Abstract

We summarize the results from a series of investigations of Japanese style acupuncture and moxibustion therapies on symptoms of the common cold that have been conducted (FTLE 1999–03, supported by the Foundation for Training and Licensure Examination in Anma- Massage- Acupressure, Acupuncture and Moxibustion). We also discuss the various interventions and concerns that we faced during these investigations. The subjects were students and teachers. The pilot study (FTLE1999) of a two arm (real and non-treatment control) RCT at a Japanese acupuncture school showed that manual acupuncture to a specific needling point at the throat clearly reduced symptoms of the common cold. The first multi-center (five centers) RCT (FTLE 2000) revealed a significant reduction in cold symptoms, by general linear model analysis (between groups, P = 0.024). To reduce the technical variation, we employed indirect moxibustion to the neck points as a uniform intervention in the next project (FTLE 2001) without statistically significant results. Then we elongated the periods of treatment from 2 to a maximum of 12 weeks (FTLE 2002) with different interventions accompanied by 4 weeks follow-up. The results were still not statistically significant. As the final project, we tried to develop a new experimental design for individualized intervention by conducting n-of-1 trials using elderly subjects in a health care center but without detecting a clear effect. In conclusion, the safety of Japanese acupuncture or moxibustion was sufficiently demonstrated; however, a series of clinical trials could not offer convincing evidence to recommend the use of Japanese style acupuncture or moxibustion for preventing the common cold. Further studies are required as the present trials had several limitations.

Keywords: multi-center RCTs, common cold symptoms, acupuncture, moxibustion, japanese style

Introduction

A frequently occurring minor illness, the common cold is a major cause of absence from work and school. Since the symptoms of the common cold are self-limited and usually recover spontaneously, the cold is not treated as a severe disease. However, medical costs for its treatment are relatively high (1,2) and a recent survey demonstrated that the cost in the US is estimated at 40 billion dollars per year (3), making the establishment of a standard procedure for its treatment an important concern. Although various procedures and therapeutic approaches for the common cold have been evaluated by rigorous clinical trials, there is still little concrete evidence for the establishment of a standard treatment (4–8).

Japanese acupuncture therapists have noticed that their patients have frequently commented that they did not catch a cold during the period that they were receiving acupuncture treatment for other disorders such as lower back and knee pain, etc. This is a very common occurrence for Japanese acupuncturists, suggesting that the prevention of the symptoms of common cold might be an indication for acupuncture.

Since the preventive and curative effects of acupuncture and moxibustion treatments have been well noted in Chinese traditional medicine (9–11), we planned to investigate these preventive benefits on the symptoms of the common cold. When we started to develop a protocol for the clinical trials in 1999, we discovered that there had been very few clinical trials on this aspect of acupuncture.

Here, we intend to introduce the activities of the EBM working group of the Research Department of the Japan Society of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (JSAM): The FTLE (The Foundation for Training and Licensure Examination in Anma- Massage- Acupressure, Acupuncture and Moxibustion) conducted a series of clinical trials during a 5-yr period from 1999 to 2003.

In 1999, this project started as a pilot study for acupuncture RCT with two arms (real and no-treatment control). Based on the results of the pilot study, a sample size was estimated and a multi-center manual acupuncture RCT was conducted in 2000. In 2001, indirect moxibustion was used instead of manual acupuncture to reduce technical difficulty and possible technical variations among the centers. In 2002, different interventions were employed in each center as a pilot study and the period of interventions were increased from 2 weeks (FTLE 2001) to 8–12 weeks. After conducting a series of RCTs, we employed a new experimental design, n-of-1 trials to evaluate individualized intervention. Certain results of these trials have been reported (12–15). Here we introduce our efforts in conducting acupuncture clinical trials and discuss several specific concerns peculiar to Japan.

Methods

Most participants were students and staff members of Japanese acupuncture schools, colleges and universities. Subjects who were infected with the influenza virus were excluded. The subjects, who gave a written informed consent, were allocated randomly to the real intervention group and no-treatment control group by a computer program operated by an independent controller of EBM working group of JSAM (Japan Society of Acupuncture and Moxibustion). The protocols of these investigations were approved by a local ethics committee of Meiji University of Oriental Medicine.

In FTLE 1999, a pilot study of acupuncture on common cold symptoms was conducted as the first project at an acupuncture school (one center included). A total of 24 subjects were registered then randomly allocated to the acupuncture group (n = 12: 8 males, 4 females, mean age: 27.2) or control group (n = 12: 8 males, 4 females, mean age: 27.5). One subject in the acupuncture group dropped out due to serious illness. There was no statistically significant difference between the age and male/female ratios of the acupuncture and control groups (χ2 test, P > 0.05). In FTLE 2000, a multi center RCT of acupuncture on common cold symptoms was conducted in four acupuncture schools and one acupuncture university (five centers included). A total of 326 subjects were registered then allocated to the acupuncture group (n = 163, 99 males; 64 females) or control group (n = 163, 101 males; 62 females). There was no significant difference between the groups regarding age and sex. In FTLE 2001, a multi-center RCT of indirect moxibustion on common cold symptoms was conducted in five centers. A total of 367 subjects were registered then randomly allocated in each center. Indirect moxibustion group (n = 183, average age of 29.3 + 8.9, 116 males, 67 females; three dropouts), control group (n = 184, average ages of 29.9 + 8.9, 113 males, 71 females; two dropouts). There was no significant difference between the groups regarding age and sex (χ2 test, P > 0.05). In FTLE 2002, four centers participated. A total of 232 subjects were randomly allocated to experimental and waiting list control groups in each center. Two centers used the same indirect moxibustion and one center used direct moxibustion and the other center used a circular skin acupuncture needle instead of indirect moxibustion. In FTLE 2003, a single subject experimental design (n-of-1 trial) was conducted in a nursing center. Two elderly females participated in this program and the indirect moxibustion was used. The results were analyzed by Randomization test (R test).

Interventions

Manual Acupuncture

Acupuncture needles of sterilized single usage type (140–160 μm) in diameter, Seirin Co. Ltd, Japan) were used. A specific needling point for throat pain relief founded by Japanese acupuncturist Yoneyama (called Y point) was used. The points located about 1.5 cm (the width of finger) lateral to the midline. The acupuncture needle was gently inserted then manipulated (sparrow pecking technique) for inducing ‘de-qi’ sensations which project deep into the throat and continued for 15 s bilaterally. Acupuncture treatments were performed twice a week for 2 weeks (a total of 4 times) and a 2 week follow-up period was scheduled (FTLE1999, 2000).

Press Tack Acupuncture Needle

The needles used in FTLE 2001 have a fine pin press type surface, are 0.9 mm in needle length with a ring handle of 2.8 mm diameter with 10 × 10 mm adhesive tape, sterilized and individually packaged (Pyonex, Seirin Co. Ltd). These were used at one center as safe and easily applicable unique Japanese style acupuncture and are usually employed as a sham intervention.

Moxibustion (Indirect Moxibustion)

Indirect moxibustion (Sen-nen Kyu, Co. Ltd Japan) was used. The moxa was rolled to a column with a diameter of 5 mm with thin paper and fixed on a thick circular sheet (4 mm in thickness, 14 mm in diameter) with a small hole of 3 mm at the center. The basement of the sheet was covered with adhesive tape so that it was easy to attach to the skin surface. In several cases, the temperature of the skin beneath the indirect moxibustion after the ignition was monitored by a thermo-couple with a time constant of 0.1s, (IT-18, DAT-12, Physitemp Instrument Inc.). It increased gradually and reached its peak temperature of 49.6 ± 2.3°C (mean ± SD) about 3 min after the onset of stimulus (16).

Indirect moxibustion was done at least three times in a week for 2 weeks (at least 6 treatments) in FTLE2000 project. In FTLE 2001 protocol, the treatment periods were elongated from 2 weeks to 8–12 weeks and 4 week follow- up periods were scheduled. Indirect moxibustion was applied to the acupuncture points of Daitsui (GV 14) and bilateral Fu-chi (BL 12). In FTLE 2001, other acupuncture points were added dependent on the symptoms of the subjects.

Direct Moxibustion

In FTLE 2002, one center used direct moxibustion for the symptoms of the common cold as a pilot study. A small cone of moxa (half size of rice grain) was made manually and put on the skin directly then burnt until the subject felt pain and removed immediately and repeated three times at each acupuncture point. Bilateral Tsu-Sanli (ST 36) points were used.

Outcome Measures

Common Cold Diary and Common Cold Questionnaire

The daily condition of the subject was recorded on the common cold diary (CCD) and common cold questionnaire (CCQ). The former was simple, recorded in a binary form (yes or no). The latter was a questionnaire consisting of 15 categorical items with 4–5 levels. To test the reliability of the questionnaire, the same questionnaire was completed twice at 90 min intervals on the final recording day.

Subtype Measurement of Lymphocytes

Blood samples were collected three times (before acupuncture intervention, immediately after the fourth final acupuncture treatment and one week after the last treatment). Those cells with the surface markers of CD2+, CD4+, CD8+, CDl4+, CD19+ and CD56+ and IL-4, IFN-α, IL-1β positive cells stained with monoclonal antibodies were analyzed by flow cytometry (17).

Reporting adverse events

The subjects were asked to report every kind of adverse event they experienced on the CCD and CCQ questionnaire. The date of recording did not restrict on the day of acupuncture treatment.

Data analysis

CCD (yes/no) data of both groups were analyzed by Kaplan–Meier's survival analysis and then Cox regression analysis was performed to analyze the data in detail. The analysis by the general linear model (GLM) of repeated measures was also used (18,19) instead of the conventional repeated measure of ANOVA, because it was not applicable for the existence of several missing data. SPSS 7.5 for Windows and Medical Pack (SPSS Inc.) were used for data analysis. Randomization test was used for the analysis of the data obtained by n-of-1 trial (Free program running in Microsoft Excel macro program).

Results

FTLE1999

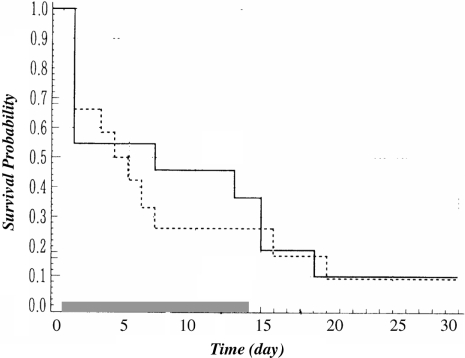

The initial scores of common cold incidence of the two groups were almost the same. Figure 1 shows the results of Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of CCD. The survival probability curves clearly demonstrate that the acupuncture group (solid line) showed higher survivals (who did not catch cold) than that of the control group in the initial 2 weeks and then fell to the same level with the control. The results also demonstrated that the onset of cold systems was delayed for about 2 days in the acupuncture group compared with the control. These results indicate that acupuncture treatment produced a preventive effect on the appearance of common cold symptoms. The total number of days that the subjects had common cold symptoms in the acupuncture group was lower than that of the control group, showing that acupuncture stimulation was curative as well. The FTLE 1999 was conducted as a pilot study and we could confirm that acupuncture had a positive influence on symptoms of the common cold using CCD and CCQ. We used the data for sample size calculation for the next multi-center trials and did not analyze the data in more detail because of the small number of the subjects.

Figure 1.

Survival curves in Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (FTLE 1999).The subjects who entered ‘yes’ in the CCD were deleted from the survivals. Acupuncture group: solid line, no treatment control group: dotted line. A vertical solid bar indicates the period of intervention.

FTLE2000

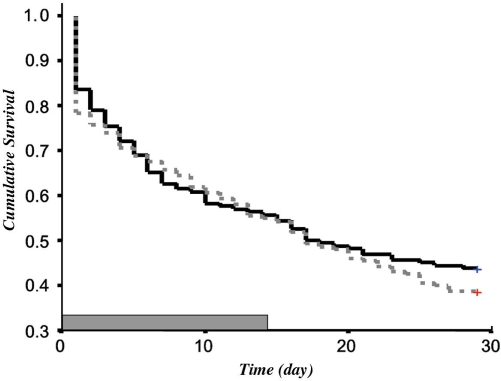

Initial incidences of the subjects with CCD yes and no (survivals) of the acupuncture and control groups were 28 and 36, respectively. During the experimental period, the survivals of the acupuncture group reduced more rapidly than those of the control but this reversed at the end of the trial. The results of Cox regression analysis are shown in Fig. 2. No statistically significant positive effect on the prevention of common cold symptoms was found in the acupuncture group. However, significant positive results in reducing CCD scores (curative effect) were observed in two centers (B, C).

Figure 2.

Survival curves for the Cox regression analysis (FTLE 2000). The subjects who entered ‘yes’ in the CCD were deleted from the survivals. Acupuncture group: solid line, no treatment control group: dotted line. A vertical solid bar indicates the period of intervention.

The incidence of CCD for 28 days (during acupuncture period and follow-up) was analyzed by repeated measures of GLM. Although no significant difference of CCD counts between the acupuncture and control groups was found (P = 0.325), a highly significant positive effect of acupuncture was detected in center B (P < 0.001). Significant inter-center (P = 0.003) and sex differences (P = 0.027) were also detected in GLM analysis.

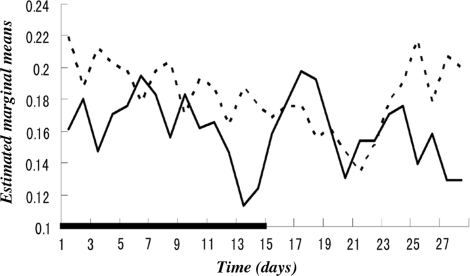

Figure 3 shows the time courses of estimated marginal means (EMMs) of item 14 of CCQ (degree of the common cold) in two groups during 28 days. In the acupuncture group (solid line), the EMM values tended to decrease during the acupuncture stimulation period (thick horizontal bar), then it reduces remarkably at the end of acupuncture stimulation. On the other hand, those of the control (dotted line) gradually decreased with fluctuation for 20 days then rapid increase. The results of analysis by GLM using CCQ data are as follows. There was a significant positive effect on the symptoms of the common cold in the acupuncture group (P = 0.024, group comparison). However, it should be noted that a significant negative result (P = 0.035) was also detected in center A. Based on the CCQ data, a significant sex difference (P = 0.005) was also detected. We must be cautious when forming conclusions about the influence of acupuncture.

Figure 3.

Acupuncture on CCQ scores during the trial (FTLE 2000).The estimated marginal means (EMM) of the item 14 ‘degree of common cold’ in acupuncture (solid line) and control (dotted line) groups are shown. The higher value indicates the worse symptom. In the acupuncture group, marked decrease of estimated marginal means (EMM) was observed at the end of treatment (14 days).

Thirty two healthy volunteers (aged 22 to 39, mean age of 27) in one center participated in the analysis of lymphocytes. Table 1 summarizes the results of manual acupuncture on the CD2+, CD4+, CD8+, CD14+, CDl9+ and CD56+ positive cell counts and IL-1β, IL-4 and IFN-γ containing cell counts. Although there was apparent change in cell counts of several subtypes among the time series data, no statistically significant difference was detected between the acupuncture vs control group in the subtypes measured. The subgroup analysis of CCQ in the subjects of the center showed no significant difference between the acupuncture treatment and control groups.

Table 1.

Results of analysis of lymphocytes subpopulation and cytokine containing cells in acupuncture and control groups

| Acupuncture | Control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| before | during | after | before | during | after | |

| CD2 | 47.01 ± 10.48 | 32.47 ± 8.70 | 24.45 ± 9.60 | 51.89 ± 1039 | 34.57 ± 10.36 | 25.99 ± 8.47 |

| CD4 | 28.56 ± 5.56 | 25.55 ± 6.45 | 22.00 ± 5.92 | 31.98 ± 5.80 | 26.07 ± 8.46 | 25.29 ± 4.52 |

| CD8 | 22.41 ± 7.78 | 23.49 ± 7.67 | 18.90 ± 5.52 | 24.50 ± 5.98 | 22.74 ± 7.04 | 20.88 ± 4.95 |

| CD14 | 46.97 ± 10.94 | 62.71 ± 8.55 | 34.28 ± 9.26 | 48.10 ± 11.05 | 63.62 ± 8.14 | 33.00 ± 10.78 |

| CD19 | 15.50 ± 7.31 | 14.12 ± 5.78 | 14.82 ± 6.22 | 12.83 ± 4.06 | 11.95 ± 3.61 | 11.26 ± 2.43 |

| CD56 | 17.23 ± 3.99 | 16.29 ± 4.30 | 18.98 ± 9.83 | 19.86 ± 6.67 | 17.51 ± 6.37 | 20.88 ± 8.26 |

| IL-4 | 1.58 ± 0.90 | 1.15 ± 0.62 | 1.72 ± 0.52 | 1.80 ± 1.10 | 1.60 ± 0.76 | 2.02 ± 2.63 |

| IFN-γ | 1.94 ± 0.92 | 13.01 ± 10.21 | 19.40 ± 12.12 | 2.83 ± 2.55 | 17.87 ± 9.44 | 17.04 ± 9.75 |

| IL-1β | 6.24 ± 3.50 | 8.82 ± 5.00 | 11.92 ± 3.85 | 6.46 ± 4.20 | 8.63 ± 2.77 | 11.01 ± 2.55 |

FTLE2001 (Multi-Center Indirect Moxibustion)

The total score of CCQ (items 1–13) was calculated and the subjects assumed to have the common cold + (dropout from the survivals) when the score reached 10. The initial survivals of the moxibustion and control groups were 162 (21 excluded by cold symptoms) and 169 (15 excluded by cold symptoms), respectively. The total number of survivals in the moxibustion group tended to be higher than the control during the experimental periods of 42 days and the final survivals of the moxibustion and control groups were 70 and 49, respectively. Cox regression analysis demonstrated some preventive effects of indirect moxibustion in three centers but without statistical significance (P = 0.066, 0.007, 0.066).

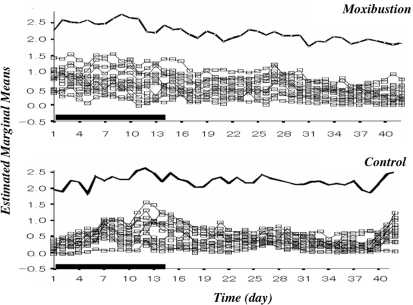

Figure 4 shows the estimated marginal means (EMMs) of all 15 items of CCQ during the experimental periods. The upper traces are those of acupuncture and the lower ones were those of control groups. The higher scores indicate much more severe symptoms. It is clear that the baseline EMMs in all items of the moxibustion were higher than the control. In the moxibustion group, the EMM values in general tended to decrease during the moxibustion periods (white columns) and after the cessation of the intervention. On the contrary, the EMM values clearly increased during the intervention periods and at the end of the experiments (42 days) in the control group. The thick lines, indicating general condition (item 15), also indicate the similar tendencies in each group.

Figure 4.

Indirect moxibustion on the EMM of CCQ scores (FTLE 2001). The estimated marginal means (EMM) of the 15 items in acupuncture group (upper traces) and the control group (lower traces) are shown. The higher value indicates the worse symptoms. In the acupuncture group, initial high scores of EMM tended to decrease and the scores continued until the end of trial.

GLM analysis of indirect moxibustion demonstrated a significant difference according to sex: (P = 0.047), however, no significant difference between the groups (acupuncture vs control) and centers (P = 0.135) was detected (P = 0.225). The latter result suggests indirect moxibustion reduced the inter-center difference compared with that of acupuncture needling to the throat in FTLE 2000.

There was a highly significant correlation between total CCQ score (1–13) and item 14 (r = 0.834, P < 0.001), indicating that the item 14 in CCQ reflected various symptom changes of common cold.

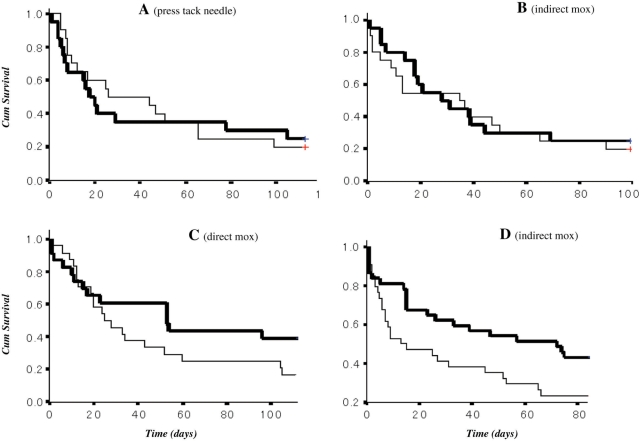

FTLE2002 (Long-Term Intervention: Four Pilot Studies)

Four pilot studies with long intervention periods (8–12 weeks) and 4 week follow-ups were conducted. A total of 232 subjects were registered and allocated to the intervention and no-treatment control groups randomly in each center. In each center, the initial survival rates of both groups were almost the same and no statistical significance was detected (χ2 test, P > 0.05).

Figure 5 demonstrates the Kaplan–Meier survival curves obtained in each center. Thick lines are intervention groups and thin lines are control groups. The survival curves varied with each center. In A center, 46 subjects were randomly allocated to the circular skin needle group (12 weeks, n = 23) and the non-treatment control group (n = 23). The mean days of survival of skin acupuncture and control groups were 45 (95% CI: 25–65) and 47 (95% CI: 29–65), respectively. The Log rank test indicated no difference between the groups (P = 0.90).

Figure 5.

The influence of various interventions on the survival curves (FTLE 2002). Thick lines indicate the group of active intervention and thin lines indicate the group of no treatment group.

In B center, 42 subjects were randomly allocated to the indirect moxibustion group (10 weeks, n = 21) and non-treatment control group (n = 21). The mean days of survival of indirect moxibustion and control groups were 45 (95% CI: 27–58) and 41 (95% CI: 25–57), respectively. The survival periods were almost the same and no difference between the groups was detected (Log rank test, P = 0.75).

In C center, 72 subjects were randomly allocated to the direct moxibustion group (three moxa cones, twice a week, 12 weeks, n = 35) and non-treatment control group (n = 37). The mean days of survival of moxibustion and control groups were 61 (95% CI: 42–80) and 45 (95% CI: 29–61). A slightly longer survival period was observed, but there was no statistically significant difference between the groups (Log rank test, P = 0.15).

In D center, 72 subjects were randomly allocated to the indirect moxibustion group (three times a week, Daitsui (GV 14), n = 37) and non-treatment control group (n = 35). The mean days of survival of indirect moxibustion and control groups were 51 (95% CI: 40–62) and 34 (95% CI: 22–45), respectively. A statistically significant difference between the groups was detected by the Log rank test (P = 0.042), however further statistical analysis using Cox regression analysis resulted in no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.138) and demonstrated a significant difference between the sexes.

The present long-term intervention studies were conducted as pilot studies to search for adequate interventions to prevent common cold symptoms. The overall results we obtained, however, were negative.

FTLE2003 (n-of-1 trials)

The experimental (indirect moxibustion + conventional treatment) and control (conventional treatment only) periods were allocated in random order (8 weeks of treatment periods and 8 weeks of control periods). During the treatment periods, subjects were treated with indirect moxibustion to Dai-tsui (GV 14) and bilateral Fu-chi (BL 12) 3 times a week. In each point, three moxa-cones were burnt repetitively. The common cold questionnaire (CCQ) was used to evaluate common cold symptoms.

Concerning the presence of common cold symptoms, there were no significant differences between the treatment and control periods. Moreover, concerning common cold symptoms, there were no significant differences of CCQ scores between treatment and control periods. Indirect moxibustion did not influence the common cold symptoms in these randomly allocated n-of-1 trials.

Reliability Test of the CCQ (FTLE 2000)

A reliability test was done on the final day of acupuncture treatment. Cronbach's α value of the repeated CCQ measurement was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.90, 0.94) and the reliability test using ICC (intra-class correlation coefficient) was 0.998. These results clearly show that the CCQ we used was sufficiently reliable for evaluating symptoms of common cold.

It should be noted, however, the validity test for CCQ of objective parameters related to common cold symptoms was not conducted, so the CCQ data should be interpreted carefully.

Incidence of Adverse Events

In FTLE 2000, a total of 1280 acupuncture needle penetrations were made in this RCT and 10 minor adverse events were reported. These included subcutaneous bleeding (four cases), paresthesia in the throat (five cases), and flutter (one case). The incidence rate was 0.8%. No severe adverse events were reported in acupuncture stimulation to the throat (Y point).

Regarding indirect moxibustion in FTLE 2001, no severe adverse event was reported. Minor wheals infrequently developed and cream helped to heal these without scarring. Regarding the press type circular skin needle, no severe adverse events were reported. Direct moxibustion was used in one center in FTLE 2002 without severe adverse event.

Discussion

Significant therapeutic benefits on common cold symptoms were detected in the pilot study and the first multi-center RCT of manual acupuncture. After this, we performed a series of multi-center RCTs. Acupuncture manipulation to the throat induced a statistically significant positive result in the first RCT. To strengthen the evidence of Japanese style acupuncture and moxibustion, we modified the procedures to include indirect moxibustion, surface acupuncture and direct moxibustion instead of manual acupuncture and lengthened the duration of treatment (2 to 12 weeks of intervention). However, these changes in procedure and duration of intervention did not lead to greater benefits. Several concerns associated with these projects will be summarized and discussed.

Studies FTLE1999 and 2000 demonstrated that manual acupuncture to the Y points at the throat reduced the incidence of the common cold. Y points had long been used to relieve sore throats at the acupuncture school where the study was conducted. We used a very thin acupuncture needle (140–160 μm) and gentle sparrow pecking technique. This technique is very popular among the Japanese acupuncturists. Although needling to the throat sounds harmful, it produces a very comfortable sensation which projects deep into the throat and no severe adverse event was observed during the clinical trials. Indirect moxibustion is also very common and several commercial goods are available for consumers. Surface acupuncture (press tack needle) is also commonly used.

The analgesic properties of acupuncture are well known, however pain relief is not the only indication for acupuncture and moxibustion therapy. Basic research into acupuncture has focused on the pain inhibitory mechanism and several lines of evidence have been established. Various neurotransmitters and chemicals in the central nervous system that participate in the action of acupuncture analgesia and modification of cardiovascular function have also been clarified (see the review for details), (20). On the other hand, the nature of acupuncture points has not been well clarified until now. We have proposed a working hypothesis of peripheral action of acupuncture and moxibustion that sensitization of polymodal receptor is the key phenomenon to understand the nature of acupuncture points and efficacy of both acupuncture and moxibustion stimulation to similar acupuncture points (21). Excitation of the polymodal receptor by acupuncture and moxibustion may activate/modify the endocrine and immune systems as well as autonomic systems and might induce various curative effects.

The mechanism of acupuncture for common cold symptoms has not been clarified. However, the fundamental pathologic processes of the common cold are considered to be the biologic response to the infection by rhinoviruses. It is therefore, reasonable to assume that acupuncture stimulation activates the immune system to reduce common cold symptoms. Activation of NK cells has been proposed as an important basic mechanism for this phenomenon (22). Several studies have demonstrated that acupuncture stimulation enhances NK cell activities (23–25) and modulates the number and ratio of the immune cell types (17).

We used two types of questionnaires. One was CCD, binary information about common cold incidence and the other was the CCQ. The comparison of CCD and CCQ data showed several contradictions in the questionnaire. The subjects who answered ‘no’ in the CCD tended to mark ‘slight or moderate’ for several items in the CCQ. Figure 3 summarizes the results. This discrepancy might result from the criteria of CCD ‘yes’ in each subject area. We need a clearer manual for the descriptions in CCD questionnaires. On the other hand, the reliability test of CCQ was very high (Cronbach's α = 0.89). The positive result for the present RCT obtained using the GLM analysis of CCQ data, not CCD data, strongly supports the use of CCQ in future clinical trials (26).

In the present study we chose the sparrow pecking technique to the Y points at the throat. The Y points are not ordinary acupuncture points, but they have been frequently used for the treatment of throat pain in western Japan and the present procedure (gentle sparrow pecking with thin acupuncture needle), which is very common in Japanese acupuncture practice, was shown to be effective in the pilot study of this RCT (12). We conducted several training periods to teach the correct location and adequate manipulation for eliciting the acupuncture sensation to the throat. The Y point region at the throat is rich in blood vessels and nerves; however, few adverse events such as subcutaneous bleeding (0.8%) were reported. This event-ratio is higher than has been reported in Japan (0.14%). However, this figure includes acupuncture stimulation to the body and extremities (27). These data show the safety of thin acupuncture needling with careful gentle manipulation as commonly used in Japan even when inserted into tissues with numerous blood vessels and nerves.

In this series of clinical trials, students and staff of acupuncture schools were used as subjects. Only one project used aged subjects in a health care center. The majority of subjects had already experienced acupuncture treatment and were familiar with the sensation elicited by thin and shallow needling to the throat. We used no-treatment controls instead of sham acupuncture such as minimum acupuncture, or thin and shallow needling (28). We would like to highlight that previous experience with acupuncture and confidence in the efficacy of acupuncture may have influenced the results (29). When we began the present RCT we considered that it was more important to demonstrate the influence of acupuncture as a whole (including non-specific effects) on symptoms of the common cold. To our knowledge, this was the first RCT of its kind.

We assumed that the subjects’ expectation of the efficacy of acupuncture was very strong and a clear difference between the acupuncture and control groups might be obtained. Our expectation, however, was not fulfilled. The effects of acupuncture were not clear and a statistically significant negative effect was also found in one center in FTLE 2000 and a similar tendency was detected in the next project (FTLE2001). The reason for the negative result is not clear, but suggests that the subjects’ expectation was not as strong as we had supposed at the beginning of the trial. We should also consider that the subjects may have received additional acupuncture and moxibustion stimulation in the course of their training during the experimental periods. This additional treatment might have affected the results of differences among centers although the random allocation of the subjects should have reduced this variable.

The major benefit of using students as subjects was the very small dropout rate. Our consent form clearly described that the entry and interruption was completely of their own free will. We only paid a small amount of money (2000 Japanese ¥) to the registered subjects to cover their expenses and compensate them for their time but still avoiding financial inducement. We found the majority of subjects were interested in the methodology of this RCT and understood the importance of the accumulation of evidence for acupuncture efficacy by the RCT. This was important from an educational point of view and part of the reason behind, there being, so few dropout subjects.

It is well known that acupuncture and moxibustion therapy has developed as an individualized, tailor made therapy. Modern methodology diagnoses and treats similar symptoms in a very different way from acupuncture and moxibustion therapy. Regarding selection of intervention and point selection for the treatment of common cold symptoms, it was difficult to determine the standard procedure and acupuncture points for these projects. Inadequate procedure and point selection has always been pointed out as the cause for insufficient therapeutic results.

Recently, an experimental design of n-of-1 trial has been shown to be suitable for modalities that tailor the treatment to the individual and Guyatt et al. (30) has proposed the n-of-1 RCT (a paired treatment is randomly applied to the subject) as the top of the hierarchy for evidence-based medicine. Although the n-of-1 trial is a suitable design to determine the best treatment for each patient, its generalizability (external validity) is questionable. We have proposed a possible alternative design for n-of-1 trials based on group comparison (31). Recently Jackson et al. (32) demonstrated the efficacy of acupuncture by a series of n-of-1 trials with Bayesian analysis. Although this new Bayesian approach to data analysis of n-of-1 trials might be useful, we have no data available to analyze using these new statistical procedures at the moment. More effort is needed to develop an experimental design of n-of-1 trial and interventions that help to prevent the common cold.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their thanks to the staff and students of the centers involved in the study, especially to Yumiko Isobe, Si Yu and Takehisa Kojima in the pilot study of this project. We sincerely thank Morinomiya College of Arts and Sciences, Meiji University of Oriental Medicine, Tokyo College of Arts and Sciences, Kanagawa College of Art and Sciences, Meiji School of Acupuncture and Moxibustion and Kansai College of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (presently Kansai University of Acupuncture and Moxibustion) for their co-operation with the series of clinical trials on the common cold.

We also thank to Dr Oshitani, the Chairman of Sen-nen-kyu Co. Ltd for his kind offering of materials for indirect moxibustion. This study was supported by the foundation for training and licensure examination in anma-massage-acupressure, acupuncture and moxibustion.

References

- 1.Shah CP, Chipman ML, Pizaarello LD. The cost of upper respiratory tract infections in Canadian children. J Otolarygol. 1976;5:505–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zapka J, Averill BW. Self care for colds: a cost-effective alternative to upper respiratory infection management. Am J Public Health. 1979;69:814–16. doi: 10.2105/ajph.69.8.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fendrick AM, Monto AS, Nightengale B, Sarnes M. The economic burden of non-influenza-related viral respiratory tract infection in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:487–94. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jefferson TO, Tyrrell D. Antivirals for the common cold. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2001:CD002743. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Audera C, Patuly RV, Sander BH, Douglas RM. Mega-dose vitamin C in treatment of the common cold: a randomized controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2001;175:359–62. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard JC, Kantner TR, Lilienfield LS, Princiotto JV, Krum RE, Crutcher JE, et al. Effectiveness of Antihistamines in the symptomatic management of the common cold. JAMA. 1979;242:2414–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson JL, Lesho E, Peterson C. Zinc and the common cold: a meta-analysis revisited. J Nutr. 2000;130:1512S–1215S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.5.1512S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dockhorn R, Grossman J, Posner M, Zinny M, Tinkleman D. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the safety and efficacy of ipratropium bromide nasal spray versus placebo in patients with the common cold. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90:1076–82. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90126-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huangdi neijing (Inner canon of the Yellow Thearch)

- 10.Harper D. The conception of illness in early Chinese medicine, as documented in newly discovered 3rd and 2nd century B.B. manuscripts. Sudhoffs Archiv. 1990;74:10–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu JS. Acupuncture treatment of common cold. J Traditional Chin Med. 2000;20:227–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shichidou T, isobe Y, Yu shi, Kojima K, Inoue E, Kawakita K, et al. Preventive and curative effect of acupuncture on the symptoms of common cold -a pilot study of randomized controlled trials- Ido-no-Nihon. 2001;695:130–43. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawakita K, Shichidou T, Inoue E, Nabeta T, Kitakouji H, Aizawa S, et al. Preventive and curative effects of acupuncture on the common cold: a multicentre randomized controlled trial in Japan. Comp Ther Med. 2004;12:181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sumiya E, Fukushima K, Handa Y, Kawakita K, Tanzawa S. A randomized controlled trial of long term acupuncture treatment on the preventive effect on the symptoms of common cold-A pilot study at the Meiji School of Oriental Medicine- Oriental Medicine. 2004;10:7–12. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi N, Tsuru H, Egawa M, Matsumoto T, Kawakita K. Effects of indirect moxibustion on common cold symptoms in elderly subjets lived in nursing home: single-case experimental designs. J Jpn Soc Acupunct and Moxibustion. 2002;52:17–9. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawakita K, Sakai S, NakaZono Y, Kawase S, Oshitani T. Abstract of WFAS symposium. 2000. Functional characteristics of a newly developed sham moxibustion for the clinical research. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kishioka S, Toya K, Yamaguchi N, Shinohara S. Assessment of acupuncture upon physiological system-qualitative and quantitative assessment on leukocyto and lymphoid cell subsets after acupuncture. J Jpn Soc Acupunct and Moxibustion. 2002;52:17–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwemer G. General Linear models for multicenter clinical trials. Control Clin Trial. 2000;21:21–9. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(99)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallo P. Practical issues in linear models analyses in multicenter clinical trials. Biopharmaceutical Report. 1998;6:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma SX. Neurobiology of Acupuncture: Toward CAM. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:41–7. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawakita K, Shinbara H, Imai K, Fukuda F, Yano T, Kuriyama K. How do acupuncture and moxibustion act? - Focusing on the progress in Japanese acupuncture research - J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;100:443–59. doi: 10.1254/jphs.crj06004x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeda K, Okumura K. CAM and NK cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:17–27. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato T, Yu Y, Guo SY, Kasahara T, Hisamitsu T. Acupuncture stimulation enhances splenic natural killer cell cytotoxicity in rats. Jpn J Physiol. 1996;46:131–6. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.46.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe K, Shinohara S, Mizunuma K, Hayashida K, Itoi M, Kondou Y, Amagai T. Effects of acupuncture on the NK cell activities and subset in human peripheral blood. Bull Meiji Univ Orient Med. 1994;14:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu Y, Kasahara T, Sato T, Asano K, Yu G, Fang J, Guo S, Sahara M, Hisamitsu T. Role of endogenous interferon-γon the enhancement of splenic NK cell activity by electroacupuncture stimulation in mice. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;90:176–86. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shichidou T, Kawakita K, Inoue E, Nabeta T, Aizawa S, Nishida A, et al. Reliability testing of the questionnaire used in the clinical trials of acupuncture on the common cold symptoms. Ido-no-Nihon. 2001;693:97–105. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamashita H, Tsukayama H, Tanno Y, Nishijo K. Adverse events in acupuncture and moxibustion treatment: a six-ear survey at a national clinic in Japan. J Alt Comp Med. 1999;5:229–23. doi: 10.1089/acm.1999.5.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vincent C, Lewith G. Placebo controls for acupuncture studies. J R Soc Med. 1995;88:199–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birch S, Jamison RN. Controlled trial of Japanese acupuncture for chronic myofascial neck pain: Assessment of specific and nonspecific effects of treatment. Clin J Pain. 1998;14:248–55. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199809000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guyatt GH, Rennie D, editors. The evidence-based medicine working group. Use's; guides to the medical literature: a manual for evidence-based clinical practice. 4th ed. USA: AMA press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawakita K, Suzuki M, Namura K, Tanzawa S. A proposal for a simple and useful research design for evaluating the efficacy of acupuncture: multiple, randomized n-of-1 trials. JAM:Japanese Acupuncture and Moxibustion. 2005;1:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson A, MacPherson H, Hahn S. Acupuncture for tinnitus: A series of six n = 1 controlled trials. Comp Ther in Med. 2006;4:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]