Abstract

Objective:

To describe a formal process designed to determine the nature and extent of change that may enhance the depth of student learning in the pre-professional, clinical chiropractic environment.

Methods:

Project teams in the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) School of Health Sciences and the Division of Chiropractic explored questions of clinical assessment in several health care disciplines of the School and the issue of implementing change in a manner that would be embraced by the clinicians who supervise student-learning in the clinical environment. The teams applied to RMIT for grant funding within the Learning and Teaching Investment Fund to support two proposed studies.

Results:

Both research proposals were fully funded and are in process.

Discussion:

The genesis of this work is the discovery that the predominant management plan in the chiropractic teaching clinics is based on diagnostic reductionism. It is felt this is counter-productive to the holistic dimensions of chiropractic practice taught in the classroom and non-supportive of chiropractic's paradigm shift towards wellness. A need is seen to improve processes around student assessment in the contemporary work-integrated learning that is a prime element of learning within the clinical disciplines of the School of Health Sciences, including chiropractic.

Conclusion:

Any improvements in the manner of clinical assessment within the chiropractic discipline will need to be accompanied by improvement in the training and development of the clinicians responsible for managing the provision of quality patient care by Registered Chiropractic Students

Key Indexing Terms: Competency-based Education; Education, Health; Chiropractic.

Introduction

It is generally accepted that chiropractic developed as a distinct concept of health care from the intellectual constructs of David Daniel Palmer some 112 or so years ago. Palmer lived in rural America but was no fool. There is evidence he was a man of his times who while failing to contribute to the flimsy base of formal literature of that era never-the-less kept himself well informed on developments in the then rather tenuous field of medicine.1, 2

Palmer's essential premise was some form of relationship between changes to the normalcy of the spine, being the distributor of the nervous system, and ill-health or as he termed it dis-ease as a shift in the patient away from health.3 Palmer was not alone with these thoughts; the related healing discipline of osteopathy arose in the United States at that time. Various countries around the world also had traditional concepts of mechanical medicine, such as the bone-setters of Finland, the Hilot Healers of the Philippines, and the Tui Na practitioners of China and East Asia.

From its small beginning and regardless of a proven organized campaign by political medicine in the USA to denigrate and eliminate chiropractic4–6 it has not only survived as a discipline in North America but has grown to be a global practice.7 Today some form of chiropractic is practiced as chiropractic in almost 80 countries. Quite a number have established the necessary legislation to recognize and regulate the practice of chiropractic and many are currently contemplating such socially pro- gressive development.

This relentless growth of a health-care discipline brings with it a commensurate demand for education and today there are more or less as many formal educational programs in chiropractic outside the USA as there are within those states. The greater majority of programs outside the USA are within publicly-funded universities with large student enrolment, a broad base of academics, and direct accountability to government.

In 1997, revised in 2001,8 the World Federation of Chiropractic (WFC) published an Education Charter to guide the development of programs of chiropractic education in countries where such programs have not previously existed. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has more recently published WHO Guidelines on basic training and safety in chiropractic.9 That document outlines what many countries now see as the template for establishing internationally equivalent chiropractic education, although the notion of true international equivalence may be false.10

The major regions of the world (Europe, Australia and East Asia, Canada, and the USA) each have a Council on Chiropractic Education (CCE) meant to establish minimum standards for chiropractic education. These regional Councils are overseen by a Council on Chiropractic Education International (CCEI), the purpose of which remains unclear in spite of a recent attempt to describe its history and role.11 Each regional CCE has the responsibility to assess programs of chiropractic education in their region11 with a view to recommending to the legally responsible authorities such as state, territory and national registration boards those institutions and programs that may be deemed ‘accredited’ and thus formally recognized for a variable period of time.

The region in which the university of the authors of this paper primarily operates is within the purview of the Council on Chiropractic Education Australasia Inc (CCEA). Within this region it is mandatory to graduate from an institution recommended for accreditation by the CCEA if one wishes to register to practice in Australia or New Zealand.

Meanwhile there are questions about accountability within the accreditation process.12 There is also some sense of concern in other health disciplines that accreditation may actually hinder innovation (personal observation, structured platform debate, International Medical Education Conference, Kuala Lumpur, 2007). These in turn raise the question of where to look for leadership in the development of the chiropractic curriculum.

Educational institutions continue to be faced with innumerable demands on the content, length and structure of their programs. The society in which each institution finds itself is also changing at a rapid pace, for example Australia, in common with many societies is an ageing community. As every health economist knows an ageing community brings with it specific and unique demands for its future health care needs. Australia is also expanding the breadth of the primary health care services provided to the community as is evidenced by the contemporary call by government for a greater emphasis on mental health in all health curricula,13 including chiropractic.

This point sets the theme of this paper, namely how to ensure programs in chiropractic education remain relevant to the society in which they operate? How can the pedagogy of chiropractic programs change to reflect contemporary theories of learning when accreditation standards reflect a curriculum first designed for implementation in 194512 and which has undergone little, if any, structural change since?

The process has been stimulated by a review of diagnostic terms which discovered that the term vertebral subluxation complex (VSC) is rarely used within diagnoses constructed by students in the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) chiropractic teaching clinics.14 It is thought that reliance on quantitative measurement of student performance may be the driver for diagnostic reductionism to terms such as biomechanical joint dys- function and resultant management plans that de-emphasise an holistic approach to the patient.14

These discoveries seem to be the antithesis of the principles that underpinned the development of chiropractic as a distinct health discipline, described above. Further they seem to be an anathema in an environment where the profession's peak representative body in Australia has a commitment to broadening the scope of chiropractic practice to include a wellness paradigm.15–17

This current paper addresses the question of how change may be effected within the clinical learning component of a chiropractic program where the accreditation environment perpetuates restrictive quantitative measurement of student development. The authors look at this question from the viewpoint that chiropractic clinical learning must reflect the communities and societies in which the discipline is taught, legislated and practiced. At the same time it must be educationally sound.

Spine Therapists or Health and Wellness Practitioners?

The argument as to whether chiropractors should be providers of holistic health care or of limited care as spine therapists has been well exercised in the chiropractic literature. Nelson18, 19 and others20 take the view that chiropractors should concentrate on the spine and its attendant problems of back pain, neck pain and headache. One of the authors of this paper (PE) has argued this is professionally restrictive and destructive.21, 22

The paradox is that should there be merit in Nelson's argument, the current developments in the chiropractic curriculum would appear to be working to the contrary. Instead of the holism of well-being the curriculum descends to become reductionistic and spine-only. But then chiropractors are meant to hold supremacy in the field of non-surgical spinal treatment so it would be reasonable to see evidence of discipline-specific expertise and language. The observational evidence of the authors is that a number of colleges in North America no longer teach the traditional listings long associated with chiropractic assessment of the spine, nor segment-specific adjusting. Indeed, the term chiropractic adjustment seems to have been almost replaced by the more generic term spinal manipulation.

The argument is mounted that the term biomechanical joint dysfunction is acceptable and understood within the broader context of the language of medicine while the term VSC is not understood by anyone other than most chiropractors and that listings are irrelevant. Budgell et al.23 have provided a contextual correction to this argument by describing the words used by chiropractors as being a dialect of a universal biomedical language. The onus thus returns to the chiropractor to appreciate and understand the different dialects within the shared language of biomedicine.23

It would not seem appropriate for any person wanting to be seen as a spinal care expert to reduce or devalue unique terms within their dialect. One would think that any group that asserts itself as expert would make the intellectual effort to better understand these matters through research and scholarship.

Shifting Towards Wellness

Informed writers such as Jamison24 and Hawk25–27 put forward a convincing case for chiropractic to lead a transition to wellness-based health care. In this world the chiropractor speaks a dialect that is generic among all health care providers in the community while retaining their unique skill-set of spinal adjustment that has long distinguished the discipline.

Chiropractors also have the appropriate foundation in primary care skills to allow further training to meet the developing range of demands on health workers, such as aged care, palliative care, mental health, rural health and indigenous health. It is argued by the authors that chiropractors are well positioned to successfully transition to this field while retaining their discipline-specific dialect and behaviors, including their deep philosophical understanding of human well-being.

A clear divide is evident between the paradigm put by Jamison24 and Hawk25–27 which represents the emerging scope of chiropractic practice described above and the limited scope, restricted to the spine, favored by Nelson and colleagues.18–20

This paper argues the emerging scope of chiropractic practice delineated by Jamison24 and Hawk25–27 is in effect the 21st Century paradigm for chiropractic. Paradoxically, given the introductory comments regarding Palmer, everything old becomes new again.

A shift towards this 21st Century paradigm demands a shift in the future outcomes of chiropractic clinical education. Graduates suited to the new paradigm will need to be distinct from those supposed spine specialists too afraid to speak a professional dialect. They will need to demonstrate a level of clinical decision making that is beyond diagnostic reductionism. They will need to be respectful of the potential of the chiropractic adjustment as opposed to generic mobilization, a low-order form of manipulation.

These graduates will need new clinical skill-sets to better match them into a more diverse range of communities and practice environments. They will come to again demonstrate within this new paradigm the traditional attributes28–31 of chiropractic which include holism, naturalism and vitalism. It is within these attributes that weight management, nicotine habits, chemical abuse and all the other elements associated with human wellness and quality of life become an inseparable element of chiropractic management.

The Paradigm Shift

The paradigm shift has been clearly proposed by Jamison and Hawk among others. Authoritative discussion is starting to appear in the literature32 about how chiropractic education must also change to remain supportive of the directions the discipline is taking. Indeed the World Federation of Chiropractic sponsors a biannual conference33 on education that discusses broad directions for the curriculum.

However any new way of thinking about chiropractic education in general and its clinical learning in particular must take into account as broad a church as possible. It must accept there are chiropractors who will practice only in accord with a particular type of evidence while there are others who open the book more widely and then again those who close it and follow their intuition, There are those who will practice hands only spine only in a single doctor practice while there are others who are also orthopaedic surgeons or medical neurologists and practice their own learned version of chiropractic within a medical setting.

On closer inspection there is a commonality in that at some time, most chiropractors will do something with or to the spine. Whether it is an adjustment or some lesser intervention is a question to be explored at another time. But if we accept that chiropractors are likely to offer a clinical intervention about the spine we can accept that the WFC Identity Statements34 are fairly close to the mark.

There is a foundation of shared belief that the health status of the spine has some relationship to the health status of the patient. There is also a growing number of chiropractic academics with formal training in education and a commensurate attention to the pedagogies designed and imple- mented into the curriculum. The benefit of this is a growing demand by educators for evidence-influenced material in the classroom, which in turn is a stimulus for new ways of thinking about tomorrow's practice of chiropractic.

This paper argues that the WFC Identity of chiropractic is integral with the 21st Century paradigm. The authors also argue that chiropractic clinical education must transform to reflect this while re- specting established educational theories and practice. In order to move in this direction we now describe a structured process in which the required actions are informed by evidence and will be mea- sured for outcomes.

This paper is the first in what will become a longitudinal, contemporaneous case study in chiropractic education. Subsequent papers will report the actual evidence-informed activity and its outcomes, and then a measure of student satisfaction with the new process.

Methods

A review of some 400 individual patient records generated over a 6 month period from October 2006 to March 2007 by students undertaking chiropractic clinical education with RMIT University revealed only 5 diagnoses outside a biomechanical context.14 Of 355 diagnoses that were related to the spine the greater majority (93.6%) resorted to diagnostic reductionism expressed as basic biomechanical descriptors.14

While these simple facts provide an appropriate outcome measure for any change process, other outcomes measurements will need to be developed to inform this process as to whether the effects are as they are expected to be, or perhaps whether the problem continues to be compounded. However before we discuss outcomes, we must determine the processes. The authors are aware of a range of learning and teaching dimensions involved with the delivery of clinical education programs that are expected to achieve deep learning and Professional Knowledge.

The RMIT University Strategic Plan sees clinical education as being work-integrated learning that should provide the student with a global passport to facilitate seamless mobility throughout the various communities of the world. To this end it has a campus in Melbourne that is celebrating 120 years of industry engagement (32 years for the chiropractic program) and a formal campus in Vietnam that is providing 21st century opportunities within our region of influence. In addition there are numerous programs delivered in multiple offshore locations, not the least being RMIT's valued partner in Tokyo coming to celebrate in 2008 its 14th year of successfully delivering an international standard chiropractic program that is fully accredited.

The University has set a strategic direction inten- ded to result in strengthening the learning experience of all students. Early in 2007 the Deputy Vice Chancellor (Academic) called for expressions of interest from staff to design and undertake discreet research activities with the purpose of better informing the improvement of our capability with elements such as work-integrated learning and global passports. The framework for this was termed the Learning and Teaching Investment Fund (LTIF).

In response to this call several staff of the Division of Chiropractic explored opportunities embedded in the Division Strategic Plan and its learning and teaching activities that were of sufficient substance to warrant an application for funding through the LTIF. Project teams formed and unanimously determined that the clinical learning experience demanded im- provement. The chiropractic teams were mindful that every accreditation visit over many years, regardless of the body involved, pointed to a need to change something within the way the university delivered its clinical learning experience for chiropractic students.

From this a clear pathway was identified for change. Three team members became the authors of this and a related paper14 and determined it was well past the use-by date to continue fluffing around the edges of our clinical education process in the hope of satisfying one accreditation inspection while fully knowing the next would find fresh matters to address.

The team members addressed the theme at workshops during an international education conference in Kuala Lumpur in mid 2007 and a process for change emerged. This process distilled to there being two significant tasks to complete. Each task was written as a grant application and submitted as separate funding requests for grant monies from the LTIF and each has subsequently been supported to a total of $60,000. The two projects are described below.

Results

This is a school-wide project based in the Division of Chiropractic. It aims to undertake a major review of the clinical learning activities of the Division of Chiropractic and map these processes, including assessment, against concurrent reviews of clinical learning in the Divisions of Nursing, Psychology, Disability Studies and Chinese Medicine (these Divisions, together with the Division of Osteopathy, form the School of Health Sciences).

There will be a literature review and structured interviews with other institutions with similar practices, in particular RMIT Japan, the New Zealand College of Chiropractic, and the International Medical University in Kuala Lumpur. The latter is becoming a partner institution with RMIT University and delivers medical education that allows students to transfer to one of 28 partner universities around the world or continue in IMU's own medical program. It is intended that from 2008 IMU will deliver a Bachelor degree equivalent to the RMIT Melbourne Bachelor in the chiropractic program, allowing direct entry from IMU into the RMIT Master of Clinical Chiropractic.

The project also includes a series of consultations with the industry partners of the Division of Chiropractic, including the CCEA and the Chiropractors Association of Australia (CAA) and the Chiropractors Registration Board of Victoria (CRBV). These will aim to identify and describe the critical clinical capabilities of graduates and the desired competencies of clinical supervisors. This latter point will feed into the second research project.

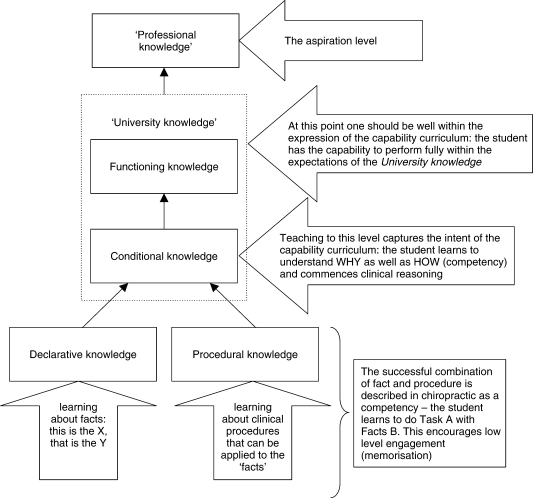

The University has taken a fundamental shift to view clinical education as work-integrated learning (WIL), whether it occurs in the on-campus clinics or other approved locations. A benefit of this is alignment with a modified Bigg's hierarchy of knowledge (Fig 1) that demonstrates the need to shift beyond University knowledge to attain Professional knowledge. It would appear that WIL represents the most appropriate pedagogy to facilitate this deeper learning.

Figure 1.

A hierarchy relating competency and capability to knowledge development. Reproduced with permission from Ebrall.35

Therefore this stage of Project One will also seek to identify exemplars and standards of WIL assessment practice from all participating disciplines and institutions and the required elements of WIL partnerships that focus on clinical assessment and the provision of feedback to inform/enhance practice and clinical learning.

The Project Team will achieve this by conducting student focus groups to identify the forms of feedback that are valued by students to enhance and inform their clinical practice; how assessment tasks and approaches measure learning and skills relevant to critical aspects of work readiness; and the likely issues in bridging the theory/practice nexus.

Finally the Team shall also conduct School-based workshops to identify the challenges in WIL assessment in other disciplines and will explore solution options with a view to establishing School-wide principles, guidelines and practices in assessment and feedback in clinical WIL.

There is a significant presence of WIL in the chiropractic program. It features in the Master pro- gram as 4 courses delivered sequentially as one per semester to account for 25% of the student's total credit point load. A further 25% is delivered as a Research and Scholarship Portfolio (RaSP) and the remaining 50% as classroom instruction to support both WIL and RaSP. There should be significant benefits to the chiropractic program from the application of the outcomes of this project.

The authors understand that successful and relevant formative feedback is critical to achieve the desired shift from simple clinical competency to the more complex clinical capabilities expected of registered health professionals. It should not be over-looked that from July 2007 all Victorian chiropractic students engaged in clinical placement are required to be Registered Chiropractic Students with the Chiropractors Registration Board of Victoria.

The non-chiropractic disciplines within the School may take the outcomes of this project as drivers of the development of pilot implementation plans to trial various new approaches in practice. However the authors expect the specific outcomes for chiropractic to include the design and implementation from 2008 of a completely new approach to the delivery of patient care in the University's chiropractic teaching clinics.

While it is too early to predict what shape this may take it will need to include appropriate improvements in the assessment of students in the University's WIL environments. The Division of Chiropractic in conjunction with the CCEA and the CRBV will closely monitor this process with a view to identifying recommendations for improvements and further implementation.

Project Two

The authors appreciate that the significant change intended to flow from the above project can only be optimised through a team of clinicians who are informed, supportive, and appropriately trained.

Therefore this parallel project involves the con- struction, development and implementation of a clinician training program with the specific objective to integrate the curricula content and pedagogy to which students are exposed during the academic and clinical components of their pre-professional training as chiropractors at RMIT. The primary focus group will be staff involved in the clinical education of students.

The project will develop audiovisual material to be placed into an electronic learning environment and will include instruction and assessment in the following areas: University and Division policy; teaching and learning in the clinical setting; assessment and diagnosis; therapeutic and management principles; scope of practice; clinical research.

The resultant training program will be delivered and assessed in an electronic format allowing flexible access for staff who are employed by the University on a casual or sessional basis. Accordingly there will be a need to construct and develop written content and audio and video footage and files and to place these into interactive programs which will allow the completion of on-line quizzes, participation in discussion boards, and various methods of self-assessment. Once established the program will remain available for use by new and for review by existing staff. The generic educational nature of much of the content allows the potential for it to also be a resource for other disciplines of the School.

The Division of Chiropractic sees the successful fruition of this project as critical to the success of the intended shift in our model of clinical learning. A driver was the realization there are no meaningful selection requirements listed for the position of sessional clinician short of the applicant holding current registration as a chiropractor in the state of Victoria and having engaged in a minimum of 3 years of vocational practice.

Once contracted, there are no transition or mentor schemes to assist new staff and no ongoing training or professional development opportunities or re- quirements which might allow or demand staff to consolidate or upgrade their skills. As most clinical educators engage in private practice at times when not in the University clinics there are few if any opportunities for clinical educators to interact or share information with those involved in classroom teaching (referred to as academic staff) or for that matter, with each other. Similarly, academic staff find little time to visit or teach in the clinics.

The fact that clinicians have little formal exposure to what is taught by academic staff means they must essentially interpret the contemporary status of academic content and intent on the basis of their interaction with students. This can represent a significant hurdle in their ability to appropriately reinforce the knowledge and skills students acquire in the academic components of the program. In turn this leads to an erosion of that knowledge and skill-base and can perversely force students to adopt what may be a new and contradictory set of principles and methods according to what individual clinical educators may be comfortable with from their own educational experience. The result is that clinical learning is driven by the ‘n of 1’ where the individual clinician's experience, no matter how dated, becomes the driver of the students' clinical learning and the contemporary, informed views of the academic group are diminished if not excluded.

This may well be a reason for the findings reported in the related paper that clinical students tend not to apply diagnostic terms such as vertebral subluxation complex14 taught in the pre-clinic years and are equally reluctant to look beyond a reductionistic mechanical approach to management in spite of the holistic attributes included within the pre-clinic years.

Discussion

In common with many other countries, Australian society is ageing. There is also an increasing need for primary contact mental health services and a sensitivity for palliative care. Governments are driving active agendas to unbundle medicine's monopoly of the provision of these services with a view to having a more diverse range of health workers delivering a broader type of primary care. While these changes are occurring within a complex political environment, the curriculum remains insulated within a static educational environment. By and large it seems chiropractic programs remain rusted in curricular concepts from the 1940s12 in the absence of innovative leadership from chiropractors with formal training in education as well as their discipline. Trained educators of chiropractors are few and far between in the accreditation bodies and registration boards which compounds the question of how to achieve appropriate and relevant curriculum development.

This point encapsulates the theme of this paper, namely how to ensure programs in chiropractic education remain relevant to the society in which they operate? How can the pedagogy of chiropractic programs change to reflect contemporary theories of learning in the current regulatory environment?

The results reported in this paper are the formation of project teams with defined roles and a purpose to use appropriate research methodology to identify ways to improve. The work was initiated by a review of clinical diagnoses which revealed the term vertebral subluxation complex is rarely used within diagnoses constructed by students in the RMIT chiropractic teaching clinics.14

Our initial, reactive thinking is that reliance on quantitative measurement of student performance may be the driver for diagnostic reductionism to terms such as biomechanical joint dysfunction and resultant management plans that avoid an holistic approach to the patient. The research described in this paper will inform this question when it is reported in a subsequent paper. It is the authors' expectation that contemporary pedagogical strategies will be identified and then underpin a significantly enhanced method of learning and assessment within the clinical WIL that is supported by trained clinicians and connected clinical educators.

Conclusion

The authors appreciate that exposure to a diversity of styles and opinions can enrich the student whereas a lack of consensus on fundamental principles of the chiropractic discipline fosters confusion and frustration. We are also aware that an ongoing criticism aired by students is the perception they must serve a variety of masters during their clinical training, each with their own interpretation of what a chiropractor does and how this is to be best achieved. The situation is compounded during final examinations where students must again face academic staff who have attempted to imbue within them knowledge and skills that may now be repressed.

This paper has described two formal research projects designed to determine the nature and extent of change that should address this disconnection by enhancing the depth of student learning and assessment in the pre-professional, work-integrated clinical chiropractic environment. It is felt that appropriate training for clinicians is an important factor in achieving a connected assessment process that is integrated with such change. The desired outcomes are significant change in the manner of clinical assessment within the chiropractic teaching clinics of the University and improvement in the training and development of the clinicians responsible for managing the provision of quality patient care by Registered Chiropractic Students.

Notwithstanding the belief that various views of experienced clinicians may provide an important contribution to vocational training there remains an equal and urgent need for students to receive consistency of message, method and expectation as it concerns their educational experience. A more formal challenge is that found within the RMIT Division of Chiropractic where the authors see a significant need to integrate curriculum content, pedagogy, objectives and expectations within both the academic and clinical components of the program. We contend that the two projects described in this paper may make a significant contribution to achieving this outcome.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant funding from RMIT University's Learning and Teaching Investment Fund.

Contributor Information

Phillip Ebrall, Division of Chiropractic RMIT University.

Barry Draper, International Chiropractic Programs, Division of Chiropractic, RMIT University.

Adrian Repka, Chiropractic Clinical Education, Division of Chiropractic, RMIT University.

References

- Ebrall PS. A review of the practise of medicine in 1895. Chiropr J Aust. 1995;25:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrall PS. A review of the neurological concepts of 1895. Chiropr J Aust. 1995;25:56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer DD. The science, art and philosophy of chiropractic. Portland, Oregon: Portland Publishing House; 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman-Smith DA. The Wilk case. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1989;12:142–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk CA. How I got involved in a lawsuit against the AMA. Todays Chiropr. 1995 Jan–Feb;24(1):54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wilk CA. A sequel to the most prevalent health care fraud: our strategy and goal for 1995. Am Chiropr. 1994 Nov–Dec;16(6):38–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman-Smith DA. Current status of the profession. In: Chapman-Smith DA, editor. The chiropractic profession: its education, practice, research and future directions. West Des Moines, Iowa: NCMIC Group; 2000. pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- World Federation of Chiropractic [homepage on the Internet] Toronto: Policy statement: International charter for the introduction of chiropractic education; 1997 amended 2001. WFC; [about 3 screens] Available from http://www.wfc.org. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, editor. WHO Guidelines on basic training and safety in chiropractic. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrall PS, Takeyachi K. International equivalency for first-professional programs and chiropractic education. Chiropr J Aust. 2004;34:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Herrity R, Callender A. The Councils on Chiropractic Education—International. Chiropr History. 2007;27(1):81–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrall PS. Commentary: Are we teaching the right courses? Chiropr J Aust. 2007;37:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cole N. Mental Health in Tertiary Curricula. Letter to Council on Chiropractic Education Australasia Inc. COAG Workforce Implementation Taskforce, Australian government Department of Health and Ageing. 2007, January 24. [Google Scholar]

- Repka A, Ebrall PS, Draper B. Failure to use vertebral subluxation complex as a diagnostic term: a flaw of reductionistic diagnosis with resultant compromise of student and patient outcomes in chiropractic teaching clinics. Chiropr J Aust. 2007;37:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Richards D. Creating our future. Wellness turns concrete. Aust Chiropr. 2007 Feb;1:6. [Google Scholar]

- Jamison Jr. The chiropractic practice model: an exploration of international trends. Chiropr J Aust. 1996;26:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson B. Obesity targeted at CAA Wellness workshops. Aust Chiropr. 2007;Mar:1. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CF. Chiropractic scope of practice. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1993;16:488–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CF. Health care reform and chiropractic. Chiropr Tech. 1993;5(4):174–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CF, Lawrence DJ, Triano JJ, Bronfort G, Perle SM, Metz RD, et al. Chiropractic as spine care: a model for the profession. Chiropr & Osteopat. 2005;13:1. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-13-9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1746-1340-13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrall PS. Commentary: Chiropractic and the cul de sac complex. Chiropr J Aust. 1994;24:106–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrall PS. Commentary: Chiropractic and the second hundred years: a shiny new millennium or the return of the Dark Ages? J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995;18:631–5. [Google Scholar]

- Budgell B, Miyazaki M, O'Brien M, Perkins R, Tanaka Y. Our shared biomedical language. IeJSME. 2007:A17. [Google Scholar]

- Jamison Jr. Identifying non-specific wellness triggers in chiropractic care [commentary] Chiropr J Aust. 1998;28:65–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hawk C. The interrelationships of wellness, public health, and chiropractic. J Chiropr Med. 2005;4(4):191–4. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60150-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawk C, Hyland JK, Rupert RL, Odhwani A. Implementation of a course on wellness concepts into a chiropractic college curriculum. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:423–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawk C. Back to basics… toward a wellness model for chiropractic: the role of prevention and health promotion. Top Clin Chiropr. 2001;8(4):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gatterman MI. Teaching chiropractic principles through patient centered outcomes. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 1997;41(1):27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gatterman MI. A patient centered paradigm: a model for chiropractic education and research. J Alt Complement Med. 1996;1:415–32. doi: 10.1089/acm.1995.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatterman MI. Teaching-learning options for the study of chiropractic principles: a case study. J Chiropr Educ. 1992;Dec:93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrall PS. Commentary: The nature of the principles of chiropractic. Chiropr J Aust. 2001;31:98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C. Future trends in chiropractic education. Conference on clinical assessment. J Chiropr Educ. 2007;21(1):34–5. doi: 10.7899/1042-5055-21.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Federation of Chiropractic [homepage on the Internet] Toronto: WFC/ACC Education Conference. WFC; [about 1 screen with optional proceedings] Available at http://www.wfc.org/website/WFC/Website.nsf/WebPage/EventsNew?OpenDocument&ppos=4&spos= 0&rsn=y. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman-Smith D, editor. The spinal health care experts. The profession reaches agreement in identify. Chiropr Rep. 2005;19(4):1–3. 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrall PS. From competency to capability: an essential development for chiropractic education. Chiropr J Aust. 2007;37:61–7. [Google Scholar]