Abstract

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is an approach to scientific research that is gaining broader application to address persistent problems in health care disparities and other hypothesis-driven research. However, information on how to form CBPR community-academic partnerships and how to best involve community partners in scientific research is not well-defined. The purpose of this paper is to share the experience of the Partnership for Improving Lifestyle Interventions (PILI) `Ohana Project in forming a co-equal CBPR community-academic partnership that involved 5 different community partners in a scientific research study to address obesity disparities in Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Peoples (i.e., Samoans, Chuukese, and Filipinos). Specifically, the paper discusses 1) the formation of our community-academic partnership including identification of the research topic; 2) the development of the CBPR infrastructure to foster a sustainable co-equal research environment; and 3) the collaboration in designing a community-based and community-led intervention. The paper concludes with a brief summary of the authors' thoughts about CBPR partnerships from both the academic and community perspectives.

Introduction

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is an approach to scientific inquiry that “equitably involves all partners [community and academic] in the research process and recognizes the unique strengths that each brings.”1 Despite variations in practice,2 CBPR is becoming more widely accepted in a wide range of contexts and among ethnically diverse communities as an approach for addressing persistent problems in health care disparities and other types of health research.3 As community-based organizations serving Native Hawaiians (NHs) and other Pacific Island Peoples (PIPs) delve deeper into translational research (e.g., effectiveness and dissemination studies), the need for academic-community partnerships that aim to achieve balance between scientific rigor and community wisdom emerges. Although there are many publications on the principles, approaches, and benefits of CBPR,2,4,5 little is known about how to form sustainable CBPR community-academic partnerships as a means to address health disparities particularly in NH and PIP communities. The purpose of this paper is to share the process undertaken and the insights learned by the Partnership for Improving Lifestyle Interventions (PILI) `Ohana Project (Pili is relationship and `Ohana is family in the Hawaiian language) in forming a co-equal CBPR community-academic partnership that involved 5 community partners in a scientific research study to address obesity disparities in NH and other PIP (i.e., Samoans, Chuukese, and Filipinos).

Forming a Community-Academic Partnership

Researchers from the Department of Native Hawaiian Health (DNHH) began the forging of a CBPR partnership by inviting 10 community-based organizations serving NH and other PIP to discuss the top health concerns of their respective communities. These 10 community-based organizations ranged from community health centers to long-standing civic clubs to grassroots community organizations, but all had a prior relationship with the DNHH through the Ulu Community Network of the Hawai`i EXPORT Center (HEC) and had expressed an interest in participating in research. The Ulu Network is a community network of 21 organizations and agencies who serve NH and other PIP throughout the state of Hawai'i and was formed in 2000 as part of the Community Engagement Core of the HEC, whose mission is to reduce and eliminate health disparities via research, training and community engagement.

The initial discussions between DNHH researchers and the 10 community-based organizations were facilitated by a number of experienced CBPR academic leaders including the Director of the Ulu Network and the Director of the HEC who laid the foundation for power sharing and fostering a respectful, collaborative relationship in keeping with the spirit of CBPR.1-2 At the first meeting, the top 3 health concerns of the 10 community organizations were discussed to determine possible interventions, the formation of a formal CBPR partnership, and the potential roles of the partners (communities and academic). Obesity was collaboratively identified as a major concern and high priority health issue by all 10 community organizations. Due to other priorities and commitments, 5 of the 10 original community organizations chose to serve in an active role in a CBPR partnership at the time, while the other 5 agreed to serve in an advisory role. The 5 self-selected community organizations and the academic partner (the DNHH) discussed further who should serve as the lead organization to coordinate and submit the grant proposal on behalf of the newly formed CBPR partnership to the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The DNHH was nominated to carry out this responsibility.

The name PILI `Ohana Project was discussed and unanimously approved by the CBPR partnership and exemplifies the mission of the partnership – to bring the communities together to eliminate obesity disparities in Hawai`i. The 5 community partners of the PILI `Ohana Project represent 3 different types of community organizations: 1) Grassroots organizations, 2) Native Hawaiian Health Care System, and 3) Community Health Centers. The strengths of each partner are briefly described here:

Grassroots organizations (GRO)

Hawai`i Maoli - The Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs (HM-AHCC) and Kula No NāPo`e Hawai`i (KNNPH) represent 2 GROs. HM-AHCC is the oldest private, non-profit, community-based Native Hawaiian organization comprised of a confederation of 54 clubs with a collective membership of over 2,800 individuals located throughout the states of Hawai`i, Alaska, California, Colorado, and Nevada. Recently the Association has turned its attention to issues of health and wellness with the recognition that its members are disproportionately affected by chronic illnesses.

KNNPH is also a non-profit organization, formed in 1992 by a group of concerned community women to help improve the educational skills of children from the NH Homestead communities of Papakālea, Kewalo, and Kalawahine located in urban Honolulu. The educational vision of KNNPH has broadened to include activities that raise the awareness of good health, nutrition, and exercise. In 2003, they implemented health screening for diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular risk factors and health education counseling.

Community Health Centers (CHC)

Kalihi-Pālama Health Center (KPHC) and Kōkua Kalihi Valley Comprehensive Family Services (KKV) represent the two CHCs. KPHC is a private non-profit CHC that provides primary care services to many PIPs (i.e. Micronesians and Filpinos). KPHC is committed to addressing obesity-related disparities such as diabetes and has implemented a diabetes management program, weekly diabetes clinics, and a diabetes support group tailored to their multi-ethnic population.

KKV is a community-owned and operated non-profit corporation formed in 1972 by community and church leaders to address the lack of adequate and accessible health services in their community. Health services are provided to a primarily low-income PIP population (i.e. Micronesian, Samoan, and other immigrant groups) and include a wide range of services such as dental, medical, and mental health. KKV has implemented community gardening and diabetes education programs at their CHC and employs an ethnically diverse staff that is fluent in 17 Asian and Pacific Island languages.

Native Hawaiian Health Care System (NHHCS)

Ke Ola Mamo (KOM) is a private, non-profit NHHCS for the island of O`ahu. KOM has 4 locations and provides services to primarily low income NHs and their families that include community outreach, transportation assistance, health education and prevention/wellness programs. KOM has more than 10 years of experience conducting health screenings and implementing health education programs such as the nationally recognized Diabetes Mellitus Awareness Program.

Academic Partner

The DNHH is a University of Hawai`i, Board of Regents approved clinical department of the John A. Burns School of Medicine that was formed in 1999 and consists of 4 cores: 1) Administrative, 2) Clinical Teaching and Health Care Services, 3) Medical Education, and 4) Research and Evaluation. Collectively, the DNHH research leadership has 10+ years of NIH-funded research experience in epidemiological, observational, intervention development, program evaluation, and clinical trials research addressing multiple health disparity topics such as diabetes,6 cardiovascular disease,7 chronic kidney disease, and health behaviors.8

Thus, each of the academic and community organizations brought into the CBPR partnership a wealth of experience and community wisdom in serving and working with NH and PIP in Hawai`i via various capacities – from clinical services to social advocacy.

In particular, 2 key elements about the formation of the CBPR partnership were important in developing trust. First, the partnership began with community organizations and academic researchers who collaborated previously and already demonstrated an interest in research. Prior relationships with the members of a CBPR community-academic partnership are helpful as academic researchers must consider the communities' attitudes towards scientific research, particularly the tendency towards mistrust of the academic researchers and their intentions. Similarly, community organizations need to weigh the benefits (e.g., having an effective community-based intervention) and risks (e.g., expenditure of the community resources) of participating in scientific research to their respective communities.

Second, as mentioned previously, communities can be defined in a number of different ways. In the formation of this CBPR partnership, the primary interest was organizations with a significant burden of obesity health disparities in the communities they served (i.e. NH and other PIP), and all of the community organizations involved provided services primarily to these populations.

Establishing a CBPR Infrastructure

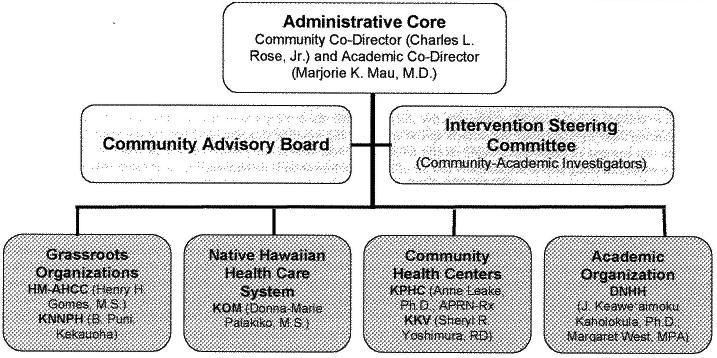

The CBPR administrative infrastructure established by the PILI `Ohana Project is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The PILI `Ohana Project's CBPR infrastructure including the community and academic investigators

To ensure a balance of power among all partners (community and academic), an Administrative Core consisting of 2 co-equal leadership positions entitled the Community Director and the Academic Director were created. A Community Advisory Board (CAB) was formed to provide guidance on maintaining the partnership and establishing CBPR policies, and consisted of members from the 5 partnering communities as well as the 5 community organizations initially involved in the planning process. An Intervention Steering Committee (ISC) was also formed, which consisted of all partners (5 communities and 1 academic) who would meet monthly to discuss the development, implementation, and evaluation of all research activities and continuous assessment of the CBPR partnership.

The first undertaking of the ISC was the creation of a document that informs and guides the partnership in maintaining a co-equal and mutually respectful research environment. This document entitled the “PILI `Ohana Project Principle and Guidelines for Overall Governance” documents: (1) purpose, (2) CBPR principles and values, (3) roles and responsibilities of each partner, (4) decision making process, (5) handling and sharing of data, (6) evaluation process of the CBPR partnership, and (7) procedures to amend the document. The establishment of the infrastructure and guiding principles and guidelines was invaluable in providing a framework for day-to-day operations, providing a mechanism to address a myriad of concerns or disputes, and demonstrating the commitment of each partnering organization to the CBPR process, especially the commitment of the academic partner to include the community organizations as co-equal CBPR partners.

Design of a Research Study

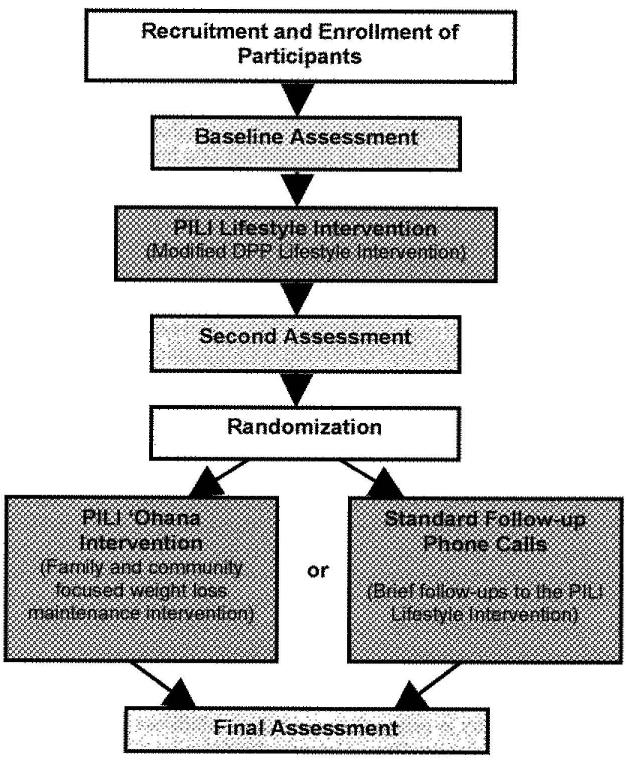

Through a series of meetings facilitated by the Community and Academic Co-Directors, the community-academic partnership negotiated a mutually acceptable research design and protocol that engaged the community partners as well as maintained scientific rigor. The PILI `Ohana Project partners struggled with the scientific perspective and experimental design issues, such as using a randomized controlled trial (RCT) protocol, in which participants are randomly assigned to either the intervention being evaluated or to a control group. From the community perspective, intervention needed to ensure that no participant was denied or delayed in receiving a possibly effective intervention. In balancing these 2 perspectives, the partners agreed upon a RCT design that ensured all participants would receive an active intervention while still being able to scientifically test the efficacy of the weight loss maintenance intervention. The basic research design is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

PILI `Ohana Project's Basic Research Design

It was agreed by all CBPR partners that all study participants would receive a culturally adapted version of the Diabetes Prevention Program's (DPP) Lifestyle Intervention.9 After completing the intervention, participants would be randomized to either a family-and community-focused intervention (a new intervention designed by the PILI partnership) for weight loss maintenance or to a control group (standard phone-call follow-ups only). In this way, all study participants would be able to receive an intervention which was modified to be used in these populations and found to be efficacious as well as participate in the hypothesis-testing portion of the study to evaluate a weight loss maintenance intervention via an RCT.

The final step was negotiating the roles and responsibilities of each partner in conducting the planned research activities. To build the communities' capacity to engage in research and deliver community-based interventions, it was collectively decided that all the interventions would be delivered, and all data maintained, by community-peer educators and staff from each of the 5 community sites. The DNHH would provide and standardize research training, technical assistance, and collate the de-identified data from each community organization for overall study analyses.

Reflections on the CBPR Partnership

Although the CBPR approach experiences of the PILI `Ohana Project may not be generalizable to all CBPR projects, the collective experience of this project demonstrates that CBPR approaches can provide a framework for engaging the community while maintaining scientific merit and offer hope for ensuring that populations with a disproportionate burden of health disparities become active partners in reversing these health disparities and improving the health of their communities and the larger public.

Academic Partners' Experience and Perspective

Most academic investigators engage in a CBPR partnership with community organizations that are similar in function (e.g., direct services) or type (e.g., civic clubs). The diversity in this CBPR partnership added a layer of complexity because 5 different community perspectives with varying skill sets and priorities needed to be considered and balanced throughout the project. Thus, the choice to engage in CBPR significantly added to the time commitment needed and complexity involved in carrying out the research. For example, more meetings are needed to negotiate research ideas and address the diversity in perspectives and values, which can pose challenges to meeting deadlines. However, the richness of ideas and perspectives shared by and long-term relationship fostered with community people through CBPR adds enduring value and meaning to a scientific research project.

In this CBPR partnership, the community partners were completely and equally (e.g., individual budget management) involved in all aspects of the research project, which a paucity of projects is able to do in practice. As shared earlier, the community partners identified the research topic and provided input into how the CBPR partnership would be structured and how the study would be designed and implemented. They also own their own data and determine how the information is disseminated in their respective communities. The active involvement of communities for which the research findings are to benefit is vital to developing effective and sustainable community engaged interventions to eliminate health disparities.

Notwithstanding the many benefits of CBPR, there were challenges in implementing the intervention and assessment protocols. One challenge involved the standardization of research protocols and the adherence to these protocols across the 5 different community partners. Scientific investigations, like RCTs, seek to reduce or eliminate biases most often through strict adherence to standardized research and intervention protocols. Despite having standardized protocols in the RCT, it was challenging to maintain consistency and adherence to the protocols across 5 community settings with very different organizational structures. For example, due to the community partners' multiple responsibilities and competing demands, certain parts of the intervention and assessment protocols were difficult to adhere to, such as having the same community-peer educator delivering the intervention or having the required number of assessors available at all times. Another example is variations in the delivery of intervention materials because of differences among community-peer educators in expertise and familiarity with facilitating groups, as well as dissimilarities across bilingual translators in the translation of materials into different Pacific Islander languages. However, the challenges faced by the community partners reminded the group that these are real-world issues, and if interventions are to be effective (vs. efficacious) and transportable across settings, they need to withstand many of these real-world challenges.

Community Partners' Collective Experience and Perspectives

For the 5 community partners, the primary purpose for engaging in a CBPR initiative was to build capacity and resources to engage in future health disparities research, and sustain the programs and services developed in their respective communities, both independently and with academic partners. Communities are no longer accepting roles that minimize their abilities in research studies. The 5 community partners in the PILI `Ohana Project had a fundamental commitment to contribute to research in a meaningful manner, and as a result, became key stakeholders in the design and implementation of this research project. Despite the experiences of the PILI `Ohana Project's 5 communities, there still were some critics, both community and academic, who questioned the motives of researchers and also whether community groups have the capacity to participate in research projects as equal partners. The CBPR approach undertaken by the PILI `Ohana partnership encouraged the communities to actively contribute to the research process from developing the research question to how the research is conducted, managed, and eventually, interpreted and disseminated in their respective communities.

Evident in the CBPR approach used throughout this project was the sharing of power that was evident in study resources as well as decision making and an established understanding of unrestricted exchange of knowledge and expertise. This multi-relationship dynamic involved not only community and academic partners but also involved community-to-community relationships. Although this was the first time that 4 of the 5 community partners were involved in an RCT, the community groups were continuously asked for their feedback and suggestions, and were never excluded from the conversation or decision-making process to improve not only the study implementation but also the CBPR process throughout the entire project. In fact, the 5 community partners felt they had more of a vested interest in this project because of the co-sharing of resources and the sense that for the project to succeed all had to succeed individually. Involvement in a co-sharing and co-learning partnership also resulted in the communities' willingness to participate in and work hard to achieve the goals of the research project. For all the community partners, the knowledge acquired and shared became intellectually, physically, personally enriching, and relevant to everyone involved.10

All 5 community partners faced similar challenges around the recruitment and retention of participants from their respective communities. The recruitment of participants took longer than expected, but there was an increase in recruitment and retention rates among participants who were already active in other programs or services offered by the community organizations. Most of the community partners found that participants with pre-existing service-providing relationships (i.e., church and family groups) with the community organizations were more likely to participate and remain in the study than those who had no pre-existing relationship. The other community partners found that the PILI `Ohana Project allowed the opportunity to reach others who were in need of services, but had never visited their community organizations.

Because of their involvement in the PILI `Ohana Project, the community partners have been enabled to seek more creative and innovative paths that can be used to continue programs and services that improve health outcomes for their communities separate from this specific research project. All 5 community partners now have more staff who are familiar with research skills (i.e. research development, implementation, and outcome data collection), which may be helpful with future community research and service projects. The transferablity of knowledge and opportunity to build the reputation of their organizations heightened the communities' regard for the integrity and accountability of their work. Each organization has staff who feel they increased their professional capacity in a manner that would allow them to participate in or implement other research projects. Despite the challenges endured, all the communities are confident that the PILI `Ohana Project has the key components for a successful and sustainable CBPR partnership.

Conclusion

The intention of this article was to share the learned experiences of all partners in the PILI `Ohana Project in forming a CBPR community-academic partnership and to describe the extent of the communities' involvement in the major aspects (i.e., research focus, design and methods, and implementation of research protocols) of a scientific research project. It is the authors' hope that the reflections and collective experiences provided offer some insight into forming and sustaining CBPR partnerships to others who are seeking an opportunity to work with the diverse communities in Hawai'i and elsewhere in the Pacific to eliminate health disparities. In keeping with the spirit of CBPR, this article was conceived and written with meaningful and ongoing involvement from all partners, both academic and community.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the Native Hawaiian, Filipino, Samoan, and Chuukese people of O`ahu and Maui who have participated in the PILI `Ohana Project. We also would like to thank the staff and administration of the five partnering community organizations of Hawai`i Maoli – The Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs, Ke Ola Mamo, Kula no nā Po'e Hawai`i, Kalihi-Pālama Health Center, and Kōkua Kalihi Valley Comprehensive Family Services for their support of this project. The investigators and staff of the PILI `Ohana Project are as follow: Marjorie Mau, M.D. (Principal Investigator and Academic Co-Director) and Charles Rose (Community Co-Director); Henry Gomes, MS, Sheryl R. Yoshimura, RD, Anne Leake, PhD, APRN-Rx, B. Puni Kekauoha, Adrienne Dillard, Donna Palakiko, RN, MS (community investigators); Andrea Siu., BA, JoHsi Wang, Andrea Macabeo, Alohanani Jamais, OTD candidate, Keali`i Lum, OTD candidate, and Melaia Patu (community coordinators and staff); Joseph Keawe`aimoku Kaholokula, PhD, Margaret West, MPH, Andrea Nacapoy, MA, Hanalei Abbott, Sean Mosier, BA, Sheri Kent, Jimmy Thomas Efird, PhD, Pollie Bith-Melander, PhD, Chieko Kimata, RN, MPH and Ka`ohimanu Dang, BA (academic investigators and staff). Finally, we would like to express our gratitude to Kaimi Sinclair, PhD, Erin Saito, PhD, Kanani Texeira, MD for reviewing drafts of this article.

This research was supported in part by awards from the National Center of Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health Grant R24 MD001-660.

References

- 1.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Introduction to community based participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community Based Participatory Research for Health. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; San Francisco, Calif: 2003. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville (MD): Aug, 2004. (Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 99). Summary. AHRQ Pub: 04-E022-1. Contract No. Sponsored by RTI-University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tse AM, Palakiko DM. Participatory Research Manual for Community Partners. Island Heritage Publishing; Waipahu, HI: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mau MK, West MR, Shara NM, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical factors associated with chronic kidney disease among Asian Americans and Native Hawaiians. Ethn Health. 2007;12(2):111–127. doi: 10.1080/13557850601081720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaholokula JK, Saito E, Mau MK, Latimer R, Seto TB. Pacific Islanders' perspectives on heart failure management. Patient Edu Couns. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.10.015. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mau MK, Glanz K, Severino R, Grove JS, Johnson B, Curb JD. Mediators of lifestyle behavior change in Native Hawaiians: Initial findings from the Native Hawaiian Diabetes Intervention Program. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(10):1770–1775. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.10.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group The Diabetes Prevention Program- Baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1619–1629. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.11.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung MW, Yen IH, Minkler M. Community based participatory research: A promising approach for increasing epidemiology's relevance in the 21st century. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(3):499–506. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]