Abstract

The nematicidal activities of ammonium sulfate, chicken litter and chitin, alone or in combination with neem (Azadirachta indica) extracts were tested against Meloidogyne javanica. Soil application of these amendments or the neem extracts alone did not reduce the root galling index of tomato plants or did so only slightly, but application of the amendments in combination with the neem extracts reduced root galling significantly. Soil analysis indicated that the neem extract inhibited the nitrification of the ammonium released from the amendments and extended the persistence of the ammonium concentrations in the soil. In microplot experiments, tomato plants were grown in pots filled with soils from the treated microplots. The galling indices of tomato plants grown in soil treated with ammonium sulfate or chicken litter in combination with the neem extract or a chemical nitrification inhibitor were far lower than those of plants grown in the control soil or in soil treated with chicken litter, neem extract or nitrification inhibitor alone. However, plants grown in the microplots showed only slight reductions in galling, probably because the soil amendments were inadequately mixed compared to their application in the pot experiments. The extended exposure of nematodes to ammonia as a result of nitrification inhibition by the neem extracts appeared to be the cause of the enhanced nematicidal activity of the ammonia-releasing amendments.

Keywords: ammonia, ammonium sulfate, Azadirachta indica, chicken litter, chitin, neem, nitrification, nitrification inhibitor, soil amendments

Use of organic soil amendments to control soil-borne diseases, including plant-parasitic nematodes, is an established agricultural practice. Amendments may increase soil populations of microorganisms antagonistic to nematodes, but are also known to release several toxic compounds, directly or during their decomposition in soil. Among compounds released during the decomposition processes are several organic acids that are nematicidal in acidic soil environments (Sayre et al., 1965). In alkaline soils, ammonia is highly effective in controlling nematodes and fungi. Ammonia-releasing materials, including both organic and inorganic compounds, have been used as both nematicides and fungicides (Eno et al., 1955; Smiley et al., 1970; Tsao and Oster, 1981; Rodríguez-Kábana et al., 1982; Rodríguez-Kábana, 1986; Rodríguez-Kábana et al., 1987; Oka et al., 1993; Oka and Pivonia, 2002). A limitation to the use of ammonia-releasing materials for nematode control is that large amounts are needed, which are often phytotoxic (Rodríguez-Kábana et al., 1987; Stirling, 1991; Oka and Pivonia, 2002). Moreover, soil pH greatly affects the nematicidal activity of ammonia-releasing amendments; under acidic conditions almost all ammonia (NH3) released into the soil is ionized to ammonium ion (NH4 +), which is not nematicidal (Warren, 1962; Duplessis and Kroontje, 1964). Usually, smaller amounts of such ammonia-releasing amendments are required for nematode control in neutral to alkaline soils than in acidic soils, and temporary elevation of the soil pH effectively increased the nematicidal activity of ammonia-releasing amendments against Meloidogyne javanica (Oka et al., 2006a, 2006b). Another factor that limits the use of ammonia is its instability in soil; ammonia and ammonium are oxidized to nitrite and then to nitrate by soil microorganisms in processes known as nitrification. Two main groups of bacteria are involved in nitrification; Nitrosomonas spp. oxidize ammonia to nitrite and subsequently Nitrobacter spp. oxidize the nitrite to nitrate (Focht and Verstrate, 1977), which, in contrast to ammonia, is not nematicidal. Several compounds have been tested as nitrification inhibitors to prevent ammonium nitrogen from leaching from the soil. Nitrapyrin has been reported to be one of the most effective of these (Goring, 1962; Swezey and Turner, 1962). In a previous study, the nematicidal activity of ammonia-releasing organic amendments or ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH) was enhanced by adding nitrapyrin, which maintained the ammonia concentration in the soil for longer periods (Oka and Pivonia, 2003). However, nitrapyrin cannot be used in organic farms where organic soil amendments are used as fertilizers and for controlling nematodes and soil-borne fungal diseases.

Several medicinal and herbal plants, such as Mentha spicata, Artemisia annua, neem (Azadirachta indica) and karanja (Pongamia glabra), have been tested for their nitrification-inhibiting efficacy (Sahrawat and Mukerjee, 1977; Usha and Patra, 2003). In particular, karanja and neem extracts have been found to be relatively effective in inhibiting nitrification (Sahrawat and Mukerjee, 1977; Gnanavelrajah and Kumaragamae, 1998, 1999). Several parts of neem trees and their extracts are known to exhibit insecticidal, fungicidal and nematicidal activities (Mojumdar, 1995; Raguraman et al., 2004; Suresh et al., 2004), and many neem-based pesticidal formulations have been developed and marketed. In the present study, enhancement of the nematicidal activity of ammonia-releasing compounds in combination with neem extracts that have nematicidal activity and may also inhibit nitrification was tested.

Materials and Methods

Nematode: Meloidogyne javanica eggs were extracted from infected tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum cv. Daniela, Hazera Genetics, Israel) roots with a 2% sodium hypochloride solution (Hussey and Barker, 1973). Second-stage juveniles (J2) emerging from eggs spread on a 30-um-pore sieve were collected daily and stored at 15°C. J2 less than 5-d-old were used in experiments.

Chemicals: The ammonium sulfate (AS) used in growth chamber and field microplots experiments was purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and from Fertilizers and Chemicals (Haifa, Israel), respectively. Azatin EC® (AgryDyne, Salt Lake City, UT), which contains 3% azadirachtin and 27% other neem compounds, was used in the growth chamber experiments. Easydor® (EFAL Agro, Netanya, Israel), which contains 3% azadirachtin, was used in the field micro-plot experiments. N-Serve 24E® (Dow AgroSciences LLC, Indianapolis, IN), which contains 21.9% nitrapyrin and 2.4% related chlorinated pyridines, was used in field microplot experiments as a chemical nitrification inhibitor.

Organic compounds: Technical chitin flakes (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) prepared from crab shells were pulverized by a cyclone sample mill before use. Chicken litter from a broiler farm (Ramat-Negev, Israel) contained N-NH4 + at 2,324 mg/kg, N-NO3 − at 74 mg/kg and phosphorus at 10.5 g/kg and had pH 7.8 and EC 13.5 (dS/m). The chicken litter was also pulverized before use.

Pot experiments: The AS was mixed with dune sand (pH 8.5, organic matter < 0.1%) at an N concentration of 75 mg/kg, with or without Azatin at concentrations in sand of 0.67, 0.33, 0.17 and 0.08 g/kg, which were equivalent to 0.2, 0.1, 0.05 and 0.025 g neem extracts/kg sand. The AS and/or Azatin were dissolved in 100 ml of water and added to 1 kg untreated dry sand. The soil, packed in 700-cm3 plastic pots, was inoculated with 1,000 M. javanica eggs and 1,500 J2/pot by injecting 5 ml of a nematode suspension into five 5-cm-deep holes. The soil in the pot was then covered with a polyethylene sheet and incubated for 7 d at 27 ± 2°C. Four-week-old tomato seedlings (cv. Daniela) were transplanted into the pots, maintained in a growth chamber at 27 ± 2°C with 13-hr days, and fertilized with 50 ml of a 0.1% solution of N-P-K fertilizer (20–20–20) every 2 wk. Fresh shoot weights, numbers of nematode eggs per plant and root galling indices (GI: 0–5) were recorded 6 wk after planting. The GI of roots was assessed on a 0 to 5 scale: 0, no galled roots; 1,120% of the roots galled; 2, 21–40% galled; 3, 41–60%; 4, 61–80%; and 5, 81–100% of the roots were galled. The numbers of nematode eggs on the root systems were counted after removal from the tomato roots with 2% sodium hypochlorite (Hussey and Barker, 1973).

In the second experiment, the soil was mixed with the chicken litter at concentrations (dry basis) of 4.0 and 8.0 g/kg, with or without Azatin at a neem extract concentration of 0.05 g/kg. The chicken litter was first mixed with dry sand, and the Azatin dissolved in 100 ml of water was added to the mixture. The soil packed in the pot was inoculated with M. javanica eggs and J2 and covered and incubated in the growth chamber for 7 d, as in the first experiment. The tomato seedlings were transplanted in the soil, and fresh shoot weights, numbers of nematode eggs and root GI were recorded as described above.

In the third experiment, chitin powder was mixed with the soil at a concentration of 4.0 g/kg, and the soil was inoculated with nematodes as described above. Five days later, the neem extract in Azatin dissolved in 10 ml water was added to the soil at 0.025 g/kg. Tomato seedlings were transplanted into the soil 5 d later and were kept in the growth chamber, as in the first and second experiments. Fresh shoot weight, number of nematode eggs and root GI were recorded 6 wk after planting. These three experiments included five replicates per treatment and were repeated twice. Untreated, nematode-inoculated sand served as a control.

Effect of neem extract on nitrification: A solution of AS in 80 ml of water was mixed into 800 g of untreated dry sand at an N concentration of 75 mg/kg, with or without Azatin at a neem extract concentration of 0.025 g/kg. The soil was packed in 700-cm3 plastic pots, covered with a polyethylene sheet, and maintained in the growth chamber at 27 ± 2°C. Concentrations of water-extractable ammonium and nitrate in the soils and the soil pH were recorded 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, 14 and 21 d after treatment by reciprocal shaking of 2.0 g (dry base) of the soil in 20 ml water at 100 rpm for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 3,600g for 15 min. Analysis was done with a QuikChem 8000 Flow Injection Analyzer (Lachat Instruments, Milwaukee, WI). Each treatment had four replicates.

In another experiment, the chitin powder was mixed into 800 g of untreated dry sand at a concentration of 4.0 g/kg. Azatin dissolved in 80 ml water was mixed into the sand immediately, at a neem extract concentration of 0.05 g/kg, or was mixed in 5 d later, dissolved in 10 ml of water. The soils, packed in pots covered with polyethylene sheets, were maintained at 27 ± 2°C in the growth chamber. The concentrations of water-extractable ammonium and nitrate in the soils and the soil pH were recorded 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21 and 28 d after treatment as described above. These two experiments had four replicates per treatment and were repeated twice.

Field microplot experiment: Thirty microplots, each a 1-m2 × 1.1-m-deep plastic pipe buried in the field, contained M. javanica-infested sandy soil at pH 8.5, EC = 0.6 dS/m. A 1:5 soil:water extract of the soil contained clay:silt:sand in proportions of 2:1:97, respectively. The microplots were divided into six treatments: 1) untreated control; 2) incorporation of 4.2 kg (dry base) of the chicken litter into the soil at approximately 0.4% (w/w) to a depth of 35 cm; 3) incorporation of 68 g of Easydor dissolved in 5 liters of water; 4) incorporation of 3.0 g of nitrapyrin dissolved in 5 liters of water; 5) incorporation of 4.2 kg of the chicken litter and 68 g Easydor in 5 liters of water; 6) incorporation of 4.2 kg of the chicken litter and 3.0 g of nitrapyrin in 5 liters of water. The plots of treatments 1 and 2 received 5 liters of water after treatment. The number of J2 extracted from soil taken from a 10- to 20-cm depth and extracted using the Baermann funnel method (Barker, 1985) was 3.2 ± 3.7 (n = 15)/50 g of soil, before treatment. All the plots were covered with a plastic sheet immediately after the treatment and were shaded with a 50% light-cut black net in order to minimize the effect of soil solarization. Seven days after the treatments, the plastic sheet was removed. One 700-cm3 plastic pot was filled with soil of each microplot from a depth of 10 to 30 cm, and one tomato seedling (cv. Daniela) was transplanted into each pot. The pots were then kept in the growth chamber at 27 ± 2°C with 13-hr days and fertilized with 50 ml of a 0.1% solution of fertilizer 20–20–20 (N–P–K) every 2 wk. Fresh shoot weights, numbers of nematode eggs per plant and root galling indices (GI: 0–5) were recorded 6 wk after planting.

In the microplots, four tomato seedlings (cv. Daniela) were transplanted into each microplot, irrigated with 2.0 liters of water via a drip irrigation system every 2 d, and fertilized with 5.0 g of the fertilizer once a week. The plants were uprooted 2 mon after planting, and fresh shoot weight and root-galling indices on a 0 to 10 scale (0 = no galls and 10 = all roots severely galled) were recorded (Bridge and Page, 1980). This experiment had five replicates per treatment; untreated soil served as a control.

The experiment was replicated in other microplots, each comprising a 1-m2 × 1.2-m-deep concrete tube buried in the field. The soil in the microplots had a pH 8.6, EC 2.1 dS/m, and in a 1:5 soil:water extract contained clay:silt:sand in the proportions 15:5:80, respectively; it was infested with M. javanica. The number of J2 from soils taken from a 10- to 20-cm depth and extracted by the Baermann funnel method before treatment was 12.3 ± 8.9 (n = 15)/50 g soil. Thirty microplots were divided into six treatments, which were the same as those in the first experiment. Tomato (cv. Daniela) plants were transplanted into pots filled with soils taken from the microplots and into the microplots as in the first trial. Fresh shoot weights, root-galling indices and numbers of nematode eggs were recorded. The numbers of eggs were recorded only for the plants grown in the pots.

Data analysis: Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA), and means were separated according to the Tukey-Kramer HSD test (α = 0.05). Factorial analysis was used to evaluate the significance of the interaction of the main effects. The two main effects were ammonia source (AS, chicken litter or chitin) and nitrification inhibitors (neem extracts or nitrapyrin). If the same trend was observed in two trials of an experiment, the data were combined. A significant interaction indicated that one factor (e.g., ammonia source) has an influence on the effects elicited by the other factor (nitrification inhibitors) and that the resulting combined effect was greater than the sum of the separate effects of the two factors. All calculations were performed with the JMP software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

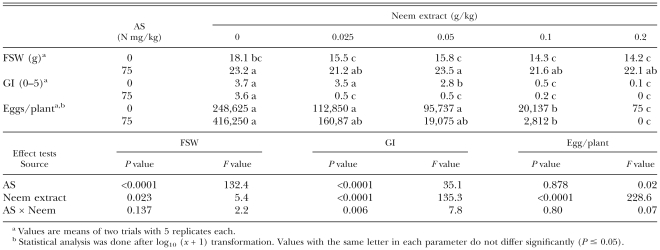

Pot experiments: Azatin, a neem extract product, was nematicidal at concentrations of extract in soil above 0.05 g/kg, equivalent to formulation in soil of 0.17 g/kg (Table 1); at this concentration it also reduced tomato shoot weight. In further experiments, Azatin at neem extract concentrations of 0.025 or 0.05 g/kg exhibited very little or no nematicidal activity. Ammonium sulfate at an N concentration of 75 mg/kg increased tomato shoot weight, but did not reduce galling. When the neem extract was applied at a concentration of 0.025 g/kg or higher together with AS, the GI was reduced. There was a significant interaction between Azatin and AS in their effects on galling, but the reduction in the number of nematode eggs per plant was not enhanced by combining AS and the neem extract as compared with the application of the neem extract alone.

Table 1.

Effects of ammonium sulfate (AS) in combination with a neem extract (Azatin) incorporated in soil inoculated with Meloidogyne javanica juveniles on fresh shoot weight (FSW) and galling index (GI) of tomato plants and on number of eggs per plant, 6 wk after planting.

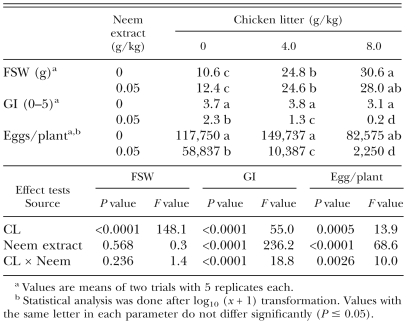

In the experiment with chicken litter, the shoot weight of tomato plants was increased by the application of chicken litter (Table 2). A slight reduction in GI resulted from application of the neem extract at 0.05 g/kg, but chicken litter was not effective in reducing the index even at 8.0 g/kg. Combinations of chicken litter and Azatin reduced the GI more effectively. The number of nematode eggs was reduced by neem extract and/or chicken litter, and there was a significant interaction between chicken litter and neem extract in their effects on GI and numbers of nematode eggs.

Table 2.

Effects of chicken litter (CL) in combination with a neem extract (Azatin) incorporated in soil inoculated with Meloidogyne javanica juveniles on fresh shoot weight (FSW) and galling index (GI) of tomato seedlings and on number of eggs per plant, 6 wk after planting.

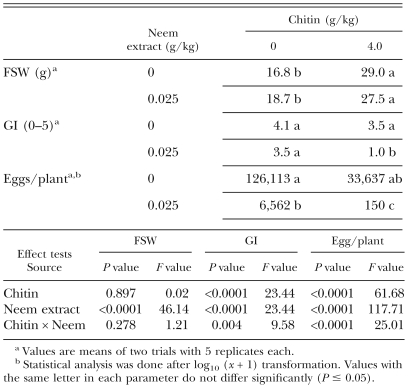

In the experiment with the chitin, tomato plants grown in the soil treated with chitin had larger shoot weights than the control plants or those grown in the soil treated with Azatin (Table 3). The combination of chitin and neem extract reduced GI, whereas application of either of them alone had no effect on GI. Chitin, neem extract and their combination also reduced the number of nematode eggs. There was a significant interaction of chitin and the neem extract in their effects on GI and number of nematode eggs.

Table 3.

Effects of chitin in combination with a neem extract (Azatin) incorporated in soil inoculated with Meloidogyne javanica juveniles on fresh shoot weight (FSW) and galling index (GI) of tomato seedlings and on number of eggs per plant, 6 wk after planting.

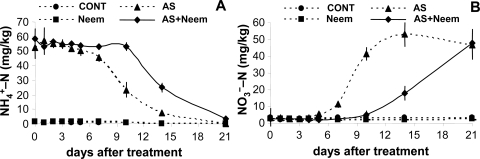

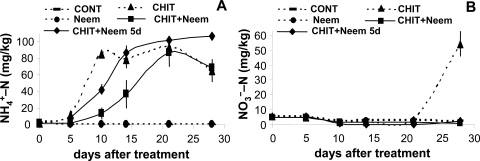

Effect of neem extract on nitrification: The ammonium released from AS underwent nitrification, and the concentration of water-extractable ammonium-N decreased to about 50% of its initial value 10 d after the addition of AS alone to the soil (Fig. 1 A). In the soil treated with AS in combination with neem extract, a similar reduction of the ammonium-N concentration did not occur until 14 d after treatment. After 21 d, the ammonium-N concentrations in both treatments had fallen almost to zero. In both treatments nitrate concentrations increased as ammonium concentrations decreased, although the nitrate concentration in the soil treated with AS plus neem extract started increasing later than that in the soil treated with AS alone (Fig. IB). After 21 d, the nitrate-N concentrations in both the treatments were approximately 45 mg/kg. The soil pH varied between 8.5 and 9.2, but no difference in pH was found between the two treatments.

Fig 1.

Concentrations of ammonium- (A) and nitrate- (B) nitrogen in untreated control soil (CONT) and in soils treated with ammonium sulfate (AS: N at 75 mg/kg), Azatin neem extract (Neem: 0.025 g/kg), and their combination (AS + Neem). Values are means and standard deviation of two trials with four replicates each.

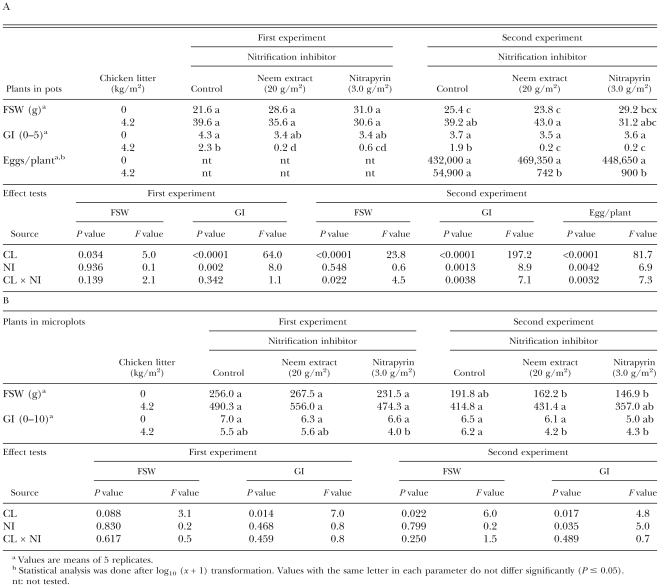

In the soil treated with chitin, the ammonium concentration began to increase 5 d after treatment, reached the maximum concentration (85 mg N/kg) on d 10, and started to decrease after 21 d (Fig. 2A). The increase in ammonium in the soil treated on d 0 with chitin plus the neem extract began later and proceeded more slowly; maximum concentration (87 mg N/kg) was recorded on d 21. In the soil treated with chitin on d 0 and neem extract applied on d 5, the increase in ammonium was slower than that in the soil treated with chitin alone between d 5 and 10, but it did not decrease even by d 28 when the maximum concentration (107 mg N/kg) was recorded. A significant increase in soil nitrate concentration was found only on d 28 in the soil treated with chitin alone (Fig. 2B). No significant difference in soil pH, which varied between 8.6 and 9.3, was found between treatments.

Fig. 2.

Concentrations of ammonium- (A) and nitrate- (B) nitrogen in untreated control soil (CONT) and in soils treated with chitin (CHIT: 4 g/kg), Azatin neem extract (Neem: 0.025 g/kg), and their combination (CHIT + Neem), and Azatin neem extract applied 5 d after chitin treatment (CHIT + Neem 5d). Values are means and standard deviation of two trials with four replicates each.

Field microplot experiment: The fresh shoot weight of tomato plants grown in pots filled with the soil taken from the microplots after treatment was significantly increased by chicken litter in the second trial (Table 4A). The GI of plants in pots was reduced by treatment with chicken litter, but the reduction was greater when the neem extract or nitrapyrin was applied with the chicken litter in both the trials. The number of nematode eggs in the second trial was also reduced by chicken litter, but the reduction was greater by combinations of chicken litter with neem extract or nitrapyrin. In the second trial, there was a significant interaction between the effects of chicken litter and neem extract or nitrapyrin on GI of plants and number of nematode eggs.

Table 4.

Effects of chicken litter (CL) in combination with a neem extract (Easydor) or nitrapyrin as nitrification inhibitor (NI), incorporated into Meloidogyne javanica-infested field microplot, on fresh shoot weight (FSW) and galling index (GI) of and on the number of nematode eggs on tomato plants grown in pots filled with microplots soil after treatment (A) and in treated microplots (B). FSW and GI of plants grown in pots and FSW, GI and number of nematode eggs per plant of those grown in microplots were recorded 6 wk and 2 mon after planting, respectively.

The fresh shoot weight of the tomato plants grown in the field microplots was increased by chicken litter only in the second trial (Table 4B). In both trials, the application of chicken litter, neem extract or nitrapyrin alone did not affect the GI, which was reduced only by the combination of chicken litter with nitrapyrin in the first trial, and by the combinations of chicken litter with the neem extract or nitrapyrin in the second trial. No significant interaction between the main effects on GI of plants grown in the microplots was found in either of the trials.

Discussion

Ammonium hydroxide was previously found to be an effective nematicide at N doses greater than 500 kg/ha on an alkaline sandy soil in Israel (Oka and Pivonia, 2002). Organic amendments, especially those with low C:N ratios that release ammonia as they decompose in the soil, have also been found effective in controlling nematodes (Rodríguez-Kábana et al., 1987; Oka et al., 1993). In this study, the possibility of reducing the doses of ammonia-releasing amendments needed for nematode control was tested by combining them with neem extracts, which are known as nematicides and nitrification inhibitors and which can be used in organic farming systems. Concentrations of neem extracts that did not reduce nematode galling on tomato, or did so only slightly, were used in experiments to enhance the nematicidal activity of ammonia-releasing amendments. The neem extract applied alone often reduced the number of nematode eggs per plant, although GI was not affected. The concentrations tested in this study would retard nematode infection, probably through a reversible nematostatic effect, and subsequent nematode development and egg production would also be retarded.

In most of the growth chamber experiments, GI were greatly reduced when ammonia-releasing amendments were combined with the neem extracts. This enhancement of nematicidal activity was hypothesized to be caused by extended exposure to ammonia. In fact, the soil analysis showed that the neem extract inhibited the nitrification of the ammonium and/or ammonia released from AS and chitin and maintained the concentrations for longer periods. In field microplot experiments, nitrapyrin, a chemical nitrification inhibitor, had a very similar effect on the GI to that of neem extract. The neem extracts contained limonoid azadirachtin, which is known as a pesticide at 3%, and other compounds derived from the plant. We do not know whether the nitrification was inhibited by the azadirachtin or by other compounds in the extracts. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no published reports of nitrification inhibition by azadirachtin. However, triterpenes from neem seeds were suggested to be responsible for nitrification inhibition.

Another possible mechanism for the reduction in nematode damage by the addition of the neem extract may have been due to the difference in the nitrogen forms available for plant nutrition. Increased nitrate concentrations in the soils treated with AS or chitin in combination with the neem extract occurred more slowly than those in soils treated with either of them alone. Nitrification was completely inhibited in soils treated with chitin and the neem extract up to day 28. The presence of different forms of nitrogen in fertilizers has been reported to have differing effects on nematode suppression; fertilizing plants with NH4–N, at 448 to 896 ppm, instead of NO3–N reduced nematode damage to soybean by Heterodera glycines and to bean by M. incognita (Oteifa, 1955; Barker et al., 1971). Incidence and severity of plant diseases were influenced by the form of nitrogen used in fertilizers (Huber and Watson, 1974). For example, addition of nitrapyrin reduced the incidence of take-all on wheat, probably by preserving the NH4 +–N form which is toxic to the fungus (Smiley and Cook, 1973).

The use of nitrification inhibitors in combination with ammonium compounds or organic amendments does not always enhance the control efficacy of soil-borne diseases. Fungicidal activity of nitrogen-rich organic amendments against Verticillium dahliae was reduced by treatment with dicyandiamide, another nitrification inhibitor (Lazarovits et al., 2000). The reduction in efficacy was attributed to the absence of nitrous acid (HNO2) in the soil, which occasionally accumulates in ammonia-treated soils after nitrification. The fungicidal and nematicidal effects of ammonia-releasing organic amendments in acid soils may be partly caused by nitrous acid accumulation following ammonia release and its nitrification to nitrite. Nitrous acid is known to be fungicidal and nematicidal in acidic soils (Walker, 1971; Tsao and Oster, 1981; Oka et al., 1993; Tenuta and Lazarovits, 2002). In the present study, involvement of nitrous acid in the nematicidal activity of amendments can be neglected because of the high soil pH and better nematicidal activity with nitrification inhibitors.

In our preliminary experiments, the application of chitin with neem extract at the same time (d 0) caused no effect or increased the GI of tomato (unpublished data). In the present study, neem extract was applied five days after the incorporation of chitin into soil. In this case, root GI was reduced. The soil analysis in the present study showed that the release of ammonia from chitin, through mineralization of organic nitrogen by microorganisms in the soil, was inhibited by the neem extract applied at day 0. Neem extracts are known to have antimicrobial activity (Coventry and Allan, 2001; Alzoreky and Nakahara, 2003). This inhibition of the mineralization by the neem extract was hypothesized to be the cause of the "non-enhancement" of the nematicidal activity of the chitin applied with the neem extract on the same day in the preliminary experiments (unpublished data). Neem extracts should be added to the soil as nitrification inhibitors when the ammonium concentration in the soil has maximized following the application of ammonia-releasing amendments. In contrast, Gnanavelrajah and Kumaragamae (1998) found that general microbial activity was not impaired by neem treatments and concluded that application of neem cake or extract did not hinder normal microbial activity; each bioactive compound in the extracts would be effective against a specific range of organisms. In another study, neem seed extracts demonstrated anti-fungal and antibacterial activity, but azadirachtin, nimbin and salannin were found not to be antibacterial compounds (Coventry and Allan, 2001). The inhibition of microbial activity by the neem extracts would also affect the activity of microbes antagonistic to nematodes, and such microbial activity has been reported to be also involved in the nematicidal activity of organic amendments (Spiegel et al., 1987; Kaplan et al., 1992). Nitrapyrin, which probably acts on the cytochrome oxi-dase of Nitrosomonas and not on the nitrite oxidizing system of Nitrobacter, was shown to inhibit the growth of the bacteria (Campbell and Aleem, 1965a, 1965b). However, microbial activity in the soil may recover after degradation of the inhibitors, which is affected by soil environmental factors, such as pH, temperature and organic matter.

Although the effect of neem extract in combination with amendments on reduction of GI of tomato was very pronounced in the pot experiments, the extract caused little or no enhancement of GI reduction by chicken litter in the field microplot experiments. The treatment did not seem to affect nematode J2 located deeper in the soil, and these survived to become nematodes that infected the plants later. In fact, in both field microplots trials, tomato plants grown in pots filled with soils that had been treated with chicken litter and neem extract or nitrapyrin in the microplots had much lower GI than plants grown in the soils of the control plots or of plots treated with chicken litter, neem extract or nitrapyrin alone. Thus, delivery of soil amendments more deeply into the soil is one of the main problems in the application of nematode suppressive amendments.

The results of the present study suggest that the use of ammonia-releasing amendments in combination with neem extracts or other nitrification inhibitors could make nematode control more practicable by reducing the amount of amendments needed. This control method should be tested in other soil types, because only dune sand and sandy soil were used in the present study and organic amendments were more effective in root-knot nematode control in a sandy soil than in soils containing higher percentages of silt and organic matter (Oka et al., 2007). In light of the high costs of commercial neem extract formulations, which are used mainly against insect pests in far smaller quantities per unit area than would be required for nematode control, it might be economically feasible to use crude neem materials, such as neem oilcake, if they were shown to have a similar effect.

Footnotes

This paper was edited by Brian Kerry.

Literature Cited

- Alzoreky NS, Nakahara K. Antibacterial activity of extracts from some edible plants commonly consumed in Asia. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2003;80:223–230. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(02)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker KR. Nematode extraction and bioassays. An advanced treatise on Meloidogyne, vol. II, Methodology. In: Barker KR, Carter CC, Sasser JN, editors. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State University Graphics; 1985. pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Barker K, Lehman PS, Huisingh D. Influence of nitrogen and Rhizobium japonicum on the activity of Heterodera glycines. Nematologica. 1971;17:377–385. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge J, Page SLJ. Estimation of root-knot nematode infestation levels on roots using a rating chart. Tropical Pest Management. 1980;26:296–298. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell NER, Aleem MIH. The effect of 2-chloro, 6-(trichloromethyl) pyridine on the chemoautotrophic metabolism of nitrifying bacteria. I. Ammonia and hydroxylamine oxidation by Nitrosomonas . Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1965a;31:124–136. doi: 10.1007/BF02045882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell NER, Aleem MIH. The effect of 2-chloro, 6-(trichloromethyl) pyridine on the chemoautotrophic metabolism of nitrifying bacteria. II. Nitrite oxidation by Nitrobacter . Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1965b;31:137–144. doi: 10.1007/BF02045883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coventry E, Allan EJ. Microbiological and chemical analysis of neem (Azadirachta indica) extracts: New data on antimicrobial activity. Phytoparasitica. 2001;29:441–450. [Google Scholar]

- Duplessis MCF, Kroontje W. The relationship between pH and ammonia equilibria in soil. Proceedings of the Soil Science Society of America. 1964;28:751–754. [Google Scholar]

- Eno CF, Blue WG, Good JM., Jr The effect of anhydrous ammonia on nematodes, fungi, bacteria, and nitrification in some Florida soils. Proceedings of the Soil Science Society of America. 1955;19:55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Focht DD, Verstrate W. Biochemical ecology of nitrification and denitrification. Advances in Microbial Ecology. 1977;1:135–214. [Google Scholar]

- Gnanavelrajah N, Kumaragamae D. Effect of neem (Azadirachta indica A. Juss) materials on nitrification of applied urea in three selected soils of Sri Lanka. Tropical Agricultural Research. 1998;10:61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gnanavelrajah N, Kumaragamae D. Nitrogen leaching losses and plant response to nitrogen fertilizers as influenced by application of Neem (Azadirachta indica A. Juss) materials. Tropical Agricultural Research. 1999;11:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Goring CIA. Control of nitrification by 2-chloro-6-(trichloromethyl) pyridine. Soil Science. 1962;93:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Huber DM, Watson RD. Nitrogen form and plant disease. Annual Review of Phytopathology. 1974;12:139–165. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.12.090174.001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey RS, Barker KR. A comparison of methods of collecting inocula of Meloidogyne spp., including a new technique. Plant Disease Reporter. 1973;57:1025–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan M, Noe JP, Hartel PG. The role of microbes associated with chicken litter in the suppression of Meloidogyne arenaria . Journal of Nematology. 1992;24:522–527. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarovits G, Tenuta M, Conn KL. Utilization of high nitrogen and swine manure amendments for control of soil-borne diseases: Efficacy and mode of action. Acta Horticulture. 2000;532:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mojumdar V. Effects on nematodes. The neem tree, Azadirachta indica A. Juss. and other Meliaceous plants: Source of unique natural products for integrated pest management, industry, and other purposes. In: Schmutterer H, editor. Weinheim, Germany: VCH; 1995. pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y, Chet I, Spiegel I. Control of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica by Bacillus cereus . Biocontrol Science and Technology. 1993;3:115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y, Pivonia S. Use of ammonia-releasing compounds for control of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica . Nematology. 2002;4:65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y, Pivonia S. Effect of a nitrification inhibitor on nematicidal activity of organic and inorganic ammonia-releasing compounds against the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica . Nematology. 2003;5:505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y, Shapira N, Fine P. Control of root-knot nematodes in organic farming system by organic amendments and soil solarization. Crop Protection. 2007 (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y, Tkachi N, Shuker S, Rosenberg R, Suriano S, Fine P. Laboratory studies on the enhancement of nematicidal activity of ammonia-releasing fertilizers by alkaline amendments. Nematology. 2006a;8:335–346. [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y, Tkachi N, Shuker S, Rosenberg R, Suriano S, Fine P. Field studies on the enhancement of nematicidal activity of ammonia-releasing fertilisers by alkaline amendments. Nematology. 2006b;8:881–893. [Google Scholar]

- Oteifa BA. Nitrogen source of the host nutrition in relation to infection by a root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita . Plant Disease Reporter. 1955;39:902–903. [Google Scholar]

- Raguraman S, Ganapathy N, Venkatesan T. Neem versus entomopathogens and natural enemies of crop pests: The potential impact and strategies. In: Koul O, Wahab S, editors. Neem: Today and in the new millennium. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2004. pp. 125–182. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Kábana R. Organic and inorganic amendments to soil as nematode suppressants. Journal of Nematology. 1986;18:129–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Kábana R, Morgan-Jones G, Chet I. Biological control of nematodes: Soil amendments and microbial antagonists. Plant and Soil. 1987;100:237–247. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Kábana R, Shelby RA, King PS, Pope MH. Combinations of anhydrous ammonia and 1,3-dichloropro-penes for control of root-knot nematodes in soybeans. Nematropica. 1982;12:61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sahrawat KL, Mukerjee SK. Nitrification inhibitors. I. Studies with karanjin, a furanolflavonoid from karanja (Pongamia glagra) seeds. Plant and Soil. 1977;47:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sayre RM, Patrick ZA, Thorpe HJ. Identification of a selective nematicidal component in extracts of plant residues decomposing in soil. Nematologica. 1965;11:263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Smiley RW, Cook RJ. Relationship between take-all of wheat and rhizosphere pH in soils fertilized with ammonium vs. nitrate nitrogen. Phytopathology. 1973;63:882–889. [Google Scholar]

- Smiley RW, Cook RJ, Papendic RI. Anhydrous ammonia as a soil fungicide against Fusarium and fungicidal activity in the ammonia retention zone. Phytopathology. 1970;60:1227–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel Y, Chet I, Cohen E. Use of chitin for controlling plant parasitic nematodes. II. Mode of action. Plant and Soil. 1987;98:337–345. [Google Scholar]

- Stirling GR. Oxon, UK: CAB International; 1991. Biological control of plant parasitic nematodes. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh G, Gopalakrishnan G, Masilamani S. Neem for plant pathogenic fungal control: The outlook in the new millennium. In: Koul O, Wahab S, editors. Neem: Today and in the new millennium. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2004. pp. 183–208. [Google Scholar]

- Swezey AW, Turner GO. Crop experiments on the effect of 2-chloro-6-(trichloromethyl) pyridine for the control of nitrification of ammonium and urea fertilizers. Agronomy Journal. 1962;54:532–535. [Google Scholar]

- Tenuta M, Lazarovits G. Ammonia and nitrous acid from nitrogenous amendments kill the microsclerotia of Verticillium dahliae . Phytopathology. 2002;92:255–264. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2002.92.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao PH, Oster JJ. Relation of ammonia and nitrous acid to suppression of Phytophthora in soils amended with nitrogenous organic substances. Phytopathology. 1981;71:53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Usha K, Patra DD. Medicinal and aromatic plant materials as nitrification inhibitors for augmenting yield and nitrogen uptake of Japanese mint (Mentha arvensis L. var. piperascens) Bioresource Technology. 2003;86:267–276. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(02)00143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JT. Populations of Pratylenchus penetrans relative to decomposing nitrogenous soil amendments. Journal of Nematology. 1971;3:43–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren KS. Ammonia toxicity and pH. Nature. 1962;195:45–49. doi: 10.1038/195047a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]