Abstract

Cancer stem cells, initiating and sustaining the tumor process, have been isolated in human and murine breast cancer using different cell markers. In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the presence and characteristics of stem/tumor-initiating cells in the model of the mouse mammary neoplasia driven by the activated form of rat Her-2/neu oncogene (BALB-neuT mice). For this purpose, we generated tumor spheres from primary spontaneous BALB-neuT tumors. Tumor sphere cultures were characterized for clonogenicity, self-renewal, and ability to differentiate in epithelial/myoepithelial cells of the mammary gland expressing basal and luminal cytokeratins and alpha-smooth muscle actin. In addition, tumor spheres were more resistant to doxorubicin compared with parental tumor cells. In the attempt to identify a selected marker for the sphere-generating cells, we found that Sca-1+ cells, present in tumors or enriched in mammospheres, and not CD24+ or CD29+ cells, were responsible for the sphere generation in vitro. Moreover, cells from the tumor spheres showed an increased tumor-generating ability in respect to the epithelial tumor cells. Sca-1+ sorted cells or clonal mammospheres derived from a Sca-1+ cell showed a superimposable tumor-initiating ability. The data of the present study indicate that a Sca-1+ population derived from mammary BALB-neuT tumors is responsible for sphere generation in culture and for initiating tumors in vivo.

Introduction

Growing evidences support the hypothesis that the tumorigenic process is sustained by a small population of cells, named tumor-initiating cells or tumor stem cells [1,2]. Tumor-initiating cells are characterized by their ability to form new serially transplantable tumors in mice and to display stem/progenitor cell properties such as competence for self-renewal and capacity to reestablish tumor heterogeneity [3,4]. Tumor stem cells have been identified in several human solid tumors and isolated by the selection for specific different markers [5–11]. In human breast carcinoma, the tumor-initiating cells have been identified by Al Hajj et al. [12] as a rare population of CD44+/CD24-/low/epithelial-specific antigen+ cells. Furthermore, tumor-initiating cells were also isolated for the ability to grow as nonadherent spheres. This property was first described for neuronal progenitors [13] and then extended to progenitors of the mammary gland [14], to human breast cell lines [15], and to human and murine breast carcinomas [16–18]. In this condition of culture, tumor-initiating cells can be expanded and maintained in an undifferentiated state [16].

In mouse mammary glands, transgenic activation of different oncogenic pathways generates tumors with particular histopathologic features, resembling the human specific types of breast carcinomas [19]. In particular, the transgenic activation of Wnt induces tumors of epithelial and myoepithelial origin, suggesting that tumors may arise from multilineage progenitor cells. In contrast, the activation of Her-2/neu oncogene (neu) generates tumors with cells more strictly committed to the luminal fate [20,21], suggesting the involvement of luminalrestricted progenitors [22]. The presence and characteristics of stem/tumor-initiating cells in the model of the mouse mammary neoplasia driven by the activated transforming form of rat neu oncogene (BALB-neuT mice) are still unknown.

This model is characterized by the overexpression of the activated rat neu oncogene under the control of the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter (MMTV) [23]. The transgene encodes a 185-kDa transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor, which is prevalently expressed in mammary glands of these mice. At 3 weeks of age, female BALB-neuT mice start a process of rapid development of tumors involving all the mammary glands.

Tumor progression in BALB-neuT mice is closely similar to that of human carcinoma, progressing from atypical hyperplasia to invasive tumor with short latency [24].Moreover, in human breast carcinoma, it has been recently described that Her-2 overexpression increased the number of stem/progenitor cells [25]. It is therefore of interest to isolate the stem cell population in a model of Her-2 activation and to identify a marker for their selection. In the present study, we aimed to evaluate whether there is a population of stem/tumor-initiating cells in the BALB-neuT tumor model. For this purpose, we generated tumor spheres from primary spontaneous tumors. Tumor spheres cultures were characterized for the self-renewal, differentiative ability and for their tumorigenic potential. In addition, we evaluated the chemoresistance of the tumor sphere to doxorubicin compared with that of parental tumor cells. Finally, we investigated whether tumor sphere-generating cells expressed selective stem cell markers that allow the identification of this population. In particular, we evaluated whether cells expressing Sca-1 were enriched in tumor spheres and were responsible for the sphere generation in vitro and for initiating tumors in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and In Vitro Expansion of Tumor Sphere-Forming Cells from Mammary Tumor Specimens

Primary mammary tumor specimens were obtained from spontaneous carcinomas developed in BALB-neuT female mice carrying the activated form of rat neu oncogene [23,24]. The histologic assessment showed a human-like lobular carcinoma of alveolar type. Tumor specimens (each time 3–6 spontaneous tumors from the same mouse; n = 15) were finely minced with scissors and then digested by incubation for 30 minutes at 37°C in DMEM containing collagenase II (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO). After washing in medium plus 10% FCS (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), the cell suspension was forced through a 40-µm pore filter (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) to separate the cell components from stroma and aggregates. Single cells were plated at 1000 cells/ml in serum-free DMEM-F12 (Cambrex BioScience, Venviers, Belgium), supplemented with 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF), 5 µg/ml insulin, and 0.4% bovine serum albumin (all from Sigma), as described [16]. Nonadherent spherical clusters of cells, named tumor spheres, appeared at day 7. At day 10, tumor spheres were collected on the bottom of a conical tube by spontaneous precipitation (10 minutes at room temperature) to remove nonliving cells. After 3 to 5 days, tumor spheres were collected and disaggregated through enzymatic and mechanical dissociation using trypsin and pipetting, respectively. Recovered cells were expanded at 1000 cells/ml in the serum-free medium described above, and the process was repeated every 10 to 12 days [17].

The single tumor cell suspension (80,000–100,000 cells/cm2) was also plated in RPMI (Sigma) supplemented with 10% of FCS to obtain adherent tumor epithelial cells.

Isolation of Selected Cell Populations from Spheres and Tumors

Subpopulation of cells were isolated from primary mammary tumor specimens and from tumor spheres in culture using antibodies (Abs) coupled to magnetic beads, by magnetic cell sorting using the magnetic-activated cells sorting (MACS) system (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). The cells suspension was incubated with the following Abs: anti-Sca-1 coupled to beads (Miltenyi Biotec), anti-CD24 and rat anti-CD29 (PharMingen, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). For CD24 and CD29, a second step reagent was needed: cells were stained by the addition of polyclonal goat antirat immunoglobulins conjugated to magnetic beads (Myltenyi Biotec). Cells were separated on a magnetic stainless steel wool column (Myltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Purity was assessed by cytofluorimetric analysis, and it was >95% in all preparations.Moreover, to test the importance of Sca-1 molecule in respect to CD24, by cell sorting, we fractioned primary mammary tumor cells into Sca-1+/CD24+ and Sca-1+/CD24- cells. Cells were labeled with the anti-CD24 Ab FITC Ab (PharMingen) and with anti-Sca-1 PE Ab.

Clonal Sphere Formation Assay

Primary tumor spheres were dissociated as described above, and 100 cells were plated in a 96-well culture plate to obtain a single cell per well in 150 µl of growth medium; 25 µl of medium per well was added every 5 days [17]. The number of clonal tumor spheres for each 96-well culture plate was evaluated after 14 days of culture. This procedure was repeated for secondary and tertiary clonal spheres and for Sca-1+ cells recovered from spheres or tumors.

Tumor Sphere Generation Assay

To investigate the number of single cells able to generate a new sphere, dissociated primary tumor spheres were cultured at the density of 1000 cells/ml; 4 ml/well of the cell suspension was placed in a six-well dish to obtain new spheres. The total number of tumor spheres for each well was counted after 14 days of culture. This procedure was repeated for three passages in culture (each passage, n = 10) [18,26]. The tumor sphere-generating ability was also evaluated for specific subpopulations of cells from tumors and spheres in culture, selected by immunomagnetic cell sorting as described above. The subpopulations were CD24- (n = 6), CD29- (n = 6), and Sca-1- (n = 11) positive and negative cells. We also tested the ability to generate sphere of Sca-1+/CD24+ and Sca-1+/CD24- cells (n = 3); the two populations were cultured at the density of 1000 cells/ml, and the total number of tumor spheres for each well was counted after 7 days of culture.

Immunofluorescence

Cytofluorimetric analysis was performed using the following Abs: purified rat anti-CD44, rat anti-CD24, rat anti-CD29, and FITC-conjugated anti-Sca-1 (PharMingen). Isotype-matched and PE-conjugated control rat IgGwere from Caltag Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with the appropriate Ab or with the irrelevant control in PBS containing 2% heat-inactivated human serum. Where needed a second step reagent, cells were stained by the addition of conjugated polyclonal goat antirat immunoglobulins/PE (Caltag Laboratories) and incubated for a further 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were analyzed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson). A total of 10,000 cells were analyzed in each sample.

For confocal microscopy analysis, indirect immunofluorescence was performed on tumor sphere-derived cells on cytospin preparation of a single cell suspension. Briefly, tumor spheres were dissociated using the nonenzymatic cell solution (Sigma). The cell suspension was centrifuged by cytospin on microscope slides and fixed by immersion on precooled acetone for 20 minutes at -20°C. For cells grown in adhesion (epithelial cells or spheres cultured in adhesion's condition), indirect immunofluorescence was performed on cells cultured on chamber slides (Nunc, Rochester, NY). Cells were fixed in 3.5% paraformaldehyde containing 2% sucrose and, when needed, permeabilized with Hepes-Triton X-100 0.1% for 10 minutes at 4°C[17]. Anti-cytokeratin 14 (CK14), anti-CK18, or anti-CK19 Abs (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) monoclonal Ab (Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark), and anti-Oct-4 Ab (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) were used.

Alexa Fluor 488 or Texas Red-conjugated antirabbit, antigoat, antirat, and antimouse IgG (all fromMolecular Probes, Leiden, the Netherlands) were used as secondary Abs. Confocal microscopy analysis was performed using a Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal model confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss International, Oberkochen, Germany). Hoechst 33258 dye (Sigma) was added for nuclear staining.

In Vitro Cell Differentiation

To evaluate the differentiative ability of cells growing as spheres, tumor spheres obtained from primary tumors were expanded, dissociated, and plated in the differentiative epithelial medium RPMI, in the presence of serum (10%), without the addition of growth factors. After 2 weeks of culture, we analyzed the expression of basal and luminal cytokeratins and myoepithelial markers as described above.

Drug Resistance Assay

The sensitivity of tumor spheres to doxorubicin was compared with that of tumor epithelial cells or of tumor spheres in differentiative condition. Tumor spheres, dissociated by trypsin as single cells, tumor epithelial cells, and differentiated sphere-derived cells were seeded in RPMI without serum (3000 cells per well). Each type of cell was stimulated for 72 hours with different doses of doxorubicin (250, 500, 1000 ng/ml). Apoptosis was evaluated by TUNEL assay (ApopTag Oncor, Gaithersburg, MD). For cells growing in suspension as spheres, we followed the manufacturer's instruction for cell suspension, and at the end, we centrifuged the plate at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes to promote cell adhesion.

Moreover, to determine the effect of drug stimulation on sphere generation, dissociated tumor spheres were plated at the density of 1000 cells/ml as described previously in the presence of 500 ng/ml of doxorubicin. The total number of spheres was counted after 6 days of culture.

In Vivo Tumorigenesis Assay

Tumor epithelial cells, tumor sphere-derived cells, or whole tumor spheres were implanted subcutaneously in the left and right flanks of syngeneic BALB/c female mice using increasing cell number (1, 5, and 50 spheres and 200, 1000, and 10,000 cells). Cells or spheres were diluted in 150 µl of PBS and injected at the first passage of culture. The growth of the tumor was monitored every week, by a caliper. We expressed the growth as mean of tumor diameter. After 9 to 12 weeks, mice were killed, and tumors were recovered and processed for histology or cell culture. For serial transplant experiments, tumors were digested in collagenase II, and the recovered cells were processed to culture in tumor sphere and epithelial conditions as described above. Mice were killed according to the ethics protocols.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections from paraffin-embedded blocks of tumors obtained in BALB/c mice were collected onto poly-l-lysine-coated slides and stained using the following Abs: goat anti-CK14, rabbit anti-CK18, or rabbit anti-neu (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 6% H2O2 for 8 minutes at room temperature. Primary Abs were applied to slides overnight or for 3 hours at 4°C, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-labeled antirabbit or antigoat Envision polymers (Dako) for 1 hour. The reaction product was developed using 3,3-diaminobenzidine. Omission of the primary Ab or substitution with an unrelated rabbit serum served as negative control.

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical and significant differences were determined using analysis of variance with the Newman-Keuls' or Dunnett's multicomparison tests when appropriate. Differences in tumor takes were evaluated with the χ2 contingency test. Differences in tumor's growth and latency time were determined by Student's t test. A P value of < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Tumor Sphere Generation from Mammary Tumors of BALB-neuT Mice

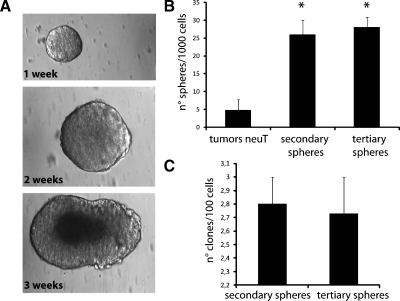

Mouse mammary tumor stem cells were obtained from mouse mammary carcinomas driven by the activated rat neu oncogene [23], exploiting their ability to grow in nonadherent conditions as spheres [16]. Tumor spheres were obtained by culturing enzymatically dissociated single-cell suspension plated at 1000 cells/ml in serum-free medium supplemented with EGF, bFGF, and insulin to promote the formation of spheres. After 2 weeks of culture, spheres resembling a golf ball-like structure were obtained, as described by Liu et al. [18]. The spheres were hollow inside in the first days; thereafter, they were filled of living cells that died if the sphere was not trypsinized at the end of the third week (Figure 1A). Primary tumor spheres, enzymatically digested after 10 to 14 days and replated as single cell suspension, generated second passage tumor spheres. This procedure was performed for more than 30 times in culture, without any difference in the sphere formation. To investigate the presence of tumor sphere-generating cells in the tumor spheres, single living cells were plated at the density of 1000 cells/ml, and the formed spheres were counted after 2 weeks. Whereas in the hole primary tumor population, the number of sphere-forming cells was 1/206 ± 12 (mean ± SD), in the disaggregated spheres in culture (secondary or tertiary), the number of sphere-forming cells was significantly increased (1/38 ± 4; mean ± SD; P < .01; Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Tumor sphere generation and self-renewal. Tumor spheres were obtained by culture of dissociated cells from mouse mammary carcinomas of BALB-neuT mice in tumor sphere medium containing EGF and bFGF. (A) Representative micrographs showing the morphology of tumor spheres within time. After 1 to 2 weeks, tumor spheres resembling a golf ball were observed; after 3 weeks, in the absence of trypsin treatment, tumor spheres showed a dark center owing to cell death. Original magnification, x200. (B) Evaluation of the number of single cells able to generate spheres. Cells were plated at the density of 1000 cells/ml. The number of sphere forming cells was higher in the disaggregated spheres in culture (secondary or tertiary) in respect to the primary tumor cell population. Data are the mean ± SD of nine different experiments. Analysis of variance with Dunnett's multicomparison test was performed on secondary and tertiary spheres versus tumor neuT: *P < .01. (C) Tumor sphere clone formation analysis in secondary and tertiary passages in culture. The number of tumor sphere clones per 100 cells was evaluated. Data are the mean ± SD of 12 different experiments.

In addition, the tumor spheres were cloned by limiting dilution of dissociated cells, by plating one single cell per well into 96-well culture plates. Clonal, nonadherent secondary tumor spheres formed, which in turn gave rise to tertiary tumor sphere clones, indicating the presence of self-renewing cells (Figure 1C).

These data indicate that a population of sphere-generating cells with self-renewal ability is present in mammary carcinomas of BALB-neuT mice, and it is enriched in the spheres.

In parallel, we isolated epithelial cells from the same BALB-neuT mammary tumors, plating the tumor single cell suspension in culture with RPMI supplemented with 10% of serum. We maintained this population for several passages in culture for comparison with cells growing as spheres.

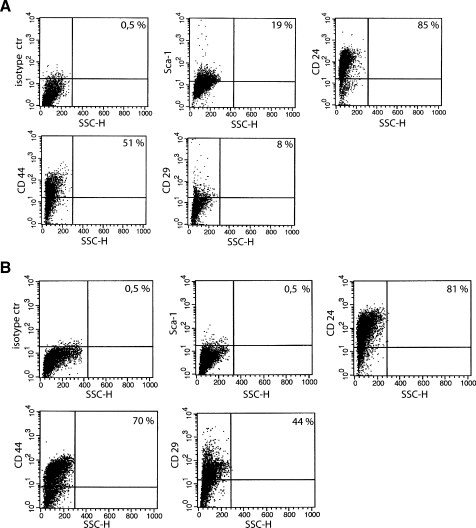

Sphere Characterization

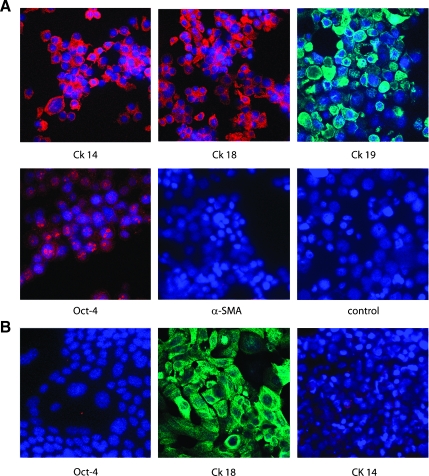

The expression of stem and differentiative markers was assessed on sphere-forming cells and compared to the entire epithelial cell population derived from the same mammary tumors. Approximately 20% of cells of the tumor spheres expressed Sca-1 (Figure 2A). Sca-1+ population was enriched in spheres compared to that of the entire cell population from BALB-neuT tumors that was around 6% to 7% (not shown). On the contrary, Sca-1 expression was undetectable in tumor epithelial cells cultured in adhesion (Figure 2B). In addition, the percentage of cells expressing CD44 and CD29 was decreased in spheres (Figure 2A) compared with epithelial cells (Figure 2B). Almost all of the cells in both spheres and adherent tumor epithelial cells were positive for CD24 (Figure 2, A and B). Cells of the tumor spheres also expressed differentiation markers of the glandular epithelium such as CK14, CK18, and CK19 (Figure 3A). In contrast, adherent tumor epithelial cells only expressed the luminal type CK18 (Figure 3B) as did the tumor of origin [19,20,27]. Moreover, some cells of tumor spheres, but no cell from tumor epithelium, showed a nuclear staining for the stem cell marker Oct-4 (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Tumor sphere characterization by cytofluorimetric analysis. Representative analysis of tumor sphere-derived cells (A) and tumor epithelial cells cultured in adhesion (B) showing the expression of Sca-1, CD24, CD44, and CD29. Sca-1+ cells were enriched in spheres, whereas the number of CD44- and CD29-expressing cells was decreased. Fifteen different experiments were performed with similar results.

Figure 3.

Expression of cytokeratins and stem cells markers on tumor spheres and tumor epithelial cells. (A) Representative micrographs showing the immunofluorescence staining by sphere-derived cells of CK14, CK18, and CK19 by confocal microscopy. Moreover, the punctuate nuclear staining of Oct-4 was observed in some cells. Negative staining was observed for α-SMA. (B) Representative micrographs showing the expression of CK18 and not CK14 or Oct-4 by adherent epithelial tumor cells by confocal microscopy. Original magnification, x650. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst dye.

We evaluated the ability of sphere-derived cells to differentiate, plating single cells in the presence of serum without growth factor supplementation, as described by Ponti et al. [16]. All plated cells grew in adherent conditions, maintained cytokeratin expression, and acquired markers associated to the myoepithelial line such as α-SMA (Figure 4). Moreover, differentiated cells lost the expression of Oct-4 (not shown). No expression of CK14 and α-SMA was observed in tumor epithelial cells in culture in the same condition. Altogether, these data suggest the presence, in the spheres, of a population with different epithelial lineage capacity able to express basal and luminal cytokeratins and myoepithelial markers.

Figure 4.

Expression of differentiation markers of the glandular epithelium by tumor spheres cultured in epithelial differentiative medium with serum. Representative micrographs showing by immunofluorescence the positivity for CK18, CK14, and CK19 (A, B, C) and the acquirement of the myoepithelial marker α-SMA (D). Original magnification, x650. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst dye.

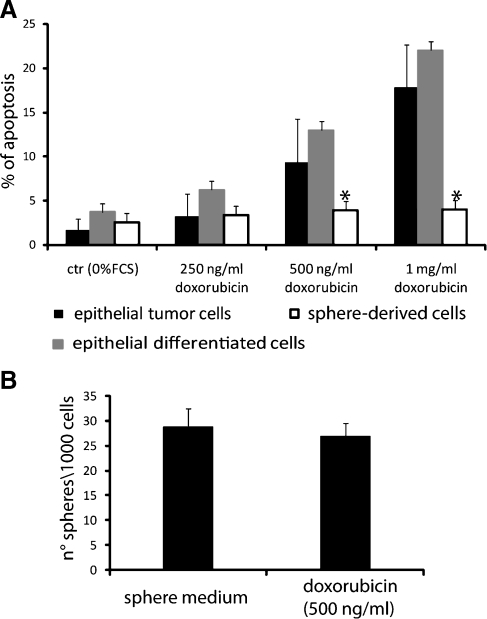

Drug Resistance of Sphere-Forming Cells

We compared the response to treatmentwith the cytotoxic drug doxorubicin in single cells from tumor spheres, in epithelial-differentiated cells cultured in adhesion, and in the primary tumor epithelial cells. Epithelial-differentiated cells cultured in adhesion and primary tumor cells underwent apoptosis after 72 hours of treatment with doxorubicin in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5A). On the contrary, cells from tumor spheres neither showed apoptosis nor significantly decreased sphere-generating ability when treated with doxorubicin (Figure 5B). These data indicate that tumor sphere-derived cells are chemoresistant to doxorubicin.

Figure 5.

Drug resistance of sphere-forming cells. (A) Sphere-derived cells (white columns), epithelial tumor cells (black columns), and spheres cultured in differentiative condition (gray columns) were treated with different dose of doxorubicin for 72 hours; apoptosis was evaluated by TUNEL assay. A significant resistance to doxorubicin was observed in sphere-derived cells. Analysis of variance with Dunnett's multicomparison test was performed among spheres-derived cells and epithelial tumor or differentiated cells: *P < .01. (B) Sphere generation from single cells in presence or not of doxorubicin (500 ng/ml). The number did not significantly decrease. Data are the mean ± SD of three different experiments performed in quadruplicate.

Sphere Generation by Sca-1-Positive Cells

To determine whether the potential of generating spheres resides in a specific subpopulation of cells, we fractioned by immunomagnetic cell sorting CD24-, CD29-, and Sca-1-positive versus-negative cells both from primary tumors and from spheres in culture. These markers were previously shown to be important for the selection of normal and cancer stem cells [18,28–32]. Every single population was plated in sphere-generating condition and compared with the negative population for the sphere-generating ability. Figure 6A shows the purity of the sorted populations. Only the Sca-1+ cell population was enriched in sphere-generating cells in respect to the total population, to the CD29- and CD24-positive and -negative cells or to the Sca-1-negative cells (Figure 6, B and C). To assess the possible role of CD24 expression in the characterization of Sca-1+ sphere-initiating cells, we further fractioned Sca-1+ cells into Sca-1+/CD24+ and Sca-1+/CD24- cells.

Figure 6.

Sphere generation by Sca-1-positive cells. CD24-, CD29-, and Sca-1-positive and -negative cells were isolated, by immunomagnetic cell sorting from primary tumors and from spheres in culture. (A) Representative cytofluorimetric analysis showing the purity of the sorted populations. (B and C) CD24-, CD29-, and Sca-1-positive and -negative cells, selected from primary tumors (B) and from spheres in culture (C) were plated at the density of 1000 cells/ml to evaluate the number of spheres obtained from single cells. Only the Sca-1+ cell population was enriched in sphere generating cells. Analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls' multicomparison test was performed among Sca-1 and unselected or selected with other markers, *P < .01; and among the positive and the negative fraction, #P < .01. Data are the mean ± SD of 10 different experiments.

No difference in sphere-generating ability was observed between the two populations (Sca-1+/CD24+: 24 ± 2; Sca-1+/CD24-: 20 ± 3, n = 3) indicating that CD24 expression was not relevant in our model. The increased ability of Sca-1+ cells to form spheres was observed when Sca-1+ cells were freshly isolated either from tumors or from cultured spheres. In the latter condition, the number of spheres generated was higher (Figure 6C), possibly owing to the enrichment of sphere-generating cells within tumor spheres.

Spheres obtained from Sca-1+ cells showed the same morphology, clonogenic ability, and marker expression of the spheres obtained from the total tumor population (not shown). Sca-1 expression in tumor spheres derived from Sca-1+ cells was still present in 20 ± 4% of cells (n = 9 experiments).

In Vivo Tumorigenesis of Spheres

To determine whether spheres differ in their tumorigenic potential from tumor epithelial cells growing as monolayer, sphere-forming cells, either as whole spheres or as single cells, and tumor-derived cells were implanted subcutaneously in the left and right flanks of syngeneic BALB/c female mice, using increasing cell number (1, 5, and 50 spheres and 200, 1000, and 10,000 sphere-derived or epithelial cells). We injected cells and spheres at the first passage of culture.

As shown in Table 1, one tumor sphere was able to generate an epithelial tumor in 6 weeks, resembling the tumor of origin, with the incidence of 50%, that increased when five spheres were injected.Moreover, cells from a disaggregated sphere (200 cells) also generated tumors with an incidence comparable to that obtained by the injection of a whole sphere. A comparable number of tumor epithelial cells did not generate tumors. Moreover, a significantly higher tumor incidence was observed using 5 tumor spheres or 1000 tumor sphere-derived cells in comparison with 1000 tumor epithelial cells (Table 1). In this condition, the tumor growthwas also significantly higher (Figure 7A). The latency time from challenge until growth of a 4-mm-diameter tumor was statistically different comparing 200 and 1000 sphere-derived cell, or the corresponding 1 and 5 spheres, with 200 and 1000 tumor epithelial cells (P < .01 and P < .05, respectively; Figure 7A).

Table 1.

Tumor-Initiating Ability of Tumor Spheres and Tumor Epithelial Cells.

| 1 Sphere/2 x 102 Cells | 5 Spheres/103 Cells | 50 Spheres/104 Cells | ||

| Primary passage | Spheres | 3/6 | 4/6 | 6/6 |

| Sphere-derived cells | 3/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | |

| Tumor epithelial cells | 0/6 | 1/6 | 6/6 | |

| Second passage | Spheres | 6/8* | 6/6 | 6/6 |

| Tumor epithelial cells | 0/6 | 3/6 | 6/6 | |

| Third passage | Spheres | 4/4* | 4/4 | ND |

| Tumor epithelial cells | 0/6 | 3/6 | ND |

Whole spheres, spheres disaggregated in single cells (sphere-derived cells), or mature tumor epithelial cells growing in adhesion were subcutaneously injected in the flank of syngeneic BALB/c female, in an increasing cell number (1, 5, and 50 spheres corresponding approximately to 200, 1000, and 10,000 cells). Tumor generation was evaluated until 3 months. For serial transplant experiments, tumor spheres and tumor epithelial cells, both obtained from primary tumors, were reinjected to evaluate second tumor generation, and the same procedure was applied for third tumor generation. ND indicates not done. Differences in tumor incidence between spheres and tumor epithelial cells were evaluated with the χ2 contingency test in every passage, *P < .01.

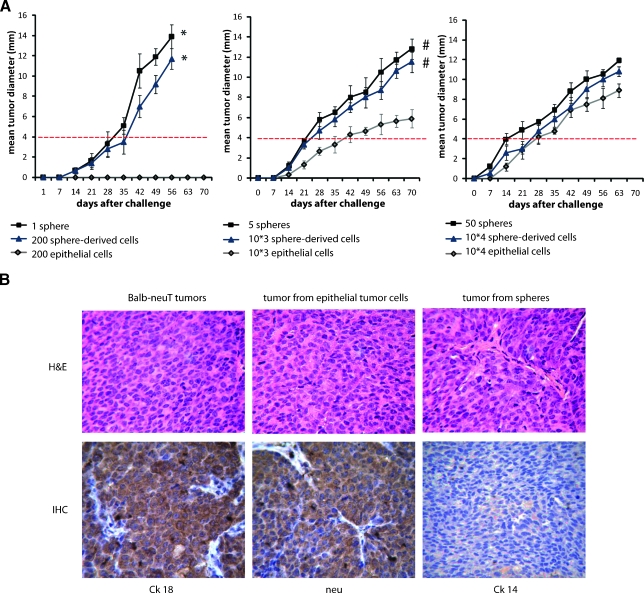

Figure 7.

Tumorigenesis assay. (A) Spheres, sphere-derived cells, and epithelial tumor cells growing as monolayer were subcutaneously injected at the first passage of culture in syngeneic BALB/c female mice, in increasing cell number (1, 5, and 50 spheres and 200, 1000, and 10,000 sphere-derived or epithelial cells). The tumor growth was monitored every week by a caliper, and the tumor diameter was measured and expressed as the tumor mean diameter. Each point represents the mean ± SD of mice developing tumors (Table 1). Student's t test was performed: *P < .01, #P < .05. The latency time from challenge until growth of 4-mm-diameter tumor (dot red line) was statistically different comparing tumors from 1 sphere or 200 sphere-derived cells with 200 tumor epithelial cells (no tumor) and comparing tumors from 5 spheres or 1000 sphere-derived cells with 1000 tumor epithelial cells (days: 24 ± 3, 26 ± 3, and 43 ± 4, respectively). Student's t test was performed: P < .05. (B) Representative micrographs showing that the tumors generated by epithelial tumor cells in culture or spheres resembled the spontaneous tumors of BALB-neuT mice. By immunohistochemistry, the sphere-derived tumors (lower panels) showed a luminal phenotype characterized by the expression of CK18 and of the neu transgene, but not of CK14. H&E indicates hematoxylin and eosin. Original magnification, x200.

To evaluate the ability to initiate tumors in serial passages, we recovered from primary tumors the cells that we cultured both as spheres and as adherent epithelial cells and we performed serial transplants (Table 1). The capacity of single spheres to generate tumors was maintained in the secondary and tertiary passages. Moreover, tumor incidence was increased within passages.

By immunohistochemistry, all the tumors resembled the tumor of origin and showed a luminal phenotype characterized by the expression of CK18 and of the neu transgene but not of CK14 (Figure 7B). These data indicate that the tumor spheres are enriched in tumor-initiating cells and that the whole sphere condition gives an advantage in respect to single cells in the tumor generation ability.

Tumorigenesis of Sca-1-Positive Cells

Injection of a single sphere derived from Sca-1+ cells displayed a tumorigenic ability comparable to that observed in a sphere from the unsorted tumor population (Sca-1+ cells: 9/12 tumors; unsorted cells: 10/12 tumors). Moreover, we generated sphere clones from Sca-1+ cells (n = 3), by plating one single Sca-1+ cell per well into 96-well culture plates in sphere medium. A single sphere from Sca-1+ clones injected subcutaneously generated tumors similar to those of origin (4/6 tumors). Finally, Sca-1+ cells were sorted from the entire fresh tumor cell population and directly injected in syngeneic mice to evaluate their tumorgenerating ability. As low as 100 Sca-1+ cells were able to generate tumors, whereas Sca-1-negative cells did not, even using 10,000 cells (Table 2).

Table 2.

Tumor-Initiating Ability of Sca1+ Cells.

| 102 Cells | 104 Cells | |

| Sca-1+ cells | 3/12 | 4/4* |

| Sca-1- cells | 0/12 | 0/6 |

Sca-1+ cells were sorted from the entire tumor cell population and directly injected in syngeneic female mice to evaluate their tumor-generating ability. A total of 100 and 10,000 Sca-1-positive and -negative cells were injected. Tumor generation was evaluated until 3 months. Differences in tumor incidence were evaluated with the χ2 contingency test, *P < .05.

Altogether, these data suggest that the Sca-1+ population is the cell population responsible for sphere generation in culture and for initiating tumors in vivo.

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that tumors driven by the activated form of the rat Her-2/neu oncogene contain a Sca-1+ population of sphere-generating cells with the ability to initiate tumors in vivo.

Tumor sphere generation is a useful tool to select a cancer stem cell population. In our experiments, tumor spheres in culture were shown to be composed of self-renewing tumor cells with the capacity to express markers of basal (CK19), luminal (CK18), and myoepithelial (CK14) differentiative lineages. In contrast, epithelial cells of the tumor only expressed the luminal type CK18 as the original tumor. These data indicate that cells originated within tumor spheres possess some potential to differentiate in vitro in the differentmammary lineages. Other cancer stem cell characteristics, also present in the tumor sphere-derived cells, were the chemoresistance and the tumor-initiating properties. Indeed, the ability to resist to drugs and to irradiation has been described in tumor stem cells [33–35] and may be of relevance for the design of tumor therapy [36,37]. Altogether, these data indicate that a population of tumor sphere-generating cells with stem cell properties is present in the model of the activated neu tumor (BALB-neuT mice). Previous studies demonstrated the presence of tumor sphere-generating cells in the model of the unactivated neu proto-oncogene mammary tumors [18]. Here, we show that the percentage of tumor sphere-generating cells was elevated in tumors driven by the activated form of neu, in line with the aggressive development of this tumor.

Different markers have been identified for the selection of mammary stem cells in the normal gland and in the different tumor models. In mice, CD24+/CD29high cells or CD24+/alpha6+ cells have been described as stem cell markers of the normal mammary gland [18,38]. CD24+/CD29high cells have also been shown expanded in preneoplastic mammary gland of MMTV-Wnt but not MMTV-neu mice. However, in mice models of MMTV-Wnt1, mammary carcinoma tumor stem cells were isolated as CD90+(Thy-1)/CD24+ cells [28]. Moreover, in the p53 null mice, mammary tumor-initiating cells were characterized by the expression of CD29/CD24 [39]. In the present study, in the attempt to identify the marker of the stem cell population present in BALB-neuT model, we comparatively evaluated the tumor sphere-generating ability ofCD29-, CD24-, and Sca-1-positive cells. The results indicate that only the Sca-1 expression identifies the sphere-generating population in this tumor model, whereas CD29- and CD24-positive cell populations did not. This finding is different from the observation by Liu et al. [18] that in tumors generated by the unactivated form of Her-2/neu, CD24 expression identifies the tumor-initiating population independently of Sca-1. In the work by Liu et al. [18], both Sca+/CD24+ and Sca-/CD24+ cells showed an increase in tumor sphere generation in vitro and in tumor-generating ability in vivo in respect to the unsorted population. In our hands, Sca1+ and not Sca1- cells were enriched of sphere-generating as well as tumor-initiating cells, independently of CD24 expression. It is possible that this differential finding will result from the different model used. Indeed, Her-2 overexpression may influence the stem cell properties of the tumor cells, as described in human cells [25]. However, as CD24 was expressed by the large majority of unsorted tumor cells (>80%), the identification of the CD24 marker as specific for tumor sphere-generating cells would be in contrast with a possible increase in sphere-generating and tumor-initiating ability of the CD24+ in respect to the unsorted population.

The observation that Sca-1+ cells immunomagnetically sorted either from cultured tumor spheres or from freshly isolated tumor cells displayed a similar increase in the generation of spheres excludes a culture-due artifact. The tumor sphere culture condition may allow the expansion of this Sca-1+ population, as the number of these cells in the spheres was significantly increased in parallel with the sphere-generating ability of the secondary spheres.

Sca-1, the first identified mouse stem cell marker, is an anchored membrane protein expressed by different progenitor populations including the mammary gland progenitors. It was primarily discovered in bone marrow stem cells and then in most tissues [40]. In the mouse mammary tumor models, an overexpression of Sca-1 in MMTV-Wnt tumors (60%) in respect to MMTV-neu tumors (6–10%) was observed [20].

In the present study, the relevance of Sca-1 expression by the tumor-initiating cells was supported by experiments of single cell generation of a tumor sphere from a Sca-1+ cell that in turn was able to generate a tumor in vivo resembling the tumor of origin. These tumors expressed CK18, but not CK14 or CK19, indicating a luminal phenotype. Indeed, the generation in BALB-neuT mice of luminal cell-restricted tumors suggests that Her-2 may expand a population of stem/progenitor cells already committed to the luminal fate [38]. The role of Her-2 in the expansion of human breast cancer stem cells has been confirmed in a recent article, showing that Her-2 overexpression increases the proportion of normal and malignant stem/progenitor cells [25].

Finally, Sca-1-positive cells freshly sorted from the tumor and injected into mice generated tumors with increased growth and incidence in respect to the tumor epithelial cells and comparable with that of the tumor sphere-generated cells, indicating their tumor-initiating ability.

In conclusion, we identified a Sca-1+ tumor stem cell population in BALB-neuT model of mammary cancer that strictly resembles the human breast carcinomas characterized by the Her-2 overexpression. A large quantity of experimental data shows the possibility of using anti-Her-2 immunotherapy to prevent the initial stages of tumor growth in the BALB-neuT model [41]. The identification of tumor stem cells in this model could allow evaluating the effect of immunotherapy also on this population, which is considered relevant for tumor maintenance.

Abbreviations

- neu

Her-2/neu oncogene

- MMTV

mammary tumor virus promoter

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- α-SMA

α-smooth muscle actin

- CK

cytokeratin

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, by the Italian Ministry of University and Research COFIN06 and ex60%, by Progetti Finalizzati Regione Piemonte and Oncoprost, and by Progetto S. Paolo Oncologia.

References

- 1.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarcke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke MF, Dick JE, Dirks PB, Eaves CJ, Jamieson CH, Jones DL, Visvader J, Weissman IL, Wahl GM. Cancer stem cells—perspectives on current status and future directions: AACR Workshop on Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9339–9344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Hajj M, Clarke MF. Self-renewal and solid tumor stem cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:7274–7282. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rafii S, Lyden D. Therapeutic stem and progenitor cell transplantation for organ vascularization and regeneration. Nat Med. 2003;9:702–712. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, Henkelman RM, Cusimano MD, Dirks PB. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins AT, Berry PA, Hyde C, Stower MJ, Maitland NJ. Prospective identification of tumorigenic prostate cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10946–10951. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prince ME, Sivanandan R, Kaczorowski A, Wolf GT, Kaplan MJ, Dalerba P, Weissman IL, Clarke MF, Ailles LE. Identification of a subpopulation of cells with cancer stem cell properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:973–978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610117104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Peschle C, De Maria R. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Brien CA, Pollet A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang D, Nguyen TK, Leishear K, Finko R, Kulp AN, Hotz S, Van Belle PA, Xu X, Elder DE, Herlyn M. A tumorigenic subpopulation with stem cell properties in melanomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9328–9337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bapat SA, Mali AM, Koppikar CB, Kurrey NK. Stem and progenitor-like cells contribute to the aggressive behavior of human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3025–3029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacques TS, Relvas JB, Nishimura S, Pytela R, Edwards GM, Streuli CH, ffrench-Constant C. Neural precursor cell chain migration and division are regulated through different beta1 integrins. Development. 1998;125:3167–3177. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.16.3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dontu G, Wicha MS. Survival of mammary stem cells in suspension culture: implications for stem cell biology and neoplasia. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2005;10:75–86. doi: 10.1007/s10911-005-2542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fillmore CM, Kuperwasser C. Human breast cancer cell lines contain stem-like cells that self-renew, give rise to phenotypically diverse progeny and survive chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/bcr1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ponti D, Costa A, Zaffarono N, Pratesi G, Petrangolini G, Coradini D, Pilotti S, Pierotti MA, Daidone MG. Isolation and in vitro propagation of tumorigenic breast cancer cells with stem/progenitor cell properties. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5506–5511. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bussolati B, Grange C, Sapino A, Camussi G. Endothelial cell differentiation of human breast tumor stem/progenitors cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00338.x. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu JC, Deng T, Lehal RS, Kim J, Zacksenhaus E. Identification of tumorsphere- and tumor-initiating cells in HER2/Neu-induced mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8671–8681. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Rosen JM. Stem/progenitor cells in mouse mammary gland development and breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2005;10:17–24. doi: 10.1007/s10911-005-2537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Welm B, Podsypanina K, Huang S, Chamorro M, Zhang X, Rowlands T, Egeblad M, Cowin P, Werb Z, et al. Evidence that transgenes encoding components of the Wnt signaling pathway preferentially induce mammary cancers from progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15853–15858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136825100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang S, Chen Y, Podsypanina K, Li Y. Comparison of expression profiles of metastatic versus primary mammary tumors in MMTV-Wnt-1 and MMTV-Neu transgenic mice. Neoplasia. 2008;10:118–124. doi: 10.1593/neo.07637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stingl J, Caldas C. Molecular heterogeneity of breast carcinomas and the cancer stem cell hypothesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:791–799. doi: 10.1038/nrc2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boggio K, Nicoletti G, Di Carlo E, Cavallo F, Landuzzi L, Melani C, Giovarelli M, Rossi I, Nanni P, De Giovanni C, et al. Interleukin 12-mediated prevention of spontaneous mammary adenocarcinomas in two lines of Her-2/neu transgenic mice. J ExpMed. 1998;188:589–596. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Carlo E, Diodoro MG, Boggio K, Modesti A, Modesti M, Nanni P, Forni G, Musiani P. Analysis of mammary carcinoma onset and progression in HER-2/neu oncogene transgenic mice reveals a lobular origin. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1261–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korkaya H, Paulson A, Iovino F, Wicha MS. HER2 regulates the mammary stem/progenitor cell population driving tumorigenesis and invasion. Oncogene. 2008 doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.207. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips TM, Kim K, Vlashi E, McBride WH, Pajonk F. Effects of recombinant erythropoietin on breast cancer-initiating cells. Neoplasia. 2007;9:1122–1129. doi: 10.1593/neo.07694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Astolfi A, Landuzzi L, Nicoletti G, De Giovanni C, Croci S, Palladini A, Ferrini S, Iezzi M, Musiani P, Cavallo F, et al. Gene expression analysis of immune-mediated arrest of tumorigenesis in a transgenic mouse model of HER-2/neu-positive basal-like mammary carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1205–1216. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62339-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho RW, Wang X, Diehn M, Shedden K, Chen GY, Sherlock G, Gurney A, Lewicki J, Clarke MF. Isolation and molecular characterization of cancer stem cells in MMTV-Wnt-1 murine breast tumors. Stem Cells. 2008;26:364–371. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Simpson KJ, Stingl J, Smyth GK, Asselin-Labat ML, Wu L, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. Generation of a functional mammary gland from a single stem cell. Nature. 2006;439:84–88. doi: 10.1038/nature04372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vassilopoulos A, Wang RH, Petrovas C, Ambrozak D, Koup R, Deng CX. Identification and characterization of cancer initiating cells from BRCA1 related mammary tumors using markers for normal mammary stem cells. Int J Biol Sci. 2008;4:133–142. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welm BE, Tepera SB, Venezia T, Graubert TA, Rosen JM, Goodell MA. Sca-1(pos) cells in the mouse mammary gland represent an enriched progenitor cell population. Dev Biol. 2002;245:42–56. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawson DA, Xin L, Lukacs RU, Cheng D, Witte ON. Isolation and functional characterization of murine prostate stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:181–186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609684104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang S, Balch C, Chan MW, Lai HC, Matei D, Schilder JM, Yan PS, Huang TH, Nephew KP. Identification and characterization of ovarian cancer-initiating cells from primary human tumors. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4311–4320. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salmaggi A, Boiardi A, Gelati M, Russo A, Calatozzolo C, Ciusani E, Sciacca FL, Ottolina A, Parati EA, La Porta C, et al. Glioblastoma-derived tumorospheres identify a population of tumor stem-like cells with angiogenic potential and enhanced multidrug resistance phenotype. Glia. 2006;54:850–860. doi: 10.1002/glia.20414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghods AJ, Irvin D, Liu G, Yuan X, Abdulkadir IR, Tunici P, Konda B, Wachsmann-Hogiu S, Black KL, Yu JS. Spheres isolated from 9L gliosarcoma rat cell line possess chemoresistant and aggressive cancer stem-like cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1645–1653. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:275–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakariassen PØ, Immervoll H, Chekenya M. Cancer stem cells as mediators of treatment resistance in brain tumors: status and controversies. Neoplasia. 2007;9:882–892. doi: 10.1593/neo.07658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stingl J, Eirew P, Ricketson I, Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Choi D, Li HI, Eaves CJ. Purification and unique properties of mammary epithelial stem cells. Nature. 2006;439:993–997. doi: 10.1038/nature04496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang M, Behbod F, Atkinson RL, Landis MD, Kittrell F, Edwards D, Medina D, Tsimelzon A, Hilsenbeck S, Green JE, et al. Identification of tumor-initiating cells in a p53-null mouse model of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4674–4682. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmes C, Stanford WL. Concise review: stem cell antigen-1: expression, function, and enigma. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1339–1347. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spadaro M, Lanzardo S, Curcio C, Forni G, Cavallo F. Immunological inhibition of carcinogenesis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:204–216. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0483-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]