Abstract

Purpose

Assess the patient-reported time to recovery for quality of life outcomes: post-surgery sequelae, discomfort/pain, oral function, and daily activities following orthognathic surgery

Methods

170 patients (age 14 to 53) were enrolled in a prospective study prior to orthognathic surgery. Each patient was given a 20 item Health-Related Quality of Life instrument (OSPostop) to be completed each post-surgery day (PSD) for 90 days. The instrument was designed to assess patients’ perception of recovery for 4 domains: post-surgery sequelae; discomfort/pain; oral function; and daily activities. Discomfort/pain was recorded with a 7-point Likert-type scale; all other items were measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale.

Results

Post-surgery sequelae, except swelling, resolved within the first week after surgery for over 75% of the subjects. Discomfort/pain and medication usage persisted for two to three weeks after surgery for most subjects. Return to usual activities, except for recreational activities, which took substantially longer, mirrored the resolution of discomfort/pain. Problems with oral function took the longest to resolve, approximately 6 to 8 weeks for the majority of subjects.

Conclusions

Comprehensive daily postoperative patient quality of life data provides the orthognathic surgeon with estimated recovery times in distinct domains. This information is vital in the provision of informed consent as well as pre-operative education of patients regarding peri-operative and post-operative expectations. Ultimately this data can be combined with individual risk factors to provide personalized consent and expectations as well as tailor peri-operative and post-operative management regimens.

Keywords: Orthognathic surgery, post-surgery recovery, medical diary

Introduction

Convalescence following orthognathic surgery is a complex process for the patient and requires the resolution of post-surgery sequelae such as nausea or swelling; the resolution of discomfort/pain; the return to oral function; and return to pre-surgical lifestyle and activity levels. Currently, there is no prospective systematic documentation of the time required for post-surgery recovery. The need for such data is perhaps best illustrated in the diary account written by an orthodontist who had orthognathic surgery with the intent “to give the reader an insight into not only what we fail to tell …patients, but also what they fail to tell us.”1 Pre-surgical counseling of patients is dependent on accurate data on the course of recovery and realistic expectations about the return to pre-surgical health and activity levels.

The structured medical diary is one methodology that has been used to document the health related quality of life and recovery pattern following surgery. This approach has been shown to be an acceptable format for data collection for patients following orthognathic surgery2 and third molar removal3,4 and has been used to assess risk factors associated with prolonged recovery following third molar removal.5–7

The purpose of this study was to assess the patient-reported time to recovery over a 3 month time-frame for post-surgery sequelae, oral function, daily activities, and discomfort following orthognathic surgery for a developmental disharmony.

Methods

170 subjects who presented with a developmental disharmony and were scheduled for an orthognathic surgical procedure between July 2003 and April 2007 agreed to participate in a prospective clinical study approved by the Biomedical Institutional Review Board. Subjects were excluded if they had a congenital anomaly or a history of acute facial trauma; had previous facial surgery; were pregnant; had a medical condition associated with systemic neuropathy (ex., diabetes, hypertension, kidney problems); or were unable to follow written English instructions or unwilling to sign informed consent. The project was described by a research associate and written consent (assent if subject was under 18) and Heath Insurance Portability Act authorization obtained.

Demographic information (age, gender, and race) was collected prior to surgery. On the day of surgery, the surgical assistant recorded the surgical procedures. Surgery was performed by oral and maxillofacial surgery faculty and residents at an academic medical center. All patients had orthodontic appliances in place at surgery and rigid fixation to stabilize bony jaw segments reducing the time interval for maxillomandibular fixation to 2 weeks or less.

A health diary, OSPostop,2 was used to measure the short-term patient-reported health related quality of life (HRQOL) outcomes following orthognathic surgery. Each subject was instructed to complete the diary each post-surgery day (PSD) for 90 days. The diary was designed to assess patient perception of recovery in four main areas: post-surgery sequelae which included feeling anxious, trapped, bleeding, bruising, nausea, food collection in the soft tissue incision, food collection around teeth, bad breath/bad taste, swelling; worst and average discomfort/pain and medication use for discomfort/pain; oral function which included opening, chewing, and biting foods; and daily activity which included sleeping, routine, social and recreational activities. The discomfort items were rated on Likert-like scales from No Discomfort (1) to Worst Imaginable (7). All other items were rated from No Trouble/Concern (1) to Lots of Trouble/Concern (5). The subject was also requested to record whether medications had been taken for discomfort/pain. Medications were categorized as follows: narcotic analgesic; non-narcotic analgesic; and other. A patient’s daily response to each of the items was categorized as 1) recovered defined as “no (1) or slight (2) trouble or discomfort” with that item or 2) substantial concern/ problem defined as “quite a bit or lots” as indicated by a response of 4 or 5 on the 5-point Likert-type scale or 5 to 7 on the 7-point Likert-type scale for discomfort/pain). Estimates of the days to recovery (25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles) for each item were obtained from the cumulative probability distributions from day 1 to day 90.

Subjects were seen by a research associate at each clinical visit with the surgical attending. These visits routinely occurred at one, four to six, and twelve weeks. Subjects were instructed to bring their diaries with them to each clinical visit. Subjects were asked to return by mail any diaries if a clinical visit was missed or the subject neglected to bring their diary with them to an appointment.

Results

170 patients consented to participate in the study and completed at least the first 30 days. The patients who participated were primarily female (65%) and Caucasian (84%). Participants ranged in age from 14 years to 53 years (median = 19 years; IQR = 17–26 years). 40% had a two jaw procedure and 32% had a maxillary procedure only (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Surgical Characteristics of 170 patients

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 110 | 64.7 |

| Male | 60 | 35.3 |

| Caucasian | 143 | 84.1 |

| Other | 27 | 15.9 |

| Median Age / years | 19 (IQ 17 – 26) | |

| <17 | 42 | 24.7 |

| 17–19 | 45 | 26.5 |

| 19–30 | 50 | 29.4 |

| >30 | 33 | 19.4 |

| 2 Jaw | 68 | 40.0 |

| Mandibular Only | 47 | 27.7 |

| Maxilla Only | 55 | 32.3 |

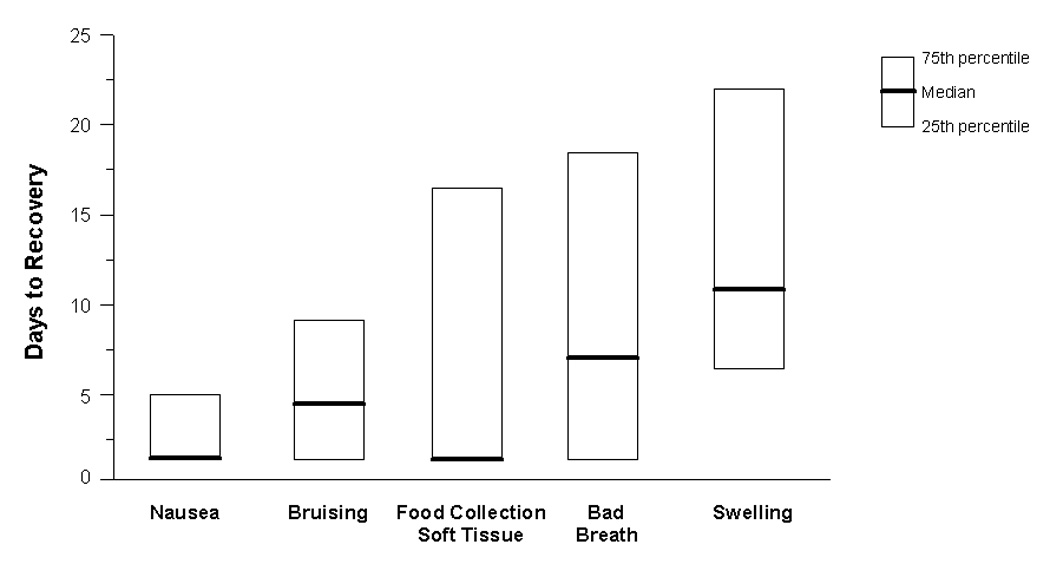

By the end of the first week after surgery, PSD 7, the majority of subjects reported only slight or no problem with nausea, bruising, or bleeding or food collection in the soft tissue incision (Figure 1). Very few subjects (<7%) reported substantial problems for any of these symptoms after PSD 14 (Figure 2A). The concern about a bad taste or bad breath and food collection resolved for most patients during the second post-operative week (Figure 1) although 11% and 20% of the patients reported substantial problems with bad taste/bad breath and food collection in and around the teeth on PSD 14 (Figure 2B)

Figure 1.

Descriptive Statistics for the Number of Days until Recovery (No or Only Slight Trouble or Concern) from Peri-operative Sequelae

Figure 2.

Percentage of Patients Each Day who Reported a Substantial Problem associated with Peri-operative Sequelae

2A: Nausea, Bruising, Food Collection

2B: Bad Breath, Swelling

Figure 3.

Descriptive Statistics for the Number of Days until No or Only Slight Discomfort was Reported and until Medication for Pain or Discomfort was Discontinued.

Resolution of swelling took approximately one to two weeks longer than other immediate post-surgery sequelae. 75% of the subjects reported no or only slight problem with swelling by day 22 after surgery (Figure 1). Of the 25% who perceived that swelling was still a problem or concern, less than 10% perceived it as substantial. By PSD 30 that percentage had decreased to 3% (Figure 2B).

Feelings of discomfort/pain persisted for two to three weeks after surgery. 75% of the subjects reported only slight or no average discomfort during the day by PSD 18 although episodic “worst pain” took longer to resolve (Figure 3). By PSD 30, only 12% and 25% of the subjects reported that the “average daily” and “worst” discomfort/pain had not resolved. By the end of the first month, “worst discomfort/pain” and “average daily discomfort” were reported as substantial by only 4% and 1% respectively (Figure 4). However, 20% of the subjects reported still taking medications for pain/discomfort (Figure 5). Of those taking medication on PSD 30, 4% were taking narcotic analgesics and 16% non-narcotic analgesics. The percent of subjects reporting the use of narcotic medications declined rapidly after surgery: less than 20% by the end of two weeks and 10% by the end of three weeks. The use of non-narcotic analgesics declined more slowly (Figure 5)

Figure 4.

Percentage of Patients Each Day who Reported a Substantial Problem associated with Discomfort / Pain

Figure 5.

Percentage of Patients who Reported Taking a Narcotic or Non-Narcotic Analgesic Each Day for Discomfort / Pain

Return to “normal”, i.e. no problem with sleeping, talking, everyday routine, and social life, mirrored the resolution of discomfort / pain. (Figure 6) Less than 15 percent of the subjects reported substantial problem with everyday activities by PSD 30 and less than 5 percent by day 45 (Figure 7). Feeling comfortable returning to usual recreational activities took substantially longer (Figure 6). Forty percent of subjects still reported substantial problems with regard to recreational activities on PSD 30 and 11 % on PSD 45 (Figure 7)

Figure 6.

Descriptive Statistics for the Number of Days until No Trouble or Concern was Reported for Participating in Daily Activities

Figure 7.

Percentage of Patients Each Day who Reported a Substantial Problem Participating in Daily Activities

Problems with eating, chewing, and opening took the longest to resolve, approximately 6 to 8 weeks. 75% of the subjects reported no or only slight problem with opening at PSD 64 but not until PSD 70 for chewing (Figure 8). Approximately 15% of the subjects were still experiencing substantial difficulty with oral function on PSD 60 (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Descriptive Statistics for the Number of Days until No Trouble or Concern with Oral Function was Reported

Figure 9.

Percentage of Patients Each Day who Reported a Substantial Problem with Oral Function

Discussion

Health diaries can provide a day-by-day characterization of recovery that is important for informed consent and for patients’ understanding of treatment options. Ultimately this information can be used to provide patients with realistic post-surgical recovery expectations, improve the delivery of informed consent, and help tailor treatment regimens based upon identified patient and surgical factors. The recovery patterns observed in this study are likely representative of young, Caucasian patients following orthognathic surgery for a dentofacial disharmony. The generalizability of these data to a more diverse ethnic/racial population of patients or to those with congenital syndromes is unknown.

For most of the patients, the resolution of the post-surgical sequelae, except swelling, occurred within the first week (Fig 1, Fig 2). Post-operative bleeding, nausea and vomiting (PONV) are common occurrences following orthognathic surgery. Serosanginous nasal and post-nasal drainage is expected following maxillary osteotomy and systemic and/or local alpha-adrenergic agents are commonly used for post-surgical management. Younger patients (15 to 25 years of age), those with a prior history of PONV, surgical procedures longer than 1 hour, maxillary surgery, use of inhalational agents, use of post-operative opioid analgesics, and those who report a high pain level in the recovery room (PACU) may be more likely to experience PONV during the first 24 hours after surgery.8 PONV can be quite distressing to patients and caregivers whether it occurs before or after discharge. Not only is PONV associated with a number of sequelae including dehydration, electrolyte disturbance, wound dehiscence, bleeding, aspiration and dislodgement of fixation but patients who experience PONV post-discharge are more likely to report problems or difficulty in returning to normal daily activities.9 Current post-surgical management approaches to minimize PONV post-discharge do not appear to have substantially reduced the percentage of subjects who experience PONV. The percentage of subjects in this study who reported at least some problem associated with PONV during the first five days after discharge closely approximates the 35% reported by Carol et al in 19959 following diverse surgical procedures performed under general anesthesia. Although several factors contribute to the problem including the reduction in red cell mass during surgery, dehydration, altered diet and the frequency and dosage of post-surgery pain medications, interventions to reduce the frequency of PONV should be pursued.

Interestingly, a slightly higher percentage of subjects report difficulty with food collection in surgical sites and bad taste/breath following orthognathic surgery than following third molar removal. Most of the patients in both groups tend to report these problems have resolved by the end of the first post-surgery week but these concerns continued to be reported as problems for 15 to 20% of patients following 3rd molar removal3. Almost 50% of the orthognathic surgery patients reported that these issues caused at least some concern on PSD 7.

The length of time until the resolution of “discomfort/pain” was in-between that for the resolution of post-surgery sequelae and the return to “normal” oral function. The majority of patients reported only slight or no “discomfort” and discontinuation of medication to relieve discomfort/pain two to three weeks after surgery although 20% of patients were still taking analgesics 30 days after surgery. More patients reported taking pain medications than reported substantial average discomfort at each post-operative day. This data, and that reported following third molar removal,10 suggests that requesting patients to quantify “pain” or “discomfort” on visual analog or numerical rating scales during recovery may not accurately summarize the overall amount of post-surgical discomfort since patients are reporting taking pain medication for longer periods of time than they report discomfort/pain.

Discomfort and continuing problems with oral function did not seem to negatively affect subjects’ routine activities. The median days to no or slight interference with routine activities and worst discomfort was approximately the same (~12 to 15 days) while the median days to recovery for oral function was substantially longer. While the “average” patient may be able to return to work or school approximately 2 weeks after surgery,11 25 to 33% of patients may not be sufficiently recovered to return that early. Since a delay in return to routine activities may represent an opportunity cost to patients, it may be prudent to advise patients before surgery to be prepared for a 3 week absence. Return to recreational activities took substantially longer, approximately 6 weeks. These timeframes are similar to those reported previously.11,12

In general, no obvious improvement in post-surgery recovery patterns following orthognathic surgery have occurred in the past decade. Some consideration should be given to changes in surgical or post-surgical management protocols that could decrease discomfort and general “ill health” following orthognathic surgery. The medical diary provides an objective method to measure the impact of alternative clinical practices to reduce postsurgical discomfort and expedite a return to full recovery.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the patient care coordinators, Atousa Safavi and Kaitlin Strauss, and Debora Price, the applications programmer, for their assistance with this project. This project was supported by NIH R01 DE005215.

Source of Support: NIH grant R01DE005215 (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Murphy TC. The diary of an orthognathic patient aged 30 ¾. J Orthod. 2005;32:169. doi: 10.1179/146531205225021051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phillips C, Blakey GH. Short-term recovery after orthognathic surgery: a medical daily diary approach. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.07.005. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conrad SM, Blakey GH, Shugars DA, Marciani RD, Phillips C, White RP., Jr Patient’s perception of recovery after third molar surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:1288. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(99)90861-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White RP, Jr, Shugars DA, Shafer DM, Laskin DM, Buckley MJ, Phillips C. Recovery after third molar surgery: Clinical and health-related quality of life outcomes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:535. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips C, White RP, Jr, Shugars DA, Zhou X. Risk factors associated with prolonged recovery and delayed healing after third molar surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1436. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foy S, Shugars D, Phillips C, Marciani R, Conrad S, White RP., Jr The impact of intravenous antibiotics on health-related quality of life outcomes and clinical recovery after third molar surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:15. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stavropoulos MF, Shugars DA, Phillips C, Conrad SM, Fleuchaus PT, White RP., Jr The impact of topical minocycline with third molar surgery on clinical recovery and health related quality of life outcomes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1059. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silva AC, O’Ryan F, Poor DB. Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) after orthognathic surgery: A retrospective study and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1385. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrol NV, Miederhoff P, Cox FM, Hirsch JD. Postoperative nausea and vomiting after discharge from outpatient surgery centers. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:903. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199505000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snyder M, Shugars DA, White RP, Jr, Phillips C. The role of pain medication after third molar surgery in recovery for lifestyle and oral function. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1130. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neuwirth BR, White RP, Jr, Collins ML, Phillips C. Recovery following orthognathic surgery and autologous blood transfusion. Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg. 1992;7:221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickerson HS, White RP, Jr, Turvey TA, Phillips C, Mohorn DJ. Recovery following orthognathic surgery: Mandibular bilateral sagittal split osteotomy and Le Fort I osteotomy. Int J Adult Orthod Othognath Surg. 1993;8:237–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]