Abstract

The cationic ruthenium-hydride complexes, [(PCy3)2(CO)(CH3CN)2RuH]+BF4− and formed in situ from Ru3(CO)12/HBF4·OEt2, were found to be highly effective catalysts for the C-H bond activation reaction of arylamines and terminal alkynes. The regioselective catalytic synthesis of substituted quinoline and quinoxaline derivatives was achieved from the ortho-C–H bond activation reaction of arylamines and terminal alkynes by using the catalyst Ru3(CO)12/HBF4·OEt2. The normal isotope effect (kCH/kCD = 2.5) was observed for the reaction of C6H5NH2 and C6D5NH2 with propyne. A highly negative Hammett value (ρ = −4.4) was obtained from the correlation of the relative rates from a series of meta-substituted anilines m-X-C6H4NH2 with σp in the presence of Ru3(CO)12/HBF4·OEt2 (3 mol% Ru; 1:3 molar ratio). The deuterium labeling studies from the reactions of both indoline and acyclic arylamines with DC≡CPh showed that the alkyne C-H bond activation step is reversible. The crossover experiment from the reaction of 1-(2-amino-1-phenyl)pyrrol with DC≡CPh and HC≡CC6H4-p-OMe led to the preferential deuterium incorporation to the phenyl-substituted quinoline product. A mechanism involving rate-determining ortho-C–H bond activation and an intramolecular C-N bond formation steps via an unsaturated cationic ruthenium-acetylide complex has been proposed.

Introduction

Considerable research has been directed to the development of catalytic C-H bond activation methods which are applicable to the synthesis of biologically important quinolines, indoles and related nitrogen heterocyclic compounds.1 In part due to their innate ability for functional group tolerance, late transition metal catalysts have been found to be suitable for directing regio- and chemoselective C–H bond activation reactions of nitrogen compounds. For example, Rh and Ir catalysts have been successfully utilized for highly regioselective sp2 C–H bond activation reactions of benzoimidazole and related nitrogen heterocyclic compounds,2 and sp3 C-H bond insertion reactions of amine compounds.3 Chelation control methodology has been shown to be particularly effective for mediating regioselective C–H bond activation reactions of nitrogen compounds,4 and has recently been utilized for the synthesis of pharmaceutically important polycyclic alkaloids.5 Both inter-6 and intramolecular7 oxidative C–H bond activation reactions of indole and pyridine derivatives have recently been achieved by using Pd, Pt and Cu catalysts. A remarkably selective catalytic sp3 C-H bond oxidative amination method has been successfully applied to the synthesis of amino acid derivatives.8

Inspired by recent reports on the unusual reactivity of late-metal amido complexes,9 we have begun to explore the catalytic activity of well-defined ruthenium-amido complexes for N-H and other unreactive bond activation reactions.10 We recently discovered that the cationic ruthenium-hydride complexes are highly effective catalysts for the regioselective intermolecular C-H bond activation reaction of benzocyclic amines with terminal alkynes.11 The catalytic method efficiently produces tricyclic quinoline derivatives from the direct coupling of unprotected amines and terminal alkynes without chelate-directing groups. This report delineates the scope and mechanistic study of the ruthenium-catalyzed C-H bond activation and cyclization reactions of arylamines and terminal alkynes.

Results and Discussion

Reaction Scope

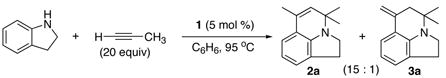

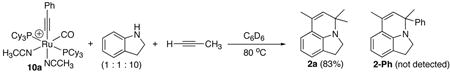

While studying the ruthenium-catalyzed hydroamination and other C-C bond forming reactions, we initially discovered that the cationic ruthenium-hydride complex [(PCy3)2(CO)(CH3CN)2RuH]+BF4− (1) is an effective catalyst for the coupling reaction of benzocyclic amines and terminal alkynes (eq 1).11 For example, the treatment of indoline (30 mg, 0.25 mmol) with excess propyne (20 equiv) in the presence of 1 (5 mol %) in benzene at 95 °C for 24 h cleanly produced the tricyclic products 2a and 3a (15:1) in 81% combined yield (eq 1).

|

(1) |

Since the complex 1 was found to be less effective for electron-deficient terminal alkynes, the activity of commonly available ruthenium catalysts and additives was surveyed to find a suitable catalytic system. The complex Ru3(CO)12 (4) with an additive NH4PF6 or HBF4·OEt2 was found to be the most effective catalyst for the coupling reaction of amines and alkynes.12 For example, 1 mol % of 4/NH4PF6 (1:3 molar ratio) gave a nearly quantitative yield of 2a and 3a (20:1, 99% combined yield) in less than 12 h for the reaction of indoline with propyne. Previously, the catalytic system Ru3(CO)12/NH4PF6 has been utilized for the hydroamination and C-C bond activation reactions.13

The reaction scope of benzocylic amines and alkynes was explored by using the catalytic system 4/NH4PF6. Both 5- and 6-membered benzocyclic amines were found to readily undergo the regioselective coupling reaction with terminal alkynes to give the tricyclic products 2 and 3. In most cases, only trace amounts of the isomerization products 3 were formed. Both aliphatic and aryl-substituted terminal alkynes were found to be suitable substrates, but no coupling product was formed with sterically demanding terminal alkynes such as 3-methyl-1-butyne and internal alkynes. A detailed description of the catalytic reaction has recently been reported.11

|

(2) |

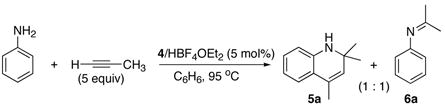

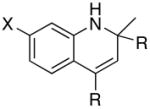

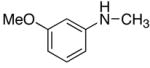

In an effort to extend the scope, we next surveyed the catalytic coupling reactions of acyclic arylamines and terminal alkynes. Initially, the reaction of aniline (50 mg, 0.54 mmol) and excess propyne (2.5 mmol) in the presence of 4/HBF4·OEt2 (5 mol% 2, 1:3 molar ratio) in benzene at 95 °C produced a ~1:1 mixture of the ortho-C–H bond activation product 5a and the hydroamination product 6a in ca. 80% combined yield (eq 2). A few optimization efforts such as increasing alkyne concentration or altering the ratio of catalyst/co-catalyst did not significantly improve the product yield of 5a. The organic products were readily separated by column chromatography and the structure was completely established by spectroscopic methods.

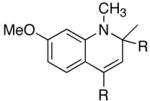

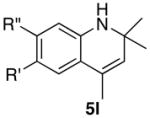

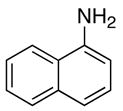

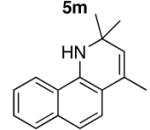

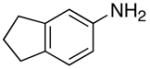

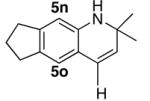

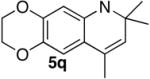

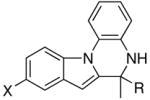

We reasoned that the ortho-C–H bond activation would be strongly influenced by the meta-substituent of arylamines. Indeed, meta-electron–donating group was found to promote the ortho-C–H bond activation of aniline to give the products 5 preferentially over the hydroamination products 6, in which cases, less than 5% of 6 was formed in the crude reaction mixture (Table 1, entries 2–6). Both alkyl– and aryl–substituted terminal alkynes were found to be suitable substrates for the secondary arylamine (entries 8–11). For 3,4-disubstituted anilines, the coupling products 5l and 5m were formed from the ortho-C–H bond activation para to the electron–donating group R″ (entry 12, 13). Similar regioselective ortho-C–H bond activation was also observed for the functionalized bicyclic arylamines to give the tricyclic quinoline products 5n–5q (entries 14–17). In contrast, arylamines with an electron–withdrawing group (e.g., m-chloroaniline) formed <5% of the C-H bond activation product 5 under the similar reaction conditions, giving mostly the hydroamination product (~90%). Substituted hydroquinoline core structure is commonly present in a variety of natural products and pharmaceutical agents.14

Table 1.

The coupling reaction of arylamines and terminal alkynes.a

| entry | amine | alkyne | product | 4 (mol %) | t (h) | yd (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| 1 | X = H | R = Me | 5a | 5 | 24 | 43c |

| 2 | X = Me | R = Me | 5b | 2 | 24 | 83 |

| 3 | X = i-Pr | R = Et | 5c | 2 | 24 | 51 |

| 4 | X = OMe | R = Me | 5d | 1 | 20 | 90 |

| 5 | X = OMe | R = n-Bu | 5e | 3 | 24 | 78 |

| 6 | X = OPh | R = Me | 5f | 2 | 24 | 92 |

| 7 | X = OH | R = Me | 5g | 5 | 24 | 38c |

|

|

|

||||

| 8 | R = Me | 5h | 2 | 20 | 93 | |

| 9 | R = Ph | 5i | 3 | 24 | 88 | |

| 10 | R = C6H4-p-OMe | 5j | 3 | 24 | 69 | |

| 11 | R = 2-SC4H3 | 5k | 2 | 24 | 94 | |

|

|

|

||||

| 12 | R′ = OMe | R″ = OMe | 5l | 1 | 16 | 90 |

| 13 | R′ = Cl | R″ = Me | 5m | 5 | 24 | 42c |

| 14 |

|

5n |

|

4 | 24 | 92 |

| 15 |

|

5o |

|

4 | 24 | 85 |

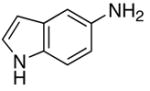

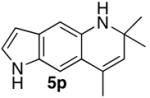

| 16 |

|

5p |

|

4 | 24 | 41c |

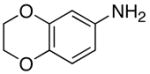

| 17 |

|

5q |

|

2 | 24 | 81 |

Reaction conditions: amine (1.5 mmol), alkyne (5–10 mmol), Ru3(CO)12/HBF4·OEt2 (1:3), benzene (2–5 mL), 90–100 °C.

Isolated yield based on amine.

40–50% of 6 was formed.

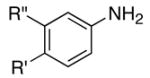

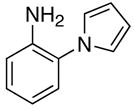

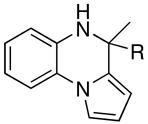

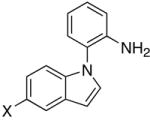

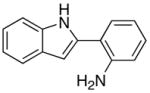

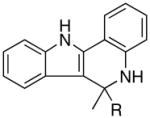

The catalytic method was successfully extended to the synthesis of quinoxaline derivatives (Table 2). Thus, the treatment of 1-(2-amino-1-phenyl)pyrrol with terminal alkynes gave the quinoxaline products 7, in which α-pyrrole sp2 C–H bond has been selectively activated (entries 1–4). Similarly, the coupling products 8 and 9 were resulted from the regioselective C–H bond activation/cyclization of N-(2-aminophenyl)- and 2-(2-aminophenyl)indoles, respectively (entries 5–10). Only one equivalent of terminal alkyne has been regioselectively inserted to sp2 C–H bond to give the cyclic products for these cases. The quinoxaline derivatives have been shown to display a variety of biologically important functions including as agents for the treatment of tuberculosis.15

Table 2.

The coupling reaction of pyrrol– and indol–substituted aniline and terminal alkynes.a

| entry | amine | alkyne | product | 4 (mol %) | t (h) | yd (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| 1 | R = Et | 7a | 1 | 24 | 96 | |

| 2 | R = Ph | 7b | 2 | 24 | 93 | |

| 3 | R = C6H4-p-OMe | 7c | 2 | 20 | 90 | |

| 4 | R = 2-SC4H3 | 7d | 5 | 24 | 92 | |

|

|

|

||||

| 5 | X = H | R = Me | 8a | 2 | 20 | 93 |

| 6 | X = H | R = p-Tol | 8b | 3 | 24 | 75 |

| 7 | X = H | R = C6H4-p-Cl | 8c | 3 | 24 | 70 |

| 8 | X = OMe | R = Et | 8d | 3 | 24 | 82 |

|

|

|

||||

| 9 | R = n-Bu | 9a | 5 | 20 | 70 | |

| 10 | R = Ph | 9b | 5 | 24 | 91 |

Reaction conditions: amine (1.5 mmol), alkyne (2–5 mmol), Ru3(CO)12/HBF4·OEt2 (1:3), benzene (2–5 mL), 90–95 °C.

Isolated yield based on amine.

Mechanistic Study: Isotope Effect

The mechanism of the catalytic reaction was examined by employing both indoline and acyclic arylamines. First, a normal deuterium isotope effect was observed from the reaction of C6H5NH2 and C6D5NH2 with propyne. The pseudo–first order plots of the catalytic reaction of both C6H5NH2 and C6D5NH2 with propyne at 95 °C gave kobs = 9.6 × 10−2 h−1 and kobs = 3.9 × 10−2 h−1, respectively, from which kCH/kCD = 2.5±0.1 was calculated (Figure S1, Supporting Information). In contrast, analogous reactions of m-OMe-C6H5NHCH3 and m-OMe-C6H5NDCH3 with propyne, and aniline with HC≡CPh and DC≡CPh at 95 °C gave negligible isotope effects of kNH/kND = 1.1±0.1 and kCH/kCD = 1.05±0.1, respectively. These results indicate that the arene C-H bond activation is the rate-limiting step for the catalytic reaction.

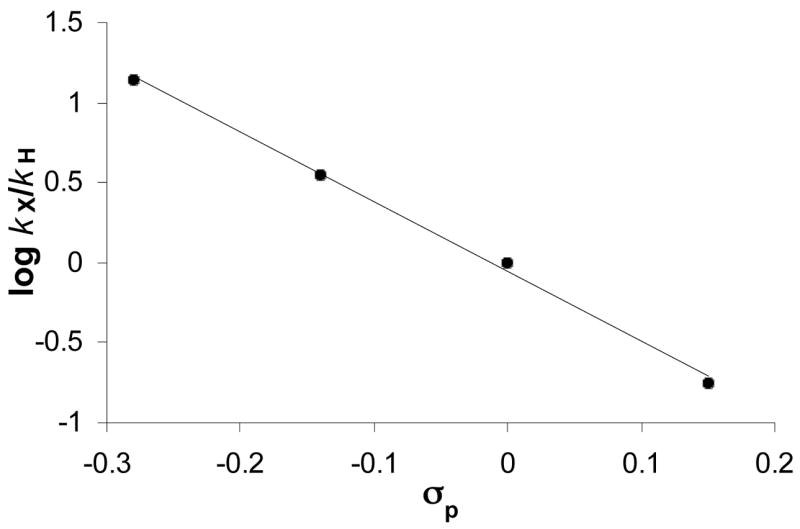

Hammett Study

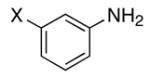

The electronic effect of the ortho-C-H bond activation was examined for a number of different meta-substituted anilines. The Hammett ρ = −4.4 was obtained from the correlation of the relative rates with σp for a series of meta-substituted anilines m-X-C6H4NH2 (X = OMe, CH3, H, F) with propyne in the presence 4/HBF4·OEt2 (3 mol% 4, 1:3 molar ratio) at 95 °C (Figure 1). Such highly negative ρ value has been commonly observed in organic substitution reactions involving a carbocation intermediate.16 In our case, a highly negative ρ value suggests considerable cationic character on the transition state of arene C-H bond activation step via the formation of ruthenium-aryl species. The hydroamination product 6 was formed predominantly for the anilines with an electron-withdrawing group (for example, 85% of 6 and ~10% of 5 for m-F-C6H4NH2), and this may be due to a relatively unfavorable ortho-C-H bond activation compared to the hydroamination reaction path. The fact that no correlation was observed between the relative rates of aniline with aryl-substituted alkynes p-X-C6H4C≡CH (X = OMe, CH3, Cl, F) and the Hammett σp, indicates that the alkyne C-H bond activation step is not rate-limiting.

Figure 1.

Hammett plot for the coupling reaction of m-X-C6H4NH2 (X = OMe, CH3, H, F) with HC≡CCH3 using the catalyst 4/HBF4·OEt2 (3 mol%, 1:3 ratio).

The coupling reaction catalyzed by 1 was found to be strongly inhibited by added phosphines. For example, the addition of 5 mol% of PCy3 under the reaction conditions shown in eq 1 led to <30% of the product 2a after 24 h. The pseudo-first order plots showed that the observed rate constant from the reaction with 5 mol% of added PCy3 (kobs = 4.9 × 10−2 h−1) was found to be nearly three times smaller than the rate under normal conditions (kobs = 1.7 × 10−1 h−1) (Figure S2, Supporting Information). This result suggests that the reactive species is generated from the reversible dissociation of phosphines for the reactions catalyzed by 1.

Deuterium Labeling Study

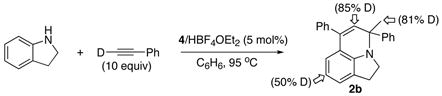

The reaction of indoline with excess DC≡CPh (10 equiv) and 4/NH4PF6 (3 mol%) yielded the product 2b with extensive deuterium incorporation on both vinyl (85%) and methyl (81%) positions as well as on the arene hydrogen para to the amine group (~50%) as measured by both 1H and 2H NMR (eq 3). Conversely, ca. 25% of the methyl group and 30% of the vinyl hydrogen of 2b were found to contain the deuterium when N-deuterated indoline was reacted with 10 equiv of HC≡CPh.

|

(3) |

|

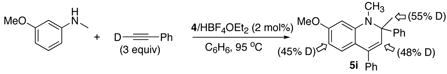

(4) |

|

(5) |

Similar results were obtained from the reactions of acyclic arylamines. For example, the treatment of m-OMe-C6H4NHCH3 with DC≡CPh (3 equiv) gave the product 5i with extensive deuterium incorporation on both α-methyl (55%) and vinyl (48%) as well as on the arene positions (45% combined at C6 and C8) (eq 4). Lower deuterium incorporation was observed to 5i compared to 2b, and this may be in part due to the smaller amount of DC≡CPh than in eq 3 and slower reaction rate for an acylic secondary amine, which might have led to H/D exchange to other arene positions. Conversely, the reaction of m-OMe-C6H4NDCH3 with HC≡CPh (3 equiv) resulted in 5i with significant amounts of deuterium on α-methyl (18%), vinyl (10%) and arene (11%) positions. The similar deuterium incorporation pattern was also observed for one-to-one coupling reaction of N-deuterated 1-(2-amino-1-phenyl)pyrrol with HC≡CPh (1 equiv) (eq 5). In this case, the deuterium was selectively incorporated to the α-methyl group (31%) of 7b without significant exchange to other arene positions. In a control experiment, the treatment of m-OMe-C6H4NHCH3 with DC≡CPh (3 equiv) in the presence of HBF4·OEt2 (6 mol%) under otherwise similar conditions led to <5% of deuterium exchange to the ortho- and para-arene positions of m-OMe-C6H4NHCH3 after 24 h of reaction time at 95 °C, without forming any measurable amount of the product 5i. These results indicate that both the N–H and the acetylenic C–H bond activation steps are reversible.

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

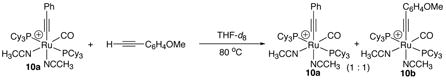

Reactions of the Cationic Ruthenium-Acetylide Complex

We previously detected the formation of cationic ruthenium-acetylide complexes during the catalytic reactions mediated by 1. The cationic ruthenium-acetylide complex [(PCy3)2(CO)(CH3CN)2RuC≡CPh]+BF4− (10a) was subsequently isolated in 81% yield from the reaction of 1 with HC≡CPh in THF, and its structure was established by X-ray crystallography.11 The activity of isolated complex 10a was found to be very similar to that of 1 for the catalytic coupling reactions of both indoline and aniline with terminal alkynes. The isolation of the catalytically active complex 10a enabled us to further examine the reactions that are relevant to the catalysis. For example, the treatment of 10a with HC≡CC6H4-p-OMe (5 equiv) in THF for 3 h at 80 °C produced a ~1:1 mixture of 10a and the alkyne-exchanged complex [(PCy3)2(CO)(CH3CN)2RuC≡CC6H4-p-OMe]+BF4− (10b) (eq 6). Similarly, the reaction of 10a with indoline (1 equiv) and propyne (10 equiv) was monitored by NMR (eq 7). In this case, only the propyne coupling product 2a was formed without any observable amount of the phenyl-substituted product 2-Ph. Both of these results indicate that the alkyne exchange process is relatively facile under the catalytic reaction conditions.

Mechanism of the Catalytic Reaction

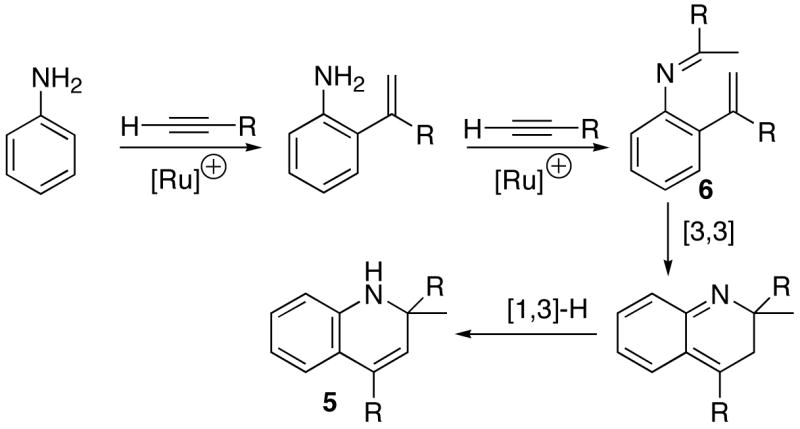

We initially considered a few different mechanistic pathways to explain the formation of C-H bond activation products. One of the possible mechanisms involves a sequential ortho-C-H bond activation and hydroamination reactions as depicted in Scheme 1. The key features of this mechanism are that the ruthenium-mediated ortho-C-H bond insertion of an alkyne to form the ortho-vinylated amine, the hydroamination of the second alkyne and the subsequent electrocyclization to give the product 5. Both hydroamination of alkynes and ortho-C-H bond insertion of arylamines have been well-documented in the literature.1,17

Scheme 1.

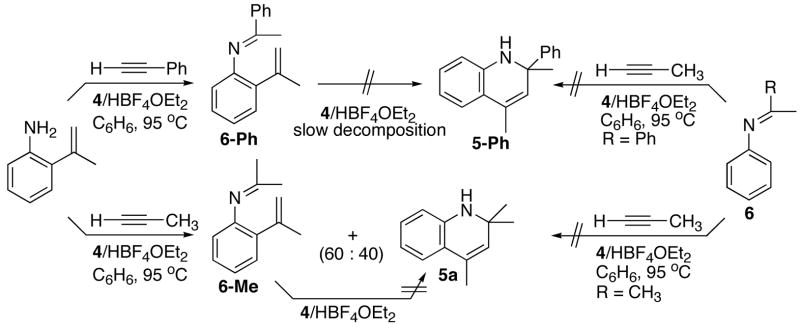

We reasoned that the reaction of independently prepared 2-vinylaniline with terminal alkynes would result the product 5 under the similar catalytic conditions if 2-vinylaniline is an intermediate for the catalytic reaction. We tested this hypothesis by examining the reaction of 2-isopropenylaniline with terminal alkynes (Scheme 2). The hydroamination product 6-Ph was exclusively produced from the reaction of 2-vinylaniline with phenylacetylene under the catalytic conditions, and moreover, 6-Ph was not converted to the cyclized product 5-Ph even after prolonged heating at 95 °C for 48 h. In a separate experiment, the treatment of the independently formed hydroamination product 6b with excess propyne did not give the cyclized product 5-Ph. Though the reaction of independently generated 2-isopropenylaniline with excess propyne resulted in a mixture of products 5a and 6-Me (40 : 60), the hydroamination product 6-Me was not converted to the cyclized product 5a under the reaction conditions. The treatment of 6a with excess propyne did not give the product 5-Ph, either. The similar [3,3]-electrocyclic reactions are often conducted under strongly acidic conditions at elevated temperature,18 and we believe that HBF4 might have acted as an acid catalyst in forming the cyclization product 5a in the case of propyne. Since the formation of hydroamination product 6 is generally much favored over the ortho-C-H bond insertion product 5 for the reaction of arylamines with alkynes and that 6 does not convert to the cyclized product 5, 2-isopropenylaniline cannot be a viable intermediate for the catalytic reaction. Uchimaru also reported that the reaction of arylamines with alkynes predominantly formed the hydroamination product over the ortho-C-H bond activation product.13b Taken these results together, we ruled out the sequential mechanism of ortho-vinylation and hydroamination of alkynes for the catalytic reaction.

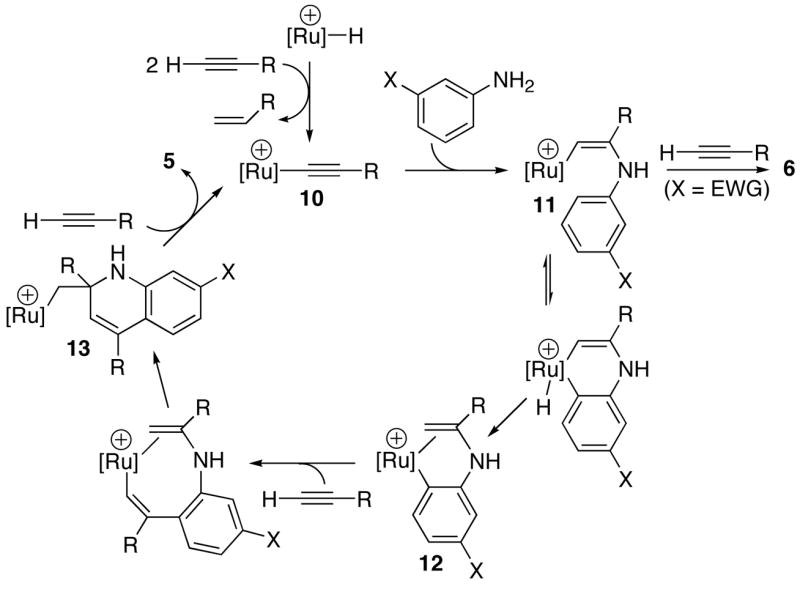

Scheme 2.

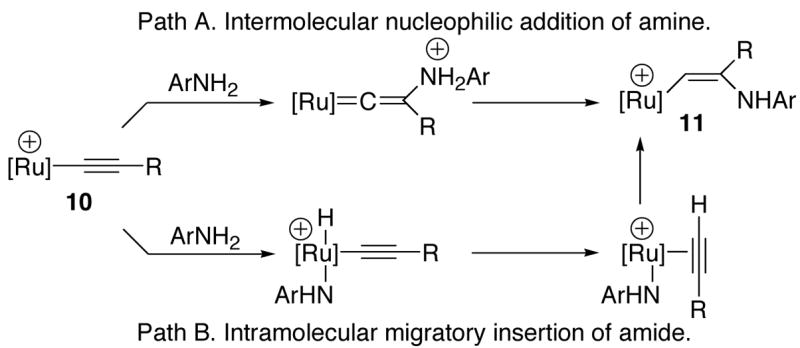

The observed data are consistent with a mechanism involving an unsaturated cationic ruthenium–acetylide complex 10 as the key species (Scheme 3). We previously showed that the catalytically active acetylide species 10a is generated during the reactions catalyzed by the cationic hydride complex 1. Two possible mechanistic pathways can be considered for the C-N bond forming step from 10, an intermolecular nucleophilic addition vs an intramolecular migratory insertion mechanism (Scheme 4), both of which would lead to the cationic enaminyl species 11. The subsequent ortho-arene C-H bond activation and the reductive elimination of vinyl group would form the ortho-metallated species 12. The fact that extensive deuterium incorporation to aryl positions on the product 5 can be rationalized by the formation of meta- and para-metallated species from reversible arene-C-H bond activation steps, of which the enamine-coordinated ortho-metallated species would lead to the product formation. Furthermore, the results from the deuterium labeling studies indicate that the arene C-H bond activation step is reversible as shown in Scheme 3. Both the normal isotope effect of kCH/kCD and a highly negative Hammett ρ value are consistent with the arene C–H bond activation rate–limiting step. The negative ρ value also suggests the formation of cationic ruthenium-aryl species during the arene ortho-C–H bond activation step. The second alkyne insertion and the regioselective migratory insertion/cyclization steps would yield the cationic alkyl species 13. Since 13 does not have any β-hydrogens, either the oxidative addition/reductive elimination or the σ-bond metathesis of the terminal alkyne must be invoked for the formation of 5 and the regeneration of the acetylide complex 10. For arylamines with a meta-electron-withdrawing group, the predominant formation of hydroamination product 6 can be readily rationalized by the preferential oxidative addition/reductive elimination of another terminal alkyne from 11. Site–selective C–H activation and functionalization reactions by trimetallic Ru3(CO)12 have been observed for a number of different catalytic reactions.19

Scheme 3.

Scheme 4.

Two different pathways have been commonly proposed for the hydroamination reactions. For example, Hartwig provided strong evidence for an intermolecular nucleophilic addition mechanism for the Pd-catalyzed hydroamination of aryl-substituted alkenes.20 Both concerted and stepwise intramolecular migratory insertion mechanisms via metal-amido complexes have been commonly proposed for early transition and lanthanide metal-mediated hydroamination reactions.21 In our case, intermolecular nucleophilic addition of amine to the β-acetylide carbon and the subsequent proton transfer would form the enaminyl intermediate 11 (Scheme 4, Path A). Alternatively, the formation of an alkyne-coordinated amido complex (from initial N-H bond activation and the hydrogen transfer to the acetylide ligand) and the intramolecular migratory insertion of the amido group should lead to the same enaminyl intermediate 11 (Path B).

We envisioned a crossover experiment to probe between inter- vs intramolecular mechanistic pathways for the C-N bond-forming step (Scheme S1, Supporting Information). We reasoned that the amount of deuterium atoms at the α-methyl positions reaction of an arylamine with a 1:1 mixture of DC≡CPh and HC≡CC6H4-p-OMe would be significantly different for the inter- vs intramolecular mechanisms. According to the intermolecular nucleophilic addition mechanism, an equal amount of deuterium (17%) is expected to be incorporated to both α-CH3 groups of the products from the statistical H/D distribution of the alkyne C-H bond to the products (Scheme S1, Path A). The sequential mechanism as described in Scheme 1 would also result in a similar deuterium incorporation pattern. In contrast, the intramolecular migratory insertion mechanism is expected to give the products with a substantially higher deuterium incorporation to the α-CH3 of the phenyl-substituted product (50%) compared to that of p-OMe-C6H4-substituted product (17%), if one assumes a rapid and reversible alkyne substrate exchange and the subsequent statistical H/D distribution from alkyne C-H bond oxidation/reductive elimination steps (Scheme S1, Path B).

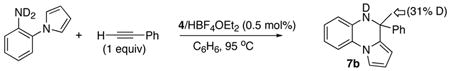

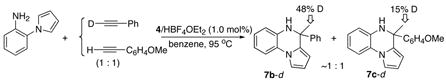

|

(8) |

Initial reaction survey for both indoline and meta-substituted aniline with a mixture of two different alkynes produced a complex mixture of both homo- and cross-coupling products. To simplify the product analysis, pyrrol-substituted aniline was employed since it incorporates only one equivalent of terminal alkyne per molecule of amine. Thus, the treatment of 1-(2-aminophenyl)pyrrole (1.9 mmol) with a 1:1 mixture of DC≡CPh and HC≡CC6H4-p-OMe (1 equiv each) in the presence of the catalyst 4/HBF4·OEt2 (1 mol%) at 95 °C in benzene solution produced ~1:1 mixture of 7b–d and 7c–d after 24 h (eq 8). The products were separated by a simple column chromatography on silica gel, and the deuterium content of the products was analyzed by both 1H and 2H NMR. The NMR analysis clearly showed substantially higher deuterium incorporation on the α-CH3 group of 7b–d (48%) compared to that of 7c–d (15%). In a control experiment, the reaction in the absence of the ruthenium catalyst 4 neither resulted in any significant H/D exchange between DC≡CPh and HC≡CC6H4-p-OMe nor gave any measurable products 7. Thus, the observed deuterium incorporation pattern must have occurred during the catalytic reaction, and provides a strong evidence for the intramolecular migratory insertion mechanism.

Conclusion

A new catalytic C-H bond activation/cyclization protocol has been developed for the synthesis for quinoline and quinoxaline derivatives. The mechanistic data are consistent with the mechanism involving an intramolecular migratory insertion of amine and the subsequent ortho-C-H bond activation and cyclization via an unsaturated cationic ruthenium-acetylide complex. The catalytic C-H bond activation/cyclization method should find a range of new applications for the synthesis of quinoline and other nitrogen heterocyclic compounds.

Experimental Section

General Information

All operations were carried out in a nitrogen-filled glove box or by using standard high vacuum and Schlenk techniques unless otherwise noted. Tetrahydrofuran, benzene, hexanes and Et2O were distilled from purple solutions of sodium and benzophenone immediately prior to use. The NMR solvents were dried from activated molecular sieves (4 Å). All amine and alkyne substrates were received from commercial sources and used without further purification. RuCl3·3H2O and Ru3(CO)12 were obtained from commercial sources, and the complex 1 was prepared by following a reported procedure.22 The 1H, 13C and 31P NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury 300 MHz FT-NMR spectrometer. Mass spectra were recorded from a Hewlett-Packard HP 5970 GC/MS spectrometer. High-resolution FAB mass spectra were obtained at the Center of Mass Spectrometry, Washington University, St. Louis, MO. Elemental analyses were performed at the Midwest Microlab, Indianapolis, IN.

Isotope Effect Study

In a glove box, an equal amount of C6H5NH2 and C6D5NH2 (0.4 mmol, 37 μL) was added via a syringe to two separate 25 mL Schlenk tubes. Predissolved Ru3(CO)12 (8 mg, 3 mol %) in benzene solution (3 mL) was added to each Schlenk tubes. The reaction tubes were brought out of the box and HBF4·OEt2 (8 μL, 9 mol % based on amine) was added to each tube under a nitrogen stream. The reaction tubes were cooled in a liquid nitrogen bath, and excess propyne (2 mmol) was condensed into each tube via a vacuum line transfer. The reaction tubes were warmed to room temperature, and stirred in an oil bath at 95 °C. A small portion of the aliquot under a nitrogen stream was drawn periodically from the reaction tube, and the product conversion was determined by GC.

Hammett Study

In a glove box, meta-substituted aniline m-X-C6H4NH2 (X = OMe, CH3, H, F) (0.54 mmol), Ru3(CO)12 (10 mg, 0.016 mmol) and benzene (3 mL) were added to each of four separate 25 mL Schlenk tubes equipped with a stirring bar. The reaction tubes were brought out of the box, and HBF4·OEt2 (10 μL, 9 mol % based on amine) was added to each tube under a nitrogen stream. The reaction tubes were cooled in a liquid nitrogen bath, and excess propyne (2 mmol) was condensed into each tube via a vacuum line transfer. The reaction tubes were warmed to room temperature, and stirred in an oil bath at 95 °C. A small portion of the aliquot under a nitrogen stream was drawn periodically from each reaction tube. The kobs was determined from a first-order plot of ln[5] vs time as measured by the appearance of the product 5 by GC.

Representative Procedure of Deuterium Labeling Study: Reaction of m-OMe-C6H4NHCH3 with DC≡CPh

In a glove box, m-OMe-C6H4NHCH3 (300 mg, 2.2 mmol), DC≡CPh (676 mg, 6.6 mmol), Ru3(CO)12 (28 mg, 43 μmol) were dissolved in 5 mL benzene in a 25 mL Schlenk tube equipped with a magnetic stirring bar. The reaction tube was brought out of the box, and HBF4·OEt2 (28 μL, 3 equiv based on Ru) was added via a microsyringe under a stream of nitrogen. The reaction tube was stirred in an oil bath at 95 °C for 24 h. The solvent was removed from a rotary evaporator, and the organic product was isolated by a column chromatography on silica gel (hexane/CH2Cl2 = 3:2). The deuterium content of the product 5i was measured by both 1H NMR (CDCl3 and cyclohexane (10 mg, external standard)) and 2H NMR (CH2Cl2 and CDCl3 (0.05 mL)).

Crossover Experiment

In a glove box, 1-(2-aminophenyl)pyrrole (300 mg, 1.9 mmol), DC≡CPh (196 mg, 1.9 mmol), HC≡C-C6H4-p-OMe (250 mg, 1.9 mmol) and Ru3(CO)12 (0.012 mg, 0.019 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL benzene in a thick-walled 25 mL Schlenk tube equipped with a magnetic stirring bar. The reaction tube was brought out of the box, and HBF4·OEt2 (3 eq based on ruthenium) was added via a microsyringe under a stream of nitrogen. The reaction tube was stirred in an oil bath at 95 °C for 24 h. The solvent was removed from a rotary aspirator, and the organic products 7b and 7c were isolated by a column chromatography on silica gel (hexane/CH2Cl2 = 1:1). The deuterium content of each product was measured by both 1H NMR (CDCl3, cyclohexane as an external standard) and 2H NMR (CH2Cl2 and 0.05 mL of CDCl3).

Phosphine Inhibition Study

In a glove box, complex 1 (36 mg, 5 mol %), PCy3 (12 mg, 5 mol %) and indoline (100 mg, 0.8 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL of benzene in a thick-walled 25 mL Schlenk tube equipped with a magnetic stirring bar. The reaction tube was brought out of the box, and cooled in a liquid nitrogen bath. Excess propyne (20 mmol) was condensed into the tube via a vacuum line transfer. The reaction tube was warmed to room temperature, and stirred in an oil bath at 95 °C. A small portion of the aliquot was drawn periodically from the reaction mixture under a nitrogen stream, and the product conversion was determined by GC.

General Procedure of the Catalytic Reaction

In a glove box, an amine (1–2 mmol), a terminal alkyne (5–10 mmol) and Ru3(CO)12 (10–50 mg, 1–5 mol %) were dissolved in 5 mL benzene in a thick-walled 25 mL Schlenk tube equipped with a magnetic stirring bar. The reaction tube was brought out of the box, and HBF4·OEt2 (10–50 μL, 3 equiv based on Ru) was added via a microsyringe under a stream of nitrogen. The vacuum-line technique was used to transfer volatile alkynes such as propyne and 1-butyne. The reaction tube was stirred in an oil bath at 95 °C for 16–24 h. The tube was opened to air at room temperature, and the crude product mixture was analyzed by GC. The solvent was removed from a rotary evaporator, and the organic product was isolated by a column chromatography on silica gel (hexane/CH2Cl2).

Supplementary Material

Spectroscopic data of organic compounds (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http//:pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Institute of Health, General Medical Sciences (R15 GM55987) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Recent reviews: Kakiuchi F, Murai S. In: Activation of Unreactive Bonds and Organic Synthesis. Murai S, editor. Springer; New York: 1999. Jia C, Kitamura T, Fujiwara Y. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:633. doi: 10.1021/ar000209h.Ritleng V, Sirlin C, Pfeffer M. Chem Rev. 2002;102:1731. doi: 10.1021/cr0104330.

- 2.(a) Tan KL, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2685. doi: 10.1021/ja0058738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thalji RK, Ahrendt KA, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9692. doi: 10.1021/ja016642j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Zhang X, Fried A, Knapp S, Goldman AS. Chem Commun. 2003:2060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kakiuchi F, Tsuchiya K, Matsumoto M, Mizushima E, Chatani N. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12792. doi: 10.1021/ja047040d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sezen B, Sames D. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5284. doi: 10.1021/ja0699586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhang X, Emge TJ, Ghosh R, Goldman AS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8250. doi: 10.1021/ja051300p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Chatani N, Asaumi T, Yorimitsu S, Ikeda T, Kakiuchi F, Murai S. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10935. doi: 10.1021/ja011540e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kakiuchi F, Murai S. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:826. doi: 10.1021/ar960318p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Dangel BD, Godula K, Youn SW, Sezen B, Sames D. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11856. doi: 10.1021/ja027311p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sezen B, Franz R, Sames D. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13372. doi: 10.1021/ja027891q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Sezen B, Sames D. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13244. doi: 10.1021/ja069957d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dick AR, Hull KL, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2300. doi: 10.1021/ja031543m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li Z, Li CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6968. doi: 10.1021/ja0516054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kalyani D, Deprez NR, Desai LV, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:7330. doi: 10.1021/ja051402f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Daugulis O, Zaitsev VG. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:4046. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Ferreira EM, Stoltz BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9578. doi: 10.1021/ja035054y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Campo MA, Huang Q, Yao T, Tian Q, Larock RC. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11506. doi: 10.1021/ja035121o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu C, Han X, Wang X, Widenhoefer RA. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3700. doi: 10.1021/ja031814t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) DeBoef B, Pastine SJ, Sames D. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6557. doi: 10.1021/ja049111e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Liu C, Widenhoefer RA. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10250. doi: 10.1021/ja046810i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Espino CG, Fiori KW, Kim M, Du Bois J. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15378. doi: 10.1021/ja0446294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Davies HML, Long MS. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:3518. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Nobis M, Drieβen-Hölscher B. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:3938. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fulton JR, Holland AW, Fox DJ, Bergman RG. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:137. doi: 10.1021/ar000132x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fulton JR, Sklenak S, Bouwkamp MW, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4722. doi: 10.1021/ja011876o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Conner D, Jayaprakash KN, Cundari TR, Gunnoe TB. Organometallics. 2004;23:2724. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Yi CS, Yun SY, He Z. Organometallics. 2003;22:3031. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yi CS, Yun SY, Guzei IA. Organometallics. 2004;23:5392. [Google Scholar]; (c) Yi CS, Yun SY. Org Lett. 2005;7:2181. doi: 10.1021/ol050524+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yi CS, Yun SY, Guzei IA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5782. doi: 10.1021/ja042318n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.See the Supporting Information (Table S1) for a representative example.

- 13.(a) Tokunaga M, Eckert M, Wakatsuki Y. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1999;38:3222. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19991102)38:21<3222::aid-anie3222>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Uchimaru Y. Chem Commun. 1999:1133. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selected recent examples: Myers AG, Tom NJ, Fraley ME, Cohen SB, Madar DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6072.Takamura M, Funabashi K, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6801. doi: 10.1021/ja010654n.Ku YY, Grieme T, Raje P, Sharma P, King SA, Morton HE. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4282. doi: 10.1021/ja0171198.Ori M, Toda N, Takami K, Tago K, Kogen H. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:2540. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351069.Back TG, Wulff JE. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:6493. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461327.

- 15.(a) Seitz LE, Suling WJ, Reynolds RC. J Med Chem. 2002;45:5604. doi: 10.1021/jm020310n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nair V, Dhanya R, Rajesh C, Bhadbhade MM, Manoj K. Org Lett. 2004;6:4743. doi: 10.1021/ol048004m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen BC, Zhao R, Bednarz MS, Wang B, Sundeen JE, Barrish JC. J Org Chem. 2004;69:977. doi: 10.1021/jo0355348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Jaso A, Zarranz B, Aldana I, Monge A. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2019. doi: 10.1021/jm049952w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carey FA, Sundberg RJ. Advanced Organic Chemistry Part A: Structure and Mechanism. 3. Plenum Press; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Brunet JJ, Neibecker D. In: Catalytic Heterofunctionalization from Hydroamination to Hydrozirconation. Togni A, Grützmacher H, editors. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]; (b) Roesky PW, Müller TE. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:2708. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Hiemstra H, Speckamp WWN. Ch. 4.5 In: Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Vol. 5. Pergamon; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cook GR, Barta NS, Stille JR. J Org Chem. 1992;57:461. [Google Scholar]; (c) Shiraishi K, Rajca A, Pink M, Rajca S. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9312. doi: 10.1021/ja051521v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Fukuyama T, Chatani N, Tatsumi J, Kakiuchi F, Murai S. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:11522. [Google Scholar]; (b) Godula K, Sezen B, Sames D. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3648. doi: 10.1021/ja042510p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Löber O, Kawatsura M, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4366. doi: 10.1021/ja005881o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nettekoven U, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1166. doi: 10.1021/ja017521m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hartwig JF. Pure Appl Chem. 2004;76:507. [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Tian S, Arredondo VM, Stern CL, Marks TJ. Organometallics. 1999;18:2568. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hong S, Tian S, Metz MV, Marks TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14768. doi: 10.1021/ja0364672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ryu J-S, Li GY, Marks TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12584. doi: 10.1021/ja035867m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi CS, He Z, Guzei IA. Organometallics. 2001;20:3641. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Spectroscopic data of organic compounds (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http//:pubs.acs.org.