Abstract

Sternoclavicular joint subluxation/dislocation injuries in the athlete are uncommon. They can be organised by degree (subluxation, dislocation), timing (acute, chronic, recurrent, congenital), direction (anterior, posterior), and cause (traumatic, atraumatic). The unusual case reported is an adolescent butterfly swimmer with recurrent bilateral sternoclavicular subluxation associated with pain and discomfort. The condition was treated and resolved with conservative management. The diagnosis, investigations, and treatment options are discussed.

Keywords: sternoclavicular joint injuries, subluxation/dislocation, shoulder injuries, athletic injuries, swimming injuries

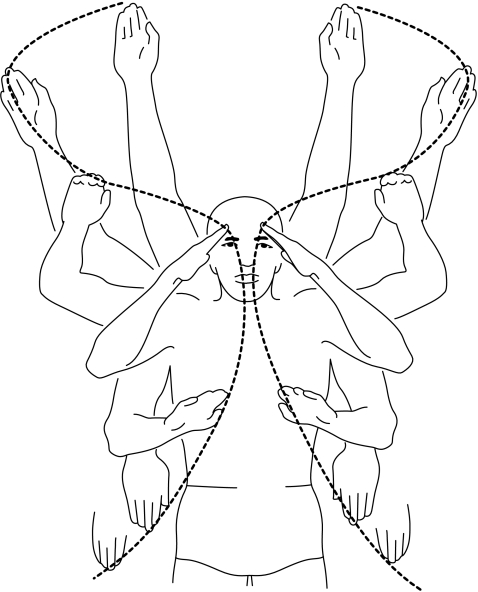

The shoulder girdle motion of the butterfly swimmer (fig 1) is dependent on smooth circumduction, centred at the glenohumeral joint and the sternoclavicular joint (SCJ). The SCJ is the only link between the shoulder girdle and the axial skeleton. The rotation and elevation of the clavicle occurs through the diarthrodial SCJ, with the clavicle acting as a strut. Clavicle movement allows the scapula to circumscribe a 40–60° arch around the SCJ. During the normal motion of the shoulder, the SCJ is also capable of 30–35° of elevation and 35° of flexion and extension.1

Figure 1 Shoulder girdle motion during the pull phases of a butterfly swimming stroke. Reprinted, with permission from Penguin, from Counsilman JE. Competitive swimming manual for athletes and coaches. 1978.

Atraumatic SCJ dislocation/subluxation is an uncommon athletic injury which occurs most often in adolescent female overhead athletes with multijoint laxity. On the basis of its bony anatomy, the SCJ is inherently unstable. However, the strong costoclavicular and intraclavicular ligaments, as well as capsular support, render the SCJ one of the least (1% of all joint dislocations, 3% of dislocations involving the upper extremity) dislocated joints in the body.2,3 SCJ injuries can be organised by degree (subluxation, dislocation), timing (acute, chronic, recurrent, congenital), direction (anterior, posterior), and cause (traumatic, atraumatic).4 Atraumatic SCJ subluxation/dislocation must be distinguished from traumatic injury, as the treatment strategies and outcomes are significantly different.4

Case report

A 14 year old female competitive high school swimmer presented for evaluation with a one year history of shoulder pain and a sensation of “popping” in the shoulder joints. The patient was a competitive butterfly specialist who initially experienced a left sided shoulder girdle discomfort associated with overhead movement. The reported complaint of shoulder girdle discomfort slowly progressed to a bilateral distribution over the period of a year. She was referred to her family orthopaedist, who performed clinical, plain film, and computed tomography (CT) examinations of both shoulder girdles. The patient was then referred to our office for a secondary orthopaedic evaluation of shoulder discomfort, and treatment recommendations. There was no recent or remote history of shoulder girdle dislocations, fractures, or other traumas. Patient and family history were unremarkable for congenital musculoskeletal/connective tissue abnormalities.

Physical examination revealed that the patient was neurovascularly intact, had symmetric shoulder girdle appearance without any visible abnormalities, and full shoulder range of motion bilaterally. Active and passive abduction with forward flexion provoked bilateral SCJ subluxation which was accompanied by an audible click. Her shoulder examination also revealed glenohumeral joint multidirectional instability, with hyperlaxity also present at wrist, elbow, and finger, knee, and ankle joints.

The primary diagnosis for this case was atraumatic bilateral subluxing SCJ, secondary to congenital multijoint hypermobility. Other diagnostic considerations to exclude would be ligamentous and bony abnormalities, including the growth plate, and degenerative or neoplastic lesions.

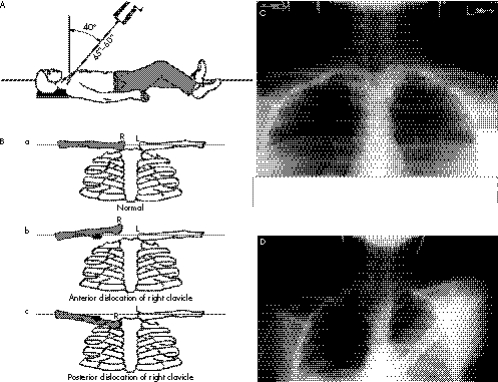

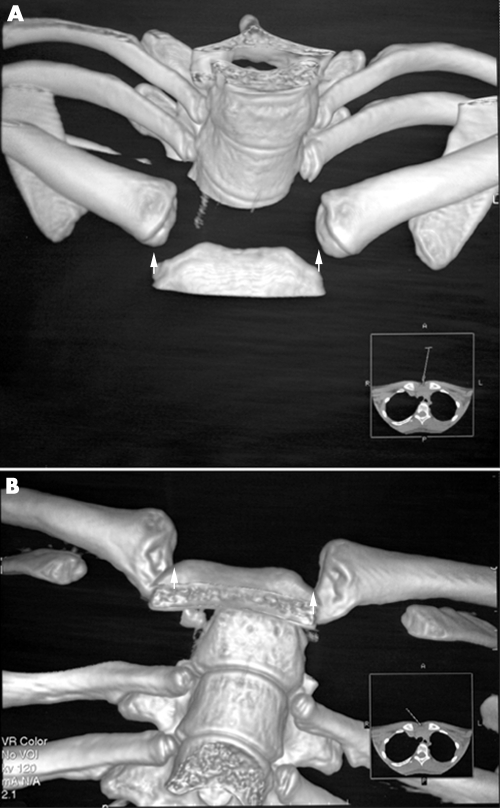

Plain film shoulder radiographs including true anterior to posterior (AP), lateral, Grashey, Y, and axial views were taken to rule out osseous shoulder pathology. These radiographs showed normal alignment with no abnormalities present. Special views ordered were serendipity (fig 2A–C) and stressed posterior to anterior (PA) (fig 2D). The serendipity and stressed PA view showed bilateral anterior subluxation of the SCJ. The three dimensional (3D) CT volume rendering reconstruction examination (fig 3A,B) of the SCJ also revealed a bilateral anterior subluxation of the SCJ, with no evidence of osseous injury.

Figure 2 (A) Technique for taking Rockwood's serendipity view. The view involves a 40° cephalic tilt radiograph showing both medial clavicles. (B) With the normal serendipity view, the sternoclavicular joints will project in the same line with one another (a). In anterior sternoclavicular dislocations, the injured side will project superior to the normal side (b). In posterior sternoclavicular dislocation, the injured side will project inferior to the normal side (c). (C) Serendipity view of patient demonstrating bilateral elevation (arrowheads) of the medial clavicles. (D) Stressed posterior to anterior view of patient's left shoulder showing elevation/ventral subluxation (arrowhead) of left sternoclavicular joint. (A) and (B) reprinted, with permission from Elsevier, from Garretson RB, Williams GR. Clinical evaluation of injuries to the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints. Clin Sports Med 2003;22:239–54.

Figure 3 (A) A three dimensional (3D) computed tomography (CT) volume rendering reconstruction anterior to posterior view of the patient's sternoclavicular joints, showing bilateral separation (arrowheads) of the medial heads of the clavicles from the manubrium. The normal appearance of this view would show the medial clavicular heads in close alignment and approximation with the manubrium. (B) A 3D CT volume rendering reconstruction cephalad view of the patient's sternoclavicular joints, showing bilateral clavicular (medial head) ventral subluxation (arrowheads) with respect to the manubrium. The normal appearance of this view would show the medial clavicular heads in close alignment and approximation with the manubrium.

A surgical intervention option involving resection of the medial SCJ, surgical stabilisation—for example, Fibrewire (Arthrex, Naples, Florida, USA)—or costoclavicular reconstruction was offered to the patient to allow her to return to her sport. The patient declined the surgical intervention, and decided to pursue other athletic activities that were less stressful to her shoulders—for example, running, cycling. A conservative course of formal and home physiotherapy was prescribed to stabilise and strengthen the shoulder girdle.

Discussion

This case is unique, as bilateral atraumatic SCJ subluxation is an uncommon finding in a competitive athlete. In the diagnosis and treatment of SCJ instability and pain in the adolescent athlete, osseous growth plate injuries, ligamentous injuries, congenital multijoint laxity—for example, Ehlers‐Danlos syndrome—and other lesions—for example, neoplastic—must be considered. Atraumatic SCJ posterior instability reported by Martin et al1 is rare, but is an important consideration because of the proximity of vital structures.

Atraumatic dislocations are usually seen in patients younger than 20 years, with a higher incidence in female than male patients. Medial epiphyseal injury is important to consider in a young patient with SCJ subluxation/dislocation. The medial SCJ epiphysis is the last to appear (18–20 months) and last to close (23–25 years) in the body.5 On physical examination, multiple joint laxity is often found in patients with SCJ subluxation/dislocation.6

Radiological evaluation of a recurrent atraumatic SCJ should include routine shoulder radiographs (true AP, lateral, Grashey, Y, and axial views) to rule out osseous shoulder pathology secondary to the abnormal SCJ movement. A stressed PA shoulder and serendipity SCJ views, as well as 3D CT volume rendering reconstruction images can provide definitive proof of this diagnosis and evidence of osseous injury. Magnetic resonance imaging can be used to visualise the SCJ soft tissue, including ligaments, joint capsule, and the fibrocartilagenous disc.

The uncommon nature of the injury and unfamiliar anatomy of this joint have kept treatment methods and results inconsistent. People who experience voluntary SCJ dislocation have shown a worse long term resolution of symptoms than those with either traumatic anterior or posterior dislocations.4 Complications of non‐operative treatment of SCJ injuries resulting from atraumatic subluxation/dislocation typically become asymptomatic over time. Most reported cases have been anterior, and complications of non‐operative treatment have been minimal, but may involve a visible prominence.7

Great care should be taken in considering any form of operative intervention for these patients. Although good operative results are attainable, they are unpredictable. Operative treatment of atraumatic SCJ injuries typically involves resection arthroplasty of the medial clavicle, with or without stabilisation of the first rib. Preservation or reconstruction of the costoclavicular ligaments is essential for joint stability and postoperative recovery.7 Rockwood and Odor8 reported on 37 patients (10–36 years old) with spontaneous SCJ dislocations and recurrent instability. Of these patients, 29 were treated conservatively. Twenty six patients still had intermittent subluxation episodes, but all 29 had no limitations on activities of daily living or athletic activities. Eight patients underwent an operative intervention, with resultant intermittent postoperative subluxation episodes (as in the non‐operative group), but these patients had considerable pain and limitation of daily activities.

What is already known on this topic

Atraumatic anterior subluxation/dislocation of the sternoclavicular joint is most common among adolescent athletes with multijoint laxity, and usually resolves over time without invasive intervention

Operative options are usually reserved for posterior dislocations, patients with non‐remittent pain, and those who have symptoms that affect their quality of life, as available operative interventions have produced inconsistent results

What this study adds

This case report shows the importance of appropriate clinical identification, radiological investigation, and a very conservative treatment approach toward an adolescent athlete with an atraumatic anterior subluxation/dislocation of the sternoclavicular joints

Current evidence indicates that there are significant operative risks and inconsistent benefits associated with SCJ stabilisation procedures. These risks include the proximity to vital organs, future migration of surgical stabilising devices, postoperative pain and scarring, iatrogenically induced decreased range of motion, and the recurrence of SCJ subluxation/dislocation. Operative repair is reserved for either posterior dislocation or non‐remittent symptoms that significantly affect either daily or athletic activities.

Congenital multijoint laxity often allows the athlete a greater joint range of motion and mechanical advantage than competitors with less mobile joints. Ligamentous hypermobility can also contribute to joint instability and repetitive motion injuries. The athletic patient with atraumatic SCJ subluxation should be informed that the symptoms of this disorder usually resolve over time, without the risks and uncertain outcomes of current operative intervention techniques.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Elaine N Skopelja MALS, Marlon V Lim RTR, Scott W Eathorne MD, David M Peck MD, Michael P Montico MD, William B Klein MD, Patrick W Comtois ATC, Alexia D Easterbrook MSLS AHIP, Carol Gilbert MSLS AHIP, Don DeCenzo LTA, and Robin Terebelo MLS, AHIP for their contributions to this publication.

Abbreviations

AP - anterior to posterior

CT - computed tomography

PA - posterior to anterior

SCJ - sternoclavicular joint

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Martin S D, Altchek D, Erlanger S. Atraumatic posterior dislocation of the sternoclavicular joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993292159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockwood C A, Matsen F A, Wirth M A. Disorders of the acromioclavicular joint. In: Rockwood CA, Matsen FA, Wirth MA, eds. The shoulder. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1998483–553.

- 3.Cave E F. Shoulder girdle injuries. In: Cave EF, ed. Fractures and other injuries. Chicago: Year Book Publishers, 1958258–259.

- 4.Bicos J, Nicholson G P. Treatment and results of sternoclavicular joint injuries. Clin Sports Med 200322359–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renfree K J, Wright T W. Anatomy and biomechanics of the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints. Clin Sports Med 200322219–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rockwood C A, Wirth M. Disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. In: Rockwood CA, Matsen FA, Wirth MA, eds. The shoulder. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1998555–610.

- 7.Lemos M J, Tolo E T. Complications of the treatment of the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint injuries, including instability. Clin Sports Med 200322371–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rockwood C A, Jr, Odor J M. Spontaneous atraumatic anterior subluxation of the sternoclavicular joint. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1989711280–1288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]