Abstract

Lectins are carbohydrate binding proteins found in plants, animals and microorganisms. They serve as important models for understanding protein-carbohydrate interactions at the molecular level. We report here the fabrication of a novel sensing interface of biotinylated sialosides to probe lectin-carbohydrate interactions using surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy. The attachment of carbohydrates to the surface using biotin-NeutrAvidin interactions and the implementation of an inert hydrophilic hexaethylene glycol spacer between the biotin and the carbohydrate result in a well defined interface, enabling desired orientational flexibility and enhanced access of binding partners. The specificity and sensitivity of lectin binding were characterized using Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA) and other lectins including Maackia amurensis lectin (MAL), Concanavalin A (Con A), and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA). The results indicate that α2,6-linked sialosides exhibit high binding affinity to SNA, while alteration in sialyl linkage and terminal sialic acid structure compromises the affinity by a varied degree. Quantitative analysis yields an association constant (Ka) of 1.29 × 106 M−1 for SNA binding to Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB and a dissociation constant (KD) of 777 ± 93 nM. A linear relationship was obtained in the 10–100 μg/mL range with LOD of ~50 nM. Weak interactions with MAL, Con A and WGA were also quantified. The control experiment with bovine serum albumin indicates that nonspecific interaction on this surface is insignificant over the concentration range studied. Multiple experiments can be performed on the same substrate using a glycine stripping buffer, which selectively regenerates the surface without damaging the sialoside or the biotin-NeutrAvidin interface. This surface design retains a high degree of native affinity for the carbohydrate motifs, allowing distinction of sialyl linkages and investigation pertaining to the effect of functional group on binding efficiency. It could be easily modified to identify and quantify binding patterns of any low-affinity biologically relevant systems, opening new avenues for probing carbohydrate-protein interactions in real-time.

INTRODUCTION

Lectins are carbohydrate binding proteins of considerable specificity derived from plants, animals and microorganisms.1–3 Specifically, carbohydrate-protein interactions play key roles in modulating intracellular traffic,4 phagocytosis,5 endocytosis,6 cell-cell recognition,7 signal transduction,6 inflammation processes,8 and cancer cell metastasis.9 Structurally, lectins have shallow binding pockets, which results in relatively weak, non-covalent binding with affinity constants in the millimolar range.10–12 In addition, lectins are structurally complex and binding motifs are often not well understood.12 To overcome the weak-binding problem of the carbohydrate-lectin interaction, the use of multivalent interactions to enhance the binding affinity is often employed. This can be accomplished by varying the density of the lectin-carbohydrate recognition domains,9 clustering carbohydrates on the cell surface,13 or altering molecular topography by adjusting the length of linkers to improve their accessibility to ligands on opposing binding partners.14, 15

Many analytical and bioanalytical techniques have been employed to study protein-carbohydrate interactions, including NMR in conjunction with isothermal calorimetry and fluorescence spectroscopy,16 dual polarization interferometry,17 enzyme-linked lectin assays (ELLAs),18 impedance spectroscopy,19 quartz crystal microbalance (QCM),20–22 and microarray techniques.23, 24 A number of these methods require either labeling steps with convoluted chemistry or expensive materials and optics. To circumvent these drawbacks, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) has emerged as the method of choice in recent years to study carbohydrate-lectin interactions.13, 16, 25–30 SPR is advantageous for its intrinsic sensitivity that has been documented to be at least an order of magnitude higher than that of QCM for a comparable biological system.31 Also, the SPR method is fast and suitable for real time measurement. SPR has been used to study protein-carbohydrate interactions for the determination of affinity constants,32 equilibrium dissociation constants,30 and lectin specificity.33 However, SPR kinetic/thermodynamic studies have been limited to the use of proprietary prefabricated sensor surfaces thus far.

Meanwhile, the use of multifunctional surface chemistry characterized by SPR for carbohydrate-protein interactions is still an emerging scientific field. In order to effectively study carbohydrate-lectin interactions with SPR, optimal surface chemistry is of most significance. Previous work has used surface immobilized lectin due to easy fabrication.34–38 However, binding of a low molecular weight carbohydrate ligand (< 1000 Da) is difficult to quantify by SPR.11, 15 In contrast, immobilization of carbohydrate to the surface has the advantage of straightforward detection of large lectin molecules with the SPR method. In order to immobilize the carbohydrate efficiently, simple and well-understood surface chemistry must be developed. To date, several techniques have been attempted to immobilize carbohydrates, including copolymerization,39 reductive amination,40 chemical immobilization of carbohydrates through diazirine derivatization,41 self-assembled monolayers,42 and other covalent immobilizations.43 While these approaches have been successful for their specific systems, the complexity of most oligosaccharides can cause surface deformation and inhomogeneity.44 Therefore, alternative surface modification have been attempted.29, 45, 46 However, many of these strategies are multistep laborious protocols that often lead to inconsistent results. Surface immobilization of carbohydrates has been further complicated by the need to conserve the original structure and expose the functional sites so that the immobilized moiety can mimic the specific biomolecular interactions occurring on the cell surface. Because carbohydrates are flexible molecules, it has proven technically challenging to immobilize carbohydrates in an oriented fashion while retaining their inherent structures and functionalities.47

An important family of monosaccharide-containing structures that can be recognized by certain lectins are sialic acid (SA)-containing structures. SAs are α-keto acids that widely exist as components of the sugar chains of glycoconjugates in cells and tissues, playing important roles in many biological recognition mechanisms.48 Specifically, sialic acid is the binding moiety for numerous plant lectins including wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA), and Macckia amurensis lectin (MAL).49 In recent years, derivatives of sialic acid have shown various biological activities, aiding the development and production of medicines.50 However, many SA derivatives have yet to be tested on biological systems. In particular, sialyl trisaccharides containing various naturally existing sialic acid residues have yet to be studied extensively. These structures have varying levels of binding affinity to a number of lectins (SNA, MAL, WGA), making them conducive for structure-function relationship studies of carbohydrate-lectin interactions. In addition, sialyl trisaccharides can contain different sialic acid structures, sialyl-linkages, and underlying disaccharide structures, providing enough sophistication for understanding complex oligosaccharide-based biomolecular interactions systems. Furthermore, these sugars are generally amenable to efficient synthesis and modification by the one-pot multiple-enzyme chemoenzymatic synthetic system established in the Chen group.51–53

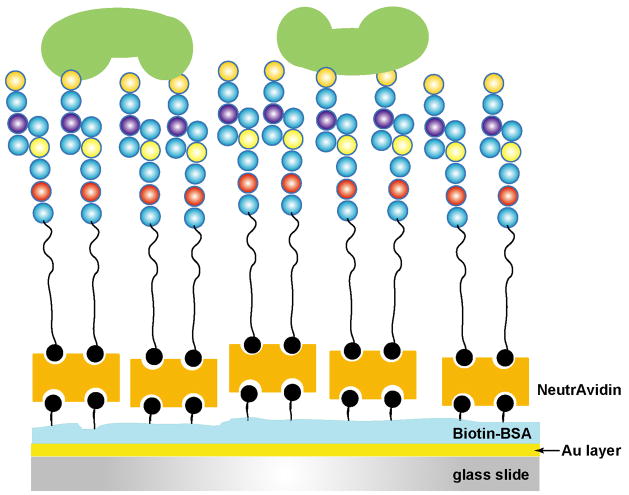

To create a reproducible and efficient biological mimic of carbohydrate-lectin interaction, we report the use of chemoenzymatically synthesized biotinylated sialyldisaccharides to study carbohydrate-lectin interactions. Figure 1 shows the schematic illustration of the sensing interface. While a number of surface chemistries have been employed to study carbohydrate-lectin interactions as mentioned previously, the use of biotin-avidin chemistry allows for strong binding (Ka = 1015 M−1), facilitating the removal of bound lectin, and eliminating the need for long incubation steps. The biotinylated sialosides contain a flexible hexaethylene glycol (HEG) spacer.54 The HEG linker allows orientational flexibility to closely mimic the sialoside-lectin interaction in its native conformation. The binding of Sambucus nigra agglutinin to sialosides was investigated and the kinetic data are reported and compared. This surface design is desirable for studies of both strong and weak biological interactions, enabling rapid determination of lectin-carbohydrate binding specificity in a highly sensitive manner.

Figure 1.

Cartoon representation of the carbohydrate-immobilized surface for lectin sensing.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and Instrumentation

Biotinylated bovine serum albumin (b-BSA) and NeutrAvidin were purchased from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL). Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA) was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Bovine serum albumin (BSA), wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), and Concanavalin A (Con A) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). An SPR spectrometer Biosuplar-2 (Analytical μ-Systems, Germany) with a light-emitting diode light source (λ=670 nm), high-refractive index prism (n = 1.61), and 30-mL flow cell was used for all SPR measurements. SPR gold chips were fabricated with a 46-nm-thick gold layer deposited by an e-beam evaporator onto cleaned BK-7 glass slides. All SPR experiments used 20 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4 with 150 mM NaCl) as a running buffer.

Synthesis of Biotinylated Sialosides

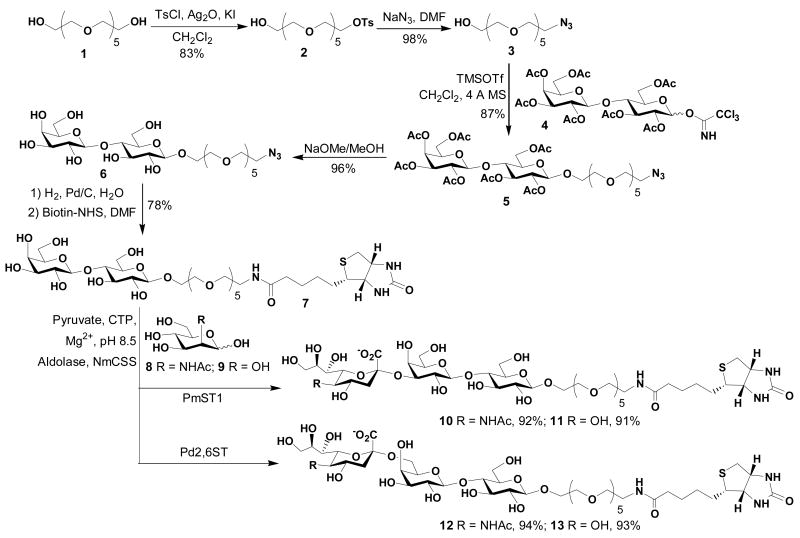

Monotosylation of hexa(ethylene glycol) (HEG, 1) was achieved in the presence of silver (I) oxide55 and potassium iodide with good yield. The HEG azide 3 was then prepared in 98% yield from the mesylate 2 by using sodium azide in N,N-dimethylformamide at 60 °C. Coupling of lactose trichloroacetimidate 4 with acceptor HEG azide 3 in the presence of TMSOTf afforded compound 5 in 87% yield. After deacetylation of 5 using NaOMe in methanol followed by hydrogenation of azido group to the primary amino group, the reduced product coupling with N-hydroxy succinamide ester of biotin (Biotin-NHS) in DMF afforded biotintylated lactoside (LHEB, 7) in 78% yield (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Chemoenzymatic synthesis of biotinylated sialosides 10–13.

Chemoenzymatic sialylation of 7 was achieved using a highly efficient and convenient one-pot three-enzyme system established in the Chen laboratory.51–53 In this system, N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc, 8) or mannose (9) was converted to Neu5Ac or KDN by an aldol condensation reaction catalyzed by an E. coli K-12 sialic acid aldolase, and then activated to form CMP-sialic acids catalyzed by an N. meningitidis CMP-sialic acid synthetase (NmCSS). The sialic acid residue in CMP-sialic acid was then transferred to the galactose moiety of the acceptor 7 by a multifunctional Pasteurella multocida sialyltransferase (PmST1) to form an α2,3-linked sialoside 10 (Neu5Acα2,3-LHEB) or 11 (KDNα2,3-LHEB), or by a Photobacterium damsela α2,6-sialyltransferase (Pd2,6ST) to form an α2,6-linked sialoside 12 (Neu5Acα2,6-LHEB) or 13 (KDNα2,3-LHEB), in high yields varying from 91–94% (Scheme 1). Sialoside products were purified by Bio-Gel P-2 gel filtration chromatography and the structures were characterized by 1H and 13C NMR as well as mass spectrometry (see Supporting Information).

SPR Analysis of Sambucus nigra Agglutinin on Biotinylated Sialosides Immobilized on the Gold Substrates

Surface interaction and modification was monitored and characterized using the tracking mode of SPR angular scanning around the minimum angle. To prepare the sensing surface, a previous protocol was modified.56 Briefly, gold substrates were rinsed with ethanol and ultra pure water. After drying under a gentle stream of N2 gas, the gold substrates were clamped down by a flow cell on a high-refractive index prism for use. Once PBS buffer had established a smooth baseline across the surface, biotin-BSA (0.5 mg/mL in PBS) was injected across the gold chip. The modified surface was allowed to incubate for 30 min and then rinsed with PBS for 15 min to wash away any non-specifically adsorbed species. NeutrAvidin (0.5 mg/mL in PBS), a tetramer that forms a very stable complex with biotin, was subsequently injected across the sensing surface and incubated for 90 min to allow binding to biotin-BSA, while leaving additional biotin binding sites. Once a stable signal was observed, the surface was rinsed with PBS for 30 min. The constructed sensor chip was then injected with a biotinylated sialoside such as Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB (1.0 mg/mL in PBS) and allowed to incubate for 30 min and rinsed with PBS for 30 min.

SNA solutions diluted in PBS with concentrations varying from 10 to 1000 mg/mL were injected onto the carbohydrate-functionalized surface. Each aliquot was incubated for 60 min and then rinsed with PBS for 30 min. Upon rinsing the lectin-immobilized surface, the minimum angle decreased slightly over time, characteristic of lectin dissociation kinetics.26 The free biotinylated-carbohydrate functionalized surface was regenerated with 100 mM glycine (pH 1.7) stripping buffer to remove bound lectin. Once the carbohydrate baseline had been established, a second aliquot of the same concentration of lectin was injected and the entire process was repeated. Each calibration standard was obtained in triplicate on the same substrate.

For the experiments with surfaces immobilized with different carbohydrates, the same surface modification procedure was followed as above except that a different biotinylated carbohydrate was used in place of Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB. Similarly, for experiments with various lectins, the same surface modification procedure was followed as above except that a different lectin was used in place of SNA. For each different set of binding process, carbohydrates and lectins diluted in PBS with a final concentration of 1.0 mg/mL were used as standards.

Data Analysis and Determination of Kinetic Constants

The dissociation constant (KD) value for the interaction between Sambucus nigra lectin (SNA) and Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB was measured from saturation binding experiments. Increasing concentrations of SNA (10 mg/ml to 1 mg/ml) were injected over the Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB functionalized surface and the minimum angle shift was recorded. The value for KD was obtained using a non-linear least squares analysis outlined previously57 with eq 1

| (1) |

where ABeq is the average of the response signal at equilibrium in defined intervals for each concentration of SNA [A] and ABmax is the maximum response that can be obtained for lectin binding depending on the number of binding sites available on the Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB functionalized surface.58 Ka can then be determined by the reciprocal value of the KD. All other data analysis was performed using Origin software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Surface Chemistry, Detection, and Regeneration

The surface chemistry employed in this work reflects our desire of using SPR to study the relatively weak affinity in carbohydrate-lectin interactions with high accuracy. The choice of Sambucus nigra agglutinin as the target was aimed to understand the general binding characteristics of lectins to carbohydrates with a wide affinity distribution in the micromolar-millimolar range. The scheme in Figure 1 offers simplicity in surface chemistry to provide a unique interface for detecting the generally weak interactions. The structures for the synthesized biotinylated SA are depicted in Scheme 1 (labeled 10–13). We have focused initially on Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB due to the high SNA affinity for a2,6 linked sialosides.59, 60 The hydrophilic hexaethylene glycol (HEG) spacer allows flexible movement of the carbohydrate immobilized to the surface via biotin-NeutrAvidin binding, thus enhancing the affinity of interaction of the carbohydrates and carbohydrate-binding lectins. Biotinylated sialosides that varied either in the sialyl linkage or the substituent at C-5 of the Neu5Ac were used for comparison. Biotin occupies the opposite end of the PEG spacer, providing highly specific binding to an avidin protein sublayer. The strong interaction of biotin-avidin61–63 was used in hope to remove the bound lectin for repeat use without damaging the sialoside-immobilized surface. After testing a class of avidin proteins, we found that NeutrAvidin has the lowest nonspecific binding in the avidin family most likely due to its deglycosylated structure. Together with the better performance in biotin-binding, it is selected for use in all the experiments reported here.

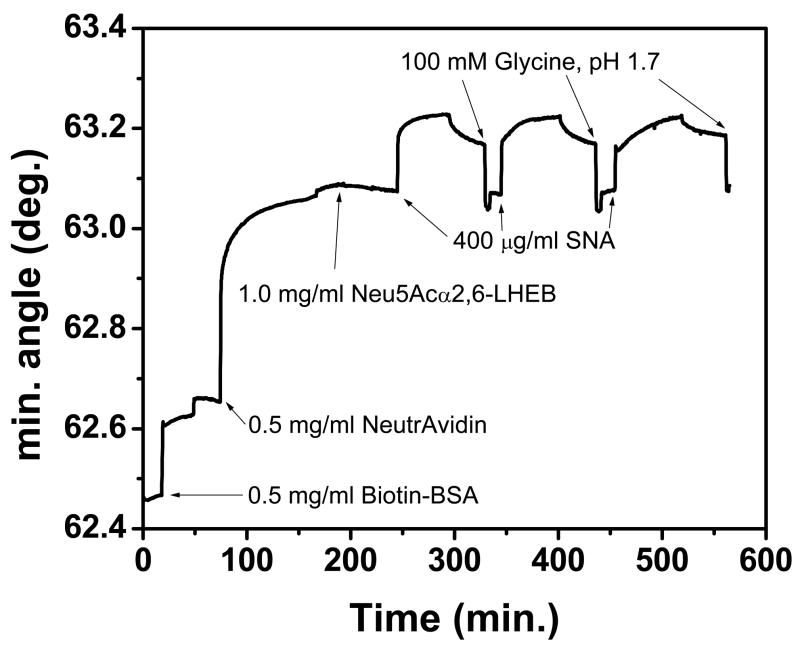

The SPR sensorgram for the interaction of Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB with SNA is shown in Figure 2. Upon addition of 400 mg/mL SNA to the Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB functionalized surface, slow binding was observed, which is common for carbohydrate-lectin interactions. When the surface was rinsed with buffer, the lectin dissociated rapidly due to weak carbohydrate-lectin interaction, similar to previous SPR studies.15, 26, 34, 64 It is highly desirable if such a surface can be regenerated with a simple reagent that largely preserves the native binding structures. Although various stripping buffers have been used for SPR studies, we found that very few of them performed well on a carbohydrate surface. After testing multiple stripping buffers, the best results were obtained with 100 mM glycine, pH 1.7. This stripping buffer was modified from a previous protocol in which the buffer was used to strip antibodies from a binding surface.65 The capability of reusing the sialoside-immobilized surface was tested by repeated injection of aliquots of 400 mg/ml SNA, followed by addition of the glycine buffer. This greatly reduces material consumption required by the SPR apparatus, and significantly decreases assembly and experimental time. In addition, the new stripping buffer allows facile quantitation and direct comparison on the shape of kinetic curves by providing the same baseline of the carbohydrate-coated surface. In comparison, other surface chemistries that have been attempted, including self-assembled monolayers (SAMs), are time consuming (requiring overnight incubation), require chemical modification, and are less sensitive to lectin binding than the aforementioned surface.

Figure 2.

Characteristic sensorgram for carbohydrate functionalized sensing surface in response to 400 mg/ml SNA.

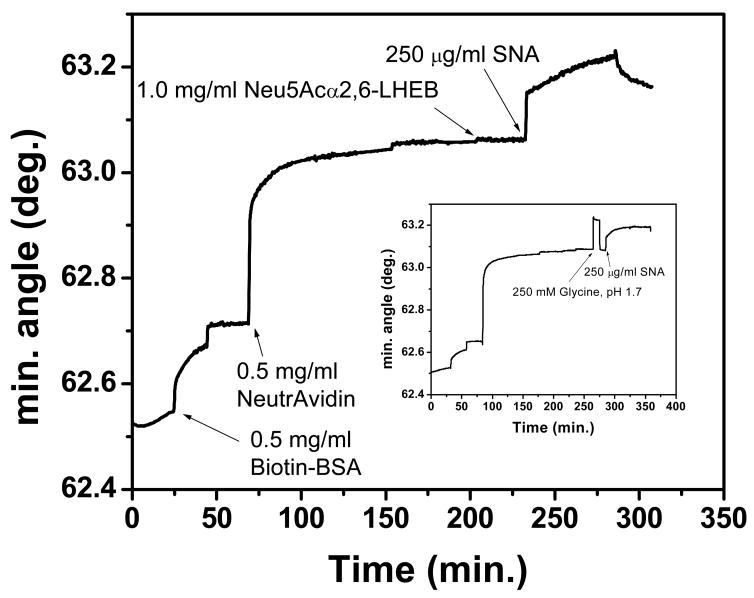

To ensure that the surface regeneration did not damage the carbohydrate-functionalized surface, 250 mM glycine, pH 1.7 was injected over the Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB derivatized surface before the addition of 250 mg/ml SNA (Figure 3, insert). The data obtained was then compared to a surface in which 250 mg/ml SNA was injected without prior addition of glycine (Figure 3). A comparison of the two experiments shows a similar equilibrium binding level of lectin, with corresponding angular changes of 0.145º and 0.149º, the latter representing the glycine-free assay. This demonstrates the unique ability of this low pH buffer to provide a fresh sensor surface after each injection of lectin without compromising surface functionality. A higher concentration of glycine (250 mM) was used in this case to prove that under even harsher conditions, the lectin binding response would not be diminished by the stripping buffer. For all other experiments, the concentration of glycine was optimized at 100 mM, providing complete lectin removal to the carbohydrate baseline and establishing a fully functional surface capable of subsequent binding analyses, as depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Sensorgram of Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB functionalized surface upon addition of 250 mg/ml SNA. Inset: Identical sensorgram except that a 250 mM glycine stripping buffer of pH 1.7 is added before the addition of SNA.

Lectin Quantitation and Kinetic Analysis

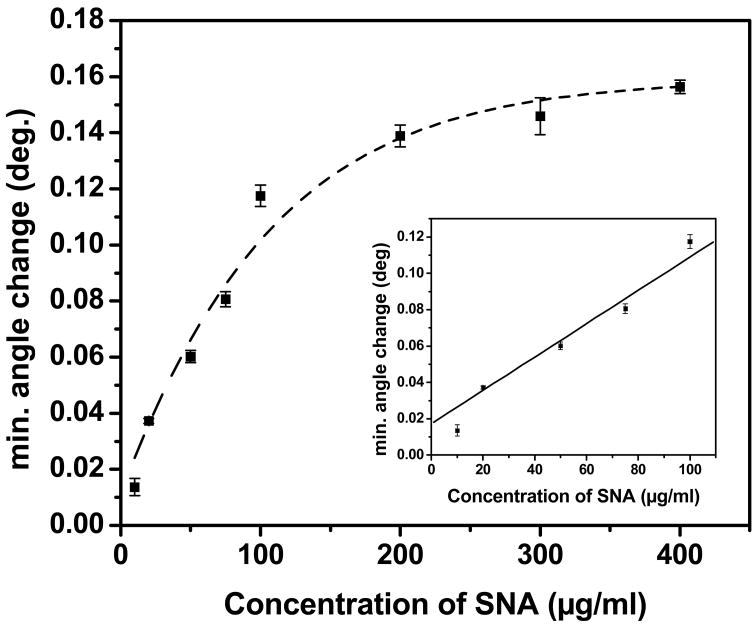

The Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB functionalized surface was further tested over a wide range of physiologically relevant concentrations of SNA to evaluate its analytical performance (Figure 4).21, 27 At higher concentrations of SNA, more binding sites become occupied, resulting in saturation binding kinetics as expected. Using the linear portion of the response curve to increasing concentrations of SNA (Figure 4, insert), the limit of detection (LOD) was determined to be 8.01 mg/ml or 53.3 nM. Our results are comparable to most recent work using a similar approach.27 It should be noted that the literature reported system used a higher concentration of immobilized carbohydrate and more expensive instrumentation, and each assay took more than a day to complete.27 Our work yielded a dynamic range over several orders of magnitude (10–400 mg/ml SNA or high nM range), which is considerably better than the range observed for a similar QCM system21 and on par with another SPR studies.27 In comparison to recent carbohydrate-lectin studies, our design offers distinctive advantages in that the experiments were performed with inexpensive instrumentation, simple and well-understood chemistry, allowing regeneration of the sensing surface to yield reproducible results.

Figure 4.

Sensing response obtained by addition of increasing concentrations of Sambucus nigra lectin to a Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB immobilized surface. Inset: Linear portion of response curve before saturation binding occurs.

SPR sensorgrams provided values for the determination of the dissociation constant (KD) and association constant (Ka). The values for both Ka (1.29 x 106 M−1) and KD (777 ± 93 nM) were quite consistent with previously reported constants for similar systems.13, 26, 29 Specifically, two separate reports studied the interaction of SNA with sialic acid terminated a2,6 conjugates by immobilizing SNA. Haseley et al. employed a similar oligosaccharide and determined an affinity constant that was very similar to ours (1.9 x 106 M−1),66 while Duverger et. al. showed a slightly higher binding affinity (4.5 x 106 M−1),67 likely due to the use of a neoglycoprotein which is known to enhance affinity constants.15

Screening of Carbohydrate–Lectin Interactions

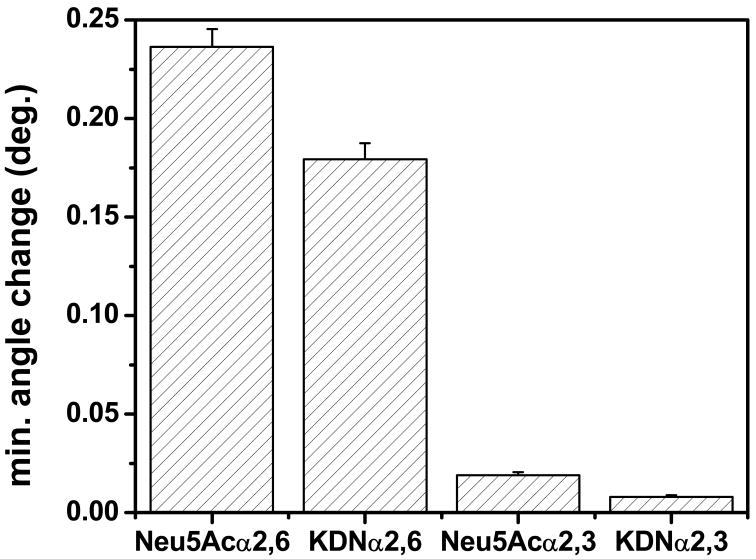

The surface system was further tested using three additional structurally similar sialosides (10, 11, and 13 in Scheme 1) at the saturation concentration of SNA (Figure 5). Results demonstrate structure-dependent variation on binding characteristics, with the Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB immobilized surface having the highest affinity to SNA. Thereafter, the KDNa2,6-LHEB immobilized surface also showed significant binding. By using two biotinylated sialosides containing a Neu5Ac or a KDN, our surface design was able to clearly distinguish these compounds altering only one functional group on the sialic acid (Neu5Ac has an N-acetyl group at C5, while KDN has a hydroxyl group at C5). SNA showed a significant decrease in binding to Neu5Aca2,3-LHEB surface compared to Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB, demonstrating the importance of sialyl linkages in the SNA binding. This result is consistent with several previous reports 60, 66, 67 and emphasizes the importance of sialyl linkage in lectin binding specificity. KDNa2,3-LHEB displayed slightly weaker binding than Neu5Aca2,3-LHEB for reasons indicated above with regards to replacing the C5 N-acetyl group in Neu5Ac to C5 hydroxyl group in KDN. This information would be useful for future work to design other carbohydrate functionalized surfaces to study weak biomolecular interactions.

Figure 5.

Relative affinity of SNA at saturation concentration on surfaces immobilized with different biotinylated sialosides.

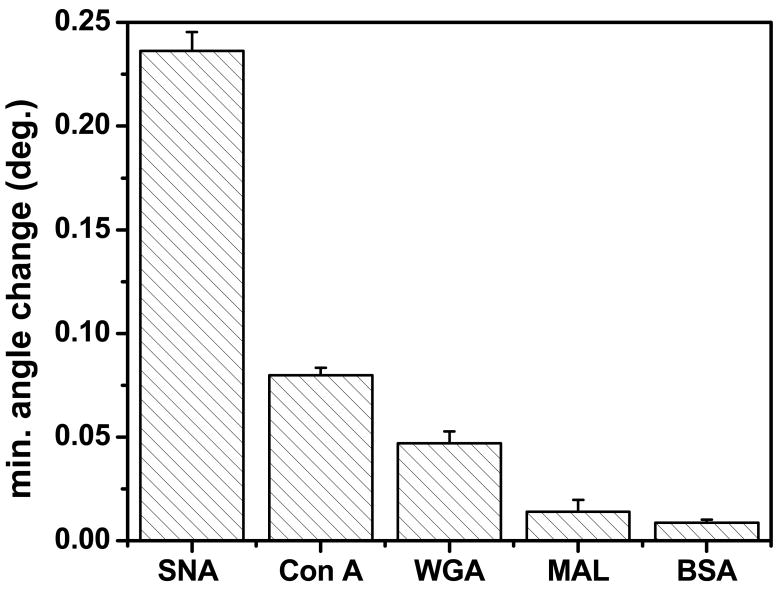

The Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB functionalized surface was also used to test four additional proteins or lectins at saturation concentrations (Figure 6). The strongest binding protein was SNA, followed by Con A, which is known to specifically bind to mannosylated surfaces.68 Mannose is a stereoisomer of both galactose and glucose, which are the monosaccharides comprising the lactose that is present on all of the four biotinylated sialosides used here. In fact, Con A exhibits a primary specificity for mannose, but will also bind glucose.69,70 Therefore, a relatively strong binding signal to Con A is expected, yet weaker than that of SNA. Additionally, the binding to wheat germ agglutinin was slightly weaker than that of Con A. While WGA does have affinity for sialic acid,71 it is a secondary interaction with affinity fourfold less than its affinity to N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) according to a hapten-inhibition study of the methyl ester of sialic acid.69 Thus the lack of strong binding exhibited by WGA to the Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB immobilized surface was expected. The binding of Maackia amurensis lectin (a lectin known to bind to Neu5Aca2,3Lac(NAc) trisaccharide containing structures)48, 60 to the Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB immobilized surface was even weaker. Finally, the weakest binding protein was bovine serum albumin. BSA has no known affinity towards any specific carbohydrate, so binding should be minimal. The result also confirms that the nonspecific interaction on this surface is insignificant over this concentration range. Overall, we believe that these results show the applicability of this surface to be used to distinguish many different types of lectins and carbohydrates in a quantitative and real-time manner.

Figure 6.

Binding intensity of different lectins to a Neu5Aca2,6-LHEB functionalized surface.

CONCLUSIONS

With the use of simple and highly effective surface chemistry based on biotinylated sialosides, we have shown the study of carbohydrate-lectin interactions in a detailed, quantitative fashion. Structure-dependent variation of sialoside-lectin binding was observed for different lectins and different carbohydrate-immobilized surfaces. These results indicate the sensing surface described here could be broadly applied to a wide variety of biologically relevant low-affinity systems beyond the carbohydrate-lectin interaction studies shown here. The bare carbohydrate surface could be reproduced multiple times without degradation of the binding signal. In addition, this surface design has high sensitivity for weak carbohydrate-lectin interactions due to unique surface chemistry employed. Its ability to distinguish subtle changes on the ligand of carbohydrate-binding protein is remarkable. One could envision transforming the current system to microarray format for high-throughput screening of weak biological interactions. Future work will focus on optimizing the immobilization density of the oligosaccharides and determining the ideal biotin-linker for the sialosides for maximum sensitivity in monitoring carbohydrate-lectin interactions.

Supplementary Material

Experimental details for synthesis, NMR, and MS data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

QC would like to acknowledge the support from NSF grant CHE-0719224. XC acknowledges the support from NIH R01 GM076360.

References

- 1.Sharon N, Lis H. Lectins. 2. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soderstrom K. Cancer. 1987;60:1823–1831. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19871015)60:8<1823::aid-cncr2820600825>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naeem A, Saleemuddin M, Khan RH. Curr Protein Pept Sc. 2007;8:261–271. doi: 10.2174/138920307780831811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lis H, Sharon N. Chem Rev. 1998;98:637–674. doi: 10.1021/cr940413g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varki A. Glycobiology. 1993;3:97–130. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sacchettini JC, Baum LG, Brewer CF. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3009–3015. doi: 10.1021/bi002544j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakomori S. Glycoconj J. 2004;21:125–137. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000044844.95878.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertozzi CR, Kiessling LL. Science. 2001;291:2357–2364. doi: 10.1126/science.1059820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monsigny M, Mayer R, Roche AC. Carbohydrate Letters. 2000;4:35–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith EA, Thomas WD, Kiessling LL, Corn RM. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6140–6148. doi: 10.1021/ja034165u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann D, Kanai M, Maly DJ, Kiessling LL. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:10575–10582. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rini JM. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1995;24:551–577. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.24.060195.003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Luo S, Tang Y, Yu L, Hou KY, Cheng JP, Zeng X, Wang PG. Anal Chem. 2006;78:2001–2008. doi: 10.1021/ac051919+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crocker PR, Feizi T. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:679–691. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shinohara Y, Hasegawa Y, Kaku H, Shibuya N. Glycobiology. 1997;7:1201–1208. doi: 10.1093/glycob/7.8.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murthy BN, Voelcker NH, Jayaraman N. Glycobiology. 2006;16:822–832. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricard-Blum S, Peel LL, Ruggiero F, Freeman NJ. Anal Biochem. 2006;352:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu JH, Singh T, Herp A, Wu AM. Biochimie. 2006;88:201–217. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.La Belle JT, Gerlach JQ, Svarovsky S, Joshi L. Anal Chem. 2007;79:6959–6964. doi: 10.1021/ac070651e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen Z, Huang M, Xiao C, Zhang Y, Zeng X, Wang PG. Anal Chem. 2007;79:2312–2319. doi: 10.1021/ac061986j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pei Y, Yu H, Pei Z, Theurer M, Ammer C, Andre S, Gabius HJ, Ramstrom O. Anal Chem. 2007;79:6897–6902. doi: 10.1021/ac070740r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebed K, Kulik AJ, Forro L, Lekka M. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2006;299:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2006.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang PH, Wang SH, Wong CH. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11177–11184. doi: 10.1021/ja072931h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuno A, Uchiyama N, Koseki-Kuno S, Ebe Y, Takashima S, Yamada M, Hirabayashi J. Nat Methods. 2005;2:851–856. doi: 10.1038/nmeth803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yonzon CR, Jeoung E, Zou S, Schatz GC, Mrksich M, Van Duyne RP. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12669–12676. doi: 10.1021/ja047118q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duverger E, Frison N, Roche AC, Monsigny M. Biochimie. 2003;85:167–179. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(03)00060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vornholt W, Hartmann M, Keusgen M. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22:2983–2988. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terada T, Nishikawa M, Yamashita F, Hashida M. Int J Pharm. 2006;316:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suda Y, Arano A, Fukui Y, Koshida S, Wakao M, Nishimura T, Kusumoto S, Sobel M. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006;17:1125–1135. doi: 10.1021/bc0600620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krotkiewska B, Pasek M, Krotkiewski H. Acta Biochim Polon. 2002;49:481–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su X, Wu YJ, Knoll W. Biosens Bioelectron. 2005;21:719–726. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapoor M, Thomas CJ, Bachhawat-Sikder K, Sharma S, Surolia A. Method Enzymol. 2003;362:312–329. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)01022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto K, Ishida C, Shinohara Y, Hasegawa Y, Konami Y, Osawa T, Irimura T. Biochemistry. 1994;33:8159–8166. doi: 10.1021/bi00192a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi Y, Nakamura H, Sekiguchi T, Takanami R, Murata T, Usui T, Kawagishi H. Anal Biochem. 2005;336:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frison N, Marceau P, Roche AC, Monsigny M, Mayer R. Biochem J. 2002;368:111–119. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mislovicova D, Masarova J, Svitel J, Mendichi R, Soltes L. Bioconjug Chem. 2002;13:136–142. doi: 10.1021/bc015517u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bachhawat K, Thomas CJ, Amutha B, Krishnasastry MV. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5541–5546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takagaki KH, Kakizaki I, Iwafune M, Itabashi T, Endo M. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8882–8889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hatanaka K, Takeshige H, Akaike T. J Carbohyd Chem. 1994;13:603–610. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biskup MB, Muller JU, Weingart R, Schmidt RR. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:1007–10015. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chevolot Y, Martins J, Milosevic N, Leonard D, Zeng S, Malissard M, Berger EG, Maier P, Mathieu HJ, Crout DH, Sigrist H. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:2943. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhi Z, Powell AK, Turnbull JE. Anal Chem. 2006;78:4786–4793. doi: 10.1021/ac060084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jelinek R, Kolusheva S. Chem Rev. 2004;104:5987–6015. doi: 10.1021/cr0300284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seo JH, Adachi K, Lee BK, Kang DG, Kim YK, Kim KR, Lee HY, Kawai T, Cha HJ. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:2197–2201. doi: 10.1021/bc700288z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Paz JL, Noti C, Seeberger PH. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2766–2767. doi: 10.1021/ja057584v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang DN, Liu SY, Trummer BJ, Deng C, Wang AL. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:275–281. doi: 10.1038/nbt0302-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukui S, Feizi T, Galustian C, Lawson AM, Chai W. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:1011–1017. doi: 10.1038/nbt735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamamoto K, Konami Y, Irimura T. J Biochem. 1997;121:756–761. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Damme E, Pusztai A, Bardocz S. Handbook of Plant Lectins: Properties and Biomedical Applications. John Wiley and Sons; NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Furuhata K. Trends Glycosci Glyc. 2004;16:143–169. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu H, Chokhawala H, Karpel R, Wu B, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Jia Q, Chen X. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17618. doi: 10.1021/ja0561690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu H, Huang S, Chokhawala H, Sun M, Zheng H, Chen X. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:3938. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu H, Chokhawala, Huang S, Chen X. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2485. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kheirolomoom A, Dayton PA, Lum AF, Little E, Paoli EE, Zheng H, Ferrara KW. J Control Release. 2007;118:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bouzide A, Sauve G. Org Lett. 2002;4:2329–2332. doi: 10.1021/ol020071y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whelan RJ, Zare RN. Anal Chem. 2003;75:1542–1547. doi: 10.1021/ac0263521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harris DC. J Chem Educ. 1998;75:119–121. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Navratilova I, Myszka DG. Surface Plasmon Resonance Based Sensors. Vol. 4. Springer-Verlag; 2006. pp. 159–161. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shibuya N, Goldstein IJ, Broekaert WF, Nsimba-Lubaki M, Peeters B, Peumans WJ. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:1596–1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Knibbs RN, Goldstein IJ, Ratcliffe RM, Shibuya N. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grun CH, Van Vliet SJ, Schiphorst W, Bank C, Meyer S, Van Die I, Van Kooyk Y. Anal Biochem. 2006;354:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Green NM. Biochem J. 1963;89:585–591. doi: 10.1042/bj0890585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Green NM. Adv Protein Chem. 1975;29:85–133. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vila-Perello M, Gallego RG, Andreu D. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:1831–1838. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Phillips KS, Han JH, Cheng Q. Anal Chem. 2007;79:899–907. doi: 10.1021/ac0612426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haseley SR, Talaga P, Kamerling JP, Vliegenthart JF. Anal Biochem. 1999;274:203–210. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duverger E, Coppin A, Strecker G, Monsigny M. Glycoconjugate J. 1999;16:793–800. doi: 10.1023/a:1007131931851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mangold SL, Cloninger MJ. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:2458–2465. doi: 10.1039/b600066e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liener IE, Sharon N, Goldstein IJ, editors. The Lectins: Properties, Functions, and Applications in Biology and Medicine. 40–41. Academic Press Inc; Orlando: 1986. pp. 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hong M, Cassely A, Mechref Y, Novtny M. J Chromatogr-Biomed. 2001;752:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)00564-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peters BP, Ebisu S, Goldstein IJ, Flashner M. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5505–5511. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental details for synthesis, NMR, and MS data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.