aligned with the four EF hands of CaM, EF hands 1 and 2 of cardiac TnC, and the proposed EF hand of the BK channel. In the alignment, the amino acids in the Ca2+-binding loops of CaM are numbered 1–12. The amino acids that are known from the CaM crystal structure (Chattopadhyaya et al., 1992) to coordinate Ca2+ have a red background. Amino acids at positions 1, 3, 5, and 12 coordinate Ca2+ directly via carboxylate or carbonyl oxygens of their side chains, whereas the amino acid at position 7 (T, Y, or Q) coordinates Ca2+ by its backbone carbonyl oxygen. The first EF hand of cardiac TnC lacks oxygen-containing amino acid side chains at four of the five positions and is known experimentally not to bind Ca2+ (Nelson and Chazin, 1998). The sequence in hBest1 that resembles an EF hand Ca2+-binding loop has amino acids with oxygen-containing side chains at positions corresponding to 1, 3, 5, and 12 and has a serine at position 7, which is similar to the corresponding threonine of CaM loops 1 and 2. In addition, the conserved acidic residues in CaM at positions −6 and −9 are also acidic in hBest1.

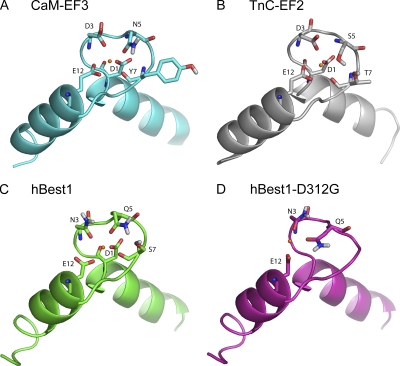

A Model of Ca2+ Binding to the hBest1 EF Hand

To determine whether this region was theoretically capable of binding Ca2+, a homology model of hBest1 residues 300–335 was built based on the third EF hand of the CaM x-ray crystal structure using Swiss-Model. The structure included Ca2+ and was refined by minimization with MACROMODEL. As shown in Fig. 5, the hBest1 model closely resembles the EF hand of CaM. In CaM, Ca2+ is coordinated by carboxyl oxygens from D1, D3, and E12, and by carbonyl oxygens from N5 and Y7. In the hBest1 model, Ca2+ is coordinated by carboxyl oxygens from D1 and D12 and by carbonyl oxygens from N3, Q5, and S7. Thus, one carboxyl interaction is traded for a carbonyl interaction in hBest1 compared with CaM.

Figure 5.

Models of Ca2+-binding loops. Models were generated as described in Materials and methods. The models are shown as ribbon diagrams with Ca2+-coordinating amino acids shown as tubes. Amino acids are numbered according to the positions in the Ca2+-binding loop as in Fig. 3. (A) The third EF hand of CaM. (B) The second EF hand of TnC. (C) The predicted EF hand of hBest1. (D) The predicted EF hand of hBest1 with the D312G mutation. Model predicts that calcium loses interaction with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of S7 in addition to loss of interaction with the carboxylate oxygens of D1/D312.

To estimate the Ca2+-binding affinity of the hBest1 model, we compared the calculated Ca2+-binding affinities of the hBest1 model to the third EF hand of CaM, as well as the first and second EF hands of TnC (Table I and Fig. 5). Density-functional single-point energy calculations were done on the minimized Ca2+–protein complexes, the Ca2+-free proteins, and free Ca2+. The resulting corrected binding energy of Ca2+ to CaM was −4.9 kcal/mol. This calculated result is very close to the experimentally determined value of ∼−7 kcal/mol to single EF hands (3 or 4) in CaM (VanScyoc et al., 2006). We also calculated the binding energy with an explicit water added from the crystal structure. This calculation provided a very similar binding energy of −5.5 kcal/mol. For the hBest1 EF hand, the corrected binding energy for Ca2+ binding was −6.0 kcal/mol without an explicit water and −7.6 kcal/mol with an explicit water added from CaM.

TABLE I.

Calculated Binding Energies of EF Hands

| Without explicit water (kcal/mol) |

With explicit water (kcal/mol) |

|

|---|---|---|

| CaM EF3 | −4.9 | −5.5 |

| TnC EF2 | −19.0 | −26.0 |

| hBest1 | −6.0 | −7.6 |

| hBest1 D312G | +6.6 | −2.4 |

| TnC EF1 | +37.2 | +15.0 |

Binding energies were calculated for EF hands from CaM and TnC, proteins with solved x-ray structures, and compared to the homology-modeled hBest1 and mutant hBest1 EF hands. Calculations were performed using implicit Poisson-Boltzmann hydration with and without an added explicit water ligand for bound Ca2+ as described in Materials and methods. EF1 or TnC is known not to bind Ca.

Our calculated result is closer to experimentally determined values than other recent predictions (Lepsik and Field, 2007). The difference is likely explained by different methods for calculating the effects of water solvation: we used Poisson-Boltzmann water solvation (Tannor et al., 1994; Marten et al., 1996), whereas Lepsik and Field used COSMO (Lepsik and Field, 2007). Preliminary calculations of Ca2+-binding energy for the third CaM EF hand using our methodology without solvation gave a binding energy of ∼400 kcal/mol, which is similar to the value of 200–300 kcal/mol calculated by Lepsik and Field (2007). This suggests that our solvation method may more fully account for the electrostatic screening effect of water.

To test our method further, we calculated the binding affinities of the first and second EF hands of TnC. The second EF hand of TnC is known to bind Ca2+, whereas the first EF hand does not. The corrected binding energies for the TnC structures are −19.0 kcal/mol for the second EF hand and 37.2 kcal/mol for the first EF hand, correctly indicating that Ca2+ binding is highly favorable for the second EF hand, but disfavored for the first EF hand.

These results suggest that hBest1 binds Ca2+ with an affinity similar to CaM, despite having one interaction with a carbonyl oxygen instead of a carboxyl oxygen as seen in CaM. Small differences in binding energy are probably not meaningful because of certain assumptions we used in model building. Most notably, we assumed that the conformation of the E- and F-helices in hBest1 were similar to those in CaM and constrained these residues during minimization. Nonetheless, the models do provide a structural context for a likely site of Ca2 binding in hBest1 and in general are consistent with experimental results.

To determine whether mutations in the putative EF hand loop of hBest1 had an effect on Ca2+ affinity, a structural model of the hBest1 EF hand with the D312G mutation was developed from the wild-type model and refined as described above (Fig. 5). This mutation would be expected to reduce the binding affinity of hBest1 for Ca2+ based on the mutation removing the D1 carboxylate interaction with Ca2+. The effect of the D312G mutation on Ca2+-binding energy was predicted using the same density functional method as above, resulting in a corrected binding energy of 6.6 kcal/mol, indicating that Ca2+ binding is unfavorable, compared with −6.0 kcal/mol for wild-type hBest1. When the explicit water was added to this model, the binding energy was estimated to be −2.4 kcal/mol. These predictions are consistent with D312 being located in an EF hand structure that is involved in coordinating Ca2+.

Ca2+ Binding to hBest1 C Terminus

To determine whether the C terminus of hBest1 actually binds Ca2+, we performed a 45Ca2+ overlay using an hBest1 C-terminal fusion protein (Fig. 6). The same molar amounts of hBest1 C terminus, CaM, and bovine serum albumin were run on SDS-PAGE and blotted to nitrocellulose. The blot was exposed to 45Ca2+ and washed briefly. The hBest1 C-terminal fragment and CaM bound a qualitatively similar amount of 45Ca2+, whereas bovine serum albumin did not bind a detectable amount of 45Ca2+.

Figure 6.

Direct binding of 45Ca2+ by hBest1 C terminus. Equimolar amounts of CaM (7.1 μg), BSA (29.4 μg), and hBest1 (16.5 μg) were loaded onto the gel. Autoradiogram of the blot after 45Ca overlay (left) showed hBest1 (right lane) had a similar amount of Ca2+ binding to CaM (left lane). BSA (middle lane) was used for nonspecific binding of Ca2+. Ponceau staining of the proteins is shown on the right.

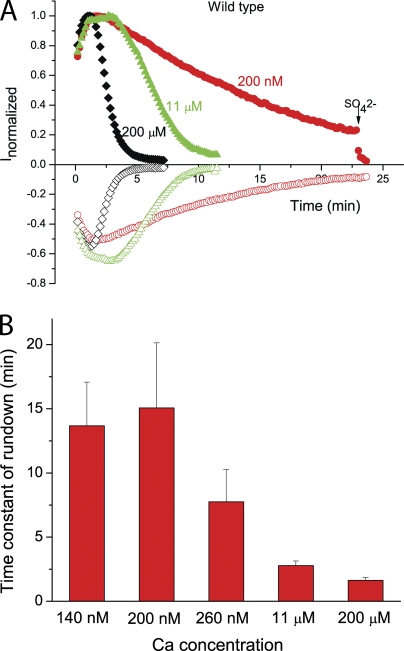

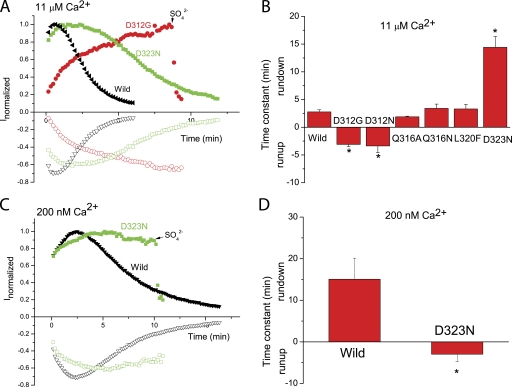

Rundown of hBest1 Current

The D312G mutation not only reduced the Ca2+ sensitivity of the channel, but it also affected how the current ran down with time after initiating whole cell recording. Fig. 7 describes the rundown of the wild-type current, and Fig. 8 describes the effect of the D312 mutations on rundown.

Figure 7.

Ca2+-dependent rundown of wild-type hBest1. (A) Time course of wild-type hBest1 current recorded in the presence of 200 μM Ca2+ (black square), 11 μM Ca2+ (green triangle), and 200 nM Ca2+ (red circle) in the patch pipette. Voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV were given from a holding potential of 0 mV at 10-s intervals. The currents at +100 mV (solid) and −100 mV (open) were normalized to the peak current. (B) Effects of different concentrations of Ca2+ on the channel rundown of wild-type hBest1. The rundown was measured by fitting the rundown after the current had reached a peak to a single exponential. Each data point represents five to eight cells.

Figure 8.

Effects of mutations in the Ca2+-binding loop of the first EF hand reduced channel rundown. (A and C) Time course of typical currents of wild-type (black triangles), D312G mutant (red circles), and D323N mutant (green squares), activated by 11 μM Ca2+ (A and B) and by 200 nM Ca2+ (C and D). Voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV were given from a holding potential of 0 mV at 10-s intervals. Currents at +100 mV (solid) and −100 mV (open) were normalized to the peak currents. (B and D) Effects of mutations in the EF hand loop on the channel rundown. The rundown was measured by fitting the rundown after the current had reached a peak to a single exponential. When currents did not run down, but rather ran up, the increase was fitted to an exponential and the τ was expressed as a negative number. n = 5–8; *, P < 0.05 versus wild type by one-way ANOVA.

The wild-type current typically increased for the first minute after patch break and then ran down. The rate of rundown was dependent on intracellular Ca2+. As shown in Fig. 7 A, with ∼200 nM of free Ca2+ in the patch pipet, the current increased for the first 2 min after breaking the patch and then ran down with a half-time of ∼10 min. In contrast, with 200 μM Ca2+ in the patch pipet, rundown was complete within 2 min (Fig. 7, A and B). To quantify rundown, we fit the time course of rundown to a single exponential, starting after the current had reached its peak amplitude (Fig. 7 B).

Mutations in the EF hand Ca2+-binding loop affected rundown significantly (Fig. 8). Of the mutations we tested, the ones that produced the greatest effects were mutations at positions 312 and 323, which correspond to positions 1 and 12 of the CaM EF-loop (Fig. 8 B). For D323N, τ = ∼14 min compared with <3 min for wild type. Rundown was completely absent for the D312G and D312N mutations. In fact, these currents ran up with time. For example, the D312G current (Fig. 8 A) started at a low level (consistent with its lower Ca2+ affinity) and then increased over the next 10 min, presumably as a result of Ca2+ diffusion into the cell from the patch pipet. The time course of current run-up is indicated as a negative τ in the bar graphs. The effect was also apparent for D323N at 200 nM Ca2+ (Fig. 8, C and D). The Q316A, Q316N, and L320F mutations had rundown similar to wild type.

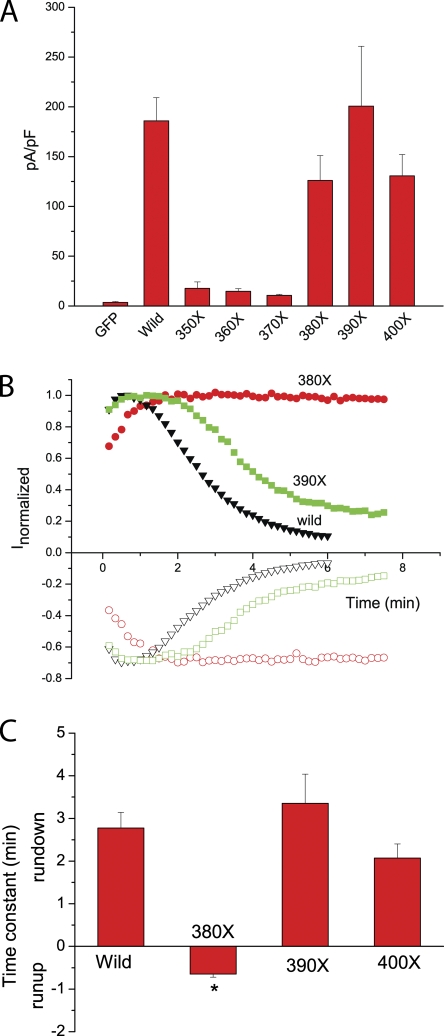

A Second Domain Contributes to Ca2+-dependent Channel Gating

As noted above (Fig. 1), there is a second segment (amino acids 357–391) in the C terminus of hBest1 that is rich in acidic amino acids. EF hands almost always exist in pairs (Nelson and Chazin, 1998; Lewit-Bentley and Rety, 2000), but homology models of this region to CaM EF hands did not predict favorable Ca2+ binding. Nevertheless, to determine whether this region contributes to Ca2+-dependent channel gating, we made truncation mutants every 10 amino acids from position 350 to 400 (Fig. 9). Truncation of the C terminus at position 390 or 400 produced currents that were essentially like wild type (Fig. 9 A). In contrast, truncation of the C-terminus at position 350, 360, or 370 resulted in channels that were essentially nonfunctional (Fig. 9 A), and truncation at amino acid 380 abolished rundown (Fig. 9, B and C). These data suggest that the region between positions 350 and 390 is important in channel gating.

Figure 9.

Effects of truncation mutants on channel activation and rundown. (A) Mean current density at +100 mV. The 350X, 360X, and 370X mutants had the similar current density as GFP alone, whereas the 380X, 390X, and 400X mutants showed similar current density as the wild type. (B) Time course of currents of wild-type (black triangles), 380X mutant (red circles), and 390X mutant (green squares). 380X mutant abolished rundown. *, P < 0.05 versus wild-type and 390X and 400X mutants. (C) Time constant of rundown or run-up of currents. (n = 6–8). The 350X, 360X, 370X, 380X, 390X, and 400X mutants were made by introducing stop codons at amino acids 350, 360, 370, 380, 390, and 400, respectively.

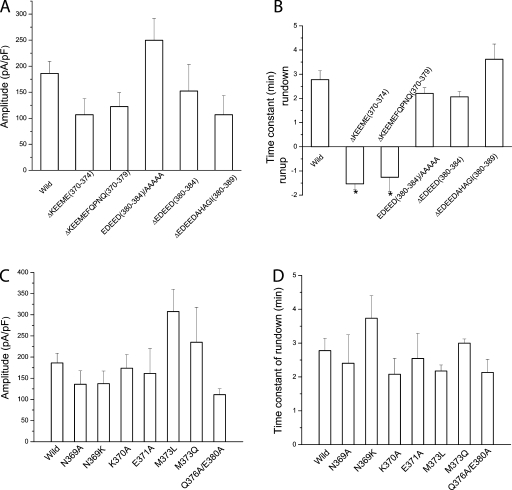

To narrow down the amino acids involved in rundown, we made deletions and point mutations in this region (Fig. 10). Because truncation at amino acid 380 abolished rundown, whereas truncation at amino acid 390 behaved like wild type, we expected that residues involved in rundown would be located between positions 380 and 390. However, deletion of amino acids 380–384 (EDEED) or 380–389 (EDEEDAHAG) or substitution of amino acids 380–384 (EDEED) with alanines (AAAAA) had no significant effect on current rundown or amplitude (Fig. 10, A and B). In contrast, deletion of amino acids 370–374 (KEEME) or 370–379 (KEEMEFQPNQ) abolished rundown (Fig. 10, A and B), suggesting that amino acids 370–374 are key in regulating rundown. Rundown was not significantly affected by point mutations in selected amino acids (N369, K370, E371, M373, Q376, and E380; Fig. 10, C and D), suggesting that the function of this region may depend on several interacting amino acids.

Figure 10.

Effects of deletions and substitutions of amino acids in the second acidic domain of hBest1. (A and C) Current amplitudes. (B and D) Time constant of rundown or run-up. (A and B) Deletions and substitutions of groups of amino acids between 370 and 390. (C and D) Point mutations in selected amino acids from 369 to 380.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that the hBest1 C terminus binds Ca2+ and thus provides additional evidence that hBest1 is activated directly by Ca2+ binding to the channel (Chien et al., 2006; Tsunenari et al., 2006). These experiments demonstrate that at least three different regions collaborate in gating hBest1 by Ca2+: an EF hand–like domain (EF1), the first acidic cluster located in the cytosolic C terminus adjacent to the last transmembrane domain, and the second acidic region C terminal to EF1. Gating of hBest1 by Ca2+ can be explained entirely by this region because hBest1 lacking the C terminus after amino acid 390 behaves identically to wild type, suggesting that no other Ca2+-binding site in the C terminus is required for channel function.

An EF Hand (EF1) Is a Ca2+-binding Site

We conclude that EF1 is a key part of the Ca2+-binding site in hBest1 because mutation of amino acids in the predicted Ca2+-binding loop of EF1 drastically alters the Ca2+ sensitivity of the channel as well as Ca2+-dependent rundown. The decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity produced by these mutations is predicted by density-functional binding energy calculations of the Ca2+-binding loop.

hBest1 EF1 shares important characteristics with canonical EF hand Ca2+-binding loops. The canonical EF hand consists of 29 contiguous amino acids containing helix-E, a loop around the Ca2+ ion, and helix-F. The Ca2+-binding loop is formed by side chain oxygens from loop residues 1, 3, 5, and 12 and backbone carbonyl oxygens from residue 7 (Fig. 4 and 5). Residue 1 in the Ca2+-binding loop is an invariant asparate, and the carboxylate group of the side chain plays an essential role in coordinating Ca2+. The mutations we made in the corresponding amino acid in hBest1 (D312N and D312G) significantly altered the Ca2+ sensitivity of the channel. Residue 12 provides two oxygen ligands, usually from glutamate, but sometimes aspartate (Gifford et al., 2007), as it is in hBest1. Replacing the aspartate in the 12th position of hBest1 EF1 with alanine completely abolished channel activation by Ca2+. The more conservative D323N mutation significantly reduced channel rundown, suggesting an important role of this position in Ca2+-mediated channel function. Mutations at position 3 in the hBest1 EF1 loop (N314D, N314T, and N314A) resulted in nonfunctional channels, suggesting that this position is also critical in Ca2+ coordination. Position 5 in many EF hands is glycine and may be important in allowing flexibility in the loop so that other residues can adopt energetically favorable orientations for coordinating Ca2+. In hBest1, position 5 is not a glycine, but rather glutamine. Mutations at this position (Q316A and Q316N) had no significant effects on channel activation or rundown compared with wild type. Residue 7 coordinates Ca2+ via a backbone carbonyl oxygen in both canonical EF hands and hBest1 EF1. In most EF hands, the Ca2+ oxygen distances are between 2 and 3 Å and there are between five and eight oxygens per Ca2+ (Pidcock and Moore, 2001; Yang et al., 2002). In this regard, our hBest1 model fits the requirements for a Ca2+-binding loop.

The Acidic Clusters

Mutation of the first acidic cluster of amino acids in hBest1 results in channels that cannot be activated by Ca2+. The nonfunction of these channels is not explained simply by expression or trafficking defects, suggesting that this region of the protein is important either in sensing or responding to Ca2+. The location of this region immediately after the last predicted transmembrane domain suggests that it may be important in channel gating. Amino acids flanking the acidic cluster are also very important in channel gating because mutations of most of the amino acids between position 293 and 306 produce nonfunctional channels.

Our data shows that there is a second acidic region that is important in Ca2+-dependent channel rundown. This region is located between amino acids 370 and 390. In this region, there are eight acidic amino acids and three additional amino acids with oxygen-containing side chains. Although it was possible to forcibly align and homology-model this region as an EF hand, it seems unlikely that this region binds Ca2+ for several reasons. First, density-functional calculations predicted that Ca2+ binding to this region was not favorable. Furthermore, deletion or neutralization of potential Ca2+-coordinating amino acids (amino acids with oxygen-containing side chains: 380EDEED384, N369A, E371, Q376, and E380) had no effect on Ca2+ sensitivity or rundown of the channel. However, it is tempting to speculate that this region may be a nonfunctional EF hand. EF hands are often found as pairs and form a four-helix bundle that exhibits cooperativity in Ca2+ binding (Lewit-Bentley and Rety, 2000). In some proteins, such as TnC, one of the paired EF hands is incapable of binding Ca2+, but binding of a single Ca2+ ion is sufficient to activate the protein. Proteins having an unpaired EF hand frequently dimerize, resulting in intermolecular coupling of the EF hands (Yap et al., 1999; Ravulapalli et al., 2005). The high cooperativity (nH ∼4) of Ca2+ binding that we observe could be a consequence of multimerization of bestrophins, which have been suggested to exist as dimers or tetramers (Sun et al., 2002; Stanton et al., 2006). The observation that nH of Ca2+ activation decreases from 4 to ∼1 with the D312G mutation supports the idea that EF1 normally binds Ca2+ in a cooperative fashion.

Mechanism of Channel Activation and Rundown

Ca2+-activated hBest1 current shows an activation phase and rundown phase, suggesting that hBest1 channels have at least three states: closed (no Ca2+ bound), open (Ca2+ bound), and inactivated (rundown). hBest1 current is activated by Ca2+ with a very high affinity (EC50 = 141 nM), showing that the closed state has a high affinity for Ca2+. Binding of Ca2+ induces a conformational change to an open state, but in addition somehow regulates the acidic domain between amino acids 370–390 to produce channel rundown. We have little insight into the actual mechanisms of rundown, but interestingly, amino acids 354–362 of hBest1, located between EF1 and the second acidic domain, correspond to the region we have previously identified as a regulatory domain in Best3. This region contains a serine that is a predicted PKA/PKC phosphorylation site (Qu et al., 2006b, 2007). This domain may also participate in channel regulation by Ca2+, maybe by a process involving phosphorylation.

Molecular modeling shows that the D312G mutant requires higher energy to bind Ca2+. Thus, binding of Ca2+ may not induce a full open-state channel and rundown may be thwarted. The smaller current amplitude of D312G mutant supports this possibility. Such a partially activated conformation has been reported in the EF hand of myosin light chain (PDB code, 1WDC) (Houdusse et al., 1996; Houdusse and Cohen, 1996; Nelson and Chazin, 1998). The channel could be locked in this state due to insufficient energy to switch into the inactivated state.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM60448 and EY014852.

Edward N. Pugh Jr. served as editor.

Abbreviations used in this paper: BK, large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+; CaM, calmodulin; hBest1, human bestrophin-1; RCK, regulator of conductance for K+; TnC, Troponin C.

References

- Bao, L., C. Kaldany, E.C. Holmstrand, and D.H. Cox. 2004. Mapping the BKCa channel's “Ca2+ bowl”: side chains essential for Ca2+ sensing. J. Gen. Physiol. 123:475–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke, A.D. 1993. Density-functional thermochemistry. 3. The role of exact exchange. J. Phys. Chem. 98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, S., I. Favre, and E. Moczydlowski. 2001. Ca2+-binding activity of a COOH-terminal fragment of the Drosophila BK channel involved in Ca2+-dependent activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:4776–4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boys, S.F., and F. Bernardi. 1970. Calculation of small molecular interactions by differences of separate total energies-some procedures with reduced errors. Mol. Phys. 19:553–566. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, A.P., and L. Sy. 2001. Contribution of potential EF hand motifs to the calcium-dependent gating of a mouse brain large conductance, calcium-sensitive K+ channel. J. Physiol. 533:681–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose, N., K. Hofmann, Y. Hata, and T.C. Sudhof. 1995. Mammalian homologues of Caenorhabditis elegans unc-13 gene define novel family of C(2)-domain proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 270:25273–25280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, R., I.D. Millar, B.P. Leroy, J.E. Urquhart, I.M. Fearon, B.E. De, P.D. Brown, A.G. Robson, G.A. Wright, P. Kestelyn, et al. 2008. Biallelic mutation of BEST1 causes a distinct retinopathy in humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82:19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyaya, R., W.E. Meador, A.R. Means, and F.A. Quiocho. 1992. Calmodulin structure refined at 1.7 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 228:1177–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien, L.T., Z.R. Zhang, and H.C. Hartzell. 2006. Single Cl− channels activated by Ca2+ in Drosophila S2 cells are mediated by bestrophins. J. Gen. Physiol. 128:247–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, J.L., M.P. Walsh, and H.J. Vogel. 2007. Structures and metal-ion-binding properties of the Ca2+-binding helix-loop-helix EF-hand motifs. Biochem. J. 405:199–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex, N., and M.C. Peitsch. 1997. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 18:2714–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guziewicz, K.E., B. Zangerl, S.J. Lindauer, R.F. Mullins, L.S. Sandmeyer, B.H. Grahn, E.M. Stone, G.M. Acland, and G.D. Aguirre. 2007. Bestrophin gene mutations cause canine multifocal retinopathy: a novel animal model for best disease. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48:1959–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell, H.C., Z. Qu, K. Yu, Q. Xiao, and L.T. Chien. 2008. Molecular physiology of bestrophins: multifunctional membrane proteins linked to best disease and other retinopathies. Physiol. Rev. 88:639–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay, P.J., and W.R. Wadt. 1985. Ab-initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations -potentials for K to Au including outermost pore orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 82:299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Houdusse, A., and C. Cohen. 1996. Structure of the regulatory domain of scallop myosin at 2 A resolution: implications for regulation. Structure. 4:21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdusse, A., M. Silver, and C. Cohen. 1996. A model of Ca(2+)-free calmodulin binding to unconventional myosins reveals how calmodulin acts as a regulatory switch. Structure. 4:1475–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., A. Lee, J. Chen, M. Cadene, B.T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 2002. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature. 417:515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, W.L., and J. Tirado-Rives. 1988. The OPLS potential functions for proteins-energy minimizations for crystals of cyclic-peptides and crambin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 110:1657–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski, G., E.M. Duffy, T. Matsui, and W.L. Jorgensen. 1994. Free energies of hydration and pure liquid properties of hydrocarbons from the OPLS all-atom model. J. Phys. Chem. 98:13077–13082. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski, G., R.A. Friesner, J. Tirado-Rives, and W.L. Jorgensen. 2001. Evaluation and reparametrization of the OPLS-AA force field for proteins via comparison with accurate quantum chemical calculations on peptides. J. Phys. Chem. 105:6474–6487. [Google Scholar]

- Lepsik, M., and M.J. Field. 2007. Binding of calcium and other metal ions to the EF-hand loops of calmodulin studied by quantum chemical calculations and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 111:10012–10022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewit-Bentley, A., and S. Rety. 2000. EF-hand calcium-binding proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10:637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingle, C.J. 2007. Gating rings formed by RCK domains: keys to gate opening. J. Gen. Physiol. 129:101–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, A., H. Stohr, L.A. Passmore, F. Kramer, A. Rivera, and B.H. Weber. 1998. Mutations in a novel gene, VMD2, encoding a protein of unknown properties cause juvenile-onset vitelliform macular dystrophy (Best's disease). Hum. Mol. Genet. 7:1517–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marten, B., K. Kim, C. Cortis, R.A. Friesner, and R. Murphy. 1996. New model for calculation of solvation free energies: correction of self-consistent reaction field. J. Phys. Chem. 100:11775–11788. [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama, K., T. Mikawa, and S. Ebashi. 1984. Detection of calcium binding proteins by 45Ca autoradiography on nitrocellulose membrane after sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis. J. Biochem. (Tokyo). 95:511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, M.R., and W.J. Chazin. 1998. Structures of EF-hand Ca(2+)-binding proteins: diversity in the organization, packing and response to Ca2+ binding. Biometals. 11:297–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, C., S. Thompson, and D. Epel. 2004. Some precautions in using chelators to buffer metals in biological solutions. Cell Calcium. 35:427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peitsch, M.C., T.N. Wells, D.R. Stampf, and J.L. Sussman. 1995. The Swiss-3DImage collection and PDB-Browser on the World-Wide Web. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20:82–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrukhin, K., M.J. Koisti, B. Bakall, W. Li, G. Xie, T. Marknell, O. Sandgren, K. Forsman, G. Holmgren, S. Andreasson, et al. 1998. Identification of the gene responsible for Best macular dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 19:241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidcock, E., and G.R. Moore. 2001. Structural characteristics of protein binding sites for calcium and lanthanide ions. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 6:479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian, X., X. Niu, and K.L. Magleby. 2006. Intra- and intersubunit cooperativity in activation of BK channels by Ca2+. J. Gen. Physiol. 128:389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Z., L.T. Chien, Y. Cui, and H.C. Hartzell. 2006. a. The anion-selective pore of the bestrophins, a family of chloride channels associated with retinal degeneration. J. Neurosci. 26:5411–5419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Z., Y. Cui, and C. Hartzell. 2006. b. A short motif in the C-terminus of mouse bestrophin 4 inhibits its activation as a Cl channel. FEBS Lett. 580:2141–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Z., K. Yu, Y. Cui, C. Ying, and C. Hartzell. 2007. Activation of bestrophin Cl channels is regulated by C-terminal domains. J. Biol. Chem. 282:17460–17467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravulapalli, R., B.G. Diaz, R.L. Campbell, and P.L. Davies. 2005. Homodimerization of calpain 3 penta-EF-hand domain. Biochem. J. 388:585–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, M., and L. Salkoff. 1997. A novel calcium-sensing domain in the BK channel. Biophys. J. 73:1355–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, M., A. Yuan, and L. Salkoff. 1999. Transplantable sites confer calcium sensitivity to BK channels. Nat. Neurosci. 2:416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwede, T., J. Kopp, N. Guex, and M.C. Peitsch. 2003. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3381–3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon, J.M., M.A. Afshari, S. Sharma, P.S. Bernstein, S. Chong, A. Hutchinson, K. Petrukhin, and R. Allikmets. 2001. Assessment of mutations in the best macular dystrophy (VMD2) gene in patients with adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy, age-related maculopathy, and bull's-eye maculopathy. Ophthalmology. 108:2060–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, J.Z., A. Weljie, L. Sy, S. Ling, H.J. Vogel, and A.P. Braun. 2005. Homology modeling identifies C-terminal residues that contribute to the Ca2+ sensitivity of a BKCa channel. Biophys. J. 89:3079–3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J., and J. Cui. 2001. Intracellular Mg2+ enhances the function of BK-type Ca2+-activated K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 118:589–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J., G. Krishnamoorthy, Y. Yang, L. Hu, N. Chaturvedi, D. Harilal, J. Qin, and J. Cui. 2002. Mechanism of magnesium activation of calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature. 418:876–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, J.B., A.F. Goldberg, G. Hoppe, L.Y. Marmorstein, and A.D. Marmorstein. 2006. Hydrodynamic properties of porcine bestrophin-1 in Triton X-100. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1758:241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, P.J., F.J. Devlin, C.F. Chabalowski, and M.J. Frisch. 1994. Ab-initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular-dichroism spectra using density-functional force-fields. J. Phys. Chem. 98:11623–11627. [Google Scholar]

- Still, W.C., A. Tempczyk, R.C. Hawley, and T. Hendrickson. 1990. Semianalytical treatment of solvation for molecular mechanics and dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112:6127–6129. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H., T. Tsunenari, K.-W. Yau, and J. Nathans. 2002. The vitelliform macular dystrophy protein defines a new family of chloride channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:4008–4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannor, D.J., B. Marten, R. Murphy, R.A. Friesner, D. Sitkoff, A. Nicholls, M. Ringnalda, W.A. Goddard, and B. Honig. 1994. Accurate first principles calculation of molecular charge-distributions and solvation energies from ab-initio quantum mechanics and continuum dielectric theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116:11875–11882. [Google Scholar]

- Tsien, R.Y., and T. Pozzan. 1989. Measurements of cytosolic free Ca2+ with Quin-2. Methods Enzymol. 172:230–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunenari, T., J. Nathans, and K.W. Yau. 2006. Ca2+-activated Cl− current from human bestrophin-4 in excised membrane patches. J. Gen. Physiol. 127:749–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanScyoc, W.S., R.A. Newman, B.R. Sorensen, and M.A. Shea. 2006. Calcium binding to calmodulin mutants having domain-specific effects on the regulation of ion channels. Biochemistry. 45:14311–14324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.M., X. Zeng, and C.J. Lingle. 2002. Multiple regulatory sites in large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature. 418:880–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W., H.W. Lee, H. Hellinga, and J.J. Yang. 2002. Structural analysis, identification, and design of calcium-binding sites in proteins. Proteins. 47:344–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap, K.L., J.B. Ames, M.B. Swindells, and M. Ikura. 1999. Diversity of conformational states and changes within the EF-hand protein superfamily. Proteins. 37:499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley, J., B.P. Leroy, N. Hart-Holden, B.A. Lafaut, B. Loeys, L.M. Messiaen, R. Perveen, M.A. Reddy, S.S. Bhattacharya, E. Traboulsi, et al. 2004. Mutations of VMD2 splicing regulators cause nanophthalmos and autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC). Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45:3683–3689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K., Y. Cui, and H.C. Hartzell. 2006. The bestrophin mutation A243V, linked to adult-onset vitelliform macular dystrophy, impairs its chloride channel function. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47:4956–4961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K., Y. Cui, and H.C. Hartzell. 2007. Chloride channel activity of bestrophin mutants associated with mild or late-onset macular degeneration. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48:4694–4705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusifov, T., N. Savalli, C.S. Gandhi, M. Ottolia, and R. Olcese. 2008. The RCK2 domain of the human BKCa channel is a calcium sensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:376–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., C.R. Solaro, and C.J. Lingle. 2001. Allosteric regulation of BK channel gating by Ca2+ and Mg2+ through a nonselective, low affinity divalent cation site. J. Gen. Physiol. 118:607–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y., W. Yang, M. Kirberger, H.W. Lee, G. Ayalasomayajula, and J.J. Yang. 2006. Prediction of EF-hand calcium-binding proteins and analysis of bacterial EF-hand proteins. Proteins. 65:643–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]