Abstract

A population of the cystoid nematode Meloidoderita kirjanovae was detected parasitizing water mint (Mentha aquatica) in southern Italy. The morphological identification of this species was confirmed by molecular analysis using the internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) and 5.8S gene sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA (rDNA), which clearly separated it from the closely related species Meloidoderita polygoni. A phylogenetic analysis of M. kirjanovae with species of related genera was conducted using sequences of the D2-D3 expansion segments of the 28S nuclear ribosomal RNA gene. The resulting phylogenetic tree was congruent with trees from an extended dataset for Criconematina and Tylenchida. The basal position of the genus Meloidoderita together with Sphaeronema within the Criconematina clade in this tree may indicate their close relationships. The anatomical changes induced by M. kirjanovae population from Italy in water mint were similar to those reported for a nematode population infecting roots of M. longifolia in Israel. Nematode feeding caused the formation of a stellar syncytium that disorganized the pericycle and vascular root tissues.

Keywords: histopathology, host-parasite relationships, Mentha aquatica, molecular analysis, morphology, SEM, taxonomy, phylogeny

A population of the cystoid nematode Meloidoderita kirjanovae Poghossian, 1966 was detected parasitizing a new host, water mint (Mentha aquatica), in southern Italy. This is the first record of this plant-parasitic nematode in Italy.

The genus Meloidoderita Poghossian (1966) comprises three valid species, including Meloidoderita kirjanovae Poghossian, 1966, M. polygoni Golden & Handoo, 1984, and M. safrica Van den Berg & Spaull, 1982, which can be differentiated according to a combination of morphological and morphometrical characters (Table 1). Meloidoderita females retain the eggs inside a hypertrophied uterus that becomes a protective and persistent cystoid sac after the nematode's death.

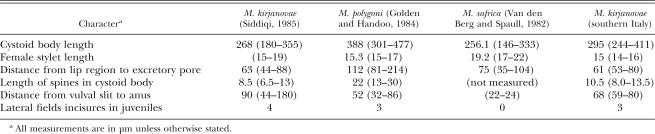

Table 1.

Morphometric characters distinguishing Meloidoderita species.

Whereas M. kirjanovae has been commonly reported parasitizing mint and grass pastures in several countries, including Armenia, Germany, Iran, Israel, Portugal (Azores), and Uzbekistan, M. polygoni and M. safrica parasitize Polygonaceae species in Beltsville, MD, and sugar cane in the Mposa area of Natal, South Africa, respectively (Van den Berg and Spaull, 1982; Sturhan, 1983; Golden and Handoo, 1984; Siddiqi, 1985). Although a complete morphological description of M. kirjanovae, based on light microscopy (LM), has been previously reported (Poghossian, 1966; Kirjanova and Poghossian, 1973; Golden and Handoo, 1984), no scanning electron microscopy (SEM) studies have been carried out on this nematode.

No molecular characterization of Meloidoderita species is available to establish a more accurate identification approach and phylogenetic relationships with related genera. According to the classification of the Criconematina proposed by Siddiqi (2000), the genus Meloidoderita is phylogenetically related to genera of the superfamily Tylenchuloidea (Skarbilovich, 1947) Raski and Siddiqui, 1975, such as Paratylenchus Micoletzky, 1922, Sphaeronema Raski and Sher, 1952, Tylenchulus Cobb, 1913, and Trophotylenchulus Raski, 1957 (Siddiqi, 2000). As a consequence of this relationship, the genus Meloidoderita is included in the family Sphaeronematidae along with the genus Sphaeronema. The other related genera mentioned above are included in the families Paratylenchidae and Tylenchulidae. Recently, Sturhan and Geraert (2005) proposed reconsidering the Criconematina and Tylenchuloidea classification because these authors observed minute phasmid-like structures in tylenchulids, Sphaeronema and Meloidoderita spp., which were absent in the species of the family Paratylenchidae. These morphological observations of important taxonomical significance were supported by molecular studies conducted by Subbotin et al. (2005) and cast doubt on the monophyly of Tylenchuloidea. The objectives of this study were to corroborate these findings and to provide information on the morphological and molecular characterization of M. kirjanovae population from Italy. Additional objectives included the phylogenetic analysis of this population with species of related genera based on sequences of the D2-D3 expansion segments of the 28S nuclear ribosomal RNA gene and a study of the anatomical alterations induced by the nematode in water mint roots.

Materials and Methods

Nematode identification and SEM studies: Specimens for morphological characterization used in this study comprised juveniles, males, cystoid bodies, and adult females collected from Laceno Lake at Avellino province (southern Italy) parasitizing water mint. The morphological and morphometric parameters of this population fitted those reported for M. kirjanovae.

For SEM studies, mature females and cystoid forms were dissected from naturally infected roots of water mint, and migratory stages (including males and second-stage juveniles) were extracted from infested soils by the centrifugal flotation method (Coolen, 1979) and by incubation of cystoid bodies and egg masses. Specimens were killed by gentle heat, fixed in a solution of 4% formaldehyde, 1% propionic acid, and processed to pure glycerin using Seinhorst's method (Seinhorst, 1966). Fixed specimens were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, critical point dried, sputter-coated with gold, and observed with a JEOL JSM-5800 microscope (Abolafia et al., 2002).

A population of M. polygoni naturally infecting roots of smartweed (Polygonum hydropiperoides Michx.) near the steam plant at Beltsville Agriculture Research Center-West, Beltsville, MD, was selected for comparative morphological and molecular analyses.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, RFLP, sequencing and phylogenetic analysis: Juveniles, cystoid bodies and females of M. kirjanovae and M. polygoni from host and localities indicated above were used for molecular analyses. Total DNA was extracted from single adult females or juveniles of M. kirjanovae and also from M. polygoni according to Subbotin et al. (2000). The detailed protocol for PCR was described by Tanha Maafi et al. (2003). The following primer pairs were used for amplification and sequencing of the D2-D3 fragment of the 28S rRNA gene and the ITS region of rRNA gene (ITS1 for M. polygoni and ITS1–5.8S-ITS2 for M. kirjanovae), respectively: forward D2A (5′-ACAAGTACCGTGAGGGAAAGTTG-3′ and reverse D3B (5′-TCGGAAGGAACCAGCTACTA-3′) (Subbotin et al., 2005); forward TW81 (5′-GTTTCCGTAGGTGAACCTGC-3′) and reverse 5.8SM5 (5′-GGCGCAATGTGCATTCGA-3′) (Zheng et al., 2000) or forward 18S (5′-TTGATTACGTCCCTGCCCTTT-3′) and reverse 26S (5′-TTTCACTCGCCGTTACTAAGG-3′) (Vrain et al., 1992). The ITS1–5.8S-ITS2 PCR products of M. kirjanovae and M. polygoni were purified with a gel extraction kit (Geneclean turbo; Q-BIOgene, Illkirch, France) and quantified using the Quant-iT DNA Assay Kit Broad Range fluorometric assay (Molecular Probes, Inc., Leiden, The Netherlands) with a Tecan Safire fluorospectrometer (Tecan Spain, Barcelona, Spain) according to manufacturer's instructions. The D2-D3 amplification products of M. kirjanovae were cloned into the pGEM-T vector and transformed into JM109 High Efficiency Cells (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). PCR products of the ITS region and several D2-D3 clones were submitted for DNA sequencing. Amplicons were sequenced in both directions with a BigDye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, Madrid, Spain) using the amplification primers listed above according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting products were purified and run on a Model 3100 DNA multicapillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems) at the University of Córdoba sequencing facilities. The sequences reported here for M. kirjanovae and M. polygoni have been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers DQ768428 (D2-D3 fragment for M. kirjanovae), DQ768427 (ITS1–5.8S-ITS2 region for M. kirjanovae), DQ768425 and DQ768426 (ITS1 region for two clones of M. polygoni).

The D2-D3 sequence of M. kirjanovae was aligned using ClustalX 1.83 (Thompson et al., 1997) with published D2-D3 sequences of 29 species of tylenchid nematodes and three species of Aphelenchida chosen as outgroup taxa (Subbotin et al., 2006). After removing ambiguously aligned regions from an alignment, we applied a Bayesian interference analysis (BI) for the data set using MrBayes 3.0 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, 2001). We used a general-time-reversible (GTR) model of nucleotide substitution and a gamma distribution (G) of among-site rate heterogeneity with six rate categories estimated as the best-fit model by ModelTest to the present data set. Bayesian analyses were initiated with random starting trees and were run with four chains for 1.0 × 106 generations. Markov chains were sampled at intervals of 100 generations. The log-likelihood values of the sample points stabilized after approximately 103 generations. After discarding burn-in samples and evaluating convergence, the remaining samples were retained for further analysis. The topologies were used to generate a 50% majority rule consensus tree, with posterior probabilities (PP) given as support for appropriate clades.

The ITS1 region sequences of M. kirjanovae and M. polygoni were aligned with ClustalX 1.83 (Thompson et al., 1997) with default options.

Histopathology: Naturally infected water mint roots segments were gently washed free of adhering soil and debris, and individual infected root portions were selected together with healthy roots. Root tissues were fixed in formaldehyde chromo-acetic solution for 48 hr, dehydrated in a tertiary butyl alcohol series (40–70–85– 90–100%), and embedded in 58°C (melting point) paraffin wax for histopathological observations. Embedded tissues were sectioned with a rotary microtome. Sections of 10 to 12 μm thickness were placed on glass slides, stained with safranin and fast-green, mounted permanently in 40% xylene solution of a polymethacrylic ester (Synocril 9122X, Cray Valley Products, NJ), examined microscopically, and photographed (Johansen, 1940).

Results

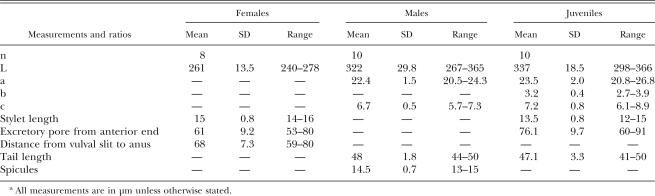

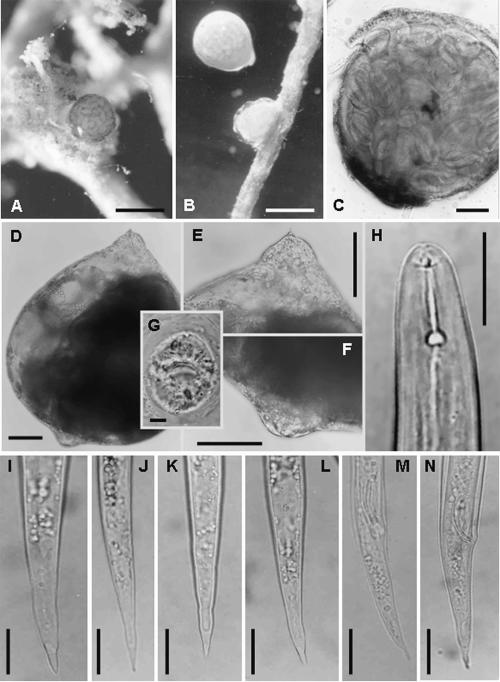

Morphological and SEM studies: Meloidoderita kirjanovae was identified by means of LM and SEM examinations. Measurements of females, cystoid bodies, males, and juveniles from glycerin mounts of the Italian population of M. kirjanovae are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Females are rather pear-shaped, have protruding terminal vulva, and have a smooth, thick cuticle (3–3.5 μm). Only the neck and anterior region of the female extend into the root, and the exposed body is surrounded by a gelatinous matrix up to two times the size of the female. The gelatinous matrix becomes filled with eggs, and, as the second-stage juveniles hatch from these eggs, a brown cystoid uterine sac filled with eggs develops within the female. The uterine sac has a thick surface with prominent spines and might occupy almost the entire female body (Figs. 1F-L;2C-F). Second- stage juveniles of the Italian population of M. kirjanovae showed a lip region lacking annuli and a lateral field marked by three lines (Figs. 1F-L;2C-F). Males were common and lacked stylet and bursa (Fig. 1M,N). These observations indicated that the ornamentation (spines) of the uterine cystoid sac and the biology of the Italian population of M. kirjanovae were similar to those reported for a population of this species from Israel (Cohn and Mordechai, 1982; Golden and Handoo, 1984). In general, morphometry of all life stages of the Italian population of M. kirjanovae was shown to be slightly shorter than that of populations from Israel and Russia in body length and distance from excretory pore to anterior end, but was quite similar in other characters such as stylet or spicules length. The body length of juveniles from M. kirjanovae from Italy and Israel is clearly shorter than that from M. polygoni (298–417 μm vs. 408–504 μm), which could be used as an additional diagnostic character to differentiate these species. However, additional measurements of a higher number of specimens and populations should be considered before a clear decision on that matter can be made.

Table 2.

Morphometrics of Meloidoderita kirjanovae parasitizing water mint (Mentha aquatica) at Laceno at Avellino province (southern Italy).

Fig. 1.

Photomicrographs of specimens of Meloidoderita kirjanovae. A-C) Cystoid bodies on mint root. D) Adult female, whole specimen. E,F) Details of anterior and posterior female body portions. G) Detail of vulval region. H) Second-stage juvenile lip region. I-K) Second- stage juvenile tail regions. L,M) Male tail region. Scale bars: A,B = 250 μm; C-F = 50 μm; G-M = 15 μm.

Fig. 2.

SEM micrographs of juveniles and cystoid bodies of Meloidoderita kirjanovae. A,B) Juveniles. C) Whole cystoid body. D) Gelatinous matrix containing eggs. E) Surface of cystoid body showing the posterior portion of a second-stage juvenile. F) Spines and surface markings of cystoid body. Scale bars: A = 5 μm; B = 10 μm; C = 200 μm; D,F = 20 μm; E = 100 μm.

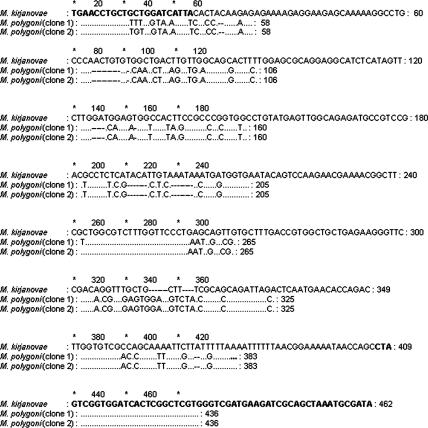

Molecular characterization and phylogenetic relationships with other nematodes: The nematode was identified by molecular diagnostics using the internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1), 5.8S gene sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA (rDNA), and sequences of the D2-D3 expansion segments of the 28S rDNA gene. Amplification of the ITS region rRNA gene of M. kirjanovae using primer combination of 18S and 28S generated a PCR product with a gel-estimated length of approximately 1,000 bp. A portion of the ITS alignment, including the 18S and 5.8S rRNA genes from M. kirjanovae and M. polygoni, is presented in Figure 3. The length of the ITS1 region of M. polygoni was shorter that those of M. kirjanovae and differs in 63 to 64 nucleotides (15%) from this species.

Fig. 3.

Partial (473 bp) ITS1-rRNA sequence alignment for two species of Meloidoderita with 18S and 5.8S rRNA gene sequences shown in bold. Identities with M. kirjanovae are indicated by a period; gaps are denoted by dashed lines.

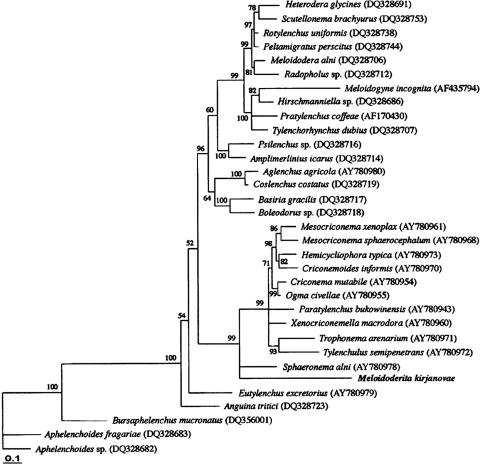

To analyze the position of the genus Meloidoderita within tylenchids and avoid influence of the possible high level of data saturation on phylogenetic reconstruction, we used a conservative approach to create a sequence data set known as a culled alignment. The culled alignment was created from an automatic alignment containing 713 bp by manually removing 147 ambiguously aligned nucleotide positions, comprising 21% of the alignment length. A Bayesian interference analysis majority consensus tree indicated the division of Tylenchida into several main clades (Fig. 4). Meloidoderita kirjanovae clustered with high PP (99%) with representatives of the suborder Criconematina and occupied a basal position in this clade together with Sphaeronema alni.

Fig. 4.

The 50% majority rule consensus tree from Bayesian analysis generated with the GTR+I+G model. Trees were obtained for a culled (566 bp) alignment of the 28S-rRNA D2-D3 expansion region from 33 taxa of the Tylenchida and Aphelenchida. Posterior probability is given as a percentage for each appropriate clade.

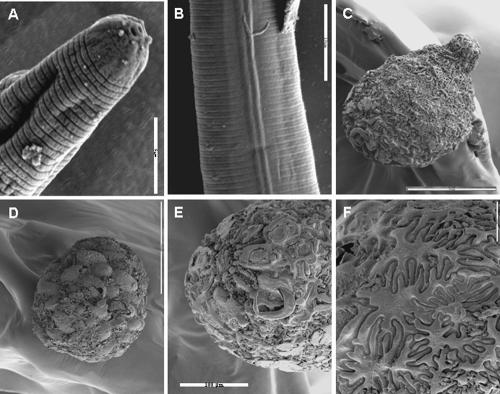

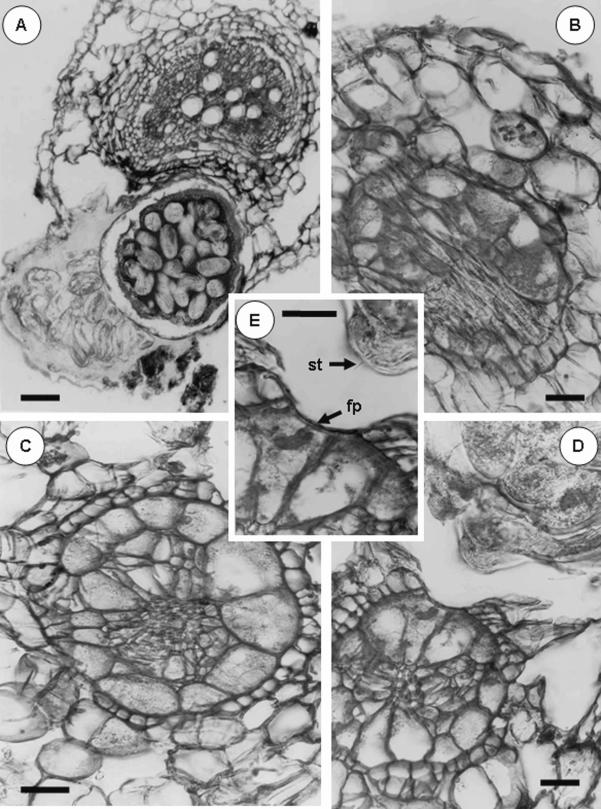

Histopathology: Severe infections of M. kirjanovae were detected on young roots of M. aquatica. Adult females of M. kirjanovae protruded from the surface of all infected root segments (Fig. 1A,B) occurring individually or in clusters, but did not cause distortion of the entire root diameter (Fig. 1B). Usually, there was a single female in each of the numerous, randomly selected infected sites that were microscopically observed (Fig. 1B), but two or three mature females occasionally were found together. Eggs were laid in a gelatinous matrix regularly protruding from the root surface (Fig. 5A), but the cystoid body was often located within the root cortex (Fig. 5A). Histological observations of Meloidoderita-infected mint roots (Fig. 5A-E) showed formation of a syncytium at the nematode feeding site. Syncytium expansion induced alterations of the endodermis, peri- cycle and vascular cylinder as well as a disorganization of the root cortex (Fig. 5A-E). Commonly, the nematode feeding sites comprised six to eight syncytial cells surrounding the nematode's lip region, but in some cases up to 12 syncytial cells which gradually decreased in size with increased distance from the nematode lip region were induced by a single female, (Fig. 5C). Syncytial cells showed the characteristic cytological features of granulated cytoplasm, thickened cell walls, and a hypertrophied nucleus and nucleolus (Fig. 5D,E). In some cases, some parenchymatic cells in the stele close to the pericycle contained dense protoplasm, but generally no change in their size was observed (Fig. 5C). These anatomical changes did not differ from those described by Cohn and Mordechai (1982) in M. longifolia roots infected by a M. kirjanovae population from Israel.

Fig. 5.

Histopathology of Meloidoderita kirjanovae in roots of Mentha aquatica. A) Transverse section of root of mint infected by M. kirjanovae showing the nematode female (N) inside the cortical parenchyma. B-E) Reactions of cortical and pericycle cells to nematode infection showing syncitial formation. E) Details of the feeding cell on which distinct feeding peg (fp) is formed, st = Stylet. Scale bars: A = 100 μm; B-E = 25 μm)

Discussion

Accurate identification of Meloidoderita spp. is a hard task because some of the differential diagnostic characters are difficult to observe in second-stage juvenile or adult stages (e.g., lateral fields). In fact, Sturhan (1983) identified second-stage juveniles and males of Meloidoderita from Iran as M. kirjanovae; but did not speciate with certainty the populations from Germany and Azores.

Based on morphometrical and morphological characteristics, the cystoid nematode population from southern Italy infecting water mint was identified as M. kirjanovae. Although we have no exact data on the possible origin of this population of M. kirjanovae in Italy, because of its finding in a naturally isolated environment, such as Laceno Lake at Avellino province (southern Italy), we hypothesized that this population is native to Italy. The morphological and morphometric parameters of M. kirjanovae populations from different geographical origins listed in the literature do not match exactly with our population. Kirjanova and Poghossian (1973) reported in their redescription that M. kirjanovae had four incisures in the lateral field of the male and juveniles, but Golden and Handoo (1984) observed only three incisures in the lateral field of specimens from Armenia and Israel. Our SEM data supported these observations confirming the presence of three incisures. Similarly, the lip region of second-stage juveniles of the Italian population of M. kirjanovae was smooth under SEM observations, while in the type population three to four annuli were reported (Kirjanova and Poghossian, 1973). The results of our examination also agree with those reported for a population of M. kirjanovae from Israel (Cohn and Mordechai, 1982). The secretion of the gelatinous matrix from the vulva in M. kirjanovae differs from that of other tylenchulids such as Tylenchulus and Trophonema which secrete the gelatinous matrix from the excretory pore. This physiological characteristic may corroborate the results of the phylogenetic analysis.

The molecular analysis based on the internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) and 5.8S gene sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA (rDNA) clearly separated M. kirjanovae from M. polygoni. This molecular approach is a very useful and reliable tool for the identification of cystoid nematodes, especially when a small number of specimens is available. The phylogenetic (BI) tree from the present analysis was congruent with trees obtained from extended dataset for Criconematina (Subbotin et al., 2005) and Tylenchida (Subbotin et al., 2006). The basal position of the genus Meloidoderita together with Sphaeronema within Criconematina clade in our tree may indicate their close relationships. The hypotheses considering Meloidoderita as member of the family Sphaeronematidae (Siddiqi, 2000) or as member of the family Meloidoderitidae as earlier proposed by Kirjanova and Poghossian (1973) require further testing and analyses using other genetic markers and more representatives of sedentary nematodes of the suborder Criconematina.

Although the general pattern of parasitism found in this study is in general agreement with that described for M. kirjanovae by Kirjanova and Poghossian (1973) and Cohn and Mordechai (1982) in Urtica dioica L. and Mentha longifolia L., respectively, parasitism of M. kirjanovae on M. aquatica did not show any swelling of the root tissue around the nematode infection point, which was reported by Cohn and Mordechai in M. longifolia roots. Andrews et al. (1981) reported a similar parasitism pattern from a population of Meloidoderita sp. from Maryland (later described as M. polygoni) on Polygonum hydropiperoides Mild. Comparison of our results on histopathology with those reported by Subbotin and Chizhov (1986) indicated that M. kirjanovae infecting mint induced formation of syncytia which comprise about 400 cells. These cells had enlarged nuclei, vacuolated cytoplasm, and a high number of organelles. Syncytia clearly differ from those induced by Heterodera spp. (absence of protuberances on cell wall) or Rotylenchulus reniformis (larger size and more intensive lysis of a cell wall).

In conclusion, the biological and morphological observations and the molecular analyses conducted in this study suggest that M. kirjanovae populations from Italy and Israel may have originated from the same source.

Footnotes

This research was partially supported by bilateral agreements between the Spanish National Research Council (C.S.I.C.) and the Italian National Research Council (C.N.R.). The authors thank A. Brandonisio and J. Martín Barbarroja for technical assistance, and the editor and anonymous reviewers for their useful and constructive suggestions for improving the manuscript. SAS acknowledges support from USDA grant 2005–00903. Mention of trade name or commercial product in this publication is solely the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

This paper was edited by Andrea Skantar

Literature Cited

- Abolafia J, Liébanas G, Peña-Santiago R. Nematodes of the order Rhabditida from Andalucia Oriental, Spain. The subgenus Pseudacrobeles Steiner, 1938, with description of a new species. Journal of Nematode Morphology and Systematics. 2002;4:137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews SW, Krusberg LR, Golden AM. The host range, life-cycle and host-parasite relationships of Meloidoderita sp. Nematologica. 1981;27:146–159. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn E, Mordechai M. Biology and host-parasite relations of a species of Meloidoderita (Nematoda: Criconematoidea) Revue de Nématologie. 1982;5:247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Coolen WA. Methods for extraction of Meloidogyne spp. and other nematodes from roots and soil. In: Lamberti F, Taylor CE, editors. Root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne species). Systematics, biology, and control. New York: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 317–329. [Google Scholar]

- Golden AM, Handoo ZA. Description of Meloidoderita polygoni n. sp. (Nematoda: Meloidoderitidae) from USA and observations on M. kirjanovae from Israel and USSR. Journal of Nematology. 1984;16:265–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MrBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirjanova ES, Poghossian EE. A redescription of Meloidoderita kirjanovae Poghossian, 1966 (Nematoda; Meloidoderitidae, fam. n) (Transl. from Russian) Parazitologiya. 1973;7:280–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen DA. Plant microtechnique. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Poghossian EE. A new genus and species of nematode of the family Heteroderidae from the Armenian SSR (Nematoda) (Transl. from Russian.) Dan Reports of the Academy of Sciences of the Armenian SSR. 1966;47:117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Seinhorst JW. Killing nematodes for taxonomic study with hot f.a. 4:1. Nematologica. 1966;12:78. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi, M.R. 1985. Meloidoderita kirjanovae. Descriptions of plant-parasitic nematodes, St Albans, UK, Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, Set 8, No. 113, pp 2.

- Siddiqi MR. Tylenchida: Parasites of plants and insects. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sturhan D. First records of the genus Meloidoderita (Nematoda; Criconematoidea) in Iran, Germany and the Azores. Nematologica. 1983;29:488–490. [Google Scholar]

- Sturhan D, Geraert E. Phasmids in Tylenchulidae (Tylenchida: Criconematoidea) Nematology. 2005;7:249–252. [Google Scholar]

- Subbotin SA, Chizhov VN. Syncytia induced in roots of mint by Meloidoderita kirjanovae Pogosyan, 1966. Byulleten’ Vsesoyuznogo Instituta Gel’ mintologii im KI Skryabina. 1986;45:52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Subbotin SA, Sturhan D, Chizhov VN, Vovlas N, Baldwin JG. Phylogenetic analysis of Tylenchida Thorne, 1949 as inferred from D2 and D3 expansion fragments of the 28S rRNA gene sequences. Nematology. 2006;8:455–474. [Google Scholar]

- Subbotin SA, Vovlas N, Crozzoli R, Sturhan D, Lamberti F, Moens M, Baldwin JG. Phylogeny of Criconematina Siddiqi, 1980 (Nematoda: Tylenchida) based on morphology and D2-D3 expansion segments of the 28S rDNA gene sequences with application of a secondary structure model. Nematology. 2005;7:927–944. [Google Scholar]

- Subbotin S, Waeyenberge AL, Moens M. Identification of cyst-forming nematodes of the genus Heterodera (Nematoda: Heteroderidae) based on the ribosomal DNA-RFLPs. Nematology. 2000;2:153–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tanha Maafi Z, Subbotin SA, Moens M. Molecular identification of cyst-forming nematodes (Heteroderidae) from Iran and a phylogeny based on ITS-rDNA sequences. Nematology. 2003;5:99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The ClustalX windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg E, Spaull VW. A new Meloidoderita species on sugar cane in South Africa (Nematoda:Meloidoderitidae) Phytophylactica. 1982;14:205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Vrain TC, Wakarchuk DA, Levesque AC, Hamilton RI. Intraspecific rDNA Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism in the Xiphinema americanum group. Fundamental and Applied Nematology. 1992;15:563–573. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Subbotin SA, Waeyenberge L, Moens M. Molecular characterisation of Chinese Heterodera glycines and H. avenae populations based on RFLPs and sequences of rDNA-ITS regions. Russian Journal of Nematology. 2000;8:109–113. [Google Scholar]