Abstract

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) prolyl 4-hydroxylases are a family of iron- and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases that negatively regulate the stability of several proteins that have established roles in adaptation to hypoxic or oxidative stress. These proteins include the transcriptional activators HIF-1α and HIF-2α. The ability of the inhibitors of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases to stabilize proteins involved in adaptation in neurons and to prevent neuronal injury remains unclear. We reported that structurally diverse low molecular weight or peptide inhibitors of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases stabilize HIF-1α and up-regulate HIF-dependent target genes (e.g. enolase, p21waf1/cip1, vascular endothelial growth factor, or erythropoietin) in embryonic cortical neurons in vitro or in adult rat brains in vivo. We also showed that structurally diverse HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibitors prevent oxidative death in vitro and ischemic injury in vivo. Taken together these findings identified low molecular weight and peptide HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibitors as novel neurological therapeutics for stroke as well as other diseases associated with oxidative stress.

Iron maintains a unique role in physiology via its ability to change readily its oxidation state in response to changes in its local environment. A general simplification of its primary function is that it mediates one-electron redox reactions. This chemical property of iron enables it to act as an essential component in several biological activities, including as a cofactor for enzymes such as tyrosine hydroxylase. Oxygen binding to biomolecules such as hemoglobin and myoglobin is also coordinated by iron. Indeed iron deficiency can lead to a host of disorders, including anemia and restless legs syndrome (1).

Paradoxically, the biochemical properties that make iron beneficial in many biological processes appear to be a drawback when the balance between its accumulation/sequestration within cellular compartments and its release is disturbed in favor of iron accumulation (2). Indeed, iron overload is associated with several neurological conditions (3-5). For example, the iron content of nigral Lewy bodies is elevated in patients with Parkinson disease (6-9). Alzheimer disease has also been found to be associated with an increase in the iron content of senile plaques (10-15). Accumulation of mitochondrial iron has been shown to play a role in Friedrich ataxia (16, 17). Similarly, changes in intracellular free iron levels have been observed in cerebral ischemia (18-20). Direct evidence that disrupted iron homeostasis contributes to injury rather than simply being caused by it has been obtained by treatment with low molecular weight iron chelators or by overexpression of iron storage proteins. Small molecule iron chelators such as deferoxamine mesylate (DFO)2 inhibit neuronal injury in rodent models of stroke (21), Parkinson disease (22), and multiple sclerosis (23). Moreover, DFO and some other metal chelators such as clioquinol have been shown to slow the progression of Alzheimer disease in humans (24, 25). Similarly, the forced expression of the iron binding and storage protein ferritin in the substantia nigra diminishes iron accumulation and prevents neuronal loss in a rodent model of Parkinson disease (26). Together, these findings suggest that iron-dependent toxicity is part of the affector pathway of injury in a host of neurological conditions.

How do iron chelators prevent neuronal injury? Iron is generally believed to participate in neuronal dysfunction and death through its ability to catalyze (via electron donation) the generation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals via Fenton chemistry (1). In this model hydroxyl radicals modify lipid, protein, and DNA targets to induce cell dysfunction in these cellular constituents (27). It has been proposed that iron chelators can inhibit Fenton chemistry and prevent neuronal cell injury by sequestering accumulated free iron; however, this pathway of protection remains controversial. Indeed, prior studies from our laboratory have suggested alternative pathways of protection by iron chelators.

In an in vitro model of oxidative stress, we correlated the protective effects of iron chelators with their ability to activate the transcriptional activator hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (28). In this scheme, iron chelators inhibit the activity of a class of iron-dependent enzymes called the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases. Inhibition of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases prevents the attachment of an OH group (hydroxylation) to phylogenetically conserved proline residues at amino acid 402 and 564 in the protein HIF-1α (29). Unhydroxylated HIF-1α does not bind the ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase, von Hippel-Lindau protein (30-32). HIF-1α is thus not ubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome. Once stabilized, nuclear HIF-1α can heterodimerize with its partner HIF-1β, bind to the pentanucleotide hypoxia-response element (5′-TGATC-3′) in gene regulatory regions, and transactivate the expression of established protective genes, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and erythropoietin (33, 34). According to this model, the protective effects of iron chelators are not exclusively the result of suppression of Fenton chemistry, but may also result from the inhibition of iron-dependent prolyl hydroxylases. However, direct evidence that HIF-prolyl hydroxylase inhibition is a relevant target for protection from oxidative death by iron chelators has yet to be presented. In this paper we show that small molecule or peptide inhibitors of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases are sufficient to inhibit neuronal death because of oxidative stress in vitro and because of permanent focal ischemia in vivo. These results implicate HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases as targets for neuroprotection in the central nervous system.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Compound A, a proprietary compound, was obtained from Fibrogen Inc. DFO and 3,4-DHB were purchased from Sigma. Tat-HIF/ODD/wt (YGKKRRQRRRDLDLEMLAPYIPMDDDFQL) and Tat-HIF/ODD/mut (YGKKRRQRRRDLDLEMLAAYIAMDDDFQL) peptides were synthesized by Biopolymers Laboratory, Harvard Medical School. 40, 100, and 10 μm of compound A, DFO, and 3,4-DHB, respectively, were used throughout the studies unless otherwise stated. Peptides were used at a concentration of 100 μm unless otherwise stated.

Primary Neurons

Cell cultures were obtained from the cerebral cortex of fetal Sprague-Dawley rats (embryonic day 17) as described previously (35). All experiments were initiated 24 h after plating. Under these conditions, the cells are not susceptible to glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity.

Immunoblot Analysis

Cell lysates were obtained by rinsing cortical neurons with cold PBS and adding 0.1 m potassium phosphate containing 0.5% Triton X-100. Samples were then boiled in Laemmli buffer and electrophoresed under reducing conditions on 12% polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad). Nonspecific binding was inhibited by incubation in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST: 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.9% NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5% nonfat dried milk for 1.5 h. Primary antibodies against aldolase (rabbit muscle; Rockland), α-tubulin (Sigma), HIF-1α (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), VEGF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and p21 (BD Biosciences) were diluted 1:2000, 1:2000, 1:500, 1:400 and 1:500, respectively, in TBST containing 1% milk overnight at 4 °C followed by incubation with respective horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive proteins were detected according to the enhanced chemiluminescent protocol (Amersham Biosciences).

Luciferase Assay

Primary neurons infected with adenovirus (multiplicity of infection = 100) containing luciferase gene driven by an HRE promoter (a kind gift from Dr. Robert Freeman) were treated with DFO, 3,4-DHB, compound A, and the HIF-peptides overnight. The luciferase assay was performed using the bioluminescent method (Promega Corp.).

Viability Assays

For cytotoxicity studies, cells were rinsed with warm PBS and then placed in minimum essential medium (Invitrogen) containing 5.5 g/liter glucose, 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 μm cystine, containing the glutamate analog homocysteate (HCA; 5 mm). HCA was diluted from 100-fold concentrated solutions that were adjusted to pH 7.5. Viability was assessed by calcein-acetoxymethyl ester (AM)/ethidium homodimer-1 staining (live/dead assay) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) under fluorescence microscopy and the MTT assay (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) method (36). To evaluate the effects of the drugs on cytotoxicity, we added DFO, 3,4-DHB, compound A, and the HIF peptide simultaneously with HCA.

Immunofluoroscence Staining

Indirect labeling methods were used to determine the levels of HIF-1 protein in cortical neuron cultures. Dissociated cells from cerebral cortex were seeded onto poly-d-lysine-coated 8-well culture slides (BD Biosciences) and treated with Tat-HIF/ODD/mut, Tat-HIF/ODD/wt, and DFO overnight. Cells were washed with warm PBS and fixed at room temperature for 15 min with 4% paraformaldehyde. After washing, cells were incubated with blocking solution containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 5% goat serum in PBS for 1 h, followed by incubation with rabbit HIF-1 antibody (Upstate Cell Signaling, Lake Placid, NY) (1:100 dilution) overnight. After three washes with PBS, cells were incubated with rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) (1:200 dilution) and DAPI. The slides were washed three times with PBS and mounted with fluorochrome mounting solution (Vector Laboratories). Images were analyzed under a confocal fluorescence microscope (Zeiss LSM50, Germany). Control experiments were performed in the absence of primary antibody.

HIF Prolyl 4-Hydroxylase Activity Assay

The effects of Tat-HIF/ODD/mut, Tat-HIF/ODD/wt on purified HIF-prolyl 4-hydroxylase activity was analyzed by the method based on the hydroxylation-coupled decarboxylation of 2-oxo[1-14C]glutarate (37).

ICP-MS Analysis

Cortical neurons were plated and treated with 3,4-DHB, DFO, or compound A. Cells were collected, lyophilized, and stored at −80 °C until further testing. 50 μl of concentrated nitric acid (HNO3) (Aristar, BDH) was added to each lyophilized sample. Samples were allowed to digest overnight at room temperature followed by heating for 20 min at 90 °C using a heating block. Samples were diluted 1:25 with 1% HNO3 prior to analysis. Analysis was carried out on a Varian UltraMass ICP-MS instrument using operating conditions suitable for routine multielement analysis. The instrument was calibrated using 0, 10, 50, and 100 ppb of a certified multielement ICP-MS standard solution (ICP-MS-CAl2−1, AccuStandard). A certified internal standard solution containing 100 ppb of yttrium (89Y) as an internal control (ICP-MS-IS-MIX1−1, AccuStandard) was also used.

Calcein-AM Assay

Primary neurons were treated with the drugs 3,4-DHB, DFO, and compound A overnight as described previously. Fluorescence was measured from intact cells using an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 535 nm (38) after addition of 0.25 μm calcein-AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was added to cultured neuronal cultures for 30 min at room temperature.

IRP/IRE Binding Assay

Cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized, and collected. To separate membrane-bound organelles from cytosol, the cells were washed and homogenized in lysis buffer (10 mm/liter HEPES, pH 7.4, 40 mmol/liter KCl, 5% glycerol, 3 mmol/liter MgCl2, 0.1 mmol/liter EDTA, 1 mmol/liter dithiothreitol, 1 mmol/liter phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.1 g/liter leupeptin). Cells were sonicated to disrupt membranes. The homogenates were centrifuged for 5 min at 4 °C and 4000 × g to sediment nuclei. The resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 4 °C and 145,000 × g for 1 h, and the cytosolic fraction was collected. For preparation of RNA transcripts, the pGEM7Zf(+)-5′L containing the complete 5′-untranslated region of rat liver L-ferritin cDNA (39) was provided by R. S. Eisenstein (University of Wisconsin, Madison). The ferritin IRE RNA transcripts were prepared from maI-digested pGEM7Zf(+)-5′L containing 100 bases of 5′-untranslated region and 40 bases from the vector. RNA transcripts were synthesized from 1 μg of linearized plasmid DNA in the presence of 100 μCi of [α-32P]CTP (800 Ci/mmol), 12 μm unlabeled CTP, 0.5 mm of the three unlabeled nucleotides, 100 mm dithiothreitol, 20 units of T7 RNA polymerase in a 20-μl reaction volume. The reaction was carried out for 1 h at 37 °C. The yield of the transcript synthesized was determined by trichloroacetic acid precipitation. Under these conditions, the specific activity was ∼5 × 108 cpm/μg RNA. For the RNA band shift assay, 5 μg of protein for the cytoplasmic fractions were incubated with the synthetic radiolabeled IRE probe. The RNA-protein complexes were separated on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. The autoradiograms were scanned, and the resulting digital image was subjected to densitometric band analysis using the Labworks Analysis software (UVP Inc., Upland, CA). The results of the RNA band shift assays were expressed as active IRP binding from each treatment as a ratio of control.

RT-PCR

The levels of p21, enolase, VEGF, and β-actin were analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR by using the one-step RT-PCR kit ReddyMix version (Abgene). The following primers were used in this study: enolase 5′-GGTTCTCATGCTGGCAACAAGT-3′ (sense) and 5′-TAAACCTCTGCTCCAATGCGC-3′ (antisense) (GenBank™ accession number M012554); VEGF 5′-TGCAATGATGAAGCCCTGGA-3′ (sense) and 5′-TGCTATGCTGCAGGAAGCTCA-3′ (anti-sense) (GenBank™ accession number M32167); p21 5′-ATGTCCGATCCTGGTGATGT-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACTTCAGGGCTTTCTCTTGC-3′ (antisense) (GenBank™ accession number U24174); β-actin 5′-CCTCATGAAGATCCTGACCG-3′ (sense) and 5′-TGCCAATAGTGATGACCTGG-3′ (antisense) (GenBank™ accession number NM007393).

In Vivo Experiments

All experimental procedures were approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals and meet the standards of the Federal and State reviewing organizations.

Animal Preparation and Monitoring

Eleven adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 11) weighing 250−280 g (Charles River Breeding Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were operated on. Nine rats survived and were analyzed for this study. Mortality was 18% (2:11) and occurred equally in the groups of animals (one rat in each group). Death occurred during the first 20 h postoperatively. Animals were allowed free access to food and water before and after surgery. Briefly, rats were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of 400 mg/kg chloral hydrate followed 45 min later by a maintenance intraperitoneal infusion at a rate of 120 mg/kg/h using a butterfly needle set. The animals were free breathing. Their body temperatures were kept stable at 36.5 ± 0.5 °C using a feedback-regulating heating pad and a rectal probe (Harvard Apparatus, MA). The right femoral artery was cannulated for measurement of arterial blood gases, glucose, and mean arterial blood pressure. These physiological parameters were monitored before and after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). In addition, laser Doppler flowmetry (Moor Instruments, Devon, UK) was used to monitor the regional cerebral blood flow through a burr hole 2 mm in diameter created in the right parietal bone (2 mm posterior and 6 mm lateral to bregma).

Surgery

All rats were subjected to right MCAO. Under the operating microscope, the right common carotid artery was exposed through a midline incision in the neck. A 4−0 nylon suture with its tip rounded by heating over a flame and subsequently coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma) was introduced into the external carotid artery and then advanced into the internal carotid artery for a length of 18−19 mm from the bifurcation. This method placed the tip of the suture at the origin of the anterior cerebral artery, thereby occluding the MCA. The placement of the suture tip was monitored by laser Doppler flowmetry measurements of regional cerebral blood flow. MCAO caused a sharp drop in regional cerebral blood flow to less than 30% of preischemic base line. The suture was left in place, and the animals were allowed to awaken from the anesthesia following closure of the operation sites.

Drug Administration

3,4-DHB was dissolved in ethanol (vehicle) for a total volume of 100 μl and was administered intraperitoneally to animals (n = 6) at a dose of 180 mg/kg of body weight. 3,4-DHB was administered 6 h before MCAO. Compound A was administered to animals (n = 9) at a dose of 100 mg/kg of body weight using a gavage 6 h before the MCAO. The control animals received an equivalent volume of the vehicle (ethanol for 3,4-DHB and carboxymethylcellulose for compound A) on a similar administration schedule.

Infarct Measurement

24 h after MCAO, the animal were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) and xylazine (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) and decapitated. The brain was rapidly removed, sliced into seven 2-mm coronal sections using a rat matrix (RBM 4000C, ASI Instrument Inc., Warren, MI), and stained according to the standard 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) method (40, 41). Each slice was drawn using a computerized image analyzer (Scion Corp.). The calculated infarction areas were then compiled to obtain the infarct volumes per brain (in mm3). Infarct volumes were expressed as a percentage of the contralateral hemisphere volume to compensate for edema formation in the ipsilateral hemisphere (42, 43).

RESULTS

Low Molecular Weight HIF Prolyl 4-Hydroxylase Inhibitors Stabilize HIF and Activate HIF-dependent Gene Expression in Embryonic Rat Cortical Neurons

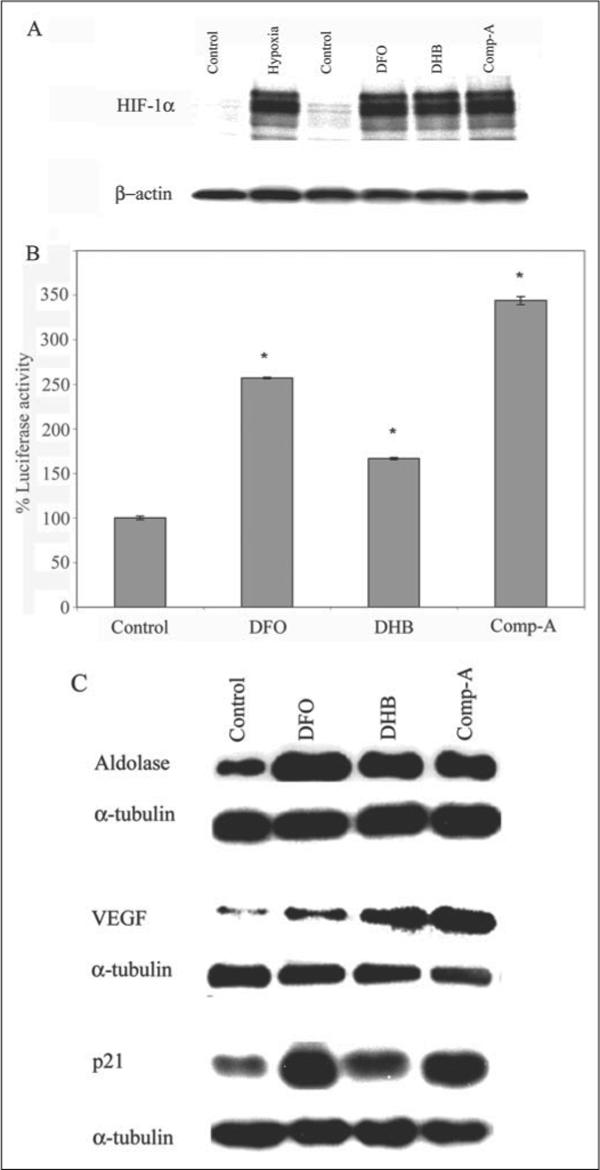

Oxidative glutamate toxicity in immature cortical neurons results from the ability of glutamate to inhibit competitively the uptake of cystine via its plasma membrane transporter (system Xc–) (44). Inhibition of cystine uptake into the cell via system Xc– results in depletion of intracellular cysteine, the rate-limiting precursor of glutathione synthesis. Cyst(e)ine deprivation thus leads to depletion of the major cellular antioxidant glutathione, an imbalance in cellular oxidants and antioxidants and oxidative stress-induced death. Indeed, a host of agents with known antioxidant capacity can completely abrogate glutamate toxicity in this paradigm. To determine whether prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibition is sufficient to prevent oxidative glutamate toxicity, we treated immature cortical neurons with established, structurally diverse, low molecular weight inhibitors of the prolyl 4-hydroxylases, DFO, 3,4-DHB, and compound A. DFO, 3,4-DHB, and compound A were selected for testing because their mechanisms of prolyl hydroxylase inhibition are believed to be distinct. 3,4-DHB has been shown previously to be an inhibitor of collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylases with respect to the 2-oxoglutarate and ascorbate cofactors and to be neutral with respect to Fe2+ (45). By contrast, the ability of DFO to inhibit recombinant prolyl 4-hydroxylase activity can be overcome by addition of exogenous iron to the test tube (45). Compound A has been reported to be an inhibitor of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases (30). Immunoblotting using a specific antibody to HIF-1α established that, like hypoxia, all of these agents (100 μm DFO, 10 μm dihydroxybenzoic acid, 40 μm compound A) stabilize HIF-1α but do so in normoxic neurons (Fig. 1A). Stabilization of HIF-1α by each of these low molecular weight compounds was associated with significant transactivation of a reporter gene driven by hypoxia-response elements (boldface in the sequence) from the promoter region of the enolase gene (5′-ACGCTGAGTGCGTGCGGGACTCGGAGTACGTGACGGA-3′) (Fig. 1B; p < 0.05). A control reporter gene without these response elements or one with the hypoxia-response elements mutated were not up-regulated by these compounds (not shown).

FIGURE 1. Structurally diverse, low molecular weight prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibitors stabilize HIF-1 protein, enhance activity of a hypoxia-response element-driven luciferase reporter, and increase the expression of established HIF-regulated genes in embryonic cortical neurons.

A, cortical neuronal cultures (1 day in vitro (DIV)) were treated with a vehicle control (C, Me2SO (0.01%)), DFO (100 μm), 3,4-DHB (10 μm), or compound A (Comp-A; 40 μm) or exposed to 1% hypoxia (H) overnight. Proteins from cell lysates were separated using gel electrophoresis and immunodetected using an antibody against HIF1-α. β-Actin was monitored as a loading control. B, cortical neuronal cultures (1 DIV) were infected with an adenovirus harboring the hypoxia-response elements from the enolase promoter linked to a luciferase reporter (multiplicity of infection = 100). Parallel infection with adenovirus containing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) indicated reproducible infection efficiencies of ∼30−40%. 24 h following infection with adeno-HRE-luciferase, cortical neuronal cultures were treated with a vehicle control (C), DFO (100 μm), 3,4-DHB (10 μm), or compound A (40 μm). Lysates from each treatment group were generated, and luciferase activity was measured. Graph depicts mean percentage luciferase activity (compared with control) ± S.E. calculated from three separate experiments for each group (* denotes p < 0.05 by ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls tests for DFO, 3,4-DHB, or compound A). C, DFO (100 μm), 3,4-DHB (10 μm), and compound A (40 μm) increase expression of established HIF target genes, aldolase, VEGF, or p21waf1/cip1 in cultured cortical neurons as compared with vehicle-treated control. Immunoblots are representative examples of three experiments.

To verify that increased reporter activity was reflected in increased protein expression, immunoblotting was performed to monitor levels of aldolase, VEGF, and p21waf1/cip1, known HIF-1-regulated genes (33). α-Tubulin was used as a control because its transcriptional regulation appears to be HIF-independent. As expected, DFO, 3,4-DHB, and compound A all increased protein levels of aldolase, VEGF, and p21waf1/cip1 but not α-tubulin (Fig. 1C). Taken together these results established that like non-neuronal cells, DFO, 3,4-DHB, and compound A can all inhibit HIF prolyl 4-hydroxlyases, stabilize HIF, and lead to the increased transcription of established HIF-dependent genes.

Structurally Diverse Inhibitors of the HIF Prolyl 4-Hydroxylases Can Abrogate Oxidative Stress-induced Death in Cortical Neurons

To determine whether structurally diverse inhibitors of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases can abrogate death because of oxidative glutamate toxicity at concentrations at which they activate HIF, we added these compounds at the time of exposure to glutamate (not shown) or the glutamate analog homocysteate (HCA, 5 mm). As expected, all three agents significantly prevented oxidative stress-induced death, suggesting that HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases are a target for protection from oxidative death in neurons (Fig. 2, A and B). The number of live and dead cells in the dish were monitored using several methods, including MTT reduction (Fig. 2A), visualization by phase contrast microscopy (not shown), and calcein labeling or ethidium homodimer labeling to tag live cells or dead cells, respectively (Fig. 2, B–I). In all cases, the results obtained were similar.

FIGURE 2. Structurally diverse, low molecular weight prolyl 4-hydrdoxylase inhibitors abrogate oxidative glutamate toxicity in embryonic cortical neuronal cultures.

A, the glutamate analog HCA (5 mm) was added to cortical neuronal cultures (1 DIV). In parallel, DFO (100 μm), 3,4-DHB (10 μm), and compound A (Comp-A) (40 μm) were added with and without HCA. Twenty four hours later, cell viability was determined using the MTT assay. Graph depicts mean ± S.E. for three experiments performed in triplicate (* denotes p < 0.05 from HCA-treated cultures by ANOVA and Student-Newman Keuls tests for control, DFO, 3,4-DHB, or compound A). B–I, live/dead assay of cortical neuronal cultures (2 DIV). Live cells are detected by uptake and trapping of calcein-AM (green fluorescence). Dead cells fail to trap calcein but are freely permeable to the highly charged DNA intercalating dye, ethidium homodimer (red fluorescence). B, control. C, HCA (5 mm). D, DFO (100 μm). E, DFO + HCA. F, 3,4-DHB (10 μm). G, 3,4-DHB + HCA. H, compound A (40 μm). I, compound A + HCA.

The absolute level of protection from oxidative death by the three compounds did not seem to correlate with their transcriptional efficacy. For example, compound A is the most effective in stimulating HRE-driven luciferase activity and VEGF protein levels; and despite significantly preventing oxidative death, it also induces a small but reproducible basal toxicity in the cultures (Fig. 2H). These findings suggest that although HIF-dependent transcription is a good marker of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibition, other factors besides HIF transcriptional activity may contribute to neuroprotection by agents that inhibit HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases. Of course, one cannot rule out other prolyl 4-hydroxylase-independent effects of the drugs on viability as an explanation for the quantitative differences in neuroprotection from the oxidative death we observed between DFO, DHB, and compound A

Some but Not All Prolyl 4-Hydroxylase Inhibitors Tested Reduce Total Cellular Iron in Embryonic Rat Cortical Neurons

HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases are iron-dependent enzymes. To verify that at least one of the PH inhibitors tested does not alter iron levels in cortical neurons, we monitored total iron levels by inductively coupled plasma mass spec-trometry. This technique allowed us to perform sensitive analysis of chelatable and nonchelatable metals. Total cellular iron was decreased by overnight incubation with DFO (100 μm) and compound A (40 μm) but not 3,4-DHB (10 μm) treatment in cultured neurons (TABLE ONE). This does indicate some ability to extract iron or prevent its uptake, in this case, from cells and perhaps suggests the possibility of direct iron chelation. These findings are in agreement with prior in vitro studies demonstrating that DFO inhibits prolyl 4-hydroxylase activity by binding its critical iron cofactor (46), whereas 3,4-DHB inhibits prolyl 4-hydroxylases by displacing 2-oxoglutarate or ascorbate and not iron (45). The effect of DFO and compound A showed selectivity for the trace metal iron as neither these agents nor 3,4-DHB had any effect on total zinc in rat neuronal cultures (TABLE ONE). Taken together, these results are consistent with the notion that DFO and compound A act to inhibit the prolyl hydroxylases by removing the Fe2+ cofactor or binding to it within the enzyme, whereas 3,4-DHB inhibits prolyl 4-hydroxylase activity by iron-independent mechanisms.

TABLE ONE. Total zinc and iron levels in cultured cortical neurons nontreated (control) or treated with DFO (100 /im) 3,4-DHB (10 /im), or compound A (40 /m) measured by ICP-MS.

Values are shown as mean ± S.E. percent relative to control levels that were arbitrarily designated as 100%. Levels of individual metals in a particular culture were normalized to protein.

| Control | DFO | 3,4-DHB | Compound A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc (%) | 100 | 93.6 ± 2.8 | 120.3 ± 2.9 | 110.7 ± 2.2 |

| Iron (%) | 100 | 68.8 ± 9.5a | 93.3 ± 3.1 | 70.04 ± 2.4a |

p < 0.05.

A Peptide Inhibitor of the HIF Prolyl 4-Hydroxylases Delivered into Neurons Using an HIV Tat Protein Transduction Domain Activates HIF-dependent Gene Expression and Prevents Oxidative Death in Vitro

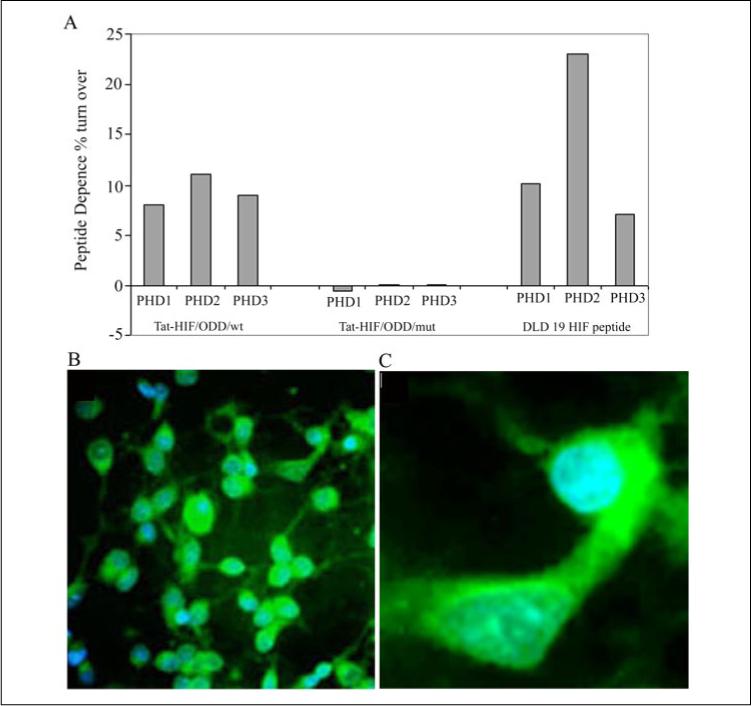

Low molecular weight inhibitors of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases were initially identified via a search for inhibitors of the collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylases. The collagen prolyl hydroxylases catalyze the formation of 4-hydroxyproline in collagen and certain other proteins that possess collagen-like sequences by hydroxylating prolines in X-Pro-Gly motifs (47). Hydroxyprolines facilitate the formation of stable triple helical collagen. Unlike HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases, which are believed to be cytoplasmic or nuclear (48), the collagen prolyl hydroxylase is a soluble endoplasmic reticulum luminal protein (47). However, like HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases, collagen hydroxylases employ ferrous ions, 2-oxoglutarate, molecular oxygen, and ascorbate as cofactors. Thus by disrupting one or more of these cofactors, DFO, 3,4-DHB, and compound A could inhibit collagen prolyl hydroxylases, HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases, and other 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases in the intact cell. In order to determine whether HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases are relevant for protection from glutathione depletion-induced death by DFO, 3,4-DHB, and compound A, we used the following strategy. Myllyharju and co-workers (37) recently described the identification of a 19-amino acid peptide that is able to act as a substrate for all the human HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases (Km = 5−10μm). This peptide contains part of the oxygen-dependent domain including the C-terminal hydroxylation site of human HIF at proline 564 (DDLDEMLAPYIPMDDDFQL; boldface P indicates proline 564). We hypothesized that such a peptide delivered into neurons could act as a competitive inhibitor of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases while leaving other 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases unperturbed. Indeed, previous studies have shown that this peptide is not a substrate for recombinant collagen prolyl hydroxylases (30). Phylogenetic conservation (from worms to humans) of the critical residues from HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases that serve as ligands for Fe2+ and 2-oxoglutarate suggested that a peptide deemed to be a potent and effective substrate of all three known human HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases would also act to competitively inhibit HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases expressed in rat cortical neurons (46).3 Our HIF/ODD/wt peptide and a peptide control with mutation of both prolines to alanine (HIF/ODD/mut; DDLEMLAAYIAMDDDFQL) were rendered cell-permeant by fusing each of these peptides to the cell membrane transduction domain of the human immunodeficiency virus, type 1 (HIV-1), Tat protein (YGRKKRRQRR) to obtain two 30-amino acid peptides Tat-HIF/ODD/wt and Tat-HIF/ODD/mut (49). To verify that the addition of Tat to the 19-amino acid HIF peptide does not alter its specificity for the recombinant HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases, we compared activities of the Tat-HIF/ODD/wt, Tat-HIF/ODD/mut, and the native HIF/ODD/wt. We employed a commonly used assay for the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase that is based on the hydroxylation of a synthetic substrate and the associated measurement of the radioactivity of 14CO2 formed during the hydroxylation coupled decarboxylation of 2-oxo[1-14C]glutarate. This assay confirmed that the Tat-HIF/ODD/wt peptide but not the Tat-HIF/ODD/mut is a substrate with similar activity to the isoforms of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases as a standard synthetic 19-amino acid peptide with a sequence around the C-terminal hydroxylation site of HIF-1α (DLD 19 HIF peptide (HIF/ODD/wt), Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3. A cell-permeant peptide inhibitor of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases, but not a mutant control, is a substrate for purified, recombinant HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases 1, 2, and 3 isoforms.

A, Tat-HIF/wt peptide (100 μm, composed of the oxygen-dependent domain, including the C-terminal hydroxylation site of human HIF-1α at proline 564 (DDLDEMLAPYIPMDDDFQL; boldface P indicates proline 564) linked to a Tat protein transduction domain YGKKRRQRRR) but not a corresponding peptide with the C-terminal proline hydroxylation site of HIF-1α-mutated (Tat-HIF/mut, DLDLEMLAAYIAMDDDFQL; boldface A indicates the mutation site) acts as a substrate for the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases and releases [14C]CO2 from α-ketoglutarate. DLD 19 HIF peptide, composed of the C-terminal hydroxylation site of human HIF-1α at proline 564 without the TAT sequence was used as a positive control. B, representative low magnification image (×40) of cortical neurons treated with a FITC-labeled Tat-HIF/wt peptide (100 μm)(green fluorescence) and the DNA intercalating dye, DAPI, to label nuclei (blue fluorescence). Note all blue nuclei have green fluorescence in the cytoplasm indicating a high efficiency of transduction of the peptide into cells. C, a representative high magnification image (×60) of cortical neurons treated with FITC-Tat-HIF/wt peptide (100 μm) and labeled with the DNA intercalating dye DAPI.

To evaluate the ability of our Tat-HIF/ODD peptides to be delivered to cortical neurons efficiently and without toxicity, we conjugated the chromophore fluorescein isothiocyanate to the Tat-HIF/ODD/wt peptide. Tat-HIF/ODD/wt FITC peptides (10 μm) were bath applied to rat cortical neuronal cultures from embryonic day 17 rat embryos. These cultures are ∼90% neurons after 1 day in vitro (35). The balance of the cells in the culture is glial in origin. Twenty four hours after addition of the peptide to the bathing medium, the level of intracellular accumulation of the peptide was monitored by fluorescence microscopy. In every field examined (>10), each cell nucleus, identified by DNA intercalating chromophore DAPI, was found to be associated with fluorescein label in its cell bodies and processes reflecting the uptake of the Tat-HIF/ODD/wt FITC peptide (Fig. 3, B and C). Similar high efficiency transduction was observed when cortical neuronal cultures were incubated with the Tat-HIF/ODD/mut FITC peptide (not shown). In parallel, viability measurements verified that the Tat-HIF/ODD peptides do not negatively alter basal viability in our cortical neuronal cultures (not shown).

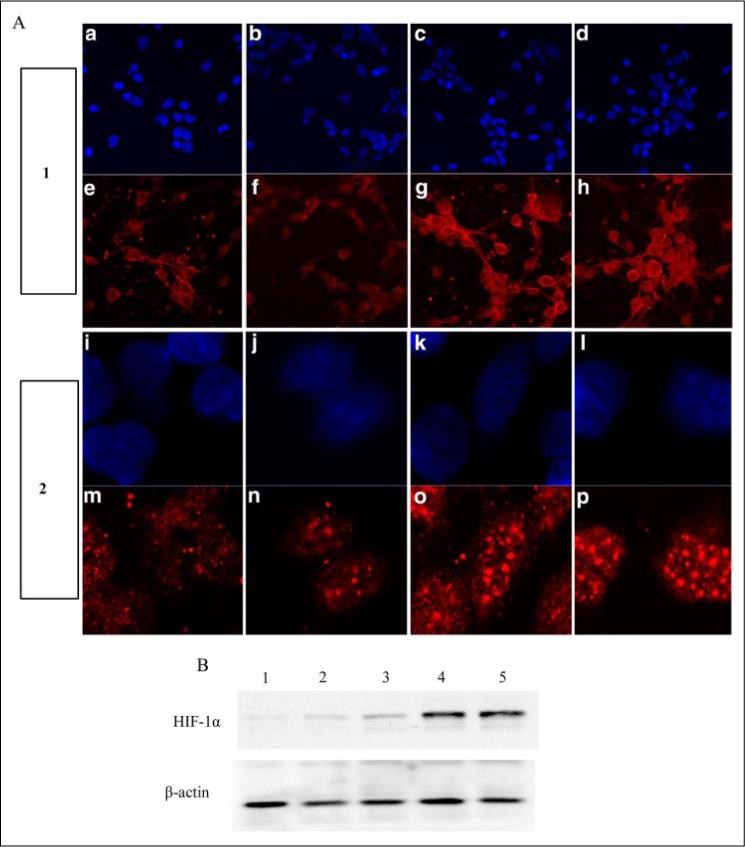

To determine whether the Tat-HIF/ODD/wt peptide stabilizes HIF-1α in cortical neurons, we performed immunocytochemical staining with an antibody to HIF-1α (Fig. 4, e–h, ×20; m–p, ×60) using in all cases a rhodamine-labeled secondary antibody that fluoresces red. In parallel, the same cultures were treated with the nuclear stain DAPI, which fluoresces blue (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) (Fig. 4, a–d, ×20; i–l, ×60). The HIF-1α antibody fluorescence confocal images (×20) confirmed that the Tat-HIF/ODD/wt peptide increases HIF-1α staining in cortical neurons (Fig. 4g), but the Tat-HIF/ODD/mut peptide does not (Fig. 4f). Addition of vehicle was used as a negative control (Fig. 4e), and DFO was used as a positive control (Fig. 4h). High magnification confocal microscopic images of HIF-α antibody fluorescence from the nuclei of cortical neurons (×60) (Fig. 4o) and immunoblot analysis of nuclear extracts using the same HIF-1α antibody (Fig. 4B, lanes 3 and 4) verified that the increases in HIF-1α levels induced by Tat-HIF/ODD/wt are cytoplasmic and nuclear.

FIGURE 4. The peptide inhibitor of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases, but not a mutant control, stabilizes HIF protein in primary cortical neurons.

A, Tat-HIF/mut peptide (f and n), Tat-HIF/wt peptide (100 μm) (g and o), DFO (100 μm) (h and p), or vehicle control (e and m) were added to the bathing medium of cortical neurons. Panel 1 represents lower magnification (×20), and panel 2 represents higher magnification (×60). Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and immunostained for HIF-1α (red) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” DAPI staining was performed to label nuclei (blue) (a–d, ×20; and i–l, ×60). B, immunoblot analysis with an antibody to HIF-1α in cell lysates from nontreated (lane 1) or after treatment with Tat-HIF/mut peptide (100 μm, lane 2), Tat-HIF/wt peptide (20 μm, lane 3; 100 μm, lane 4), or DFO (100 μm, lane 5, positive control).

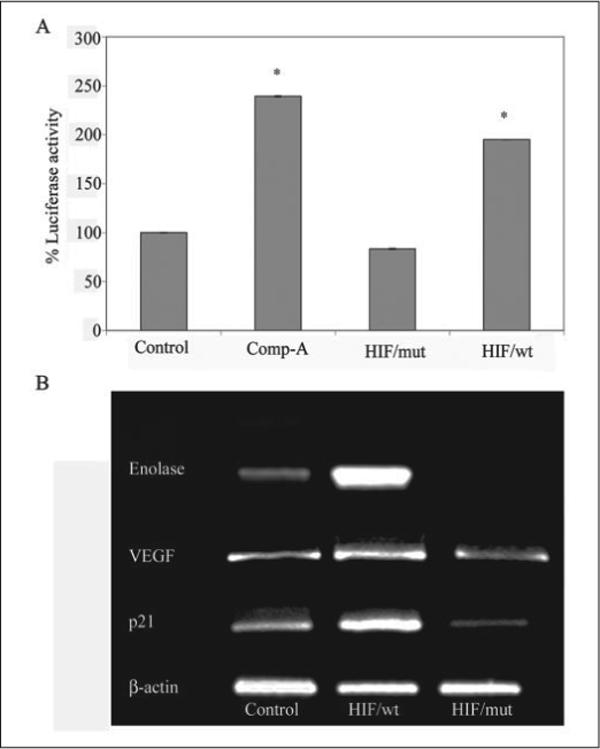

To confirm that stabilization of HIF-1α is associated with activation of HIF-dependent gene expression, we monitored the levels of a luciferase reporter gene that is regulated by a hypoxia-response element found in the enolase gene promoter. As expected, we found that addition of Tat-HIF/ODD/wt peptide significantly enhanced levels of a hypoxia-response element-regulated reporter gene in a concentration-dependent manner (not shown). The level of induction of the HIF-dependent reporter gene by 100 μm Tat-HIF/ODD/wt peptide was similar to that stimulated by 40 μm compound A, a low molecular weight inhibitor of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase (Fig. 5A). By contrast, 100 μm Tat-HIF/ODD/mut peptide with proline 564 and its adjacent proline mutated to alanine did not induce the HIF-dependent reporter gene. Because the unhydroxylatable peptide did not increase target gene expression, it does not likely serve as a competitive inhibitor of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases. To verify that the changes in the HIF-dependent reporter gene reflect changes in endogenous HIF-dependent genes, we monitored enolase, p21waf1/cip1, and VEGF by RT-PCR. β-Actin was measured as a control (Fig. 5B). As expected, the Tat-HIF/ODD/wt peptide increased levels of enolase, p21waf1/cip1, and VEGF message but did not alter levels of β-actin. Accordingly, we found that the Tat-HIF/ODD/mut did not affect levels of p21waf1/cip1 or β-actin and actually diminished the basal levels of enolase and VEGF, two known HIF-dependent genes. Real time PCR was utilized to examine quantitatively the difference in message levels between the HIF/ODD/wt- and HIF/ODD/mut-treated neurons. These studies confirmed the ability of the wild type but not the mutant peptide to increase HIF-dependent gene expression (VEGF, 1.46 ± 0.218-fold induction (wt/mut); erythropoietin, 1.84 ± 0.068-fold induction (wt/mut); p21waf1/cip1, 1.52 ± 0.16-fold induction). Taken together, these results establish that the Tat-HIF/ODD/wt peptide can be delivered to neurons and can enhance the transcriptional activity of well characterized HIF target genes. By contrast, a Tat/HIF/ODD/mut, in which the conserved proline hydroxylation site (proline 564) and an adjacent proline have been mutated to alanine, does not up-regulate an HIF-dependent reporter gene or endogenous HIF-regulated genes (e.g. enolase, p21waf1/cip1, or VEGF).

FIGURE 5. A peptide inhibitor of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases, but not a mutant control, induces expression of established HIF-dependent genes.

A, Tat-HIF/wt peptide (100 μm) but not a corresponding peptide with the C-terminal proline hydroxylation site of HIF-1α mutated (Tat-HIF/mut, 100 μm) significantly enhances the activity of a hypoxia-response element-driven reporter in cortical neurons (* corresponds to p < 0.05 compared with control by paired t test). Note that the Tat-HIF/wt peptide induces HIF reporter activity to a similar extent as the low molecular weight inhibitor, compound A (Comp-A) (40 μm). B, RT-PCR using specific primers to determine the mRNA level of established HIF target genes, enolase, p21waf1/cip1, or VEGF in vehicle-treated (control) or in neuronal cultures treated with Tat-HIF/wt peptide (100 μm) and Tat-HIF/mut (100 μm) overnight. β-Actin was monitored as a housekeeping gene.

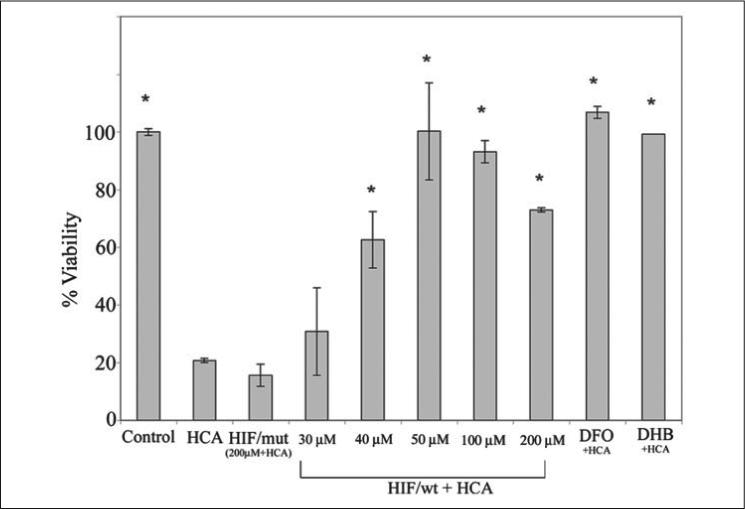

To test whether Tat-HIF/ODD/wt, a peptide inhibitor of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases, can prevent oxidative neuronal death in cortical neurons induced by the glutamate analog, HCA, we applied the peptides 24 h prior to the addition of HCA. Addition of Tat-HIF/ODD/wt peptide but not its mutant control (Tat-HIF/ODD/mut) protected cortical neurons from oxidative glutamate (glutathione depletion-induced) toxicity in a concentration-dependent manner as assessed by MTT assay (Fig. 6). The morphology of the neurons that were protected from oxidative glutamate toxicity by Tat-HIF/ODD/wt was indistinguishable from the morphology of control neurons as assessed by phase contrast microscopy or calcein/ethidium homodimer staining (not shown). These results suggest that inhibition of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases is sufficient to prevent oxidative neuronal death in cortical neurons in vitro and argue that 3,4-DHB, DFO, and compound A are influencing cell viability by inhibiting HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases rather than a distinct 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase.

FIGURE 6. A cell-permeant peptide inhibitor of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases, but not a mutant control, prevents oxidative glutamate toxicity.

The glutamate analog, HCA (5 mm) was added to cortical neurons (1 DIV) with or without Tat-HIF/wt peptide (30, 40, 50, 100, and 200 μm), Tat-HIF/mut peptide (200 μm), DFO (100 μm), and 3,4-DHB (10 μm). Twenty four hours later cell viability was determined using the MTT assay. Graph depicts mean ± S.E. for three experiments performed in triplicate (* denotes p < 0.05 from HCA-treated cultures by ANOVA and Student-Newman Keuls tests for control, Tat-HIF/wt, Tat-HIF/mut, DFO and 3,4-DHB).

Low Molecular Weight Inhibitors of HIF Prolyl 4-Hydroxylases Reduce Neuronal Damage Induced by Permanent Focal Ischemia in Vivo

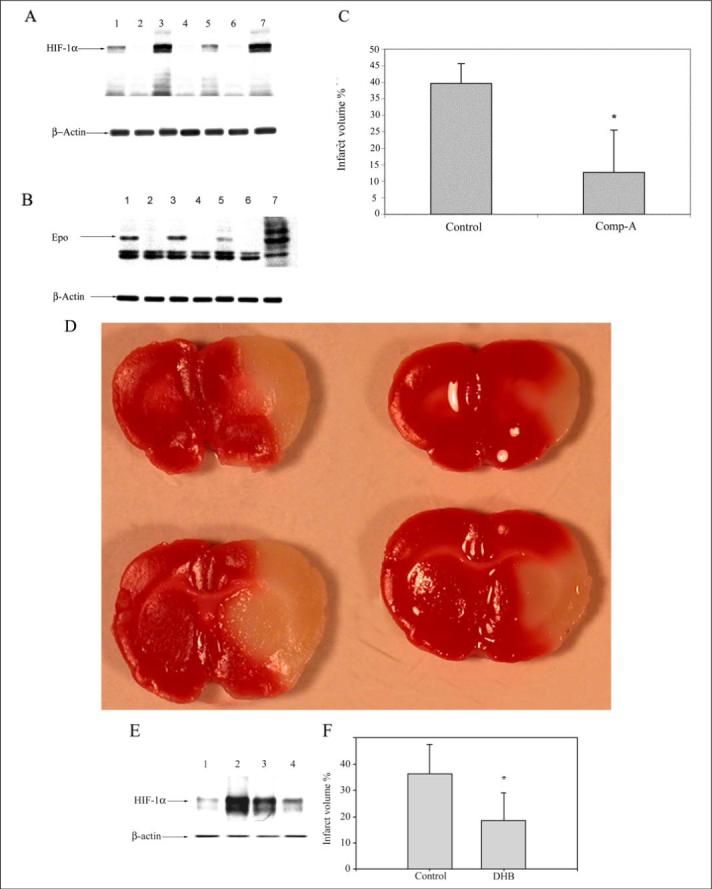

Oxidative stress is an established mediator of neuronal loss in cerebral ischemia (50). Prior studies have also demonstrated that the putative antioxidant DFO can ameliorate metabolic failure in dogs subjected to cerebral ischemia or induce ischemic tolerance in neonatal or adult rodents (51-53). Some of these studies have suggested that the effects of DFO may be related to HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibition. However, these studies did not provide any experimental support for the notion that HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases are a target for ischemic neuroprotection by DFO. The protective effects of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibitors in preventing oxidative neuronal death in vitro herein (Figs. 1-6) provided additional rationale for testing these agents in an in vivo model of cerebral ischemia. We therefore examined the ability of 3,4-DHB or compound A to prevent neuronal damage in response to permanent focal ischemia. In this model, a filament is placed permanently into the distal aspect of the internal carotid artery to occlude the origin of the middle cerebral artery (43). After 24 h of occlusion, there is significant infarction in the hemisphere ipsilateral to the occlusion; few animals survive beyond this time point. We first examined a range of concentrations of 3,4-DHB and compound A, and we determined that administration of 100 mg/kg of compound A (via gavage) or 160 mg/kg of 3,4-DHB (via intraperitoneal administration) was effective at stabilizing the HIF protein and inducing an increase in some HIF-dependent genes, including erythropoietin in lysates from brains of individual vehicle-treated or HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibitor-treated brains (Fig. 7, A, B, and E). The stabilization of HIF in brain by compound A was observed within 3 h (Fig. 7A, whereas the stabilization of HIF by 3,4-DHB was observed within 6 h of administration (Fig. 7E). Inhibition of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases was associated with marked reduction in infarct volume as measured histologically by TTC staining by compound A (67%, Fig. 7, C and D) or by 3,4-DHB (46%, Fig. 7F). Protection by these agents could not be attributed to the effects of these agents on body temperature, plasma glucose levels, plasma pH, or blood flow (TABLE TWO, compound A and 3,4-DHB). Together, these findings suggest that HIF prolyl 4-hydroxlyases are a target for protection in stroke and suggest that the salutary effects of these treatments in cerebral ischemia are due in part to HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibition.

FIGURE 7. Structurally diverse, low molecular weight prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibitors stabilize HIF protein, increase the expression of established HIF-regulated genes, and reduce infarct volume induced by permanent focal ischemia in vivo.

Three rats were treated in parallel with compound A (lanes 1, 3, and 5) with a dose of 100 mg/kg of body weight (by gavage) 6 h prior to MCAO. As controls, three rats (lanes 2, 4, and 6) received equal volume of vehicle (0.5% carboxymethylcellulose) in a blinded study. Whole brain lysates from individual animals in the treated (n = 9) (lanes 1, 3, and 5) and control group (n = 5) (lanes 2, 4, and 6) were separated using gel electrophoresis and immunodetected using an antibody against HIF1-α (A) and erythropoietin (Epo) (B). Whole brain lysates of 1% hypoxia-exposed animals were used as a positive control for HIF-1α and erythropoietin (lane 7). β-Actin was monitored as a housekeeping gene. C, histologically measured infarct volume of brains of compound A (Comp-A) (n = 9) and vehicle-treated animals (n = 5) after TTC staining. The values are shown as % infarct volume relative to total brain volume (* = p < 0.05 by paired t test). D, representative pictures of vehicle-treated (left) and compound A-treated (right) brains showing infarctions. E, animals were treated with 3,4-DHB (n = 6) (lanes 2 and 3) with a dose of 180 mg/kg of body weight (intraperitoneally) 6 h prior to MCAO. Control animals (n = 5) (lanes 1 and 4) received equal volume of vehicle (ethanol, intraperitoneally) in a blinded study. Whole brain lysates were separated using gel electrophoresis and immunodetected using an antibody against HIF1-α. β-Actin was monitored as a housekeeping gene. F, histologically measured infarct volume of brains of 3,4-DHB (n = 6) and vehicle-treated animals (n = 5) after TTC staining. The values are shown as % infarct volume relative to total brain volume (* = p < 0.05 by paired t test).

TABLE TWO. Physiologic data obtained from both control and treated animal groups are represented as means ± S.E.

The following abbreviations are used: Hct, hematocrit; Glu, blood glucose; MABP, mean arterial blood pressure; HR, heart rate. Animals were maintained at 36.5 ± 0.5 °C (rectal temperature). There was no statistically significant difference between control and treated groups in both pre- and post-MCAO categories.

| Physiological parameters | Pre-ischemia | Post-ischemia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | Compound A group | Control group | Compound A group | |

| Compound A | ||||

| pH | 7.35 ± 0.05 | 7.36 ± 0.02 | 7.32 ± 0.03 | 7.34± 0.03 |

| PCO2 (mm Hg) | 33 ± 5 | 35± 4 | 30± 2 | 32± 3 |

| PO2 (mm Hg) | 99 ± 12 | 100 ± 10 | 95 ± 10 | 100± 10 |

| Hct (%) | 40 ± 4 | 40± 3 | 38± 4 | 40± 4 |

| MABP (mm Hg) | 91 ± 12 | 89 ± 18 | 95 ± 12 | 88 ± 23 |

| 3,4-DHB | ||||

| pH | 7.35 ± 0.05 | 7.33 ± 0.06 | 7.35 ± 0.06 | 7.33 ± 0.06 |

| PCO2 (mm Hg) | 34± 2 | 34± 2 | 34.2 ± 2 | 35± 2 |

| PO2 (mm Hg) | 93 ± 3 | 95± 4 | 93± 3 | 96± 3 |

| Hct (%) | 42 ± 1 | 43± 2 | 41± 2 | 43± 2 |

| MABP (mm Hg) | 93 ± 3 | 92 ± 3 | 94 ± 4 | 93 ± 4 |

DISCUSSION

Prior studies from our laboratory correlated the protective effects of iron chelators in an in vitro model of oxidative stress with their ability to stabilize HIF-1 and activate HIF-dependent genes (28). These findings supported the hypothesis that iron chelators not only prevent neuronal injury by inhibiting hydroxyl radical formation via Fenton chemistry but also via inhibition of the iron-dependent HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases that regulate HIF stability. In this study we utilize low molecular weight or peptide inhibitors of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases in vitro and in vivo to define this family of enzymes as targets for neuroprotection in the central nervous system, and also to suggest that the inhibition of these enzymes is one way in which these treatments exert their salutary effects against oxidative stress. The HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases require iron, 2-oxoglutarate, oxygen, and ascorbate as cofactors. Two of the low molecular weight agents we tested, DFO and compound A, appear to inhibit prolyl 4-hydroxylases by removing the iron cofactor. Indeed, both agents reduced total iron in embryonic rat cortical neurons by 30% after 24 h (TABLE ONE). Despite these measurable changes in total iron, we could not detect statistically significant changes in IRP-IRE binding or calcein fluorescence (independent measures of the labile iron pool) in cortical neuronal cultures treated with DFO or compound A (not shown). As some of the proteins established to play a role in iron homeostasis are regulated by prolyl hydroxylases (e.g.IRP2 (50)) or HIF (e.g. transferrin receptor (51)), the lack of change in IRP-IRE binding raises the intriguing possibility that prolyl hydroxylase inhibition is a compensatory response to cellular iron deficiency that permits the labile iron levels to remain normal despite the presence of a chelator that reduces total iron. Given the oral availability of compound A (DFO cannot be taken orally) and its efficacy against oxidative stress in vitro and permanent focal ischemia in vivo, the findings also suggest that this molecule may have advantages over DFO as a therapeutic agent for acute and chronic neurological conditions where DFO has been shown to be effective (24, 26).

Prior studies in non-neuronal systems have suggested that 3,4-DHB also stabilizes HIF via its ability to bind iron (54, 55). However, several observations herein argue against this possibility in embryonic rat cortical neurons. First, the concentrations of 3,4-DHB (10 μm) required to stabilize HIF and protect cortical neurons were not found to bind iron in one study where 3,4-DHB was reported to act as an iron chelator (54). Second, in vitro studies using recombinant collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase showed that 3,4-DHB inhibitory actions occur via the displacement of 2-oxoglutarate and ascorbate but not iron (45). Third, total iron levels and IRP-IRE binding in 3,4-DHB-treated neurons were unchanged as compared with controls (TABLE ONE and data not shown). Despite the inability of 3,4-DHB to bind iron, it was still capable of stabilizing HIF, activating HIF-dependent gene expression, and protecting cortical neurons from oxidative stress in vitro and cerebral ischemia in vivo (Figs. 1 and 4). Thus, inhibition of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases is the likely relevant consequence of treatment with 3,4-DHB, compound A, and DFO. For chronic neurodegenerative conditions where daily use of an HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibitor that chelates iron may result in restless legs syndrome (56) or anemia (57), the use of an HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibitor that targets 2-oxoglutarate or ascorbate rather than iron has potential advantages.

The 2-oxoglutarate-dependent prolyl 4-hydroxylases are a family of iron- and ascorbate-dependent enzymes that include not only HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases but collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylases as well. DFO, 3,4-DHB, and compound A would be expected to inhibit both subfamilies of enzymes, although recent studies suggest the Ki of these agents for collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylases and HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases may be distinct (37). In an attempt to develop a more specific inhibitor of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases, we conjugated a 19-amino acid C-terminal portion of the oxygen-dependent degradation domain of HIF to an 11-amino acid protein transduction domain from the HIV-tat protein. Recent studies have shown that this 19-amino acid peptide (ODD/wt) but not shorter peptides bind all three human isoforms of the HIF-prolyl 4-hydroxylases with high affinity and are efficiently hydroxylated by these enzymes (37). We verified that our Tat-HIF/ODD/wt peptide is a substrate with similar affinity for the recombinant HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases as HIF/ODD/wt (Fig. 3A). We also show that intracellular delivery of Tat-HIF/ODD/wt (but not a control peptide with the proline hydroxylation sites mutated to alanine) stabilizes HIF-1α (Fig. 4), effectively activates HIF-dependent gene expression (Fig. 5), and protects embryonic rat cortical neurons from oxidative stress (Fig. 6). These findings suggest that Tat-HIF/ODD/wt is also an effective inhibitor of rat HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase. Future studies will determine which one or more of the described rat HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases needs to be inhibited in order to protect rat embryonic cortical neurons from oxidative stress.

What is the mechanism of neuroprotection by inhibitors of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases? These enzymes stabilize HIF leading to transcriptional up-regulation of a cassette of genes involved in hypoxic adaptation, including VEGF and erythropoietin (56, 58). The established ability of these peptide growth factors to prevent neuronal injury and death in vitro and in vivo makes them attractive candidates to mediate the neuroprotective effects of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibition. Additional studies are needed to determine whether HIF stabilization is necessary for the protective effects of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibition. Indeed, growing awareness of other substrates such as IRP2 (59) and RNA polymerase (60), whose stability can be regulated by the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases, suggests other plausible schemes in addition to or exclusive of HIF that may account for protection by HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibition. Even if HIF-1α stabilization is not necessary for the protection against oxidative stress or ischemia provided by low molecular weight or peptide inhibitors of the HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases, HIF-1α stabilization appears to be a good marker of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibition.

The ability of inhibitors of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases to prevent neuronal injury when given prior to permanent focal ischemia suggests that they be considered as neuroprotective agents in clinical situations where the imminent risk of ischemic or oxidative neuronal injury is high. Coronary bypass surgery, abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, and acute anterior wall myocardial infarction with a thrombus are examples of clinical situations where increasing the threshold for oxidative or hypoxic-ischemic brain injury is desirable. Studies are currently underway to define whether HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibitors are effective in preventing neuronal damage when given after the onset of ischemia or during the period of stroke recovery. The ability of HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibitors to induce expression of cellular, local, and systemic homeostatic responses to ischemia suggests that these agents may be useful in post-event treatment in addition to the preventative treatment described herein.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Freeman and Gregg Semenza for providing the HRE reporters. We thank Brett Langley, Philipp Lange, Kyungsun Suh, and JoAnn Gensert for their helpful discussions. We are especially thankful to Johanna Myllyharju for input and advice. We thank Yixin Ben for excellent technical assistance and Wayne Kleinman for excellent editorial assistance. We also acknowledge the support of the Spinal Cord Injury Research Board of the New York State Department of Health in this study.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS39170, NS40591, and NS46239 (to R. R. R.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The abbreviations used are: DFO, deferoxamine mesylate; 3,4-DHB 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate; hypoxia-inducible factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; HCA, homocysteate; DIV, day in vitro; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; AM, acetoxymethyl ester; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; RT, reverse transcription; MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion; TTC, 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride; DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; ANOVA, analysis of variance; FITC, fluorescein-isothiocyanate; HRE, hypoxia-response element; ICP-MS, inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

A. Siddiq and R. Ratan, unpublished observations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zecca L, Stroppolo A, Gatti A, Tampellini D, Toscani M, Gallorini M, Giaveri G, Arosio P, Santambrogio P, Fariello RG, Karatekin E, Kleinman MH, Turro N, Hornykiewicz O, Zucca FA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:9843–9848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403495101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kress GJ, Dineley KE, Reynolds IJ. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:5848–5855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05848.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connor JR, Menzies SL, Burdo JR, Boyer PJ. Pediatr. Neurol. 2001;25:118–129. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(01)00303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerlach M, Ben-Shachar D, Riederer P, Youdim MB. J. Neurochem. 1994;63:793–807. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63030793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson KJ, Shoham S, Connor JR. Brain Res. Bull. 2001;55:155–164. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castellani RJ, Siedlak SL, Perry G, Smith MA. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;100:111–114. doi: 10.1007/s004010050001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dexter DT, Wells FR, Lees AJ, Agid F, Agid Y, Jenner P, Marsden CD. J. Neurochem. 1989;52:1830–1836. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb07264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kienzl E, Jellinger K, Stachelberger H, Linert W. Life Sci. 1999;65:1973–1976. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00458-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sofic E, Riederer P, Heinsen H, Beckmann H, Reynolds GP, Hebenstreit G, Youdim MB. J. Neural Transm. 1988;74:199–205. doi: 10.1007/BF01244786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson CA. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2001;58:649–650. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/58.8.649a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith MA, Rottkamp CA, Nunomura A, Raina AK, Perry G. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1502:139–144. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazur-Kolecka B, Frackowiak J, Le Vine H, III, Haske T, Wisniewski HM. Brain Res. 1997;760:255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00327-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Good PF, Perl DP, Bierer LM, Schmeidler J. Ann. Neurol. 1992;31:286–292. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deibel MA, Ehmann WD, Markesbery WR. J. Neurol. Sci. 1996;143:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(96)00203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connor JR, Menzies SL, St Martin SM, Mufson EJ. J. Neurosci. Res. 1992;31:75–83. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490310111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schapira AH. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1410:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waldvogel D, van Gelderen P, Hallett M. Ann. Neurol. 1999;46:123–125. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199907)46:1<123::aid-ana19>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aisen P. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1994;356:31–40. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2554-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bralet J, Schreiber L, Bouvier C. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992;43:979–983. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90602-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipscomb DC, Gorman LG, Traystman RJ, Hurn PD. Stroke. 1998;29:487–493. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.2.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurn PD, Koehler RC, Blizzard KK, Traystman RJ. Stroke. 1995;26:688–694. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.4.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaur D, Andersen JK. Aging Cell. 2002;1:17–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2002.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowern N, Ramshaw IA, Clark IA, Doherty PC. J. Exp. Med. 1984;160:1532–1543. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.5.1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLachlan DR, Smith WL, Kruck TP. Ther. Drug Monit. 1993;15:602–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritchie CW, Bush AI, Mackinnon A, Macfarlane S, Mastwyk M, MacGregor L, Kiers L, Cherny R, Li QX, Tammer A, Carrington D, Mavros C, Volitakis I, Xilinas M, Ames D, Davis S, Beyreuther K, Tanzi RE, Masters CL. Arch. Neurol. 2003;60:1685–1691. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.12.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaur D, Yantiri F, Rajagopalan S, Kumar J, Mo JQ, Boonplueang R, Viswanath V, Jacobs R, Yang L, Beal MF, DiMonte D, Volitaskis I, Ellerby L, Cherny RA, Bush AI, Andersen JK. Neuron. 2003;37:899–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winterbourn CC. Toxicol. Lett. 1995;82:969–974. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaman K, Ryu H, Hall D, O'Donovan K, Lin KI, Miller MP, Marquis JC, Baraban JM, Semenza GL, Ratan RR. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:9821–9830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-09821.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willam C, Masson N, Tian YM, Mahmood SA, Wilson MI, Bicknell R, Eckardt KU, Maxwell PH, Ratcliffe PJ, Pugh CW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:10423–10428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162119399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ivan M, Kondo K, Yang H, Kim W, Valiando J, Ohh M, Salic A, Asara JM, Lane WS, Kaelin WG., Jr. Science. 2001;292:464–468. doi: 10.1126/science.1059817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Science. 2001;292:468–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu F, White SB, Zhao Q, Lee FS. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4136–4142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Semenza GL, Agani F, Feldser D, Iyer N, Kotch L, Laughner E, Yu A. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2000;475:123–130. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46825-5_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruick RK. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2614–2623. doi: 10.1101/gad.1145503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy TH, Schnaar RL, Coyle JT. FASEB J. 1990;4:1624–1633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosmann T. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirsila M, Koivunen P, Gunzler V, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30772–30780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Breuer W, Epsztejn S, Cabantchik ZI. FEBS Lett. 1996;382:304–308. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bettany AJ, Eisenstein RS, Munro HN. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:16531–16537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bederson JB, Pitts LH, Germano SM, Nishimura MC, Davis RL, Bartkowski HM. Stroke. 1986;17:1304–1308. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.6.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belayev L, Alonso OF, Busto R, Zhao W, Ginsberg MD. Stroke. 1996;27:1616–1623. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.9.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swanson RA, Morton MT, Tsao-Wu G, Savalos RA, Davidson C, Sharp FR. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:290–293. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ayoub IA, Lee EJ, Ogilvy CS, Beal MF, Maynard KI. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;259:21–24. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00881-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ratan RR, Ryu H, Lee J, Mwidau A, Neve RL. Methods Enzymol. 2002;352:183–190. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)52018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Majamaa K, Gunzler V, Hanauske-Abel HM, Myllyla R, Kivirikko KI. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:7819–7823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, O'Rourke J, Mole DR, Mukherji M, Metzen E, Wilson MI, Dhanda A, Tian YM, Masson N, Hamilton DL, Jaakkola P, Barstead R, Hodgkin J, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJ. Cell. 2001;107:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myllyharju J. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:15–24. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Metzen E, Berchner-Pfannschmidt U, Stengel P, Marxsen JH, Stolze I, Klinger M, Huang WQ, Wotzlaw C, Hellwig-Burgel T, Jelkmann W, Acker H, Fandrey J. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:1319–1326. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aarts M, Liu Y, Liu L, Besshoh S, Arundine M, Gurd JW, Wang YT, Salter MW, Tymianski M. Science. 2002;298:846–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1072873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang D, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Curr. Mol. Med. 2004;4:207–225. doi: 10.2174/1566524043479194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bergeron M, Gidday JM, Yu AY, Semenza GL, Ferriero DM, Sharp FR. Ann. Neurol. 2000;48:285–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis S, Helfaer MA, Traystman RJ, Hurn PD. Stroke. 1997;28:198–204. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prass K, Ruscher K, Karsch M, Isaev N, Megow D, Priller J, Scharff A, Dirnagl U, Meisel A. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:520–525. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang F, Sekine H, Kikuchi Y, Takasaki C, Miura C, Heiwa O, Shuin T, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Sogawa K. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;295:657–662. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00729-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Warnecke C, Griethe W, Weidemann A, Jurgensen JS, Willam C, Bachmann S, Ivashchenko Y, Wagner I, Frei U, Wiesener M, Eckardt KU. FASEB J. 2003;17:1186–1188. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1062fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang X, Zhu C, Gerwien JG, Schrattenholz A, Sandberg M, Leist M, Blomgren K. J. Neurochem. 2004;91:900–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.White KC. Pediatrics. 2005;115:315–320. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shi YH, Wang YX, Bingle L, Gong LH, Heng WJ, Li Y, Fang WG. J. Pathol. 2005;205:530–536. doi: 10.1002/path.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hanson ES, Rawlins ML, Leibold EA. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:40337–40342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302798200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuznetsova AV, Meller J, Schnell PO, Nash JA, Ignacak ML, Sanchez Y, Conaway JW, Conaway RC, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:2706–2711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436037100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]