Abstract

H+-pumping rhodopsins mediate a primordial conversion of light to metabolic energy. Bacteriorhodopsin from Halobacterium salinarium is the first identified and (biochemically) best-studied H+-pumping rhodopsin. The electrical properties of H+-pumping rhodopsins, however, are known in more detail for the homolog Acetabularia rhodopsin, isolated from the eukaryotic green alga Acetabularia acetabulum. Based on data from Acetabularia rhodopsin we present a general reaction kinetic model of H+-pumping rhodopsins with only seven independent parameters, which fits the kinetic properties of photocurrents as functions of light, transmembrane voltage, internal and external pH, and time. The model describes fast photoisomerization of retinal with simultaneous H+ transfer to an H+ acceptor, reprotonation of retinal from the intracellular face via an H+ donor, and proton release to the extracellular space via an H+ release complex. The voltage sensitivities of the individual reaction steps and their temporal changes are treated here by a novel approach, whereby—as in an Ohmic voltage divider—the effective portions of the total transmembrane voltage decrease with the relative velocities of the individual reaction steps. This analysis quantitatively infers dynamic changes of the voltage profile and of the pK values of the H+-binding sites involved.

INTRODUCTION

As for the experimental system, H+-pumping rhodopsins are the key enzymes for a primordial conversion of light into metabolic energy (i.e., photosynthesis). The crucial, light-driven uphill transport of protons is brought about by a single membrane protein (opsin), which forms the functional entity (rhodopsin) by incorporation of a retinal molecule via a retinylidene Schiff base. Bacteriorhodopsin (BR) from the archaea Halobacterium salinarium is the first and biochemically best-investigated rhodopsin (For review, see, e.g., (1)). However, H+-pumping rhodopsins have also been identified in eubacteria (2), and even eukaryotes (3,4). The electrical properties of light-driven H+-pumping by rhodopsins were investigated in the past in living cells attached to black-lipid membranes (5–8), in anisotropically suspended rhodopsins in acrylamide gels, in solid supported membranes (9), and in rhodopsins heterologically expressed in oocytes of Xenopus laevis (10) or HEK293 cells (11). Steady-state current-voltage relationships could, however, only be recorded in oocytes or HEK293 cells where the rhodopsins are all incorporated with correct orientation and the transmembrane voltage is controlled by the experimenter.

Recently, Tsunoda et al. (3) characterized the light-mediated electrical properties of Acetabularia rhodopsin (AR), a rhodopsin from the green alga Acetabularia, heterologically expressed in Xenopus oocytes. The aim of this study is to understand these properties on a quantitative, physicochemical level by comparing the experimental data with theoretical expectations from appropriate reaction kinetic models. Since the electrical description of AR is more detailed than that of the biochemically and spectroscopically better-investigated bacteriorhodopsin (BR), a discrete model for AR is considered relevant for all H+ pumping rhodopsins, including BR, of course. The analysis presented here is based on data from a previous study (3). Different methods are available to predict current flow through a transport molecule from the molecular structure of the transport protein. They provide different pros and cons with respect to modeling protein dynamics and description of measured data, whereas MD studies of channels and pumps focus on individual transporter molecules, recordings of whole-cell currents reflect the statistical mean of a larger number of transporters in vivo. To obtain physiologically relevant statements for transmembrane currents from MD, it is necessary, therefore, to calculate means of a larger number of trajectories which is unrealistic at presently available computation facilities, at least in our case of H+ pumping rhodopsins, where slow relaxations cause additional complications (12). Thus, substantial simplifications are necessary to obtain some macroscopic results from MD. In Brownian dynamics simulations and Poisson-Nernst-Plank approaches a rigid structure of the protein is assumed, and the water molecules are replaced by a continuum (13–15).

In both theories the driving force of an ion i can be described by the Langevin equation midv = −mifivi + Fr + qiU, where mi, qi, vi, and fi are the mass, charge, velocity, and frictional coefficients of the transported species at forces from random collision Fr and a given electric field strength U. To calculate U, Poisson-Nernst-Plank uses the additional simplification that the distribution of ions in the system can be approximated by a continuous charge distribution (13). MD and Brownian dynamics calculations face the problem of accurately determining the (fluctuating) field strength within the channel and great effort has been invested to integrate dielectric and mechanical properties into the calculations (14–21). But even if the electric field within the channel were known, it is difficult to get averaged currents from the individual charge trajectories. Another continuum theory that avoids these difficulties is the Nernst-Planck equation which, in our case of H+ movement, corresponds to Mitchell's concept of proton-motive force (22,23). In fact, structural analysis has revealed proton wells in redox- and light-driven transporters mediating energy conversion (23). The Nernst-Plank approach does not account for noise; instead, it combines Ohm's law for electromigration with Fick's law of diffusion (15,16). If detailed knowledge of the protein structure is not available, these microscopic approaches have to be replaced by macroscopic ones with the assumption that the ions are preferentially localized in specific sites of the pathway and that transitions between these sites determine the kinetics of the global transport process (13). These transitions comprise not only changes of H+ from one site to an immediately adjacent one, but also migration of H+ along proton wires (24), including stretches of water networks (25) which are essential not only in energy conversion but also in voltage gating of ion channels by motion of the S4 helix (26–28) and in cotransporters (29,30). To satisfy microscopic and macroscopic aspects of H+ pumping by rhodopsin, Ferreira and Bashford (31) used an intermediate approach, defining 25 microstates that are linked by conformation changes and proton transfer steps, as determined from molecular dynamic calculations. Here we reduce the structural information even more, namely to an extent that allows a one-to-one assignment to the electrophysiological data available.

The initial aim of this study was an enzyme kinetic analysis of light-induced electrical currents I in H+ pumping rhodopsins. When conventional reaction kinetic attempts failed, a surprisingly simple modification resulted in a good description of the experimental data. This modification is based on the idea that—like in an Ohmic voltage divider—for each reaction step i, the individual portion di = Ei/E of the total voltage,  decreases with the particular electrical conductance of this step, which, in turn, increases with the rate constants ki involved. This approach infers considerable temporal changes of the voltage profile within the charge-translocating enzyme upon changes of the conditions, especially of the light intensity. To our knowledge, it is a novel approach to determine d from k, in enzyme kinetics of voltage-dependent transporter proteins.

decreases with the particular electrical conductance of this step, which, in turn, increases with the rate constants ki involved. This approach infers considerable temporal changes of the voltage profile within the charge-translocating enzyme upon changes of the conditions, especially of the light intensity. To our knowledge, it is a novel approach to determine d from k, in enzyme kinetics of voltage-dependent transporter proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental data

The experimental data used here are representative examples from a previous study (3), where statistical support of these data is given.

Model

We adopt the established description of the transport process by a series of transitions of H+ from one binding site to another (1,32–36). Spectroscopic and crystallographic studies show that the photocycle of BR comprises several small steps of H+ translocation that add up to a movement of one H+ through the entire membrane. These reactions, which are the consequences of changes in H+ affinity of the individual H+-binding sites, are summarized in Eq. 1, where the main line marks the individual states and reactions. The top line marks the spectroscopic transitions according to the traditional nomenclature, and the bottom line marks the temporal order of the individual steps from Balashov et al. (37):

|

(1) |

This scheme reflects the sequence of spectroscopically identified intermediates of the photochemical reaction cycle of BR. It starts with a photoisomerization (BR → L) of the Schiff base S and a simultaneous transfer of its proton to the acceptor aspartate, A. The next step (L → M) corresponds to the release of an H+ from the proton release complex, C, to the external medium. The following transition (M → N) reflects the H+ transfer from the donor aspartate, D, to the Schiff base, S. The cycle ends with the spectroscopically identified transitions N → O and O → BR, which reflect the reprotonation of D from the cytoplasmic medium, and the H+ transfer from the acceptor, A, to the proton release complex, C, respectively. Interestingly, as the behavior of the pump is controlled by transient pK changes (38), the temporal order of these reaction steps differs from their spatial order from inside to outside.

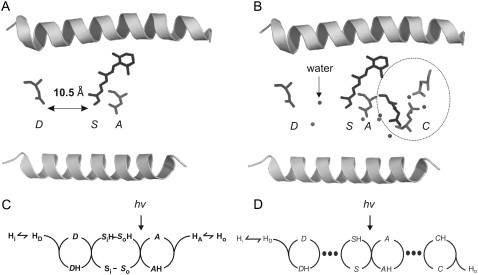

We consider a population of rhodopsin molecules. In this macroscopic view, means of discontinuous molecular events result in apparent continuous functions; e.g., transition probabilities appear as rate constants and mixtures of discrete states as intermediates. Fig. 1 compares some structural features (Fig. 1, A and B) and a reaction scheme (Fig. 1, C and D) of H+ pumping rhodopsins according to the literature (33,39); see also Eq. 1. The left panels (Fig. 1, A and C) represent the state of a previous study on AR (3), and the right panels (Fig. 1, B and D) show basically the same features, but with the following updates: The Schiff base, S, is not represented by four states (namely So, Si, SiH, and SoH in Fig. 1 C), discriminating between orientation toward cytoplasmic and lumenal side (Fig. 1 C), but by two states only (S, SH; Fig. 1 D), a protonated (resting) state and a deprotonated state. This simplification is justified because vectorial transport can take place without switching accessibility (31,40). Furthermore, the two proton transfer steps from the Donor, D, to S and from the acceptor, A, to the H+ release complex, C, which has not been considered before, are assumed to be limited by electrodiffusion of H+ through water network stretches of ∼10 Å distance within the H+ conducting pore, marked by large dots in Fig. 1 D. The proton release complex, C, is represented in Fig. 1 B by three encircled amino acids (41).

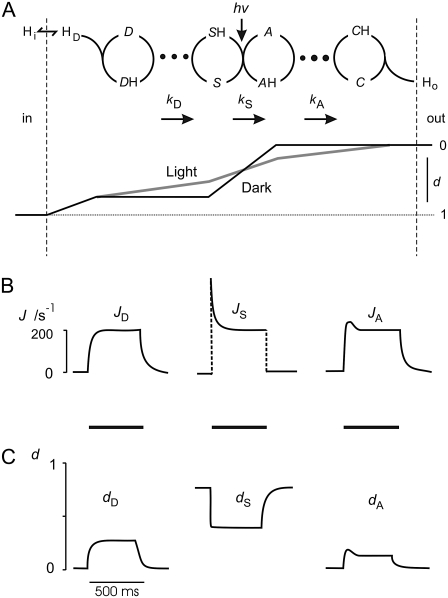

FIGURE 1.

Structural (top) and kinetic (bottom) minimum model for H+ pumping rhodopsins; left panels (A and C): preceding three-cycles model in Tsunoda et al. (3), with slightly modified nomenclature; right panels (B and D): present four-cycles model, extended by stretches of electrodiffusion of H+ through water (dots), and the known proton release complex C (35). Symbols: Two schematic helices mark pore, i, inside (cytoplasmic space); o, outside (luminal space); D, proton-donor amino acid in inner half-pore (D96 in BR and D100 in AR); S, Schiff base of photoisomerizing retinal, if indexed; i,o, access of proton binding site to D, A, respectively; A, proton-acceptor amino acid in outer half-pore (D85 in BR and D91 in AR); C, proton release complex; Y57, R82, Y83, D85, D96, E204 and D212 in BR, and Y60, R86, Y87, D89, D100, E206, and D214 in AR; H, H+. Double-headed arrows mark fast H+ equilibria.

Common entities of the previous model and the model presented here are a voltage-sensitive proton equilibrium between the cytoplasmic bulk phase (Hi) and at the binding site (HD) of the donor, and protonated/deprotonated states D, S, A of the series of H+ transfer sites. The rate equations related to the individual steps in Eq. 1 are as follows:

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

Equation 2 defines the fast equilibria of protonation on the entrance side, i.e.,  Equation 6 reflects a more complex situation. The proton-release complex consists of at least three amino acids in BR and is not identified in detail in AR. However, the kinetic effect of pHo in AR can be accounted for by two different proton acceptors with pKo1 and pKo2. Equation 6 represents the averaged protonation of two equilibria, which is

Equation 6 reflects a more complex situation. The proton-release complex consists of at least three amino acids in BR and is not identified in detail in AR. However, the kinetic effect of pHo in AR can be accounted for by two different proton acceptors with pKo1 and pKo2. Equation 6 represents the averaged protonation of two equilibria, which is  Since the relationships between D and DH as well as those of C and CH are fixed by the pH- and pK-values for the respective fast equilibria, and since the small transport steps through both water cavities (Eqs. 3 and 5) are merged into only two equations, the system of the Eqs. 2–6 consists of only the two pairs of variables S/SH and A/AH. If the net fluxes of the respective reactions 3–5 were denoted as

Since the relationships between D and DH as well as those of C and CH are fixed by the pH- and pK-values for the respective fast equilibria, and since the small transport steps through both water cavities (Eqs. 3 and 5) are merged into only two equations, the system of the Eqs. 2–6 consists of only the two pairs of variables S/SH and A/AH. If the net fluxes of the respective reactions 3–5 were denoted as  and

and  then the following differential equations describe the changes of the occupation probabilities PS and PA of the protonated states SH and AH,

then the following differential equations describe the changes of the occupation probabilities PS and PA of the protonated states SH and AH,

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

with

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

where kS in Eq. 10 is proportional to the light intensity (see Table 1). Each step of the reaction scheme of Fig. 1 D comprises the unidirectional flux Ji = Ji→i+1 of H+ from one position, i, to the next, i + 1, through a certain portion of the membrane. In a generalized form, Eqs. 9–11 can be written as

|

(12) |

where i = D, S, or A; Pi is the probability to find a binding site in its protonated form; (1 – Pi) is the probability of a site to be deprotonated; and ki = ki,i+1 and k–i = ki+1,i are the rate constants for the forward and backward transitions.

TABLE 1.

Critical parameters for electrokinetic properties of H+-pumping rhodopsin; definitions in Fig. 1 D and Eqs. 2–6

| Symbol | Meaning | Unit | Value | Eqs. | Fig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pKi | Equilibrium  donor. donor. |

7.1 | 2 | 5 | |

| pKo1 | 1. Equilibrium  release complex. release complex. |

3.6 | 6 | 5 | |

| pKo2 | 2. Equilibrium  release complex. release complex. |

10 | 6 | 5 | |

|

Electrodiffusion D ↔ S at E = 0. | s−1 | 39 | 3,14 | 3,4,5 |

|

Photoisomerizing S → A at E = 0; 100% light. | s−1 | ≥220 | 4,13 | 3,4,5 |

|

Electrodiffusion A ↔ C at E = 0. | s−1 | 65 | 5,14 | 3,4,5 |

| dHi | Fraction in HD = Hi × exp(dHiu). | 0.24 | 1,6 |

According to rate theory (42), the portion di of the total, reduced transmembrane voltage u = eE/kT will affect the transition probabilities by the relationships

|

(13) |

where the superscript 0 marks the k value at zero voltage, and the factor 1/2 in the exponents reflect the assumption of a symmetric barrier. For small values of di u (linearity) and for  Eq. 13 degenerates to

Eq. 13 degenerates to

|

(14) |

Here we use  because electromigration through the water network is assumed symmetric and rate-limiting compared to the fast binding and debinding reactions to and from the corresponding acceptors and donors. Voltage-sensitivities enter Eqs. 9 and 11 by the linear relationships of Eq. 14 for the electromigration of H+ through a water network. In contrast, the voltage-sensitivity of the direct H+ transfer from SH to AH by kS (Eq. 4) turned out to be better described by the nonlinear formalism of Eq. 13 for an Eyring barrier. In principle, the description of voltage-dependent transition ki requires two parameters, the height,

because electromigration through the water network is assumed symmetric and rate-limiting compared to the fast binding and debinding reactions to and from the corresponding acceptors and donors. Voltage-sensitivities enter Eqs. 9 and 11 by the linear relationships of Eq. 14 for the electromigration of H+ through a water network. In contrast, the voltage-sensitivity of the direct H+ transfer from SH to AH by kS (Eq. 4) turned out to be better described by the nonlinear formalism of Eq. 13 for an Eyring barrier. In principle, the description of voltage-dependent transition ki requires two parameters, the height,  and the relative width, di, of the barriers within the total voltage profile. However, in an Ohmic sense, these two parameters are not independent, because the partial voltage drop di E across the resistor Ri = 1/Gi (Gi = conductance) of a series of resistors with a total resistance R will be determined by di = Ri/R, where the velocity

and the relative width, di, of the barriers within the total voltage profile. However, in an Ohmic sense, these two parameters are not independent, because the partial voltage drop di E across the resistor Ri = 1/Gi (Gi = conductance) of a series of resistors with a total resistance R will be determined by di = Ri/R, where the velocity  may be considered proportional to 1/Ri. So a relationship

may be considered proportional to 1/Ri. So a relationship  di = const might be stated, which would mean that the shape of a barrier is conserved, because lowering its height,

di = const might be stated, which would mean that the shape of a barrier is conserved, because lowering its height,  will cause a concomitant narrowing of its width, di. In our case, the situation is more complicated, because the conductance equivalent Gi of a reaction step is not only determined by the reference rate constants,

will cause a concomitant narrowing of its width, di. In our case, the situation is more complicated, because the conductance equivalent Gi of a reaction step is not only determined by the reference rate constants,  but by the actual rate constants ki, and the occupancies Pi involved. The local current related to charge movement between sites i and i + 1 is

but by the actual rate constants ki, and the occupancies Pi involved. The local current related to charge movement between sites i and i + 1 is

|

(15) |

The slope conductivity (Gi = d(Ii)/d(Ei)) related to the individual reaction steps can be calculated from Eqs. 12 and 15,

|

(16) |

where not only the transition probabilities k are important but also the occupancies of the states which can deliver and receive a H+. With Ei = Gi Ii being the fraction of the electrical potential dropping between site i and site i + 1,

|

(17) |

The Ramo-Shockley theorem (43) states that each process comprising a movement of charge ze within a membrane by the (electric) distance di perpendicular to its surface will create corresponding changes of the image charges at the membrane surfaces, which will be recorded under voltage-clamp conditions as the unidirectional current

|

(18) |

The kinetic model used here consists of the five reactions in Eqs. 2–6. To reduce the number of independent system parameters to a minimum, the following simplifications are used:

Simplification 1

Reactions 2 and 6 are considered to be fast equilibria which are described by three pK values, one (pKi) for reaction 2 and two (pKo1 and pKo2) for reaction 6. The second equilibrium, pKo2 was introduced to satisfy the striking conductance increase at very alkaline pHo (3). Since a conductance G cannot be calculated from pK values, the fraction dHi for reaction 2 was calculated from  We used this value both for light and dark reactions. A corresponding fraction dHo > 0 for reaction 6 did not improve the fits. Therefore, dHo could be ignored which resulted in the four parameters pKi, pKo1, pKo2, and dHi for the description of these equilibria.

We used this value both for light and dark reactions. A corresponding fraction dHo > 0 for reaction 6 did not improve the fits. Therefore, dHo could be ignored which resulted in the four parameters pKi, pKo1, pKo2, and dHi for the description of these equilibria.

Simplification 2

The light-dependent reaction kS (reaction 4) can be assumed to be irreversible, i.e., the rate constant k–S for the back-reaction is zero (the blue-light induced exception presented in reaction 3 is not treated here). Since the relative velocity of the forward reaction kS (compared to the dark reactions kA and kD) determines also the electrical distance dS by Eqs. 16 and 17, reaction 4 is determined by one parameter only kS, which also represents the light-sensitivity of the system.

Simplification 3

Reactions 3 and 5 describe the migration of a proton through a water network with the linear voltage-dependencies of Eq. 14. This linear approach corresponds to a series of transitions across barriers of similar height. Since the rate constants for forward- and back-reaction can be assumed to be the same at zero voltage, only one system parameter is required for each of these two reactions ( and

and  ) and the fractions, dA and dD, are determined again by Eqs. 16 and 17. So these two reactions for electromigration are determined by two additional system parameters altogether.

) and the fractions, dA and dD, are determined again by Eqs. 16 and 17. So these two reactions for electromigration are determined by two additional system parameters altogether.

Summarizing, the entire system can be described by seven system parameters. A scaling factor may be required as an eighth parameter, which accounts for the particular expression level (number of operating rhodopsin molecules) in the oocyte used. This number is in the range of 1010 per oocyte (3) and cancels out when experimental data from different oocytes are normalized. An example of this estimate can be obtained by comparing the experimental steady-state photocurrents of ∼2 × 10−7A from an oocyte in Fig. 2 with the microscopic steady-state currents of an individual rhodopsin in Fig. 4 of ∼200 e s−1 ≈ 3.2 × 10−17A with e ≈ 1.6 × 10−19A s.

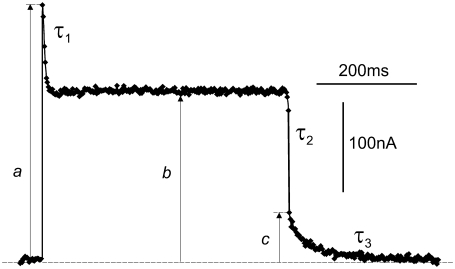

FIGURE 2.

Typical time course of photocurrent upon a rectangular light pulse, mediated by a H+ pumping rhodopsin expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Characteristic, observable parameters are the amplitudes: a, initial, fast response; b, steady-state level; and c, initial current after downstep at end of light pulse. Time constants: τ1 for exponential relaxation from a to b; and τ3 for exponential relaxation from c to baseline, i.e., dashed control (zero) current in absence of light. Fast changes by τ0 (from baseline to a, not marked) and τ2 (from b to c) are not resolved (data from (3)).

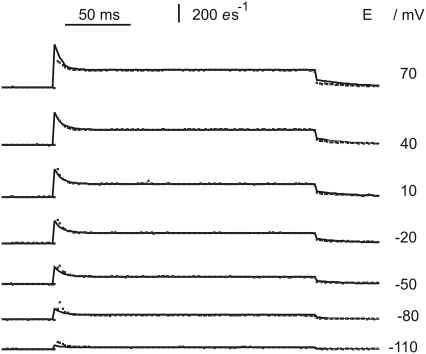

FIGURE 4.

Examples of photocurrents upon pulses of green 532 nm light (50 ms bars), recorded at different holding voltages as marked. The points (light tracings) are measured and the black curves are fitted by the model described. In Fig. 1 D and Eqs. 5–18 with parameters listed in Table 1. Currents I are expressed as elementary charges e per second through one rhodopsin molecule.

Numerical methods

The electrical behavior is described by means of Eq. 18 with di from Eq. 17, and Ii from Eq. 15. The meanings of ki, Gi, and Ji are defined by Eqs. 9–11, 13, and 16. Calculating the electrical distances, di, by Eq. 17 requires the knowledge of Gi and the rate constants ki(di). Therefore, preliminary ki values were calculated from estimated di values first. Using these start values, the values of di and ki were then improved iteratively.

Custom-tailored software was written in C# and is available on request. Model calculations were performed by application of a conventional Runge-Kutta algorithm to Eqs. 7 and 8 and calculation of the least-square error to all data of Figs. 3–5, simultaneously. For fits, the error was minimized by direct search calculations under variation of the model parameters by small steps <1% per iteration, according to Hookes and Jeeves (44). Suitable start parameters were chosen by trial and error.

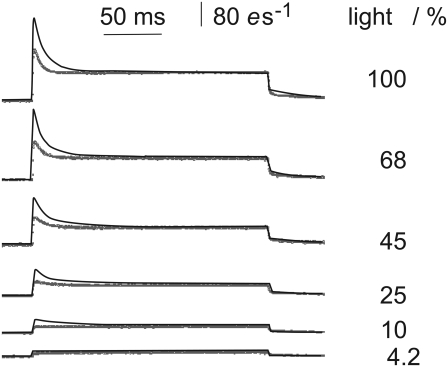

FIGURE 3.

Fit to time courses of photocurrents upon square-waved light pulses of different intensity. Currents I are expressed as elementary charges e per second through one rhodopsin molecule. (Light tracing) Measured data. (Dark tracing) Data fitted by the reaction scheme in Fig. 1 D with parameters listed in Table 1. Light intensities as indicated, 100% ≈1021 photons (532 nm) m−2 s−1; conditions, pHi = 7.3, pHo = 7.3, and E = 60 mV.

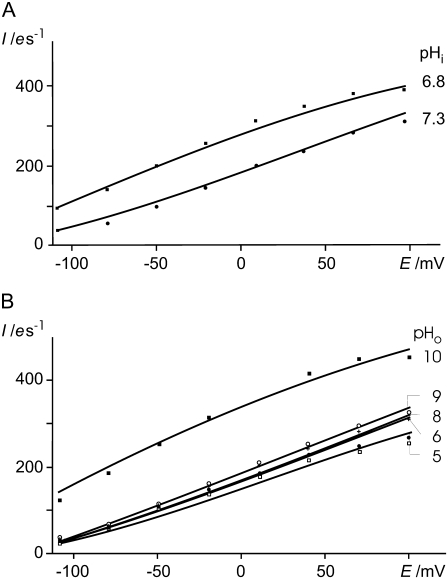

FIGURE 5.

(A) Sensitivity of steady-state photocurrent (100% light) to transmembrane voltage, E, and to cytoplasmic [H+]i, pHi 7.3 and 6.8; points measured, curves calculated by the reaction scheme in Fig. 1 D and Eqs. 5–18 with parameters listed in Table 1. (B) Sensitivity of steady-state photocurrent (100% light) to transmembrane voltage, E, and to external [H+]o, pHo between 4 and 10; points measured, curves calculated by the reaction scheme in Fig. 1 D and Eqs. 5–18 with parameters listed in Table 1. Currents I are expressed as elementary charges e per second through one rhodopsin molecule. (A) pHo = 7.3, (B) pHi = 7.3.

RESULTS

Seven independent parameters

Fig. 2 shows a typical example of the time course of photocurrents upon a rectangular light pulse and the measured parameters which can be extracted from such records. In principle, the time course provides five independent observable parameters: the three amplitudes a, b, and c and the two time constants τ1 and τ3, respectively, resulting in four parameters when the amplitudes are normalized. The initial currents (a) and the amplitude (c) are determined by extrapolating the following current relaxations to time zero. Therefore, the temporal changes upon the very beginning (τ0, not drawn) and end of the light pulse (τ2, not drawn) are not considered here because they are faster than the apparatus could resolve. Corresponding records with different light-intensities and holding voltages, as well as changes of external and internal pH, provide sufficient data to determine the seven system parameters.

Light titration

The relationships between light intensity and the amplitudes a and b (Fig. 2) of the photocurrents have been described in detail by Tsunoda et al. (3). Fig. 3 shows a typical set of such records. The theoretical records calculated by the model with the parameters in Table 1 are illustrated as black curves in Fig. 3 superimposed to the experimental data in gray. This figure shows that the basic observations are reproduced by the calculations, especially that the light-sensitivity of a is steeper than that of b, which causes the initial peak of the photocurrents to be more pronounced at increasing intensities. As can been seen from Fig. 3, the time constant τ1 is underestimated by our model fits. We ascribe these differences to an insufficient temporal resolution of the recording apparatus: Faster τ1-constants would improve the fit quality but would result in initial peaks much too high to be resolved by the apparatus.

Voltage sensitivity

Measurements and fits of the time course of photocurrents at different holding voltages are shown in Fig. 4. Interestingly, the ratio a/b (i.e., the ratio between the initial amplitude a and the steady-state amplitude, b; see Fig. 2) increases with the absolute level of b. This feature is reproduced by the model, although not as pronounced as in the experimental records. The voltage-dependence of the steady-state currents, i.e., steady-state I(E) curves are represented in more detail by Fig. 5, together with the impact of external and internal pH.

At a first glance, the sections of I(E) curves in Fig. 5 may appear quite linear. However, the irreversibility of reaction 6 renders negative photocurrents impossible. They rather approach zero at very negative E. As for the positive voltage range, the experimental data show only a weak tendency for saturation. Also, in this model, currents are not limited for large positive voltages; instead, they approach an asymptote of a finite slope of kDdD ≈ kAdA, where kD and kA rise proportional with u (Eq. 14), PD,A → 1, and dA, dD approach finite values.

pH sensitivity

Fig. 5, A and B, show the sensitivities of the steady-state currents (b) to clamp-voltages and to the concentrations of the substrate at both sides of the membrane (cytoplasmic [H+]i, pHi) and to the external [H+]o, (pHo)). Since the internal volume of the oocyte is not freely accessible, the changes in pHi cover only half a pH unit (Fig. 5 A). Nevertheless, the effect of pHi is strong, as expected for substrate-dependence. In more detail, the fits of the model to the data show a good coincidence and result in a pKi of 7.1 (Table 1, Fig. 5 A). This means that under high light conditions, the supply of Hi controls the pump current. In contrast, the sensitivity of the steady-state current-voltage relationship to the external proton concentration, [H+]o, is weak (Fig. 5 B). This is expected for an enzyme operating far from equilibrium. According to the model, the increased pumping rates observed at alkaline pHo is due to the proton release complex (C) and the protonation state of the participating amino-acid side chains. Fig. 5 B shows current changes by only a few %, per pH unit between pHo 4 and pHo 9, which is readily fitted by a pKo = 3.6 for the equilibration of the proton release complex (C). However, the observed increase of the current at pHo 10 cannot be explained by an acceptor with pKo1 3.6. The fair coincidence of fit and data at pHo 10 in Fig. 5 B could only be accomplished by the assumption of another amino acid of the proton release complex that causes equilibration with the external medium with pKo2 ≈ 10. Arg86 in AR is a likely candidate corresponding to Arg82 in BR. The curvature of the fitted curve of the model to the pHo 10 in Fig. 5 B is not strong enough to match the experimental data perfectly. It should be noted at this point that the current-voltage curve of BR does not show such a pronounced curvature (11) and that the entire proton release complex is represented here by two amino acids only.

Voltage profile

The three H+ flux components (JD = JDH→SH, Eq. 9; Js = JSH→AH, Eq. 10; and JA = JAH→CH, Eq. 11) as they result from this analysis, are plotted separately in Fig. 6 B. The serial arrangement of the fluxes (see Fig. 6) lead to the same steady-state value for each flux, whereas characteristic differences in the temporal behavior are assessed. Fig. 6 C shows steady-state values of the electric distances dD ≈ 0.27, dS ≈ 0.38, and dA ≈ 0.11, which were determined from Eqs. 13, 14, and 16–19, iteratively, as described above, whereas the value of dHi defines the voltage- and pHi sensitivity of reaction 2. During illumination the value dHi = 0.24 follows from  We use the same value as an approximation for the dark reaction. The relationship between these steady-state values of di might also be extracted from the current relaxation after light-off (e.g., Figs. 2 and 3) where the amplitude (b–c) of the immediate decay from b to c reflects the fast kinetics of the light-sensitive component JS (Fig. 6 B), and the amplitude c of the slow component is assigned to the slow kinetics of the components JD and JA. Neglecting current-contributions of the fast equilibrium (2) we can estimate from the experimental data b/c = Ilight/Ilight off ≈ 1/(dD + dA) ≈ 2.6.

We use the same value as an approximation for the dark reaction. The relationship between these steady-state values of di might also be extracted from the current relaxation after light-off (e.g., Figs. 2 and 3) where the amplitude (b–c) of the immediate decay from b to c reflects the fast kinetics of the light-sensitive component JS (Fig. 6 B), and the amplitude c of the slow component is assigned to the slow kinetics of the components JD and JA. Neglecting current-contributions of the fast equilibrium (2) we can estimate from the experimental data b/c = Ilight/Ilight off ≈ 1/(dD + dA) ≈ 2.6.

FIGURE 6.

Analytical synopsis of light-induced kinetics in H+ pumping rhodopsins. (A) Reaction scheme from Fig. 1 D with an illustration of changes in voltage profile u due to changes of electric distances d along the H+ pathway through rhodopsin under light and dark conditions. (B) Time course of the three flux components: JD, JS, and JA upon illumination of rhodopsins with 500 ms pulses of 100% light, at pHi = 7.3, pHo = 7.3, and E = 100 mV, calculated by model with parameters listed in Table 1. (C) Time course of the electrical distances dD, dS, and dA under conditions as for panel B.

The implications of the novel approach of a variable voltage profile are illustrated schematically by the lower part of Fig. 6 A. This scheme shows that during darkness there is no voltage drop across the stretches of H+ diffusion because of dD, dA = 0. Upon illumination, the voltage sensitivity coefficients dD and dA for kD and kA in Eq. 14 become >0 because of the decrease of dS from its maximum value in darkness. Fig. 6 C shows a typical example of the time course of these changes upon a rectangular pulse of bright light. It should be noted that the fits presented here infer explicit changes of di as functions of voltage, pHi, pHo, light intensity, and time.

DISCUSSION

We do not focus on the experimental data here because they have been discussed before (3). We rather point out some implications of the model for the understanding of the pump mechanism of H+ pumping rhodopsins.

The main accomplishment of this study is the description of the available electrokinetic data on H+ pumping rhodopsin at different light, pH, and voltage conditions by an enzyme kinetic reaction scheme which is in line with our spectroscopic and structural knowledge of these membrane proteins. It is clear that the description is not perfect, and does permit future refinements by appropriate extensions. However, the small number of only seven independent parameters for this description of all the data renders the numerical solution unambiguous—within the statistical limits of the experimental data, of course—which is an important benefit.

This design of the model is not the result of a straightforward strategy but the outcome of a long series of ad hoc attempts to find a powerful and satisfying reaction system.

Linear or exponential voltage-sensitivity

The impact of water networks in proton pumping is widely recognized (45) and discussed under various aspects:

Water networks can form spontaneously in cavities (46). It can be assumed that in these networks, transport can take place with hardly any barriers by a Grotthus-like mechanism (47).

The transfer of a proton between donor and acceptor, located as far as 6–7 A apart, necessitates the participation of water molecules in the process (48).

After photoabsorption, energy is partially stored in the form of the weakened hydrogen bonds (49).

It may be asked why the degenerated, linear version Eq. 14 is used to describe the voltage-sensitivity of kD and kA, because the nondegenerated, exponential form Eq. 13 can be expected to work equally well. The answer is the following:

First, the mechanism of electrodiffusion through aquatic pores can be assumed to follow the familiar, linear form of the Nernst-Plank equation.

Second, an alternative treatment by Eq. 13 summarizing several small barriers into one, would result in underestimates of the apparent di, which would result in the conceptual impossibility of

This can be demonstrated by the following example: For one symmetric Eyring barrier of the electrical width 1 between the two bases A and C, the rate constants kAC and kCA for the forward and back reactions will display the voltage sensitivities

This can be demonstrated by the following example: For one symmetric Eyring barrier of the electrical width 1 between the two bases A and C, the rate constants kAC and kCA for the forward and back reactions will display the voltage sensitivities  and

and  In case of an intermediate base B in the electrical middle, the gross reactions are kAC′ = kABC = kABkBC/(kBA + kBC) and kCA′ = kCBA = kCBkBA/(kBA + kBC), and the two barriers over the electrical width of 1/2 each will yield the overall voltage-sensitivity

In case of an intermediate base B in the electrical middle, the gross reactions are kAC′ = kABC = kABkBC/(kBA + kBC) and kCA′ = kCBA = kCBkBA/(kBA + kBC), and the two barriers over the electrical width of 1/2 each will yield the overall voltage-sensitivity  =

=  +

+  and the corresponding expression for kCA′. Shortening these expressions by exp(u/4) and ignoring exp(– u/4) for larger values of u, yields the smaller voltage-sensitivities

and the corresponding expression for kCA′. Shortening these expressions by exp(u/4) and ignoring exp(– u/4) for larger values of u, yields the smaller voltage-sensitivities  =

=  and

and  =

=  with

with  respectively. (In other words, the more barriers over a certain distance, the weaker the voltage-sensitivity of the gross reaction. The extreme case is an Ohmic-linear behavior of hopping electrons over many minute barriers in metallic conductors.)

respectively. (In other words, the more barriers over a certain distance, the weaker the voltage-sensitivity of the gross reaction. The extreme case is an Ohmic-linear behavior of hopping electrons over many minute barriers in metallic conductors.)Third, we employ Eq. 13 instead of Eq. 14 for kD and kA. Correspondingly, fits using Eq. 13 instead of Eq. 14 for the voltage-sensitivity of kD and kA, resulted in a >50% increase of the mean error. Whether the intrinsically linear slope of the I(E) curves for large positive voltages is correct or not (e.g., saturating, and thus calling for a modification of the model), might be answered by future studies. In particular, the enormous impact of the apparent charge of the empty binding site(s) within an ion transporter (50), needs to be explored here. This model, at least, satisfies the available data.

pK changes

Light-induced pK changes of the H+ binding sites in rhodopsins are well known (32,35,36). In our model, this is evident for the Schiff base, S, due to  × light in the dissociation rate constant kS. Since the light-induced increase of kS will cause concomitant changes in the voltage profile (Fig. 6 A), kD and kA will decrease due to Eq. 14 under physiological conditions of a negative voltage inside. This mechanism is visualized in Fig. 6 A by a change of the slopes of the electric field for the rate constants kA and kD for H+ electrodiffusion, from left to right and from neutral to uphill, which will cause an apparent decrease of pKD and pKA and an increase of pKC. The situation of kS is basically equivalent but more complicated due to its light-sensitivity. This view does not exclude, of course, that light and voltage may change pK values in rhodopsin by steric mechanisms as well. Nevertheless the kinetic mechanism proposed here is a compelling consequence of the model. It is expected that these kinetic pK changes differ between most spectroscopic conditions (u = 0) and physiological conditions (u < 0).

× light in the dissociation rate constant kS. Since the light-induced increase of kS will cause concomitant changes in the voltage profile (Fig. 6 A), kD and kA will decrease due to Eq. 14 under physiological conditions of a negative voltage inside. This mechanism is visualized in Fig. 6 A by a change of the slopes of the electric field for the rate constants kA and kD for H+ electrodiffusion, from left to right and from neutral to uphill, which will cause an apparent decrease of pKD and pKA and an increase of pKC. The situation of kS is basically equivalent but more complicated due to its light-sensitivity. This view does not exclude, of course, that light and voltage may change pK values in rhodopsin by steric mechanisms as well. Nevertheless the kinetic mechanism proposed here is a compelling consequence of the model. It is expected that these kinetic pK changes differ between most spectroscopic conditions (u = 0) and physiological conditions (u < 0).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tsunoda for providing files of original experimental data.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to P.H).

Editor: Francisco Bezanilla.

References

- 1.Lanyi, J. K. 2006. Proton transfers in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1757:1012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Béjà, O., L. Aravind, E. V. Koonin, M. T. Suzuki, A. Hadd, L. P. Nguyen, S. B. Jovanovich, C. M. Gates, R. A. Feldman, J. L. Spudich, E. N. Spudich, and E. F. DeLong. 2000. Bacterial rhodopsin: evidence for a new type of phototrophy in the sea. Science. 289:1902–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsunoda, S. P., D. Ewers, S. Gazzarrini, A. Moroni, D. Gradmann, and P. Hegemann. 2006. H+-pumping rhodopsin from the marine alga Acetabularia. Biophys. J. 91:1471–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waschuk, S. A., A. G. Bezerra, L. Shi, and L. S. Brown. 2005. Leptosphaeria rhodopsin: bacteriorhodopsin-like proton pump from a eukaryote. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:6879–6883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dancsházy, Z., and B. Karvaly. 1976. Incorporation of bacteriorhodopsin into a bilayer lipid membrane; a photoelectric-spectroscopic study. FEBS Lett. 72:136–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrmann, T. R., and G. W. Rayfield. 1976. A measurement of the proton pump current generated by bacteriorhodopsin in black lipid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 443:623–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bamberg, E., N. A. Dencher, A. Fahr, and M. P. Heyn. 1981. Transmembranous incorporation of photoelectrically active bacteriorhodopsin in planar lipid bilayers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 78:7502–7506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Läuger, P., R. Benz, G. Stark, E. Bamberg, P. C. Jordan, A. Fahr, and W. Brock. 1981. Relaxation studies of ion transport systems in lipid bilayer membranes. Q. Rev. Biophys. 14:513–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heyse, S., O. P. Ernst, Z. Dienes, K. P. Hofmann, and H. Vogel. 1998. Incorporation of rhodopsin in laterally structured supported membranes: observation of transducin activation with spatially and time-resolved surface plasmon resonance. Biochemistry. 37:507–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagel, G., B. Möckel, G. Büldt, and E. Bamberg. 1995. Functional expression of bacteriorhodopsin in oocytes allows direct measurement of voltage dependence of light induced H+ pumping. FEBS Lett. 377:263–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geibel, S., T. Friedrich, P. Ormos, P. G. Wood, G. Nagel, and E. Bamberg. 2001. The voltage-dependent proton pumping in bacteriorhodopsin is characterized by optoelectric behavior. Biophys. J. 81:2059–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grossfield, A., S. E. Feller, and M. C. Pitman. 2007. Convergence of molecular dynamics simulations of membrane proteins. Proteins. 67:31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levitt, D. G. 1999. Modeling of ion channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 113:789–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moy, G., B. Corry, S. Kuyucak, and S. H. Chung. 2000. Tests of continuum theories as models of ion channels. I. Poisson-Boltzmann theory versus Brownian dynamics. Biophys. J. 78:2349–2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corry, B., S. Kuyucak, and S. H. Chung. 2000. Tests of continuum theories as models of ion channels. II. Poisson-Nernst-Planck theory versus Brownian dynamics. Biophys. J. 78:2364–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuss, Z., B. Nadler, and R. S. Eisenberg. 2001. Derivation of Poisson and Nernst-Planck equations in a bath and channel from a molecular model. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 64:036116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corry, B., S. Kuyucak, and S.-H. Chung. 2003. Dielectric self-energy in Poisson-Boltzmann and Poisson-Nernst-Planck models of ion channels. Biophys. J. 84:3594–3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadler, B., U. Hollerbach, and R. S. Eisenberg. 2003. Dielectric boundary force and its crucial role in gramicidin. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 68:021905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang, J., A. Kamenev, and B. I. Shklovskii. 2005. Conductance of ion channels and nanopores with charged walls: a toy model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95:148101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherstvy, A. G. 2006. Electrostatic screening and energy barriers of ions in low-dielectric membranes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 110:14503–14506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoyles, M., V. Krishnamurthy, M. Siksik, and S.-H. Chung. 2008. Brownian dynamics theory for predicting internal and external blockages of tetraethylammonium in the KcsA potassium channel. Biophys. J. 94:366–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell, P. 1961. Coupling of phosphorylation to electron and hydrogen transfer by a chemi-osmotic type of mechanism. Nature. 191:144–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulkidjanian, A. Y. 2006. Proton in the well and through the desolvation barrier. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1757:415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagle, J. F., and H. J. Morowitz. 1978. Molecular mechanisms for proton transport in membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 75:298–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jogini, V., and B. Roux. 2007. Dynamics of the Kv1.2 voltage-gated K+ channel in a membrane environment. Biophys. J. 93:3070–3082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bezanilla, F. 2000. The voltage sensor in voltage-dependent ion channels. Physiol. Rev. 80:555–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bezanilla, F. 2005. The voltage-sensor structure in a voltage-gated channel. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30:166–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starace, D. M., and F. Bezanilla. 2004. A proton pore in a potassium channel voltage sensor reveals a focused electric field. Nature. 427:548–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abramson, J., I. Smirnova, V. Kasho, G. Verner, H. R. Kaback, and S. Iwata. 2003. Structure and mechanism of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Science. 301:610–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arkin, I. T., H. Xu, M. Ø. Jensen, E. Arbely, E. R. Bennett, K. J. Bowers, E. Chow, R. O. Dror, M. P. Eastwood, R. Flitman-Tene, B. A. Gregersen, J. L. Klepeis, I. Kolossváry, Y. Shan, and D. E. Shaw. 2007. Mechanism of Na+/H+ antiporting. Science. 317:799–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferreira, A. M., and D. Bashford. 2006. Model for proton transport coupled to protein conformational change: application to proton pumping in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128:16778–16790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spassov, V., and D. Bashford. 1998. Electrostatic coupling to pH-titrating sites as a source of cooperativity in protein-ligand binding. Protein Sci. 7:2012–2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luecke, H., B. Schobert, H. T. Richter, J. P. Cartailler, and J. K. Lanyi. 1999. Structural changes in bacteriorhodopsin during ion transport at 2 Ångstrom resolution. Science. 286:255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller, C. 1999. Ionic hopping defended. J. Gen. Physiol. 113:783–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spassov, V. Z., H. Luecke, K. Gerwert, and D. Bashford. 2001. pKa Calculations suggest storage of an excess proton in a hydrogen-bonded water network in bacteriorhodopsin. J. Mol. Biol. 312:203–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edman, K., A. Royant, G. Larsson, F. Jacobson, T. Taylor, D. van der Spoel, E. M. Landau, E. Pebay-Peyroula, and R. Neutze. 2004. Deformation of helix C in the low temperature L-intermediate of bacteriorhodopsin. J. Biol. Chem. 279:2147–2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balashov, S. P., M. Lu, E. S. Imasheva, R. Govindjee, T. G. Ebrey, B. Othersen, Y. Chen, R. K. Crouch, and D. R. Menick. 1999. The proton release group of bacteriorhodopsin controls the rate of the final step of its photocycle at low pH. Biochemistry. 38:2026–2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balashov, S. P. 2000. Protonation reactions and their coupling in bacteriorhodopsin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1460:75–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luecke, H., B. Schobert, H. T. Richter, J. P. Cartailler, and J. K. Lanyi. 1999. Structure of bacteriorhodopsin at 1.55 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 291:899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bondar, A.-N., J. C. Smith, and S. Fischer. 2006. Structural and energetic determinants of primary proton transfer in bacteriorhodopsin. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 5:547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kandt, C., J. Schlitter, and K. Gerwert. 2004. Dynamics of water molecules in the bacteriorhodopsin trimer in explicit lipid/water environment. Biophys. J. 86:705–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bard, A. J., and L. R. Faulkner. 2001. Electrochemical Methods, Fundamentals and Applications, 2nd Ed. John Wiley & Sons, New York, Chichester, Weinheim, Brisbane, Singapore, Toronto.

- 43.Nonner, W., A. Peyser, D. Gillespie, and B. Eisenberg. 2004. Relating microscopic charge movement to macroscopic currents: the Ramo-Shockley theorem applied to ion channels. Biophys. J. 87:3716–3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hookes, R., and T. Jeeves. 1961. Direct search solution of numerical and statistical problems. J. ACM. 8:212–229. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buch-Pedersen, M., B. Pedersen, B. Veierskov, P. Nissen, and M. Palmgren. 2008. Protons and how they are transported by proton pumps. Pflugers Arch. Http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00424–008–0503–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Grudinin, S., G. Büldt, V. Gordeliy, and A. Baumgaertner. 2005. Water molecules and hydrogen-bonded networks in bacteriorhodopsin-molecular dynamics simulations of the ground state and the M-intermediate. Biophys. J. 88:3252–3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pomès, R., and B. Roux. 1998. Free energy profiles for H+ conduction along hydrogen-bonded chains of water molecules. Biophys. J. 75:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedman, R., S. Fischer, E. Nachliel, S. Scheiner, and M. Gutman. 2007. Minimum energy pathways for proton transfer between adjacent sites exposed to water. J. Phys. Chem. B. 111:6059–6070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayashi, S., E. Tajkhorshid, H. Kandori, and K. Schulten. 2004. Role of hydrogen-bond network in energy storage of bacteriorhodopsin's light-driven proton pump revealed by ab initio normal-mode analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:10516–10517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gradmann, D., and C. M. Boyd. 2005. Apparent charge of binding site in ion-translocating enzymes: kinetic impact. Eur. Biophys. J. 34:353–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]