Abstract

Post-translational modifications of histones play a critical role in regulating genome structures and integrity. We have focused on the regulatory relationship between covalent modifications of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) and H3S10 during the cell cycle. Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that H3S10 phosphorylation in HeLa, A549, and HCT116 cells was high during prophase, prometaphase, and metaphase, whereas H3K9 monomethylation (H3K9me1) and dimethylation (H3K9me2), but not H3K9 trimethylation (H3K9me3), were significantly suppressed. When H3S10 phosphorylation started to diminish during anaphase, H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 signals reemerged. Western blot analyses confirmed that mitotic histones, extracted in an SDS-containing buffer, had little H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 signals but abundant H3K9me3 signals. However, when mitotic histones were extracted in the same buffer without SDS, the difference in H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 signals between interphase and mitotic cells disappeared. Removal of H3S10 phosphorylation by pretreatment with λ-phosphatase unmasked mitotic H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 signals detected by both fluorescence microscopy and Western blotting. Further, H3S10 phosphorylation completely blocked methylation of H3K9 but not demethylation of the same residue in vitro. Given that several conserved motifs consisting of a Lys residue immediately followed by a Ser residue are present in histone tails, our studies reveal a potential new mechanism by which phosphorylation not only regulates selective access of methylated lysines by cellular factors but also serves to preserve methylation patterns and epigenetic programs during cell division.

Histones are highly conserved proteins with a globular domain and a flexible amino-terminal tail. Covalent modifications of histone tails are essential biochemical processes that function to control the eukaryotic genomes. Extensive research in the past has demonstrated that reversible phosphorylation and methylation, as well as other post-translational modifications, play a critical role in regulating the dynamic condensation/relaxation of chromosomes that occur during DNA replication/repair, transcription, and cell cycle progression (1, 2).

Phosphorylation of histone H3 serine 10 (p-H3S10) is tightly associated with cell cycle progression; it also occurs when cells are exposed to certain environmental stresses or growth stimuli (3). Although p-H3S10 is minimal in interphase, it greatly increases during mitosis and meiosis (4, 5). Following the development of antibodies specific for p-H3S10, the precise temporal and spatial patterns of p-H3S10 have been clearly described in mammalian cells (6). p-H3S10 is initiated in late G2; it spreads throughout the chromatin and persists during prophase and metaphase as chromosomes undergo high orders of condensation. p-H3S10 rapidly diminishes during late anaphase and essentially disappears upon mitotic exit (6). The same cell cycle dependence of p-H3S10 was also demonstrated in plant and lower eukaryotic cells (7, 8). In mammalian cells, H3S10 is primarily phosphorylated by Aurora B during mitosis (9), whereas its phosphorylation is regulated by c-Jun amino-terminal kinase/mitogen-activated protein (JNK/MAP) kinases when the cells are exposed heavy metals such as nickel (10).

Many lysine residues in histone tails are methylated (2, 11). Recent studies have revealed that histone methylation is also a reversible process. Methylation of specific histone residues and the extent of methylation (mono-, di, and/or trimethylation) on the same residues are either critical for regulating gene expression or marks of heterochromatin and euchromatin in various organisms (2, 12, 13). It becomes increasingly clear that the methylation status of histones is essential for regulating transcription, gene expression, and cell cycle progression. Mitosis is a unique cell cycle phase in which duplicated chromosomes are highly condensed. This high order of chromatin compaction is particularly important for accurate chromosomal segregation and genomic stability maintenance during cell division. Because histones, primarily as scaffold proteins, function to facilitate the formation of high order structures of chromatin, we proposed that there existed cross-talk between histone methylation and phosphorylation during mitosis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture—HeLa and A549 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). HCT116 cells were kindly provided by Bert Vogelstein. Cells were cultured in culture dishes or on Lab-Tek II chamber slides (Fisher Scientific) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. HeLa cells were treated with nocodazole overnight. Mitotic cells were collected by shake-off.

Fluorescence Microscopy—Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min on ice before being permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 10 min. After fixation and permeabilization, cells were blocked in PBS2 containing 2.0% bovine serum albumin for 15 min. Primary antibodies and fluorescent dye-conjugated secondary antibodies were diluted into the same medium. Cells were incubated with antibodies to histone H3 mono-, di-, and/or trimethylated lysine 9 (H3K9me1, H3K9me1, or H3K9me3) (AbCam) and phosphohistone H3 (p-H3S10) (Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. Then cells were incubated with Alexa 488- (green) or Alexa 594- (red) conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) for an additional 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then co-stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1 mg/ml, Fluka), a DNA dye, for 5 min followed by washing three times with PBS. Images were collected using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal system.

Histone Extraction—Cells were lysed in either a Triton X-100-based extraction buffer (PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 (v/v)) or a RIPA containing SDS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) on ice for 10 min with gentle agitation. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. After removing the supernatant, the pellets were washed two times with a Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0, 10 mm). Pellets were collected after centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Washed pellets were resuspended in 0.4 n H2SO4 and incubated at 4 °C overnight. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min, the supernatants were collected. Extracted histones were then precipitated by the addition of acetone. The precipitated histones were resuspended in 4 m urea.

Immunoblotting—Approximately equal amounts of histones were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by electro-transferring fractionated samples to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The protein blots were probed with antibodies to H3K9me1, H3K9me, or H3K9me3. Specific signals were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit (or anti-mouse) secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology). Specific signals were detected using SuperSignal chemiluminescence reagents (Thermo Inc.). Equal amounts of histone loading were determined by Coomassie Blue staining.

Phosphatase Treatment—HeLa cells grown on chamber slides were fixed and incubated in a phosphatase buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mm NaCl, 2 mm EGTA, 0.01% (w/v) Brij-35) supplemented with or without λ-phosphatase (5 units/ml, New England Biolabs) for 1 h at 25 °C. At the end of incubation, cells were rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline and then incubated with antibodies for fluorescence microscopy. Protein blots were incubated in the same phosphatase buffer as above supplemented with or without λ-phosphatase (5 units/ml) for 1 h at 25 °C. After washing, the blots were probed for H3K9me2 signals.

In Vitro Histone Methylation Transfer Assay—One μg of biotin-conjugated histone H3 peptide or phospho(Ser-10)-histone H3 peptide (amino acids 1-21; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) was mixed with 0.15 μg of recombinant G9a (Upstate Biotechnology) and 1.1 μCi of S-adenosyl-l-[methyl-3H]methionine (13.3 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life Sciences) in a histone methylation transfer buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 9.0, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.5 mm dithiothreitol). The experiment was performed in triplicate. After incubation at 30 °C for 1 or 17 h, 10 μl of reaction mixture was spotted onto a P81 phosphocellulose filter (Upstate Biotechnology). The P81 filter was washed three times with 5 ml of ice-cold 0.2 m ammonium bicarbonate solution. The filter was then air-dried. The radioactivity retained on the filter was counted with a Wallac liquid scintillation counter model 1409 (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

In Vitro Demethylation Assay—Histones were extracted from both interphase and mitotic HeLa cells and dissolved in water. Recombinant FLAG-JHDM2A was expressed in insect Sf9 cells and purified by affinity chromatography using anti-FLAG resin (Sigma). For each in vitro demethylation assay, 3 μg of purified FLAG-JHDM2A protein was incubated with 5 μg of histones extracted from either mitotic or interphase HeLa cells, in a buffer containing 50 mm Hepes-KOH (pH 8.0), 100 μm FeSO4, 1 mm 2-oxoglutarate, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 2 mm ascorbic acid. After a 30-min incubation at 37 °C, EDTA, a chelator of divalent ions, was added to a final concentration of 1 mm to terminate the reactions. In a control reaction, EDTA was added to the reaction buffer before the addition of recombinant FLAG-JHDM2A protein. After the reaction, the H3K9 methylation and H3S10 phosphorylation status were detected by immunoblotting.

RESULTS

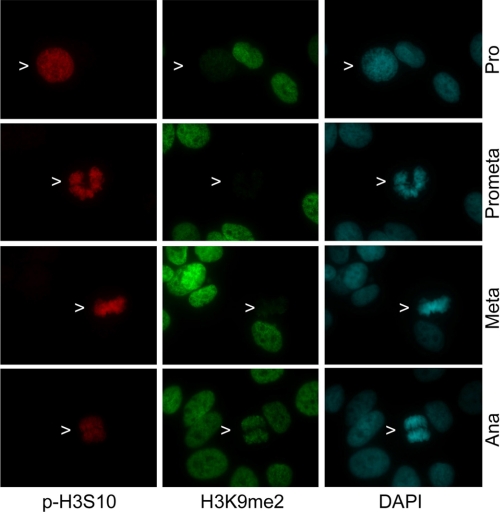

Given that H3K9 and H3S10 are well studied residues and that excellent antibodies are available for biochemical and cellular characterizations, we examined the status of H3K9 dimethylation as well as H3S10 phosphorylation in the same cells via fluorescence microscopy. Mitotic cells contained a high level of phosphorylated H3S10 (p-H3S10) (Fig. 1, arrows), whereas interphase cells had no detectable levels of the phosphorylation. In contrast, H3K9 dimethylation (H3K9me2) levels were uniformly high in interphase cells; these signals were either greatly diminished or disappeared in prophase, prometaphase, and metaphase cells (Fig. 1, arrows). Intriguingly, H3K9me2 levels reappeared when cells entered anaphase (Fig. 1, arrows).

FIGURE 1.

H3K9me2 was barely detectable in mitotic cells until anaphase. HeLa cells were stained with antibodies to phosphorylated serine 10 of histone H3 (p-H3S10) (red) and to dimethylated lysine of histone H3 (H3K9me2) (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Pro, Prometa, Meta, and Ana represent prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, and anaphase, respectively. Representative images are shown.

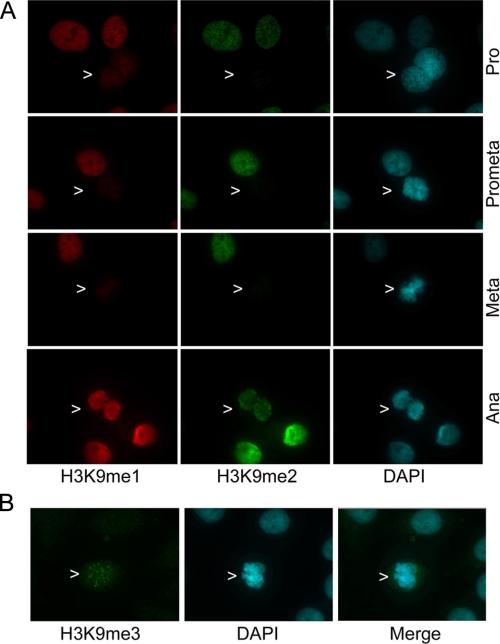

Because H3K9 mono- and dimethylation are catalyzed by the same lysine methyltransferase (13, 14), we examined the patterns of H3K9me1 in interphase and mitotic cells. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that when compared with those of interphase cells, H3K9me1 levels were also greatly diminished during prophase, prometaphase, and metaphase (Fig. 2A, arrows). On the other hand, H3K9me1 signals in anaphase cells reappeared, the levels of which were comparable with those in interphase cells (Fig. 2A, arrows). Thus, oscillation of H3K9me1 signals were parallel with those of H3K9me2, suggesting a similar underlying mechanism that affects the availability or detection of methylation signals. As control, we also analyzed H3K9me3 because this methylation, catalyzed by a different lysine methyltransferase, is regulated differentially during the cell cycle (15, 16). Although H3K9me3 signals were barely detectable in interphase cells, they increased in mitotic cells (Fig. 2B, arrows). However, different from those of H3K9me1 and H3K9me2, H3K9me3 signals exhibited a punctuated pattern (Fig. 2B), which is consistent with its known localization at heterochromatin (16).

FIGURE 2.

H3K9me1 signals were also low in early mitosis. A, HeLa cells were stained with antibodies to p-H3S10 (red) and to H3K9me2 (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Representative images are shown. B, HeLa cells were stained with an antibody to H3K9me3 (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Pro, Prometa, Meta, and Ana represent prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, and anaphase, respectively. Representative images are shown.

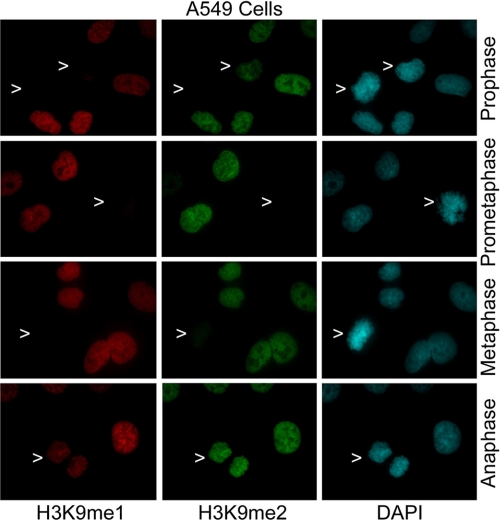

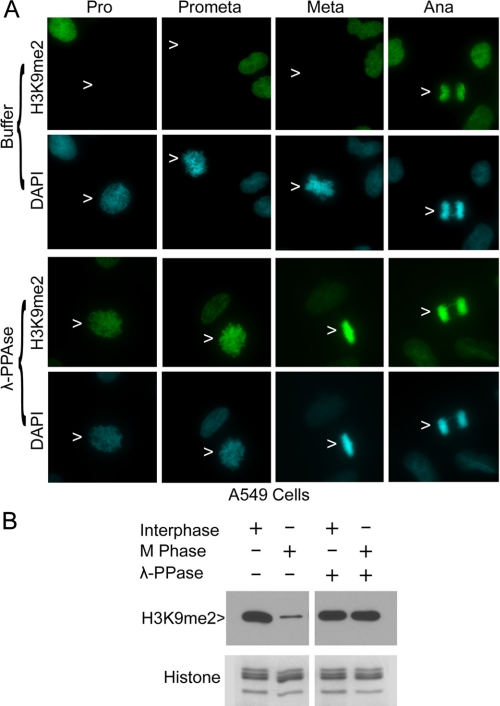

To eliminate a peculiar possibility that the absence of H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 signals in early mitotic cells was cell line-specific, we also examined H3K9me1 in A549 cells. We observed that H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 levels were significantly reduced in prophase, metaphase, and anaphase cells when compared with those of interphase cells (Fig. 3, arrows). Again, these signals reemerged when the cells entered anaphase (Fig. 3, arrows). Thus, our fluorescence microscopy reveals a common phenomenon that mono- and dimethylation of H3K9 is greatly suppressed in mitotic cells until anaphase.

FIGURE 3.

H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 signals were suppressed in mitotic A549 cells. A549 cells were stained with antibodies to H3K9me1 (green) and to H3K9me2 (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Representative images are shown.

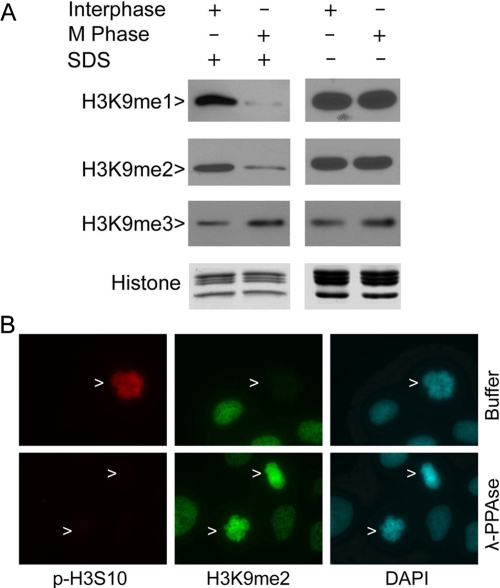

Next we analyzed the levels of H3K9 methylation using Western blotting. HeLa cells were treated with nocodazole, a microtubule-disrupting agent arresting cells at prometaphase. Mitotic cells were collected by shake-off. Collected mitotic cells, as well as interphase cells, were quickly lysed in a RIPA containing SDS. Immunoblotting analysis revealed that H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 levels were low in mitotic cells, whereas they were high in interphase cells (Fig. 4A). In contrast, H3K9me3 levels, low in interphase cells, were slightly increased in mitotic cells (Fig. 4A). Intriguingly, when histones were extracted with the RIPA containing no SDS, H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 signals, detected by immunoblotting, were high in mitotic cells. In fact, mitotic H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 signals were indistinguishable from interphase signals (Fig. 4A). In other words, the differences in H3K9 methylation between interphase and mitotic cells disappeared when a mild extraction buffer was used in the preparation of cell lysates.

FIGURE 4.

H3S10 phosphorylation blocks the accessibility of specific antibodies to H3K9. A, HeLa cells were treated with nocodazole overnight. Mitotic cells were collected via shake-off. Interphase cells were collected from HeLa cell culture after removing mitotic cells. Histones were extracted from interphase and mitotic cells with a RIPA supplemented with or without SDS. Approximately equal amounts of extracted histones were blotted for H3K9me1, H3K9me2, H3K9me3, and histones. B, HeLa cells were fixed and then treated with or without λ-phosphatase (λ-PPAse) before staining with antibodies to p-H3S10 (red) and to H3K9me2 (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Representative images are shown.

We suspected that an SDS-labile factor(s) might control the status of H3S10 phosphorylation, which in turn affected the recognition of methylation of H3K9. To test this possibility, HeLa cells grown on chamber slides were fixed and then treated with or without λ-phosphatase, which was capable of removing phosphate residues of many phospho-proteins. Upon treatment with λ-phosphatase, H3S10 was efficiently dephosphorylated when compared with that of controls (Fig. 4B, arrows). Surprisingly, dephosphorylation of H3S10 unmasked H3K9me2 signals in mitotic cells (Fig. 4B, arrows for prophase and metaphase cells). The phosphorylation-induced masking of methylation signals at H3K9 was not just limited to HeLa cells. Upon incubation with λ-phosphatase, strong H3K9me2 signals were detected in both A549 and HCT116 cells of various mitotic stages (Fig. 5A and supplemental Fig. 1). These results thus strongly suggest that H3S10 phosphorylation greatly interferes with the detection of methylation on the neighboring residue by fluorescence microscopy.

FIGURE 5.

Dephosphorylation of H3S10 unmasks H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 signals. A, A549 cells were fixed and then treated with or without λ-phosphatase (λ-PPAse) before staining with the antibody to H3K9me2 (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Pro, Prometa, Meta, and Ana represent prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, and anaphase, respectively. Representative cells of various mitotic stages are shown. B, histones were extracted from interphase and mitotic cells with a RIPA containing SDS. Duplicate blots treated briefly with λ-phosphatase or left untreated as control were blotted for H3K9me2 and histones.

To further confirm the possibility that H3S10 phosphorylation masked H3K9 methylation epitopes, interphase and mitotic histones extracted with the SDS-containing RIPA were fractionated on denaturing gels. Two identical blots with fractionated interphase and mitotic histones were incubated for 10 min in a PBS buffer supplemented with or without λ-phosphatase. The treated blots were then probed with the antibody to H3K9me2. As expected, mitotic histones contained greatly reduced H3K9me2 signals when compared with those of interphase histones; however, λ-phosphatase treatment uncovered H3K9me2 signals in mitotic histones (Fig. 5B), indicating that phosphorylation at the adjacent serine residue interfered with the binding or recognition of H3K9 methylation by the cognate antibody.

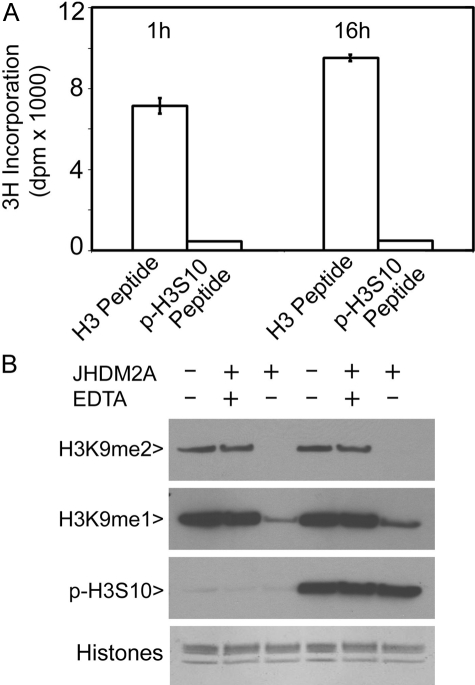

To test the possibility that H3S10 phosphorylation would block the access of cellular factor(s) to H3K9, we performed in vitro histone methylation assays. Biotin-conjugated histone H3 peptide or its Ser-10 phospho-counterpart was incubated in a reaction containing recombinant histone methyltransferase G9a, which is capable of targeting H3K9. Histone H3 peptide was rapidly methylated, detected as incorporation of radiolabeled methyl group into acid-insoluble peptide precipitates (Fig. 6A). On the other hand, Ser-10 phosphorylation completely blocked methylation of the peptide (Fig. 6A), indicating that phosphorylation of the serine residue greatly suppressed further modifications of the neighboring lysine residue.

FIGURE 6.

H3S10 phosphorylation selectively blocks the access of H3K9 modification enzymes in vitro. A, methylation of H3K9 by G9a was determined by an in vitro histone methyl transfer assay using either histone H3 peptide or phospho(Ser-10)-histone H3 peptide as substrate. Each bar represents the mean incorporation of radioactivity per 10 μl of sample ± standard deviation from three samples. B, histones extracted from interphase and mitotic cells were incubated with JHDM2A in a reaction buffer supplemented with or without EDTA. After the demethylation reaction, both treated histones, as well as the control ones, were blotted for H3K9me1, H3K9me2, p-H3S10, and histones.

We then asked whether H3S10 phosphorylation would have an effect on demethylation. Interphase and mitotic cell histones were incubated with or without JHDM2A, a Fe2+-dependent histone demethylase specific for H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 (17). As shown in Fig. 6B, JHDM2A efficiently demethylated both H3K9me1 and H3K9me2, and this demethylation was completely blocked by the addition of EDTA. Intriguingly, both interphase and mitotic histone H3 molecules were demethylated at a similar rate, although mitotic histone H3 was highly phosphorylated on Ser-10 (Fig. 6B). Given that all histone H3 molecules are phosphorylated during mitosis (18), our observations suggest that H3S10 phosphorylation may selectively blocks the access of cellular regulators to H3K9 in vivo.

DISCUSSION

In our study, we have revealed an unrecognized phenomenon in studying covalent modifications of histones. Phosphorylation of H3S10 is required for chromosomal condensation; it is also tightly associated with mitotic progression (6, 7). We have shown that this phosphorylation interferes with antibody recognition of H3K9me1 and H3K9me2, as well as with in vitro methylation of H3K9 peptide. H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 signals detected by cognate antibodies were lowest between early prophase and early anaphase when H3S10 phosphorylation and chromatin condensation is at the highest. When dephosphorylation of H3S10 occurs during anaphase, the signals of H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 reemerge (Figs. 1 and 2). At present, we do not know the exact molecular basis that explains failed recognition of H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 by specific antibodies when adjacent serine residue is phosphorylated. It could be due to stereo hindrance or masked antibody epitopes. Quantitative phosphorylation of H3S10 can add a bulky phosphate group affecting the conformation of neighbor amino acid residues. In addition, the high order of chromatin structures in mitotic cells can also affect the overall conformation of histone tails. It is conceivable that phosphorylation-dependent conformational changes in chromatin can prevent the binding of specific antibodies to H3K9me1 and H3K9me2. Alternatively, given the negative charge of the phosphate group, it is also possible that charge-charge interaction is substantially altered, resulting in inaccessibility of molecules recognizing H3K9me1 and H3K9me2. This appears to be an attractive possibility because the antibody epitopes of denatured proteins remain unmasked until removal of the phosphate residues (Fig. 5B).

The significance of our discovery is beyond technical considerations. It is highly possible that H3S10 phosphorylation is an important mechanism by which other covalent modifications of histone tails, including H3K9 methylation, are co-regulated during cell cycle progression. Specifically, cellular molecules (e.g. lysine methyltransferases), similar to those of the antibodies, are prevented from interacting with H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 in mitotic cells. Our in vitro histone methylation studies strongly support this notion (Fig. 6A). On the other hand, H3S10 phosphorylation does not prevent the access of JHDM2A because interphase and mitotic histone H3 molecules are demethylated at a similar rate by the enzyme (Fig. 6B). The latter observation suggests that H3K9 remains accessible by certain proteins in vivo, although its immediate downstream amino acid is phosphorylated during mitosis. It is also conceivable that new groups of molecules may become associated with H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 during mitosis or stress responses after H3S10 phosphorylation.

H3K9 mono- and dimethylation mediated by G9a plays an important role in regulating euchromatin. Given that gene expression is greatly influenced by chromatin structures, which in turn are controlled, to a large extent, by covalent modification of histones, it is conceivable that histone methylation patterns in euchromatin need to be tightly regulated. One attractive model is that H3S10 phosphorylation may serve to selectively prevent the methylation status (i.e. H3K9me1 or H3K9me2) from being further modulated during mitosis, therefore faithfully preserving gene expression patterns. It is imperative that two daughter cells inherit not only the same set of genetic information but also identical epigenetic programs during cell division.

Analysis of histone tails reveals additional adjacent lysine and serine structures. For example, H3K27, also an important epigenetic marker, is methylated, and its methylation is reversible (12, 19). Importantly, H3S28 is also phosphorylated during mitosis and meiosis (20). During meiosis, reversible acetylation and phosphorylation of histone H3 including serine 28 are key events in chromatin morphology and meiotic chromosome condensation (21). Besides histone H3, histone H2B contains a lysine residue (Lys-5) followed by serine residue (Ser-6). At present, it remains unknown whether Lys-5 is methylated and Ser-6 is phosphorylated and whether potential covalent modifications of these residues are regulated during the cell cycle. Given that H2B is phosphorylated in yeast (22) and that histone modifications are very conserved throughout eukaryotes, it is tempting to speculate that H2BK5 and H2BS6 may be regulated in a fashion similar to that of lysines and serines in histone H3 during cell division.

The past decade has witnessed a rapid increase in the study of reversible modifications of histones as a basic mechanism regulating their structures and functions. The identification of histone demethylases has ushered in a new era in the study of histone methylation as an important mechanism controlling chromatin remodeling, gene expression, and epigenetic regulation. As the result, numerous research papers have been published that study the level of H3K9 methylation and its regulation. Our current study, however, calls for a need to interpret with caution the results of some published studies, especially regarding the methylation level of H3K9 during the cell cycle.

Covalent modifications of histones are central to cell cycle progression and genomic stability. Ever increasing numbers and combinations of covalent modifications of histone tails can offer great diversity in epigenetically controlling the cell cycle, as well as development of organisms. Chromosome condensation and decondensation are a cyclic process during cell division. At the molecular level, histone tail modifications may represent transient, yet critical, marks modulating chromatin structures, thus allowing orderly progression of the cell cycle and faithful maintenance of genomic stability from generation to generation. Elucidation of the regulatory relationship between various types of histone modifications promises to reveal an additional layer of epigenetic mechanisms controlling the division of stem cells, somatic cells, and cancer cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank co-workers in the laboratory for helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA090658 (to W. D.) and ES005512 (to M. C.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains a supplemental figure.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; RIPA, radioimmune precipitation buffer.

References

- 1.Rice, K. L., Hormaeche, I., and Licht, J. D. (2007) Oncogene 26 6697-6714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shilatifard, A. (2006) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75 243-269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bode, A. M., and Dong, Z. (2005) Science's STKE 2005 re4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nowak, S. J., and Corces, V. G. (2004) Trends Genet. 20 214-220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prigent, C., and Dimitrov, S. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116 3677-3685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Hooser, A., Goodrich, D. W., Allis, C. D., Brinkley, B. R., and Mancini, M. A. (1998) J. Cell Sci. 111 3497-3506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei, Y., Yu, L., Bowen, J., Gorovsky, M. A., and Allis, C. D. (1999) Cell 97 99-109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaszas, E., and Cande, W. Z. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113 3217-3226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirota, T., Lipp, J. J., Toh, B. H., and Peters, J. M. (2005) Nature 438 1176-1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ke, Q., Li, Q., Ellen, T. P., Sun, H., and Costa, M. (2008) Carcinogenesis 29 1276-1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutherland, J. E., and Costa, M. (2003) Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 983 151-160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebert, A., Lein, S., Schotta, G., and Reuter, G. (2006) Chromosome Res. 14 377-392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tachibana, M., Nozaki, M., Takeda, N., and Shinkai, Y. (2007) EMBO J. 26 3346-3359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rice, J. C., Briggs, S. D., Ueberheide, B., Barber, C. M., Shabanowitz, J., Hunt, D. F., Shinkai, Y., and Allis, C. D. (2003) Mol. Cell 12 1591-1598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fodor, B. D., Kubicek, S., Yonezawa, M., O'Sullivan, R. J., Sengupta, R., Perez-Burgos, L., Opravil, S., Mechtler, K., Schotta, G., and Jenuwein, T. (2006) Genes Dev. 20 1557-1562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krouwels, I. M., Wiesmeijer, K., Abraham, T. E., Molenaar, C., Verwoerd, N. P., Tanke, H. J., and Dirks, R. W. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 170 537-549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamane, K., Toumazou, C., Tsukada, Y., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Tempst, P., Wong, J., and Zhang, Y. (2006) Cell 125 483-495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurley, L. R., D'Anna, J. A., Barham, S. S., Deaven, L. L., and Tobey, R. A. (1978) Eur. J. Biochem. 84 1-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swigut, T., and Wysocka, J. (2007) Cell 131 29-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houben, A., Demidov, D., Caperta, A. D., Karimi, R., Agueci, F., and Vlasenko, L. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1769 308-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bui, H. T., Van Thuan, N., Kishigami, S., Wakayama, S., Hikichi, T., Ohta, H., Mizutani, E., Yamaoka, E., Wakayama, T., and Miyano, T. (2007) Reproduction (Camb.) 133 371-382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu, J. Y., Sun, Z. W., Li, X., Reuben, M., Tatchell, K., Bishop, D. K., Grushcow, J. M., Brame, C. J., Caldwell, J. A., Hunt, D. F., Lin, R., Smith, M. M., and Allis, C. D. (2000) Cell 102 279-291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.