The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recently reported nationwide epidemics of Fusarium and Acanthamoeba keratitis.1 2 These investigations were prompted by reports of increased cases at individual sites.3-5 It can be difficult to detect outbreaks at a single centre due to changing diagnostic criteria, changing referral patterns, and the effects of chance. The objective of the current study was to determine if the recent outbreaks of Fusarium or Acanthamoeba keratitis could be identified from data obtained from a single centre, the F I Proctor Foundation at the University of California, San Francisco. Using the Maximum Excess Events Test (MEET), which detects clustering within years and between years, we confirmed epidemics consistent with the recently reported epidemics of Fusarium and Acanthamoeba keratitis. Our study shows that it is possible for a single centre to detect an outbreak.

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the culture results from clinically diagnosed non-herpetic corneal ulcers seen from 1987 through May 2007 at the F I Proctor Foundation. We did not culture for Acanthamoeba species prior to 1987, and diagnostic techniques have remained the same since then. For statistical detection of outbreaks, we used the MEET (with 10 000 Monte Carlo replications), which detects clustering within years and between years.6 To control for changing referral patterns, we used the total number of cultures as a denominator and replicated the analyses using the number of positive cultures for any organism as a denominator.

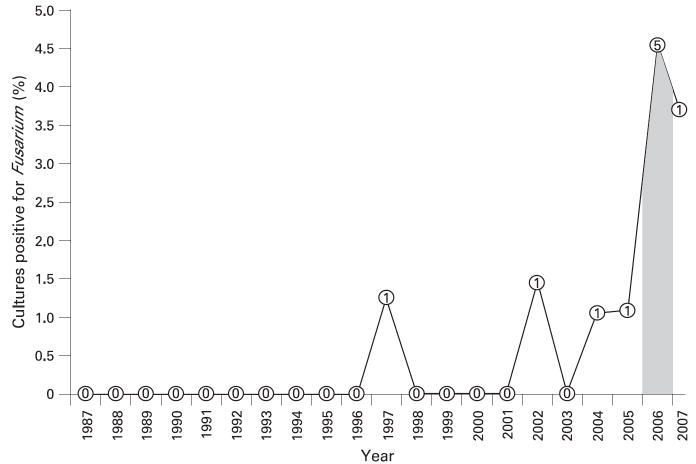

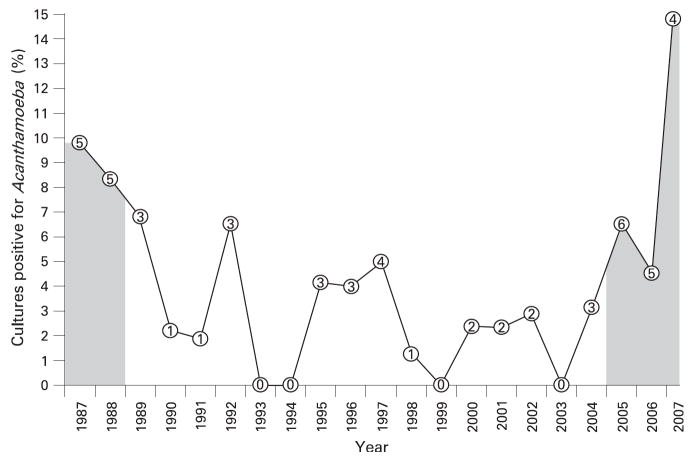

The average numbers of patients undergoing corneal cultures was 67 per year, ranging from 27 to 110. The total number of isolates identified as bacteria, fungi or Acanthamoeba was 26 per year, ranging from 15 to 44. Using total number of cultures as a denominator, we found evidence of temporal clustering of Fusarium cases (p = 0. 0007), with post-hoc analysis identifying an epidemic in 2006 (p = 0.001) (fig 1). We also found evidence of temporal clustering of Acanthamoeba case counts (p = 0.02). Two epidemics were identified, the first from 1987 to 1988 and the second from 2005 to May 2007 (p = 0.006) (fig 2). Similar results were obtained when the analyses were carried out using the number of positive cultures rather than the number of cultures taken.

Figure 1.

Incidence of Fusarium keratitis at the F I Proctor Foundation, 1987–2007. The curve shows the percentage of all cultures in each year that were positive for Fusarium species. The absolute number of cases for each year is indicated within the plotting circle. The shaded region indicates the time of the excess clustering (distribution of Tango’s focused clustering statistic, using re-sampling, conditional on rejection of the null hypothesis with MEET).6 Data were available through May 2007.

Figure 2.

Incidence of Acanthamoeba keratitis at the F I Proctor Foundation, 1987–2007. The curve shows the percentage of all cultures in each year that were positive for Acanthamoeba species. The absolute number of cases for each year is indicated within the plotting circle. The shaded regions indicate times of the excess clustering. Data were available through May 2007.

Comment

Consistent with the recent international epidemic of Fusarium keratitis,1 our analysis identified an epidemic of Fusarium keratitis at our institution in 2006. Likewise, we confirmed epidemics of Acanthamoeba keratitis at our institution in 1987–8 and 2005–7. These epidemics could not be explained by a change in our diagnostic techniques or a change in the number of cultures performed. The 1987–8 epidemic of Acanthamoeba keratitis has previously been attributed to homemade contact lens solutions. The reason for the recent increase in Acanthamoeba keratitis is unknown, but possibilities include contaminated tap water and the use of certain contact lens solutions.2 3 5

It is possible for a single centre to detect an outbreak, but institutions need to be wary of changing referral patterns and diagnostic criteria. The introduction of a technique such as confocal microscopy is exciting. However, if a new test is more sensitive (or less specific), centres can expect an increase in their reported incidence of an infection, whether or not there is an outbreak. Even with consistent diagnostic criteria, it can be difficult to assess whether an increase in cases is due to chance. Although an individual centre can detect an outbreak, the formation of a multi-centre network to monitor for early detection of new epidemics of infectious ocular diseases may be in order.

Acknowledgments

Funding: TML is supported by National Eye Institute grants U10-EY015114 and a Research to Prevent Blindness award, and NRA by a K23EY017897 and a Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award. The sponsors had no role in the design or conduct of the study, data analysis or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Approval for this study was obtained from the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco.

References

- 1.Chang DC, Grant GB, O’Donnell K, et al. Multistate outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with use of a contact lens solution. JAMA. 2006;296:953–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.8.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anon. Acanthamoeba keratitis multiple states, 2005–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:532–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joslin CE, Tu EY, McMahon TT, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of a Chicago-area Acanthamoeba keratitis outbreak. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:212–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khor WB, Aung T, Saw SM, et al. An outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with contact lens wear in Singapore. JAMA. 2006;295:2867–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.24.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thebpatiphat N, Hammersmith KM, Rocha FN, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis: a parasite on the rise. Cornea. 2007;26:701–6. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31805b7e63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tango T. A test for spatial disease clustering adjusted for multiple testing. Stat Med. 2000;19:191–204. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000130)19:2<191::aid-sim281>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]