Introduction

Medicine, like scientific inquiry, is necessarily dynamic. As our understanding of health and disease continues to grow, medicine as we know it will change. Alternative therapies and perspectives that are coming to light will be illuminated by modern methods of inquiry applied to pre-modern healing systems. At the same time, patient demands and cultural concerns about health and healing influence the expansion of conventional medicine. The integrative medicine movement is a reflection of how these issues have tumbled together creating a medical field that is at once undefined and almost indescribable.

Integrative medicine is growing in popularity among consumers and healthcare providers alike. An August 7, 2006 article in the Los Angeles Times (1) asserted under the heading Twice as Strong that ‘Western medicine team[ed] up with acupuncture, yoga and herbs to fight both disease and pain …[is] going mainstream’. Three regional clinical programs were described. Each was based in a conventional medical clinic; each identified as an integrative or multidisciplinary practice.

Readers of the Twice as Strong article (Los Angles Times daily circulation is approximately 850 000 as of March 2006) (2) and viewers of The New Medicine television show broadcast March 29, 2006 (estimated audience between 4 and 9 million) (3, 4) learned that conventional biomedicine is undergoing a transformation from within. The popular message is that this movement is led by conventionally trained physicians who are opening their practices to include mind–body therapies as well as traditional techniques from other medical cultures such as acupuncture and oriental medicine (AOM). However, this is a narrow view. We hold a particular interest in the integration of AOM with conventional medicine where the breadth of this phenomenon can be readily comprehended.

This emergence of integrative medicine in the public eye is full of irony, giving rise to our question: what comprises integrative medicine exactly? It is not complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). (5) It is a phenomenon that has defined itself, with requirements for membership self-determined by each practitioner who chooses to promote her practice as integrative medicine.

Consider the following brief descriptions of integrative medicine providers.

A physician who completed a 300 h acupuncture course for physicians prefers to refer out for needling to licensed acupuncturists. He identifies as an integrative practitioner relying on his strong research skills and belief in nutrition as medicine. He has a full practice.

An acupuncturist teaches at many of the AOM colleges in Southern California. Born and trained in China she is widely recognized as an authority in orthopedic integrative medicine. She reads X-rays, tongue, pulse and inserts needles. She prescribes herbs. She treats side effects of chemotherapy. Her practice is full.

A conventional physician witnessed Chinese medicine on the mainland in the early 1980s. When he became ill upon return to the United States he found a Chinese practitioner of AOM after exhausting conventional medical solutions. He is now an herbal expert in demand as a speaker. He knows herbs will be the last medicine to enter the integrative medicine circle. He fights to include the most basic herbal formulas in his multi-discipline integrative clinic.

An American acupuncturist who became involved with Chinese medicine in the 1950s has been a witness to the history of AOM in the USA. He was among the first to earn an OMD degree (Oriental medicine doctorate), an early degree requiring ∼1000 h. The current master's degree requires nearly 3000 h. He believes physicians could learn enough about AOM in 1000 h, maybe less given their strong grounding in organ systems, basic anatomy and physiology. He believes traditional Chinese medicine and conventional Western medicine are very closely aligned; both allopathic with a central emphasis on the neurovascular system. He refers to his practice as One Medicine.

Integrative medicine is as much a prototypical grass-roots populist movement as it is a medical approach that has sprinted ahead of any simple, fixed and lasting definition. As a descriptive term integrative medicine is multi-functional and prone to metamorphosis. It is full of nuances that correspond to various factors including the background of the author(s) attempting to describe it. Integrative medicine is bound by context and orientation, not fixed by any set of criteria at any level. It is worthwhile to ask the question how will we understand exactly what is integrative medicine?

Malleable Definitions

Integrative medicine has gone through several generations of ‘definitional’ changes. The greatest change is from CAM to integrative. One of the major—and earliest (1999)—CAM textbooks was Essentials of CAM, edited by Wayne Jonas and Jeffery Levin (6). Although the title still reflected the model of CAM, the introduction of evidence-based medicine was prominent. One of the introductory chapters is ‘How to Practice Evidence-Based CAM.’ Two more recent textbooks, Integrative Medicine by Benjamin Kligler and Roberta Lee (7), and Integrative Medicine by David Rakel (8) both prefer the term integrative to CAM. The preface in Kligler asserts this new medicine is ‘renewing the soul of [conventional] medicine’. The foreword to Rakel, authored by Andrew Weil, draws a clear distinction between CAM and integrative medicine. Weil distinguishes CAM as modality-focused, especially regarding treatments not taught in conventional schools of medicine. He also distinguishes integrative medicine as evidence-based. Rakel's integrative approach puts a ‘holistic understanding of the patient’ at the center of the interaction (8). This emphasis on the patient continues in the Kligler and Lee textbook both in the forward, also written by Andrew Weil, and in the preface. These similarities are not surprising as all three authors trained with Andrew Weil.

The most important textbook written from a ‘CAM’ perspective is the Textbook of Natural Medicine edited by Pizzorno and Murray (9), both naturopathic physicians. They do not present the materials as an integrative medicine textbook even though many naturopaths consider themselves the prototype integrative physician. It is presented as a science-based textbook of natural medicine, in effect, an evidence-based practice model. Interestingly, the first chapter is ‘Eastern Origins of Integrative Medicine and Modern Applications’. The first edition was written in 1993 (currently in 3rd edition).

One of the earliest physician-edited textbooks on integrative medicine is the Micozzi series. The first edition was published in 1996 prior to Jonas. One can easily track the nuances driving definitional change with each new Micozzi text. The 2006 third edition of Fundamentals of Complementary and Integrative Medicine (10) was titled Fundamentals of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (italics added) in the first two editions. The prefaces in each edition illustrate the context-laden drivers for arriving at a suitable definition. In the brief half-page preface to the 1996 first edition, CAM is ‘a classic consumer movement and a current social phenomenon of significant dimensions.’ (11) CAM is also metaphysical as the reader is assured his views will expand regarding how ‘light, time, touch, sensation, energy and mind enter into health and medicine.’

In the 2001 second edition (12) CAM is almost anti-scientific. The much longer preface hints at particle physics and the reductionism of modern Western medicine as philosophically opposed to mind–body medicine and naturalistic views of human health. Energetics is tied to CAM and the brain is offered as a region for ‘remapping’ such that the mechanisms of action of energetics might be revealed. As in the first edition economics earn mention, e.g. the growth of alternative medicine is based upon what Americans ‘want and are willing to pay for’.

In the third edition CAM shares the limelight with integrative medicine. The movement has become a phenomenon supported by well-established data demonstrating popularity, support and growth.

Beyond Definitions

For the consumer and many providers the term CAM has already been supplanted by the term integrative medicine. Integrative medicine may hold more relevance for a widening range of providers that self-identify with the new medicine. For example, the American Medical Students Association's Humanistic Medicine Action Committee simply combines the two terms, publishing an ‘ICAM’ newsletter and hosting an online ‘ICAM’ resource center—Integrative, Complementary and Alternative Medicine (13).

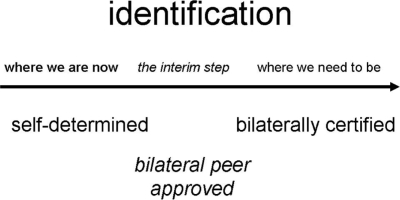

Defining the concept of integrative medicine is one first step towards understanding the phenomenon. However, a definition is more likely to emerge from key issues that are shaping the future of integrative medicine. These issues inevitably come to the fore when practice races ahead of regulation. They are clinical care, research, education standards, as well as economic opportunities. We allude to these topics here with intention to address them more substantially in subsequent reports. Identification among integrative medicine providers could progress from our current state of self-determination to bilateral peer approval and finally bilateral certification (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Identification among integrative medicine providers could progress from our current state of self-determination to bilateral peer approval and finally bilateral certification.

There is no unifying conceptual framework (14) of integrative medicine just as there are no unifying training standards or scope of practice. Attempts at one unifying definition are limited by context, often seeming speaker-dependent. In terms of collaborative medical practice in which the patient and doctor are partners, integrative medicine has been described as ‘a comprehensive, primary care system that emphasizes wellness and healing of the whole person (bio-psycho-socio-spiritual dimensions) as major goals, above and beyond suppression of a specific somatic disease.’ (15) From the perspective of scientific research, for example NCCAM (the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine under the National Institutes of Health), complementary and alternative medicine includes ‘healthcare practices outside the realm of conventional medicine, which are yet to be validated using scientific methods.’ (16) According to NCCAM, integrative medicine ‘combines mainstream medical therapies and CAM therapies for which there is some high-quality scientific evidence of safety and effectiveness.’ (17) A more transcendent view defines integrative medicine as ‘healing-oriented medicine that re-emphasizes the relationship between patient and physician, and integrates the best of complementary and alternative medicine with the best of conventional medicine.’ (18)

Practitioners outside conventional medicine often express concerns about ‘mainstreaming alternative medicine’ that will result in alternative practitioners being ‘relegated to a subservient position under Western medical doctors … being forced into a paraprofessional role leaving doctors with the final approval in a power-based model.’ (19) Additional concerns about assimilation include the dilution of CAM therapies and the loss of diversity within the field(s). However, many leaders believe that continuing movement towards integrative medicine will encourage transformation of ‘the entire system toward the values of holistic, person-centered care without losing access to the science and technology based cures of conventional medicine.’ (5)

The Bravewell Collaborative, a philanthropic organization which supports an impressive array of developments in integrative medicine, highlights the systemic challenges inherent to the movement by posing the question: ‘How can a highly formalized and large-scale system of institutions (conventional medicine) and a small-scale informal system of individual practitioners (CAM) integrate the best of both to form a better overall health care system?’ (5)

Bravewell anticipates two developmental spectra: ‘expansion of access to diverse CAM therapies’ and ‘transformation of the conventional healthcare system.’ Four possible outcomes to the development of integrative medicine are suggested: (i) high transformation of the conventional system with high expansion of CAM, wherein ‘conventional medicine is highly transformed by IM/CAM and CAM therapies are proven and accessible’; (ii) high transformation of the conventional system with low expansion of CAM, wherein ‘conventional institutions … expand their own ideas about prevention, public health, and patient education’ thereby starving ‘resources and attention from CAM so that its expansion is stalled’; (iii) low transformation of the conventional system with high expansion of CAM, wherein ‘conventional medicine … stays basically the same, [while] at the same time, CAM/IM research and outcomes-data further define the value of CAM …[and] IM and CAM institutions flourish’; and (iv) low transformation of the conventional system with low expansion of CAM, wherein the ‘conventional system does not change and the momentum for CAM/IM stalls.’ (5)

Who Practices Integrative Medicine?

No one really knows. As noted, most coverage, whether in popular media or scientific literature, is focused on conventional physicians who have integrated aspects of CAM into their medical practice or who serve as the head of an ‘integrated’ team of diverse practitioners from different disciplines. Ironically, this group is very likely the smaller cohort among a much larger group of providers who identify as integrative practitioners or who operate in self-identified integrative practices; including chiropractors, acupuncturists, naturopaths and other non-conventional providers.

The tendency to focus narrowly on conventional providers reflects a familiar cultural centrism consistent with the dominant position of conventional medicine within healthcare (20). Discussion of integrative medicine must acknowledge the extended group for many reasons, least of which is accurately estimating the total provider pool. We do not want to overlook another factor in more effectively defining integrative medicine; whether the integration is simply a matter of the provider having more modalities at his disposal or something greater for providers on both sides of the equation.

Who Certifies Integrative Medicine Practitioners?

For professional groups, identity and responsibility come with regulation. It is, therefore, crucial to consider the issue of certification in integrative medicine. The absence of a certification scheme means that provider identification process is self-determined. An operational definition of integrative medicine from the perspective of a regulatory agent might read as follows: integrative medicine is the practice of any medicine or medicines, determined by the practitioner, unbound by regulatory standards, with membership established by the individual.

It may be more practical to assert what is not integrative medicine. It is not conventional Western medicine, although many conventionally trained physicians promote their practices as integrative medicine. Indeed, NCCAM funds an impressive array of integrative medicine centers, all located at academic medical centers. Nobody actually knows how many conventional physicians identify as integrative to their patients and their colleagues, or more importantly for this discussion, what criteria they use to determine this designation.

Integrative medicine is not acupuncture and Oriental medicine, although many AOM practitioners promote their practices as integrative medicine, and practitioners of AOM are often included in integrative clinics. As with conventional physicians no one knows how many acupuncturists identify as integrative to their patients or colleagues. NCCAM, which defines AOM as an alternative whole medical system (21), has made a few educational awards to AOM colleges, most in partnership with conventional academic medical centers. The awards aim to strengthen traditional approaches to medical training within AOM colleges. This can be viewed as a clear step in the direction of trying to standardize integrative medicine training by supporting the adoption of conventional medicine training standards by at least a few AOM colleges. It is expected that graduates of these AOM colleges will be more likely to be employed in clinical settings affiliated with conventional medical systems and will enjoy privileged status when integrative medicine is finally regulated.

Definition, Scope of Practice, Standards and Regulation

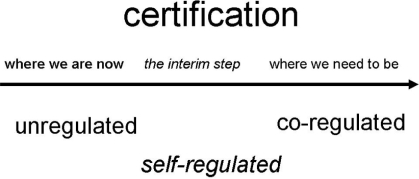

The definition of integrative medicine will become very important as scope of practice issues become more prominent. Defining integrative medicine has as much to do with regulating practice as with defining educational standards. In fact, one leads to the other. When a scope of practice is modified to include new diagnostics or therapeutics, training programs add content to the curriculum in the new areas of practice. This occurs routinely in conventional medical schools. The same should hold for AOM schools. If integrative medicine is necessarily bilateral (20), then standards should apply bilaterally. As things stand currently in the integrative healthcare arena, i.e. CAM and conventional disciplines, expectations for standards flow from the larger conventional disciplines to the CAM periphery where practice is less overtly regulated. It is axiomatic that exchange of knowledge, production of research and educational standards are currently not bilateral. Certification of integrative medicine providers might follow the developmental path from no regulation to self-regulation to co-regulation (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Certification of integrative medicine providers might follow the developmental path from no regulation to self-regulation to co-regulation.

We do not challenge the sincerity of the previous efforts to define integrative medicine. We have tried to show that the definition is malleable and, like CAM before it, depends on the perspective of the definer (22). The markers of definitional change have moved from observing the power of consumer economic choice, to spiritual regeneration of a mechanistic medicine, to the expansion of choice based on scientific evidence. In addition to a multitude of new treatment options, CAM offers conventional medicine a philosophy of holism (23), ‘new’ ways of looking at the complex phenomena of health and disease (24), and the concept of inherent healing capacity (vis medicatrix naturae), while conventional medicine offers CAM rigorous means to scientifically examine these practices and ideas (25). Integrative medicine, at its current stage of development, incorporates the best practices of CAM and conventional medicine into a unified treatment plan, a goal that requires both camps to step into the integrative circle and examine themselves and each other with an open mind. Integration of medical disciplines will first require movement from isolation to collaboration before real integration occurs (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Integration of medical disciplines could first require movement from isolation to collaboration before integration.

Regulatory Focus Will Turn to Education

We see integrative medicine as a moving target that will become more fixed and stable as sufficient pressures are brought to bear that demand descriptive clarification. Although clinical care is where the practical implications of integration first emerge, we strongly believe that research and education in integrative medicine will become focal points for the negotiation of the more rigorous definition. Given its long history of organized professional development and its clinical and economic dominance, it is likely that the standards of conventional medicine will provide the default criteria. How well-prepared are the fields that comprise complementary and alternative medicine, especially acupuncture and Oriental medicine, to undergo scrutiny? It is time to carefully examine this question.

References

- 1.Macgregor H. Twice as Strong. 2006. Los Angeles Times, August 7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Los Angeles Times Media Center – Circulation. [Retrieved May 7, 2007]; http://www.latimes.com/services/newspaper/mediacenter/la-mediacenter-circulation,0,7813109.story.

- 3.The Bravewell Collaborative – Transforming Healthcare. [Retrieved May 7, 2007]; http://www.bravewell.org/transforming_healthcare/public_education/

- 4.2006. The New Medicine viewing audience, University of Maryland Center for Integrative Medicine newsletter. Spring. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mapping the emergence of integrative medicine: a journey toward a new medicine (executive summary: short version) Clohesy Consulting. April 2003. Retrieved March 30, 2007 from: http://www.bravewell.org/transforming_healthcare/mapping_the_field/

- 6.Jonas WB, Levin JS. Essentials of Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kligler B, Lee R. Integrative Medicine: Principles for Practice. McGraw-Hill; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rakel D. Integrative Medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pizzorno JE, Murray MT. Textbook of Natural Medicine. 3rd. Churchill Livingston; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Micozzi MS. Fundamentals of Complementary and Integrative Medicine. 3rd. Saunders; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Micozzi MS. Fundamentals of Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 1st. Churchill Livingstone; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Micozzi MS. Fundamentals of Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2nd. Churchill Livingstone; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Medical Student Association – ICAM Resource Center. [Retrieved May 7, 2007]; http://www.amsa.org/ICAM/resources.cfm.

- 14.Hsiao AF, Hays RD, Ryan GW, Coulter ID, Andersen RM, Hardy ML, et al. A self-report measure of clinicians’ orientation toward integrative medicine. Health Serv Res. 2005;40((5 Pt 1)):1553–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell I, Pher C, Schwartz GE, Grant KL, Gaudet TW, Rychener D. Integrative medicine and systemic outcomes research. Arch Internal Med. 2002;162:133–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atsumi K, Kamohara S. Bridging conventional medicine and complementary and alternative medicine. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2005;24:30–4. doi: 10.1109/memb.2005.1411345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NCCAM – What is CAM. [Retrieved May 7, 2007]; http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/

- 18.Maizes V, Schneider C, Bell I, Weil A. Integrative medical education: development and implementation of a comprehensive curriculum at the University of Arizona. Acad Med. 2002;77:861–3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phelan KE. Integrative Medicine. 1998. Journey Editions. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stumpf S, Shapiro S. Bilateral integrative medicine, obviously. eCAM. 2006;3:46–50. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NCCAM – Whole Medical Systems. [Retrieved May 7, 2007]; http://nccam.nih.gov/health/backgrounds/wholemed.htm.

- 22.Cooper E. Complementary and alternative medicine, when rigorous, can be science (Editorial) eCAM. 2004;1:1–4. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghassemi J. Finding the evidence in CAM: a student's perspective. eCAM. 2005;2:395–7. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan S, Tillisch K, Mayer E. Functional somatic syndromes: emerging biomedical models and traditional Chinese medicine. eCAM. 2004;1:35–40. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiappelli F, Prolo P, Cajulis O. Evidence-based research in complementary and alternative medicine I: History (Lecture Series) eCAM. 2005;2:453–8. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]