Abstract

Two Steinernema isolates found in Louisiana and Mississippi were later identified as isolates of S. rarum. DNA sequences of ITS regions of the United States isolates are identical with sequences of Argentinean S. rarum strains Samiento and Noetinger and differ by two bases from the Arroyo Cabral isolate from Córdoba, Argentina. SEM observations revealed several new structures in the isolates from the US: female face views have a hexagonal-star perioral disc and eye-shaped lips; some females do not have cephalic papillae; lateral fields of infective juveniles are variable; there are two openings observed close to the posterior edge of the cloaca. Virulence of the US isolates to Anthonomus grandis, Diaprepes abbreviatus, Solenopsis invicta, Coptotermes formosanus, Agrotis ipsilon, Spodoptera frugiperda, and Trichoplusia ni and reproductive potential were evaluated in comparison with other heterorhabditid and steinernematid nematodes. Results such as particularly high virulence to S. frugiperda indicate that the biocontrol potential of the new S. rarum strains merits further study.

Keywords: DNA, entomopathogenic nematodes, host range, ITS, morphology, reproduction, Steinernema rarum, taxonomy

In a survey of nematodes in 21 pecan orchards in Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi, we found several isolates of Steinernema spp. (Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2003). Morphological, morphometric, and molecular studies of these nematode isolates showed that two isolates of the nematodes, one from Mississippi (isolate Jl) and one from Louisiana (isolate 17C), were S. rarum. This is the first report of this species in the United States. Although taxonomic and morphological aspects of the nematode species have been published (Doucet, 1986; Poinar et al., 1988), several important morphological and molecular characteristics have not been reported. In this paper, we use SEM photographs and molecular data to describe new isolates of the species and compare them with isolates collected from type locations in Argentina. Additionally, we provide biological data for the new strains pertaining to pathogenicity, virulence, and reproductive capacity in comparison to several other entomopathogenic nematode species.

Materials and Methods

Nematode collection: The US S. rarum isolates were collected from two locations during a survey for entomopathogens in southeastern pecan orchards (Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2003). One location was an orchard near Benton, LA, and the other in Rena Lara, MS. In each pecan orchard, five sample sites were chosen approximately 50 m from each other. About 4 kg of soil was collected from each site. In the laboratory, each sample was split into two plastic pots. Ten healthy greater wax moth larvae, Galleria mellonella, were added to one pot, and five pecan weevil larvae, Curculio caryae, to the other. Dead insects were removed every 5 d for 15 d and, the presence of nematodes was determined. We received several adults of the Argentinean isolates Arroyo Cabral and Noetinger fixed in 4% formalin in order to observe the precloacal ventral papilla by SEM. These isolates were collected from the same geographic region as the S. rarum type isolate (Espinal, elevation 250 m, in the province of Córdoba) (Doucet et al., 2003). The other isolate, Sarmiento (Charco forest, elevation 450 m), is also from Córdoba. All nematodes were identified to species using morphological, morphometric, and molecular techniques.

Nematode extraction: Nematodes collected from the field were maintained in the laboratory on G. mellonella. To obtain nematodes of different stages, 10 G. mellonella were exposed to 2,000 infective juveniles (IJ) in a petri dish (100 × 15 mm) lined with two moistened filter papers. First- and second-generation adult nematodes were obtained by dissecting infected insects 2 to 4 d and 5 to 7 d, respectively, after the insects died. Third-stage IJ were obtained when they emerged from the cadavers after 7 to 10 d. For observation and measurements, nematodes killed in warm water (40°C) were used. Twenty specimens of different stages were observed in this study. For the two US strains, means, standard deviation, ranges, and statistical analysis were obtained (SAS, Version 8.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) (P ≤ 0.05).

Scanning electron microscopy: Fifty females, 50 males, and 100 IJ were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde buffered with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate at pH 7.2 for 24 h at 8°C (Nguyen and Smart, 1995). They were post-fixed with 2% osmium tetroxide solution for 12 hr at 25°C, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, critical-point dried with liquid CO2, mounted on SEM stubs, and coated with gold. Spicules and gubernacula were prepared as suggested by Nguyen and Smart (1995).

Extraction of DNA and PCR amplification: DNA of S. rarum US strains was extracted from a single female using the method reported by Hominick et al. (1997). The ITS region of the ribosomal DNA was amplified by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as described by Nguyen et al. (2001), except the process was carried out in 25-μl reactions.

Sequencing: PCR products were purified using a QIA-quick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN Inc., Santa Clarita, CA). Purified DNA was sequenced at the DNA Sequencing Core Laboratory of the University of Florida. Sequences were edited and assembled using Sequencher 4.1 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI).

Phylogenetic analysis: Sequences of the 28S ribosomal DNA (D2/D3 regions) and the internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS) of Steinernema species have been used by different authors (Nguyen et al. 2001; Stock et al. 2001; Nguyen and Duncan, 2002; Nguyen and Adams, 2003; Stock and Koppenhöfer, 2003) in taxonomic and phylogenetic studies. In the present study, sequences of the ITS regions were used. The studies of D2/D3 regions of S. rarum US and Argentinean strains were reported by Nguyen and Adams (2003) and are not presented in this study.

DNA sequences used in this study: The sequences of the ITS regions used for the multiple sequence alignment were from: S. affine (GenBank accession number AF331912), S. bicornutum (AF121048); S. carpocapsae (AF121049); S. ceratophorum (AF440765); S. diaprepesi (AF440764); S. feltiae (AF121050); S. glaseri (AF1220115); S. intermedium (AF122016); S. monticolum (AF122017); S. neocurtillae (AF122018); S. oregonense (AF122019); S. rarum USA strain 17C (DQ221115); S. rarum USA strain Jl (DQ221116); Argentinean strains Sarmiento (AY275273), Noetinger (DQ221117), and Arroyo Cabral (AY275272); S. scapterisci (AF122020); and S. siamkayai (AF331917). The sequence of S. siamkayai was reported by Stock et al. (2001); all others were reported by Nguyen et al. (2001).

Sequences of studied species were aligned using the default parameters of Clustal X (Thompson et al., 1997), then optimized manually in MacClade 4.05 (Maddison and Maddison, 2002). Phylogenetic trees were obtained by maximum parsimony (MP) using PAUP, 4.0b8 (Swofford, 2002). All data were assumed to be unordered, all characters were treated as equally weighted, and gaps were treated as missing data. Maximum parsimony was performed with a heuristic search (simple addition sequence, stepwise addition, TBR branch swapping). Caenorhabditis elegans (for ITS regions, Adams et al., 1998; GenBank Accession number X03680) was treated as the outgroup taxon to resolve the relationships among other species. Branch support was estimated by bootstrap analysis (100 replicates) using the same parameters as the original search.

Biological analysis: Nematode reproductive capacity was assessed in last instar G. mellonella. Insects were individually exposed to approximately 50 IJ of H. bacteriophora, H. indica, and S. rarum (Jl) on 50-mm petri dishes that were lined with filter paper and moistened with a total of 370 ul water. After 3 d, infected insects were placed on White traps (Kaya and Stock, 1997). Infective juveniles were harvested until emergence ceased or was considered negligible (approximately 25 d post treatment), at which time the total number of IJ was estimated based on dilution counts (Shapiro et al., 1999). Treatment effects were evaluated through ANOVA (using square-root transformed means) and LSD (SAS, P ≤ 0.05). Because insect size can affect IJ yield (Flanders et al., 1996), reproductive capacity was recorded and analyzed based on both yield per insect and yield per gram of insect. There were 10 replicates (insects)/treatment.

Pathogenicity (ability to cause disease) and virulence (degree of pathogenicity) of the US S. rarum isolates were evaluated in a number of insect pests: the boll weevil, Anthonomus grandis; Diaprepes root weevil, Diaprepes abbreviatus; Agrotis ipsilon; cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni; fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda; red imported fire ant Solenopsis invicta; and Formosan subterranean termite, Coptotermes formosanus. All nematodes were cultured in parallel in last instar G. mellonella basedon procedures described by Kaya and Stock (1997). Virulence assays were conducted in soil cups using procedures described by Shapiro et al. (1999) and Shapiro-Ilan (2001). Cups (3- to 4-cm-diam., 3.5-cm deep) were filled with 40 g of a sandy soil except for D. abbreviatus and A. ipsilon assays, when cups were filled with 27 g of a sandy loam. Nematodes were pipeted onto the soil surface of each cup so that the final moisture was −0.05 bar, except for D. abbreviatus and A. ipsilon assays, which were standardized at field capacity (14% moisture). Due to low virulence and an inability to distinguish among treatments in soil assays (unpub. data), C. formosanus assays were conducted in petri dishes based on methods described by Kaya and Stock (1997); dishes (100 mm) were lined with filter paper moistened with 3 ml water. In all virulence assays, US S. rarum isolates were compared with Heterorhabditis bacteriophora (Hb strain) and S. carpocapsae (All strain), except A. ipsilon assays, which included S. feltiae (SN strain) rather than H. bacteriophora, and D. abbreviatus assays, which included S. riobrave (355 strain) rather than S. carpocapsae. Insect mortality was assessed after 14 d in all assays except A. ipsilon (3 d). The Mississippi strain of S. rarum (17C) was used in all assays except for A. ipsilon and D. abbreviatus, in which the Louisiana strain (Jl) was used. Replication and IJ concentration for A. grandis, C. formosanus, S. frugiperda, and T. ni are listed in the footnote section of Table 1. Six replicates of 10 insects were used for A. ipsilon (5 IJ/3rd instar) and D. abbreviatus (500 IJ/8th-10th instar). For S. invicta, there were 10 replicates of 10 3-4th instars, pupae, or workers per cup at 1,000 and 10,000 IJ/insect. Solenopsis invicta alates were assayed separately with 10 replicates of 20 insects (10 male and 10 female) at 1,000 and 10,000 IJ/insect. Differences in mean percentage insect mortality among treatments were detected through analysis of variance of (using arcsine transformed means) and LSD (SAS, P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Mortality of various pest insects following exposure to steinernematid and heterorhabditid nematodes.*

Results and Discussion

Dead G. mellonella turned red 2 or 3 d after they were exposed to the nematodes. The red color faded gradually in the White trap (White, 1927) and disappeared after the IJ emerged. This characteristic is unique for S. rarum and has not been reported for any other species of Steinernema.

SEM studies

First-generation females: Cephalic papillae in females were absent (Fig. 1D) in a number of specimens (10% for US isolate 17C). Perhaps this is why Doucet (1986) stated that females of this species did not have cephalic papillae. Cephalic papillae present in many specimens but are small and sometimes difficult to detect (Fig. 1A-C). Perioral disc hexagonal-star shaped (Fig. 1A-C). Labial papillae six, prominent. The hexagonal-star perioral disc makes each lip resemble an eye. The hexagonal-star shaped perioral disc and eye-shaped labial papillae are new features for S. rarum and have not been reported for other Steinernema spp. Amphids inconspicuous. Tail conoid (Fig. 1E). Vulva with surrounding annules (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

SEM photographs of some morphological structures of the first-generation females of S. rarum. A–C) Variation in face views of four females showing oral aperture, hexagonal-star perioral disc (po), six prominent eye-shaped lips with papillae (lp), and small cephalic papillae (cp). D) Head of a female showing labial papillae but without cephalic papillae. E,F) First-generation female tail and vulva. Scales: A,B = 6.67 μm, C = 7.5 μm, D,F = 10 μm, E = 30 μm.

First-generation males: Body C-shaped when relaxed (Fig. 2A). Head truncate; six labial, and four cephalic papillae prominent (Fig. 2B); amphid present. Tail tip with small mucron (Fig. 2D). Posterior region with 10–11 pairs of genital papillae: four to five pairs preanal (Fig. 2C), one pair lateral, two pairs adanal, three pairs postanal (Fig. 2D,F), and a single ventral preanal (Fig. 2E,F). Poinar et al. (1988) noted that in place of the single ventral preanal papilla in other species of Steinernema, double papillae were observed in S. rarum. Of isolates from the US and Argentina, males of S. rarum have only one preanal, ventral papilla (Fig. 3A,B).

Fig. 2.

SEM photographs of some structures of the first-generation males of S. rarum, US isolate 17C. A) Entire C-shaped body. B) Anterior region showing oral aperture, six labial papillae (lp), two of four cephalic papillae, and one of two amphids. C) Posterior region showing four preanal papillae, and protruding spicules. D) Ventral view of posterior region of a male showing seven pairs of genital papillae and a small mucron. E) Subventral view of posterior region of a male showing lateral, subventral, caudal dorsal papillae, and a single precloacal papilla (s). F) Ventral view of posterior region of a male showing pairs of genital papillae and a single precloacal papilla (s). Scales: A = 268 μm, B = 6 μm, C = 67 μm, D = 16.8 μm, E = 11.9 μm, F = 27.3 μm.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of SEM photographs of posterior regions of a male of S. rarum, Argentinean (first column) and US isolate 17C (second column). A,B) Both isolates show only one preanal genital papilla (arrows). C,D) Cloaca showing spicule tips and two unique openings posterior to the edge of cloaca. Note that the openings in Argentinean (arrows) strains are wide, but those of US strains (arrows) are slit-like in shape. Scales: A = 16.7 μm, B = 27.3 μm, C = 3 μm, D = 6 μm.

Two special structures were observed in S. rarum: two openings present on posterior lip of cloaca of both the US and Argentinean strains. The shape is sometimes slit-like, sometimes pore-like (Fig 3C,D). These two structures are reported the first time for Steinernema and have not been observed on other Steinernema species.

Spicules and gubernacula (Fig. 4) of the US isolates differ in shape from those of other species of Steinernema. Spicule head short, velum prominent, extending more than two-third of blade. Posterior third of spicule straight, ventral side with a depression area close to spicule tip (Fig. 4B). Gubernaculum tapering anteriorly to a somewhat ventrally curved end. Corpus separated posteriorly (Fig. 4D). Cuneus rod-like, a good character for species identification. General shape of spicules of Argentinean isolates are similar to those of US strains (Fig. 4E,F).

Fig. 4.

SEM photographs of spicules and gubernacula of S. rarum, US and Argentinean isolates. A–C) US strain 17C, all spicules are not similar in shape, with short head, prominent velum. D) Gubernaculum, ventral view with rod-like cuneus, and posterior end separated. E,F) Argentinean strain, spicules are not similar in shape. Scales: A–D = 15 μm, E,F = 12 μm.

Infective juveniles: Head not annulated, labial papillae not observed, four cephalic papillae prominent, amphid pronounced (Fig. 5A). Lateral field is very variable. Lateral field pattern begins with two ridges. Near excretory pore level, the number of ridges is eight (Fig. 5B,C). The two submarginal ridges at mid body are not raised as others and difficult to see, only six are seen under light microscope. Posterior part of the lateral field is very variable. Sometimes (5%) the number of ridges becomes 10 (Fig. 5D). Near anus the number of ridges usually becomes six then two at some annules anterior (Fig. 5E) or posterior (Fig 5F) to phasmid. In the posterior part of some individuals (about 10%), the pattern changes into two marginal bands and a central large and smooth band (Fig. 5G). Finally, the lateral field turns into one smooth band. In about 10% of the population, lateral field has two wide ridges at the beginning and then turns into a smooth band that extends to the end of lateral field (Fig. 5H).

Fig. 5.

SEM photographs of infective juveniles of S. rarum, US isolate 17C. A) Head showing three of four prominent cephalic papillae (c), one of two amphids (a). B) Lateral field showing two ridges anteriorly followed by eight ridges. C) Lateral field at mid-body with eight ridges, two submarginal ridges (2, 7) difficult to see. D) Posterior part of the body showing lateral field with 10 ridges. E,F) Near anus, the number of ridges in lateral field becomes six, then decreases to four and to two at some annules anterior (E) and posterior (F) to phasmid. G) In one form, lateral field changes into three bands, two marginal ones and a large central band, and then becomes one band near tail tip. Scales: A = 3.74 μm, B = 3.75 μm, C, D, E = 6 μm, F = 5.98 μm, G = 4.24 μm, H = 10 μm, and I = 250 μm. H) Lateral field showing two wide ridges anteriorly and then turning into a smooth band. I) IJ with spiral shape at room temperature.

One noticeable character of the US isolates is that at room temperature (25°C) most IJ are spiral-shaped (Fig. 5I).

Morphometric studies

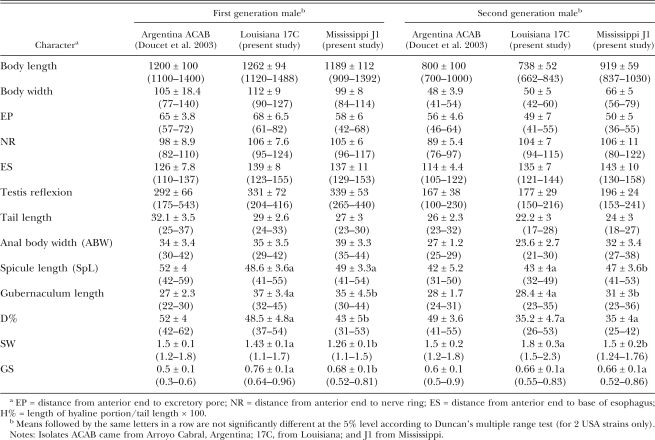

Morphometrics of adults and IJ of S. rarum are presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4. Character differences between the two US strains are not significant (Table 2, 3).

Table 2.

Comparative morphometrics (in μm) of males of Steinernema rarum USA and Argentina strains (n = 20).

Table 3.

Comparative morphometrics (in μm) of females of Steinernema rarum strains USA (17C and J1), and Argentina strain (ACAB).

Table 4.

Comparative morphometrics (in μm) of infective juveniles of four strains of Steinernema rarum, USA (17C and J1), and Argentina (ACAB, NOE) (n = 20).

Although the body length of females and males of Argentinean isolates are different from those of the US isolates, most diagnostic characteristics of IJ are similar. For males, spicule lengths of males of the first generation of the two isolates are not significantly different, but gubernaculum length, SW, GS, and D% are significantly different (Table 2). For second-generation males, spicule, gubernaculum lengths, and SW are significantly different, but for D% and GS ratios, the differences are not significant. Local conditions may play a role in the differences as one isolate was from Louisiana and the other from Mississippi. Some differences were observed between males of the Argentinean and US isolates, such as gubernaculum length, D%, and GS ratio, but comparable data of isolates from Argentina are not available for statistical comparison. Data from Doucet et al. (2003) were used for comparison with US strains in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Phylogenetic characterization

The sequences of the ITS regions of the two S. rarum US strains were identical in length to each other and to isolates Sarmiento and Noetinger and very similar to Arroyo Cabral from Argentina (sequence length = 935 bp, ITS1 = 251 bp, ITS2 = 312 bp; Table 5). Phylogenetic relationships between Steinernema species with short and medium body lengths (446 to 769 μm) are shown in Figure. 6. Steinernema rarum from the US and Argentina form a monophyletic group, but with an unresolved relationship to the other taxa. This tree topology for ITS regions is similar to that produced by LSU D2/D3 regions as reported by Nguyen and Adams (2003). To compare the differences between S. rarum US strains and other Steinernema species, we found that S. rarum 17C and S. riobrave have the fewest substitution/indel events with 166 bp (Table 5); the greatest number of changes is 296 bp between S. rarum 17C and S. bicornutum.

Table 5.

Pairwise distances of ITS regions between taxa. Below diagonal: Total character differences. Above diagonal: Mean character differences (adjusted for missing data)

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic relationships among 13 short-body isolates of Steinernema species based on analysis of ITS regions. Previous work has shown this clade to be monophyletic, with the exception of S. intermedium and S. rarum (Nguyen and Adams, 2003). Note that the four isolates of Steinernema rarum form a monophyletic group. The numbers at the nodes represent bootstrap proportions where greater than 50%.

Pairwise distances of the ITS regions showed that there are only two base-pair differences between S. rarum 17C and isolate Arroyo Cabral and no difference between isolate 17C and Argentinean isolates Sarmiento and Noetinger. In a study of phylogenetic relationships between 81 ITS-region sequences of Steinernema spp., Spiridonov et al. (2004) reported that the intra-specific variations in many species are quite large; among strains of S. affine, there were two to five base pairs different; among S. kraussei, from one to 21 bp; and an isolate of S. bicornutum from Russia had 17 bp differences from the topotype isolate (Yugoslavia). We previously found intra-specific differences that ranged from 0 to 14 bp among 12 isolates of S. riobrave (from Texas and Louisiana), 0 to 20 bp among eight isolates of S. feltiae, and one to six bp among 10 isolates of S. carpocapsae (unpubl. data). All of these isolates were reproductively compatible with members of their respective species based on cross-breeding tests. Thus, the intra-specific distances between sequences of ITS regions of Steinernema species, as delimited by the biological species concept, range from 0 to as many as 21 base pairs. These ITS distances are much greater than those of LSU rDNA sequences reported by Stock et al. (2001) and Nguyen and Adams (2003), with distances between two species as low as one base pair (between S. hermaphroditum and S. scarabaei, and S. glaseri and S. cubanum). There are no differences between any of the S. rarum isolates at the D2/D3 locus (AY253296, DQ221118, DQ221119). Additionally, as shown in Table 5, interspecific differences among nematode species with short and medium body lengths (446–769 μm) are large. The fewest differences occur between S. carpocapsae and S. scapterisci with 115 base pairs different; the greatest occur between S. bicornutum and S. intermedium with 315 base pairs different.

Comparison of intraspecific variation (Table 5; Fig. 6) suggests that the US isolates are S. rarum. Variation between isolates of this species is consistent with morphological, morphometric, and molecular variation observed in other species of Steinernema. In this case, crossbreeding studies could have been done to explore reproductive incompatibility (since live cultures of the requisite isolates were unavailable for this study). However, while such studies may shed light on the potential for gene flow, they are irrelevant to species ontology (Adams, 1998). Differentially fixed autapomorphies among distinct evolutionary lineages do provide evidence of historical lineage independence, and thus speciation events. However, the acquisition of a single autapomorphy in one lineage without subsequent evolution of an autapomorphy in the sister taxon is insufficient to delimit species and reflects variation among populations within a species (Adams, 1998, 2001). This is the pattern of variation observed among the isolates of S. rarum sampled for this study. Given the low number of populations sampled, low number of autapomorphies (from a single genetic locus; one autapomorphy for the Arroyo Cabral isolate), and relatively high level of intraspecific variation at this locus observed in several other members of the genus, we suggest that as of yet there is insufficient evidence to infer lineage independence.

Biological analysis

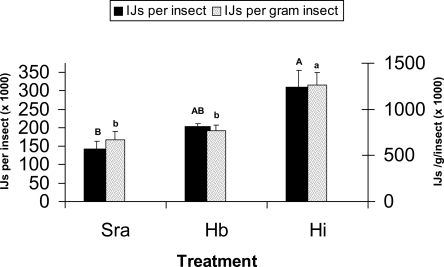

Differences in reproductive capacity were detected among nematodes. Analysis of IJ production per insect indicated a higher yield from H. indica than S. rarum with H. bacteriophora being intermediate and not different from the other species (Fig. 7). Analysis of yield per gram of insect, however, indicated higher reproduction in H. indica than both S. rarum and H. bacteriophora (which were not different from each other) (Fig. 7). The results confirm that greater resolution in reproductive capacity can be obtained when standardizing yield on a per-weight basis. The reproductive capacities observed for S. rarum and H. bacteriophora in this study are consistent with other reports for these nematode species (Grewal et al., 1994; Koppenhöfer and Kaya, 1999) and confirm the ability of H. indica to produce high yields (Shapiro et al., 1999). Although the yield of S. rarum in G. mellonella was less than H. indica, these results should not be taken as a hindrance to mass production. Indeed, production in S. rarum appears to be similar to H. bacteriophora (a commercially available species) and greater than other species that have been successfully commercialized, e.g., S. feltiae (Grewal et al., 1994). Productivity of S. rarum in liquid culture remains to be determined.

Fig. 7.

Infective juvenile (IJ) nematode production in Galleria mellonella. Sra = Steinernema rarum (J1 strain); Hb = Heterorhabditis bacteriophora (Hb strain); Hi = H. indica (Homl strain). Bars with the same uppercase and lowercase letters are not significantly different for IJ per insect and IJ per gram insect, respectively (LSD, P ≤ 0.05).

Virulence of S. rarum to A. grandis, C. formosanus, S. frugiperda, and T. ni was similar or greater than the other nematodes tested (Table 1). Differences in virulence among nematodes were detected in all hosts except for T. ni (Table 1). Steinernema rarum and S. feltiae caused greater mortality in A. grandis than S. carpocapsae at the lower concentration tested (Table 1). Steinernema rarum caused greater mortality in C. formosanus than S. carpocapsae (at the higher concentration) but not H. bacteriophora (Table 1); S. carpocapsae has been previously shown to have some potential for termite control (Epsky and Capinera, 1988).

Overall, S. rarum was more virulent to S. frugiperda than the other nematodes tested. Specifically, in all stages of S. frugiperda assayed, S. rarum was more virulent than S. carpocapsae and/or H. bacteriophora at one or more concentration, e.g., at 50 IJs/insect, S. rarum virulence to 3–4th instars and prepupae was superior to the other nematodes (Table 1). Furthermore, in no instance did S. carpocapsae or H. bacteriophora cause greater mortality than S. rarum (Table 1). Richter and Fuxa (1990) reported significant suppression of S. frugiperda with S. carpocapsae under field conditions. Thus, we believe the potential for S. rarum against this pest is promising indeed.

In contrast to the results indicated in Table 1, S. rarum exhibited relatively poor virulence to several hosts. Percentage D. abbreviatus mortality was significantly higher in H. bacteriophora and S. riobrave treatments (81.7 ± 7.0 and 95.0 ± 2.2, respectively) than in the S. rarum treatment (41.1 ± 4.7), which was not different from the control (25.0 ± 7.2). Percentage A. ipsilon mortality was greater in S. carpocapsae (90.0 ± 5.1) than in H. bacteriophora (40.0 ± 9.7) or S. rarum (45.0 ± 5.6), all of which were greater than the control (1.7 ± 1.7). Similar to our results, S. carpocapsae was also more virulent than H. bacteriophora in a previous study (Capinera et al., 1988). Although pathogenicity to all S. in-victa stages was detected in all nematodes (as indicated by a mortality difference in at least one concentration compared, data not shown), virulence to all stages of S. invicta was low for all nematodes tested. Even with 10,000 IJ/insect, the highest percentage S. invicta mortality was 26.0 ± 6.4 (from H. bacteriophora in 3–4th instars). The S. invicta mortality levels we observed were lower than those reported by Drees et al. (1992), but in general our findings agree with others that indicate the potential for field suppression of S. invicta with entomopathogenic nematodes is limited (Jouvenaz et al., 1990; Drees et al., 1992).

In summary, although direct comparisons among the hosts themselves were not made in our study, virulence assays generally appear to be in agreement with Koppenhöfer and Kaya's (1999) finding (using the Argentinean strain Sargento Cabral) that the nematode is well suited to lepidopteran hosts. Our findings also indicate certain curculionids (e.g., A. grandis) or other Coleoptera may be substantially susceptible. Clearly, further studies on biocontrol potential in lab and field studies are warranted. In particular, our observations of high S. rarum virulence to S. frugiperda are especially intriguing and should be pursued further.

Footnotes

Florida Agricultural Experiment Station Journal series No R-10477.

The authors thank G. C. Smart, Jr. and A. C. Tarjan for reviewing the manuscript.

Literature Cited

- Adams BJ. Species concepts and the evolutionary paradigm in modern nematology. Journal of Nematology. 1998;30:1–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams BJ. The species delimitation uncertainty principle. Journal of Nematology. 2001;33:153–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams BJ, Burnell AM, Powers TO. A phylogenetic analysis of Heterorhabditis (Nemata: Rhabditidae) based on internal transcribed spacer 1 DNA sequence data. Journal of Nematology. 1998;30:22–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet MMA. A new species of Neoaplectana Steiner, 1929 (Nematoda: Steinernematidae) from Córdoba, Argentina. Revue de Nématologie. 1986;9:317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Doucet MMA, Bertolotti MA, Doucet ME. Morphometric and molecular studies of isolates of Steinernema rarum (Doucet, 1986) Mamaya, 1988 (Nematoda: Steinernematidae) from the province of Córdoba, Argentina. Journal of Nematode Morphology and Systematics. 2003;6:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Capinera JL, Pelissier D, Menout GS, Epsky ND. Control of black cutworm, Agrotis ipsilon (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), with entomogenous nematodes (Nematoda: Steinernematidae, Heterorhabditidae) Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 1988;52:427–435. [Google Scholar]

- Drees BM, Miller RW, Vinson SB, Georgis R. Susceptibility and behavioral response of red imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) to selected entomogenous nematodes (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae & Heterorhabditidae) Journal of Economic Entomology. 1992;85:265–370. doi: 10.1093/jee/85.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epsky ND, Capinera JL. Efficacy of the entomogenous nematode Steinernema feltiae against a subterranean termite, Reticulitermes tibialis (Isoptera: Rhinotermidae) Journal of Economic Entomology. 1988;81:1313–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal PS, Selvan S, Gaugler R. Thermal adaptation of entomopathogenic nematodes—niche breadth for infection, establishment, and reproduction. Journal of Thermal Biology. 1994;19:245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Flanders KL, Miller JM, Shields EJ. In vivo production of Heterorhabditis bacteriophara ‘Oswego’ (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae), a potential biological control agent for soil-inhabiting insects in temperate regions. Journal of Economic Entomology. 1996;89:373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Hominick WM, Briscoe BR, del Pino FG, Heng J, Hunt DJ, Kozodoy E, Mracek Z, Nguyen KB, Reid AP, Spiridonov S, Sturhan D, Waturu C, Yoshida M. Biosystematics of entomopathogenic nematodes: Current status, protocols, and definitions. Journal of Helminthology. 1997;71:271–298. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x00016096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouvenaz DP, Lofgren CS, Miller RW. Steinernematid nematode drenches for control of fire ants, Solenopsis invicta, in Florida. Florida Entomologist. 1990;73:190–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya HK, Stock SP. Techniques in insect nematology. In: Lacey LA, editor. Manual of techniques in insect pathology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 281–324. [Google Scholar]

- Koppenhöfer AM, Kaya HK. Ecological characterization of Steinernema rarum . Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 1999;73:120–128. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1998.4822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP, Maddison DR. Massachusetts Sunderland: Sinauer; 2002. MacClade, v. 4.0. [Google Scholar]

- Mamiya Y. Steinernema kushidai n. sp. (Nematoda: Steinernematidae) associated with scarabaeid beetle larvae from Shizuoka, Japan. Applied Entomology and Zoology. 1988;23:313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KB, Adams BJ. SEM and systematic studies of Steinernema abbasi Elawad et al., 1997 and S. riobrave Cabanillas et al., 1994 (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) Zootaxa. 2003;179:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KB, Duncan LW. Steinernema diaprepesi n. sp. (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae), a parasite of the citrus root weevil Diaprepes abbreviatus (L) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) Journal of Nematology. 2002;34:159–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KB, Smart GC., Jr Scanning electron microscope studies of Steinernema glaseri (Nematoda: Steinernematidae) Nematologica. 1995;41:183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KB, Maruniak J, Adams BJ. The diagnostic and phylogenetic utility of the rDNA internal transcribed spacer sequences of Steinernema . Journal of Nematology. 2001;33:73–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poinar GO, Jr, Mracek Z, Doucet MMA. A reexamination of Neoaplectana rara Doucet, 1986 (Steinernematidae: Rhabditidae) Revue de Nématologie. 1988;11:447–449. [Google Scholar]

- Richter AR, Fuxa JR. Effect of Steinernema feltiae on Spodoptera frugiperda and Heliothis zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in corn. Journal of Economic Entomology. 1990;83:1286–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro DI, Cate JR, Pena J, Hunsberger A, McCoy CW. Effects of temperature and host range on suppression of Diaprepes abbreviatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) by entomopathogenic nematodes. Journal of Economic Entomology. 1999;92:1086–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro-Ilan DI. Virulence of entomopathogenic nematodes to pecan weevil larvae Curculio caryae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in the laboratory. Journal of Economic Entomology. 2001;94:7–13. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-94.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro-Ilan DI, Gardner WA, Fuxa JR, Wood BW, Nguyen KB, Adams BJ, Humber RA, Hall MJ. Survey of entomopathogenic nematodes and fungi endemic to pecan orchards of the Southeastern United States and their virulence to the pecan weevil (Coeloptera: Curculionidae) Environmental Entomology. 2003;32:187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Spiridonov SE, Reid AP, Podrucka K, Subbotin SA, Moens M. Phylogenetic relationships within the genus Steinernema (Nematoda: Rhabditida) as inferred from analyses of sequences of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region of rDNA and morphological features. Nematology. 2004;6:547–566. [Google Scholar]

- Stock SP, Campbell JF, Nadler SA. Phylogeny of Steinernema Travassos, 1927 (Cephalobina: Steinernematidae) inferred from ribosomal DNA sequences and morphological characters. Journal of Parasitology. 2001;87:877–889. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[0877:POSTCS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock SP, Koppenhöfer AM. Steinernema scarabaei n. sp. (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae), a natural pathogen of scarab beetle larvae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) from New Jersey. Nematology. 2003;5:191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates; 2002. PAUP* Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods) [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White GF. A method for obtaining infective nematode larvae from culture. Science. 1927;66:302–303. doi: 10.1126/science.66.1709.302-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]